Abstract

Relatively less right parietal activity may reflect reduced arousal and signify risk for major depressive disorder (MDD). Inconsistent findings with parietal electroencephalographic (EEG) asymmetry, however, suggest issues such as anxiety comorbidity and sex differences have yet to be resolved. Resting parietal EEG asymmetry was assessed in 306 individuals (31% male) with (n = 143) and without (n = 163) a DSM-IV diagnosis of lifetime MDD and no comorbid anxiety disorders. Past MDD+ women displayed relatively less right parietal activity than current MDD+ and MDD- women, replicating prior work. Recent caffeine intake, an index of arousal, moderated the relationship between depression and EEG asymmetry for women and men. Findings suggest that sex differences and arousal should be examined in studies of depression and regional brain activity.

In recent years, researchers have examined the brain mechanisms involved in cognitive and emotional disturbances in depressed individuals to identify endophenotypes, biological markers of risk that may improve diagnosis and treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) (e.g., Hasler, Drevets, Manji, & Charney, 2004; Mayberg, 2003). Although the research spotlight often focuses on the prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices, the parietal cortex has also been implicated in depression-related attention and executive function deficits in both cognitive and emotional tasks and is thus a valuable candidate of study (Liotti & Mayberg, 2001; Mayberg, 1997). It has been argued that depression is particularly associated with impaired right parietal cortex function, reflecting reduced arousal and impaired processing of emotional stimuli (e.g., Bruder, 2003; Heller, 1993; Heller & Nitschke, 1997). This impairment is evident on neuropsychological tests of perceptual asymmetry (e.g., Heller, Etienne, & Miller, 1995; Keller et al., 2000) and in event-related potential studies of emotional perception (Deldin, Keller, Gergen, & Miller, 2000; Kayser, Bruder, Tenke, Stewart, & Quitkin, 2000), lateralized auditory processing (e.g., Bruder et al., 1995; Bruder, Wexler, Stewart, Price, & Quitkin, 1999; Bruder et al., 2002) and spatial task performance (Henriques & Davidson, 1997; Rabe, Debener, Brocke, & Beauducel, 2005), suggesting that right parietal hypoactivity in depression may manifest under many conditions, particularly for tasks that require right hemisphere processing.

Rather than simply serving as a state index of depression status, right parietal hypoactivity may instead represent an endophenotype of depression that could provide insight into mechanisms involved in risk for depression. Relatively lower right resting parietal electroencephalogram (EEG) activity (inferred by relatively greater right alpha band activity; see Allen, Coan, & Nazarian, 2004) distinguishes both symptomatic and remitted depressed individuals from never-depressed individuals (Blackhart, Minnix, & Kline, 2006; Bruder et al., 1997; Henriques & Davidson, 1990; Kentgen et al., 2000), is prominent in family members of MDD patients (Bruder et al., 2005; Bruder, Tenke, Warner, & Weissman, 2007), and is linked with other indices of depression risk such as low positive emotionality (Hayden et al., 2008; Shankman et al., 2005), suggesting that parietal EEG asymmetry may also be a psychophysiological indicator for depression risk. Consistent with this hypothesis, parietal brain asymmetry demonstrates reliable trait-like properties in clinical and non-clinical samples (e.g., Debener et al., 2000; Hagemann, Naumann, Thayer, & Bartussek, 2002; Vuga et al., 2006), and in contrast to frontal asymmetry that appears to reflect not quite 60% stable trait variance across recording sessions, parietal asymmetry has higher trait variance, with approximately 70% reflecting stable trait variance (Hagemann et al., 2002) and convergence across EEG reference montages (Hagemann, Naumann, & Thayer, 2001; Henriques & Davidson, 1990; but see Reid, Duke & Allen, 1998 and Tomarken, Dichter, Garber, & Simien, 2004).

Several resting EEG studies, however, have failed to confirm an association between right parietal hypoactivity and depression (e.g., Debener et al., 2000; Deslandes et al., 2008; Henriques & Davidson, 1991; Mathersul, Williams, Hopkinson, & Kemp, 2008; Nitschke, Heller, Palmieri, & Miller, 1999). Furthermore, within high risk samples, infants of depressed mothers have not displayed less right than left parietal activity (e.g., Dawson, Frey, Panagiotides, Osterling, & Hessl, 1997; Diego et al., 2004; Field, Fox, Pickens, & Nawrocki, 1995; Jones, Field, Fox, Lundy, & Davalos, 1997; Jones et al., 1998), and another study showed that adolescents with depressed mothers exhibited relatively greater, not less, right parietal activity than their low risk counterparts (Tomarken et al., 2004). Inconsistent results may be due to a number of factors, including small patient samples, diagnostic heterogeneity and anxiety comorbidity, depression recruitment strategies, and sex differences in depression and/or EEG asymmetry (e.g., Davidson, 1998; Heller & Nitschke, 1998). With respect to patient samples, a few studies demonstrate effects in the predicted direction but do not reach significance, likely due to the limited number of depressed patients included (e.g., Allen, Iacono, Depue, & Arbisi, 1993). Significant parietal EEG asymmetry results between pure MDD patients and controls tend to possess a medium effect size (e.g., Bruder et al., 1997; Reid et al., 1998), requiring a substantial number of subjects to detect group differences, which may explain null results for studies with small sample sizes (e.g., Henriques & Davidson, 1991). Conflicting results across studies may also be a result of heterogeneity of depressed samples, perhaps due to subtypes of depression such as seasonal affective disorder (e.g., Allen et al., 1993; Volf & Passynkova, 2002), anhedonic depression (Nitschke et al., 1999), and depression co-occurring with types of comorbid anxiety that are associated with opposing patterns of brain asymmetry than those displayed by non-anxious depressed individuals (Heller & Nitschke, 1998). For example, anxious apprehension (worry) has been linked to relatively less right hemisphere activity, and anxious arousal (somatic symptoms of anxiety) to relatively more right hemisphere activity (e.g., Heller, Nitschke, Etienne, & Miller, 1997; Nitschke et al., 1999), patterns that could potentially exaggerate or cancel out relatively lower right parietal activity in depression. Consistent with this proposition research indicates that: 1) individuals with MDD and at least one anxiety disorder display relatively more right parietal activity than MDD patients without anxiety (Bruder et al., 1997); 2) comorbid anxiety disorders in adolescents with MDD were associated with relatively greater right parietal activity (Kentgen et al., 2000); and, 3) comorbid anxious arousal and depression symptoms were linked to relatively greater right parietal activity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (Metzger et al., 2004). Differences between pure and comorbid depressed individuals, however, are not consistently found (Mathersul et al., 2008), potentially due to the type of recruitment strategy used to obtain depressed individuals (i.e., on the basis of a DSM-IV diagnoses versus questionnaires measuring symptoms of depression and anxiety). Null results are apparent in some studies using questionnaires measuring current depressive symptoms (e.g., Deslandes et al., 2008; Diego, Field, & Hernandez-Reif, 2001; Harmon-Jones et al., 2002; Nitschke et al., 1999; Reid et al., 1998; Schaffer, Davidson, & Saron, 1983), consistent with research indicating that some depression scales may also index anxiety (Nitschke, Heller, Imig, McDonald, & Miller, 2001), and may cancel out lateralization effects associated with depression. Table 1 summarizes studies examining the relationship between parietal EEG asymmetry and depression.

Table 1.

Studies of Resting Parietal EEG Asymmetry and Depression

| Citation | Sample | Age | Handedness | Reference Scheme and Parietal Sites | Primary Assessment of Depression | Parietal Results Summary | Hemisphere Analysis | Gender Difference Analysis | Comorbid Anxiety Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. (1993) | 4 women with bipolar seasonal affective disorder (SAD); 4 female control subjects | Pre-menopausal | Right | Cz; P4-P3 | DSM-III-R criteria | SAD group marginally ↓ RPA than control group | No | No | No |

| Blackhart et al. (2006) | 28 (23 female) | 18-25 | Right | LE; P4-P3 | BDI | ↑ BDI scores predicted ↓ RPA | No | Yes, no effects involving gender found | Yes; participants had no reported history of psychopathology; anxiety symptoms did not predict parietal asymmetry |

| Bruder et al. (1997) | 19 anxious-depressed (9 female); 25 non-anxious depressed (13 female); 26 control subjects (13 female) | 20-60 | 50 right and 10 left | Cz, Nose; P4-P3, P8-P7 | DSM-III-R criteria | Anxious-depressed ↑ RPA than LPA; Non-anxious-depressed ↓ RPA than LPA; controls showed parietal symmetry; non-anxious depressed ↓ RPA than anxious-depressed | Yes | No | Yes; addressed in main analysis with anxiety groups; also found no relationship between STAI and asymmetry |

| Bruder et al. (2005) | 18 offspring of 2 parents with MDD (10 female); 40 offspring of 1 parent with MDD (25 female); 29 controls with no MDD parents (18 female) | 8-50 | Right | LE; P4-P3, P8-P7 | DSM-IV criteria | Offspring of 2 parents with MDD ↓ RPA than offspring of 1 parent with MDD and controls | Yes | No | Yes; anxiety symptoms did not moderate results |

| Bruder et al. (2007) | 19 (11 female) offspring having parent and grandparent with MDD; 14 (6 female) offspring having parent or grandparent with MDD; 16 (9 female) offspring with neither parent or grandparent with MDD | Right | Offspring with 2 MDD relatives M = 15.4, SD = 4.7; offspring with 1 MDD relative M = 13.6, SD = 6.2; controls M = 10.6, SD = 4.5 | LE; P4-P3, P8-P7 | DSM-IV criteria | Offspring of 2 MDD relatives ↓ RPA than other 2 groups | Yes | Yes, no effects involving gender found | Yes; results remain when subjects with lifetime anxiety diagnoses are removed from analysis |

| Dawson et al. (1997) | 117 infants (52 female), 54 with MDD mothers and 63 non-MDD mothers | Not reported | 13-15 months | LM; P4-P3 | DSM-III-R criteria | No significant findings | Yes | Yes; Male infants of non-MDD mothers ↑ RPA than female infants; Female infants of MDD mothers ↑ RPA than male infants of MDD mothers | Yes, anxiety accounted for in analyses |

| Debener et al. (2000) | 15 current MDD (10 female); 22 controls (15 female) | 33 right; 4 left | 23-64 | LM; P4-P3 | ICD criteria | No significant findings | Yes | No | No |

| Deslandes et al. (2008) | 22 depressed and 14 controls | Right | > 60 | LE; P4-P3 | DSM-IV criteria | No significant findings | Yes | No | No |

| Diego et al. (2001) | 163 women | 83% right | M = 23 (SD = 5) | Cz; P4-P3 | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | No significant findings | Reported for frontal, not parietal EEG analyses | No | No |

| Diego et al. (2004) | Babies of 20 prepartum and postpartum depressed mothers (58% male), 20 prepartum depressed mothers (35% male), 20 postpartum depressed mothers (40% male), and 20 non-depressed mothers (40% male) | Not reported | M = 1.7 weeks (SD = 0.8 weeks) | Cz; P4-P3 | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | No significant findings | No | No | No |

| Field et al. (1995) | 17 infants of depressed mothers; 17 infants of non-depressed mothers | Right-handed parents | 3-6 months | Cz; P4-P3 | BDI and Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children | No significant findings | Yes | No | No |

| Graae et al. (1996) | 16 female suicide attempters; 22 female controls | Right | 12-17 | Nose; P4-P3 | BDI and Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children | ↓ RPA linked to higher suicidal intent, not depressive symptoms | Yes | No | No |

| Harmon-Jones et al. (2002) | 72 (37 female) | Right | Not reported | LE; P4-P3 | General Behavior Inventory Depression scale | No significant findings | Reported for frontal, not parietal EEG analyses | No | Accounted for baseline reported fear |

| Henriques & Davidson (1990) | 6 euthymic depressed patients (5 female); 8 controls (6 female) | Right | Depressed M = 37.4, SD = 9.5; Controls M = 34.7, SD = 3.4 | AVG, Cz, LM; P4-P3 | Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia according to Research Diagnostic Criteria | MDD group ↓ RPA than control group | Yes | No | No |

| Henriques & Davidson (1991) | 15 MDD patients (8 female); 13 controls (9 female) | Right | 31-57 | AVG, Cz, LE; P4-P3 | Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia according to Research Diagnostic Criteria | No significant findings | Yes | No | No |

| Jones et al. (1997) | 20 infants of depressed mothers; 24 infants of non-depressed mothers (gender not reported) | Not reported | 1-3 months | Cz; P4-P3 | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | No significant findings | Yes | No | No |

| Jones et al. (1998) | 35 infants (57.9% male) of depressed mothers; 28 infants (46.2% male) of non-depressed mothers | Not reported | 1 week | Cz, P4-P3 | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | No significant findings | Yes | No | No |

| Kentgen et al. (2000) | 11 women with current MDD and comorbid anxiety disorder; 8 women with current MDD and no anxiety disorder; 6 women with no current MDD and an anxiety disorder; 10 female controls | Right | 12-19 | Cz, Nose; P4-P3, P8-P7 | DSM-IV criteria | Subjects with MDD but no anxiety disorder showed ↓ RPA than LPA | Yes | No | Yes; addressed in main analysis with anxiety groups |

| Mathersul et al. (2008) | 428 (214 female) separated into Normal (n = 52), Depressed (n = 52), Anxious (n = 52) and Comorbid (n = 52) groups | Not reported | 18-60 | AVG; T6-T5 and P4-P3 averaged together | Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (21 item version) depression scale | Depressed and comorbid anxiety-depression groups ↑ RPA than control group | Yes | None examining gender × group to predict EEG | Yes; addressed in main analysis with anxiety groups |

| Metzger et al. (2004) | 50 female Vietnam War nurse veterans, 18 with current PTSD (9 with comorbid lifetime MDD), 14 with past PTSD (7 with comorbid lifetime MDD), and 18 with no PTSD (5 with lifetime MDD). All groups included other comorbid anxious disorders. | Right | M = 53.7, SD = 2.8 | LE; P4-P3 | DSM-IV; Clinician- Administered PTSD Scale; Symptom Checklist-90-Revised | Higher PTSD arousal symptoms ↑ RPA; PTSD arousal and PTSD arousal by depression interaction accounted for 25% of the variance in RPA | No. | No | Yes. Discussed failure to find link between higher depression symptoms ↓ RPA may be due to lack of depressed subjects without high arousal |

| Miller et al. (2002) | 55 with child onset MDD or dysthymia (28 female); 55 controls (38 female) | 85% right-handed | Depressed M = 26.0 (SD = 3.2); Control M = 27.2 (SD = 5.8) | AVG; P4-P3, P8-P7 | DSM-III and DSM-IV | No significant findings | Yes | Did examine them in frontal regions but unclear with regard to parietal | Yes; anxiety symptoms did not moderate results |

| Nitschke et al. (1999) | 9 anxious apprehension (6 female), 19 anxious arousal (10 female), 12 depressed (9 female), 13 comorbid (6 female), 14 (8 female) | Right | 17-20 | LM; P4-P3 | Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire, Anhedonic Depression scale | No significant findings for depressed group once 2 male outliers were removed | Yes | Yes, no gender effects emerged | Yes; addressed in main analysis with anxiety groups |

| Pössel et al. (2008) | 80 adolescents (35 female) | Right | 13-15 | Nose; P4-P3 | Depression-Screening Questionnaire and Self-Rating Questionnaire for Depressive Disorders based on ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria | ↑ RPA predicted depression symptoms 12 months later | No | No | Yes, accounted for anxiety in depression analyses |

| Reid et al. (1998) | Study 1: 19 low BDI women and 17 high BDI women; Study 2: 13 women with MDD and 14 controls | Right | Study 1: Low BDI group M = 19.1 (SD = 1.1) and High BDI group M = 17.9 (SD = 0.2); Study 2: MDD group M = 27.5 (SD = 8.1) and control group M = 27.6 (SD = 7.5) | AVG, Cz, LM; P4-P3 | Study 1: BDI; Study 2: DSM-III-R | Study 1: No significant findings; Study 2: MDD group ↓ RPA than control group (LM) | No | No | No |

| Schaffer et al. (1983) | 6 high BDI scorers (4 female); 6 low BDI scorers (4 female) | Not reported | Not reported | Cz; P4-P3 | BDI | No significant findings | No | No | No |

| Shankman et al. (2005) | 12 low positive emotionality (PE; 58% female) and 17 high PE group (44% female) | 73.2% right-handed | Age 3 and follow-up at age 5-6 | LM; P4-P3, P8-P7 | Positive Emotionality score based on tests in the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery | Low PE group showed ↓ RPA than LPA | Yes | Yes, no gender effects emerged | Neuroticism not related to asymmetry |

| Tomarken et al. (2004) | 25 offspring of MDD mothers (14 female); 13 offspring of mothers with no MDD (6 female) | Right | 12-14 | AVG, Cz, LE; P4-P3 | DSM-III-R | High risk group associated with ↑ RPA (Cz) | Reported for frontal, not parietal EEG analyses | Yes, but did not mention gender differences in parietal asymmetry | No |

| Volf & Passynkova (2002) | 31 MDD/SAD patients (29 females); 30 matched controls | Right | 28-55 | LE; P4-P3 | DSM-III-R | MDD/SAD group ↓ BPA than controls | Yes | No | No |

Notes: MDD= major depressive disorder. LPA = left parietal activity. RPA = right parietal activity. BPA = bilateral parietal activity. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory. DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. ICD= International Classification of Diseases. STAI = State Trait Anxiety Inventory. SAD = seasonal affective disorder. AVG = average reference. LE = linked ears reference. LM = linked mastoids reference.

In addition to heterogeneity in symptom presentation, sex differences in depression may influence patterns of regional brain activity. Most resting EEG asymmetry studies of depression that examined differences in parietal activity have utilized only female samples (Allen et al., 1993; Diego et al., 2001; Graae et al., 1996; Kentgen et al., 2000; Reid et al., 1998; Volf & Passynkova, 2002) or predominantly female samples, thereby lacking the power to reliably examine sex differences (Blackhart et al., 2006; Debener et al., 2000; Deslandes et al., 2008; Henriques & Davidson, 1991; Nitschke et al., 1999; Schaffer et al., 1983). Although there is some evidence that sex differences may be an important factor in frontal EEG asymmetry and its relationship to depression (e.g., Miller et al., 2002; Tomarken et al., 2004), parietal asymmetry (the focus of this report) has not been examined with respect to sex differences (with the exception of Bruder et al., 2007, who found no differences in parietal asymmetry between women and men with and without risk for depression). Examining sex differences in depression and brain asymmetry is important, since depressed men and women appear to display opposing patterns of frontal EEG activity that may be differentially associated with risk for depression (e.g., Miller et al., 2002; Stewart, Bismark, Towers, Coan, & Allen, 2010). Null results found in studies of clinical MDD that pool similar numbers of women and men could be due to opposing patterns of parietal activity that cancel out when sex effects are not examined (e.g., Henriques & Davidson, 1991). Furthermore, EEG asymmetry results in the unpredicted direction (relatively higher right parietal activity predicting depression symptoms one year later; Pössel, Lo, Fritz, & Seemann, 2008) could be due to a higher number of male than female participants included in the study.

The present investigation addressed these issues of sample-specific variability by recruiting a substantial sample of depressed individuals (31% male) without comorbid anxiety disorders to examine whether relatively lower right parietal activity at rest would similarly characterize women and men with a lifetime diagnosis of MDD. Additional analyses determined whether lifetime MDD results were due to a diagnosis of current MDD versus past MDD. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were included in analyses to 1) confirm that EEG asymmetry findings were not simply due to current distress among those with lifetime MDD and 2) attempt to replicate null EEG asymmetry findings using dimensional questionnaire measures of depression. In addition, since parietal EEG asymmetry is thought to reflect arousal-related processes, the present study examined whether an index of arousal (recent caffeine intake) moderated the relationship between parietal EEG asymmetry and depression in men and women. Resting EEG was collected eight times, twice per day on four separate days to ensure measurement of trait-related variance associated with parietal asymmetry. In addition, asymmetry scores were calculated for four reference derivations (average, current source density, Cz, and linked mastoid) to replicate research demonstrating convergent results for parietal asymmetry across EEG reference montages (e.g., Hagemann et al., 2001; Henriques & Davidson, 1990).

Method

Participants

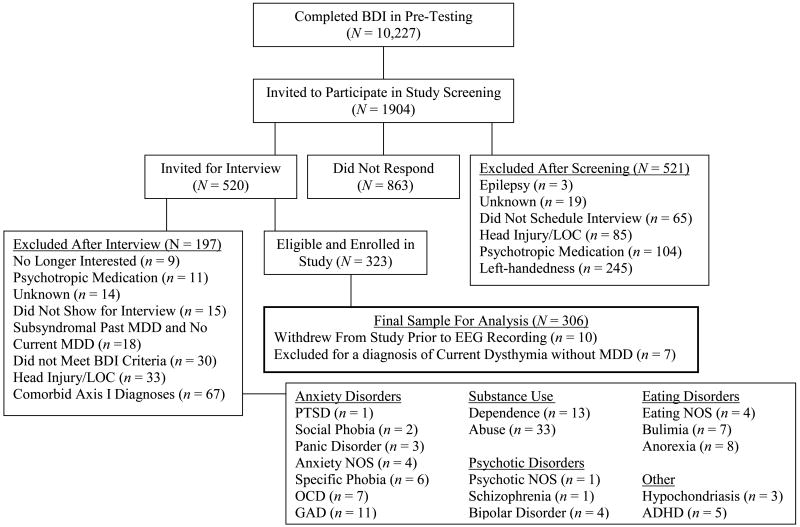

A total of 306 participants (95 male, 73% Caucasian; also reported in Stewart et al., 2010) with an age range of 17 to 34 years (M = 19.1, SE = 0.1) were enrolled in the study from a possible pool of over 10,000 individuals on the basis of their scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961) completed during pre-testing in a large introductory psychology course or online after learning about the study from a flier or referral source (please see Figure 1 for a detailed flow chart summarizing study recruitment over a four year period). Individuals were selected to span the full range of depressive severity (from absent to full clinical levels as well as ranges in between), and participated in a phone screening session administered by a post-bachelors project manager to screen for preliminary inclusion and exclusion criteria. To be eligible, individuals were required to be strongly right-handed (a score greater than 35 on the 39 point scale of Chapman & Chapman, 1987) and to report no history of: head injury with loss of consciousness greater than 10 minutes, concussion, epilepsy, electroshock therapy, use of current psychotropic medications, and active suicidal potential necessitating immediate treatment (although participation in current psychotherapy was allowed). Those passing this brief phone screen were invited for an intake interview, administered by a trained graduate clinical rater. Individuals were enrolled in the study if the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID, First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) indicated that they did not meet criteria for any DSM-IV Axis I disorder other than lifetime MDD and comorbid current dysthymia. Inter-rater reliability analyses (performed by clinical interviewers and the first and last authors) for a randomly selected 10% of SCIDs demonstrated inter-rater agreements of 96% (Kappa = .81) for current MDD diagnoses and 96% (Kappa = .91) for past MDD diagnoses. The sample of individuals with lifetime MDD was moderately impaired; with data available from 129 of the 143 with lifetime MDD, the number of major depressive episodes averaged 3.2 (SD = 3.1); with data available from 44 of the 62 with current MDD, the approximate length of the current episode was 107 days (SD = 101 days). The lifetime MDD+ group was further separated into a current MDD+ group (consisting of all participants with current MDD, regardless of past MDD status) and a past MDD+ group (consisting of participants with past MDD but not current MDD or current dysthymia) to examine whether lifetime MDD results were actually due to current symptoms (indicating a state, not a trait depression effect).1

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant screening and enrollment. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory. LOC = Loss of consciousness. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. NOS = Not Otherwise Specified. OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder. ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

Symptoms of depression and anxious apprehension for all groups (see Table 2) were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960; intra-class correlation of inter-rater agreement of .95 for 10% of randomly selected HRSD interviews in the present sample), and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990). Internal consistency reliability for all questionnaires ranged from acceptable to high in the current sample (Cronbach's alpha = .90 for BDI-II, .84 for HRSD, .95 for PSWQ). In addition to measures of depression and anxiety, caffeine consumption was used as a proxy for current arousal. Participants indicated the recency of their caffeine intake by answering the question “When was the last time you consumed caffeine? 0 = I have not used any since my last visit, 1 = earlier this week, but not yesterday, 2 = yesterday before 5pm, 3 = yesterday evening after 5pm, 4 = today.” Caffeine intake ratings were averaged across sessions for each participant to obtain an index of general caffeine consumption.

Table 2.

Group Demographics

| MDD/BDI Status | Group | BDI-II M (SE) |

HRSD M (SE) |

PSWQ M (SE) |

CAFFEINE M (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime MDD+ (n = 143)a |

Current MDD+ | ||||

| Men (n = 18) | 22.2 (1.6) | 13.3 (1.1) | 52.4 (2.9) | 2.5 (0.2)b | |

| Women (n = 44) | 24.5 (1.1) | 16.4 (0.7) | 60.5 (1.9) | 2.2 (0.1) | |

| Past MDD+ | |||||

| Men (n = 20) | 9.3 (1.5) | 6.1 (1.1) | 49.3 (2.8) | 2.7 (0.3) | |

| Women (n = 55) | 12.3 (0.9) | 8.0 (0.6) | 54.3 (1.7)b | 2.5 (0.2) | |

| Lifetime MDD- (n = 163) |

Men (n = 56) | 5.7 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.6) | 41.4 (1.7) | 2.5 (0.2) |

| Women (n = 107) | 6.2 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.4) | 45.9 (1.2)b | 2.2 (0.1) | |

Note. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder. BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory II. HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire. CAFFEINE = Ordinal Scale of recency of use ranging from 0 (not since last visit) to 4 (today).

Six participants (1 male) with past MDD and current dysthymia are included in lifetime MDD group analyses but not current/past MDD+ group analyses.

One participant did not complete the scale.

To examine whether groups differed in depression, anxious apprehension, and arousal, univariate ANOVAs were computed with current MDD status (current MDD+, past MDD+, MDD-) and biological sex as between-subjects variables and each questionnaire score as the dependent variable. Effect size (Cohen's d) is reported for significant differences between groups. A main effect of current MDD status emerged for BDI-II (F(2, 294) = 125.5, p < .001), HRSD (F(2, 294) = 98.3, p < .001) and PSWQ (F(2, 292) = 23.5, p < .001), indicating that 1) the current MDD+ group endorsed higher depression scores than the past MDD+ group (both p < .001; BDI-II d = 1.66 and HRSD d = 1.78), and 2) current MDD+ and past MDD+ groups endorsed higher depression and anxious apprehension scores than the MDD- group (all p < .001; BDI-II d = 2.38 and .65, HRSD d = 1.69 and .42, and PSWQ d = .96 and .60, respectively). In addition, a main effect of sex emerged for BDI-II (F(1, 294) = 4.2, p = .04, d = .26), HRSD (F(1, 294) = 6.5, p = .01, d = .32), and PSWQ (F(1, 292) = 11.6, p < .01, d = .43), indicating that women had higher symptom scores than men. No effects emerged for caffeine intake (p > .28).

EEG Data Collection and Reduction

Two resting EEG sessions were completed during each visit, on four separate days with no fewer then 24 hours between visits, and with all four visits completed within a 14 day period.2 Each resting EEG session was recorded for eight minutes in one-minute periods of eyes-open (O) and eyes-closed (C), in one of two counterbalanced orders (OCCOCOOC or COOCOCCO). EEG data were collected continuously for each eight-minute resting session with a 64-channel NeuroScan Synamps2 (Charlotte, NC) amplifier and acquisition system using Ag-AgCl electrodes, a 1000 Hz sampling rate, and a gain of 2816, with bandpass from DC to 200 Hz prior to digitization. EEG data were acquired with an online reference site immediately posterior to Cz and subsequently re-referenced offline to four references: 1) average of all EEG leads = AVG, 2) current source density = CSD (using algorithms from Kayser & Tenke, 2006 and based on the spherical spline approach summarized by Perrin, Pernier, Bertrand, & Echallier, 1989; Perrin, Pernier, Bertrand, & Echallier, 1990), 3) Cz, and 4) averaged (“linked”) mastoids = LM. The international 10-20 system was utilized for electrode placement and two electrooculogram (EOG) channels (horizontal: outer canthi; vertical: superior and inferior orbit of the left eye) were collected for ocular artifact rejection. All impedances were kept under 10K Ohms.

Before data reduction was implemented using custom scripts in Matlab (release 2007b, The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA), resting EEG files were visually inspected to remove intervals contaminated with movement and muscle artifacts. EEG files were then epoched into 117 2.048 seconds length epochs for each minute of data, overlapping by 1.5 seconds to compensate for the minimal weight applied to the end of the epoch by the use of the Hamming window function, retaining only epochs that did not overlap rejected segments due to artifacts. Following epoching, a blink rejection algorithm rejected additional data segments where ocular activity exceeded +/- 75 microvolts in the vertical EOG, and an artifact rejection algorithm rejected segments with large, fast deviations in amplitude (e.g., spikes) and DC steps in any channel. Subsequently, a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was applied to all artifact-free epochs. All 2.048 second epochs were first baseline adjusted by removing the mean of all samples in the epoch, effectively removing the large DC component prior to the FFT. The power spectra from all artifact-free epochs across all eight minutes were averaged to provide a summary spectrum for each resting session (range of artifact-free epochs per subject entered into the FFT for each single resting session = 44-931, lifetime MDD+ men: M = 489.0, SE = 9.3, lifetime MDD- men: M = 498.6, SE = 8.7, lifetime MDD+ women: M = 446.9, SE = 6.1, lifetime MDD- women: M = 444.3, SE = 5.3).

Finally, total alpha power (8-13 Hz) was extracted from the spectrum and an asymmetry score for each resting session was then calculated for each site by subtracting the natural log transformed scores (i.e., ln[Right] – ln[Left]) for each homologous left and right pair (FP1 & FP2, AF3 & AF4, F7 & F8, F5 & F6, F3 & F4, F1 & F2, FT7 & FT8, FC5 & FC6, FC3 & FC4, FC1 & FC2, T7 & T8, C7 & C6, C3 & C4, C1 & C2, TP7 & TP8, CP5 & CP6, CP3 & CP4, CP1 & CP2, P7 & P8, P5 & P6, P3 & P4, P1 & P2, PO7 & PO8, PO5 & PO6, PO3 & PO4, O1 & O2). Higher asymmetry score values are thought to reflect relatively greater left than right parietal activity (i.e., relatively greater right than left alpha; cf. Allen et al., 2004). The present study will be framing results in terms of right, not left, parietal activity because previous research points to right parietal dysfunction in depressed individuals (e.g., Heller & Nitschke, 1997, 1998), with lower scores thus reflective of relatively greater right activity. Asymmetry scores for the eight resting sessions (two resting sessions within each day) were then averaged together to create a trait measurement of regional brain activity. Separate asymmetry scores for each of four reference montages were utilized in analyses, resulting in four asymmetry scores per participant at each homologous pair. Although asymmetry scores were computed for all homologous pairs of channels, analyses for the present study were performed on a specific subset of those pairs (P2-P1, P4-P3, P6-P5, P8-P7) that correspond to a region commonly studied in the parietal asymmetry literature (P4-P3; e.g., Bruder et al., 1997, Shankman et al., 2005) as well as pairs of channels that neighbor P4-P3 to add specificity to the nature of parietal asymmetry as a function of lifetime MDD status.3 Intraclass correlations indicated that parietal EEG asymmetry scores were highly stable across the eight resting sessions for each reference montage (AVG range = .84-.89 across parietal pairs; CSD range = .87-.91; Cz range = .81-.85; LM range = .77-.82).

Results

Lifetime MDD Status – EEG Asymmetry Analysis

To examine the relationship between lifetime MDD status and parietal EEG asymmetry, a full factorial mixed linear model (SAS 9.2, Gary, NC) was performed. Lifetime MDD status (past and/or current MDD = lifetime MDD+, never depressed = lifetime MDD-) and biological sex (male, female) were between-subjects variables, whereas reference (4: AVG, CSD, Cz, and LM), and channel (4: P2-P1, P4-P3, P6-P5, P8-P7) were within-subjects variables. EEG asymmetry score based on total 8-13 Hz alpha power was the dependent variable. Effects of interest based on prior work (e.g., Bruder et al., 1997; Stewart et al., 2009) were: 1) a main effect of lifetime MDD, and 2) a lifetime MDD by sex interaction. Effect size (Cohen's d) is reported for significant differences between MDD+ and MDD- groups.

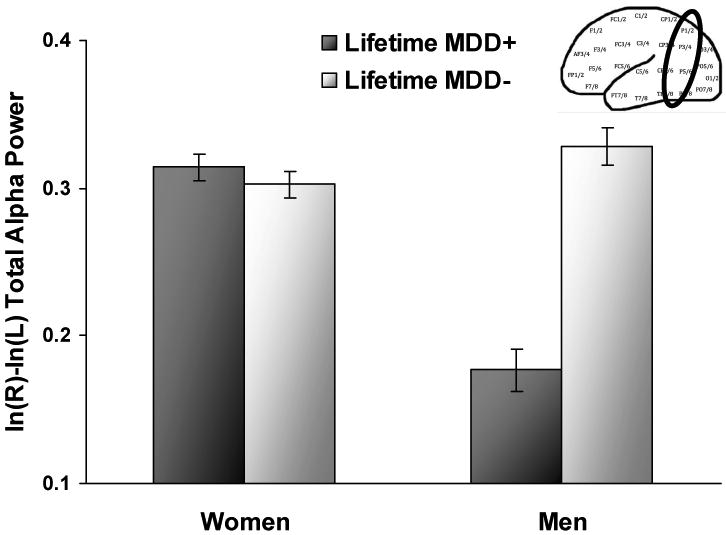

Results revealed several effects that were not of primary interest that will be reported first, with those involving MDD status being further described. Main effects of reference (F(3, 906) = 60.7, p < .001) and channel (F(3, 906) = 157.4, p < .001) were qualified by a reference by channel interaction (F(9, 2718) = 7.1, p < .001). Most importantly, the main effects of lifetime MDD (F(1, 302) = 37.3, p < .001) and sex (F(1, 302) = 23.9, p < .001) were qualified by a lifetime MDD by sex interaction (F(1, 302) = 51.1, p < .001), and follow-up linear mixed models for each sex separately (see Figure 2) indicated that lifetime MDD+ men (n = 39) displayed relatively greater right parietal activity than lifetime MDD- men (n = 56) (p < .001, d = 1.66), whereas lifetime MDD+ women (n = 104) did not differ from lifetime MDD- women (n = 107) (p > .34). These effects were not moderated by channel pair (p > .08) or reference (p > .91).

Figure 2.

Parietal alpha asymmetry scores (8-13 Hz) as a function of lifetime MDD status and sex collapsed across channel and reference. Higher values on the asymmetry score putatively reflect greater relative left or less relative right activity. Error bars reflect standard error.

Current MDD Status

A follow-up full factorial linear mixed model was run to examine whether parietal EEG asymmetry results for lifetime MDD and sex differed as a function of current versus past MDD status. Current MDD status (current MDD+ = all participants with current MDD, regardless of past MDD status; past MDD+ = participants with past MDD but not current MDD or current dysthymia; MDD- = participants without current and past MDD and dysthymia) and sex were between-subjects variables. Within-subjects variables were reference and channel. The interaction of interest was the current MDD status by sex interaction.

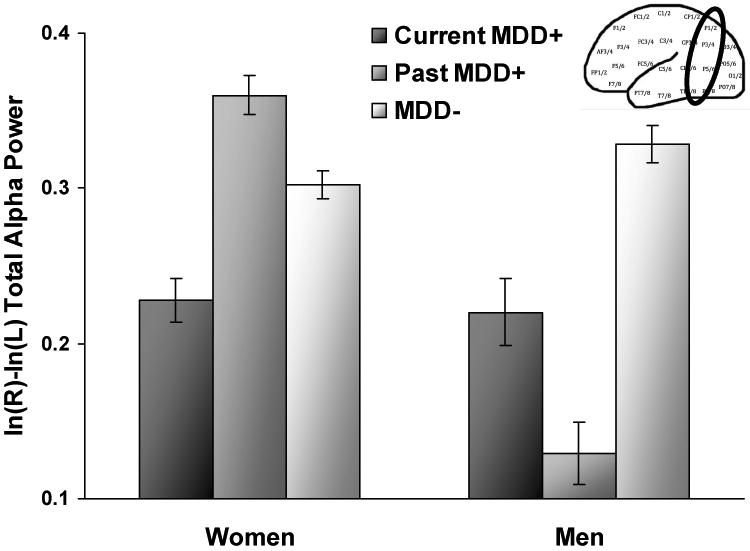

Results (see Figure 3) indicated that a current MDD status by sex interaction emerged (F(2, 294) = 42.4, p < .001), and follow-up mixed models performed for each sex separately demonstrated that current MDD+ men (n = 18) and past MDD+ men (n = 20) displayed relatively greater right parietal activity than MDD- men (n = 56) (both p < .001, d = 1.18 and 2.18, respectively). In addition, past MDD+ men showed relatively greater right parietal activity than current MDD+ men (p < .001, d = .99). Women demonstrated a different pattern than men, wherein past MDD+ women (n = 55) displayed relatively less right parietal activity than current MDD+ women (n = 44) (p < .001, d = 1.45) and MDD- women (n = 107; p < .001, d = .63), and current MDD+ women exhibited relatively greater right parietal activity than MDD- women (p < .001, d = .82). These findings explain why no significant asymmetry effects for lifetime MDD status were found for women: current MDD+ and past MDD+ groups show opposing patterns of parietal asymmetry (and thus cancel their effects).

Figure 3.

Parietal alpha asymmetry scores (8-13 Hz) as a function of current MDD status and sex across channel and reference. Higher values on the asymmetry score putatively reflect greater relative left or less relative right activity. Error bars reflect standard error.

Follow-Up Analysis

Current symptomatology

Two types of mixed model approaches were performed for each of three questionnaire measures: BDI-II intake, HRSD, and PSWQ. The first approach was designed to assess whether current symptomatology was in fact responsible for the current MDD status by sex EEG asymmetry effects observed, which would then suggest that EEG asymmetry would be sensitive to state levels of depression and anxiety rather than a trait indicator of risk for depression. Thus, hierarchical linear mixed models using Type 1 (rather than Type 3) sums of squares were run wherein reference, channel, and sex were entered first, followed by one questionnaire (z-scored), and a questionnaire by sex interaction (z-scored). Subsequently, current MDD status and the current MDD status by sex interaction were added to the model. If EEG asymmetry results are not due to current symptomatology, the current MDD status by sex interaction should remain significant. Parietal EEG asymmetry score was the dependent variable. Results indicated that the current MDD by sex interaction remained significant in all questionnaire analyses (BDI-II intake: F(2, 292) = 39.1, p < .001; HRSD: F(2, 292) = 40.1, p < .001; PSWQ: F(2, 290) = 46.7, p < .001), suggesting that current symptomatology cannot account for MDD asymmetry findings in women or men. In addition, BDI-II by sex (p > .54), HRSD by sex (p > .63), and PSWQ by sex (p > .40) interactions did not emerge, indicating that sex differences on these questionnaires do not meaningfully influence parietal asymmetry or mirror results for the observed current MDD by sex interaction.

The second mixed model approach was an attempt to replicate prior null results in the literature using dimensional psychopathology measures (not DSM-IV categories) to predict EEG asymmetry with Type 3 sums of squares. Each questionnaire was entered in its own full factorial mixed model with reference and channel as repeated factors, and sex as the other between-subjects factor. No effects emerged for BDI-II intake, BDI-II intake by sex, HRSD, HRSD by sex, PSWQ, or PSWQ by sex (all p > .39).

Post-hoc examination of moderators of EEG asymmetry

The relationship between an index of current arousal (caffeine intake) and parietal EEG asymmetry was explored as a function of current MDD status to determine whether it might differentially moderate patterns of parietal asymmetry in men and women and explain two effects not previously reported in the EEG asymmetry literature, namely: a) why current and past MDD+ men may exhibit relatively higher right parietal activity than MDD- men, and b) why current MDD+ women might display relatively higher right parietal activity than past MDD+ and MDD- women. A full factorial mixed model was run with current MDD and sex as between-subject factors, reference and channel as within-subject factors, and caffeine intake as the covariate. Parietal EEG asymmetry was the dependent variable. The effect of interest for each model was the current MDD by sex by caffeine intake interaction.

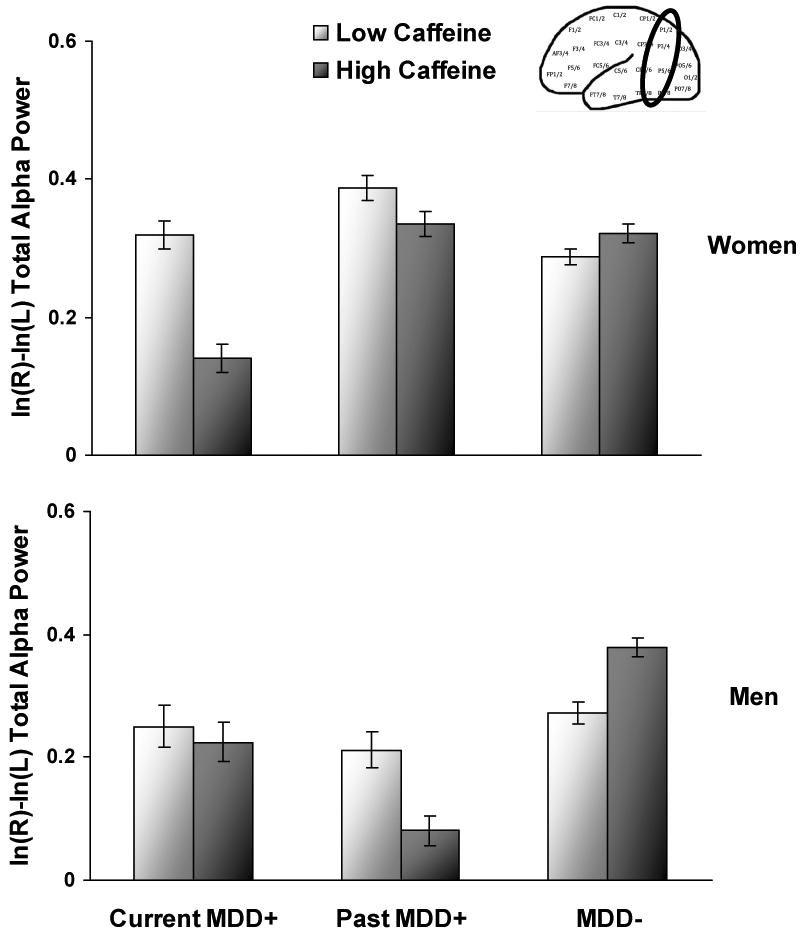

A current MDD by sex by caffeine interaction emerged (F(2, 287) = 6.0, p < .01), and follow-up mixed models run for each sex separately (see Figure 4) indicated that a current MDD by caffeine interaction was significant for men (F(2, 87) = 15.9, p < .001), showing that at low levels of caffeine intake, current MDD+ men, past MDD+ men, and MDD- men did not differ in parietal asymmetry (all p > .07), but at high levels of caffeine intake, current MDD+ men and past MDD+ men exhibited relatively greater right parietal activity than MDD- men (both p < .001; d = 1.21 and d = 2.62, respectively). In addition, past MDD+ men displayed relatively greater right parietal activity than current MDD+ men (p < .001; d = 1.17). These results suggest that the asymmetry findings for men presented in the main analyses were only apparent at higher levels of caffeine intake, and by inference, arousal.

Figure 4.

Parietal alpha asymmetry scores (8-13 Hz) as a function of current MDD status and caffeine intake averaged across sessions (illustrated by plotting estimated means +/- 1 standard deviation) for women (top panel) and men (lower panel) collapsed across channel and reference. Higher values on the asymmetry score putatively reflect greater relative left or less relative right activity. Error bars reflect standard error.

In addition, a current MDD by caffeine interaction was significant for women (F(2, 200) = 20.8, p < .001), demonstrating that at low levels of caffeine intake, current MDD+ women and MDD- women displayed relatively greater right parietal activity than past MDD+ women (p = .02 and d = .49, and p < .001 and d = .75, respectively). At high levels of caffeine intake, current MDD+ women still displayed relatively greater right parietal activity than past MDD+ women (p < .001; d = 1.47) but now also exhibited relatively higher right parietal activity than MDD- women (p < .001 and d = 1.35). Most importantly, Figure 4 illustrates that whereas caffeine intake did not moderate parietal asymmetry for past MDD+ women or MDD- women, it did moderate asymmetry for current MDD+ women, such that higher caffeine intake was linked to higher relative right parietal activity. These results account for asymmetry differences between current MDD+ and MDD- women presented in the main analyses, and these findings also partially explain initial differences between current MDD+ and past MDD+ women. Although current MDD+ women displayed relatively greater right parietal activity than past MDD+ women even at low levels of caffeine, the effect size between groups became much larger at high levels of caffeine (d = .49 compared to d = 1.47).

Discussion

The present study examined regional parietal brain activity in a large sample of depressed and non-depressed individuals without comorbid anxiety disorders in order to determine whether parietal EEG asymmetry, a potential endophenotype of MDD, is moderated by sex differences.

Patterns of parietal EEG asymmetry were indeed different between men and women with and without MDD. Results indicated that although lifetime MDD+ women did not differ from lifetime MDD- women, this null finding was due to opposing patterns of parietal asymmetry for current MDD+ and past MDD+ women. Past MDD+ women displayed relatively less right parietal activity than MDD- women, a pattern of asymmetry consistent with other parietal EEG studies of depression (e.g., Blackhart et al., 2006; Bruder et al., 1997; Kentgen et al., 2000), presenting with a medium effect size similar to those previously demonstrated in the literature (e.g., Bruder et al., 1997; Reid et al., 1999). Although current MDD+ women exhibited higher relative right parietal activity than past MDD+ women, an unexpected finding not previously described in the literature, this effect was partially moderated by caffeine intake, such that the parietal asymmetry difference between past MDD+ women and current MDD+ women was larger at high than low levels of recent caffeine consumption. Current MDD+ women did not differ from past MDD+ women on levels of caffeine intake, however, indicating that a higher amount of caffeine in the current MDD+ group was not responsible for this finding. Since prior research indicates that currently depressed patients report more anxiety than non-depressed individuals at similar levels of caffeine ingestion (Lee, Flegel, Greden, & Cameron, 1988), it could be that current MDD+ women had higher levels of anxious arousal (symptoms of panic) associated with caffeine than past MDD+ and MDD- women, reflected in higher relative right parietal activity, although additional research is needed to address this hypothesis. In summary, results for women suggest that caffeine may affect arousal processes differently as a function of current depression severity to obfuscate the underlying risk pattern for MDD, and that future work on MDD and parietal asymmetry might utilize multiple measures of arousal sensitivity to explore this possibility.

Unlike lifetime MDD results for women, lifetime MDD+ men displayed higher relative right parietal activity than lifetime MDD- men, and this large effect size was replicated in analyses of current MDD+ and past MDD+ men, who also displayed relatively greater right parietal activity than MDD- men. Recent caffeine consumption moderated the relationship between MDD status and parietal asymmetry in men, wherein current and past MDD+ men displayed relatively higher right parietal activity than MDD- men at high but not low levels of recent caffeine intake. These large parietal EEG asymmetry differences in men are new findings not previously discussed in the literature, but these results may explain null findings in parietal EEG asymmetry studies that did not examine sex differences in depression. Due to the limited research on sex differences and EEG asymmetry in individuals with MDD (thus far, only in frontal regions: Stewart et al., 2010 using the present sample, and Miller et al., 2002, using a substantial male sample), further examination is needed to evaluate the significance of parietal asymmetry in men.

Unlike parietal EEG asymmetry results for DSM-IV-defined depression categories, findings for dimensional measures of current depression symptoms (BDI-II and HRSD) were non-significant, replicating other studies finding null results with depression scales (e.g., Diego et al., 2001; Harmon-Jones et al., 2002; Nitschke et al., 1999; Reid et al., 1998), suggesting that parietal EEG asymmetry could be linked to a more enduring trait-like factor of past depression, as parietal results for women indicate. In addition, no relationship between anxious apprehension (PSWQ) and parietal asymmetry were found, replicating research finding no hemispheric differences associated with worry at rest (Nitschke et al., 1999).

Implications of Sex Differences

Relatively higher right than left parietal EEG activity is thought to reflect higher levels of emotional arousal. Since men with current and/or past depression in the present study exhibited relative right parietal EEG activity (and women with past depression showed the opposite pattern), results of the present study suggest that depressed men, regardless of current depression status, might possess higher levels of anxious arousal than depressed women. Prior research, however, demonstrates the opposite pattern. First, depressed women have a higher prevalence of panic attacks than depressed men, and women with depression also report higher incidence of palpitations and tremor/shaking, consistent with panic disorder/attacks (Angst et al., 2002). Second, women have higher comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorders than men (e.g., Breslau, Schultz, & Peterson, 1995; Howell, Brawman-Mintzer, Monnier, & Yonkers, 2001).

Complicating the clinical picture further is the assertion that two types of anxiety, anxious apprehension and anxious arousal, are associated with opposing patterns of EEG asymmetry, with anxious apprehension linked to asymmetry in favor of relatively greater left hemisphere activity, and anxious arousal associated with asymmetry in favor of relatively greater right hemisphere activity (e.g., Heller & Nitschke, 1998). Although present findings indicate that sex differences in anxious apprehension did not account for parietal EEG asymmetry differences between depressed men and women, the present study did not include a measure of anxious arousal, nor did it include depressed individuals with comorbid anxiety disorders, so it must remain an empirical question as to whether higher incidence of particular types of anxiety/anxiety disorders in depressed women and men influence differential patterns of parietal EEG asymmetry.

Parietal EEG Asymmetry: An Endophenotype for Depression?

To be an endophenotype for depression, parietal EEG asymmetry should be specific to depression and present as a trait-like feature, independent of state factors (Gottesman & Gould, 2003; Iacono, 1998). Results of the present study do not produce strong evidence that reduced right parietal EEG activity is a risk marker for depression, since parietal EEG asymmetry did not function as a trait independent of state factors. Although women with a past history of MDD displayed lower relative right parietal activity regardless of current arousal level (as indexed by recent caffeine consumption), women with current MDD and men with current and/or past MDD showed higher, not lower, relative right parietal activity, suggestive of physiological hyperarousal, not underarousal. In addition, the fact that depressed men differed from non-depressed men only at high but not low levels of recent caffeine intake (current arousal) indicate that higher right parietal EEG activity is dependent on state arousal. Reduced right parietal EEG activity, however, may be a marker for features associated with MDD pertaining to a subtype of anxiety or underarousal, warranting further explication and examination. Since a measure of anxious arousal was not included in the present study, it is possible that, even though no participants met criteria for DSM-IV anxiety disorders, anxious arousal symptoms could alone or in conjunction with anxious apprehension, moderate results for depressed participants, such that individuals with lifetime MDD and low arousal might demonstrate relatively less right parietal activation.

Strengths, Limitations, and Synopsis

The design of the present study was beneficial for examining the relationship between MDD status and parietal EEG asymmetry due to the recruitment of a substantial sample of medically healthy, medication-free men and women with no comorbid anxiety disorders. In addition, multiple sessions of EEG recording provided a reliable estimate of trait asymmetry effects that were consistent across medial and lateral regions of the parietal cortex. Parietal EEG results were also highly consistent across all four reference derivations, supporting the assertion that references should possess similar signal-to-noise ratios in posterior brain regions where EEG alpha activity is strongest (Hagemann et al., 2001).

The present study is the first to examine parietal EEG asymmetry differences in a large sample of men and women with current versus past MDD to attempt to disentangle state versus trait MDD effects. The divergent patterns of EEG asymmetry for current MDD versus past MDD, particularly in women suggests that relatively less right parietal activity at rest may actually be an enduring risk factor for depression (characterizing those with past MDD) but not an indicator of current severity (as it does not characterize those with current MDD). A limitation of this study is the failure to measure specifically symptoms of anxious arousal, which could potentially moderate the relationship between current MDD status and EEG asymmetry in women, since higher anxious arousal symptoms are linked to relatively greater right parietal activity in women and men with current MDD.

Limitations of the present study include a younger cohort who was not actively seeking treatment for depression, suggesting that these findings may not be assumed to apply for later-onset depression, or severe cases of depression in individuals receiving inpatient or outpatient treatment. Our early-onset sample, however, was moderately depressed, as indicated by number of major depressive episodes experienced and length of current depressive episodes, and thus might be expected to have a recurrent or chronic course of depression (cf. findings with chronic depression, Klein et al., 1999), potentially generalizing to depression later in life. Although results of the current study are most generalizable to a young medication-free sample without comorbid Axis I disorders, the fact that indices of arousal moderate patterns of parietal asymmetry in depressed men and women suggest that the present results may extend to depressed individuals with comorbid conditions associated with anxiety, which comprise a large percentage of the MDD population (e.g., Kessler et al., 2003).

In the largest study of parietal EEG asymmetry of MDD to date, men and women exhibited differential patterns of regional brain activity as a function of current and past depression status across four EEG reference montages, indicating that a) parietal EEG asymmetry differences in MDD are robust and b) future studies of parietal brain asymmetry and risk for depression must take sex differences into consideration. In addition, the strength of an arousal index (recent caffeine consumption) as a moderator of parietal asymmetry in men and women indicate that comorbidity of depression and anxiety symptoms may be important in the study of endophenotypic markers of depression vulnerability.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-MH066902) and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD) to John Allen. The authors wish to thank Andrew Bismark, Eliza Fergerson, Jamie Velo, Dara Halpern, Craig Santerre, Eynav Accortt, Amanda Brody, and Jay Hegde for assistance with subject recruitment, and myriad research assistants who helped to collect and review EEG data.

Footnotes

Within the lifetime MDD+ group (n = 143), the following diagnoses were met: 14 (5 male) for current MDD only, 75 (20 male) for past MDD only, 39 (10 male) for current MDD and past MDD, 2 (0 male) for current MDD and current dysthymia, 6 (1 male) for past MDD and current dysthymia, and 7 (3 male) for current MDD, past MDD, and current dysthymia. A total of six participants with diagnoses of past MDD and current dysthymia that were included in lifetime MDD analyses were excluded from current/past MDD analyses due to high levels of dysphoric DSM-IV symptomatology that did not meet criteria for a current MDD diagnosis.

Of the 21 participants who did not complete their sessions within a 2 week time frame, 15 completed all sessions within 16 days, whereas the remaining 6 completed all sessions within 18-20 days. In addition, 7 participants attended fewer than all four EEG assessment days (N = 4 three days, N = 1 two days, N = 2 one day), but these individuals were included in mixed linear model analyses that successfully accommodated missing data.

Resting EEG asymmetry results for frontal regions alone were previously reported in Stewart et al. (2010) and therefore were not included in this manuscript.

References

- Allen JJB, Iacono WG, Depue RA, Arbisi P. Regional electroencephalographic asymmetries in bipolar seasonal affective disorder before and after exposure to bright light. Biological Psychiatry. 1993;33:642–646. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90104-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JJB, Coan JA, Nazarian M. Issues and assumptions on the road from raw signals to metrics of frontal EEG asymmetry in emotion. Biological Psychology. 2004;67:183–218. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Gamma A, Gastpar M, Lepine JP, Mendlewicz J, Tylee A. Gender differences in depression. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2002;252:201–209. doi: 10.1007/s00406-002-0381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. The Beck Depression Inventory–II. San Antonio: Harcourt Assessment; 1996. http://www.pearsonassessments.com/pai/aihome.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blackhart GC, Minnix JA, Kline JP. Can EEG asymmetry patterns predict future development of anxiety and depression?: A preliminary study. Biological Psychology. 2006;72:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Schultz L, Peterson E. Sex differences in depression: A role for preexisting anxiety. Psychiatry Research. 1995;58:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02765-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder GE. Frontal and parietotemporal asymmetries in depressive disorders: Behavioral, electrophysiologic and neuroimaging findings. In: Hugdahl K, Davidson RJ, editors. The asymmetrical brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2003. pp. 719–742. http://mitpress.mit.edu/main/home/default.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder GE, Fong R, Tenke CE, Leite P, Towey JP, Stewart JE, Quitkin FM. Regional brain asymmetries in major depression with or without an anxiety disorder: A quantitative electroencephalographic study. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;41:939–948. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder GE, Kayser J, Tenke CE, Leite P, Schneier FR, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM. Cognitive ERPs in depressive and anxiety disorders during tonal and phonetic oddball tasks. Clinical Electroencephalography. 2002;33:119–124. doi: 10.1177/155005940203300308. http://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2060289. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bruder GE, Tenke CE, Stewart JW, Towey JP, Leite P, Voglmaier M, Quitkin FM. Brain event-related potentials to complex tones in depressed patients: Relations to perceptual asymmetry and clinical features. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:373–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder GE, Tenke CE, Warner V, Nomura Y, Grillon C, Hille J, Weissman MM. Electroencephalographic measures of regional hemispheric activity in offspring at risk for depressive disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder GE, Tenke CE, Warner V, Weissman MM. Grandchildren at high and low risk for depression differ in EEG measures of regional brain asymmetry. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder GE, Wexler BE, Stewart JW, Price LH, Quitkin FM. Perceptual asymmetry differences between major depression with or without a comorbid anxiety disorder: A dichotic listening study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:233–239. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP. The measurement of handedness. Brain and Cognition. 1987;6:175–183. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(87)90118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Anterior electrophysiological asymmetries, emotion, and depression: Conceptual and methodological conundrums. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:607–614. doi: 10.1017/S0048577298000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Frey K, Panagiotides H, Osterling J, Hessl D. Infants of depressed mothers exhibit atypical frontal brain activity: A replication and extension of previous findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debener S, Beauducel A, Nessler D, Brocke B, Heilemann H, Kayser J. Is resting anterior EEG alpha asymmetry a trait marker for depression? Neuropsychobiology. 2000;41:31–37. doi: 10.1159/000026630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deldin PJ, Keller J, Gergen JA, Miller GA. Right-posterior face processing anomaly in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:116–121. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslandes AC, de Moraes H, Pompeu FAMS, Ribeiro P, Cagy M, Capitäu C, Laks J. Electroencephalographic frontal asymmetry and depressive symptoms in the elderly. Biological Psychology. 2008;79:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M. CES-D depression scores are correlated with frontal EEG alpha asymmetry. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:32–37. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2001)13:1<32∷AID-DA5>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Cullen C, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Prepartum, postpartum, and chronic depression effects on newborns. Psychiatry. 2004;67:63–80. doi: 10.1521/psyc.67.1.63.31251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Fox NA, Pickens J, Nawrocki T. Relative right frontal EEG activation in 3- to 6-month-old infants of “depressed” mothers. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:358–363. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.3.358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- First MG, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorder—clinical version, administration booklet. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department; 1997. http://cpmcnet.columbia.edu/dept/scid/ [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman II, Gould TD. The endophenotypic concept in psychiatry: Etymology and strategic intentions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:636–645. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graae F, Tenke C, Bruder G, Rotheram M, Piacentini J, Castro-Blanco D. Abnormality of EEG alpha asymmetry in female adolescent suicide attempters. Biological Psychiatry. 1996;40:706–713. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann D, Naumann E, Thayer JF. Psychophysiology. Vol. 38. 2001. The quest for the EEG reference revisited: A glance from brain asymmetry research; pp. 847–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann D, Naumann E, Thayer JF, Bartussek D. Does resting electroencephalograph asymmetry reflect a trait? An application of latent state-trait theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:619–641. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Abramson LY, Sigelman J, Bohlig A, Hogan ME, Harmon-Jones C. Proneness to hypomania/mania symptoms or depression symptoms and asymmetrical frontal cortical responses to an anger-evoking event. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:610–618. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler G, Drevets WC, Manji HK, Charney DS. Discovering endophenotypes for major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1765–1781. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden EP, Shankman SA, Olino TM, Durbin CE, Tenke CE, Bruder GE, Klein DN. Cognitive and temperamental vulnerability to depression: Longitudinal associations with regional cortical activity. Cognition and Emotion. 2008;22:1415–1428. doi: 10.1080/02699930701801367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heller W. Neuropsychological mechanisms of individual differences in emotion, personality, and arousal. Neuropsychology. 1993;7:476–489. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.7.4.476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heller W, Etienne MA, Miller GA. Patterns of perceptual asymmetry in depression and anxiety: Implications for neuropsychological models of emotion and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:327–333. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller W, Nitschke JB. Regional brain activity in emotion: A framework for understanding cognition in depression. Cognition and Emotion. 1997;11:637–661. doi: 10.1080/026999397379845a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heller W, Nitschke JB. The puzzle of regional brain activity in depression and anxiety: The importance of subtypes and comorbidity. Cognition & Emotion. 1998;12:421–447. doi: 10.1080/026999398379664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heller W, Nitschke JB, Etienne MA, Miller GA. Patterns of regional brain activity differentiate types of anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:376–385. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Regional brain electrical asymmetries discriminate between previously depressed and healthy control subjects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:22–31. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.99.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Left frontal hypoactivation in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:535–545. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Brain electrical asymmetries during cognitive task performance in depressed and non-depressed subjects. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;42:1039–1050. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00156-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell HB, Brawman-Mintzer O, Monnier J, Yonkers KA. Generalized anxiety disorder in women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;24:165–178. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG. Identifying psychophysiological risk for psychopathology: examples from substance abuse and schizophrenia research. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:621–637. doi: 10.1017/S0048577298980489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NA, Field T, Fox NA, Davalos M, Lundy B, Hart S. Newborns of mothers with depressive symptoms are physiologically less developed. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:537–541. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(98)90027-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NA, Field T, Fox NA, Lundy B, Davalos M. EEG activation in 1-month-old infants of depressed mothers. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:491–505. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser J, Bruder GE, Tenke CE, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM. Event-related potentials (ERPs) to hemifield presentations of emotional stimuli: Differences between depressed patients and healthy adults in P3 amplitude and asymmetry. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2000;36:211–236. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser J, Tenke CE. Principal components analysis of Laplacian waveforms as a generic method for identifying ERP generator patterns: I. Evaluation with auditory oddball tasks. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2006;117:348–368. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller J, Nitschke JB, Bhargava T, Deldin PJ, Gergen JA, Miller GA, Heller W. Neuropsychological differentiation of depression and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:3–10. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentgen LM, Tenke CE, Pine DS, Fong R, Klein RG, Bruder GE. Electroencephalographic asymmetries in adolescents with major depression: Influence of comorbidity with anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:797–802. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Schatzberg AF, McCullough JP, Dowling F, Goodman D, Howland RH, Keller MB. Age of onset in chronic major depression: Relation to demographic and clinical variables, family history, and treatment response. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;55:149–157. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MA, Flegel P, Greden JF, Cameron OG. Anxiogenic effects of caffeine on panic and depressed patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145:632–635. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.5.632. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liotti M, Mayberg HS. The role of functional neuroimaging in the neuropsychology of depression. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2001;23:121–136. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.1.121.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathersul D, Williams LM, Hopkinson PJ, Kemp AH. Investigating models of affect: Relationships among EEG alpha asymmetry, depression, and anxiety. Emotion. 2008;8:560–572. doi: 10.1037/a0012811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: A proposed model of depression. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1997;9:471–481. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.471. http://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mayberg HS. Modulating dysfunctional limbic-cortical circuits in depression: Towards development of brain-based algorithms for diagnosis and optimised treatment. British Medical Bulletin. 2003;65:193–207. doi: 10.1093/bmb/65.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger LJ, Paige SR, Carson MA, Lasko NB, Paulus LA, Pitman RK, Orr SP. PTSD arousal and depression symptoms associated with increased right-sided parietal EEG asymmetry. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:324–329. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Fox NA, Cohn JF, Forbes EE, Sherrill JT, Kovacs M. Regional patterns of brain activity in adults with a history of childhood-onset depression: Gender differences and clinical variability. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:934–940. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke JB, Heller W, Palmieri PA, Miller GA. Contrasting patterns of brain activity in anxious apprehension and anxious arousal. Psychophysiology. 1999;36:628–637. doi: 10.1017/S0048577299972013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke JB, Heller W, Imig JC, McDonald RP, Miller GA. Distinguishing dimensions of anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:1–22. doi: 10.1023/A:1026485530405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin F, Pernier J, Bertrand O, Echallier JF. Spherical splines for scalp potential and current density mapping. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology. 1989;72:184–187. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(89)90180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin F, Pernier J, Bertrand O, Echallier JF. Corrigenda. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology. 1990;76:565–566. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(90)90009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pössel P, Lo H, Fritz A, Seeman S. A longitudinal study of cortical EEG activity in adolescents. Biological Psychology. 2008;78:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe S, Debener S, Brocke B, Beauducel A. Depression and its relation to posterior cortical activity during performance of neuropsychological verbal and spatial tasks. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:601–611. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SA, Duke LM, Allen JJB. Resting frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry in depression: Inconsistencies suggest the need to identify mediating factors. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:389–404. doi: 10.1017/S0048577298970986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer CE, Davidson RJ, Saron C. Frontal and parietal electroencephalogram asymmetry in depressed and nondepressed subjects. Biological Psychiatry. 1983;18:753–762. http://www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps. [PubMed]

- Shankman SA, Tenke CE, Bruder GE, Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Klein DN. Low positive emotionality in young children: Association with EEG asymmetry. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:85–98. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JL, Bismark AW, Towers DN, Coan JA, Allen JJB. Resting frontal EEG asymmetry as an endophenotype for depression risk: Sex-specific patterns of frontal asymmetry. 2010 doi: 10.1037/a0019196. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Dichter GS, Garber J, Simien C. Resting frontal brain activity: Linkages to maternal depression and socio-economic status among adolescents. Biological Psychology. 2004;67:77–102. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volf NV, Passynkova NR. EEG mapping in seasonal affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;72:61–69. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuga M, Fox NA, Cohn JF, George CJ, Levenstein RM, Kovacs M. Long term stability of frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry in adults with a history of depression and controls. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2006;59:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]