Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium contains three distinct respiratory hydrogenases, all of which contribute to virulence. Addition of H2 significantly enhanced the growth rate and yield of S. Typhimurium in an amino acid-containing medium; this occurred with three different terminal respiratory electron acceptors. Based on studies with site-specific double-hydrogenase mutant strains, most of this H2-dependent growth increase was attributed to the Hyb hydrogenase, rather than to the Hya or Hyd respiratory H2-oxidizing enzymes. The wild type strain with H2 had 4.0-fold greater uptake of 14C-labeled amino acids over a period of minutes than did cells incubated without H2. The double-uptake hydrogenase mutant containing only the Hyb hydrogenase transported amino acids H2 dependently like the wild type. The Hyb-only-containing strain produced a membrane potential comparable to that of the wild type. The H2-stimulated amino acid uptake of the wild type and the Hyb-only strain was inhibited by the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone but was less affected by the ATP synthase inhibitor sodium orthovanadate. In the wild type, proteins TonB and ExbD, which are known to couple proton motive force (PMF) to transport processes, were induced by H2 exposure, as were the genes corresponding to these periplasmic PMF-coupling factors. However, studies on tonB and exbD single mutant strains could not confirm a major role for these proteins in amino acid transport. The results link H2 oxidation via the Hyb enzyme to growth, amino acid transport, and expression of periplasmic proteins that facilitate PMF-mediated transport across the outer membrane.

IMPORTANCE

Complex carbohydrates consumed by animals are fermented by intestinal microflora, and this leads to molecular hydrogen production. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium can utilize this gas via three distinct respiratory hydrogenases, all of which contribute to virulence. Since H2 oxidation can be used to conserve energy, we predicted that its use may augment bacterial growth in nutrient-poor media or in competitive environments within H2-containing host tissues. We thus investigated the effect of added H2 on the growth of Salmonella Typhimurium in carbon-poor media with various terminal respiratory electron acceptors. The positive effects of H2 on growth led to the realization that Salmonella has mechanisms to increase carbon acquisition when oxidizing H2. We found that H2 oxidation via one of the respiration-linked enzymes, the Hyb hydrogenase, led to increased growth, amino acid transport, and expression of periplasmic proteins that facilitate proton motive force-mediated transport across the outer membrane.

INTRODUCTION

When an animal consumes complex sugars that are not absorbed or are difficult to metabolize, these sugars reach the intestinal flora and are anaerobically fermented by resident microbes (1, 2). One result is production of molecular hydrogen (H2), and it is well established that such H2 production can vary with the animal’s diet (3), including that of humans (4–6). The colonically produced gas can be distributed to many tissues where pathogens reside (7, 8). Some pathogens capitalize on this, using the high-energy reductant as an energy source to facilitate their growth (8). One of these is Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, in which H2 has been shown to be an important energy source for virulence during host colonization. Study of Salmonella hydrogenase mutants has shown that each of the three uptake hydrogenases contributes to virulence, and a triple uptake mutant lacking all respiratory H2-oxidizing ability was avirulent in a mouse model (9).

Electrons generated from H2 splitting are passed along metabolically versatile bacterial electron transport chains to a variety of acceptors, including fumarate, nitrate, sulfate, CO2, or O2 (10), depending on the inherent terminal oxidase content of the particular microorganism. Such respiratory chains conserve energy in the form of ATP. The three H2-consuming hydrogenases known as Hyb, Hyd, and Hya in Salmonella Typhimurium (11) are membrane bound and contain NiFe centers. The enterobacterial uptake-type (H2-oxidizing) hydrogenases are viewed as auxiliary energy input providers contributing to the proton gradient across the cell membrane (10, 12).

Metabolically flexible H2-utilizing bacteria (e.g., the facultative chemoautotrophs) turn to H2 use when high-energy organic substrates become limiting (13). Since H2 oxidation can be used to conserve energy, it may be predicted that use of H2 may be especially important to augment bacterial growth in nutrient-poor media or in the competitive environments within H2-containing host tissues. Still, the effect of exogenous H2 on growth, including under carbon-limited conditions, has not been studied in Salmonella Typhimurium. We thus initially investigated the effect of added H2 on Salmonella Typhimurium growth in carbon-poor media with various terminal respiratory electron acceptors. The positive effect of H2 led to the realization that the cells have mechanisms to increase carbon acquisition when oxidizing H2.

The culture conditions used herein were ones in which the H2 uptake enzymes were produced but no H2 was produced, so only the effect of (exogenously added) H2 was addressed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effects of exogenous H2 on growth.

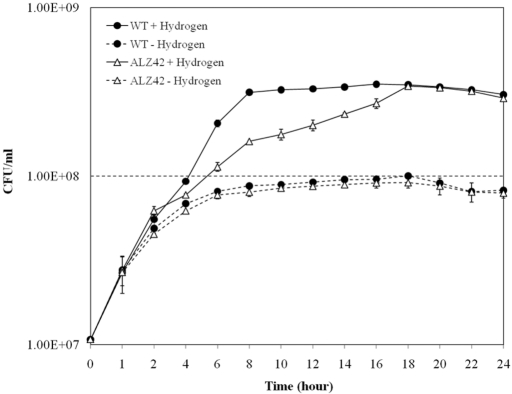

The ability to use hydrogen is important for S. enterica serovar Typhimurium survival within the animal host (9). To address possible growth-stimulating effects of H2, the growth parameters of the parent strain and various double mutants (thus, each mutant strain contains only one of the three uptake-type enzymes) were compared in cultures with and without added H2. This was done anaerobically with four different terminal electron acceptors: trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO); dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); sodium fumarate; and sodium nitrate. The strains used are shown in Table 1. We used CR-Hyd medium (14, 15) with the modification that no glucose was added, so the peptone and casein hydrolysate served as the carbon sources for the growth of the strains. The condition used was such that only the H2 uptake enzymes were produced and no H2 was produced, so only the effects of exogenously added H2 were being addressed. Also, the growth of the strains was assigned to the ability of the strains to assimilate carbon by utilizing the amino acids and peptides in the medium as the sole source of carbon. In our growth experiments, cell yield increased by 3.5-fold for cells grown with fumarate and H2, compared to the cell yield in fumarate alone. Growth yields with H2 were increased 1.8-fold and about 3-fold for cells grown with TMAO and DMSO, respectively, compared to those under H2-lacking conditions (Table 2). Growth was not significantly higher in cells grown with nitrate. When grown with fumarate, the triple mutant (strain ALZ43; Table 1), lacking all H2 uptake ability, never responded to H2 addition. The wild type (WT) growth rate (doubling time) with H2 was 1.5 h, whereas without H2 it was about 5 h (Fig. 1). Less pronounced but significant growth rate differences (in comparing bacteria with H2 added versus those with no H2 added) were observed for the WT on either TMAO or DMSO (data not shown).

TABLE 1 .

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Genotype/description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains | ||

| JSG 210 | 14028s (WT) | ATCC |

| ALZ36 | JSG210 with Δhyb::FRTa Δhyd::FRT (Hya only) | 29 |

| ALZ37 | JSG210 with Δhyb::FRT Δhya::FRT (Hyd only) | 29 |

| ALZ42 | JSG210 with Δhyd::FRT Δhya::FRT (Hyb only) | 29 |

| ALZ43 | JSG210 with Δhyb::FRT Δhyd::FRT Δhya::FRT (triple mutant) | 29 |

| RLK1 | JSG210 ΔexbD::FRT (ΔexbD) | This study |

| RLK2 | JSG210 ΔtonB::FRT (ΔtonB) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCP20 | Ampr; contains flippase gene for λ Red mutagenesis | 30 |

| pKD46 | Ampr; contains λ Red genes γ, β, and exo | 30 |

| pKD4 | Kanr; contains kan cassette | 30 |

FRT, flippase recombinase recognition target.

TABLE 2 .

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium H2-facilitated growth yield with various electron acceptors

| Growth condition | No. of cells/ml culturea |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ALZ36 (Hya only) | ALZ37 (Hyd only) | ALZ42 (Hyb only) | ALZ43 (triple mutant) | |

| Fumarate | |||||

| +H2 | 35 ± 1.8b | 12 ± 1.5 | 11 ± 1.4 | 32 ± 2.5b | 10 ± 1.0 |

| −H2 | 10 ± 1.2 | 9 ± 1.4 | 9 ± 1.0 | 9 ± 1.6 | 9 ± 1.5 |

| Nitrate | |||||

| +H2 | 42 ± 1.9 | 36 ± 2.0 | 19 ± 1.2 | 22 ± 2.1b | 21 ± 1.1 |

| −H2 | 38 ± 2.7 | 35 ± 1.0 | 17 ± 2.0 | 12 ± 1.0 | 22 ± 1.6 |

| TMAO | |||||

| +H2 | 25 ± 1.0b | 14 ± 1.8 | 16 ± 3.4 | 28 ± 1.0b | 11 ± 1.1 |

| −H2 | 15 ± 1.7 | 13 ± 1.2 | 9 ± 1.6 | 9 ± 1.0 | 9 ± 1.4 |

| DMSO | |||||

| +H2 | 23 ± 2.1b | 8 ± 1.5 | 8 ± 2.5 | 13 ± 1.6b | 8 ± 2.5 |

| −H2 | 7 ± 1.0 | 7 ± 1.0 | 6 ± 1.4 | 7 ± 1.2 | 8 ± 1.0 |

Values represent the growth yield in 107 cells/ml ± the standard deviation (n = 3) at 18 h of incubation.

Significantly higher growth yield than without H2 (P < 0.005 [Student’s t test]).

FIG 1 .

Effect of hydrogen on growth of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium WT and ALZ42 (Hyb-only-containing strain) with fumarate as an electron acceptor.

To assign specific hydrogenase activity to growth effects, endpoint growth yields were determined for uptake-type hydrogenase double and triple mutant strains. The strain containing only the Hyb hydrogenase (ALZ42; Table 1) had increased growth yield in the presence of H2 (more than 3.0-fold greater in fumarate-containing medium) compared to that of cells grown without added H2. This H2-facilitated growth occurred when ALZ42 was grown with fumarate, nitrate, TMAO, or DMSO (Table 2). The growth rate of ALZ42 was clearly also H2 stimulated (Fig. 1). The strain that contained only Hya (ALZ36; Table 1) did not respond significantly to the presence of H2 and had growth yields similar (in nitrate, TMAO, or DMSO) to those of the WT in those same media when grown without H2 (Table 2). The strain that contained only Hyd (ALZ37; Table 1) had increased growth yield with H2 when TMAO was provided as an electron acceptor; still, its final yield was much less than those of ALZ42 and the WT. Addition of H2 had no effect on growth or amino acid uptake of the triple mutant strain ALZ43 that lacks all H2-oxidizing ability, and this strain had the lowest growth yield among the strains used.

In the growth experiments, the effects of exogenously added H2 were addressed. This is appropriate, as organs colonized by Salmonella were shown to contain significant levels of H2 (8). Sawers et al. demonstrated that H2 evolution is low (between 0.016 and 0.001 µmol of H2 evolved per min) when S. enterica serovar Typhimurium cells are grown under anaerobic respiration with fumarate (16). We wanted to determine whether cells were producing H2 (which likely would affect the growth yield) under the growth conditions used in our study. One milliliter of headspace gas from 8-h stationary-phase cultures of the triple uptake mutant (ALZ43) grown with fumarate, DMSO, nitrate, or TMAO was assayed for the presence of H2 using an amperometric Clark-type electrode (17). There was no detectable H2 (less than 10 nmol) present in headspace gas from these cultures. This result indicates that the cells were not producing appreciable H2 in the medium and under the atmosphere conditions used in the study herein.

Collectively, our results indicate that addition of exogenous H2 to the headspace greatly enhances the growth rate and yield on fumarate and some other anaerobic respiratory electron acceptors. The bulk of this growth rate increase can be attributed to the Hyb enzyme. Yamamoto and Ishimoto (18) reported that Escherichia coli cells continuously bubbled with hydrogen grew with nitrate, fumarate, or TMAO provided as an electron acceptor and that both H2 uptake and H2 evolution activities were the greatest with fumarate. Hydrogenase activity staining bands from gels indicated the expression of multiple forms of the E. coli enzymes in the fumarate-containing medium, and from growth yields, they suggested that 1 mol of ATP is produced per mol of H2 oxidized.

Amino acid uptake.

The growth studies described above were performed in an amino acid-containing medium, so we measured the uptake of 14C-labeled amino acids when cells were in an atmosphere containing H2 and in one without the gas. Both the WT strain and Hyb-only-containing strain ALZ42 demonstrated significantly increased amino acid uptake ability in the presence of H2. Although the uptake by ALZ42 was initially one-half that of the WT, both strains had 4-fold greater uptake in the first 5 min with H2 than without H2 added (Table 3). After 5 min, the amino acid accumulation continued at a lower rate, but at all points, the uptake was greater for both strains when H2 was provided. The results indicate that the energy for uptake/transport of amino acids in these strains is provided via oxidation of H2, akin to what was observed in Helicobacter hepaticus by Mehta et al. (19). The similar results for ALZ42 and the WT, which contains three distinct H2-oxidizing enzymes, indicate that the Hyb hydrogenase is important for amino acid accumulation. The activity of the Hyb hydrogenase probably suffices to allow the organism to glean energy from H2 for significant solute transport and thus for growth and survival of S. Typhimurium under anoxic and nutrient-limiting conditions. To confirm that the Hyb enzyme plays the largest role in amino acid uptake in nutrient-limited medium, the other mutant strains, each containing a single uptake-type hydrogenase, were assessed for H2-dependent amino acid uptake (Table 4). The strains containing Hya or Hyd as the only uptake hydrogenase were capable of much less uptake of the 14C-labeled amino acid pool than the WT, and H2 had little effect on their amino acid accumulation abilities. Still, the accumulation by Hyd-only-containing strain ALZ37 was slightly stimulated by H2. The triple mutant ALZ43, which lacks all three uptake-type hydrogenases, did not respond to H2.

TABLE 3 .

14C-labeled amino acid uptake by the WT and ALZ42 strains

| Strain and condition |

14C-labeled amino acid uptake (cpm [103]/108 cells)a at: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 min | 10 min | 20 min | |

| WT | |||

| +H2 | 31.0 ± 3.8b | 37.8 ± 2.3b | 35.0 ± 1.9b |

| −H2 | 7.8 ± 1.3 | 9.3 ± 0.9 | 9.9 ± 0.8 |

| ALZ42 (Hyb only) | |||

| +H2 | 14.0 ± 1.6b | 14.9 ± 1.4b | 20.4 ± 3.5b |

| −H2 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 |

Values represent 14C-labeled amino acid uptake by 108 cells ± standard deviation (n = 4).

Significantly higher uptake level than without H2 (P < 0.005 [Student’s t test]).

TABLE 4 .

14C-labeled amino acid uptake by strains ALZ36, ALZ37, and ALZ43

| Strain and condition |

14C-labeled amino acid uptake (cpm [103]/108 cells)a at: |

|

|---|---|---|

| 5 min | 10 min | |

| ALZ36 (Hya only) | ||

| +H2 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 1.6 |

| −H2 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| ALZ37 (Hyd only) | ||

| +H2 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 1.6b |

| −H2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| ALZ43 (triple mutant) | ||

| +H2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.03 |

| −H2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.01 |

Values represent 14C-labeled amino acid uptake by 108 cells ± standard deviation (n = 4).

Significantly higher uptake level than without H2 (P < 0.005 [Student’s t test]).

The proton motive force (PMF) has been suggested to be the driving force of active transport of amino acids in several bacteria (20–22), yet the Enterobacteriaceae are known to contain numerous ATP-utilizing amino acid permeases as well. The uptake and/or transport of amino acids across bacterial cell membranes is facilitated either by carriers which utilize the electrochemical energy stored in the H+ and Na+ gradients or by the ABC-type uptake and efflux systems which utilize the chemical energy derived from ATP (23). In an attempt to identify the type of energy coupled to amino acid uptake/transport in the WT strain and Hyb-only-containing strain ALZ42, inhibitors of the different energy-coupling processes were used. Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) is a protonophore that inhibits PMF, and orthovanadate inhibits ATP synthesis by specifically inhibiting protein tyrosine phosphatases (24). The role of PMF versus that of ATP in H2-mediated amino acid uptake was addressed by the use of these two inhibitors. The amino acid uptake activities of both the WT and ALZ42 strains markedly decreased upon treatment of the cells with CCCP before the addition of the 14C-labeled amino acid mixture (Table 5). Pretreatment of the cells with sodium orthovanadate also resulted in reduced amino acid uptake activity of both the WT and ALZ42 strains. However, considerable uptake activity remained; the uptake rate with inhibitor was still about 50% of the uninhibited rate for the WT at both 5 and 10 min. ALZ42 had 39% and 52% of the uninhibited rate at 5 min and 10 min, respectively. These results indicate that H2-dependent amino acid transport in these strains is driven by both PMF and ATP but that the PMF likely plays the larger role in H2-facilitated amino acid uptake.

TABLE 5 .

Effects of inhibitors on 14C-labeled amino acid uptake by the WT and ALZ42 strains

| Strain and presence of added H2 |

14C-labeled amino acid uptake (cpm [103]/108 cells)a at: |

|

|---|---|---|

| 5 min | 10 min | |

| WT | ||

| None | 29.0 ± 2.0 | 31.0 ± 1.1 |

| CCCP | 0.7 ± 0.5b | 0.3 ± 0.2b |

| Orthovanadate | 14.8 ± 1.2b | 18.7 ± 1.0b |

| ALZ42 (Hyb only) | ||

| None | 14.0 ± 1.6 | 18.2 ± 3.5 |

| CCCP | 0.3 ± 0.1b | 0.04 ± 0.07b |

| Orthovanadate | 5.5 ± 0.8b | 9.5 ± 0.7b |

Values represent 14C-labeled amino acid uptake by 108 cells ± standard deviation (n = 4).

Significantly lower uptake level than without inhibitor (P < 0.005 [Student’s t test]).

Hydrogenase activity and membrane potential (ΔΨ).

Hyb-only-containing strain ALZ42 demonstrated H2 uptake hydrogenase activity that was 65% of that of the WT (42.7 ± 8.1 nmol H2 uptake/min/109 cells), while ALZ36 (containing Hya only) and ALZ37 (containing Hyd only) showed 10.8% and 2.0% of the uptake hydrogenase activity of the WT, respectively. ALZ43 did not show any uptake hydrogenase activity. Therefore, under the conditions used in this study, the bulk of the H2 uptake activity in Salmonella Typhimurium is accomplished by the activity of the Hyb hydrogenase.

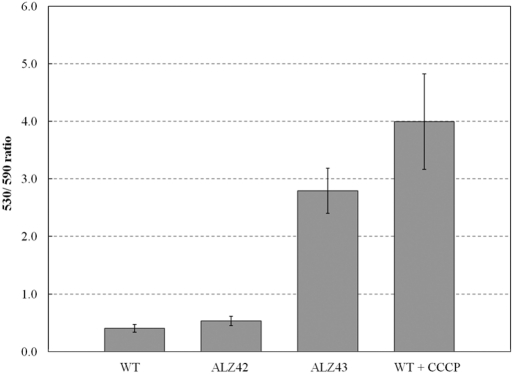

We utilized the fluorescence ratio imaging technique to measure the membrane potential component (ΔΨ) of PMF in the WT and ALZ42 strains by using a cationic dye, JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). A shift in the emission spectrum of the JC-1 dye from red (590 nm) to green (530 nm) indicates a decrease in membrane potential and hence an increased green (530 nm)/red (590 nm) ratio. ALZ42 showed a green/red fluorescence ratio comparable to that of the WT (Fig. 2), indicating similar PMF levels in the two strains. The membrane polarization of ALZ42 (Hyb-only-containing strain) was 75% of that of the WT (red/green ratios, 2.56 ± 0.41 and 1.91 ± 0.28 in the WT and ALZ42 strains, respectively), and the difference between the two strains was statistically insignificant at a 99% confidence level. ALZ43 (triple mutant lacking Hya, Hyb, and Hyd) showed significantly decreased membrane potential compared to that of the WT (Fig. 2). The WT treated with CCCP was included as a control to show the green/red ratio of a disintegrated membrane potential. As expected, CCCP-treated WT cells had the highest green/red ratio among the samples. These results support our hypothesis that the Hyb hydrogenase is involved in carrying out the bulk of the respiratory hydrogen oxidation, and therefore in maintaining the PMF of the cells, under H2-added conditions.

FIG 2 .

Comparison of membrane potentials of the WT, ALZ42, and ALZ43 strains. A small ratio indicates a larger membrane potential (n = 6; P < 0.01).

Involvement of the TonB-ExbD system.

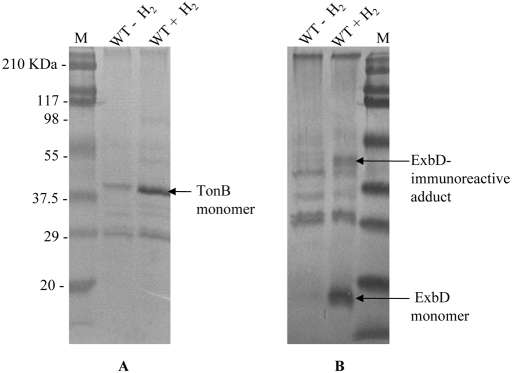

In E. coli and other Gram-negative bacteria, the cytoplasmic PMF is utilized by the TonB-ExbB-ExbD system for substrate transport by the TonB-dependent outer membrane transport proteins (TBDTs) (25, 26). Initially shown to be specifically the uptake of iron complexes and vitamin B12, the role of the TonB-dependent transport has since been expanded to the transport of various other substrates, such as nickel, carbohydrates, cobalt, and copper (27). While the precise mechanism of transport remains unclear, it has been suggested that TonB transduces the PMF to the TBDTs via its periplasmic interaction with ExbD, forming a TonB-ExbB-ExbD complex, and that TonB requires PMF to form the complex with ExbD (28). In an effort to investigate the effect of added H2 on the PMF-facilitated cross-linking between TonB and ExbD in our strain, we subjected the WT to formaldehyde-mediated cross-linking and visualization of the TonB-ExbD complex using TonB- and ExbD-specific antibodies. We were unable to visualize the ExbD-TonB complex in our strains, although a large ExbD-immunoreactive adduct was observed in the culture growing with H2. Importantly, a marked increase in the production of the TonB and ExbD proteins under the condition with H2 added was observed (Fig. 3). Based on densitometry, the increases in expression due to incubation with H2 were 4.0-fold and 11.0-fold for TonB and ExbD, respectively. Quantitative real-time PCR showed elevated tonB and exbD transcript levels in the WT (about 2-fold- and 4-fold-higher expression of tonB and exbD, respectively) and a 1.8-fold increased exbD transcript level in ALZ42 when the strains were grown under exogenously added H2. DNA gyrase B (gyrB) was used as an internal control to normalize the expression levels of tonB and exbD, since a microarray analysis (not discussed here) revealed the expression of gyrB to be unaltered under the conditions used in this study. As in other Gram-negative bacteria, the TonB-ExbD system of Salmonella Typhimurium could play a crucial role in fulfilling the increased demand for the delivery of substrates such as iron siderophores, vitamin B12, nickel complexes, and carbohydrates in a nutrient-limited environment.

FIG 3 .

Immunoblot analyses of TonB-, ExbD-, and TonB/ExbD-linked complexes in WT S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. (A) TonB visualized with TonB-specific monoclonal antibodies. (B) ExbD visualized with ExbD-specific polyclonal antibodies. M, molecular mass standards.

To investigate whether the TonB-ExbD system is also involved in H2-stimulated amino acid uptake, we made ΔexbD and ΔtonB single-deletion mutants (strains RLK1 and RLK2, respectively; Table 1) and subjected them to the amino acid uptake assays described previously. Clear phenotypes distinguishable from that of the WT (i.e., decreases in uptake by the mutants) were not observed (data not shown). Bacteria contain a wide variety of transmembrane amino acid transporters (23), and this includes transporters that are aided by energy-coupling proteins other than TonB-ExbD. Nevertheless, the ΔexbD mutant strain demonstrated 40% reduced nickel uptake compared to that of the WT (63Ni uptake, 20.4 × 102 ± 2.3 × 102 cpm/108 cells in RLK1 and 33.9 × 102 ± 6.7 × 102 cpm/108 cells in the WT), indicating a role for ExbD in nickel uptake in Salmonella. It is possible that in the presence of hydrogen, the bacteria upregulate the expression of ExbD and TonB to transport more nickel into the cells for proper hydrogenase maturation.

Our study shows that Salmonella Typhimurium can grow in an H2-dependent manner and that most of the H2 oxidation by nutrient-limited anaerobically growing Salmonella Typhimurium is aided by the activity of the Hyb hydrogenase alone. Growth under anaerobic respiration with terminal electron acceptors was enhanced with H2, and this H2-facilitated growth ability was assigned to a specific H2-using hydrogenase. The energy available from H2 oxidation is coupled to the uptake of carbon, and the uptake is driven by both PMF and ATP. H2 increases the expression of genes that encode specific proteins (ExbD and TonB) known to complex PMF to aid solute transport processes. Similarly, immunologically identified TonB and ExbD proteins were significantly induced by incubation with H2. The increased expression of the PMF-dependent transport proteins (ExbD and TonB) under the H2-added condition is likely a way for the bacteria to balance energy input with nutrient acquisition. The results herein link H2 oxidation via the Hyb hydrogenase enzyme to H2-dependent growth, solute transport, and expression of periplasmic proteins that facilitate PMF-mediated transport across the outer membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, growth conditions, and reagents.

WT S. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028s and hydrogenase mutant strains described by Zbell and Maier (29) were used in this study. All mutant strains were shown to be nonpolar (29). tonB and exbD gene single-deletion mutants were constructed using the lambda Red system as previously described (30). The deletions were confirmed by PCR using primers complementary to the regions flanking the deleted genes and by sequencing across the deletions (Georgia Genomics Facility, University of Georgia). The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1, and the primers used are listed in Table 6.

TABLE 6 .

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Application |

|---|---|---|

| exbD del-F | GTCATGGCAATGCGTCTTAACGAGAACCTGTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | exbD deletion |

| exbD del-R | CTTACCCGGCCTACAGCGTCAGCAGAATACCATATGAATATCCTCCTTA | exbD deletion |

| exbD-check-F | TGCAAATTTCCGGCGGTCAAA | exbD deletion confirmation |

| exbD-check-R | TATTGCGCAAACGCAGACCA | exbD deletion confirmation |

| exbD-F | TATTTCGCTTTCGCGGTCTCTTCG | exbD real-time PCR |

| exbD-R | CGGTGAAAGCGGATAACACCATGT | exbD real-time PCR |

| tonB del-F | GGTTTTTCAACTGAAACGATTATGACTTCATGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | tonB deletion |

| tonB del-R | TGGTATATTCCTGGCTGGCGGCGCCAGAGACATATGAATATCCTCCTTA | tonB deletion |

| tonB -check-F | CCGCTATCGGCAATGCCTTATT | tonB deletion confirmation |

| tonB-check-R | TGGCGATGTCGTATGCTGCTAC | tonB deletion confirmation |

| tonB-F | TTCACCTTTACGCGGCCTTCAATA | tonB real-time PCR |

| tonB-R | AAAGGTTGAAGAGCAGCCGAAGC | tonB real-time PCR |

| gyrB-F | CGGGTTCATTTCACCCAGACCTTT | Real-time PCR internal control |

| gyrB-R | TACGCATGGCGTGGATACCGATTA | Real-time PCR internal control |

Strains were maintained in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB plates. Experiments were performed in CR-Hyd medium (14, 15) containing bacteriological peptone (0.5%, wt/vol), casein hydrolysate (0.2%, wt/vol), thiamine (0.001%, wt/vol), MgCl2 (1 mM), (NH4)6Mo7O24 (1 µM), and NaSeO3 (1 µM). The medium was supplemented with sodium fumarate (0.5%), sodium nitrate (0.5%), TMAO (0.5%), and DMSO (0.25%) where indicated. No carbohydrate was added, but 5 µM NiCl2 was included in the medium. Cells were grown at 37°C anaerobically with or without H2. Anaerobic conditions with H2 were established by sparging sealed 165-ml bottles with N2 for 15 min and then with anaerobic mix (10% H2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) for 20 min, and then 10% H2 was injected to bring the volume of added H2 to 20% partial pressure. Cells were grown anaerobically without H2 in 165-ml bottles by sparging with N2 for 15 min and then injecting the sealed bottles containing cells with CO2 to 5% partial pressure.

Growth curves and endpoint growth yields.

To determine the effect of hydrogen on growth, growth curves and endpoint growth assays were performed. Sealed 165-ml bottles containing CR-Hyd medium with various electron acceptors (as described above) were inoculated with WT or hydrogenase deletion mutant S. enterica serovar Typhimurium cells at a ratio of 1.0 × 107 CFU/ml. Cells were grown anaerobically with or without 20% H2 for 18 h at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. A600 (OD at 600 nm) was measured after growth to determine cell numbers. An A600 of 1.0 corresponds to about 6.70 × 108 CFU for the strains used. Standard curves of A600 versus the number of CFU/ml (plate counts) confirmed that the A600 was proportional to the viable cell number within the OD range used herein, including for final yield (i.e., saturation growth) numbers. All growth rate and yield studies were performed three times or more, with results similar to those shown (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Amino acid and nickel uptake assays.

WT S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and mutant strains ALZ36, ALZ37, ALZ42, and ALZ43 were grown in CR-Hyd medium (without glucose, supplemented with 0.5% sodium fumarate and 5 µM NiCl2). Cultures were grown in quadruplicate under anaerobic conditions as mentioned above, without added H2. After the cultures reached an A600 of 0.1, 20% H2 (vol/vol of headspace) was injected into two of the bottles for each strain. After 60 min, uniformly 14C-labeled amino acids (specific activity, >50 mCi [1.85 GBq]/mmol; Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) were injected into the bottles to a final concentration of 0.5 µCi/ml of growth medium. The mixture contains 15 uniformly labeled amino acids (l-Ala, l-Arg, l-Asp, l-Glu, l-Gly, l-His, l-Ile, l-Leu, l-Lys, l-Phe, l-Pro, l-Ser, l-Thr, l-Tyr, and l-Val). 14C-labeled amino acid uptake by the cultures was measured at 5, 10, and 20 min by a previously described method (19). For the inhibitor effects, cells were grown as described above and CCCP or sodium orthovanadate (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) was added 1 and 10 min before the addition of the radiolabeled amino acid mixture, respectively. CCCP was added to a final concentration of 50 µM, and sodium orthovanadate was added to a final concentration of 10 mM. These concentrations have been used for studies of other enteric bacteria (28, 31). The experiments (Tables 1 to 3) were repeated a total of three times with similar results, and the data shown are from four replicate samples from one experiment.

For the nickel uptake assays, cultures were grown anaerobically without H2 as described above. After the cultures reached an A600 of 0.1, 20% (vol/vol of headspace) H2 was injected into the bottles. After 60 min, 63Ni (Amersham Biosciences, Sweden) was injected into the bottles to a final concentration of 0.5 µCi/ml of growth medium and the uptake activity was measured at 1- and 5-min intervals.

Real-time quantitative PCR.

RNA was isolated from the test (20% H2 added to the medium) and control (no added H2) cultures (A600 = 0.4) of the WT and ALZ42 strains using the RNA extraction kit from Qiagen (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 200-ng purified RNA samples using random hexamers and Moloney murine leukemia virus SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) at 42°C for 50 min. The iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and iQ Sybr Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) were utilized for real-time PCR of control and test cDNAs. The expression level (threshold cycle) of each sample was normalized using DNA gyrase B (gyrB) as an internal control. The relative n-fold change in gene expression for each sample was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method as previously described (32). The gene-specific primers used for real-time PCR are listed in Table 6.

Western blot assays.

To identify the effect of H2 on the expression levels of the ExbD and TonB proteins under the condition provided, overnight cultures of the WT and ALZ42 strains grown anaerobically in the presence or absence of 20% H2 (in CR-Hyd medium without glucose and supplemented with 0.5% sodium fumarate and 5 µM NiCl2) were subjected to the in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking method previously described (28). The ExbD and TonB proteins and their cross-linked complexes were detected by immunoblotting using ExbD-specific polyclonal antibodies and TonB-specific monoclonal antibodies (33). The antibodies were kindly provided by Kathleen Postle, Pennsylvania State University, University Park. The entire cross-linking experiment was repeated three times with the same results, as shown in Fig. 3.

Hydrogenase assay.

The H2 uptake hydrogenase activity of the WT and ALZ42 strains was assayed in whole cells by following the reduction of methylene blue spectrophotometrically by a method modified from Stults et al. and Peng et al. (34, 35). Cells were grown with 20% H2 in CR-Hyd medium (without glucose and supplemented with 0.5% sodium fumarate and 5 µM NiCl2) to mid-exponential phase (A600 = 0.4). A 2-ml sample of the culture was centrifuged (8,000 × g, 10 min), and cells were resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were permeabilized by adding 10 µl of 10% Triton X-100 and incubating them for 30 min at room temperature. A 500-µl aliquot of the suspension was transferred to a sealed glass cuvette previously flushed with H2. Sodium dithionite was then injected to a final concentration of 200 µM, followed by the injection of H2-flushed methylene blue to a final concentration of 400 µM. Hydrogen uptake activity was determined by measuring the reduction of methylene blue at 570 nm and is expressed as nmol H2 taken up/min/109 cells.

Measurement of membrane potential (ΔΨ).

The membrane potential of the WT, ALZ42, and ALZ43 strains was measured using confocal fluorescence microscopy as described by Jovanovic et al. (36), with modifications as described herein. Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase in the presence of 20% H2 as described above. Cells were harvested by centrifuging 2 ml of culture (8,000 × g, 10 min) and resuspended in 1 ml of permeabilization buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM glycerol) in sealed tubes previously sparged with N2 and injected with 20% H2. The cells were then incubated with 1 µg/ml JC-1 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by centrifugation. Cells were then resuspended in 500 µl permeabilization buffer, and 5 µl of the suspension was immediately transferred to an agarose-coated glass slide prepared as described by Glaser et al. (37). Cells were visualized using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm, and fluorescence emission at 530 nm (green) and 590 nm (red) was observed. The cationic dye JC-1 forms red fluorescent aggregates at higher potential and remains as green fluorescent monomers at lower potential. A decrease in the membrane potential is hence indicated by a shift in the fluorescence emission from red (590 nm) to green (530 nm). The data shown (green/red ratio) for each strain are from 600 individual cells, with 100 cells taken from each of six different fields. The six fields are from two individual cultures of each strain, each assayed three times.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by award 1R21AI073322 from NIH.

We are grateful to Kathleen Postle, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, for providing antibodies. We also thank Mykeshia McNorton (Dept. of Microbiology) and John Shields (Center for Advanced Ultrastructural Research), University of Georgia, Athens, for technical help with fluorescence imaging.

Footnotes

Citation Lamichhane-Khadka, R., A. Kwiatkowski, and R. J. Maier. 2010. The Hyb hydrogenase permits hydrogen-dependent respiratory growth of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. mBio 1(5):e00284-10. doi:10.1128/mBio.00284-10.

REFERENCES

- 1. Miller T. L., Wolin M. J. 1996. Bioconversion of cellulose to acetate with pure cultures of Ruminococcus albus and a hydrogen-using acetogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1589–1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maier R. J. 2003. Availability and use of molecular hydrogen as an energy substrate for Helicobacter species. Microbes Infect. 5:1159–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Russell J. B. 1998. The importance of pH in the regulation of ruminal acetate to propionate ratio and methane production in vitro. J. Dairy Sci. 81:3222–3230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marthinsen D., Fleming S. E. 1982. Excretion of breath and flatus gases by humans consuming high-fiber diets. J. Nutr. 112:1133–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levitt M. D., Hirsh P., Fetzer C. A., Sheahan M., Levine A. S. 1987. H2 excretion after ingestion of complex carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 92:383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hernot D. C., Boileau T. W., Bauer L. L., Middelbos I. S., Murphy M. R., Swanson K. S., Fahey G. C., Jr. 2009. In vitro fermentation profiles, gas production rates, and microbiota modulation as affected by certain fructans, galactooligosaccharides, and polydextrose. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57:1354–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guarner F., Malagelada J. R. 2003. Role of bacteria in experimental colitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 17:793–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maier R. J. 2005. Use of molecular hydrogen as an energy substrate by human pathogenic bacteria. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:83–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maier R. J., Olczak A., Maier S., Soni S., Gunn J. 2004. Respiratory hydrogen use by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is essential for virulence. Infect. Immun. 72:6294–6299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vignais P. M., Colbeau A. 2004. Molecular biology of microbial hydrogenases. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 6:159–188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zbell A. L., Benoit S. L., Maier R. J. 2007. Differential expression of NiFe uptake-type hydrogenase genes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology 153:3508–3516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vignais P. M., Billoud B., Meyer J. 2001. Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:455–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vignais P. M. 2007. Hydrogenases and H+-reduction in primary energy conservation . In Penefsky H., Schäfer G. Bioenergetics. Structure and function in energy-transducing systems (results and problems in cell differentiation). Springer, Berlin, Germany: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen G. N., Rickenberg H. V. 1956. Concentration specifique reversible des amino acides chez Escherichia coli. Ann. Inst. Pasteur (Paris) 91:693–720 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ballantine S. P., Boxer D. H. 1985. Nickel-containing hydrogenase isoenzymes from anaerobically grown Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 163:454–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sawers R. G., Jamieson D. J., Higgins C. F., Boxer D. H. 1986. Characterization and physiological roles of membrane-bound hydrogenase isoenzymes from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 168:398–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merberg D., O’Hara E. B., Maier R. J. 1983. Regulation of hydrogenase in Rhizobium japonicum: analysis of mutants altered in regulation by carbon substrates and oxygen. J. Bacteriol. 156:1236–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamamoto I., Ishimoto M. 1978. Hydrogen-dependent growth of Escherichia coli in anaerobic respiration and the presence of hydrogenases with different functions. J. Biochem. 84:673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehta N. S., Benoit S., Mysore J. V., Sousa R. S., Maier R. J. 2005. Helicobacter hepaticus hydrogenase mutants are deficient in hydrogen-supported amino acid uptake and in causing liver lesions in A/J mice. Infect. Immun. 73:5311–5318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Niven D. F., Hamilton W. A. 1972. The mechanism of energy coupling in the active transport of amino acids by Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. J. 127:a58P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foucaud C., Kunji E. R., Hagting A., Richard J., Konings W. N., Desmazeaud M., Poolman B. 1995. Specificity of peptide transport systems in Lactococcus lactis: evidence for a third system which transports hydrophobic di- and tripeptides. J. Bacteriol. 177:4652–4657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Driessen A. J. M., Van Leeuwen C., Konings W. N. 1989. Amino acid transport by membrane vesicles of an obligate anaerobic bacterium, Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 171:1453–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saier M. H. 2000. Families of transmembrane transporters selective for amino acids and their derivatives. Microbiology 146:1775–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gordon J. A. 1991. Use of vanadate as protein-phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitor. Methods Enzymol. 201:477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Postle K. 1993. TonB protein and energy transduction between membranes. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25:591–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Skare J. T., Ahmer M. M., Seachord C. L., Darveau R. P., Postle K. 1993. Energy transduction between membranes: TonB, a cytoplasmic membrane protein, can be chemically crosslinked in vivo to the outer membrane receptor FepA. J. Biol. Chem. 268:16302–16308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schauer K., Rodionov D. A., de Reuse H. 2008. New substrates for TonB-dependent transport: do we only see the “tip of the iceberg”? Trends Biochem. Sci. 33:330–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ollis A. A., Manning M., Held K. G., Postle K. 2009. Cytoplasmic membrane protonmotive force energizes periplasmic interactions between ExbD and TonB. Mol. Microbiol. 73:466–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zbell A. L., Maier R. J. 2009. Role of Hya hydrogenase in recycling of anaerobically produced H2 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1456–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee E., Huda M. N., Kuroda T., Mizushima T., Tsuchiya T. 2003. EfrAB, an ABC multidrug efflux pump in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3733–3738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Larsen R. A., Myers P. S., Skare J. T., Seachord C. L., Darveau R. P., Postle K. 1996. Identification of TonB homologs in the family Enterobacteriaceae and evidence for conservation of TonB-dependent energy transduction complexes. J. Bacteriol. 178:1363–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stults L. W., O’Hara E. B., Maier R. J. 1984. Nickel is a component of hydrogenase in Rhizobium japonicum. J. Bacteriol. 159:153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peng Y., Stevens P., De Vos P., De Ley J. 1987. g, NH4+ concentration and hydrogen production in cultures of Rhodobacter sulfidophilus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:1243–1247 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jovanovic G., Lloyd L. J., Stumpf M. P., Mayhew A. J., Buck M. 2006. Induction and function of the phage shock protein extracytoplasmic stress response in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 281:21147–21161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glaser P., Sharpe M. E., Raether B., Perego M., Ohlsen K., Errington J. 1997. Dynamic, mitotic-like behavior of a bacterial protein required for accurate chromosome partitioning. Genes Dev. 11:1160–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]