Abstract

Single-vesicle fusion assays in vitro are useful tools for examining mechanisms of membrane fusion at the molecular level mediated by soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs). This approach allows the experimentalist to define the lipid and protein composition of the two fusing membranes and perform experiments under highly controlled conditions. In previous experiments, in which we reconstituted a SNARE acceptor complex into supported membranes and observed the docking and fusion of fluorescently labeled synaptobrevin proteoliposomes by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy with millisecond time resolution, we were able to determine the optimal number of SNARE complexes needed for fast fusion. Here, we utilize this assay in combination with polarized total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy to investigate topology changes that vesicles undergo after the onset of fusion. The theory that describes the fluorescence intensity during the transformation of a single vesicle from a spherical particle to a flat membrane patch is developed and confirmed by experiments with three different fluorescent probes. Our results show that on average, the fusing vesicles flatten and merge into the planar membrane within 8 ms after fusion starts.

Introduction

Biological membranes create multiple compartments within cells. Information exchange between compartments occurs by vesicular carriers that fuse their membranes with specified target membranes. One of the most prominent, highly regulated fusion reactions happens during synaptic transmission when neurotransmitter-loaded vesicles fuse with the plasma membranes of neurons as a result of an incoming action potential. The depolarization of the presynaptic membrane leads to an opening of Ca2+ channels and the influx of Ca2+ ions into the cell triggers the fusion of primed synaptic vesicles. This response to calcium happens in <1 ms. A number of proteins, the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF), soluble NSF attachment proteins (SNAPs), and the SNAP receptors (SNAREs) syntaxin1A (Syx1A), SNAP25, and synaptobrevin2 (Syb2), have been identified as part of the neuronal fusion and disassembly machinery. Proteins such as the Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin, complexin, Sec1/Munc18 homologs (SM proteins), Munc13, and synaptophysin are involved in regulating the fusion process and Rab GTPases function as upstream tethering factors (1–3).

Early on, in vitro reconstitution experiments have played an essential role in a large body of research on SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. SNARE proteins have been hypothesized as constituting the minimal machinery and source of energy for membrane fusion. This hypothesis was derived from results of experiments with proteoliposomes that contained purified SNARE proteins (4). In this assay, liposomes containing Syx1A/SNAP25 were able to fuse with liposomes containing Syb2, although the observed fusion reaction was very slow (∼1 h). It has been shown that the fusion rate in liposome assays could be increased dramatically (∼1 min) by using a SNARE acceptor complex consisting of one Syx1A, one SNAP25, and a short Syb2 fragment (Syb49–96) to ensure a 1:1 stoichiometry between Syx1A and SNAP25 (5). However, even this assay cannot overcome the limitations of its ensemble nature, and the observed reaction seems slow compared to the requirements for efficient synaptic signal transduction. This is mostly due to the fact that fusion is not synchronized between the liposomes and to the time it takes for liposomes to diffuse to and dock with each other.

More recently, single-vesicle assays have been developed (6–9) that use planar supported membranes (10,11) in combination with total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM). In all of these experiments, the supported membrane mimics the plasma membrane and contains either Syx1A or Syx1A and SNAP25. Single fluorescently labeled liposomes with reconstituted Syb2 can be observed as soon as they are close to the membrane and the fluorophore in the vesicle membrane gets excited by the evanescent field of the totally reflected laser light. Fast imaging allows separation of docking and fusion reactions with high time resolution, thereby overcoming the limitations of the ensemble liposome assays.

We have recently shown that we could reproduce the known biochemistry of in vitro SNARE fusion in POPC/Chol (4:1) supported membranes that contained a physiological concentration of the Syx1A/SNAP25/Syb49-96 acceptor complex (9). By observing more than 1000 single fusion events with 4-ms time resolution, we gained insights into the kinetics of vesicle fusion. The observed fusion was fast (t1/2 ≈ 18 ms) and consisted of multiple steps that could be interpreted as eight parallel reactions, each requiring ∼8 ms. Subsequent work showed that the number of parallel reactions in this assay depends quite critically on the lipid environment and can be reduced to three under some conditions (12).

In addition to the kinetics, we can extract information about the topology changes of the vesicle membrane that happen during the fusion reaction when we utilize polarized TIRFM (pTIRFM). Several published experimental and theoretical approaches to pTIRF applications have used different optical setups and parameters applied to a variety of biological samples and questions. Sund et al. have shown that the orientation of cell membranes can be determined by pTIRFM (13), and this method has been used more recently to examine topological changes in the plasma membrane upon exocytosis (14). In the latter work, Anantharam et al. (14) used objective-type TIRFM to observe the topological changes at the fusion site upon fusion of single granules with the DiI-labeled plasma membrane of chromaffin cells. By taking consecutive images while rapidly alternating the exciting laser between p- and s-polarization and using appropriate theoretical expressions it was possible to overcome the challenge of studying (inhomogeneously) labeled cell membranes. Oreopoulos et al. also used p-polarized and s-polarized excitation light on an objective-type TIRF microscope to acquire order parameter images of phase-separated supported membranes (15). A nonimaging approach was used by Thompson et al. to measure order parameters in lipid monolayers (16) on a prism-type TIRFM setup. In their measurements, the fluorescence from a lipid monolayer was recorded at different polarization angles of the exciting laser light.

In this work, we examine how fast the topology of reconstituted Syb2 vesicles changes upon SNARE-dependent fusion with supported membranes. We first extend the theory of Sund et al. (13) to compute the fluorescence intensity changes that are expected when a vesicle becomes a flat part of the supported membrane. This theory is well suited for our assay, in which we record homogenously-labeled fast-fusing vesicles. The theoretical prediction is then compared with data from single-vesicle fusion events observed when either s- or p-polarized laser light was used as an excitation source in a prism-type TIRF microscope. An alternative approach would be to rapidly alternate between the two polarization states (14). Although this would allow us to better characterize membrane shape changes during individual fusion events, the high time resolution necessary to observe the fast fusion events could not be achieved. We take advantage of the fact that our in vitro assay allows us to incorporate specific lipids into the vesicles and compare results obtained with the labeled lipids Rh-DOPE, NBD-DPPE, and Bodipy-PC.

Theory

The aim of the following calculation is to evaluate the change of total observed fluorescence during the transition of the membrane from a spherical geometry (vesicle) to a planar membrane (patch) for s- and p-polarized incident laser light. The basic configuration (Fig. 1) consists of a prism-type TIRFM set-up, in which the incident angle of the beam is fixed and the fluorescence is collected by the objective of an inverted microscope. We assume that the dye is homogenously distributed in the area in each of the geometries and neglect any dequenching effects that might happen when the label concentration decreases as a result of diffusion into the planar membrane. The computation consists of a numerical integration of the fluorescence intensity per area fraction over the whole membrane surface. The fluorescence intensity of each area fraction depends on the membrane orientation relative to the optical axis. Although this is constant for the planar membrane, it changes over the spherical surface. To calculate the intensity contribution of a certain area fraction, we follow the theory of Sund et al. (13).

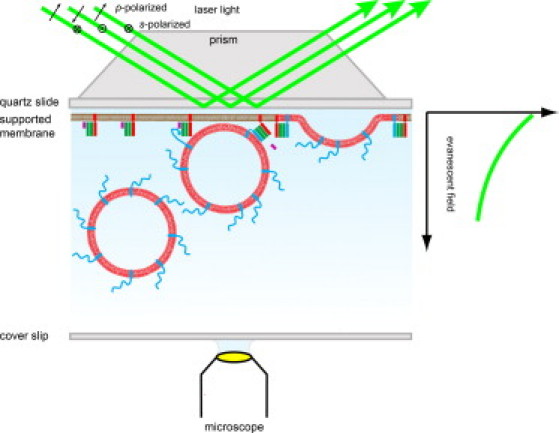

Figure 1.

Polarized TIRFM. A p- or s-polarized laser beam is coupled through a quartz prism to a quartz slide and totally reflected at the quartz/water interface. The quartz slide supports an acceptor SNARE complex containing planar membrane. Synaptobrevin containing fluorescently labeled vesicles can be visualized as soon as they get into the proximity of the supported bilayer within the exponentially decaying evanescent field. The fluorescence is collected by a water immersion objective of an inverted microscope from underneath. System components are not drawn to scale.

Geometry

Two sets of coordinates are introduced:

-

1.

The lab frame (coordinates x, y, and z), with an orientation that is fixed to the optical system and the planar membrane. The z-axis is normal to the substrate and the x-axis is in the plane of incidence formed by the incoming and reflected laser beam.

-

2.

The membrane frame (coordinates x′, y′, and z′), with variable orientation according to the local membrane inclination on the vesicle surface. The z′-axis is normal to the local membrane surface and the x′-axis lies in the z-z′ plane.

The membrane frame's z′-axis is oriented relative to the lab's z-axis by the polar angle θ and the azimuthal angle ϕ (relative to the x-axis). These two angles can also be regarded as the angular spherical coordinates that describe each point on the vesicle surface. The transition dipoles (for absorption and emission) of the fluorophores have specific orientations relative to the membrane normal, described by the two characteristic angles θ′ and ϕ′. In general, the dipole orientations for absorption and emission can be different. As a first approximation, we use the same dipole orientation for absorption and emission for the following calculation. Considering the relative orientation of the membrane, the dipole moment, i.e., the unit amplitude vector of the dipole, can be expressed in Cartesian coordinates as

| (1) |

Excitation

The excitation probability is proportional to , where can be described by Eq.1 and is the electric vector of the evanescent field. The field vector for the two polarization cases (s-pol and p-pol) originating from an incident beam of wavelength λ0 under angle θi can be calculated by (17)

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

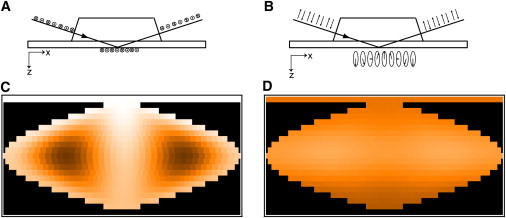

where is the ratio of the refractive indices, δp and δs are the phase lags relative to the incident light, and is the characteristic penetration depth of the evanescent field. The linear polarized evanescent field of Eq. 2a and the elliptic polarized evanescent field of Eq. 2b are sketched in Fig. 2, A and B, respectively.

Figure 2.

Polarization of the evanescent field and fluorescence intensity maps of the vesicle surface. An s-polarized incident laser beam creates a linear polarized evanescent field with the electric vector pointing along the y axis (A), whereas a p-polarized incident laser beam creates an elliptical polarized evanescent field with the main component of the electric vector pointing parallel to the z-axis and the minor component pointing along the x-axis (B). (C and D) Color-coded sinusoidal projections of the vesicle surface for s-polarized (C) and p-polarized (D) excitation. The gray scales (black/dark for low intensity to white for high intensity) represents the fluorescence intensity originating from a specific location of the vesicle surface. The horizontal line at the top (white for s-polarization (C) and dark orange for p-polarization (D)) represents the supported membrane.

Emission of single dipole

The observed fluorescence of a single dipole is proportional to the product of the emission probability and the excitation probability. In addition, we have to take into account the rotational diffusion of the dye that might change the dipole orientation in the time between absorption and excitation of a photon.

The probability of observing the emitted light of a single dipole depends on the numerical aperture of the objective and the emission pattern of the dipole. This pattern is altered from the usual sin2 emission pattern of an isolated dipole by the closeness of the water/glass interface (18). We follow the calculation described in great detail in Hellen and Axelrod (18) to get the function P2 ( that describes the probability of observing the emission of an excited dipole oriented with angles and located at a distance z from the water/glass interface.

The dye-labeled lipids undergo rotational diffusion. Therefore, the orientation of the dipole changes during the lifetime of the excited state of the fluorophore. We approximate this influence by changing the azimuthal angle of emission by Dτ, the mean-squared angle change during the fluorescence lifetime of the fluorophore caused by rotational diffusion with a diffusion coefficient D.

Fluorescence from one membrane location

The total contribution to the observed fluorescence from one location in the membrane is calculated by integrating over all azimuthal dipole angles, ϕ0′, at the time of excitation (all constants that are the same for s- and p-polarization are suppressed):

| (3) |

Integration over membrane surface

The total intensity originating from one vesicle of radius RV is obtained by integrating over all membrane orientations of a sphere:

| (4) |

A circular patch, which covers the same area as the spherical vesicle, has the radius 2RV. The total intensity of the patch is simply:

| (5) |

Calculation

For numerical calculations, we make these approximations: 1), The polar angles of the excitation and emission dipoles are the same and are represented by a single value, which means we neglect any wobbling motion of the dipole relative to the bilayer normal. 2), The rotational diffusion is included by its mean angle change during the fluorescence lifetime of the fluorophore. A comparison between this simplification and the full theory (19) reveals that the relative errors of the approximation lie between 0.5 and 1.0% (see the Supporting Material). 3), Both leaflets of the lipid bilayer are labeled and are approximated by one layer. Therefore, we assume this layer to be at a distance from the quartz, which is the sum of a water layer thickness of 2 nm (20,21) plus half the typical thickness of a lipid membrane, i.e., 2 nm. 4), Excitation and emission are monochromatic.

The following numerical parameters were used for all calculations: incidence TIR angle, θi = 72°; numerical aperture, N.A. = 0.95; refractive indices for water, nwater =1.33, and glass, nglass = 1.46; and wavelengths of excitation, λex = 514 nm, and emission, λem = 600 nm.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The following materials were purchased and used without further purification: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine (POPC), lissamine-rhodamine-B-DOPE (Rh-DOPE), 1,2-dipalmitoyl phosphatidylethanolamine-N-[7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl] (NBD-DPPE) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL); 2-(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-pentanoyl)-1-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (Bodipy-PC) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR); cholesterol, sodium cholate, and glycerol (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO); CHAPS (Anatrace); HEPES, KCl (Research Products International, Mt. Prospect, IL); chloroform, ethanol, contrad detergent, all inorganic acids, bases, and hydrogen peroxide (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). Water was purified first with deionizing and organic-free 4 filters (Virginia Water Systems, Richmond, VA) and then with a NANOpure system from Barnstead (Dubuque, IA) to achieve a resistivity of 18.2 M/cm.

Protein expression and purification

SNARE proteins from Rattus norvegicus cloned in pET28a vector were expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli and purified as described previously (22,23). The cysteine-free variant of SNAP25A consisted of residues 1–206, and Syb2 constructs included residues 49–96 or 1–117 with C-terminal cysteine (Cys117). The acceptor SNARE complex (containing Syx1A, SNAP25, and Syb49–96) was purified from BL21(DE3) expressing all three proteins, using the pET28a vector for SNAP25A and the pETDuet-1 vector for SyxH3 and Syb49–96. The complex and full-length Syb2 were purified by Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography followed by ion exchange chromatography using MonoQ or MonoS columns in the presence of 15 mM CHAPS (24).

SNARE reconstitution into proteoliposomes

Syb2 and acceptor SNARE complex were reconstituted into POPC/Chol (4:1) vesicles by rapid dilution of micellar protein/lipid/detergent mixtures followed by dialysis, as described previously (25). This method results in unilamellar vesicles with diameters between 40 and 50 nm as determined by dynamic light scattering. Briefly, the desired lipids (including 1 mol % fluorescent probes for Syb2 vesicles) were mixed and organic solvents were evaporated under a stream of N2 gas followed by vacuum for at least 1 h. The dried lipid films were dissolved with 25 mM sodium cholate in reconstitution buffer (RB; 20 mM Hepes and 200 mM KCl, pH 7.4) followed by the addition of an appropriate volume of SNARE proteins to reach a final volume of ∼180 μl and the desired protein:lipid ratio. After 1 h of equilibration at room temperature, the mixture was diluted below the critical micellar concentration by adding more RB buffer to a final volume of 550 μl and the sample was dialyzed overnight against 500 ml of RB at 4°C with one change of buffer.

SNARE reconstitution into planar supported bilayers

Planar supported bilayers with reconstituted SNAREs were prepared by a combined Langmuir-Blodgett/vesicle fusion technique, as previously described (25–27). Briefly, quartz slides were cleaned by boiling in Contrad detergent for 10 min, hot-bath-sonicated while still in detergent for 30 min, and finally rinsed extensively with milliQ water. The slides were then immersed in 3:1 95% H2SO4/30% H2O2 (v/v) followed by extensive rinsing in milliQ water. Immediately before use, slides were further cleaned for 10 min in an argon plasma sterilizer (Harrick Scientific, Ossining, NY). The first leaflet of the bilayer was prepared by Langmuir-Blodgett transfer. To do so, a lipid monolayer was spread from a chloroform solution onto a pure water surface in a Nima 611 Langmuir-Blodgett trough (Nima, Conventry, United Kingdom). The solvent was allowed to evaporate for 10 min before the monolayer was compressed at a rate of 10 cm2/min to reach a surface pressure of 32 mN/m. After equilibration for 5–10 min, a clean quartz slide was rapidly (200 mm/min) dipped into the trough and slowly (5 mm/min) withdrawn, with simultaneous computer maintenance of constant surface pressure and monitoring of the transfer of lipid headgroups down onto the hydrophilic substrate.

To complete the bilayer, a solution of proteoliposomes or protein-free vesicles (77 μM total lipid in 1.3 ml, which is a little more than the volume of the holding cell) was added and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Excess unfused vesicles were then removed by perfusion with 10 ml RB.

TIRFM

All experiments were carried out on a Zeiss Axiovert 35 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), equipped with a 63× water immersion objective (Zeiss; N.A. = 0.95) and prism-based TIRF illumination with characteristic penetration depth dp ≈ 103 nm. The light source was an argon ion laser (Innova 300C, Coherent, Palo Alto, CA) emitting p-polarized light at 514 nm. For experiments with s-polarized excitation light, a λ/2 wave plate (05RP22-01, Newport, Irvine, CA) was inserted into the beam path. Fluorescence was observed through a 610-nm bandpass filter (D610/60, Chroma, Brattleboro, VT) by an electron multiplying CCD (DU-860E, Andor-Technologies, CT). The EMCCD was cooled to −70°C and the gain was typically set to an electron gain factor of ∼200. The prism/quartz interface was lubricated with glycerol to allow easy translocation of the sample cell on the microscope stage. The beam was totally internally reflected at an angle of 72° from the surface normal. An elliptical area of 250 μm × 65 μm was illuminated. The intensity of the laser beam was computer-controlled through an acoustooptic modulator (AOM-40, IntraAction, Bellwood, IL) or could be blocked entirely by a computer-controlled shutter. The laser intensity, shutter, and camera were controlled by a homemade program written in LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX).

Single-vesicle fusion assay

Supported bilayers containing acceptor SNARE complex were perfused with 3 ml of 0.6 μM Syb2 vesicles containing 1 mol % labeled lipids (Rh-DOPE, NBD-DPPE, or Bodipy-PC) mixed with 3.3 μM protein-free vesicles in RB on the microscope stage (concentration refers to total lipid). Data acquisition was started ∼1 min after the beginning of vesicle injection. Images of 127 × 127 pixel2 (corresponding to a sample area of 46.7 × 46.7 μm2) were acquired with an exposure time of 4 ms and a cycle time of 4.01 ms in series of 15,000 images in frame-transfer mode and spooled directly from the CCD camera to the hard drive. From one supported membrane preparation, we collected three to five series for each (p and s) polarization.

Analysis of single-vesicle fusion

Images were analyzed using a homemade program written in LabView (National Instruments). First, the whole stack of images was filtered by a moving average filter. The intensity maximum for each pixel over the whole stack was projected on a single image. Vesicles were located in this image by a single-particle detection algorithm described previously (28). The peak (central pixel) and mean fluorescence intensities of a 5 × 5-pixel2 area around each identified center of mass were plotted as a function of time for all particles in the 15,000 images of each series. The exact time points of docking and fusion were determined from the central pixel (9), whereas the mean fluorescence was used to evaluate the topology changes.

Calculations

All numerical calculations were run by a custom-made program written in LabView (National Instruments) on standard Windows-based PCs (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Results

Calculation of fluorescence intensities from planar and spherical membrane in the evanescent field

Fluorescence intensity maps for the supported membrane and the surface of adhering vesicles (radius, 24 nm) were calculated as outlined in the Theory section. For most of the experiments in our previous work and below, we utilized Rh-DOPE as the fluorophore. For the calculation, we therefore used a polar dipole angle of 68° as determined by fluorescence interference contrast microscopy (FLIC) for Rh-DOPE in fluid-phase supported bilayers (29) and a mean-squared angle change due to rotational diffusion of 0.21 rad2 (30). Results for s- and p-polarized excitation light are shown as sinusoidal projections in Fig. 2, C and D, respectively, using the same relative scale. The intensity of the supported membrane is represented by the horizontal line at the top of the map. The sketches in Fig. 2, A and B, illustrate the polarization of the evanescent field in the s- and p-polarization cases, respectively. The dipole angle of Rh-DOPE results in strong excitation probabilities in the polar regions for s-polarized light and in the equator region for p-polarized light. Due to the linear polarization parallel to the quartz surface of the evanescent field for s-excitation, the intensity map shows a strong dependency on the longitudes. Areas parallel to the plane of incidence show only minor contributions to the whole fluorescence intensity. In contrast, for p-excitation, most of the surface contributes strongly to the total fluorescence, whereas the modulation along the longitudes caused by the elliptical polarization of the evanescent field is weak. As a result, we expect an increase of intensity for s-polarized light and a decrease for p-polarized light when the spherical vesicle becomes a planar patch of membrane.

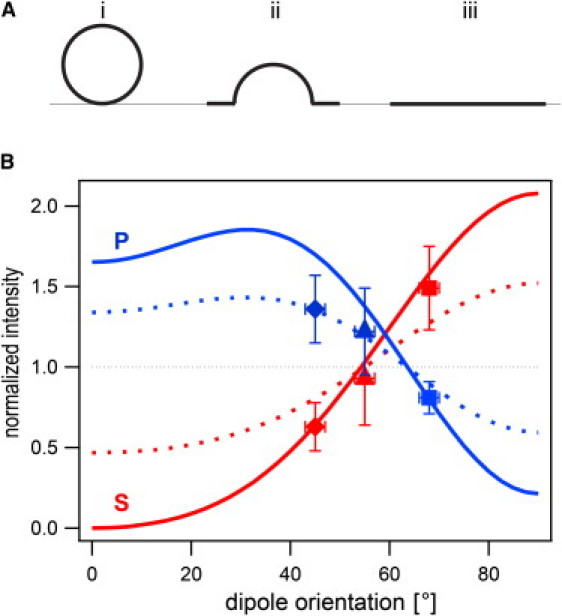

We also calculated the ratio of the total intensity from a membrane patch to the intensity of a vesicle of the same surface area and positioned at zero distance from the planar membrane. This procedure normalizes the data and thereby avoids the use of absolute intensities, which would be higher for s-polarized than for p-polarized light. Fig. 3 B shows the results for s- and p-polarized light for dipole orientations between 0° and 90°. For p-polarized light, we expect a higher intensity from the patch than from the vesicle for dipole orientations up to ∼65°. Between 65° and 90°, the fluorescence becomes darker after the transition to a planar membrane. For s-polarized excitation, the fluorescence disappears in the planar membrane for dipoles oriented perpendicular to the membrane surface. It increases as the dipole becomes more tilted toward the surface, surpassing the vesicle intensity at ∼55° and having its maximum at 90°. In addition to the patch/vesicle ratio, we calculated a hypothetical intermediate state consisting of half a vesicle surrounded by a planar membrane ring of half the original vesicle area (Fig. 3 A, ii). The ratios of intensity of this dome to that of the original vesicle are shown as dotted lines in Fig. 3 B. These lines are approximately halfway between the patch/vesicle ratios and the horizontal line drawn at 1.0. We were also interested in the influence of the vesicle size on the expected intensity change during fusion. In Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material, we compare calculated intensity ratios for vesicles with radii of 24, 50, and 100 nm. For dipole angles, for which the fluorescence intensity increases during the transition from spherical to patch geometry (smaller angles for p-pol and larger angles for s-pol), the increase is stronger for larger vesicles.

Figure 3.

Theoretical and experimental intensity changes of membranes in p- and s-polarized evanescent fields after topology changes. Geometries used for the calculations are a spherical vesicle touching the supported membrane (A i), a fused vesicle with half the membrane surface in the plane of the supported membrane and the other half forming a half-sphere (A ii), and a planar circular membrane patch (A iii). (B) Ratios of integrated intensities originating from a membrane patch (A iii) to those originating from a vesicle of the same surface (A i) (solid lines) and of intensities originating from a hypothetical intermediate state (A ii) to those from the original state (A i) (dotted lines) for p-polarization (marked p) and s-polarization (marked s) for polar dipole angles between 0° and 90°. Experimentally determined intensity changes 4 ms after the onset of fusion are added for three different dipole angles: 48° (Bodipy-PC (♦)), 55° (NBD-DPPE (▴)), and 68° (Rh-DOPE (■)).

Experimental results

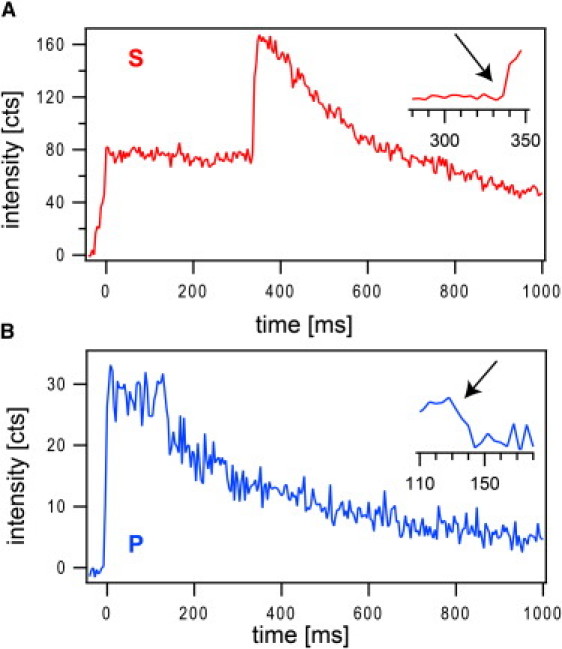

Fusion experiments of Syb2 vesicles with acceptor SNARE complex-containing planar membranes were performed as described in detail in Domanska et al. (9). Fifteen thousand images were spooled to the hard drive of the computer in ∼1 min with or without a λ/2 plate inserted into the excitation beam path. With this configuration we recorded at least six image sequences, three for each polarization, from a single supported membrane. Fusion events were recognized by their specific intensity pattern over time after the mean intensity of a 5 × 5 pixel2 area around a docked vesicle was extracted. Fig. 4 shows two examples of fusion reactions that were recorded with s-polarized (Fig. 4 A) and p-polarized (Fig. 4 B) excitation laser light. The onset of fusion is characterized by a sharp increase in intensity in the s-pol case (∼330 ms after docking (Fig. 4 A, inset)) and a sharp decrease in intensity in the p-pol case (∼120 ms after docking (Fig. 4 B, inset)).

Figure 4.

Examples of single docking and fusion events. Mean Rh-DOPE fluorescence intensities from single vesicles observed under s-polarized excitation (A) and p-polarized excitation (B) are plotted as a function of time. The intensities were extracted from 5 × 5-pixel2 areas around the vesicle. Time zero represents the time point at which the vesicles docked to the supported membrane. It is characterized by a sharp increase of the mean intensity in both cases. The onset of fusion is characterized by a second sharp increase in intensity for s-polarized excitation (A) and by a sharp drop in intensity for p-polarized excitation (B) (arrows in insets).

To find out how much the intensity changed in the first 4 ms during fusion, we measured the last mean intensity of the docked vesicle and the first intensity recorded after that. From a total of 90 fusion events, the mean ratio of the first time point after fusion to the last point before fusion was 1.45 ± 0.28 (n = 59) for s-polarized excitation and 0.79 ± 0.14 (n = 31) for p-polarized excitation. These results are shown as data points for a dipole orientation of 68° (29) in Fig. 3. The mean values are very close to the theoretical curve that would be expected if the vesicle had already become a flat membrane, although the error bars overlap with the theory curve for a vesicle that has collapsed only to a half sphere. The uncertainty about the dipole orientation is acknowledged with error bars of ±2° along the x-axis.

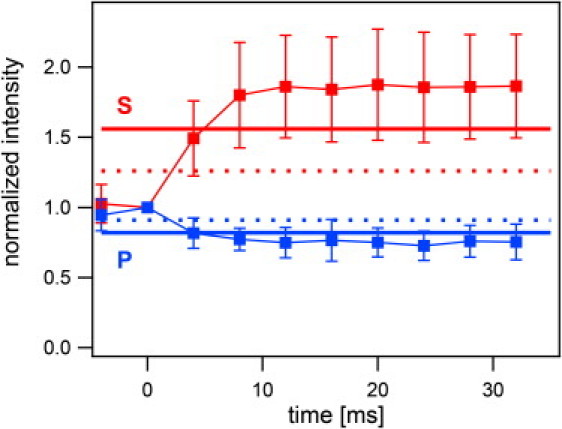

To see whether the shape of the fused vesicle changes further, we normalized the intensity of 107 traces to the last point before fusion and averaged them for the two polarization cases. Averaged traces that cover the time between 8 ms before and 32 ms after the onset of fusion are shown in Fig. 5. During the first 32 ms of fusion, we can neglect the depletion of labeled lipids in the region of interest due to the diffusion into the planar membrane (see online supplement for our previous article (9)). The averaged intensities for both s-pol and p-pol reach a steady state within 8 ms, which is slightly higher (s-pol) and lower (p-pol) than the predicted values for a transformation from spherical shape to flat membrane. The slight deviation from the prediction is most likely due to some systematic errors in the dipole orientations that we used in the calculation. Cholesterol in the membranes tends to lead to larger dipole angles (29) and therefore to higher (s-pol) or lower (p-pol) patch/vesicle intensity ratios (see Fig. 3).

Figure 5.

Averaged normalized intensities for the first 32 ms after fusion. One hundred mean Rh-DOPE fluorescence intensity traces recorded with s-polarized (marked s) and p-polarized (marked p) excitation were normalized to the last time point before fusion and averaged. Two time points before and 32 ms after fusion are shown as a function of time. The horizontal lines represent the calculated intensity changes expected if a vesicle containing a fluorophore with a polar angle of 68° becomes a flat membrane patch (solid line) or a half-sphere surrounded by a flat ring (dotted line).

To further test the concept of these measurements, we replaced Rh-DOPE in the Syb2 vesicles with NBD-DPPE or Bodipy-PC that have dipole angles of 55° (29) and 48° (31) relative to the membrane normal in fluid-phase supported bilayers. For these experiments, the excitation wavelength was switched to 488 nm and the fluorescence was observed at ∼535 nm. As shown in Fig. S2, this spectral change has only a minor effect on the theoretical curves of Fig. 3. We also neglect a potential change in rotational diffusion. Fig. S3 shows how the theory curves would change if the mean (azimuthal) angle changed between 0° and 90° within the lifetime of the fluorophore. The total range of the alteration for these extreme values is small for s-polarized excitation and within the error bars of the measured values for the p-polarized case. For simplicity, we only compare the mean intensity change within the first 4 ms upon fusion for s- and p-polarized excitation with the theoretical curve in Fig. 3. As expected, the fluorescence change upon fusion for NBD-DPPE and Bodipy-PC is reversed when compared to Rh-DOPE. We observe an increase of fluorescence for p-polarized light and a decrease of fluorescence for s-polarized light (Fig. 3). The NBD-DPPE data have larger error bars, because the relatively small change of fluorescence makes it more difficult to determine the exact time point at which fusion starts. The intensity changes for Bodipy-PC are larger, providing us a dynamic range measurement similar to that of Rh-DOPE. Analogous to the data shown in Fig. 5, we averaged 50 intensity traces recorded with Bodipy-PC in the range of 8 ms before to 32 ms after fusion occurs. Although we observe decreasing intensities for both p- and s-polarized excitation ∼10 ms after fusion due to photobleaching, the results shown in Fig. S4 confirm the Rh-DOPE results, namely that the vesicles collapse into the supported membrane within 8 ms.

Discussion

We utilized polarized TIRFM to investigate the topological changes that occur upon fusion of synaptobrevin-containing vesicles with acceptor SNARE complex-containing supported membranes. Fluorescence changes after the onset of fusion were compared to the theory that was developed for the specific conditions of our set-up. Due to low photobleaching and the relatively high dynamic range of the expected intensity change, Rh-DOPE was the preferred fluorescent lipid probe in these measurements. On average, the vesicles collapsed into the planar membrane within 8 ms. After 4 ms they were already at or past the stage of a half-sphere with an expanded fusion pore.

The dynamics of this synthetic system containing reconstituted proteins is much faster than the topological changes that were detected on secretory granules in chromaffin cells, where the flattening of the membrane took place in tenths of seconds (14). There are several major differences between the two systems that could be responsible for the different timescales of vesicle flattening: 1), secretory granules have radii of ∼175 nm (32) compared to ∼24 nm of our reconstituted vesicles (9), which are similar in size to synaptic vesicles (33); 2), the plasma membrane is more heterogeneous and crowded with a large variety of lipids and proteins compared to the relatively simple structure of the planar membrane used in this study; 3), the fusion site/pore itself has likely a more complex structure and may be surrounded by scaffold proteins in native membranes, which could slow down the relaxation of the curved vesicle membrane; and 4), secretory granules are filled with a dense array of proteins, which must exit through the fusion pore after fusion, possibly further slowing the flattening of fusing vesicles.

The simple fusion machinery in our reconstituted system consists only of the SNARE acceptor complex and the vesicle SNARE Syb2. So far, regulatory proteins like the Sec1/Munc18 homologs, Munc13 or the Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin among others are missing in this assay (1–3). These proteins, as well as differences in membrane tension in different systems, could also influence the speed and topology changes of fusion. Although the flat membrane might accelerate fusion in the planar system, overcoming curvature inhibition in small liposomes might slow fusion in such assays.

It is noteworthy to point out that we do not observe any depletion of fluorescence due to diffusion before the polarization changes start. This means that once the membrane merger starts, it progresses very rapidly and that any transient membrane structures like a hemifusion stalk (34) or a partially dilated proteinaceous fusion pore (35) would be too short-lived for us to observe. In our previous work, we found that fast fusion required between three and eight SNARE complexes, depending on the lipid environment, and that it was Ca2+-independent under the same conditions as used in this work (9,12). Polarized TIRFM as described here will expand the versatility of future single-vesicle fusion experiments most notably when additional molecular components of the fusion machinery will be included. It will be interesting to see not only how the fusion kinetics will be influenced by these additions, but also how membrane topologies will dynamically change as more physiological conditions are progressively approached by increasingly complex reconstitutions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Tamm laboratory for many helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant P01 GM72694.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Jahn R., Scheller R.H. SNAREs—engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malsam J., Kreye S., Söllner T.H. Membrane fusion: SNAREs and regulation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:2814–2832. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8352-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizo J., Rosenmund C. Synaptic vesicle fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber T., Zemelman B.V., Rothman J.E. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pobbati A.V., Stein A., Fasshauer D. N- to C-terminal SNARE complex assembly promotes rapid membrane fusion. Science. 2006;313:673–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1129486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fix M., Melia T.J., Simon S.M. Imaging single membrane fusion events mediated by SNARE proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7311–7316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401779101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen M.E., Weninger K., Chu S. Single molecule observation of liposome-bilayer fusion thermally induced by soluble N-ethyl maleimide sensitive-factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) Biophys. J. 2004;87:3569–3584. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu T., Tucker W.C., Weisshaar J.C. SNARE-driven, 25-millisecond vesicle fusion in vitro. Biophys. J. 2005;89:2458–2472. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domanska M.K., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Single vesicle millisecond fusion kinetics reveals number of SNARE complexes optimal for fast SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:32158–32166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamm L.K. The substrate supported lipid bilayer-a new model membrane system. Klin. Wochenschr. 1984;62:502–503. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiessling V., Domanska M.K., Tamm L.K. Supported lipid bilayers: development and applications in chemical biology. In: Begley Tadgh P., editor. Wiley Encyclopedia of Chemical Biology. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 411–422. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domanska M.K., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Docking and fast fusion of synaptobrevin vesicles depends on the lipid compositions of the vesicle and the acceptor SNARE complex-containing target membrane. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2936–2946. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sund S.E., Swanson J.A., Axelrod D. Cell membrane orientation visualized by polarized total internal reflection fluorescence. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2266–2283. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77066-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anantharam A., Onoa B., Axelrod D. Localized topological changes of the plasma membrane upon exocytosis visualized by polarized TIRFM. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:415–428. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oreopoulos J., Yip C.M. Combinatorial microscopy for the study of protein-membrane interactions in supported lipid bilayers: order parameter measurements by combined polarized TIRFM/AFM. J. Struct. Biol. 2009;168:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson N.L., McConnell H.M., Burhardt T.P. Order in supported phospholipid monolayers detected by the dichroism of fluorescence excited with polarized evanescent illumination. Biophys. J. 1984;46:739–747. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Axelrod D. Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy in cell biology. In: Marriott G., Parker I., editors. Biophotonics, Part B. Academic Press; NY: 2003. pp. 1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellen E.H., Axelrod D. Fluorescence emission at dielectric and metal-film interfaces. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 1987;4:337–350. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Axelrod D. Carbocyanine dye orientation in red cell membrane studied by microscopic fluorescence polarization. Biophys. J. 1979;26:557–573. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85271-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fromherz P., Kiessling V., Zeck G. Membrane transistor with giant lipid vesicle touching a silicon chip. Appl. Phys., A Mater. Sci. Process. 1999;69:571–576. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Measuring distances in supported bilayers by fluorescence interference-contrast microscopy: polymer supports and SNARE proteins. Biophys. J. 2003;84:408–418. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74861-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fasshauer D., Antonin W., Jahn R. Mixed and non-cognate SNARE complexes. Characterization of assembly and biophysical properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15440–15446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fasshauer D., Margittai M. A transient N-terminal interaction of SNAP-25 and syntaxin nucleates SNARE assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7613–7621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein A., Radhakrishnan A., Jahn R. Synaptotagmin activates membrane fusion through a Ca2+-dependent trans interaction with phospholipids. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:904–911. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner M.L., Tamm L.K. Reconstituted syntaxin1a/SNAP25 interacts with negatively charged lipids as measured by lateral diffusion in planar supported bilayers. Biophys. J. 2001;81:266–275. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75697-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalb E., Frey S., Tamm L.K. Formation of supported planar bilayers by fusion of vesicles to supported phospholipid monolayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1103:307–316. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90101-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner M.L., Tamm L.K. Tethered polymer-supported planar lipid bilayers for reconstitution of integral membrane proteins: silane-polyethyleneglycol-lipid as a cushion and covalent linker. Biophys. J. 2000;79:1400–1414. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76392-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiessling V., Crane J.M., Tamm L.K. Transbilayer effects of raft-like lipid domains in asymmetric planar bilayers measured by single molecule tracking. Biophys. J. 2006;91:3313–3326. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crane J.M., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Measuring lipid asymmetry in planar supported bilayers by fluorescence interference contrast microscopy. Langmuir. 2005;21:1377–1388. doi: 10.1021/la047654w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cognet L., Harms G.S., Schmidt T. Simultaneous dual-color and dual-polarization imaging of single molecules. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000;77:4052–4054. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ariola F.S., Mudaliar D.J., Heikal A.A. Dynamics imaging of lipid phases and lipid-marker interactions in model biomembranes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006;8:4517–4529. doi: 10.1039/b608629b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coupland R.E. Determining sizes and distribution of sizes of spherical bodies such as chromaffin granules in tissue sections. Nature. 1968;217:384–388. doi: 10.1038/217384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takamori S., Holt M., Jahn R. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell. 2006;127:831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chernomordik L.V., Kozlov M.M. Mechanics of membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:675–683. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson M.B. SNARE complex zipping as a driving force in the dilation of proteinaceous fusion pores. J. Membr. Biol. 2010;235:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9258-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.