Abstract

Objectives

Family-based association tests such as the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) are dependent on the successful ascertainment of true nuclear family trios. Relationship misspecification inevitably occurs in a proportion of trios collected for genotyping which undetected can lead to a loss of power and increased Type I error due to biases in over-transmission of common alleles. Here, we introduce a method for evaluating the authenticity of nuclear family trios.

Methods

Operating in a Bayesian framework, our approach assesses the extent of pedigree inconsistent genotype configurations in the presence of genotyping errors. Unlike other approaches, our method: (i) utilizes information from three individuals collectively (the whole trio) rather than consider two independent pairwise relationships; (ii) down-weighs SNPs with poor performance; (iii) does not require the user to pre-define a rate of genotyping error, which is often unknown to the user and seldom fixed across the different SNPs considered which available methods unrealistically assumed.

Results

Simulation studies and comparisons with a real set of data showed that our approach is more likely to correctly identify the presence of true and misspecified trios compared to available software, accurately infers the extent of relationship misspecification in a trio and accurately estimates the genotyping error rates.

Conclusions

Assessing relationship misspecification depends on the fidelity of the genotype data used. Available algorithms are not optimised for genotyping technology with varying rates of errors across the markers. Through our comparison studies, our approach is shown to outperform available methods for assessing relationship misspecifications.

Keywords: relationship misspecification, pedigree inconsistency, genotyping error

1. INTRODUCTION

The field of population genetics is in an era where genome-wide scans for association with common diseases and complex traits are realistically possible and a number of such studies have recently been completed and published (for example, the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium [1]). These have primarily made use of case-control designs since the relative ease with which unrelated affected individuals and controls are available is a clear advantage over experimental designs involving family trios and sib-pairs, where admission criteria are typically stringent and difficult to satisfy. However, one main disadvantage of case-control study designs is the vulnerability to effects of confounding, brought by the presence of undetected or unaccounted population structure [2-6]. Thus for disease traits where recruitment of pedigree data on a large scale is possible, the use of family-based pedigrees avoids the pitfalls associated with the presence of population structure in a case-control association study.

Family-based association studies are important tools in our efforts to define the genetic basis of common disease [7]. However, relationship misspecification is a common problem among samples collected for family studies and undetected pedigree errors can significantly affect association statistics. While several methods have been proposed for detecting relationship misspecification, these generally work well when large amounts of genetic data are available. In candidate gene studies or during the initial stages of sample selection for a whole genome association analysis, investigators may only have sparse sets of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) genotypes, which available methods are not optimized for.

A wide range of association tests based on family studies have been proposed [8-14] and these tests typically require genotyping data from an affected individual and their biological parents (a nuclear family trio). Here we consider the widely used transmission disequilibrium test (TDT). The TDT is appealing because of its relative simplicity and like other family-based association tests has the advantage of being robust to the effects population stratification [15].

Family-based association tests, such as the TDT, are dependent on the successful ascertainment of true nuclear family trios. However relationship misspecification, from a variety of origins, will inevitably occur in trios collected for genotyping. One common source of misspecification is undisclosed paternal discrepancy. A review of 17 populations, each studied for reasons other than disputed paternity, reported a median rate of paternal discrepancy of 3.7% (inter-quartile range was 2.0% to 9.6%) [16]. Low socio-economic status, deprivation and young maternal age are associated with higher rates of this form of misspecification [17]. The situation can be further complicated by a number of other reasons: local customs, where relatives contribute in caring for children in extended families; study design, where retrospective collection of parental DNA samples may increase the likelihood of relationship misspecification; communication problems between researchers and participants; and laboratory or clinician sample handling error resulting in DNA swapping.

Undetected relationship misspecifications, like other sources of genotyping errors, can lead to a loss of power [18] and increased Type I error due to a bias in over-transmission of common alleles [19-20] (see also Figure 1). In a review of 79 significant TDT-derived associations between microsatellite markers and disease, the most-common alleles exhibited transmission distortion in 31 studies, 27 of which were over-transmission of the most-common allele [20]. TDT variants that are robust to genotyping error have been proposed [21,22] but it seems reasonable to remove misspecified nuclear family trios if they can be detected. Unfortunately relationship misspecifications can be difficult to assess when limited numbers of markers are typed [23] (Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials), particularly in the presence of an unknown background rate of genotyping error, and when a range of misspecification types are present.

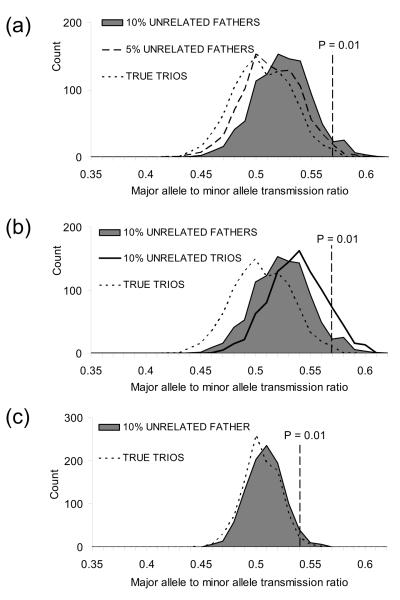

Fig. 1.

Relationship misspecification and over-transmission of common alleles in TDT, simulated with minor allele frequencies of 0.1 in (a) and (b), and 0.4 in (c). The figures investigate the relation between over-transmission bias and: (a) the proportion of pedigrees that are misspecified (5% versus 10% misspecified fathers); (b) the severity of misspecification (misspecified father versus both parents misspecified); (c) allele frequency differences. A bias towards over-transmission of common alleles in TDT in the presence of genotyping error is well-recognized (Heath 1998, Mitchell et al. 2003). The error models considered in previous reports have generally been random errors consistent with imperfect genotyping technologies, rather than the clustered errors one would expect to see as a result of relationship misspecification. Here we demonstrate that relationship misspecification produces a similar bias. Using the SimPed application (Leal et al. 2005), we simulated a neutral SNP marker in a sample of 1000 nuclear family trios, the majority of trios were true parent-offspring trios and no genotyping error was simulated. Each dataset contained a known rate of disguised misspecification (0%, 5% or 10% trios of the 1000 trios) and different misspecification types (Unrelated fathers = trios with an unrelated male disguised as a father; Unrelated trios = three unrelated individuals disguised as a nuclear family trio); and two allele frequencies. Each simulation was repeated 1000 times, and the proportion of major allele transmissions plotted. The transmission ratio equivalent to a TDT p-value of 0.01 is marked on each histogram. When SNP alleles are almost equal in frequency (i.e. a frequency of 0.5), less transmission bias is observed.

There are a wide range of statistical techniques and software available to assess relationships between individuals using genetic markers [24-30], which have been discussed in two reviews by Blouin [31], and Jones and Arden [32]. The methods are generally designed to utilize large numbers of multi-allelic genetic markers such as microsatellites, but can also be applied to SNP data. Most of these approaches take a likelihood perspective and compare a number of pre-specified relationships within a likelihood ratio framework in order to infer the most likely relationship given the observed genetic data. However, there are a number of disadvantages with existing methods: (i) the inability to realistically model the presence of genotyping errors - recent methods allow and account for the presence of genotyping errors by assuming a constant user-defined error rate which is fixed across all the markers, in reality individual SNP markers perform with different rates of success which users are often unable to quantify accurately; (ii) evaluating pairwise relationships rather than analyzing the complete information from a trio - most available approaches do not evaluate the authenticity of a trio within a single analytical framework and instead decompose the trio relationship into three pairwise relationships which are each assessed independently (except for the method introduced by Sieberts and colleagues [29]); (iii) assessing the degree of kinship using the extent of allele sharing - these metrics can be distorted when markers are associated with the disease. Thus existing methods work well when genotype data from large numbers of unlinked neutral multi-allelic markers are available. However, these methods may not be optimized for detecting misspecified nuclear family trios in the presence of limited datasets where the SNPs genotyped are often located in genes putatively associated with the trait of interest.

In general, there are three scenarios that can affect a nuclear family trio: paternal misspecification, maternal misspecification or misspecification of both parents. When one or more relationship is misspecified, configuration of genotypes which are inconsistent with mendelian transmission can occur for the putative parents and offspring trio. For a biallelic SNP, there are a total of 27 possible genotype combinations for parents and offspring, of which 15 are consistent with mendelian transmission and 12 are not (Figure 2). In the absence of genotyping errors (or rarer causes, such as mutations or the presence of copy number variants), the observation of a single mendelian error would provide absolute evidence for a relationship misspecification. In practice, errors due to genotyping can occur and these can often result in genotype configurations which are inconsistent with mendelian transmission. Based on these simple insights, we propose a method to assess the authenticity of nuclear family trios by investigating the occurrences of genotype configurations that are inconsistent with mendelian transmission in a trio, where any observed inconsistencies are likely to be attributed to either genotyping errors, or a misspecification of at least one parent-offspring relationship, or both.

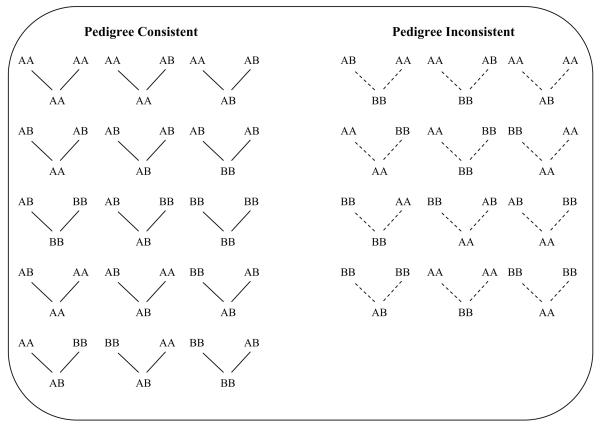

Fig. 2.

The 27 possible genotype configurations for genotype data at a SNP for three individuals (a trio). The two alleles for the SNP have been generically defined as A and B. Each set of trio is arranged such that the putative parents are joined to the putative offspring by the two lines, where solid lines indicate that the observed genotypes are consistent with mendelian transmission and dotted lines indicate that the observed genotypes are inconsistent with mendelian transmission.

In assessing trios, it is often convenient and intuitive to interpret posterior probabilities for specified relationships compared to significances (p-values) from likelihood-based test statistics which rely on assumptions from asymptotic distributions. In this paper, we propose a conceptually simple method for evaluating the authenticity of trios using SNP information in a Bayesian setting that assesses the extent of pedigree inconsistencies in the presence of genotyping errors. Simply put, nuclear family trios which possess greater extent of pedigree inconsistent genotypes are more likely to be false compared to those with almost no pedigree inconsistencies. Our method allows for differential rates of genotyping errors across the SNPs, and down-weighs SNPs with poor performance. Evaluated within a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) framework, the method naturally estimates the allele frequencies for each SNP and the posterior probabilities for four possible scenarios: true nuclear family trios (no misspecification), three unrelated individuals (misspecification of both parents), unrelated paternal and unrelated maternal trio (single parent misspecification).

We compare our proposed method against a range of currently available software packages for assessing pedigree relationship with a series of simulation studies. We also apply our method to identify misspecified trios in the early stages of a genome-wide scan of malaria susceptibility (http://www.malariagen.net). The algorithm described in this paper has been implemented in Nucl3ar, which is available upon request from the authors.

2. METHODS

Suppose there are n trios and every individual in each trio is genotyped at L biallelic loci. We assume a model where every trio must belong to one of the four possible mutually exclusive categories: (1) true trio; (2) both parents misspecified trio; (3) misspecified-father trio; (4) misspecified-mother trio. Let Z denote the (unknown) status of the trios, and is a vector of length n, with the ith entry zi ε {1, 2, 3, 4}, where the four number states correspond to the above specified relationships respectively. Let E, F and W denote the vectors of genotyping error rates, minor allele frequencies and the weights of the L loci respectively, with elements el, fl and wl for SNP l, where l = 1, 2, … , L. We denote M as a n × L binary matrix where the (i, l) entry, mil, takes value one only if a pedigree inconsistent genotype configuration is observed in pedigree i at SNP l, and is zero otherwise. Similarly, denote G as the n × L binary matrix where the (i, l) entry, gil, takes value one only if there is a genotyping error for one of the individuals in pedigree i at SNP l, and is zero otherwise. This implicitly assumes the occurrence of genotyping errors within a trio to be a Poisson process, where the probability of observing more than one genotyping error in each trio is negligible. Let P be the n × 4 matrix of probabilities such that the (i, j) entry, pij, measures the probability that pedigree i is assigned to relationship j.

Conditional on a false trio relationship, the trio must either have misspecified both parents, or have misspecified one of the parents. We use a Dirichlet (𝒟) prior to model pi = (pi1, pi2, pi3, pi4) such that

where λis are chosen based on prior beliefs.

In the absence of any genetic or epidemiological information, we can assume that it is equally likely for a relationship to be either true or false. This is modeled by the constraint that . In our analyses, we have assumed that the expected prior probability of a single misspecified parent-offspring relationship is three times more likely than a complete misspecification of the trio relationship (misspecified parents), and it is equally likely to be either of the two single misspecified parent-offspring relationship. Under these assumptions, we have chosen λ1 = 50, λ2 = 50/7, λ3 = λ4 = 150/7, which yield a 95% credible interval for pi1 of (0.4, 0.6). In the presence of prior information, these assumptions can be relaxed and the parameters for the prior chosen accordingly to reflect the background rates of misspecified relationships.

We assume Beta (Β) priors for both the genotyping error rate and allele frequency at locus l, such that

where ε reflects the expected genotyping error rate for all the SNPs in the particular platform and φ effectively controls the strength of our belief in this expected error rate. The parameters ξ1 and ξ2 can be chosen based on information of the allele frequency for each SNP a priori. In our analyses, we let ε = 0.01, with φ = 10. Also we assume no prior information on the allele frequencies and we let ξ1 = ξ2 = 1, which is the same as assuming an uninformative uniform distribution for the allele frequencies.

There is often a strong correlation between genotyping error rates and call rates, where SNPs with lower call rates tend to have more genotyping errors. This is a common artifact as researchers, in attempts to increase the call rates of SNPs with low call rates, may pass genotype calls which are of lower quality. Thus in evaluating the weight for each SNP, we consider both genotyping errors and missing genotypes as evidence of poorer performance for a SNP and the weight for SNP l is evaluated deterministically with the relationship

where # abbreviates for “the number of”, and the numerator is calculated for SNP l.

Given the observed genotypes, X, and conditional on knowing the trio relationship of the n pedigrees, Z, the posterior distribution for the allele frequency for SNP l is

with nlk denoting the number of copies of allele k observed for SNP l from suitable individuals. We define the set of suitable individuals to include the parents from true trios, all the individuals from misspecified parents trios, the putative mothers from misspecified-father trios and the putative fathers from misspecified-mother trios.

The corresponding posterior distribution for the genotyping error rate is

where is obtained from counting the number of trios with genotyping errors at SNP l.

The matrix of pedigree inconsistencies, M, does not change given the observed genotypes. However the entries in the binary matrix for genotyping errors, G, depend probabilistically on the trio relationship, the observed genotype combination for the trio xil, and the genotyping error rate for the corresponding SNP. While the program Nucl3ar allows for a flexible specification of the error model, in our analysis, we have made the simplifying assumption that at most one genotyping error can occur for each trio, and conditional on the occurrence of an error, it is twice as likely for a single allele error than an error involving both alleles. For example, if the two possible alleles at a SNP are C and T, it is twice as likely for a genotyping error of the form CC → CT as compared to CC → TT. The posterior distribution of gil follows a Bernoulli distribution with a success probability of

In assessing the conditional likelihoods Pr(xil|gil = 1, mil, zi) (and Pr(xil|gil = 0, mil), zi), we need to consider all possible combinations of trio genotypes which are consistent with the observed genotypes xil in the presence (or absence) of a genotyping error (see Supplementary Material L1).

Conditional on the observed genotypes, we can calculate the posterior distribution of Z as

Specifically, in the setting where all the loci are unlinked and when the occurrence of a genotyping error at any SNP for each trio is independent of the actual relationship between the members of the trio, we use a weighted likelihood approach to calculate the posterior probabilities. In particular, the log-likelihood of the observed genotypes for trio i, xi, is calculated as

The posterior probability that trio i is assigned to relationship j is the normalized probability

In order to average over the uncertainties of the posterior distributions, we construct a Markov chain using Gibbs sampling [33]. We can start the chain by sampling each variable from the respective prior distributions, and the algorithm iterates through the following steps:

Sample F(t) from Pr(F|X, G(t−1), E(t−1), M(t−1), P(t−1), Z(t−1)).

Sample G(t) from Pr(G|X, F(t), E(t−1), M(t−1), P(t−1), Z(t−1)).

Sample E(t) from Pr(E|X, F(t), G(t), M(t−1), P(t−1), Z(t−1)).

Sample M(t) from Pr(M|X, F(t), G(t), E(t), P(t−1), Z(t−1)).

Update W deterministically.

Sample P(t) from Pr(P|X, F(t), G(t), E(t), M(t), Z(t−1)).

Sample Z(t) from Pr(Z|X, F(t), G(t), E(t), M(t), P(t)).

By letting the chain run for sufficiently large number of iterations (the burn-in phase of a MCMC), we expect that the sampled values during every subsequent c iterations to be approximately independent random samples from the respective posterior distributions (c is the thinning interval). While inference on the assigned trio relationship can be performed on Z by effectively counting the number of times that a particular relationship is assigned to each trio, we choose instead to utilize the actual posterior probabilities obtained for each trio during the relevant samplings after burn-in. Thus, for every trio, we have the empirical distribution of the posterior probability that it has a particular trio relationship. The user can then choose the trios which are most likely to be true by specifying the desired precision on the mean posterior probability for each of the four relationships. We do not specify a recommended threshold but allow the user to tune the tradeoff between identifying more true trios and accuracy (see Application). In our applications, we have chosen a burn-in of 200 iterations, a thinning interval of 10 iterations, and the chain is run to obtain 1000 samplings.

3. APPLICATION

We tested the performance of our method using a series of simulations. Simulated genotype data were generated for four relationships: parent-offspring trios; three unrelated individuals; mother-child and an unrelated male; father-child and a maternal aunt. Trios with unrelated individuals or aunts were disguised as parent-offspring trios. Ten replicates of one thousand trios were generated for each trio type, and we simulated such datasets for 12, 24 and 48 SNPs. As paternal and maternal misspecification types are symmetrical in the absence of incorporating SNPs on the sex chromosomes, we would expect, for example, a mother-child and an unrelated male trio to mirror a father-child and unrelated female trio. We thus assessed the subtle relationship misspecification where a maternal aunt is disguised as the putative mother since the aunt on average shares half her alleles with the true mother and this misspecification type serves as a useful test of sensitivity.

The data was simulated using SimPed [34]. Markers were grouped with 6 SNPs on each chromosome with no linkage disequilibrium but spaced at a genetic distance equivalent to 10kb (assuming a smooth recombination rate of 1cM/Mb). SNP minor allele frequencies were chosen from a Uniform(0.05, 0.5) distribution. Separate missing genotype (M) and error rates (E) for each SNP were both drawn randomly from a Uniform(0, 0.05) distribution. A simple error model was employed whereby each diploid genotype had a probability M of being missing, and probability E of being replaced by a genotype drawn randomly from a distribution under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium based on the allele frequency of the marker.

Using Nucl3ar we assigned trios to be true parent-offspring triads if their corresponding posterior probability was above a specified threshold. In addition to the thresholds of 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 and 0.95, we also considered assigning each trio to the relationship which had the maximum posterior probability. We compared Nucl3ar against the available programs for assessing pedigree relationships: Relcheck [25,26], Prest [35], Relpair [28,36] and Eclipse3 [29]. In order to provide an objective comparison between the various methods, we have described how we operated and interpreted the output from these programs in the Supplementary Materials (L2).

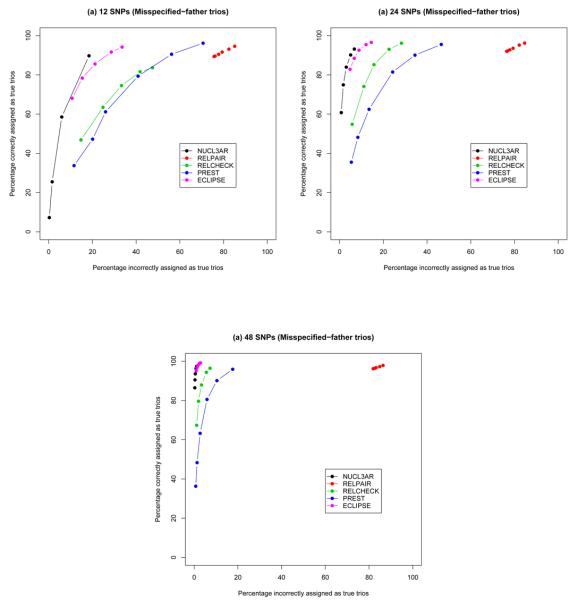

We evaluated the number of trios which has either been correctly and incorrectly assigned as true trios (Figure 3). The power of each application is evaluated as the proportion of true nuclear trios which have been assigned correctly. Type I error rates are assessed as the proportions of misspecified trios that have been incorrectly assigned as true.

Fig. 3.

Percentages of correct and incorrect trio assignment as true, for (a) 12 SNPs; (b) 24 SNPs; (c) 48 SNPs. The x-axes show the percentages of the data simulated with misspecified fathers which have been incorrectly assigned as true trios. The y-axes show the percentages of the data simulated as true trios which have been correctly assigned as true trios. The curves are obtained by considering the various thresholds: Nucl3ar (black - maximum posterior probability, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 0.95), Relpair (red - 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 0.95, 0.99, 0.999), Relcheck (green - 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0), Prest (blue - 0.4, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, 0.05, 0.02), Eclipse3 (pink - 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0).

Our results show that, for 12 and 24 SNPs, Nucl3ar outperformed the rest of the methods, in terms of achieving higher sensitivity and specificity for identifying misspecified father-mother-offspring trio relationships. Figure 3 shows the performance of the different methods for simulated misspecified-father trios, and similar plots for father-aunt-offspring trios and trios for 3 unrelated individuals can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). Nucl3ar and Eclipse3 performed similarly for 48 SNPs while performing better than Prest, Relcheck and Relpair. It should be noted that the mean error rates and exact allele frequencies used to generate the simulated data was directly submitted to Eclipse3, Prest, Relcheck and Relpair, while Nucl3ar was left to derive these values. For simulated data containing misspecified-father trios with 24 SNPs, Nucl3ar has the lowest rate of erroneous assignment as true trios (~5%) for a given specificity of ~90%, while Eclipse3 comes closest at 9% and the remaining methods achieve error rates > 10% (see Table 1). Among our misspecified families, the simulated data with 3 unrelated individuals and father-aunt-offspring have the lowest and highest rates of erroneous inference respectively, and this is true across all the methods (Table 1). Nucl3ar and Eclipse3 are most sensitive to the subtle misspecifications presented by father-aunt-offspring trios, erroneously assigning ~34% and ~41% as true trios respectively. The rest of the methods erroneously inferred more than half of the father-aunt-offspring trios as true trios (Table 1). Nucl3ar also has the lowest rates of incorrectly assigning false trios as true for the simulated 3 unrelated individuals and false father trios (Table 1).

Table 1.

Proportion of the simulated trios assigned as true father-mother-offspring trios averaged across 10 runs in each scenario. The four simulation scenarios are: simulated true father-mother-offspring trios; simulated 3 unrelated individuals (effectively misspecified parents); simulated misspecified-father trios; simulated father-aunt-offspring trios. Data for 24 SNPs are simulated for 1000 trios in each run. The adopted threshold for each method is represented in brackets after each method.

| Proportion assigned as true trios |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True trios | 3 unrelated ind. | False father trios | Father-aunt-offspring | |

| Nucl3ar (0.6) | 0.901 | 0.008 | 0.050 | 0.342 |

| Relpair (0.99) | 0.950 | 0.144 | 0.767 | 0.816 |

| Relcheck (0.5) | 0.852 | 0.060 | 0.226 | 0.547 |

| Prest (0.05) | 0.905 | 0.147 | 0.345 | 0.694 |

| Eclipse3 (0.5) | 0.884 | 0.011 | 0.089 | 0.409 |

For trios that have been assigned as false by Nucl3ar, the method makes a further judgement as to whether one or both parents have been misspecified. If it is the former, the method also infers which parent-offspring relationship has been misspecified. We assess the accuracy for identifying the misspecified relationship from the simulated data. With 48 SNPs and at a posterior probability threshold of 0.9, Nucl3ar correctly identified 95.6% of fathers among misspecified-father trios (see Table 2). For trios which consist of 3 unrelated individuals, both parents were identified as the source of misspecification in 79.1% of trios (and a further 20.8% of the trios were identified with single parent-offspring misspecifications). The lower rate for trios with 3 unrelated individuals was a result of preferentially assigning false trios to a single misspecified parent-offspring relationship rather than a complete misspecification of the trio relationship (misspecified parents). This rate changes to 98.9% if we specify that it is equally likely to have both parents misspecified compared to a single parent misspecification. Simulated father-aunt-offspring trios are subtle forms of maternal misspecification, and Nucl3ar was able to correctly identify two-thirds of these (Table 2). In addition to inferring misspecified parent-offspring relationships, Nucl3ar also estimates allele frequencies, as well as rates of missingness and genotyping errors for each SNP. Estimated rates show extremely high correlation to the simulated rates, with Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.998 and 0.957 for the allele frequencies, and the combined rate of missingness and genotyping error respectively (Supplementary Figures S4a and S4b).

Table 2.

Proportion of simulated data assigned to the four possible categories (true trios, misspecified parents, misspecified-father and misspecified-mother), based on simulations performed with 48 SNPs and a threshold of 0.9 for Nucl3ar.

| Assigned Relationship |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated Relationship | True | Misspecified parents | Misspecified-father | Misspecified-mother |

| True trios | 0.897 | 0.000 | 0.051 | 0.052 |

| 3 unrelated ind. | 0.001 | 0.791 | 0.118 | 0.090 |

| False father trios | 0.009 | 0.026 | 0.956 | 0.008 |

| Father-aunt-offspring | 0.265 | 0.011 | 0.063 | 0.661 |

We applied Nucl3ar and Eclipse3 to a real set of genotyping data from 659 putative parent-offspring trios collected as part of an ongoing genome-wide study of the genetic factors associated with malaria susceptibility (www.malariagen.net). The dataset comprised results for 48 SNPs and intentionally included some assays with poor genotyping performance (Figure 4).

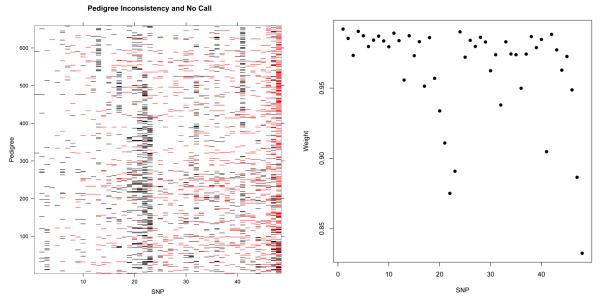

Fig. 4.

Left: Representation of pedigree inconsistent genotype configurations (red) and genotyping failures (black) for 659 trios across 48 SNPs. The low number of pedigree inconsistent genotype configurations for the first seven SNPs are due to the low allele frequencies (< 5%). A trio is considered to experience a genotyping failure at a SNP if at least one of three individuals has a missing genotype at this SNP. We have ordered the markers by increasing number of mendelian errors. Right: Plot of the Nucl3ar inferred weighting for each of the 48 SNPs used in the analysis. The SNPs which have significantly lower weightings corresponded correctly to SNPs with greater extent of pedigree inconsistent genotype configurations.

Using a threshold of 0.9, Nucl3ar identified 503 trios as true parent-offspring trios, 85 with misspecified fathers, 11 with misspecified mothers, 16 with two misspecified parents. 44 putative trios did not meet the threshold and thus were unassigned. The distribution of SNP weighting from Nucl3ar appropriately down-weighted markers with high rates of mendelian error or missing genotypes (Figure 4). Unlike the simulations where a known mean error rate was given to Eclipse3, here we used a range of estimated error rates. Assuming a constant error rate across markers (particularly in the presence of a number of poor assays) appears to make Eclipse3 particularly conservative, and we found the output to be relatively sensitive to the error rate used (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of true trios identified by Eclipse3 out of 659 putative parent-offspring trios collected as part of an ongoing genome-wide study in malaria. We assumed different error rates when running Eclipse3 and count the number of trios identified by Eclipse3 as true.

| Error rate (%) | Number of true trios |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | 366 |

| 1.0 | 386 |

| 2.5 | 400 |

| 5.0 | 409 |

| 10.0 | 411 |

4. DISCUSSION

We have introduced a method for detecting misspecified relationships in the setting of nuclear family trios with limited SNP genotyping data. The approach evaluates the evidence from all three individuals jointly and infers probabilistically whether the relationship is misspecified. Set within a Bayesian framework, the method calculates the posterior probabilities of four possible scenarios: no misspecification, maternal misspecification, paternal misspecification, or misspecification of both parents. We believe the use of posterior probabilities are intuitively easier to interpret, compared to the conventional use of likelihood ratios and derived significances. The accuracy of such statistical significances often relies on asymptotics, and the interpretation of the results can be complicated by issues of multiple testings. With posterior probabilities, pedigrees can also be ranked according to the probability of being true. This can be helpful for prioritizing trios, for example, in selecting a subset of samples from a larger collection for further expensive genotyping.

To our knowledge, this is the only method that estimates and incorporates varying rates of genotyping errors for different SNPs while performing the pedigree assessment. In existing methods, all markers share a common genotyping error rate (although depending on the complexity of the error model, this can be composed of two or more probabilities), this ignores potentially large differences in marker performance. Furthermore these error rates, which can be difficult to estimate, must be specified by the user. Our analysis of empirical trio data suggests that results obtained from other approaches are sensitive to successful estimation of the error rates. Our method uses the rate of missingness and genotyping error for each SNP to weigh the contribution of each SNP accordingly in the analysis. We believe this reflects the decision-making process that a rational user will take, which is to discount the evidence provided by SNPs with higher degrees of missingness and higher rates of genotyping error.

We emphasize that the inference of the underlying relationship for misspecified trios is not the focus of our application in its present form, and alternative methods (such as Eclipse3) remain more informative for this task. Detection of relationship misspecification relies on having adequate marker information; marker number, missingness, error rates, allele number and frequency (see Supplementary Material, Figure S5) all affect the information available. Although we have proposed a method for handling limited SNP data, the optimal approach remains maximizing the quality and quantity of polymorphic marker data. While the methodology can also be extended to utilise multi-allelic markers (e.g. microsatellites) that are more informative than SNPs, it will be comparably more challenging to model the errors for such highly polymorphic markers. Given the ease and relatively low costs of genotyping SNPs, it is increasingly common for laboratories to genotype a number of SNPs for each sample to produce a genetic barcode. Our method provides a convenient tool which utilises these potentially limited SNP data to investigate the authenticity of the family relationships.

Our method assumes that the SNPs are in sufficiently weak LD so that the joint likelihood of the SNPs can be approximated by the product of the marginal likelihoods from each SNP. It is less clear how the information provided by the panel of SNPs will change when the panel contains SNPs that are in strong LD. SNPs in strong LD provide redundant information about each other. This could be employed to detect genotyping errors: for example, if two markers were known to be in high LD and only one exhibited a mendelian error for a trio, this increases the likelihood that the mendelian error is caused by a genotyping error; conversely if both demonstrated mendelian inconsistencies, this would provide consistent evidence for pedigree misspecification. Although we are currently extending the present framework to handle correlation between SNPs, the current version of Nucl3ar appears to perform reasonably well in the presence of moderate LD between SNPs (results not shown).

One advantage conferred by the use of pedigree data in an association study is the robustness against effects of population structure, as each pedigree is effectively evaluated independently and the results pooled across the pedigrees. Our method of pedigree assessment however infers the allele frequency for each SNP using data from all the pedigrees, and the inferred allele frequencies may not be robust to the effects of population structure. As the method essentially assesses the presence of genotype configurations which are inconsistent with mendelian transmission, we believe that minor differences in allele frequencies will not substantially affect the performance. We tested our assumption by running the method on a dataset simulated with 48 SNPs according to the same specifications as described in Applications, except for modifications in the allele frequencies to reflect the presence of population structure as represented by: the first dataset containing 1000 true trios simulated such that the first 200 trios have allele frequencies derived from the HapMap Japanese population [37] and the remaining 800 have allele frequencies derived from the HapMap Chinese population; the second dataset containing 1000 true trios simulated such that the first 200 trios have frequencies derived from the HapMap CEPH population and the remaining 800 have frequencies derived from the HapMap Yoruba population from Ibadan in Nigeria. The first dataset represents the presence of fine-scale population structure and has a SNP-averaged Fst of 0.007, while the second has a SNP-averaged Fst of 0.088. We see that there is no significant degradation in the performance of Nucl3ar as a result of either fine- or broad-scale population structure (Table 4).

Table 4.

Proportion of simulated data assigned to each of the four possible trio relationships, at a threshold of 0.9 for Nucl3ar. In the first scenario, 1000 trios were analyzed of which 200 and 800 trios are simulated from two populations with levels of population differentiation similar to the HapMap Japanese and Chinese respectively, which we have loosely defined to reflect fine-scale population differentiation; in the second scenario, 1000 trios were analyzed of which 200 and 800 trios are simulated from two populations with levels of population differentiation similar to the HapMap CEPHs and Yorubas respectively, which we have loosely defined to reflect broad-scale population differentiation. There are no detectable differences in the performance of Nucl3ar in both scenarios.

| Assigned Relationship |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | Misspecified parents | Misspecified-father | Misspecified-mother | |

| Fine-scale | ||||

| Pop. 1 (200 trios) | 0.972 | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.007 |

| Pop. 2 (800 trios) | 0.963 | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.014 |

| Broad-scale | ||||

| Pop. 1 (200 trios) | 0.987 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 |

| Pop. 2 (800 trios) | 0.992 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

In summary, association studies using nuclear family trios with an affected offspring need to appraise the genuineness of the pedigrees. We have described a method optimized to infer the authenticity of trios in scenarios when the amount of available genetic data are relatively limited. There are practical situations where efficient detection of misspecified trios can save valuable resources and prevent unnecessary distortion of association statistics. Our approach utilizes trio information, down-weighs SNPs with poor performance and does not require the user to know the rates of genotyping error. Through studies of simulated and empirical data we have shown our approach handles large trio datasets with limited SNP data better than many existing methods for assessing relationship misspecification.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge funding from the Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative (Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust and FNIH) and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council. A.F. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Training Fellowship.

Footnotes

This manuscript was prepared with the AAS  macros v5.2.

macros v5.2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalli-Sforza LL, Menozzi P, Piazza A. The history and geography of human genes. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reich DE, Goldstein DB. Detecting association in a case-control study while correcting for population stratification. Genet Epidemiol. 2001;20:4–16. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(200101)20:1<4::AID-GEPI2>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman ML, Reich D, Penney KL, McDonald GJ, Mignault AA, Patterson N, Gabriel SB, Topol EJ, Smoller JW, Pato CN, Pato MT, Petryshen TL, Kolonel LN, Lander ES, Sklar P, Henderson B, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D. Assessing the impact of population stratification on genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2004;36:388–393. doi: 10.1038/ng1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchini J, Cardon LR, Phillips MS, Donnelly P. The effects of human population structure on large genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2004;36:512–517. doi: 10.1038/ng1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helgason A, Yngvadóttir B, Hrafnkelsson B, Gulcher J, Stefánsson K. An Icelandic example of the impact of population structure on association studies. Nat Genet. 2005;37:90–95. doi: 10.1038/ng1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laird NM, Lange C. Family-based designs in the age of large-scale gene-association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:385–394. doi: 10.1038/nrg1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falk CT, Rubinstein P. Haplotype relative risks: an easy reliable way to construct a proper control sample for risk calculations. Ann Hum Genet. 1987;51:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1987.tb00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson G. Mapping disease genes: family-based association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:487–498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terwilliger JD, Ott J. A haplotype-based ‘haplotype relative risk’ approach to detecting allelic associations. Hum Hered. 1992;42:337–346. doi: 10.1159/000154096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spielman RS, McGinnis RE, Ewens WJ. Transmission test for linkage disequilibrium: the insulin gene region and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:506–516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinberg CR, Wilcox AJ, Lie RT. A log-linear approach to case-parent-triad data: assessing effects of disease genes that act either directly or through maternal effects and that may be subject to parental imprinting. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:969–978. doi: 10.1086/301802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laird NM, Horvath S, Xu X. Implementing a unified approach to family-based tests of association. Genet Epidemiol. 2000;19:S36–42. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(2000)19:1+<::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordell HJ, Clayton DG. A unified stepwise regression procedure for evaluating the relative effects of polymorphisms within a gene using case/control or family data: application to HLA in type 1 diabetes. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:124–141. doi: 10.1086/338007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewens WJ, Spielman RS. The transmission/disequilibrium test: history, subdivision, and admixture. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:455–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Hughes S, Ashton JR. Measuring paternal discrepancy and its public health consequences. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:749–754. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.036517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerda-Flores RM, Barton SA, Marty-Gonzalex LF, Rivas F, Chakraborty R. Estimation of nonpaternity in the Mexican population of Nuevo Leon: a validation study with blood group markers. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1999;109:281–293. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199907)109:3<281::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon D, Matise TC, Heath SC, Ott J. Power loss for multiallelic transmission/disequilibrium test when errors introduced: GAW11 simulated data. Genet Epidemiol. 1999;17:S587–592. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370170795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heath SC. A bias in TDT due to undetected genotyping errors. Am J Hum Genet Suppl. 1998;63:A292. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell AA, Cutler DJ, Chakravarti A. Undetected genotyping errors cause apparent overtransmission of common alleles in the transmission/disequilibrium test. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:598–610. doi: 10.1086/368203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon D, Heath SC, Liu X, Ott J. A transmission/disequilibrium test that allows for genotyping errors in the analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphism data. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:371–380. doi: 10.1086/321981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon D, Haynes C, Johnnidis C, Patel SB, Bowcock AM, Ott J. A transmission disequilibrium test for general pedigrees that is robust to the presence of random genotyping errors and any number of untyped parents. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:752–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon D, Heath SC, Ott J. True pedigree errors more frequent than apparent errors for single nucleotide polymorphisms. Hum Hered. 1999;49:65–70. doi: 10.1159/000022846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blouin MS, Parsons M, Lacaille V, Lotz S. Use of microsatellite loci to classify individuals by relatedness. Mol Ecol. 1996;5:393–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1996.tb00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boehnke M, Cox NJ. Accurate inference of relationships in sib-pair linkage studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:423–429. doi: 10.1086/514862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broman KW, Weber JL. Estimation of pairwise relationships in the presence of genotyping errors. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1563–1564. doi: 10.1086/302112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch M, Ritland K. Estimation of pairwise relatedness with molecular markers. Genetics. 1999;152:1753–1766. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein MP, Duren WL, Boehnke M. Improved inference of relationship for pairs of individuals. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1219–1231. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9297(07)62952-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieberts SK, Wijsman EM, Thompson EA. Relationship inference from trios of individuals, in the presence of typing error. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:170–180. doi: 10.1086/338444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J. An estimator of pairwise relatedness using molecular markers. Genetics. 2002;160:1203–1215. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.3.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blouin MS. DNA-based methods for pedigree reconstruction and kinship analysis in natural populations. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18:503–511. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones AG, Ardren WR. Methods of parentage analysis in natural populations. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:2511–2523. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilks WR, Richardson S, Spiegelhalter DJ, editors. Markov chain Monte Carlo in practice. Chapman & Hall; London: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leal SM, Yan K, Müller-Myhsok B. SimPed: A simulation program to generate haplotype and genotype data for pedigree structures. Hum Hered. 2005;60:119–122. doi: 10.1159/000088914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McPeek M, Sun L. Statistical tests for detection of misspecified relationships by use of genome-screen data. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1076–1094. doi: 10.1086/302800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duren WL, Epstein M, Li M, Boehnke M. RELPAIR: A Program that Infers the Relationships of Pairs of Individuals Based on Marker Data. Version 2.0.1, http://csg.sph.umich.edu/boehnke/relpair.php, 2004.

- 37.International HapMap Consortium A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.