Abstract

How nature tunes sequences of disordered protein to yield the desired coiling properties is not yet well understood. To shed light on the relationship between protein sequence and elasticity, we here investigate four different natural disordered proteins with elastomeric function, namely: FG repeats in the nucleoporins; resilin in the wing tendon of dragonfly; PPAK in the muscle protein titin; and spider silk. We obtain force-extension curves for these proteins from extensive explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations, which we compare to purely entropic coiling by modeling the four proteins as entropic chains. Although proline and glycine content are in general indicators for the entropic elasticity as expected, divergence from simple additivity is observed. Namely, coiling propensities correlate with polyproline II content more strongly than with proline content, and given a preponderance of glycines for sufficient backbone flexibility, nonlocal interactions such as electrostatic forces can result in strongly enhanced coiling, which results for the case of resilin in a distinct hump in the force-extension curve. Our results, which are directly testable by force spectroscopy experiments, shed light on how evolution has designed unfolded elastomeric proteins for different functions.

Introduction

Elastomeric proteins are present in a wide range of living organisms, and are utilized for their toughness and flexibility. Structural disorder and associated hydration are critical features of these elastomeric proteins (1). Although experimental techniques such as NMR and x-ray crystallography can measure well-defined tertiary structures that have specific functions in the cell, a majority of natural proteins are intrinsically unstructured, featuring an elasticity specifically tailored for their distinct force-bearing and sensing functions (2). Their secondary structures are typically transient and confined to the exchanges among Polyproline II (PPII), β-strand, β-turn, and irregular structures (3).

Disordered proteins show low sequence complexity and significant amino-acid compositional bias. Their unstructured conformations are mainly due to their sequence biases. Glycine and proline are two particular residues that often appear in the sequence of disordered proteins. Both of them contribute to disorder but for opposite reasons. Glycine, lacking any side chain, is so flexible that order is entropically unfavorable. Proline's cyclic side chain, by contrast, is stiff and therefore highly restricted in, and mostly disturbing, regular secondary structure formation. A recent study has proven that the glycine and proline compositions of peptides affect their amyloid formation tendency and elasticity (1). More recently, the elasticity of silk was shown to correlate highly with glycine content by measurements from circular dichroism spectroscopy (4).

How amino-acid sequence can affect the entropic and enthalpic contributions to the elasticity of a disordered protein is still unknown. The elasticity of disordered or unfolded proteins can be studied experimentally with single-molecule AFM (5,6). The persistence length commonly used to analyze AFM force-extension data reflects an effective protein elasticity incorporating entropic as well as attractive interactions, most likely of hydrophobic nature, which lower the persistence length (6,7). Various models have been proposed to study the elasticity of DNA and protein. The wormlike chain (WLC) model (8) is the most commonly used by

| (1) |

where F is the force, z is the end-to-end extension, Lp is the persistence length, kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, and L0 is the contour length of the polymer. At low extensions, force grows linearly as a Hookean spring, and at high extensions the force diverges as

This model is able to describe the mechanical response of dsDNA and protein chains fairly well. A high persistence length reflects low flexibility and vice versa.

Four different intrinsically disordered proteins have been chosen for this study of molecular determinants of elasticity. First, phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats are disordered proteins which form a major component of nuclear pore complexes. They consist of up to 50 repeat units and appear intrinsically unfolded, containing short clusters of hydrophobic amino acids. They facilitate the passage of protein and RNA through the nuclear pore by forming a three-dimensional meshwork with hydrogel-like properties. Mutation of phenylalanine to serine has a smaller impact on aggregation (9), but will destroy the formation of the hydrogel (10). Hybrid approaches have been applied to explore the behavior of FG-domains at the nanometer scale (11). A coarse-grained model combined with all-atom simulations of nuclear pore complex arrays showed a brushlike structure with a height of 77.1–88.1 Å, larger than the radius of gyration of a single chain of 13.7–20.0 Å (12). Single-molecule force spectroscopy has been used to study the flexibility of individual cNup153 molecules and mechanically verify that they are unfolded and exhibit entropic elasticity with a mean persistence length of 0.39 ± 0.14 nm (5). We here chose the repeated motif

Resilin from the wing tendons of the adult dragonfly is a member of a family of elastomeric proteins characterized by high resilience, low stiffness, high strain, and efficient energy storage (13). In a recent study, resilin-based near-perfect rubber was produced, achieving 97% of the resilience of natural resilin, using ultraviolet illumination (13,14). We chose the elastic repeat motif

| GGRPSDSYGAPGGGNGGRPS |

from the Drosophila CG15920: 42–51 gene (15).

The Pro-Glu-Val-Lys (PEVK) domain, an unstructured domain of titin, has been shown to be an important factor for the passive elasticity of muscle (16). Two main motifs were identified in the PEVK sequence: one is the PPAK motif with a 28-residue-long sequence, and the other is the polyE motif containing a preponderance of glutamate. The PEVK segment of cardiac titin is assumed to take up multiple mechanical conformations, as indicated by a broad range of persistence lengths (p = 0.3–2.3 nm) obtained in experiment (16). The comparison between individual PEVK exons that varied greatly in their proline content and total PEVK content suggested that this wide range of persistence lengths is independent from the specific amino-acid composition (17). This indicates that, within a certain range, elastic properties are robust with regard to the detailed PEVK content of the polypeptides. In this article, we chose the PPAK motif comprising the first 20 conserved amino acids

| PPAKVPEVPKKPVPEEKVPV |

from motif alignment (18).

Silk fibers constitute an interesting class of materials due to their exceptional mechanical characteristics involving high tensile strength and toughness with a low mass density (19). The ability of high impact absorbency and thus, high elasticity of silk fibers, arise from the amorphous, glycine-rich repeating units that are supposed to act like a cross-linking matrix between strong crystalline blocks (20). We chose the amorphous repeating unit of the spider silk from major ampullate gland of the spider Araneus diadematus (19) having the sequence

The above four representatives of elastomeric proteins have the advantage to widely vary in the amino-acid content. Resilin from dragonfly wings is rich in glycines (40%), PPAK is rich in prolines (35%), and the FG repeat from nuclear pore complex is in-between, with 10% proline and 5% glycine, while being relatively rich in hydrophobic residues. Silk is high in both glycines (54%) and prolines (25%). Both glycine, lacking a side chain, and proline, with a rigidifying ring, can be expected to alter a chain's entropic elasticity due to the increased, or decreased, respectively, dihedral degrees of freedom. In previous work we have dissected the driving forces for coiling of the unfolded state of typical globular proteins in water by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations into contributions from entropic coiling and hydrophobic forces (6,7). The entropic coiling propensity of an unfolded protein, with a persistence length of ∼1.2 nm, is effectively increased— resulting in the frequently measured apparent persistence length of 0.3–0.6 nm under the poor solvent conditions of a largely hydrophobic protein chain in water (7).

Here, we first access the backbone elasticity of the above four disordered proteins by entropic chain simulations, and compare their entropic elasticity in terms of persistence lengths from WLC fits. Second, we investigate influences besides chain entropy, such as charged interactions and the hydrophobic effect on the protein elasticity via all-atom MD simulations.

Materials and Methods

All simulations were carried out using the MD software package GROMACS 3.3.1 (21). The intrapeptide interactions were defined using the OPLS/AA force field (22). Water was represented by the transferable intermolecular potential (TIP4P) model (23). Simulations were run in the NpT ensemble. The temperature was kept constant at T = 300 K by coupling to a Nosé-Hoover thermostat with a coupling time of τT = 0.1 ps. The pressure was kept constant at p = 1 bar using an isotropic coupling to a Berendsen barostat with a coupling time of τT = 0.1 ps and an isotropic compressibility of 4 × 10−5 bar–1. All bonds were constrained using the LINCS algorithm. An integration time step of 2 fs was used. Lennard-Jones interactions were calculated using a cutoff of 1.4 nm. At distances <1.0 nm, the electrostatic interactions were calculated explicitly, whereas long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated by particle-mesh Ewald summation in umbrella sampling runs.

Calculated coiling propensities might heavily depend on the chosen force field. Before studying the elasticity of disordered proteins, four force fields were tested for two turns of ubiquitin (PDB code 1UBQ), i.e., turn I (residues 4–16) and turn II (residues 21–33), and results were compared to experiments. The force fields were GROMOS43A2 (24), GROMOS53A6 (25), and OPLS (22) with single point charge (SPC) water (26) as well as OPLS with TIP4P water (23). Force-clamp spectroscopy experiments showed that after a force quench from 100 pN to 10 pN on a single polyubiquitin protein, proteins that folded collapsed to 0.42 ± 0.22 of the length at 100 pN, whereas those that failed to fold only showed a reduction in length to 0.72 ± 0.12 (6). We consider the latter value for nonfolding proteins as the one to be expected for the ubiquitin fragments. In our simulations, at a high force of 100 pN, all force fields gave an end-to-end distance of ∼3.8 nm. At a low force of 10 pN, simulations were repeated three times for each force field. The distributions of normalized length of 10 pN vs. 100 pN show that the GROMOS43A2 force field with SPC water has the strongest coiling propensity with a normalized length of 0.12 ± 0.04 nm and 0.27 ± 0.11 nm, respectively, for the two turns. GROMOS53A6 with SPC water gave 0.73 ± 0.15 nm for both turn I and II and OPLS with TIP4P water gave 0.65 ± 0.29 nm and 0.68 ± 0.25 nm for turn I and II, respectively. Thus, both GROMOS53A6 with SPC and OPLS with TIP4P result in coiling tendencies of the two peptides, which are in quantitative agreement with the experiments.

In fact, the free energy of solvating the side chains of all amino acids except glycine and proline are overestimated by three of the four tested force fields as compared to the experimental results (27–29). Whereas GROMOS43A2 with SPC overestimates solvation free energies most strongly on average, GROMOS53A6 with SPC and OPLS with TIP4P have been found to perform best in this respect, in agreement with our simulation results. We chose OPLS with TIP4P for subsequent simulations.

Disordered structures were constructed using PyMOL and pulled under a constant stretching force of 500 pN applied to the N- and C-termini, acting outwards along the z axis in solution. The resulting extremely extended structures were placed in a box large enough to accommodate the protein, and water was added, along with ions, to obtain a salt concentration of 0.1 M. After a steepest-descent energy minimization, all nonhydrogen atoms were restrained for a 100-ps equilibrium simulation. Forty-nanosecond MD simulations with force quenched to 2 pN were then performed. In these collapse simulations, equilibrium configurations were clustered to get representative collapsed structures. These representative structures (11.7 ns, 34.5 ns, 27.9 ns, and 20 ns for FG, resilin, PPAK, and silk, respectively) were then pulled with a constant velocity of 4 × 10−5 nm/ps and a force constant of 500 kJ/mol · nm2 to generate starting structures spanning a wide range of extensions for subsequent umbrella simulations. Trajectories were used with the z component of the end-to-end distance ranging from 0.1 nm per bond to 0.35 nm per bond and at least nine windows were chosen with a width of ∼0.025 nm per bond each. The simulation time in each umbrella window varied from 15 ns for large extensions to 100 ns for smaller extensions, depending on the convergence. A force constant of 100 kJ · mol−1 · nm–2 was used for all umbrella sampling simulations. Simulations were repeated with different starting structures and in total 1.44 μs, 1.69 μs, 0.56 μs, and 1.08 μs of MD simulations for FG, resilin, PPAK, and silk, respectively, were carried out. The potential of mean force was calculated using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) to avoid biased sampling (30). The resulting potentials of mean force are shown later in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Force extension curves for FG (A), resilin (B), PPAK (C), and silk (D) from umbrella sampling and WHAM using standard MD simulations including electrostatic and solvent effects (red). For comparison, the force-extension curves of the respective entropic chains are shown (black). Sample conformations of resilin at extensions of ∼3.0 nm, ∼3.5 nm, and ∼4.0 nm are shown in panel B. Charged residues of D6 (magentas) and R18 (orange) are shown in sticks.

The umbrella sampling simulations were repeated for entropic versions of the protein. The force field was modified by switching off all electrostatic interactions and the attractive part of the Lennard-Jones interactions (C6), leaving only bonded interactions and the repulsive part of the Lennard-Jones interactions (C12). A detailed description of this procedure has been given elsewhere (7). The resulting model represents a purely entropic chain, in which the conformational ensemble is only restricted by the bonded interactions, mainly the dihedral potentials along the protein backbone, and by the local steric repulsion of the atoms. This entropic chain model incorporates the correct volume exclusion, backbone geometry, and conformational freedom of the protein and sugar molecules, and ignores nonlocal interactions and solvent-induced effects. However, removal of the C6 term of the Lennard-Jones interaction will increase the effective size of each atom. To compensate for this effect, we divided the C12 coefficients by a factor of 4, to better mimic a Weeks-Chandler-Anderson potential (31). Entropic chain simulations time varied from 100 ns for large extensions to 500 ns for smaller extensions depending on the convergence. The total simulation time was 7.4 μs, 7.4 μs, 7 μs, and 9.5 μs for FG, resilin, PPAK, and silk, respectively. The results were also analyzed by WHAM and are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Chain entropy of the four disordered proteins. (A) Force extension curves of FG (cyan), resilin (brown), PPAK (orange), and silk (violet) obtained from entropic chain simulations and weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM). (Inset) Semilogarithmic plot of panel A. (B) Force extension curves for individual disordered protein from entropic chain simulations (colored lines as in panel A), wormlike chain (WLC) fit to all data (black dashed line), and WLC fit to data with F < 60 pN (red solid line), WLC fit to all data (black dashed lines), and WLC fit to only the data with forces <60 pN (red solid lines). Average forces with standard error of the mean in umbrella sampling windows (blue circles). (C) Snapshots of FG, resilin, PPAK, and silk from left to right with an extension-per-bond of 0.25 nm. Highlighted are particular sequence features in each structure, namely Phe and Gly (FG), Gly (resilin), Pro (PPAK), and Gly (silk).

The first 1-ns of every simulation were omitted from calculations of means and standard errors, to allow for equilibration.

Results and Discussion

Elasticity of entropic chains

The wormlike chain (WLC) model is a frequently-used model to measure protein stiffness. It regards the protein as a slender cylindrical elastic rod with a fixed contour length L0. It is an entropic model that does not consider the effects of hydration. We first treated the protein chains as entropic chains by switching off the electrostatic and attractive van der Waals interactions, leaving only excluded volume interactions (7). Force-extension curves for these entropic chains were obtained by umbrella sampling combined with the weighted histogram method (Fig. 1), in which the peptide chain was held at a range of extensions by a pair of harmonic potentials acting on the terminal atoms. To allow comparison between the four chains with different absolute lengths, we henceforth give extensions and contour lengths as distances per interresidue bond. Among the polypeptides, silk is the only one that can be well fitted by the WLC model, with a persistence length of 0.776 ± 0.003 nm and a contour length per bond of 0.365 nm. The others depart significantly from the best-fit WLC curves, especially at low extensions with forces <50 pN. By fitting only the data with an extension-per-bond below 0.31 nm, we obtained Lp = 1.79 ± 0.77 nm, L0 = 0.349 ± 0.001 nm per bond for FG, Lp = 1.26 ± 0.035 nm, L0 = 0.357 ± 0.001 nm per bond for resilin, Lp = 3.36 ± 0.17 nm, L0 = 0.335 ± 0.001 nm per bond for PPAK, and Lp = 0.74 ± 0.02 nm, and L0 = 0.364 ± 0.001 nm per bond for silk.

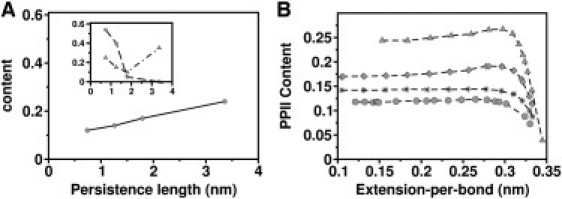

Silk and resilin show a higher contour length per bond and a comparably low persistence length due to the glycines for which steric clashes of the side chains are absent (Fig. 2 A, inset). In agreement, Dicko et al. (4) concluded that the emergence of elasticity in silks correlates highly with the glycine content, and that a stiffening effect due to prolines in the sequence is absent. A possible dichotomization of silk processing has been suggested, with glycine controlling the soluble precursor assembly and proline governing the solid fiber behavior (32,33).

Figure 2.

Influence of glycine and proline on entropic chain elasticity. (A) PPII content as a function of persistence length. (Inset) Glycine content (square) and proline content (triangle) versus persistence length. Persistence lengths are obtained from WLC fits (red curves in Fig. 1B). A high correlation is found for the PPII content and glycine content. (B) PPII content of FG (diamond), resilin (star), PPAK (triangle), and silk (circle) as a function of extension-per-bond.

The distinctive cyclic structure of proline's side chain locks its ϕ-backbone dihedral angle at ∼−75°, giving proline an exceptional conformational rigidity compared to other amino acids. Proline loses less conformational entropy upon unfolding. Hence, proline can render a protein more rigid. However, apparently, proline content is not the only determinant of protein rigidity because it is largely uncorrelated with the persistence length (Fig. 2 A, inset). For example, PPAK has the highest persistence length among the four disordered proteins not only due to the high proline content but also due to their locations in the sequence. Similarly, silk has a proline content of 25%, close to that of PPAK, but it is still the most elastic of the studied polypeptides because all the prolines are located close to glycines.

Instead of the proline content, we find the content of PPII conformation, a prevalent structure in disordered proteins, to highly correlate with entropic chain elasticity (Fig. 2 B). It is formed when sequential residues all adopt ϕ-, ψ-, and ω-backbone dihedral angles of roughly −75°, 150°, and 180° (34,35). It has no internal hydrogen bonds due to steric constraints. At low extensions, the PPII contents of chains converge to 0.25 for PPAK, 0.175 for FG, 0.14 for resilin, and 0.12 for silk (Fig. 2 B). The higher the PPII content, the more rigid the protein. The short contour length per bond of PPAK can thus be explained by its high PPII content. We note that not only proline polymers but also lysine polymers prefer a PPII conformation, as observed by experiment (36). Indeed, we here find FG, featuring a lysine content of 20%, to show a higher PPII content than resilin and silk.

In experiments (16), PPAK is found to show a wide range of persistence lengths. Possible contributions could be a heterogeneity in the cis-trans conformation of the X-Pro bonds, or variations in salt bridges formed between charged residues in PPAK. Our entropic chain simulations suggest that another factor could be the strong variation in PPII content, as exhibited by PPAK with a factor of 10 in the region of 0.3–0.35 nm extension-per-bond (Fig. 2 B).

Elasticity from full MD simulations

The entropic elasticity of a disordered protein correlates with its amino-acid sequence, in particular with the glycine content and the PPII structure content measured from the entropic chain simulations. However, other effects besides the entropy of the chain must also be taken into consideration. Umbrella sampling was performed for FG, resilin, PPAK, and silk polypeptides, this time including all interatomic interactions. In standard all-atom MD simulations, we again obtained the elasticities from force-extension curves (Fig. 3). Interestingly, results show the same overall tendency of the four disordered proteins as those obtained by only considering entropic chains, emphasizing the role of entropic chain elasticity in the coiling of disordered proteins. However, there are significant alterations to the force extension curves, in particular at shorter extensions. As shown in the respective free energy profiles (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material), this results in an additional gain in free energy upon collapse of the peptides of up to 10 kBT, in which specific energy barriers are introduced. Thus, in contrast to the folding of a protein into its native state, unspecific collapse is a barrier-free diffusion limited process, at least for the four cases considered here.

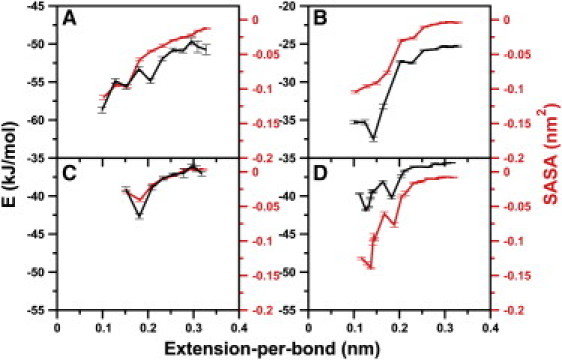

For FG, hydrophobic residues are distributed over the first two-thirds of the peptide chain, starting from the N-terminus, whereas the C-terminus is richer in polar hydrophilic residues (Fig. 1 C, left). The initial burial of the central hydrophobic residues F8 and F10 leads to a reduction of the total solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) by 1.0 nm2, in contrast to the entropic chain model (see Fig. 4 A). A further decrease of SASA is observed upon the burial of the hydrophobic or polar residues K5, P6, S9, and P14. These events lead to the formation of a hydrophobic core by the N-terminal two-thirds of the peptide at an extension-per-bond of 0.15 nm, with the remaining one-third is still extended. This packing of the hydrophobic core is not very stable due to the competition between further burial of hydrophobic residues and repulsive interactions of the charged residues, as reflected by a zigzag shape of the SASA and electrostatic energy curves at low extensions (Fig. 4 A). Lim et al. (5) considered the flexible FG nucleoporins as entropic barriers to nucleocytoplasmic transport. In agreement, for extensions beyond ∼0.25 nm per residue, supposedly those found in FG brushes, the force-extension curve closely follows the entropic chain behavior (Fig. 3 A). However, enhanced coiling due to the hydrophobic effect is dominant at smaller extensions.

Figure 4.

Electrostatic energy per residue (E, black) and solvent-accessible surface area per residue (SASA, red) for FG (A), resilin (B), PPAK (C), and silk (D) as a function of extension-per-bond.

For resilin, the force-extension curve features a pronounced hump with a peak force of ∼50 pN at an extension-per-bond between 0.1 and 0.2 nm, a strong divergence from purely entropic behavior (Fig. 3 B). We analyzed the change in molecular interactions upon collapse to identify the sequence properties leading to this hump. An only minor initial collapse due to the burial of the central hydrophobic residue Y8 along with a decrease of the total SASA of 0.5 nm2 (see Fig. 4 B) does not lead to a significant divergence of the force-extension curve from the purely entropic chain. The subsequent decrease of hydrophobic SASA by ∼0.93 nm2 is connected to the further burial of hydrophobic residues Y8, A10, and P19, accounting for 35%, 10.7%, and 18.7% of the total decrease, respectively. The burial of these hydrophobic residues also causes the favorable burial of the neighboring charged residue R18, which leads to a reduction in electrostatic interactions by 100 kJ/mol. The attractive electrostatic interactions become stronger with a further loss of 80 kJ/mol of electrostatic energy due to the approach of polar residue R18 to D6.

We note that, here, we do not take into account any water-protein enthalpic contributions or entropic effects which are likely to partly compensate the change in internal protein electrostatic energy. Nevertheless, considering this contribution as a qualitative measure for the driving forces of collapse, we suggest that the hump at an extension-per-bond of ∼0.15 nm in the force-extension curve (Fig. 3 B) might be caused by this electrostatic interaction. The interaction of these two charged residues leads to a distorted hairpin structure at the central glycine-rich part of the chain from G12 to G17. Due to the lack of side chains, the glycines cause very little steric hindrance when forming such a tight bend. In accordance, resilin was also observed to form a knot structure under ultraviolet illumination, mainly due to the long glycine chain (13).

In general, glycine and proline residues are frequently found in loop-and-turn structures of proteins and are also believed to play an important role during chain compaction early in folding (37). In the respective free energy profile (Fig. S1 B), resilin features a steep drop in free energy upon hairpin formation at an extension of 0.15. We conclude that an interplay of high entropic chain flexibility and attractive electrostatic interactions along the chain can, in general, give rise to such sharp humplike elastic properties.

Due to the decreased tendency of PPAK to coil, we only were able to sample chain extension down to ∼0.1 nm per bond (Fig. 3 A). Overall, the deviation from the entropic chain behavior is only minor, again emphasizing the high rigidity of this proline-rich disordered protein. A consequence is an only slight burial of hydrophobic residues by an area as small as 0.1 nm2 at extensions-per-bond <0.15 nm, except for K11, which shows a pronounced decrease of 0.25 nm2 at an extension-per-bond of 0.185 nm. The marginally stronger coiling propensity of PPAK with respect to its entropic chain model at high extensions is caused by a higher PPII content (37% in full MD simulations versus 25% in entropic chain simulations at an extension-per-bond of 0.30 nm), stressing the role of PPII structure formation for the coiling of proline-rich peptides.

Silk exhibits a force-extension curve that significantly diverges from its entropic chain behavior at low extensions more strongly than its counterparts PPAK and FG, but without featuring the eye-striking hump of the related glycine-rich resilin peptide. With a burial of surface area of 0.15 nm2 at an extension-per-bond of 0.15 nm (Fig. 4 D), it is the least hydrated among the four disordered proteins, due to its strong coiling propensity. Interestingly, this proline-rich Araneus MA silk has previously been shown to be even more hydrated than the proline-deficient Nephila MA silk (38). Apparently, although prolines add to the hydrophobicity and thus to the surface burial of silk, they here do not play a significant role in enhancing the PPII content (Fig. 2 A).

We also asked whether these four archetypal disordered peptides distinguish themselves from peptides which are part of well-folded globular proteins. To this end, we determined the force-extension curves of two fragments of ubiquitin, an α-helix and a β-turn, which are shown in Fig. S2. Although their entropic chain elasticity is highly similar to the FG repeat, as expected given their similarly low Gly/Pro content, they overall collapse more strongly starting already at extensions as high as 0.3 nm, supposedly due to the higher hydrophobic forces typical for the core of folded proteins like ubiquitin.

Conclusions

In general, the main driving force for the initial collapse of these disordered proteins is of entropic nature, which is largely defined by the glycine and PPII content, and less by the proline content. Nonlocal electrostatic and hydrophobic forces are setting in at lower end-to-end distances. Their impact on the coiling propensity again depends on glycines and prolines in the chain, with glycine allowing and proline impeding formation of a compact core of tight side chain-side chain packings. As a consequence, proline renders PPAK rigid, whereas glycine renders silk and resilin elastic. FG forms a compact hydrophobic core comprising the first two-thirds of the chain. However, in comparison, resilin and silk can more strongly coil due to the extended glycine chain.

Recently, an empirical relation to predict the compaction of disordered proteins from its sequence has been put forward (39). The authors propose a correlation of the hydrodynamic radius with the protein's net charge and its proline content, and no significant correlation with the glycine content, in contrast to our findings. However, the dependencies showed strong scattering so that divergences from the correlations can be expected to occur frequently for individual disordered proteins. We tested whether the resulting relation for the hydrodynamic radius (Eq. 6 of Marsh and Forman-Kay (39)) is able to predict the relative coiling propensity observed for the four natural disordered proteins we have investigated in the MD simulations.

The sequence-based relation predicts a coiling propensity in the order

| FG>resilin>silk>PPAK, |

which directly reflects the correlation with their proline content (net charges for our four proteins vary only between 0 and 1 and do not influence the prediction). However, we find an order

| silk>resilin>FG>PPAK, |

as measured from the integral of the force-extension curves up to intermediate extensions (Fig. 3). In our case, despite the considerable proline content of resilin and silk of 15% and 25%, respectively, both disordered proteins show a strong tendency to coil. Apparently, the nonadditive impact of prolines and glycines in their respective sequence distribution and environment, resulting in varying degrees of PPII and hairpin formation, gives rise to the generally observed divergence from simple additivity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott A. Edwards for helpful discussions and for carefully reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Frauke Gräter's present address is Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies gGmbH, Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg 35, 69118 Heidelberg, Germany.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Rauscher S., Baud S., Pomès R. Proline and glycine control protein self-organization into elastomeric or amyloid fibrils. Structure. 2006;14:1667–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunker A.K., Oldfield C.J., Uversk V. The unfoldomics decade: an update on intrinsically disordered proteins. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bochicchio B., Pepe A., Tamburro A.M. Investigating by CD the molecular mechanism of elasticity of elastomeric proteins. Chirality. 2008;20:985–994. doi: 10.1002/chir.20541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dicko C., Porter D., Vollrath F. Structural disorder in silk proteins reveals the emergence of elastomericity. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:216–221. doi: 10.1021/bm701069y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim R.Y.H., Huang N.P., Aebi U. Flexible phenylalanine-glycine nucleoporins as entropic barriers to nucleocytoplasmic transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9512–9517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603521103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walther K.A., Gräter F., Fernandez J.M. Signatures of hydrophobic collapse in extended proteins captured with force spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7916–7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702179104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gräter F., Heider P., Berne B.J. Dissecting entropic coiling and poor solvent effects in protein collapse. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11578–11579. doi: 10.1021/ja802341q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustamante C., Marko J.F., Smith S. Entropic elasticity of λ-phage DNA. Science. 1994;265:1599–1600. doi: 10.1126/science.8079175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dölker N., Zachariae U., Grubmüller H. Hydrophilic linkers and polar contacts affect aggregation of FG repeat peptides. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2653–2661. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frey S., Richter R.P., Görlich D. FG-rich repeats of nuclear pore proteins form a three-dimensional meshwork with hydrogel-like properties. Science. 2006;314:815–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1132516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elad N., Maimon T., Medalia O. Structural analysis of the nuclear pore complex by integrated approaches. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miao L., Schulten K. Transport-related structures and processes of the nuclear pore complex studied through molecular dynamics. Structure. 2009;17:449–459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elvin C.M., Carr A.G., Dixon N.E. Synthesis and properties of crosslinked recombinant pro-resilin. Nature. 2005;437:999–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature04085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nairn K.M., Lyons R.E., Elvin C.M. A synthetic resilin is largely unstructured. Biophys. J. 2008;95:3358–3365. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.119107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ardell D.H., Andersen S.O. Tentative identification of a resilin gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001;31:965–970. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H., Oberhauser A.F., Fernandez J.M. Multiple conformations of PEVK proteins detected by single-molecule techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10682–10686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191189098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarkar A., Caamano S., Fernandez J.M. The elasticity of individual titin PEVK exons measured by single molecule atomic force microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:6261–6264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greaser M. Identification of new repeating motifs in titin. Proteins. 2001;43:145–149. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010501)43:2<145::aid-prot1026>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gosline J.M., Guerette P.A., Savage K.N. The mechanical design of spider silks: from fibroin sequence to mechanical function. J. Exp. Biol. 1999;202:3295–3303. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.23.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oroudjev E., Soares J., Hansma H.G. Segmented nanofibers of spider dragline silk: atomic force microscopy and single-molecule force spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(Suppl 2):6460–6465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082526499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Berendsen H.J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jorgensen W.L., Tirado-Rives J. The OPLS [optimized potentials for liquid simulations] potential functions for proteins, energy minimizations for crystals of cyclic peptides and crambin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:1657–1666. doi: 10.1021/ja00214a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J.D. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Gunsteren W.F., Billeter S.R., Tironi I.G. Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH, Zürich; Switzerland: 1996. Biomolecular Simulation: The GROMOS96 Manual and User Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oostenbrink C., Soares T.A., van Gunsteren W.F. Validation of the 53A6 GROMOS force field. Eur. Biophys. J. 2005;34:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s00249-004-0448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernard P., editor. Intermolecular Forces. Reidel, Dordrecht; The Netherlands: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geerke D.P., van Gunsteren W.F. Force field evaluation for biomolecular simulation: free enthalpies of solvation of polar and apolar compounds in various solvents. ChemPhysChem. 2006;7:671–678. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200500510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oostenbrink C., Villa A., van Gunsteren W.F. A biomolecular force field based on the free enthalpy of hydration and solvation: the GROMOS force-field parameter sets 53A5 and 53A6. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1656–1676. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacCallum J.L., Tieleman D.P. Calculation of the water-cyclohexane transfer free energies of neutral amino acid side-chain analogs using the OPLS all-atom force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2003;24:1930–1935. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S., Rosenberg J.M., Kollman P.A. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weeks J.D., Chandler D., Andersen H.C. Role of repulsive forces in determining the equilibrium structure of simple liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 1971;54:5237–5247. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y., Sponner A., Vollrath F. Proline and processing of spider silks. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:116–121. doi: 10.1021/bm700877g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savage K.N., Gosline J.M. The role of proline in the elastic mechanism of hydrated spider silks. J. Exp. Biol. 2008;211:1948–1957. doi: 10.1242/jeb.014225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bochicchio B., Tamburro A.M. Polyproline II structure in proteins: identification by chiroptical spectroscopies, stability, and functions. Chirality. 2002;14:782–792. doi: 10.1002/chir.10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zagrovic B., Lipfert J., Pande V.S. Unusual compactness of a polyproline type II structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11698–11703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409693102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rucker A.L., Creamer T.P. Polyproline II helical structure in protein unfolded states: lysine peptides revisited. Protein Sci. 2002;11:980–985. doi: 10.1110/ps.4550102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieger F., Möglich A., Kiefhaber T. Effect of proline and glycine residues on dynamics and barriers of loop formation in polypeptide chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3346–3352. doi: 10.1021/ja042798i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savage K.N., Gosline J.M. The effect of proline on the network structure of major ampullate silks as inferred from their mechanical and optical properties. J. Exp. Biol. 2008;211:1937–1947. doi: 10.1242/jeb.014217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marsh J.A., Forman-Kay J.D. Sequence determinants of compaction in intrinsically disordered proteins. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2383–2390. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.