Abstract

Bacterial luciferase contains an extended 29-residue mobile loop. Movements of this loop are governed by binding of either flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2) or polyvalent anions. To understand this process, loop dynamics were investigated using replica-exchange molecular dynamics that yielded conformational ensembles in either the presence or absence of FMNH2. The resulting data were analyzed using clustering and network analysis. We observed the closed conformations that are visited only in the simulations with the ligand. Yet the mobile loop is intrinsically flexible, and FMNH2 binding modifies the relative populations of conformations. This model provides unique information regarding the function of a crystallographically disordered segment of the loop near the binding site. Structures at or near the fringe of this network were compatible with flavin binding or release. Finally, we demonstrate that the crystallographically observed conformation of the mobile loop bound to oxidized flavin was influenced by crystal packing. Thus, our study has revealed what we believe are novel conformations of the mobile loop and additional context for experimentally determined structures.

Introduction

Light emission of biological origin has fascinated mankind for centuries (1). Luciferase, the enzyme responsible for light emission in bioluminescent bacteria, catalyzes the reaction of reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2), O2, and an aliphatic aldehyde to yield FMN, the corresponding carboxylic acid, and blue-green light. Structurally, luciferase is composed of two homologous subunits designated α and β, both of which assume the TIM barrel fold (4,5). Although the β-subunit is required for activity, the catalytic site resides exclusively on the α-subunit (6–8). The most substantial compositional difference between subunits corresponds to a highly conserved stretch of residues between positions 260 and 290 unique to the α chains of luminous bacteria (9).

In the crystal structures of the ligand-free enzyme, a portion of the α-subunit consisting, approximately, of residues 262–291 is disordered (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 1LUC) (4,5). This segment of the protein corresponds to a protease-labile mobile loop (10,11). Proteolytic cleavage of the loop results in enzymatic inactivation. However, binding of either FMN or polyvalent anions protects the enzyme from proteolysis (10,12). The mobile loop has been the subject of several mutagenesis studies (13–15). In an earlier report, the entire mobile loop was genetically removed, resulting in loss of ∼8% of the luxA gene (14). The tertiary structure, ability to generate the chemical products, substrate affinities, and the color of luminescence are unaltered in the deletion mutant. However, the total quantum yield is reduced two orders of magnitude. It has been proposed that the source of this reduction is an inability to stabilize reaction intermediates (14). Mutagenesis data support the hypothesis that the mobile loop is responsible for a lid-gating mechanism similar to other TIM-barrel enzymes (13).

In the luciferase/FMN complex, the asymmetric unit contained two β/α-heterodimers (PDB ID 3FGC) (8). One of the nonsymmetry-related heterodimers bound to FMN (the flavin product of the reaction) after soaking and the other did not. Comparison of the two active sites revealed intriguing differences. Two unique conformations of the mobile loop corresponding to each of the α-subunits were observed. These represent the first case, to our knowledge, where the majority of the mobile loop is resolved. The primary difference between conformations corresponds to a secondary structural element composed of two antiparallel β-strands near the interface with the β-subunit found exclusively in the flavin-free α-subunit. Unfortunately, the missing segments (corresponding to residues 283–290) are directly adjacent to the flavin-binding cavity. The authors suggested that the conformational differences in the observed portion of the loops were due to crystal packing, but they failed to address the question of whether FMN binding was impacted.

Modeling of large loop movements in proteins remains a challenge due to limitations in the efficacy of sampling the free-energy landscape (16). A common approach to monitor slow events such as protein folding has been the use of replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) (17–19). An approximation upon this technique is replacement of explicit solvent molecules with continuum solvent representations to reduce viscosity and allow for accurate representation of sizeable displacements on computationally tractable timescales (20,21). This methodology yields thousands of structures, necessitating tools for representing the diversity and relative significance of members within a structural ensemble. To describe libraries of structurally similar conformations of the mobile loop, we used a bipartite approach consisting of clustering and network analysis. Graphical network representation, which allows for visualization of topological relationships between clusters of conformations that cannot easily be seen by classical clustering algorithms, is an increasingly common approach to depicting protein structure, folding, and dynamics (22,23–25).

Method

Structure preparation

We began our simulations using the coordinates of heterodimer 2 in the luciferase/FMN complex (PDB ID 3FGC) (8). The mobile loop from heterodimer 2 had stronger electron density with the higher degree of experimental precision. For computational efficiency, only the α-chain was included in the simulations. The residues between positions 283 and 291 not observed in the crystal structure were added using homology-based loop modeling (26). Simulations were conducted in the presence and absence of FMNH2. The position of FMNH2 was determined based on the location of FMN experimentally observed in heterodimer 1 by superimposing two heterodimers. The movements of residues within the subunit interface were weakly constrained using harmonic potential to prevent complete unfolding of the α-subunit over the course of simulation. No constraints were applied to the FMNH2 or the mobile loop.

REMD simulations

The most significant challenge during these simulations was the accurate simulation of the 29-residue mobile loop capable of large-scale movements. Such displacements are inherently slow, necessitating techniques to enhance sampling of the available conformational space in a computationally tractable time-frame. Preliminary attempts to simulate conformational fluctuations using traditional molecular dynamics failed due to stalling in local free-energy minima. Multiple independent simulations (n = 6) were conducted in either explicit or implicit solvent for ∼20 ns. The mobile loop adopted a single, seemingly random, fixed position during equilibration and remained fixed throughout the simulation. Thus, we employed REMD simulation with a generalized Born (GB) model to obtain better sampling of loop conformations.

In GB models, solvent molecules are represented using a continuous implicit solvation (20,27). The second consequence of the use of implicit solvation is a substantial reduction in the friction of the system. Therefore, the protein is able to move at a much faster rate (27). This complicates the interpretation of data obtained from simulations in any kinetic sense. In addition, several groups have reported that GB model overstabilizes ionic interactions (28,29). However, within those limitations, GB models have proven to be a powerful tool to study protein conformations (30,31). As a test of the validity of our sampling method, we repeated our simulations using a different GB implicit solvent model. Comparison of loop models for the closed complex from either solvent model reveals striking similarities (see the Supporting Material). We conclude that the model of the closed complex yielded by our method is recapitulated by multiple solvent models.

REMD differs from standard MD in the parallel nature of simulation (18). Instead of a single simulation at a single temperature, multiple parallel simulations are conducted over a wide range of temperatures. Periodically, conformations of simulation replicas running at different temperatures are exchanged according to a Monte Carlo procedure. As a result, the conformational space sampled over the simulation is substantially increased. Due to the extremely large displacements involved in a 29-residue mobile loop, this approach was necessary to achieve spontaneous opening and closing of the mobile loop.

Parameter files for the protein were generated using AMBER99SB (32). For the flavin, charge parameters were obtained using Gaussian 03 HF/6-31G∗ and RESP (33,34). Force constants for bonds, angles, and torsions of the flavin were taken from the GAFF parameter set (35). Parameters for the phosphate group of FMNH2, initially obtained from GAFF, displayed significant instabilities, similar to those described in a previous report by Homeyer et al. (36). These instabilities resulted in an inability to continue the simulation beyond a brief period of energy minimization. Therefore, following the methods of Homeyer et al., bond and angle force constants for the phosphate groups were adopted form AMBER99 (20).

REMD simulations were executed using the AMBER10 program (37). Our primary goal was to effectively explore conformations the mobile loop can take, an approach similar to that of Yadak et al. (19). Sixteen replicas at temperatures distributed between 280 and 340 K were simulated. The temperature was chosen to be near room temperature to avoid unfolding (19). Exchanges between different temperatures were attempted every picosecond. The cutoff distance for electrostatic interactions was 16 Å. The temperature of the system was controlled using Langevin dynamics with a collision frequency (γ) of 1 ps. Bond vibrations between any atom bound to hydrogen were constrained by the SHAKE algorithm (38). OBC model II was used for the GB model parameter set (20). The additional simulation parameters were taken from the default SANDER settings (37). Three independent simulations of 3 ns each were performed with and without FMNH2, totaling 9 ns for each state. The convergence of the data was examined using network analysis (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). A dataset consisting of 1000 structures was gathered from equal numbers of structures from the replica trajectories at 280 K and 300 K conducted with and without FMNH2. We examined the structures from those two temperatures to sample low-energy closed conformations and to examine the extent of flexibility of the mobile loops for opening (Fig. S2). It should be noted that the aim of this calculation is to obtain high-quality models of loop flexibility using REMD and the AMBER force field. Obtaining a precise free-energy profile of the loop conformation would be difficult due to the size of the system, especially for the open conformations, and is beyond the scope of this study.

Network analysis of loop conformational ensemble

Network representations and clustering were used to analyze the conformational ensemble of the mobile loop. Network constructions were based on the backbone root mean-squared deviation (RMSD) pairwise matrix. To calculate the RMSD between mobile loops, structures were aligned with the exclusion of the mobile loop (residues 260–290). RMSD values were then computed based on the position of backbone atoms of the mobile loop without realignment.

To visualize the diversity of the structural ensemble, we employed network analysis. A network representation of ensemble configurations is helpful for visualizing the topology of the conformational space in a way that cannot be easily done with clustering analysis. The most effective way to use network constructions is to 1), reveal clusters and their content; and 2), establish connections between clusters. We discussed the detail of the procedure in a previous article (22), and here briefly describe the process. Cytoscape was used to generate network graphs depicting the diversity of loop RMSD values (39). In these graphs, nodes represent structures of the mobile loop and the links or edges between the nodes represent similarity below a cutoff RMSD value. The links are established using a cutoff of 2.75 Å applied to the matrix of RMSD values between all combinations of nodes. To determine the conformation of the mobile loop sampled in the presence and absence of FMNH2, the concatenated ensemble of structures was represented as a network. To visually indicate the difference between two ensembles, the nodes from each ensemble were distinguished by color. We should note that the node connectivity in the network graph is merely a structural similarity and not necessarily the real transition event in the simulation. Kinetics information cannot be extracted from the network analysis we conducted here. For such purposes, microscopic rates and network connectivity need to be analyzed further (40).

Although we used network analysis as a primary tool to study the dynamics of the mobile loop, we also performed traditional clustering analysis. Clustering is better suited to identify the members of the clusters and, in particular, the centroid of a cluster. Similar conformations were grouped according to a k-means clustering algorithm (41). The goal of clustering was to identify a common conformation unique to the simulation conducted in the presence of FMNH2. The structure of the closed conformation obtained from the k-means clustered network was included in the network. In a similar way, representative structures from the other four well-populated clusters were also added to the graph.

Structural definitions

The nomenclature used for the mobile loop in this manuscript designated the flavin proximal region as residues 280–290 and the flavin distal portion of the loop as residues 260–279.

Results

Analysis of global dynamics

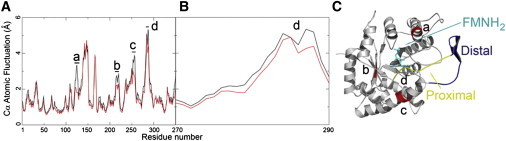

To characterize residue-specific atomic fluctuation during the course of MD simulation, the RMS fluctuation of each residue was calculated. The single region with the greatest flexibility was the mobile loop (Fig. 1). This trend recapitulates data from crystallographic experiments where the mobile loop lacks unambiguous electron density (4,5). Flexibility is also observed in a region adjacent to the mobile loop and locations associated with the anion binding site.

Figure 1.

(A) Atomic fluctuations measured at the α carbon for flavin-free (black) and flavin-bound (red) luciferase are shown. Sites of significant change in mobility are labeled with lower case letters a–d. (B) Changes in mobility in the mobile loop between residues 270 and 290. (C) Corresponding regions on luciferase where mobility differs (red). The location of the flavin is shown in cyan with sticks. The flavin-proximal segment of the mobile loop (residues 280–290), another site where mobility differs, is shown in yellow. The flavin-distal segment of the mobile loop (residues 260–279) is shown in blue.

To ascertain the effect of FMNH2 binding on protein structure, atomic fluctuations were computed for both simulations (Fig. 1 A). In general, the presence of FMNH2 reduced the mobility of luciferase at four separate locations (Fig. 1 A, a–d) associated with the anion-binding site (Fig. 1 A, a) (42), the aldehyde-binding site (based on mutagenesis) (Fig. 1 A, b and c) (43,44), and the segment of the mobile loop between residues 280 and 290 (Fig. 1 A, d). The mobile loop consists of two segments: the flavin-distal region (resides 260–279) and the flavin-proximal segment of the mobile loop (residues 280–290). In general, the flavin-proximal region is more flexible than the flavin-distal region. However, in the presence of FMNH2, the mobility of residues within the flavin-proximal segment is substantially reduced. This change in dynamics is due to contacts between the flavin-proximal portion of the loop and FMNH2 or the surface of the enzyme near the active site. Further analysis indicates that changes in mobility of the flavin-proximal portion of the loop were the result of interactions between residues R290 and E175 or between those residues and FMNH2 (discussed in detail later).

Clustering and network analysis of the conformational ensemble

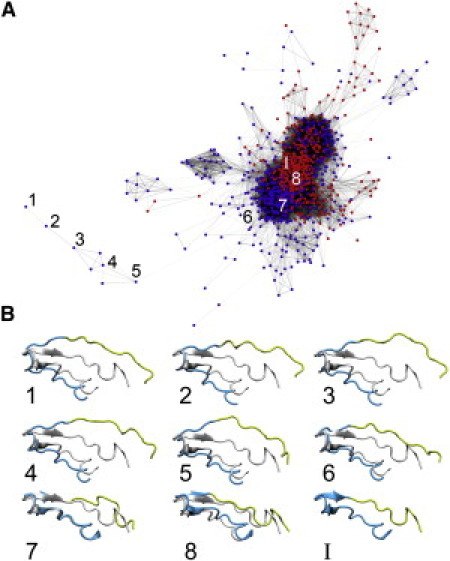

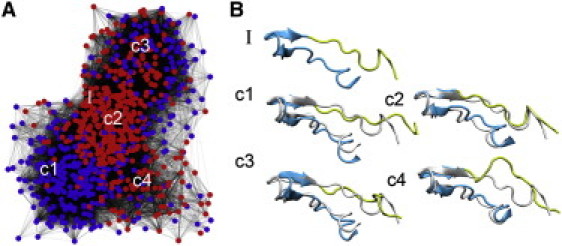

Despite the existence of four crystallographic models of the luciferase β/α heterodimer, a complete model of the active-center mobile loop has not been described. To determine this structure, the distribution of conformational space sampled during the simulation was examined using a network. In this graph, structures were represented as nodes and structural similarity of the mobile loop by node connectivity (Figs. 2 and 3). Fig. 2 illustrates a graph of the loop conformational ensemble obtained from REMD simulations. The network is composed of both a dense core and a sparse fringe region. The majority of the sampled conformation belongs to the core region, which we discuss first (Fig. 3). The same network representation was used to examine the convergence of the samples and the effect of temperature on them (Fig. S1 and Fig. S2).

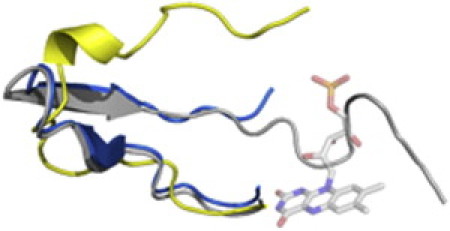

Figure 2.

Network analysis of loop opening and closure. This network contains each structure from the simulation conducted in the presence (red) or absence (purple) of ligand. Each node represents a single structure from 1000 structures taken equally from each simulation. Connections indicate close structural relatedness within 2.75 Å. The structure with the greatest distance to the closed complex in this network is labeled with the number one. A trajectory between this structure and the closed complex was devised to minimize the number of hops (1–8). Structures at hop sites are shown against the closed complex below and include the flavin-proximal segment (yellow, residues 280–290) and a region containing the flavin-distal segment (blue, residues 260–279).

Figure 3.

(A) Core portion of structures obtained from REMD. Nodes corresponding to structures obtained from simulations conducted in the presence of ligand are shown in red, whereas those obtained from simulations in the absence of ligand are shown in blue. Connections indicate structural relatedness within 2.75 Å. (B) Representative structures from the four major clusters are labeled c1–c4. Cartoons of representative conformations from the four clusters are shown relative to the closed complex (gray), with the proximal segment (residues 280–290) in yellow and a region containing the distal segment (residues 260–279) in blue. The closed complex is also shown without structural superposition (I).

Models of loop closure

Based upon the graphs of these networks, there are distinct groups of nodes within the core. The representative structures from each of the major clusters are included in the network (Fig. 3 A, c1–c4). Half of the nodes represent the loop conformation obtained from REMD with FMNH2 and the other half that obtained without FMNH2. Comparison of the distributions of those two classes of structure provides insight into the effect of FMNH2 on the conformation of the mobile loop. It is interesting to note that of the four major clusters, one appears specific to the simulations conducted in the presence of FMNH2 (Fig. 3, c2), and one is unique to simulations in the absence of FMNH2 (Fig. 3, c1). These two structures differ very slightly in the conformation of the proximal portion of the mobile loop due to the presence of the FMNH2. The other two major conformations were sampled regardless of the presence or absence of FMNH2 (Fig. 3, c3 and c4). Thus, it appears that the mobile loop is intrinsically flexible and FMNH2 binding modifies the relative population of conformations.

A single well-populated cluster (Fig. 3, c2) contained structures exclusively collected from the simulation conducted in the presence of FMNH2 (Fig. S3). We defined the centroid conformation of this cluster as a representative model of the closed conformation (Fig. 4; for more details, see Fig. S4).

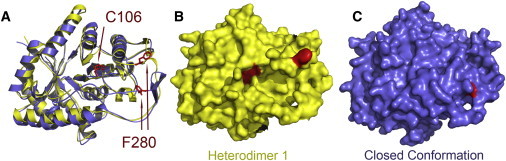

Figure 4.

Exposure of F280 and C106 to solvent in the model of the closed complex compared to the crystal structure of luciferase bound to FMN. (A) Overlay of the closed complex (blue) and chain A from 3FGC.pdb (yellow) (8). The location of C106 is essentially identical, whereas the position of F280 is substantially different. (B) The surface of chain A from 3FGC.pdb is shown without rendering oxidized flavin (8). The surfaces of C106 and F280 are clearly visible (red). (C) The surface of the closed complex is shown without rendering reduced flavin. Only the backbone of F280 can be seen on the surface (red).

To describe the distribution of the closed conformation throughout the ensemble, the RMSD for each structure was computed relative to the closed conformation (Fig. S5). Approximately one-third of structures visited during the simulation containing FMNH2 are strikingly similar to the bound conformation (RMSD <3.5 Å), whereas structures from the simulation conducted in the absence of FMNH2 are in the same range much less frequently. This suggests that the mobile loop spontaneously and reversibly adopts a closed conformation in the presence of FMNH2. In this conformation, the flavin-distal portion of the mobile loop maintains the pair of antiparallel β-strands. The flavin-proximal segment adopts a compact structure against the surface of the enzyme. The lid function of the mobile loop appears to be the result of loop-surface contacts such as the salt link between R290 and E175 (R/NH2-E/OE1, 2.7 Å) near the flavin binding site and the hydrogen bond between the backbone carbonyl of residue T288 and the phenolic hydroxyl group of Y110 (TO-YOH, 2.05 Å) (Fig. S6).

A model for loop opening

The second purpose of the network analysis was to identify loop conformations with maximal structural deviation from the closed complex. These states may represent permissible structures for the movement of small molecules into or out of the active site. Most of the structures observed in the simulation reside in the core of the network and differ only slightly from each other in the flavin-proximal region. Along the fringes of the network, dissolution of the β-strands within the distal segment was observed. However, the proximal segment remained near the surface of the enzyme. A fully open loop conformation was detected based on the largest deviation from the closed structure (Fig. 2, I). The nearest structural relatives to these nodes all appear to contain changes in the proximal portion of the mobile loop.

Although our simulation does not address the relative timescale of dynamic motions, the relative displacements between the closed and fully open conformations of the mobile loop are substantial. Large displacements in proteins, such as loop closure and domain motions, often require millisecond timescales. Using stopped-flow kinetics, it has been reported that upon binding FMNH2, luciferase undergoes a slow event believed to be a conformational change before reaction with oxygen (45). Based on the differences we observe in the open versus the closed conformation, we suggest that the kinetically slow conformational change may correspond to movements in the mobile loop (4,5,8,46).

Discussion

Model of closed conformation and previous experimental data

Three experimental findings support our model for the closed conformation of bacterial luciferase. First, in the model we propose for the closed complex, F280 is buried but close to the surface of the protein, near the antiparallel β-strands in the distal portion of the loop (Fig. 4). In the presence of polyvalent anions or FMN, luciferase undergoes a conformational change, reducing the protease sensitivity of the mobile loop (10–12,47). Limited proteolysis of luciferase results in enzymatic inactivation, but the quaternary structure of the protein remains intact (11,48). In the case of digestion with chymotrypsin, the initial site of cleavage within the α-subunit has been localized to residue F280 (9). In the closed complex we report, the phenyl group of F280 is inaccessible to solvent.

In the model we report for the bound (closed) conformation, the proximal region of the mobile loop encapsulates the active-center cavity (Fig. 4). In the absence of reactants or polyvalent anions, treatment of luciferase with alkylation reagents, such as N-alkyl-maleimides, results in modification of the reactive thiol at position C106 of the α-subunit concurrent with enzymatic inactivation (6). Binding of FMN or aldehyde protected the thiol from alkylation, suggesting that the reactive thiol must reside in or near the substrate-binding cavity. In addition, after reaction of luciferase with FMNH2, aldehyde, and oxygen, the flavin was chromatographically separated from the enzyme at low temperature (50), and enzyme purified by this method was partially resistant to inactivation by proteolysis and modification by alkylation of the reactive thiol (50). Our model is consistent with these data, as the conformation of the flavin-proximal region of the mobile loop in the closed conformation would sterically hinder entry of the alkylation agents into the active-center cavity (Fig. 4).

Finally, the model presented for the closed complex contains a pair of antiparallel β-strands in the distal segment of the mobile loop. Binding of phosphate induces conformational changes in luciferase from Vibrio harveyi, Photobacterium phosphoreum, and Vibrio fischeri, and near-ultraviolet CD spectroscopy suggested that the overall β-strand content displayed a small but significant increase of ∼5% (47). This result implies that the proteolytically insensitive conformation induced by FMN or phosphate binding contains either longer stretches of β-strands or novel β-strands. Sparks and Baldwin also noted that upon deletion of the luciferase mobile loop, in phosphate buffer, the β-strand content of the deletion mutant was 5–10% less than that of the wild-type enzyme (14). We suggest that strand formation in the distal segment of the loop is diagnostic of flavin binding in the active center.

Comparison to crystallographic data

The closed conformation of the mobile loop was compared to both structures observed in the luciferase/FMN complex based on the RMSD of the backbone (Fig. 5) (8). The closed conformation of the mobile loop, containing the β-strands in the flavin-distal portion of the loop, is remarkably similar to the conformation observed in heterodimer 2 of the crystal structure (the flavin-proximal region is not determined). The closed form has little resemblance to the mobile loop of heterodimer 1. Initially, this result was surprising, because strong electron density for FMN was observed exclusively in heterodimer 1. Put another way, the mobile loop appears to be in a closed conformation in the absence of substrate and semiopen when bound to the flavin product, FMN.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the structure of the mobile loop from the closed complex (gray) to heterodimer 1 (yellow,backbone RMSD of 6.8 Å) and heterodimer 2 (blue, backbone RMSD of 2.2 Å) from 3FGC.pdb (8).

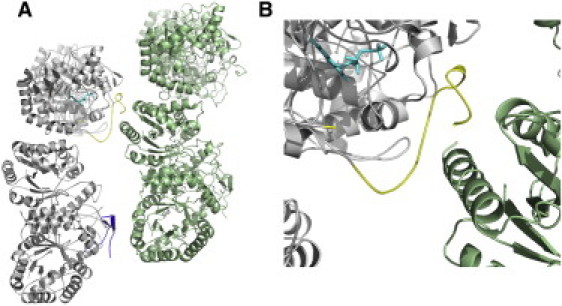

This apparent discrepancy can be explained by the experimental procedure. Because the heterodimers were arranged in different orientations within the crystal lattice, packing interactions may account for the difference in FMN binding. This possibility was examined by generating symmetry-related asymmetric units (Fig. 6). It is apparent that there are packing interactions between both mobile loop conformations and the neighboring protein molecules within the crystal. These interactions appear to be more extensive for heterodimer 1 where a helix runs between the two halves of the distal segment of the mobile loop. This packing arrangement may have locked the mobile loop into an open conformation. If the considerably fewer interactions between neighboring protein molecules and heterodimer 2 do not interfere with loop dynamics, the expectation would be that in the presence of polyvalent anions, a closed conformation would predominate when FMN is bound.

Figure 6.

Packing of the mobile loop from 3FGC.pdb. (A) Two adjacent symmetry-related pairs of the asymmetric unit are shown in gray and green. The observed portion of the mobile loop from heterodimer 2 is shown in blue. The mobile loop from heterodimer 1 is shown in yellow. FMN is depicted in sticks and shaded in cyan. (B) Note the helix from the symmetry-related protein molecule within the distal portion of the mobile loop from heterodimer 1.

Before collecting diffraction data, luciferase was first crystallized and then FMN was soaked into the crystal (8). The structure of the mobile loop in heterodimer 2 suggests that the conformation of the distal portion of the loop is either closed or semiclosed. Therefore, the disordered proximal portion of the loop may have sterically hindered entry of flavin into the active site during the brief period of soaking. FMN binds to the heterodimers 1 with open mobile loop, which allows entry of the FMN, and it remains open due to crystal packing despite the natural tendency for luciferase to spontaneously adopt a closed conformation in the presence of polyvalent anions. It is important to note that both the open and closed forms of the mobile loop observed in the luciferase/FMN structure exist in the absence of flavin. In unpublished work, our group has obtained crystals in the absence of flavin in the same space group as the structure containing flavin (8). The conformation of the mobile loops remains the same, possibly due to the packing interactions discussed above. Results of this study confirm the fact that interpretation of x-ray structures to infer protein functional dynamics needs to be done carefully.

Conclusion

Bacterial luciferase contains a mobile loop postulated to be responsible for partitioning solvent from the active center during catalysis (8,14). Due to intrinsic mobility, x-ray diffraction experiments have yet to provide a complete structure of the loop. We employed computational techniques to address this problem. These simulations remain technically challenging due to the computational difficulty of simulating extended loops. Therefore, we used an implicit solvent model with REMD to enhance the sampling. Our approach yielded a vast number of sampled conformations. Consequently, to deconstruct this complex dataset, network representations and clustering were used to characterize loop conformations visited during the simulations.

We address three outstanding questions in this study. First, the structure of the mobile loop upon binding FMNH2 was unknown before this work. Multiple features of the closed conformation are consistent with prior experimental results including inaccessibility of F280 to proteolysis, secondary structural content, occlusion of the reactive thiol, and the large displacement required to assume the fully open conformation (45,47,49,50). In lieu of crystallographic evidence for the enzyme-FMNH2 complex, the model described here will assist in additional investigations into bacterial bioluminescence.

Second, description of the conformational space available to flavin-free luciferase is challenging. The open conformation is rare during these simulations, as the predominant form of the enzyme is in either a closed (simulations in the presence of FMNH2) or semiclosed state. Thus, the open conformation is not a single conformation but an ensemble, as a number of proximal loop conformations did not sterically occlude the active center. Many somewhat dissimilar structures allow for the products to diffuse out of the active center. The proposed model of the fully open conformation allows for estimation of a maximal displacement. These coordinates provide a hypothesis for solution experiments using either fluorescent tags or spin labels to experimentally describe the difference between the bound and unbound conformations of the mobile loop.

Third, despite substantial effort, a precise description of the effects of anion binding upon luciferase structure and function is elusive. In a previous model of luciferase bound to flavin, Meighen and co-workers examined the likely position of the anion binding site (51). Based on the low-resolution crystal structure and the length requirements of the ribitol moiety of the flavin, it was postulated that the anion site included the amide of E175 and the guanidinium group of R107 (4,51). These components are included in the model we describe here, as is the guanidinium of R125 (Fig S6).

In conclusion, using molecular dynamics simulations we have described key mobile loop conformations that have thus far been experimentally elusive. Our models are supported by decades of experimental studies on the kinetic mechanism of this well-studied enzyme. Moreover, our simulations have yielded insights into rare conformations sampled by the mobile loop that x-ray crystallography cannot directly provide.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. Miriam Ziegler for her gracious editorial contributions.

This study was supported by the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and the College of Science of the University of Arizona and by the College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences of the University of California, Riverside.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Boyle R. Some observations about shining flesh, both of veal and of pullet. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1672;7:5108–5116. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reference deleted in proof.

- 3.Reference deleted in proof.

- 4.Fisher A.J., Raushel F.M., Rayment I. Three-dimensional structure of bacterial luciferase from Vibrio harveyi at 2.4 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6581–6586. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher A.J., Thompson T.B., Rayment I. The 1.5-Å resolution crystal structure of bacterial luciferase in low salt conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:21956–21968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicoli M.Z., Meighen E.A., Hastings J.W. Bacterial luciferase. Chemistry of the reactive sulfhydryl. J. Biol. Chem. 1974;249:2385–2392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cline T.W., Hastings J.W. Mutationally altered bacterial luciferase. Implications for subunit functions. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3359–3370. doi: 10.1021/bi00768a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell Z.T., Weichsel A., Baldwin T.O. Crystal structure of the bacterial luciferase/flavin complex provides insight into the function of the β subunit. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6085–6094. doi: 10.1021/bi900003t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohn D.H., Mileham A.J., Baldwin T.O. Nucleotide sequence of the luxA gene of Vibrio harveyi and the complete amino acid sequence of the α subunit of bacterial luciferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:6139–6146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holzman T.F., Baldwin T.O. Proteolytic inactivation of luciferases from three species of luminous marine bacteria, Beneckea harveyi, Photobacterium fischeri, and Photobacterium phosphoreum: evidence of a conserved structural feature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:6363–6367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldwin T.O., Hastings J.W., Riley P.L. Proteolytic inactivation of the luciferase from the luminous marine bacterium Beneckea harveyi. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:5551–5554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holzman T.F., Baldwin T.O. The effects of phosphate on the structure and stability of the luciferases from Beneckea harveyi, Photobacterium fischeri, and Photobacterium phosphoreum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1980;94:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Low J.C., Tu S.C. Functional roles of conserved residues in the unstructured loop of Vibrio harveyi bacterial luciferase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1724–1731. doi: 10.1021/bi011958p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparks J.M., Baldwin T.O. Functional implications of the unstructured loop in the (β/α) (8) barrel structure of the bacterial luciferase α subunit. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15436–15443. doi: 10.1021/bi0111855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell Z.T., Baldwin T.O. Two lysine residues in the bacterial luciferase mobile loop stabilize reaction intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:32827–32834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheraga H.A., Khalili M., Liwo A. Protein-folding dynamics: overview of molecular simulation techniques. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2007;58:57–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugita Y., Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nymeyer H., Gnanakaran S., García A.E. Atomic simulations of protein folding, using the replica exchange algorithm. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:119–149. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yadav M.K., Leman L.J., Ghadiri M.R. Coiled coils at the edge of configurational heterogeneity. Structural analyses of parallel and antiparallel homotetrameric coiled coils reveal configurational sensitivity to a single solvent-exposed amino acid substitution. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4463–4473. doi: 10.1021/bi060092q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onufriev A., Bashford D., Case D.A. Exploring protein native states and large-scale conformational changes with a modified generalized born model. Proteins. 2004;55:383–394. doi: 10.1002/prot.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hornak V., Okur A., Simmerling C. HIV-1 protease flaps spontaneously open and reclose in molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:915–920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508452103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vorontsov I.I., Miyashita O. Solution and crystal molecular dynamics simulation study of m4-cyanovirin-N mutants complexed with di-mannose. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2532–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Böde C., Kovács I.A., Csermely P. Network analysis of protein dynamics. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2776–2782. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gfeller D., De Los Rios P., Rao F. Complex network analysis of free-energy landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1817–1822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608099104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao F., Caflisch A. The protein folding network. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;342:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiser A., Sali A. ModLoop: automated modeling of loops in protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2500–2501. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J., Brooks C.L., 3rd, Khandogin J. Recent advances in implicit solvent-based methods for biomolecular simulations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masunov A., Lazaridis T. Potentials of mean force between ionizable amino acid side chains in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1722–1730. doi: 10.1021/ja025521w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geney R., Layten M., Simmerling C. Investigation of salt bridge stability in a generalized Born solvent model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;2:115–127. doi: 10.1021/ct050183l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashworth J., Havranek J.J., Baker D. Computational redesign of endonuclease DNA binding and cleavage specificity. Nature. 2006;441:656–659. doi: 10.1038/nature04818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang M., Teplow D.B. Amyloid β-protein monomer folding: free-energy surfaces reveal alloform-specific differences. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;384:450–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hornak V., Abel R., Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curtiss L.A., Redfern P.C., Raghavachari K. Gaussian-4 theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:084108. doi: 10.1063/1.2436888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cieplak P., Cornell W.D., Kollman P.A. Application of the multimolecule and multiconformational RESP methodology to biopolymers—charge derivation for DNA, RNA, and proteins. J. Comput. Chem. 1995;16:1357–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J., Wolf R.M., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Homeyer N., Horn A.H., Sticht H. AMBER force-field parameters for phosphorylated amino acids in different protonation states: phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, phosphotyrosine, and phosphohistidine. J. Mol. Model. 2006;12:281–289. doi: 10.1007/s00894-005-0028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Case D.A., Darden T.A., Kollman P.A. University of California; San Francisco: 2008. AMBER 10. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryckaert J.-P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J.C. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng W., Andrec M., Levy R.M. Recovering kinetics from a simplified protein folding model using replica exchange simulations: a kinetic network and effective stochastic dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:11702–11709. doi: 10.1021/jp900445t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shao J., Tanner S.W., Thompson N., Cheatham T.E. Clustering molecular dynamics trajectories: 1. Characterizing the performance of different clustering algorithms. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007;3:2312–2334. doi: 10.1021/ct700119m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore C., Lei B., Tu S.C. Relationship between the conserved α subunit arginine 107 and effects of phosphate on the activity and stability of Vibrio harveyi luciferase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;370:45–50. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z., Meighen E.A. Tryptophan 250 on the α subunit plays an important role in flavin and aldehyde binding to bacterial luciferase. Effects of W—>Y mutations on catalytic function. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15084–15090. doi: 10.1021/bi00046a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen L.H., Baldwin T.O. Random and site-directed mutagenesis of bacterial luciferase: investigation of the aldehyde binding site. Biochemistry. 1989;28:2684–2689. doi: 10.1021/bi00432a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abu-Soud H., Mullins L.S., Raushel F.M. Deuterium kinetic isotope effects and the mechanism of the bacterial luciferase reaction. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3807–3813. doi: 10.1021/bi00130a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sampson N.S., Knowles J.R. Segmental motion in catalysis: investigation of a hydrogen bond critical for loop closure in the reaction of triosephosphate isomerase. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8488–8494. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holzman, T. F. 1983. Bacterial luciferase: studies of proteolytic iand ligand binding. Ph.D. thesis. University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, IL.

- 48.Njus D., Baldwin T.O., Hastings J.W. A sensitive assay for proteolytic enzymes using bacterial luciferase as a substrate. Anal. Biochem. 1974;61:280–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90356-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baldwin T.O., Ziegler M.M., Powers D.A. Covalent structure of subunits of bacterial luciferase: NH2-terminal sequence demonstrates subunit homology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:4887–4889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.AbouKhair N.K., Ziegler M.M., Baldwin T.O. Bacterial luciferase: demonstration of a catalytically competent altered conformational state following a single turnover. Biochemistry. 1985;24:3942–3947. doi: 10.1021/bi00336a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin L.Y., Sulea T., Meighen E.A. Modeling of the bacterial luciferase-flavin mononucleotide complex combining flexible docking with structure-activity data. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1563–1571. doi: 10.1110/ps.7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.