Abstract

Background

We previously showed that the combination of topotecan (TPT) and carboplatin (CBP) is more effective than current chemotherapeutic combinations used to treat retinoblastoma in an orthotopic xenograft model. However, systemic coadministration of these agents is not ideal, because both cause dose-limiting myelosuppression in children.

Methods

To overcome the toxicity associated with systemic TPT and CBP, we explored subconjunctival delivery of TPT or CBP in an orthotopic xenograft model and genetic mouse model (Chx10-Cre;RbLox/Lox;p107−/−;p53Lox/Lox) of retinoblastoma. Effects of the combination of subconjunctival CBP and systemic TPT (CBPsubcon/TPTsyst) were compared with those of TPTsubcon/CBPsyst. at clinically relevant dosages.

Results

Pharmacokinetic and tumor-response studies, including analyses of ocular and hematopoietic toxicity, showed that CPBsubcon/TPTsyst is more effective and has fewer side effects than TPTsubcon/CBPsyst.

Conclusion

For the first time, we have ablated retinoblastoma and preserved long-term vision in a mouse model by using a clinically relevant chemotherapy regimen. These results may eventually be translated into a clinical trial for children with this debilitating cancer.

Keywords: retinoblastoma, topotecan, carboplatin, translational research

Introduction

Retinoblastoma is the third most common cancer in infants;1 approximately 250 to 300 cases are diagnosed annually in the United States. Advances made in noninvasive focal therapies combined with chemotherapy have transformed retinoblastoma management since the 1990s. With early detection, survival probability is approximately 90% in developed countries; in developing countries, it is only about 50%. The goal of retinoblastoma treatment is to preserve vision without compromising long-term survival and minimizing side effects. Enucleation is still common in the eye with most advanced disease in a patient with bilateral disease.

Patients with retinoblastoma have not fully benefited from advances in drug development and local delivery methods, in part, because few preclinical models faithfully recapitulate the human disease. Animal models are essential for studying retinoblastoma, because there are too few patients for large-scale clinical trials.2 The recent development of several rodent models of retinoblastoma may facilitate advances in treatment of bilateral retinoblastoma3, 4. Using an orthotopic xenograft model of retinoblastoma, we previously showed that the combination of systemic topotecan (TPTsyst) and carboplatin (CBPsyst) is more effective than the current standard of care (etoposide/vincristine/CBP).4 Unfortunately, coadministration of these agents causes intolerable toxicity in children.5

Two approaches make possible the coadministration of these agents with minimal side effects: First, administer the drugs at different times and closely monitor blood counts to ensure that myelosuppression does not reach dangerous levels. The limitation of this approach is that tumor cells are exposed to only 1 agent at a time. Second, administer one drug locally to the eye and the other systemically to minimize toxicity. Abramson and colleagues first showed that subconjunctival administration of CBP (CBPsubcon; 20 mg/eye) is a feasible treatment for retinoblastoma.6 Indeed, retinoblastoma is ideal for local delivery of chemotherapy, because the eye is readily accessible, and high intraocular concentrations can be achieved with lower systemic exposure. Although both drugs could be administered simultaneously via subconjunctival injection, we do not favor this approach for several reasons: (1) The subconjunctival space holds a finite volume, so if 2 drugs are combined, the concentration of each must be reduced. (2) Subconjunctival injections are typically performed only under anesthesia during examinations, which occur every 3 weeks. If 1 drug is delivered systemically over the course of several days, the tumor will be exposed to that agent for a longer period of time.

Here we compared the effectiveness of CBPsubcon/TPTsyst combination with that of TPTsubcon/CBPsyst. Pharmacokinetics were performed to determine which agent was better suited to subconjunctival injection. Toxicity and tumor-response experiments were also done to guide future trials. Finally, we conducted a comprehensive preclinical study of our established knockout mouse model of retinoblastoma.7 All diagnostic tests and assessments done in children with retinoblastoma were done in the mice.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and viability

Y79 and Weri1 cells were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA) and RB355 cells were obtained from Brenda Gallie. Retina cells were maintained in RPMI medium with 10% FCS.8 The Y79-Luc cell line has been described previously.4 To compare the sensitivities of retinoblastoma cell lines to different chemotherapies, we exposed each line to 14 concentrations (0.004-60 μM) of each drug for 0.5, 2, 4, 8, or 72 h. Their viability was determined with CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay Kit (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA). The luminescent signals were read by an Envision Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Genetic mouse model of retinoblastoma, orthotopic rat xenografts, and fluorescent imaging

We used the previously described Chx10-Cre;RbLox/Lox;p107−/−;p53Lox/Lox mouse model of retinoblastoma.7 For xenograft studies, newborn Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) received an intravitreal injection of 1,000 Y79-Luc cells, as described previously.4 After approximately 2 weeks, the animals were intraperitoneally injected with D-luciferin (100 mg/kg) and imaged 30 min later using a Xenogen IVIS® 200 system and Living Image Software 2 (all from Caliper LifeSciences, Hopkinton, MA). Tumor burden is directly proportional to the photons/ cm2·s. detected with the Xenogen imaging system.9 Once tumor burden reached 106 photons/cm2·s, animals were used in the pharmacokinetic studies.

Pharmacokinetic studies

Two-week-old rats were treated with TPT (10 μg per eye; GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) or CBP (100 μg/eye; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY). At serial time points (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.5, 4, and 6 h), a cardiac puncture was performed; blood was collected; and plasma was isolated. The animals were then euthanized by cervical dislocation; the eyes were removed; the vitreous collected and flash frozen; and the retinae were harvested, rinsed in saline to remove excess drug, and flash frozen.

Total TPT (lactone plus carboxylate) was quantitated by a sensitive, specific reversed-phase isocratic HPLC.10 The method was linear from 0.25 to 5000 ng/mL, and the lower limit was 0.25 ng/mL. For CBP, the concentration of total platinum in supernatants was quantitated using flameless atomic absorption spectrometry (Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 600 atomic absorption spectrometer with Zeeman background correction to measure platinum content) after diluting the matrix in water containing 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100 and 0.06% (w/v) cesium chloride.

An appropriate pharmacokinetic model was fit to the TPT or CBP plasma or vitreous concentration vs. time data using the ADAPT software, version 5.0.0. (Biomedical Simulations Resource, Los Angeles, CA).11 The areas under the TPT or CBP plasma or vitreous concentration vs. time curves from 0 to 6 h (AUC) were calculated using the parameter estimates and the log-linear trapezoidal method.

Intraocular Pressure Measurements

The intraocular pressure (IOP) of sedated mice was measured with the TonoLab Rebound Rodent Tonometer (Tonolab, Espoo, Finland). The device was held so that the probe was 1 to 4 mm from the cornea; 6 measurements were taken and averaged. IOP measurements were taken before subconjunctival injection and then at 1, 2, and 7 days thereafter.

Visual Acuity

Visual acuity was measured using the OptoMotry System (CerebralMechanics, Inc., Alberta, Canada) as described.12 All tests were performed in bright-light conditions to measure cone function. At least 2 consecutive measurements were taken 24 h before and after drug administration.

Complete Blood Counts

To assess the hematopoietic toxicity of TPT and CBP, standard complete blood counts with differential (CBC-Ds) were obtained on Day 0 and Day 6 or 10 postinjection, depending on treatment. Blood (∼30 μL) was collected from the facial vein and mixed with 30 μl ethanol. Samples were processed immediately using the FORCYTE™ Hematology Analyzer (Oxford Scientific, Oxford, CT).

Digital Retina Camera

The initial diagnosis and staging of retinoblastoma were visualized with a Kowa retinal camera (Tokyo, Japan) reconfigured with a 70 diopter lens for use with mouse eyes. To visualize the retina, whiskers were trimmed and the pupil was dilated with 1% tropicamide.

Ultrasound

The Visualsonics Vevo 770 system (Toronto, Ontario) was used for ultrasound measurements of retinoblastoma tumors. Mice were sedated with isoflurane (2%-3% in O2) and positioned on the Vevo platform. Ultrasound gel (Aquaphora) was applied to the surface of the eye, and a 708-Hz probe was used for B-mode image acquisition.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic Resonance Images (MRIs) were obtained using a 7-T Bruker Clinscan animal MRI scanner (Bruker BioSpin MRI GmbG, Ettlingen, Germany) equipped with Bruker 12s gradient (BGA12S) and a 4-channel phase-array surface coil placed on the mouse's head. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (as described above) for the duration of data acquisition. Three-dimensional Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo (MP-RAGE) protocol (TR 2500 ms; TE 2.5 ms; TI 1050 ms) was used to produce T1-weighted images (0.5-mm coronal slices) with a matrix of 256 × 146 and FOV of 30 × 20.6 mm. The initial images were read on a Siemens work station using Syngo MR B15 software (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and reviewed with MRIcro (Version 1.4) software.

Ocular histopathology

Eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C, dehydrated through an alcohol series, and washed in xylene. They were then paraffin-embedded, and 5-μm sagittal sections were cut through the optic nerve. The corneas, ciliary epithelia, retinae, and optic nerves of untreated eyes were compared with those of treated eyes at 1, 2, and 7 days after subconjunctival injection.

Statistical Methods

Significant changes in the CBC-Ds and blood chemistry tests were calculated with GraphPad software using a t-test. The survival curves were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and a log-rank test was used to compare the curves.

Results

Pharmacokinetics of subconjunctival injection of carboplatin or topotecan

Phase I clinical trials have demonstrated that CBPsubcon6 or TPTsubcon13 are well-tolerated as single agents in patients with retinoblastoma. To determine the extent of intraocular penetration and systemic exposure of each drug after subconjunctival administration in our rodent models, we performed pharmacokinetic experiments in juvenile 2-week-old rats, as described previously.4 TPT (10 μg/eye) and CBP (100 μg/eye) were administered as bilateral injections. Based on the proportional volume of human eyes vs. rat eyes, these doses were similar to those used in children.6, 13

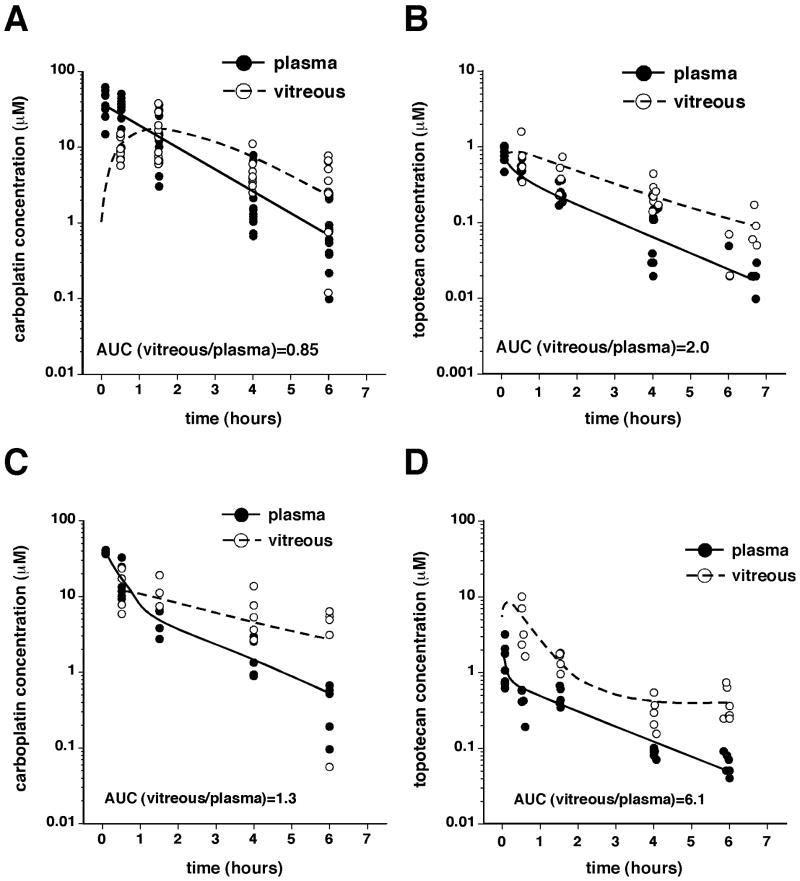

The vitreous, plasma, and retinae were harvested at several timepoints up to 6 hours after TPTsubcon or CBPsubcon, and the drug concentration was measured in each tissue. The AUCs were calculated from model parameters. Both agents efficiently penetrated the vitreous (Fig. 1A, B, Table 1); the AUC ratio (AUCvitreous/AUCplasma) for TPT was 1.98, and that for CBP was 0.85, suggesting that TPT more efficiently penetrated the vitreous.

Figure 1. Pharmacokinetics of carboplatin and topotecan delivered individually via subconjunctival injection.

(A, B) Ocular and systemic pharmacokinetic analyses of CBP (A) and TPT (B) in 2-week-old rats after subconjunctival injections of either drug in both eyes (CBP, 100 μg/eye; TPT, 10 μg/eye). (C, D) In a similar experiment performed using tumor-bearing animals, plasma and vitreous were harvested at similar time points, and the concentration vs time plot was used to fit a 2-compartment model for AUC determination.

Table 1. Ocular and systemic topotecan and carboplatin exposure in juvenile rats.

| Drug (dose) | Delivery Route | Nontumor-bearing | Tumor-bearinga | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUCplasma (μM·h) | AUCvitreous (μM·h) | Ratiob | AUCplasma (μM·h) | AUCvitreous (μM·h) | Ratiob | ||

| TPT (2 mg/kg) | Syst | 2.69 | 1.02 | 0.38 | n.a. | n.a. | |

| TPT (10 μg/eye) | Subcon | 1.14 | 2.27 | 1.98 | 1.44 | 8.78 | 6.12 |

| CBP (70 mg/kg) | Syst | 559 | 330 | 0.59 | n.a. | n.a. | |

| CBP (100 μg/eye) | Subcon | 62.7 | 53.6 | 0.85 | 32.2 | 40.7 | 1.26 |

For tumor-bearing rats, 1,000 Y79-Luc cells were injected into the vitreous at P0, and animals were monitored daily from P7. When the tumor burden reached 106 photons/cm2·s, the animals were used for the pharmacokinetics study. Tumor burden was achieved by approximately P12.

The ratio of the AUCvitreous/AUCplasma is an estimate of the ocular exposure to each drug.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the concentration vs. time curve; CBP, carboplatin; n.a., not applicable; Subcon, subconjunctival administration; Syst, systemic administration; TPT, topotecan.

Next, we evaluated the pharmacokinetics of TPTsubcon or CBPsubcon in tumor-bearing juvenile rats to determine whether the presence of a rapidly growing tumor in the vitreous altered these drugs' pharmacokinetic profiles. The vitreal penetration of CBP was not dramatically altered (AUCvitreous/AUCplasma = 1.26; Fig. 1C, Table 1). However, that of TPT increased 3 fold in the presence of tumor (AUCvitreous/AUCplasma = 6.12; Fig. 1D, Table 1). For both drugs, subconjunctival injections resulted in greater vitreous exposure than did systemic injections (Table 1).4

To measure drug exposure in the contralateral untreated eye after a single subconjunctival injection, we performed pharmacokinetics as described above. At each time point, the AUCvitreous/AUCplasma in the contralateral eye was lower than that of the injected eye and similar to values reported after systemic injections (Table 2).4

Table 2. Influence of delivery route on vitreal exposure of topotecan and carboplatin.

| Drug | AUCvitreous/AUCplasma | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraperitoneala | Subconjunctivalb (injected eye) | Subconjunctivalc (contralateral eye) | |

| Topotecan | 0.38 | 2.0 | 0.35 |

| Carboplatin | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.62 |

Values for intraperitoneal AUC ratios were previously published.4 The dose was 2 mg/kg.

In independent experiments, topotecan (10 μg/eye) and carboplatin (100 μg/eye) were injected subconjunctivally into both eyes.

In independent experiments, topotecan (10 μg/eye) and carboplatin (100 μg/eye) were subconjunctivally injected into the left eye, and the right eye was analyzed.

Cytotoxicity in retinoblastoma cell lines

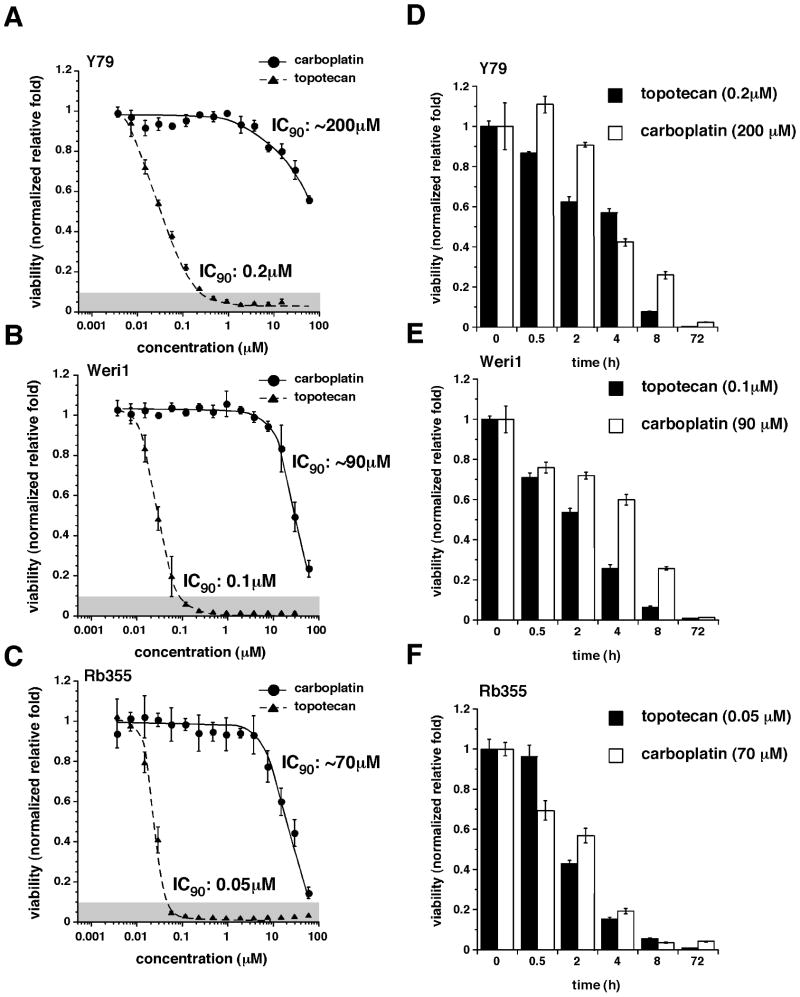

To establish a target systemic exposure for dosing in our preclinical models, we tested the cytotoxicity of 3 human retinoblastoma cell lines (Y79, Weri1, and RB355) to TPT and CBP. The starting cell density for each line was determined empirically by measuring the growth of cells after 72 h in 384-well culture dishes to ensure that they were within the linear range for the Cell Titer Glo Assay (data not shown). The IC90 of the Y79 cells after TPT treatment was about 0.2 μM (Fig. 2A); Weri1 and Rb355 cells were more sensitive, with IC90 values of 0.1 μM and 0.05 μM, respectively (Fig. 2B, C). A similar trend was observed for CBP (Fig. 2A-C).

Figure 2. Sensitivity of retinoblastoma cell lines to topotecan and carboplatin.

(A-C) Viability of retinoblastoma cells (Y79, Weri1, and RB355) after 72-h exposure to different concentrations of CBP or TPT. Each data point represents the mean and standard deviation of triplicate samples. (D-F) Viability of retinoblastoma cells exposed at the IC90 concentration of each drug for different periods. The drug was washed off, and cells were incubated for 72 h, as in (A-C). Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of triplicate samples.

Next, we determined the duration of exposure (0.5, 2, 4, 8, or 72 h) to the IC90s of the agents needed to achieve maximum cytotoxicity in each line. The cells were maintained for 72 h, and cell viability was measured (Fig. 2D-F). Ninety percent cytotoxicity was achieved in each line after about 8-h exposure to TPT (0.05-0.2 μM; Fig. 2D-F); CBP (70-200 μM) showed a similar trend when estimated IC90 values from the AUCs in Fig. 2A-C were used. Although these values are not equivalent to AUCs, they approximated the minimal sustained levels of CBP or TPT required to kill a significant proportion of retinoblastoma cells in the vitreous.

The AUCs for vitreal exposure to each agent via both routes of administration were used to determine a ratio of the 2 drugs that would be achieved with each approach. The AUCvitreous for TPTsyst (2 mg/kg) was 1.02 μM·h, which is equivalent to 0.102 μM·h for the dose of 0.2 mg/kg used in our animal studies. The AUCvitreous for CBPsubcon (100 μg/eye) was 53.6 μM·h. Therefore, the ratio in the vitreous when CBPsubcon/TPTsyst was administered was 0.1 μM TPT/53 μM CBP; when the methods of delivery were reversed, the ratio was 2.27 μM TPT/165 μM CBP. Clearly, these concentrations were not achieved in the vitreous (Fig. 1), but the overall exposure ratio is reflected in these numbers. To determine whether one ratio is more effective than the other and guide our tumor-response experiments, we performed a dose-response analysis using these 2 ratios. Each ratio showed substantial toxicity across the concentration ranges achieved in the vitreous (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Sensitivity of retinoblastoma cells to combination chemotherapy.

Retinoblastoma cells (Y79, Weri1, and RB355) were exposed to different dilutions of fixed ratios of CBP/TPT based on pharmacokinetic data for vitreal exposure of the 2 drugs after subconjunctival and systemic administration. (A) Data are plotted for dilutions of the 2 drugs at the ratio achieved in the vitreous when the CBPsubcon/TPTsyst combination is administered. The dose of TPT is plotted for each dilution. Each data point is the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments. (B) Data are plotted for dilutions of the 2 drugs at the ratio achieved in the vitreous when the reverse combination is administered. The dose of CBP is plotted for each dilution. Each data point is the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments. The gray box represents the range of drug concentration in the vitreous from pharmacokinetic experiments.

Tumor response to subconjunctival injection of topotecan or carboplatin

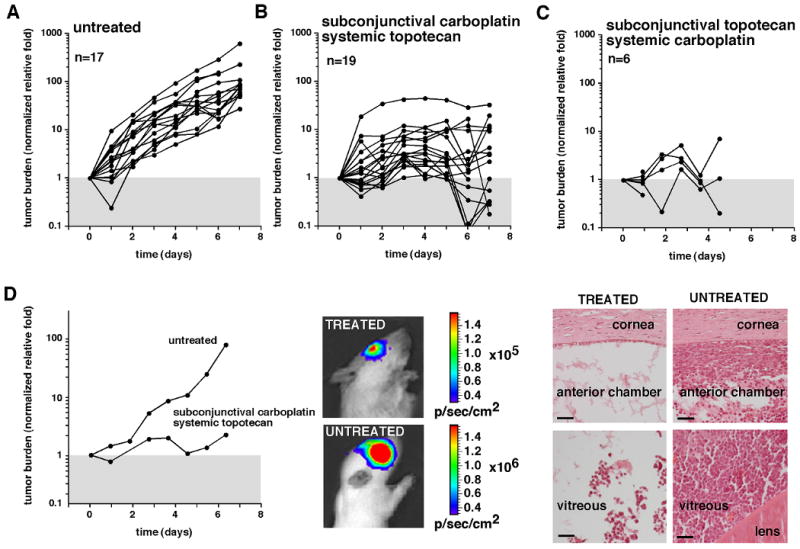

To test whether TPTsubcon/CBPsyst and CBPsubcon/TPTsyst elicit different tumor responses, we performed a tumor-response experiment using our rat xenograft model. The animals were randomly divided into 3 groups: saline, TPTsubcon (10 μg/eye)/CBPsyst (10 mg/kg), and CPBsubcon (100 μg/eye)/TPTsyst (0.2 mg/kg daily ×5). The dosage of drugs used in this study recapitulates those used in clinical trials as closely as possible, taking into account species-specific toxicity (calculations available upon request). In the saline-treated group, the tumor burden increased approximately 50 to 100 fold (Fig. 4A), and for the treated groups, it decreased approximately 10-fold reduction (p<0.01) compared to that of the saline-injected group after 7 days (Fig. 4B, C). Examples of an untreated rat and a treated (CBPsubcon/TPTsyst) rat with corresponding histopathology are shown (Fig. 4D). One of the most striking and surprising differences between the 2 groups was the morbidity associated with TPTsubcon/CBPsyst (Fig. 4C). In this group, no animals survived past Day 5 of chemotherapy.

Figure 4. Tumor response of subconjunctival topotecan combined with systemic carboplatin and subconjunctival carboplatin combined with systemic topotecan.

(A-C) The first group of rats with orthotopic xenografts (A) received saline injections; the second group (B) received CBPsubcon (100 μg/eye)/TPTsyst (0.2 mg/kg per daily ×5); and the third group (C) received TPTsubcon (10 μg/eye)/ CBPsyst (18 mg/kg). All data were normalized to the starting tumor burden to provide relative growth and response. (D) Bioluminescence measurements and histopathologic analysis of an untreated animal and an animal treated with CBPsubcon/TPTsyst. Scale bars, 25 μm.

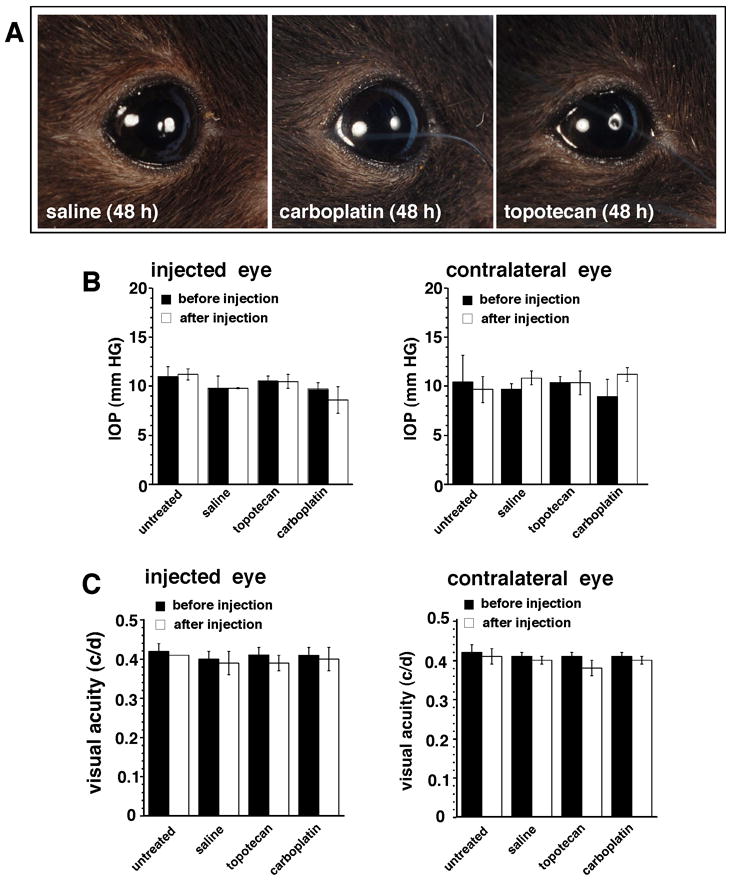

Ocular toxicity after subconjunctival injection of topotecan or carboplatin

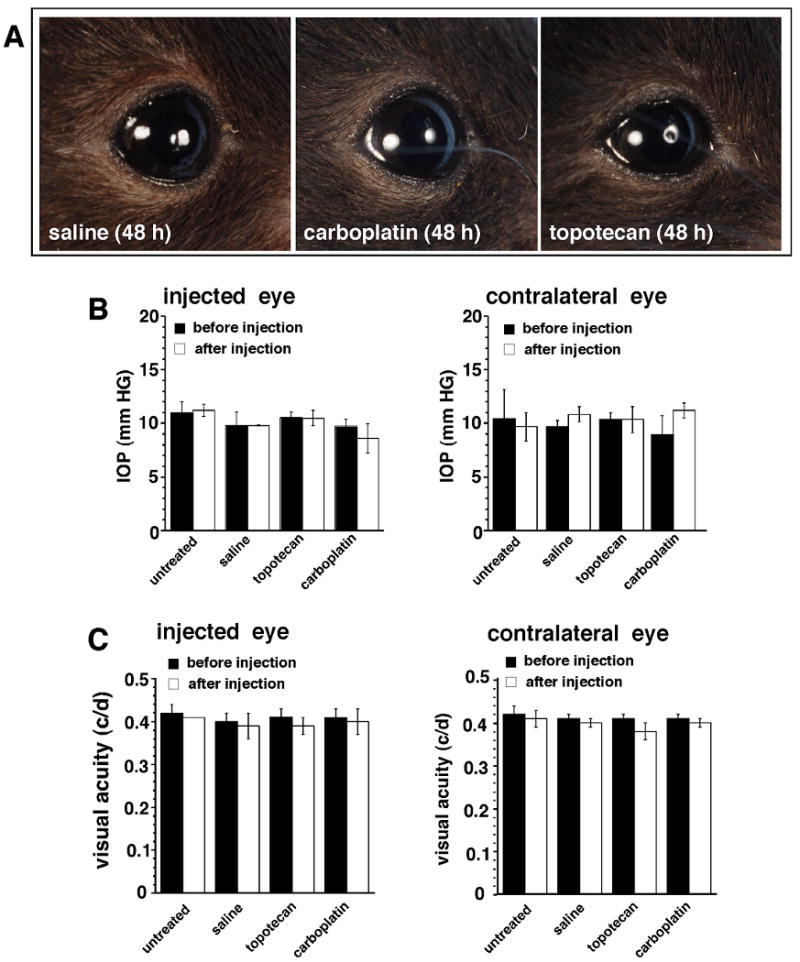

We randomly assigned 12 C57Bl/6 mice into 3 groups: untreated, salinesubcon (10 μL/eye), unilateral TPTsubcon (10 μg/eye), and unilateral CBPsubcon (100μg/eye) and assessed ocular toxicity (i.e., inflammation and other periocular side effects) 1, 3, and 7 days thereafter. No ocular toxicity was associated with any injection (Fig. 5A). We also monitored the animals for elevated IOP and impaired visual acuity but found no evidence of change in either measure at any time point (Fig. 5B, C).

Figure 5. Analysis of ocular effects of subconjunctival administration of chemotherapy.

(A) Photos of eyes of C57Bl/6 mice 48 h after subconjunctival injections of 10 μl saline, 100 μg CBP, or 10 μg TPT. (B) IOP was measured before and after administration of either drug. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of 6 measurements from 3 animals. (C) Changes in visual acuity as a result of subconjunctival chemotherapy injections were measured before and after injection in groups of 3 animals per treatment; the contralateral eye was used as a control. The data represent the mean and standard deviation of 2 measurements from the 3 animals in each group.

We then combined subconjunctival injections with systemic administration to determine if ocular toxicity was caused by exposure of the eye structures to the agents. Using 3 C57Bl/6 mice per group in 2 groups, we compared the ocular toxicity, visual acuity, and IOP in animals receiving TPTsubcon (10 μg/eye)/CBPsyst (18 mg/kg) or CBPsubcon (100 μg/eye)/ TPTsyst (0.1 mg/kg). After 1, 3, and 7 days, we found no difference in any measure in any group (data not shown). Histopathologic analysis confirmed no obvious changes occurred in the retinae, ciliary epithelia, or corneas of eyes exposed to CBPsubcon or TPTsubcon (data not shown).

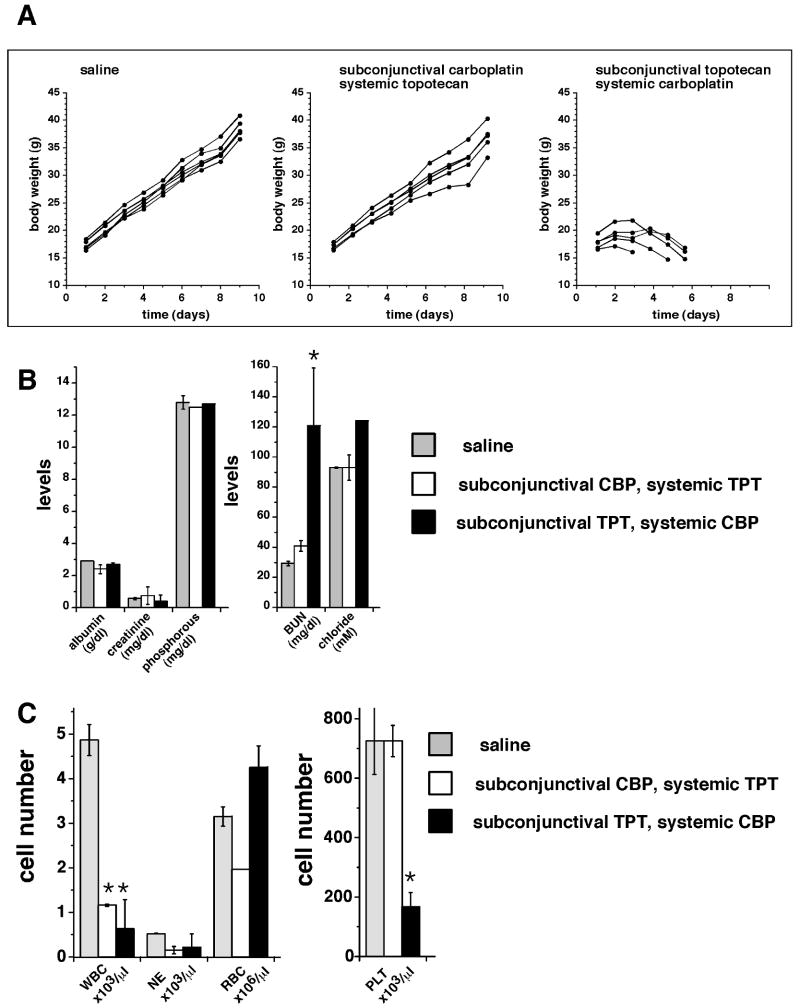

Myelosuppression and dehydration associated with subconjunctival topotecan and systemic carboplatin

We next examined drug-induced systemic toxicity. Using seven 8-day-old rats, we administered CBPsubcon (100μg)/TPTsyst (0.2 mg/kg daily ×5) to mimic the TPT dosage administered to children with retinoblastoma. Body weights were measured daily for 9 days and compared with those of untreated littermates; no significant weight loss was detected (Fig. 6A). Blood samples drawn on Days 0 and 10 showed no reduction in CBC-D measures after treatment (data not shown).

Figure 6. Side effects of topotecan and carboplatin combination chemotherapy using different routes of administration.

(A) The first group received saline injections; the second group received CBPsubcon (100 μg/eye)/TPTsyst (0.2 mg/kg daily ×5); and the third group received TPTsubcon (10 μg/eye)/ CBPsyst (10 mg/kg daily ×5). Body weights were measured each day for the subsequent 9 days. When TPTsubcon/CBPsyst was administered, all of the animals died with signs of dehydration by Day 6. (B) Blood chemistry results from treated and untreated juvenile rats. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of measures from 2 to 3 animals. (C) CBC-Ds from treated and untreated juvenile rats. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of data from 2 to 3 animals. Asterisks indicate statistical significance with p<0.05. Abbreviations: BUN, blood urea nitrogen; NE, neutrophils; PLT, platelets; RBC, red blood cells; WBC, white blood cells.

In a similar set of experiments with the delivery of agents reversed and at clinically relevant dosages, i.e., TPTsubcon (10 μg/eye)/CBPsyst (34 mg/kg), the juvenile rats could not tolerate the treatment (data not shown). When we reduced the CBP dose to 10 mg/kg, 3 of 6 animals survived to Day 6 of treatment but exhibited signs of profound dehydration (i.e., significant weight loss, lethargy, and tenting of the skin (Fig. 6A, data not shown). Blood chemistries obtained from the surviving rats on Day 6 were normal, except for an elevated BUN consistent with chemotherapy-related dehydration (Fig. 6B). In addition, CBC-D measures were consistent with myelosuppression, as evidenced by neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (Fig. 6C). These data show that TPTsubcon/CBPsyst is significantly more toxic than the reverse treatment delivery in juvenile rats.

Longitudinal study of systemic topotecan and subconjunctival carboplatin in a preclinical model of retinoblastoma

The orthotopic xenograft model is useful for short-term pilot studies, but for long-term studies, the genetic mouse model is preferred because it better recapitulates the human disease.7 To determine whether mice can tolerate CBPsubcon/TPTsyst at a clinically relevant dosage and whether this combination alters tumor progression, we performed a preclinical trial using Chx10-Cre;RbLox/Lox;p107−/−;p53Lox/Lox mice (Fig. 7A).7 If untreated, 95% (122/129) of the mice developed retinoblastoma, and 79% (97/122) developed bilateral disease (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. Longitudinal study of subconjunctival carboplatin and systemic topotecan administration in a genetic model of retinoblastoma.

(A) Chx10-Cre;RbLox/Lox;p107−/−;p53Lox/Lox mice develop aggressive and invasive retinoblastoma with 90% moribundity by the age of 250 days. Starting at 6 weeks of age, the animals were screened for tumors. Once the baseline tumor was established, their chemotherapy trial was initiated. Each course included a single dose of CBPsubcon (100 μg/eye) on Day 1 and TPTsyst (0.1 mg/kg) on Days 1 through 5 of the 21-day course. Around Days 20 to 21, CBC-D, visual acuity, and IOP were measured, and retinal images were acquired. (B) Representative data from an eye without detectable retinoblastoma and from an untreated eye with retinoblastoma prior to the study. If left untreated, tumors filled the vitreous, as visualized on ultrasound and MRIs. (C) Histogram of tumor response after 6 courses of CBPsubcon/TPTsyst in which 0.1 mg/kg topotecan was administered. When this combination included the clinically relevant AUC-guided dose of TPT (0.7 mg/kg), the response improved. Time to moribund status for treated animals was significantly longer (p <0.0001) than that of 8 untreated animals monitored in parallel. (D) Visual acuity in an untreated animal rapidly worsened as the tumor progressed. In treated eyes from 2 independent readings, vision was preserved for at least 189 days in 1 animal (A10-69) and restored after 130 days in another (A13-3). Abbreviations: CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Starting at 6 weeks of age, the mice were screened for retinoblastoma (Fig. 7A). Once a tumor was detected (Fig. 7B), baseline measurements were established for CBC-D, visual acuity, and IOP. Each animal then received six 3-week courses of chemotherapy (Fig. 7A) to recapitulate current retinoblastoma clinical protocols. On Day 1, each animal received CBPsubcon (100 μg) in the affected eye(s); on Days 1-5, each animal received TPTsyst (0.1 mg/kg). The animals then had 2 weeks off-therapy to complete the 3-week course. Tumors were monitored via digital retinal camera, ultrasound, and MRI (Fig. 7B), and IOP, visual acuity, and CBC-Ds were measured. If during treatment the tumor progressed in 1 eye but the other eye was favorable, surgical enucleation was performed. The animal then continued on the study per the predetermined schedule. Of the 42 eyes from the 22 animals in this study, 2 showed complete response; 11 had stable disease; and 29 showed disease progression (Fig. 7C, Table 3). The period required for 50% of the animals to reach moribund status, which was defined by imminent ocular rupture due to tumor filling the eye, increased from 60 days in untreated animals to 125 days in treated mice (Fig. 7C).

Table 3. Preclinical testing of CBPsubcon/TPTsyst in a genetic model of retinoblastoma.

| Animal # | Eye | Age (weeks) | Stage of disease | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A10-62 | R | 9 | 3 | SD | Normal visual acuity, IOP, CBC-D |

| A10-62 | L | 9 | 3 | SD | Normal visual acuity, IOP, CBC-D |

| A10-46 | R | 9 | 4 | PD | Elevated IOP |

| A10-46 | L | 9 | 2 | PD | Reduced visual acuity |

| A8-17 | R | 8 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A8-17 | L | 8 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A8-15 | R | 9 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A8-15 | L | 9 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A9-23 | R | 7 | 3 | PR | Normal visual acuity, IOP, CBC-D |

| A9-23 | L | 7 | 3 | PR | Normal visual acuity, IOP, CBC-D |

| A8-19 | R | 6 | 3 | PD | Reduced visual acuity |

| A8-19 | L | 6 | 3 | PD | Reduced visual acuity |

| A9-38 | R | 9 | 0 | PD | Elevated IOP, loss of vision |

| A9-38 | L | 9 | 2 | PD | Elevated IOP, loss of vision |

| A9-37 | R | 8 | 3 | PD | Elevated IOP, loss of vision |

| A9-37 | L | 8 | 3 | PD | Elevated IOP |

| A10-65 | R | 7 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A10-65 | L | 7 | 3 | SD | Reduced visual acuity |

| A10-63 | R | 7 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A10-63 | L | 7 | 2 | PR | Normal visual acuity, IOP, CBC-C |

| A10-69 | R | 9 | 0 | No tumor | |

| A10-69 | L | 9 | 3 | CR | Normal visual acuity, IOP, CBC-D |

| A13-5 | R | 9 | 3 | PD | Elevated IOP, loss of vision |

| A13-5 | L | 9 | 2 | PD | Elevated IOP, loss of vision |

| A10-67 | R | 7 | 3 | SD | Normal IOP |

| A10-67 | L | 7 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A13-3 | R | 9 | 3 | SD | Normal IOP |

| A13-3 | L | 9 | 3 | CR | Restoration of vision |

| A13-1 | R | 9 | 3 | PD | Elevated IOP, loss of vision |

| A13-1 | L | 9 | 2 | SD | Normal IOP |

| A11-75 | R | 6 | 0 | No tumor | |

| A11-75 | L | 6 | 2 | SD | Normal visual acuity, IOP |

| A8-11 | R | 8 | 3 | PD | Normal IOP, loss of vision |

| A8-11 | L | 8 | 2 | PD | Elevated IOP, loss of vision |

| A8-13 | R | 8 | 2 | CR | Normal visual acuity, IOP, CBC-D |

| A8-13 | L | 8 | 0 | PD | Normal visual acuity, IOP, CBC-D |

| A9-31 | R | 8 | 2 | PD | Enucleation |

| A9-31 | L | 8 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A8-3 | R | 8 | 0 | PD | Enucleation |

| A8-3 | L | 8 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A8-5 | R | 8 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A8-5 | L | 8 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A9-25 | R | 8 | 3 | PD | Enucleation |

| A9-25 | L | 8 | 4 | PD | Enucleation |

Abbreviations: CBC-D, complete blood cell count with differential; CR, complete response; IOP, intraocular pressure: PD, progressive disease; L, left; PR, partial response; R, right; SD, stable disease.

Next, we tested the higher, clinically relevant AUC-guided dose of 0.7 mg/kg TPTsyst on the same schedule in combination with CBPsubcon. We treated 44 animals (80 eyes) for 4 courses. To date, 43% (19/44) had a complete response and are long-term survivors (>270 days) (Fig. 7C). Both doses of TPT were associated with significant improvement of outcome (p<0.0001). Remarkably, vision was restored or preserved in 73% of the animals that showed complete response after CBPsubcon/TPTsyst (Fig. 7D).

Discussion

Retinoblastoma is unique among pediatric solid tumors, because locally delivered and systemically administered chemotherapy can be combined to optimize intraocular drug exposure, while minimizing the side effects associated with combination chemotherapy. We tested the feasibility, efficacy, and toxicity associated with this approach and found that the CBPsubcon/TPTsyst combination resulted in greater efficacy and fewer side effects in juvenile rats with orthotopic xenografts. No ocular side effects were detected after acute exposure or repeated dosing on a clinically relevant schedule. These findings were then validated in a longitudinal study of six 3-week courses administered to a knockout mouse model of retinoblastoma. For the first time, we ablated retinoblastoma in mice, and vision was restored in some long-term survivors. While these data show promise for stopping retinoblastoma in vivo in a genetic model of retinoblastoma, we still do not know if it will provide any predictive power for improved outcome for human retinoblastoma. Pharmacokinetic studies are essential for determining the vitreal exposure and the relative plasma exposure for a given dose. This is particularly important for the TPT/CBP combination, because if the systemic exposure of both drugs is too high, dose-limiting myelosuppression or other toxicities will develop. Our pharmacokinetic studies resulted in several key findings: (1) Subconjunctival delivery of either agent efficiently penetrated the eye, as indicated by the vitreal concentration of drugs; however, (2) the AUCvitreous/AUCplasma ratios indicated that the intraocular penetration of TPT was better than that of CBP. (3) The presence of tumor in the eye slightly increased the penetration of both drugs. (4) Subconjunctival administration led to greater vitreal exposure than systemic administration of either drug. (5) Following unilateral subconjunctival injection, the contralateral eye showed detectable vitreal exposure to the drug, as a result of its uptake into the circulation. These data indicate that subconjunctival delivery of either drug is feasible for the treatment of retinoblastoma. Visual acuity, IOP, and cytotoxicity analyses showed no detectable ocular toxicity associated with subconjunctival injection of either drug. In addition, when combined with systemic exposure to the other drug, no changes in ocular physiology or histology were observed.

In contrast, chemotherapy-related dehydration and myelosuppression were major challenges in these studies when clinically relevant dosage of TPTsubcon/CPBsyst (TPT, 10 μg/eye; CBP, 34 mg/kg) was administered. Even when the CBP dose was reduced to 10 mg/kg, the animals showed signs of severe dehydration and myelosuppression. This was surprising, because no detectable toxicity or side effects were observed when the delivery methods were reversed, despite similar tumor response. We speculate that this was due to the increased overall exposure of the two agents with this route of delivery because of the large dose of CBP that is used for systemic administration. The important advantage of the CBPsubcon/TPTsyst combination is that TPT can be delivered on the daily ×5 schedule used clinically. This approach provides continued chemotherapeutic exposure for several days; this is not possible when the methods of delivery are reversed, because TPTsubcon is administered only on Day 1 of therapy.

Toxicity data from our orthotopic xenograft model confirmed that the preferred drug delivery is CBPsubcon/TPTsyst. Tumor response to TPTsubcon/CBPsyst beyond 5 days could not be monitored in the rats due to morbidity. The advantage of this model is that it is well-characterized and standardized, and direct comparisons can be made with previous studies of retinoblastoma;4 the disadvantage is that only short-term studies can be conducted because the tumors grow quickly. Thus, we combined preliminary studies in this model with long-term studies in our genetic mouse model.

We validated the feasibility of multiple 3-week courses of CBPsubcon/TPTsyst to treat retinoblastoma by using the Chx10-Cre;RbLox/Lox;p107−/−;p53Lox/Lox mouse model. The animals received a comparable dose on the same schedule as that used to treat patients with retinoblastoma. CBC-D measures were closely monitored, and the mice recovered well on the treatment regimen. Tumor response was observed in a substantial proportion of the animals, as measured by reduced tumor burden, recovery of vision, maintenance of normal IOP, and long-term survival (up to 1 year). At a subclinical dose of TPT (0.1 mg/kg), the animals fared better than untreated animals, but only at the clinically relevant, AUC-guided dose (0.7 mg/kg) was long-term survival and restoration of vision achieved. Periocular carboplatin can cause significant scar tissue in children with retinoblastoma. In our studies we did not observe any scar tissue in the mice but this remains a significant challenge for subconjunctival delivery in patients. It may be possible to develop an alternative delivery device to direct drug across the sclera without exposure to the sobconjunctival tissue.

One important difference between our study and clinical treatment of retinoblastoma is that children with retinoblastoma also receive focal therapies such as laser therapy. We propose that mice can tolerate CBPsubcon (≤20 mg/eye) combined with TPTsyst (0.7 mg/kg) for six 3-week courses using doses that are comparable to those previously used to treat patients with retinoblastoma. More importantly, these data establish the feasibility of conducting preclinical drug studies in genetic and orthotopic xenograft animal models of retinoblastoma.

Acknowledgments

The St. Jude Animal Imaging Center contributed to the imaging studies and surgeries. M.A.D. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Investigator.

Support: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Cancer Center Support CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute, and grants from the American Cancer Society, Research to Prevent Blindness, Pearle Vision Foundation, International Retinal Research Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trust, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: none.

References

- 1.Ries LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al. Cancer Incidence and Survival among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. Bethesda, MD: 1999. NIH Pub. No. 99-4649. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyer MA, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Wilson MW. Use of preclinical models to improve treatment of retinoblastoma. PLoS Med. 2005;2(10):e332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurie NA, Donovan SL, Shih CS, et al. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature. 2006;444(7115):61–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurie NA, Gray JK, Zhang J, et al. Topotecan combination chemotherapy in two new rodent models of retinoblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(20):7569–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Athale UH, Stewart C, Kuttesch JF, et al. Phase I study of combination topotecan and carboplatin in pediatric solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(1):88–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abramson DH, Frank CM, Dunkle IJ. A phase I/II study of subconjunctival carboplatin for intraocular retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1947–50. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90406-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Schweers B, Dyer MA. The first knockout mouse model of retinoblastoma. Cell Cycle. 2004;3(7):952–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFall RC, Sery TW, Makadon M. Characterization of a new continuous cell line derived from a human retinoblastoma. Cancer Res. 1977;37(4):1003–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shih CS, Laurie N, Holzmacher J, et al. AAV-mediated local delivery of interferon-β for the treatment of retinoblastoma in preclinical models. Neuromolecular Medicine. 2009;11(1):43–52. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8059-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson J, George EO, Poquette CA, et al. Synergy of topotecan in combination with vincristine for treatment of pediatric solid tumor xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(11):3617–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Argenio DZ, Schumitzky A. ADAPT II User's Guide: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Systems Analysis Software. Los Angeles: Biomedical Simulations Resource; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prusky GT, Alam NM, Beekman S, Douglas RM. Rapid quantification of adult and developing mouse spatial vision using a virtual optomotor system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(12):4611–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chantada GL, Fandino AC, Carcaboso AM, et al. A phase I study of periocular topotecan in children with intraocular retinoblastoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(4):1492–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]