Abstract

Estrogen is an important protective factor against obesity in females. Therefore, postmenopausal women have a higher rate of obesity than premenopausal women, which is associated with age-related loss of ovary function. It has been reported that a diet containing conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) reduced body weight and body fat mass in the animal model as well as in human trials. We hypothesized that ingestion of CLA would reduce body weight gain in ovariectomized (OVX) female C57BL/6J mice which is a model for postmenopaual women. We further hypothesized that body weight reduction may improve obesity-related complication. To test this hypothesis, the OVX mice fed with a high fat diet containing CLA for 3 months. Mice had significantly reduced body weight gain compared to OVX mice fed with a high fat diet without CLA. While CLA was effective in slowing down of body weight gain of both Sham and OVX mice, analysis of adipocyte size and number suggested different mechanisms for loss of fat tissue in these two groups of mice. CLA treatment did not increase liver weight and accumulation of fat in the livers of OVX mice. Furthermore, CLA intake did not change insulin resistance. Our results indicate that CLA is functional as an anti-obesity supplement in the mouse model for postmenopausal women, and the anti-obesity effect of CLA is not estrogen-related.

Keywords/phrases: Conjugated Linoleic Acids, Obesity, Fatty liver, Mice, Ovariectomy, Postmenopause

1. Introduction

Estrogen is an important protective factor against obesity in the female [1], therefore the overall rate of obesity and related metabolic complications is higher in postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women [2]. Obesity is a major contributing factor to metabolic syndrome including increased body fat, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, elevated blood pressure and increased cardiovascular disease [2]. There are large populations of postmenopausal women suffering from these obesity-related issues due to the intake of today's western diet [3] [4]. Since weight gain is a health concern in postmenopausal women, it is important to evaluate the effects of dietary and pharmaceutical approach to the prevention and treatment of obesity in postmenopausal women. Conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs) are one class of polyunsaturated fatty acids. When consumed in proper quantities, CLAs are associated with a variety of health benefits. The most abundant isomer of CLAs is the cis-9/trans-11 form in ruminant meat and dairy products, which displays anti-arthrosclerosis effects. Moreover, cis-9/trans-11 CLA exhibits an anti-aromatase activity, resulting in the reduction of estrogen levels and resulted suppression of the proliferation of hormone-dependent breast cancer cells [5]. The CLA isomer shown to reduce body weight and body fat mass is trans-10/cis-12 [6-8]. The chemically synthesized CLA mixtures, containing equal amounts of cis-9/trans-11 and trans-10/cis-12 forms, are commonly used as a diet supplement. It has been reported that a diet consisting of these CLA isomers reduced body weight and body fat mass in animal model and human trials [9]. Because these CLA mixtures are commercially available, CLA intake is thought to be a logical approach to prevent obesity and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Moreover, the key approach for diabetes mellitus is weight loss that would improve insulin resistance [10]. Therefore, the inhibition of body weight gain in response to CLA supplements may also improve insulin resistance in postmenopausal women.

The reported clinical problems associated with CLA use include the induction of fatty liver, and the enhancement of the fatty acid synthesis pathway in liver [7, 11]. It has been shown that circulating levels of estrogen within the physiological range may provide a protective effect on liver fat accumulation in women [12]. Therefore, postmenopausal women may have a higher risk of developing fatty liver due to lower levels of circulating estrogens and the intake of CLA supplements. As estrogen has a protective effect against fatty liver, the anti-aromatase effect of CLA may have an additional impact on the development of fatty liver in postmenopausal women. Thus, effects of CLA intake on liver as well as obesity in postmenopausal women should be carefully evaluated.

Currently, little information is available on the exact mechanism of CLA in low estrogen conditions. There are currently no model studies that focus on the effect of CLAs, side effects and their molecular action in postmenopausal women. The ovariectomized (OVX) mouse model is established to mimic menopausal women and study the impact triggered from the loss of ovary function [4]. Withdrawal of estrogen after bilateral ovariectomy in rodents causes increased food intake and decreased energy expenditure, resulting in obesity [4]. Additionally, this obesity phenotype leads to metabolic complications, in particular insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis under a high fat diet.

The objective of this research is to gain insight on the efficacy of CLA against obesity and obesity-related complications in postmenopausal women using the mouse model. We hypothesized that ingestion of CLA would reduce body weight gain in OVX female C57BL/6J mice. To test our hypothesis, we fed OVX mice with a CLA diet and examined body weight changes. In addition, the adipocyte size, number, glucose metabolism and liver-associated side effects were examined.

2. Methods and materials

2-1. Ingredient composition of diets

A mixture of CLAs (trans-10/cis-12 and cis-9/trans-11 isomers) was provided by Nu-Check Prep Inc (Elysian, MN). The percentages of the each of the isomers were the following: 40-45% for trans-10/cis-12 isomer and 40% for cis-9/trans-11 isomer. Diets were obtained from Research Diet (New Brunswick, NJ). The ingredient compositions of diets are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Composition of the experimental diets.

| Ingredient | HF | HF-CLA |

|---|---|---|

| g/kg | ||

| Casein, 30 Mesh | 200 | 200 |

| L-Cystine | 3 | 3 |

| Corn Starch | 224 | 224 |

| Maltodextrin 10 | 132 | 132 |

| Sucrose | 100 | 100 |

| Cellulose, BW200 | 50 | 50 |

| Soybean Oil | 70 | 70 |

| Lard | 173 | 173 |

| t-Butylhydroquinone | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Mineral Mix S10022G | 35 | 35 |

| Vitamin Mix V10037 | 10 | 10 |

| Choline Bitartrate | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| CLA | 0 | 10 |

CLA was mixed to a modified AIN-93G diet enriched in fat (HF).

2-2.Animals

All animal research procedures were approved by the City of Hope IACUC committee and were in accordance with NIH guidelines. Breeding stock strain C57Bl/6J was obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All animals were housed at the City of Hope Animal Resources Center in ventilated cage racks, had free access to water and were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle.

2-3. Experimental design

At 3 weeks old, female mice were weaned and maintained with 4 mice per cage. When the mice became 7 weeks old, they were divided into 2 groups (n=20). One group underwent Sham operations (Sham), while the other group had dorsal ovariectomies (OVX) under general anesthesia. One week after the surgery, all mice were started on a 45% high fat diet (HFD). At 20 weeks old, each group was further divided into 2 experimental groups. One group continued to feed on the HFD while another group was given HFD with 1% CLAs over 3 months (i.e., four experimental groups: Sham HFD, Sham HFD+CLA, OVX HFD and OVX HFD+CLA). Body weight was recorded once a week. For food intake measurement, mice were individually housed with food and water ad libitum. Food consumption was measured during a 4-day period at 33 weeks old.

2-4. Glucose tolerance test

At 18 and 30 weeks of age, the fasting basal glucose levels of mice were measured, and then glucose tolerance tests were performed. The mice were fasted with free access to drinking water for 18 hours prior to the test period. Baseline glucose levels were recorded for each mouse. The mice were then challenged with 1.5mg glucose/gram [D-(+)-Glucose anhydrous, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO] body weight glucose load. The glucose levels pre, 30, 60, 120 and 180 min post injection were measured using a glucometer (Bayer, Germany).

2-5. Pathological analysis

Liver, uterus, inguinal and gonadal fat pads were harvested from mice and the wet weights were measured at the end of the experiment (at 224 days of age). The tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Five-micrometer sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined by light microscope.

2-6. Adipocyte cell number analysis

The relative adipocyte cell number was estimated using DNA content from 100 mg tissue. The genomic DNA was isolated from adipose tissue samples after proteinase K digestion, by means of isopropanol precipitation [13]. Briefly, 100 mg adipose tissues were lysed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer [100mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 5mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS, 200mM NaCl, 100 μg proteinase K/ml] and incubated at 55°C with agitation for 5 hours. One volume of isopropanol was added to the lysate, and samples were mixed or swirled until precipitation was completed. Precipitated DNA was recovered and resuspended in 50 μl of 10mM Tris-HCl containing 0.1 mM EDTA. DNA concentration was measured using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

2-7. Adipocyte size analysis

The adipocyte size distribution was determined by analyzing 2 representative areas on each fat cell tissue sample, using a microscope (Nikon, eclipse TE 2000-S, Japan). The images were obtained using software (Meta imaging series, Downingtown, PA). The size of an individual fat cell was calculated by measuring the long (a) and the short (b) cross section of each fat cell using Meta imaging software for image analysis and applying the formula used to calculate the area of an ellipse (area = a*b* π/4) using MS excel.

2-8. Statistical analyses

All results are reported and depicted as means ± SE, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05. Twenty observations in each group were made comparing Sham and OVX mice for body weight, serum glucose and liver weight. t test was performed to test group differences between Sham and OVX mice. Ten observations in each group were made, unless otherwise indicated, comparing 2 groups (HFD and HFD+CLA) in each Sham or OVX mice for body weight, organ weight, adipocyte number and size. t test was performed to test group differences between HFD and HFD+CLA groups. Data sets were analyzed for statistical significance using Prism GraphPad 4 software.

3. Results

3-1. Characterization of the mouse model

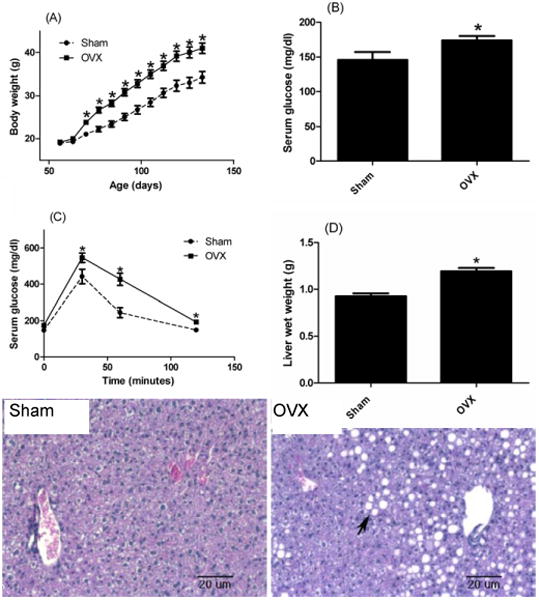

To establish a mouse model for postmenopausal woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hepatic steatosis, we ovariectomized 7-week-old female mice to reduce estrogen levels; one week later, the HFD was started to induced obesity. The Sham operation was performed as a control. Additional body weight gain was seen after ovariectomy in C57BL/6 mice compared to the Sham operation mice after 70 days of age (Figure 1A). There were significant differences in fasting serum glucose levels (Figure 1B) when they became 130 days old. Moreover, blood glucose levels of OVX mice were significantly greater than those of Sham mice at 30 and 60 minute time points after glucose injection (Figure 1C). The OVX mice showed obesity and obesity-related impaired glucose tolerance. Moreover, OVX mice had significantly greater liver wet weights and more fat accumulation in the liver compared to the Sham mice (Figure 1D and E).

Fig. 1.

Body weight change after operation (sham or ovariectomy) in Sham (circle) and OVX (square) mice (A). Measurement of basal glucose level (B) and glucose tolerance test (C) were performed when mice were 18 weeks old. (D) Representative pictures of H&E staining of livers at 18 weeks-old. Note the accumulation of large lipid droplets in livers of OVX mice (arrow). Results correspond to the means ± SE (t-test). n=20 (A), n=10 (B, C and D). *, P<0.05 Sham vs. OVX.

3-2. Measurements of body weight and food intake

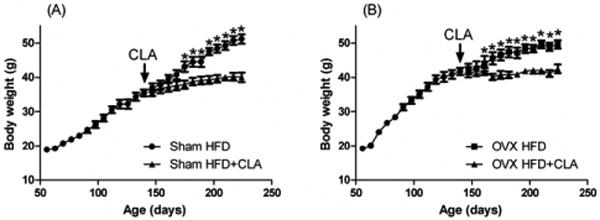

The HFD+CLA fed group had significantly lower body weights than the control group fed with high fat diet in both Sham (-11.1g) and OVX (-7.0g) mice (Figures 2A and 2B). There were no significant differences between Sham and OVX mice in HFD group (51.1g± 1.3g and 49.5± 3.2g, respectively) at the end of experiment. However, during growth phase, OVX mice gained body weight significantly faster than the Sham mice in both diet groups. At approximately body weight of 50 g, the OVX mice stopped gaining weight, and the Sham mice eventually caught up and reached a final weight of 50g as well. CLA inhibited body weight in both groups to no more than 40 g. There were no significant differences between Sham and OVX groups in HFD+CLA groups (40.4g± 1.3g and 42.5± 3.1g, respectively) at the end of experiment. The daily food intakes of the four groups were comparable [3.43±0.21g (Sham HFD), 3.37±0.17g (Sham HFD+CLA), 3.50±0.16g (OVX HFD), 3.57±0.20g (OVX HFD+CLA), P>0.05].

Fig.2.

Body weight change before and after CLA treatment in Sham (A) and OVX (B) mice (HFD: circle, HFD+CLA: triangles) after CLA treatment at age of 140 days. Results correspond to the means ± SE (t-test). n=10 *, P<0.05 HFD vs. HFD+CLA.

3-3. White adipose tissue weight analysis

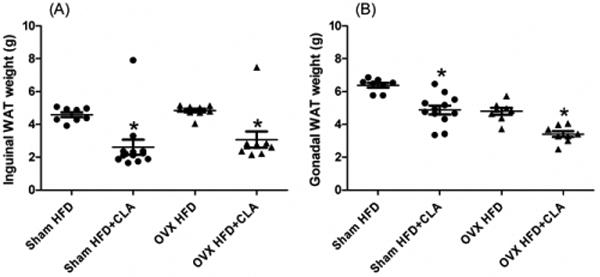

The inguinal and gonadal white adipose tissue weights in the Sham mice fed with HFD+CLA were 41% and 31% lower compared to those fed with HFD. In the OVX mice, HFD+CLA diet group had a decrease of 44% and 32% for the inguinal and gonadal white adipose tissue compared to the HFD group (Figure 3). CLA showed a greater effect on the inguinal adipose tissue in the Sham mice compared to the OVX mice. We could see a similar inhibition for gonadal adipose tissue in both Sham and OVX mice. In comparing the different fat tissues, the HFD+CLA group inhibited inguinal adipose tissue rather than gonadal adipose tissue growth in both Sham and OVX mice.

Fig. 3.

Weight of inguinal (A) and gonadal (B) white adipose tissue (Sham: circle, OVX: triangles). The samples were collected at the end of the experiment, 3 months after CLA treatment began at age 244 days. Results correspond to the means ± SE (t-test). n=8-10, *, P<0.05 HFD vs. HFD+CLA.

3-4. Adipocyte size analysis

There was significant reduction in adipocyte size in the inguinal and gonadal tissue samples of the Sham mice (Table 2) as a result of the CLA containing diet. While we also found a significant size reduction in the inguinal tissue samples of the OVX mice, no significant change in cell size was observed in the gonadal tissue samples of the OVX mice (Table 2).

Table 2. Average adipocyte area (μm2).

| Tissue Sample | HFD | HFD+CLA | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham Inguinal | 4757±108 | 3775±89 | <0.05 |

| OVX Inguinal | 4728±143 | 3964±108 | <0.05 |

| Sham Gonadal | 6161±159 | 4213±123 | <0.05 |

| OVX Gonadal | 6083±219 | 6053±176 | 0.4715 |

Results are means ± SE (t-test).

n=8-10, *, P<0.05 HFD vs. HFD+CLA

3-5. Adipocyte number measurement

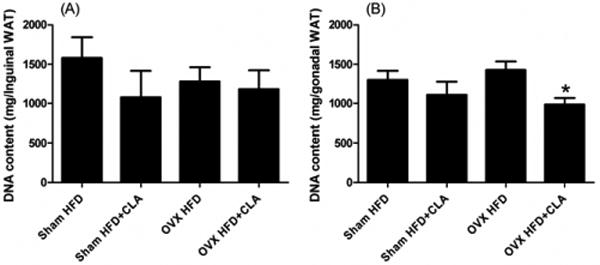

CLA diet significantly decreased adipocyte number in the gonadal adipose tissue of the HFD+CLA group compared to the HFD group in OVX mice (Figure 4 A and B). There were no significant differences in adipocyte number between the remaining groups.

Fig.4.

DNA content of inguinal (A) and gonadal (B) white adipose tissue. The samples were collected at the end of the experiment, 3 months after CLA treatment began at age 244 days. Results correspond to the means ± SE (t-test). n=8-10, *, P<0.05 HFD vs. HFD+CLA.

3-6. Uterine weight measurement

As confirmation of successful OVX-induced suppression of endogenous estrogen levels, uterine weight was measured. Weight was significantly decreased in the OVX mice compared with the Sham mice. At an age of 224 days, uteri of HFD group in Sham mice weighed 0.13±0.02g, whereas the HFD mice in OVX group weighed significantly less at only 0.04±0.0002g. There are significant differences between Sham and OVX uteri in HFD+CLA groups, 0.11±0.02g (Sham) or 0.04±0.0008g (OVX), respectively. There are no differences between the HFD and the HFD+CLA groups in either Sham or OVX mice.

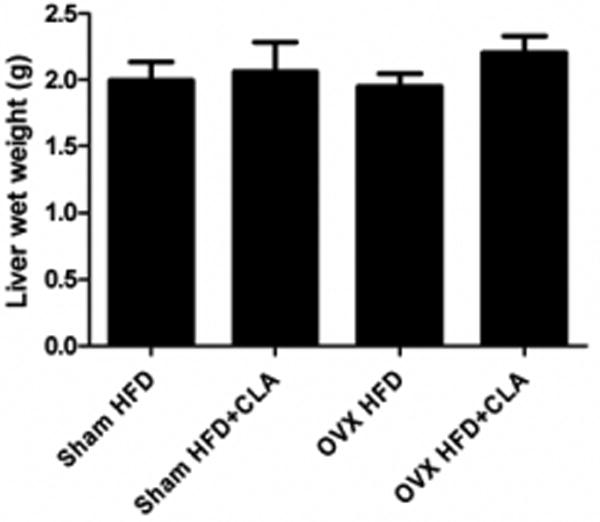

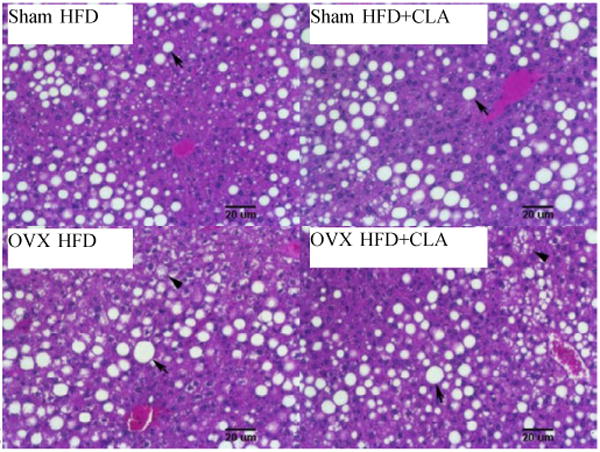

3-7. Liver weight and pathological examination

There are not significant differences between the liver weight of the HFD and the HFD+CLA groups in either the Sham or OVX mice (Figure 5). Pathological analysis showed macrosteatosis which was large fat accumulation between the central and portal vein area in Sham and OVX mice. In OVX mice, microsteatosis was also shown in the liver. CLA treatment did not increase fat accumulation in the liver in Sham or OVX mice (Figure 6).

Fig.5.

Liver wet weight with CLA and without CLA treatment in sham and OVX mice. The samples were collected at the end of the experiment, 3 months after CLA treatment began at age 244 days. Results correspond to the means ± SE (t-test). n=8-10, *, P<0.0 5HFD vs. HFD+CLA.

Fig.6.

Representative pictures of H&E staining of livers after CLA treatment. Note macrosteatosis which was large fat accumulation between the central and portal vein area in Sham and OVX mice (arrow). Microsteatosis was shown in the liver of OVX mice (arrow head).

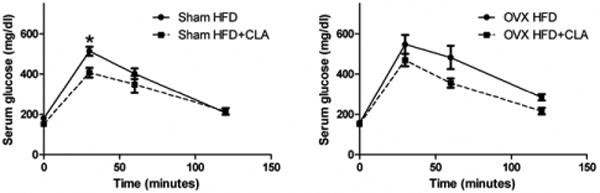

3-8. Blood glucose levels and glucose tolerance test

Serum glucose levels were lower in mice fed with HFD+CLA compared to mice fed with HFD in both Sham and OVX mice. Compared to the HFD+CLA group in Sham mice, only blood glucose levels at the 30 minute time point after glucose injection were significantly lower than in the HFD group in Sham mice. There are no significant differences in glucose levels between the HFD and HFD+CLA groups in OVX mice (Figure 6).

4. Discussion

We had hypothesized that ingestion of CLA reduces body weight gain in OVX female C57BL/6J mice. Our hypothesis is supported by the observation that CLA supplement inhibited body weight gain in both the Sham and OVX mice in our mouse model. The major finding of the present investigation is that CLA has an anti-obesity effect in mice independent of estrogen levels. These results correspond to a recent report that CLA improves BMI in postmenopausal women [14] who have lower estrogen levels compared to pre-menopausal women. As reported, CLA targeted genes [7, 15] are not estrogen regulated genes. This could explain that CLA reduces body weight in OVX mice in a similar manner to the Sham mice. It has been reported that the percentage of CLA in diet greater than 0.5% was required to achieve suppression of body fat in mouse model. Most studies used 1% CLA to evaluate the biological activity of CLA [16, 17]. Thus, 1% CLA was used in this study. Moreover, the dose used in our study is equivalent to the human dose used for clinical trials [14] in postmenopausal women, according to calculations based on body surface area (approximately 6.5 g CLA/ day) [18].

The effect of CLA on adipose tissue for different parts of the body in OVX mice were assessed by the weight changes of adipose tissues. The deleterious effects of estrogen deficiency in increasing adipose tissue in postmenopausal women have been related to distribution of fat mass in the abdominal rather than in the subcutaneous areas [1]. The reduction of abdominal fat pads such as the gonadal fat pad is important, because the risk for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, some types of cancer and metabolic disorder correlates more to the central (abdominal) distribution of fat than the amount of total body fat [19]. Our results showed that CLA reduced the inguinal fat pads more effectively than the gonadal in both Sham and OVX mice, even though significant reduction of the gonadal fat pads was also observed. These results also correlate with clinical studies, which show there is no region-specific reduction of adipose tissue in obese postmenopausal women [14].

Additionally, to evaluate CLA's molecular mechanism in slowing down body weight gain, the changes of adipocyte size and number were analyzed. Several studies in animal model have showed that the major factor for reduction of fat mass by CLA is decreased adipocyte size, rather than a reduction in their numbers in adult stage [6]. Our results showed that the impact of CLA on cell number was not as strong as on cell size; the cell size seems to correlate better to fat weight in both Sham and OVX mice. Only the gonadal fat pads in the OVX mice showed a significant change in cell number after CLA treatment. These results suggest that different locations of fat tissues are regulated differently by CLA in terms of cell size and number. These results also imply that there are different regulation mechanisms between Sham and OVX mice, although weight reduction has been seen in all groups.

Postmenopausal women have a higher risk of developing fatty liver due to lower levels of circulating estrogen [12]. The trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer has been reported to reduce obesity in mice and other animals [6, 7]; however, other reports showed trans-10,cis-12 CLA may cause undesirable effects, such as fatty liver through the modification of fatty acid synthesis pathway in liver [20, 21]. As postmenopausal women have potential problems for fat accumulation in the liver, it is important to monitor the side effects of CLA for liver. Our results showed that the low estrogen status did not have an impact on the CLA effect for liver fat accumulation. Such results agree with clinical trial findings that two markers of hepatic function, alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) (which are linked to the level of liver fat content) were unchanged in postmenopausal women consuming CLA [14].

We also evaluated whether CLA treatment could improve insulin resistance, one of the obesity-related clinical complications. Our results showed that CLA treatment did not significantly change glucose metabolism in OVX mice even the body weight gain were significantly inhibited. CLA had the effect of lowering BMI during the last 8 weeks of each 16-week diet period in postmenopausal woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus [14]. However, it had no significant effect on fasting glucose or insulin levels. It reported that the healthy postmenopausal women with largest waists had a significantly greater serum insulin concentration in the CLA-mix (cis-9/ trans-11 and trans10/cis12- CLA) group than control. However, the CLA supplements did not affect in the leaner women [22]. Thus, further observation will be needed to evaluate insulin desensitizing effect of CLA in obese postmenopausal women.

The limitation of this study is that ovariectomized mice do not have the exact hormone condition as postmenopausal women. It has been reported that postmenopausal ovary can produce androgen [23]. With reduction of estrogen, there is a shift to androgen dominant, leading to metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women [24]. Postmenopausal mouse model has been developed using chemical 4-vinylcyclohexene (VCD) [25]. It is thought that ovaries of VCD-induced mice produce less estrogen and continue to produce androgen, it is mimicking the hormonal condition of postmenopausal women. Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm our results using another mouse model such as VCD mice, moreover to investigate the mechanism of CLA in postmenopausal women.

In summary, the high fat diet with 1% CLA reduced body weight gain in both the Sham and OVX mice compared to control HFD only groups. While CLA effectively slowed down body weight gain of both Sham and OVX mice, analysis of adipocyte size and number suggested that different regulatory pathways were involved in the loss of fat tissue in these two groups of mice. CLA treatment did not increase liver weight or accumulation of fat in the livers of the OVX mice. The inhibition of body weight gain was seen in OVX mice treated with CLA; however, CLA did not improve insulin resistance. Our results indicate that CLA is functional as an anti-obesity supplement in the mouse model for postmenopausal women, and the anti-obesity effect of CLA is not estrogen-related.

Fig.7.

Blood glucose concentrations in Sham and OVX mice after glucose challenge. Glucose tolerance test was performed when mice were 30 weeks old. Results correspond to the means ± SE (t-test). n=8-10, *, P<0.05 HFD vs. HFD+CLA.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01 ES08258.

Abbreviations

- CLA

Conjugated linoleic acid

- HFD

High fat diet

- OVX

Ovariectomized

- WAT

White adipose tissue

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cooke PS, Naaz A. Role of estrogens in adipocyte development and function. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:1127–35. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobo RA. Metabolic syndrome after menopause and the role of hormones. Maturitas. 2008;60:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. Jama. 2006;295:1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers NH, Perfield JW, 2nd, Strissel KJ, Obin MS, Greenberg AS. Reduced energy expenditure and increased inflammation are early events in the development of ovariectomy-induced obesity. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2161–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S, Oh SR, Phung S, Hur G, Ye JJ, Kwok SL, Shrode GE, Belury M, Adams LS, Williams D. Anti-aromatase activity of phytochemicals in white button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) Cancer Res. 2006;66:12026–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domeneghini C, Di Giancamillo A, Corino C. Conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs) and white adipose tissue: how both in vitro and in vivo studies tell the story of a relationship. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:663–72. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silveira MB, Carraro R, Monereo S, Tebar J. Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:1181–6. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churruca I, Fernandez-Quintela A, Portillo MP. Conjugated linoleic acid isomers: differences in metabolism and biological effects. Biofactors. 2009;35:105–11. doi: 10.1002/biof.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plourde M, Jew S, Cunnane SC, Jones PJ. Conjugated linoleic acids: why the discrepancy between animal and human studies? Nutr Rev. 2008;66:415–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad F, Considine RV, Bauer TL, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, Goldstein BJ. Improved sensitivity to insulin in obese subjects following weight loss is accompanied by reduced protein-tyrosine phosphatases in adipose tissue. Metabolism. 1997;46:1140–5. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pariza MW. Perspective on the safety and effectiveness of conjugated linoleic acid. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:1132S–1136S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1132S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki A, Abdelmalek MF. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2009;5:191–203. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laird PW, Zijderveld A, Linders K, Rudnicki MA, Jaenisch R, Berns A. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris LE, Collene AL, Asp ML, Hsu JC, Liu LF, Richardson JR, Li D, Bell D, Osei K, Jackson RD, Belury MA. Comparison of dietary conjugated linoleic acid with safflower oil on body composition in obese postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaRosa PC, Miner J, Xia Y, Zhou Y, Kachman S, Fromm ME. Trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid causes inflammation and delipidation of white adipose tissue in mice: a microarray and histological analysis. Physiol Genomics. 2006;27:282–94. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00076.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon HS, Lee HG, Seo JH, Chung CS, Kim TG, Choi YJ, Cho CS. Antiobesity effect of PEGylated conjugated linoleic acid on high-fat diet-induced obese C57BL/6J (ob/ob) mice: attenuation of insulin resistance and enhancement of antioxidant defenses. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20:187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLany JP, Blohm F, Truett AA, Scimeca JA, West DB. Conjugated linoleic acid rapidly reduces body fat content in mice without affecting energy intake. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1172–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.4.R1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. Faseb J. 2008;22:659–61. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vona-Davis L, Howard-McNatt M, Rose DP. Adiposity, type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome in breast cancer. Obes Rev. 2007;8:395–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clement L, Poirier H, Niot I, Bocher V, Guerre-Millo M, Krief S, Staels B, Besnard P. Dietary trans-10,cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid induces hyperinsulinemia and fatty liver in the mouse. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1400–9. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m20008-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guillen N, Navarro MA, Arnal C, Noone E, Arbones-Mainar JM, Acin S, Surra JC, Muniesa P, Roche HM, Osada J. Microarray analysis of hepatic gene expression identifies new genes involved in steatotic liver. Physiol Genomics. 2009;37:187–98. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90339.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raff M, Tholstrup T, Toubro S, Bruun JM, Lund P, Straarup EM, Christensen R, Sandberg MB, Mandrup S. Conjugated linoleic acids reduce body fat in healthy postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2009;139:1347–52. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burger HG. Androgen production in women. Fertil Steril. 2002;77 4:S3–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen I, Powell LH, Crawford S, Lasley B, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Menopause and the metabolic syndrome: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1568–75. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero-Aleshire MJ, Diamond-Stanic MK, Hasty AH, Hoyer PB, Brooks HL. Loss of ovarian function in the VCD mouse-model of menopause leads to insulin resistance and a rapid progression into the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R587–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90762.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]