Abstract

Background and purpose:

The biogenic amine, histamine plays a pathophysiological regulatory role in cellular processes of a variety of immune cells. This work analyses the actions of histamine on γδ-T lymphocytes, isolated from human peripheral blood, which are critically involved in immunological surveillance of tumours.

Experimental approach:

We have analysed effects of histamine on the intracellular calcium, actin reorganization, migratory response and the interaction of human γδ T cells with tumour cells such as the A2058 human melanoma cell line, the human Burkitt's Non-Hodgkin lymphoma cell line Raji, the T-lymphoblastic lymphoma cell line Jurkat and the natural killer cell-sensitive erythroleukaemia cell line, K562.

Key results:

γδ T lymphocytes express mRNA for different histamine receptor subtypes. In human peripheral blood γδ T cells, histamine stimulated Pertussis toxin-sensitive intracellular calcium increase, actin polymerization and chemotaxis. However, histamine inhibited the spontaneous cytolytic activity of γδ T cells towards several tumour cell lines in a cholera toxin-sensitive manner. A histamine H4 receptor antagonist abolished the histamine induced γδ T cell migratory response. A histamine H2 receptor agonist inhibited γδ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Conclusions and implications:

Histamine activated signalling pathways typical of chemotaxis (Gi protein-dependent actin reorganization, increase of intracellular calcium) and induced migratory responses in γδ T lymphocytes, via the H4 receptor, whereas it down-regulated γδ T cell mediated cytotoxicity through H2 receptors and Gs protein-coupled signalling. Our data suggest that histamine activated γδ T cells could modulate immunological surveillance of tumour tissue.

Keywords: histamine, γδ T lymphocytes, migration, cytotoxicity, G protein

Introduction

γδ T cells are a population of lymphocytes expressing functional γδ T cell receptor (TCR) genes (Brenner et al., 1986). This subtype of T cells, presumably an ancient type of lymphocytes, is derived from haematopoietic stem cells that share certain characteristics with other immune cells, such as antigen presentation, immune modulatory properties and cytolytic activity (Nakata et al., 1990; Girardi, 2006). Two main subsets of γδ T cells are distinguished according to their location. Resident γδ T cells are found in skin, uterine and epithelial tissues, whereas circulating/systemic γδ T cells can be isolated from peripheral blood or lymphoid tissues (Kabelitz, 1993; Chen, 2002).

In contrast to αβ T lymphocytes, γδ T cells do not need antigens presented on classical MHC-molecules for recognition (Kabelitz et al., 2000). Instead, they recognize antigens bound to CD1 molecules. They are able to recognize a number of natural phosphoantigens derived from plants, bacteria, protozoa and viruses, as well as endogenous ligands derived from tumours (Bukowski et al., 1995; Bauer et al., 1999; Boullier et al., 1999; Selin et al., 2001). Several lines of evidence involve γδ T cells in primary host defence as well as in tumour surveillance; they are also known to attack bacterial and virus-bearing cells as well as transformed cells (Wrobel et al., 2007). This cytotoxic activity is mediated by production and release of perforin and granzymes (Nakata et al., 1990; Girardi, 2006). The antitumour activity of γδ T cells either is mediated via endogenous ligands in γδ TCR-dependent fashion or depends on the interaction of the cells with the natural killer (NK) cell receptor, NKG2D (Bukowski et al., 1995; Wrobel et al., 2007).

Histamine (β-imidazolylethylamine) is a biogenic amine, stored in the granules of tissue mast cells, blood basophils and neural cells (Riley and West, 1952; Kinet, 1999). It is involved in different physiological and pathological responses, such as the immune response, gastric acid secretion, neurotransmission and angiogenesis (Brimble and Wallis, 1973; Akdis and Simons, 2006; Hegyesi et al., 2008; Yakabi et al., 2008; Zampeli and Tiligada, 2009). The expression of the enzyme that forms histamine, histidine decarboxylase, in several leukaemia and highly malignant forms of cancer, such as melanoma, small cell lung carcinoma and breast adenocarcinoma tumour, suggests that histamine plays a functional role in the pathogenesis of various types of cancer (Matsuki et al., 2003; Sonobe et al., 2004; Aichberger et al., 2006; Hegyesi et al., 2008).

Histamine is known to regulate humoral and cellular immunity by controlling the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, the expression of adhesion molecules and the migration of inflammatory cells such as eosinophils, dendritic cells, NK cells and αβ T cells (Gutzmer et al., 2005; Damaj et al., 2007). The pleiotropic effects of histamine are mediated by four types of receptors (histamine H1, H2, H3 and H4; nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2008). They belong to the serpentine (7-TM) receptor superfamily and couple to different types of G proteins; these proteins initiate distinct intracellular signalling pathways (Hill et al., 1997). Histamine H1 receptors preferentially couple to Gq/11 proteins to mediate the mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ as well as the activation of protein kinase C, extracellular signal regulated kinase and the transcription factor, nuclear factor κB (Matsubara et al., 2005). The H2 receptor interacts with Gs proteins and stimulates cAMP accumulation (Baker, 2008). H3 receptors are primarily expressed in the brain, inhibit cAMP formation and regulate intracellular Ca2+ transients (Drutel et al., 2001). The H4 receptor regulates intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and chemotaxis in mast cells, eosinophils and NK cells via Pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi proteins (Damaj et al., 2007; Leurs et al., 2009).

In the current work we examine the biological activity of histamine in γδ T cells. We provide evidence for functional expression of histamine H2 and H4 receptors and show that histamine induces intracellular Ca2+ transients, actin polymerization and chemotaxis via H4 receptors, whereas H2 receptors promote cAMP accumulation and down-regulate the cytotoxicity of γδ T cells towards different tumour cell lines.

Methods

Preparation of γδ T cells

The use of human cells was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Jena. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated using the Ficoll separation protocol (Haas et al., 1993). Briefly, a density gradient centrifugation of buffy coats was performed. The leukocyte-containing pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.2, supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 2 mM EDTA, and the cells were labelled with an anti-TCR γδ hapten-antibody and anti-hapten micro-beads-fluoro-isothiocyanate (FITC) antibody. Labelled cells were separated with magnetic separation columns. Positive selected γδ T cells were cultured for 7–10 days in the presence of Phaseolus vulgaris phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (2 µg·mL−1) for 3 days and interleukin (IL)-2 (100 IU·mL−1) until day 7 (Nakata et al., 1990; Argentati et al., 2003; Wrobel et al., 2007).

mRNA isolation, reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

mRNA was isolated from 1 × 106 human peripheral blood γδ T cells using High Pure RNA isolation Kit. Fast Start Taq cDNA Polymerase Kit and Fast Start Taq DNA Polymerase Kit were used to obtain cDNA and PCR products. The primers were designed to recognize sequences specific for each target cDNA:

H1R (403 bp): sense 5′-CATTCTGGGGGCCTGGTTTCTCT-3′ antisense 5′-CTTGGGGGTTTGGGATGGTGACT-3′

H2R (497 bp): sense 5′-CCCGGCTCCGCAACCTGA-3′ antisense 5′-CTGATCCCGGGCGACCTTGA-3′

H3R (589 bp): sense 5′-CAGCTACGACCGCTTCTTGTC-3′ antisense 5′-GGACCCTTCTTTGAGTGAGC-3′

H4R (396 bp): sense 5′-GGTACATCCTTGCCATCACATCAT-3′ antisense 5′-ACTTGGCTAATCTCCTGGCTCTAA-3′

β2-micriglobuline (259 bp): 5′-CCTTGAGGCTATCCAGCGTA-3′ antisense 5′-GTTCACACGGCAGGCATACT-3′

Mobilization of intracellular Ca2+

Intracellular free Ca2+ was measured in Fura-2-labelled γδ T cells using the digital fluorescence microscope unit Attofluor (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) (Panther et al., 2001).

Filamentous (f) actin measurements

Samples of stimulated γδ T cells (106 per mL; 50 µL per sample) were fixed in a 7.4% formaldehyde buffer and mixed with the staining mixture containing 7.4% formaldehyde, 0.33 µM NBD-phallacidin and 1 mg·mL−1 lysophosphatidylcholine. The fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. The relative f-actin content was compared with unstimulated controls (Lagadari et al., 2009).

Migration assay

The chemotaxis of human peripheral blood γδ T cells was performed in 48-well-Microtechnic chambers from Neuro Probe (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Wells in the bottom of the chamber were filled with 29 µL medium containing the indicated concentration of stimulus. Over this filled chamber, a polycarbonate membrane (thickness 10 µm, diameter of the pores 8 µm) and a gasket made of silicone were fixed. The device was screwed on the top of the gasket and the cells were added in 29 µL per well (resuspended in a concentration of 1 × 105 per mL) in the upper wells of the chamber. For the assay, the chamber was incubated for 240 min at 37°C. The non-migrating cells from the wells of the upper chamber were removed after the incubation period; the filter and gasket were then removed and the cells from the bottom chamber were collected, fixed in formaldehyde (3.7%) and counted by flow cytometry. A chemotactic index (CI) was calculated as the ratio between stimulated and random migration.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was determined with a standard 51Cr release assay. Target cells were labelled at 37°C for 1 h with 100 µCi Na251CrO4. Cells were washed and resuspended at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells·mL−1 in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum. Effector and target cells at different ratios (10:1, 5:1 and 2.5:1) were placed into individual wells of 96-well plates in a total volume of 200 µL at 37°C for 4 h. After incubation, 100 µL culture supernatant was collected from each well, mixed with MicroScint-40 cocktail and analysed with a gamma counter (Topcount™, Packard Instruments). To obtain the value of total lysis, target cells were incubated with 2% Triton-X. Percentage of specific lysis was calculated using the following formula:

|

Measurement of cAMP levels

γδ T cells (1 × 106 per mL) were fixed and permeabilized before intracellular staining was performed. The amount of intracellular cAMP in the γδ T cell preparation was determined by flow cytometry (Pepe et al., 1994).

Cell lines

The A2058 human melanoma cell line, the human Burkitt's non-Hodgkin lymphoma cell line Raji, the T-lymphoblastic lymphoma cell line Jurkat, and the erythroleukaemia cell line K562 originating from patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia and blast crisis were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 U·mL−1 penicillin, 10 U·mL−1 streptomycin and 1 mM L-glutamine (Herberman, 1981).

Western blot analysis

Immunoblotting was performed by running the samples on SDS–PAGE gels (20 µg protein per lane) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with the first antibody (1:2000) overnight at 4°C. After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10 000) for 1 h at room temperature. Proteins were detected by ECL (Amersham).

Statistical analysis

Significant differences between means (P < 0.05) were determined using the non-parametric two-tailed Student's t-test.

Materials

RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 U·mL−1 penicillin, 10 U·mL−1 streptomycin, 1 mM L-glutamine and Hanks BSS was purchased from Promocell (Heidelberg, Germany); recombinant human IL-2 (Proleukine) was from Chiron (Ratingen, Germany); histamine, thioperamide malate salt (T123), Phaseolus vulgaris PHA, cholera toxin, Pertussis toxin, lysophosphatidylcholine, Triton-X, ionomycin,the H1 receptor antagonist triprolidine, H2 receptor antagonist cimetidine and H3 receptor antagonist/H4 receptor agonist clobenpropit were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany); the H2 receptor agonist dimaprit from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany); the H3 receptor agonist imetit and the H1 receptor agonist 6-[2-(4-imidazolyl)ethylamino]-N-4-trifluoromethylphenyl)heptanecarboxamide dimaleate (HTMT dimaleate) from Biozol (Eiching, Germany); anti-TCR γδ hapten-antibody and anti-hapten MicroBeads-FITC antibody from Miltenyi Biotech GmbH (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany); Vg9 TCR antibody from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (Heidelberg, Germany); specific antibodies to histamine H1, H2, H3 or H4 receptors from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Heidelberg, Germany) High Pure RNA Kit, FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase Kit from Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany); SeaKem LE agarose from Cambrex (Taufkirchen, Germany); NBD-phallacidin and the histamine H1–H4 receptor primers from Invitrogen GmbH (Technologiepark Karlsruhe, Germany); FURA/2AM from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany); Nucleopore Track-Etch membrane filtration products from Whatman International Ltd. (Kent, UK); Na251CrO4 from Amersham (Freiburg, Germany); Microscint-40 from PerkinElmer (Jügesheim, Germany); cAMP antibody from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); and goat anti-mouse FITC-conjugated antibody from AL-Immunotools (Friesoythe, Germany).

Results

γδ T cells expressed histamine H1, H2 and H4 receptors

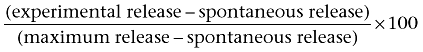

Using RT-PCR analysis, the expected products for the histamine H1, H2 and H4 receptor subtypes were detected in γδ T cells, isolated from human peripheral blood. In contrast, the H3 receptor was undetectable (Figure 1A). Omitting reverse transcriptase, no amplification products were observed in γδ T cells (data not shown). Expression of the H1, H2 and H4 receptor subtypes were detected at the protein level by Western blot analysis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Expression of mRNA of histamine H1, H2 and H4 receptors in human peripheral blood γδ T lymphocytes. (A) γδ T cells were isolated from human peripheral blood and expression of mRNA for histamine receptors was analysed. Lane 1 DNA molecular weight marker XIV (100–1500 bp); lane 2 H1 (403 bp); lane 3 H2 (497 bp); lane 4 H3 (589 bp); lane 5 H4 receptors (396 bp); lane 6 β2-microglobulin (259 bp). (B) γδ T cells were isolated from human peripheral blood and expression of different histamine receptor subtypes were analysed by Western blot analysis. Lane 1 H1 receptors (56 kDa); lane 2 H2 receptors (59 kDa); lane 3 H3 receptors (70 kDa); lane 4 H4 receptors (78/90 kDa), actin (43 kDa). Experiments were repeated three times with identical results.

Histamine induces actin polymerization, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and chemotaxis in γδ T cells through Pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi proteins

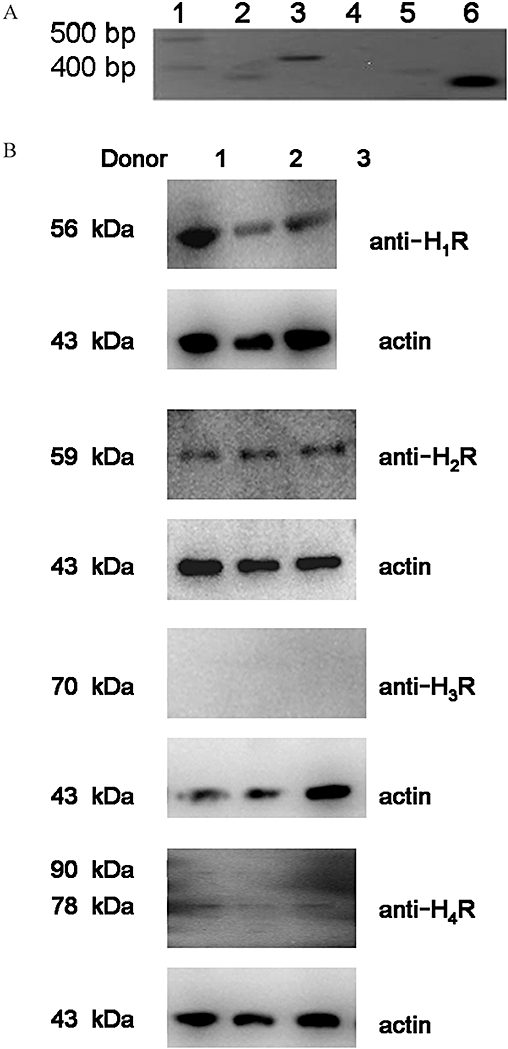

Histamine induces Ca2+ transients in different types of leukocytes (Feske, 2007) and in our experiments, histamine induced a rapid and concentration-dependent intracellular response in human γδ T cells (Figure 2A). Ca2+ transients are mainly caused by mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores or by their influx across the plasma membrane from the medium. In order to determine which of these two mechanisms was involved, experiments in the presence of EGTA in the medium were performed. Pre-incubation of γδ T cells with EGTA (4 mM) did not influence the histamine-initiated Ca2+ intracellular rise, implying the mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (data not shown). To investigate the involvement of Gi proteins in this response, we took advantage of Pertussis toxin. This toxin uncouples Gi proteins from serpentine receptors by ADP-ribosylation. Pretreating γδ T cells for 1 h with Pertussis toxin (100 ng·mL−1) strongly inhibited the histamine-induced Ca2+ increase in these cells which in turn implied the involvement of Gi proteins (Figure 2B). To check the responsiveness of Pertussis toxin-treated cells, experiments with ionomycin were performed. Ca2+ transients induced by ionomycin were not influenced by pretreatment of cells with Pertussis toxin (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Histamine induces calcium transients in human γδ T lymphocytes. (A) Cells were loaded with Fura-2/AM and stimulated with 0.01 µM, 0.1 µM and 1 µM histamine. Intracellular Ca2+ transients were followed by digital fluorescence microscopy and ratio between 340 nm and 380 nm was calculated. Representative data from one experiment are shown. Experiments were repeated three times with identical results. (B) Cells were pre-incubated with or without Pertussis toxin (100 ng·mL−1) for 90 min at 37°C and stimulated with 1 µM histamine. Calculated ratio after stimulation with and without histamine is shown. Data are means of three different experiments of three different donors ± SEM.

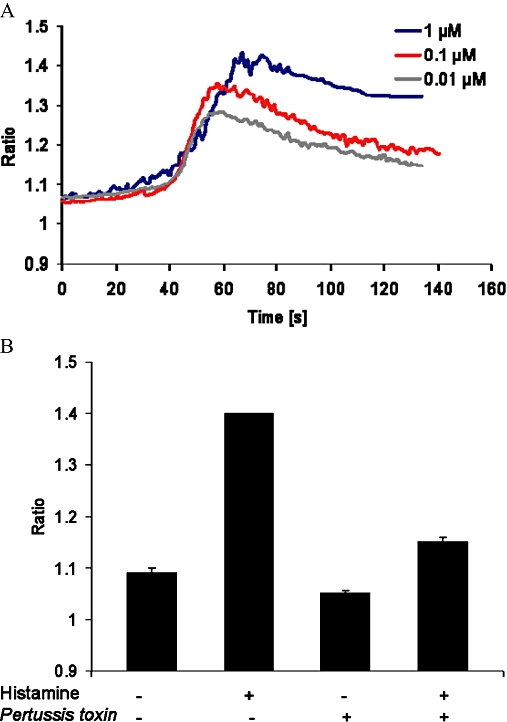

Next, actin reorganization was analysed by flow cytometry. A rapid increase in f-actin content (by about 60%) was induced when γδ T cells were stimulated with histamine (Figure 3A). The response was transient and reversible with maximal values within 30 s. To test the participation of Gi proteins in this response, γδ T cells were also pre-incubated with Pertussis toxin before being exposed to histamine (Figure 3B). Pretreating γδ T cells with Pertussis toxin almost completely abolished the effect of histamine on actin polymerization. In contrast, cells pretreated with cholera toxin did not differ significantly from control cells (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Effects of histamine on actin polymerization in human γδ T cells. (A) Cells were exposed to 0.1 µM–1 µM histamine and f-actin content was measured by flow cytometry. (B) Cells were pre-incubated with or without Pertussis toxin (100 ng·mL−1) for 90 min at 37°C and stimulated with 1 µM histamine for 30 s and the increase in f-actin content was analysed. (C) Cells were pre-incubated with or without cholera toxin (0.5 µg·mL−1) for 90 min at 37°C and stimulated with 1 µM histamine for 30 s and the f-actin content was analysed. (Line 1: unstimulated γδ T cells; Line 2: histamine stimulated γδ T cell; Line 3: cholera toxin pretreated γδ T cells; cholera toxin pretreated γδ T cells exposed to histamine) All data are means of three different experiments using three different donors ± SEM (***P < 0.0001; **P > 0.005; *P > 0.05). ns, not significant.

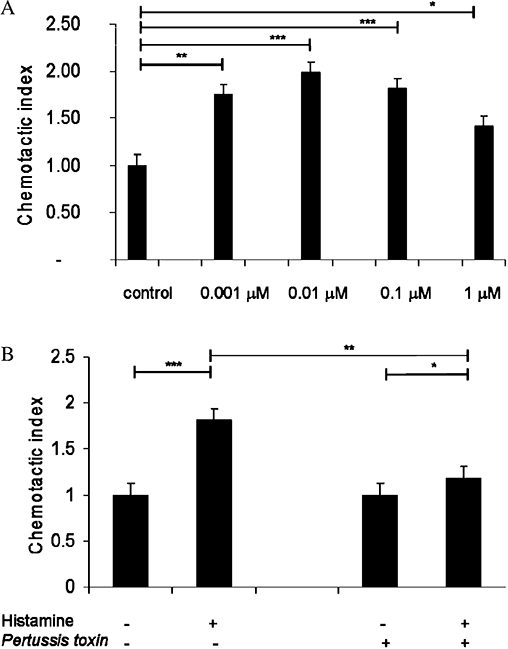

Intracellular Ca2+ transients and actin reorganization are prerequisites for cell migration. Therefore, human peripheral blood γδ T cells were exposed to different concentrations of histamine (0.01 µM–1 µM), and migration in the Boyden chambers was evaluated. Histamine induced the typical bell-shaped concentration dependent chemotactic response of γδ T lymphocytes (Figure 4A). Maximal chemotactic responses were observed upon stimulation with 0.01 µM histamine. Moreover, histamine-stimulated migration was also abolished by pretreating γδ T cells with Pertussis toxin (100 ng·mL−1) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of histamine on chemotaxis in human γδ T cells. Cells were exposed to different histamine concentrations (0.001 µM–1 µM) in Boyden chambers. Migrated cells in the bottom wells of the Boyden chamber were fixed with formalin and counted by flow cytometry. (B) γδ T cells were pretreated with Pertussis toxin for 1 h at 37°C and migration in response to 0.1 µM histamine was analysed. All data are means ± SEM (***P < 0.0001; **P > 0.005; *P > 0.05).

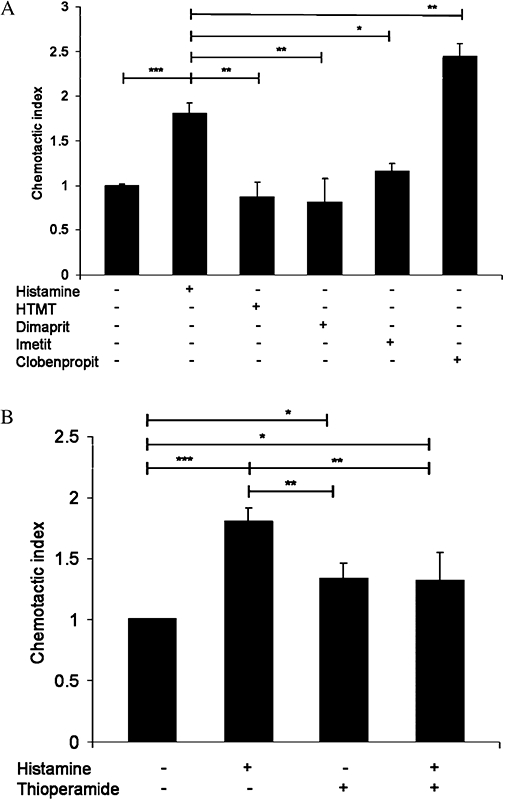

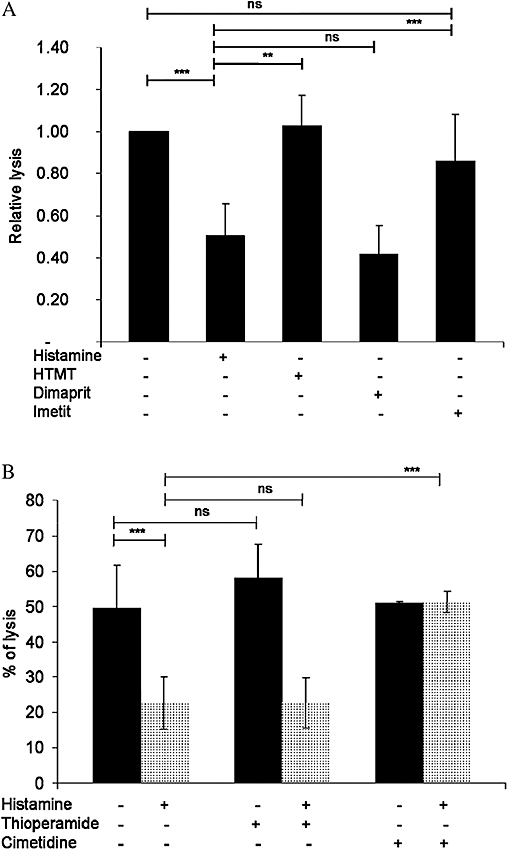

To determine the subtype of histamine receptor involved in the histamine-induced chemotactic response in human γδ T cells, we used receptor-selective agonists and antagonists. The histamine H1 receptor agonist HTMT, the H2 receptor agonist dimaprit and the H3 receptor agonist imetit did not induce any significant change in chemotactic activity (Figure 5A), whereas γδ T cells exposed to the H4 receptor agonist clobenpropit showed migration comparable to that after histamine in these cells. Pretreating γδ T cells with the H4 receptor antagonist thioperamide prevented histamine-induced migration (Figure 5B), suggesting that in γδ T cells, migration in response to histamine occurs specifically through the H4 receptors.

Figure 5.

Effects of histamine receptor agonists and antagonist on chemotaxis in γδ T cells. (A) γδ T cells isolated from healthy donors were exposed to histamine and selective agonists – HTMT for H1 receptors), dimaprit for H2 receptors, imetit for H3 receptors and clobenpropit for H4 receptors and migration was measured. (B) γδ T cells were pretreated with the H4 receptor antagonist thioperamide and the migration assay was performed. All data are means ± SEM (n= 3) (***P < 0.0001; **P > 0.005; *P > 0.05).

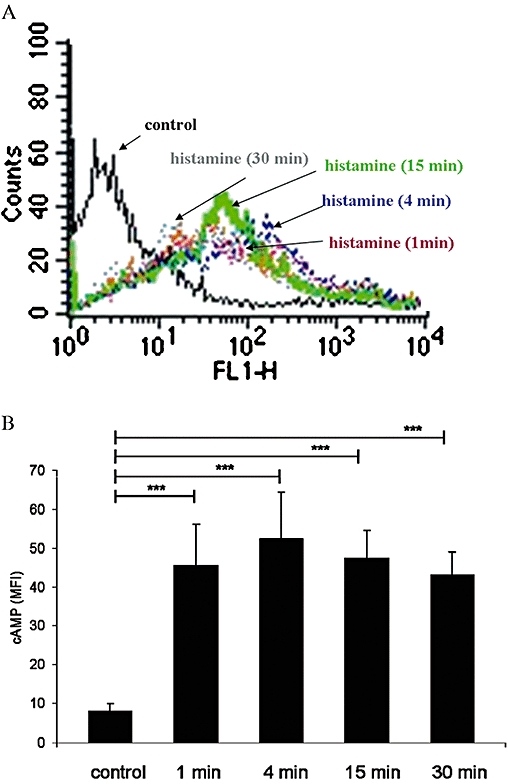

Histamine-induced intracellular cAMP levels in γδ T cells

Histamine is known to affect the intracellular cAMP levels in human dendritic cells and lymphocytes via H2 receptors and Gs proteins (Idzko et al., 2002). In order to characterize the functional expression of H2 receptors in human γδ T cells isolated from peripheral blood, intracellular cAMP levels after stimulation with histamine were determined by flow cytometry. A significant increase (P < 0.0001) in cAMP levels, as reflected by increases in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was observed 1 min after histamine treatment (Figure 6A). Moreover, cAMP levels reached a maximum after 4 min and remained high for at least 30 min after histamine stimulation (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Effect of histamine on intracellular cAMP levels in human peripheral blood γδ T cells. (A) Distribution of fluorescence intensity in control cells and γδ T cells stimulated with 1 µM histamine for 15 min is shown. Aliquots of cells were fixed and stained as described in Methods. The fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. Representative data of one experiment are shown; experiments were performed three times in triplicate. (B) Time course of cAMP levels after stimulation with 1 µM histamine. Experiments were repeated five times with γδ T cells isolated from different donors. Data are means ± SEM (n= 5) (***P < 0.0001). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

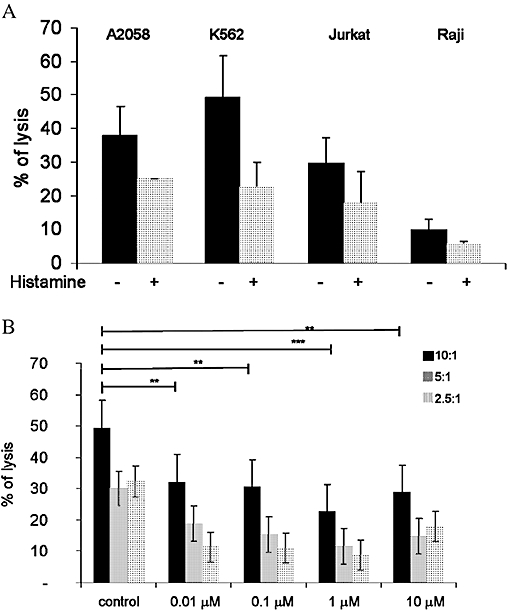

Histamine affects the cytotoxic activity of γδ T cells against tumour cells

We have previously shown that the activation of Gs protein coupled receptors and the up-regulation of cAMP lead to the down-regulation of cytotoxic responses in NK cells. In addition, γδ T cells are known to exhibit cytolytic activity towards different human tumour cell lines, such as the myeloid leukaemia cell line (K562), cutaneous malignant melanoma cells and the non-Hodgkin T cell line Jurkat (Sicard et al., 2001; Argentati et al., 2003). To better characterize the cytolytic activity of γδ T cells, in vitro radioactive assays were performed using different cell lines. Target cells were labelled for 1 h with chromium (100 µCi per 106 cells) and co-cultured for 4 h at 37°C with γδ T cells to allow spontaneous cytotoxicity. As shown in Figure 7A, although γδ T cells displayed cytolytic activity against all cell lines tested, their lytic capacity was highest against K562 cells. Therefore, this cell line was chosen for further experiments analysing the influence of histamine on the cytolytic activity of γδ T cells. Histamine significantly reduced the cytolytic capacity of γδ T cells against K562 cells, at all cell ratios (E:T) tested (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Cytotoxic activity γδ T cells from healthy donors towards tumour cell lines. (A) γδ T cells isolated from healthy donors were co-cultured with different tumour cell lines and the spontaneous cytolytic capacity was determined. (B) γδ T cells were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of histamine (0.01 µM–10 µM) and cytotoxicity against the chronic myeloid tumour cell line K562 was analysed. Cells were co-cultured in different effector: target ratios as indicated, on the right (E: T ratios: 10:1, 5:1 or 2.5:1). Data are means ± SEM (n= 3).

In order to find out which subtype of histamine receptor modulates cytotoxicity in γδ T cells, experiments with receptor-specific agonists and antagonists were performed. Agonists specific for H1 or H3 receptors did not affect the spontaneous lysis capacity of K562 cells by γδ T cells, whereas the H2 receptor-agonist dimaprit reduced the spontaneous lysis capacity of γδ T cells against K562 cells (Figure 8A). Moreover, while the H4 receptor antagonist did not prevent the histamine-induced effect on cytotoxicity, the H2 receptor antagonist cimetidine abolished this effect of histamine in γδ T cells (Figure 8B). These experiments suggest that the modulatory effect of histamine on γδ T cell mediated cytotoxicity requires activation of the H2 receptor subtype.

Figure 8.

Dimaprit inhibits the cytotoxic activity of human γδ T cells. (A) γδ T cells were stimulated with 1 µM histamine, 10 µM H1 receptor agonist HTMT, 10 µM H2 receptor agonist dimaprit and 0.01 µM H3 receptor agonist imetit and co-cultured with human myeloid cell line K562 in order to analyse the cytolytic activity. (B) γδ T cells were stimulated with 1 µM histamine in the presence or absence of 10 µM H4 receptor antagonist thioperamide, or 10 µM H2 receptor antagonist cimetidine and co-cultured with the human myeloid cell line K562 to analyse cytolytic activity. Data are means ± SEM (n= 3) (***P < 0.0001; **P > 0.005). ns, not significant.

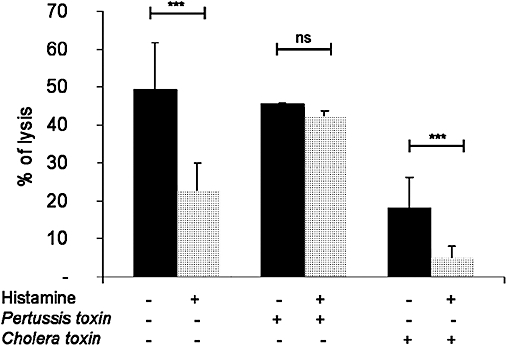

We next determined the involvement of different G proteins in the histamine modulation of cytotoxicity. Thus, γδ T cells were pretreated with the Gi protein inhibitor, Pertussis toxin and the Gs-activator, cholera toxin, and their cytotoxic activity against K562 cells examined (Figure 9). Pertussis toxin did not significantly alter the effect of histamine on cytotoxicity. On the contrary, pretreating γδ T cells with cholera toxin alone inhibited cytotoxicity by more than 50% compared with the histamine-untreated control cells. This inhibitory effect of the cholera toxin was further enhanced by histamine.

Figure 9.

Cytotoxic activity of human γδ T cells against tumour cells K562 is dependent on Gs proteins. γδ T cells were pre-incubated with or without cholera toxin (0.5 µg·mL−1) or Pertussis toxin (100 ng·mL−1) for 1 h at 37°C. Thereafter, γδ T cells were stimulated or not with histamine and co-cultured with K562 cells. Data are means ± SEM (n= 3) (***P < 0.0001). ns, not significant.

Discussion

Since its discovery in 1910, histamine has been regarded as one of the most important mediators in allergy and inflammation and is known to be involved in smooth muscle-stimulating, vasodepressor action and its involvement during anaphylaxis (Dale and Laidlaw, 1910). Although histamine is located in most body tissues, it is highly concentrated in the lungs, skin and gastrointestinal tract (Dunford et al., 2006), where it has been shown to regulate gastric acid secretion in the stomach and neurological transmitter functions (Haas et al., 2008; Ohtsu, 2008). In the central nervous system, histamine is involved in regulating drinking, body temperature, blood pressure and perceiving pain (Arrange et al., 1983; Hill et al., 1997). Moreover, histamine has also been described as an autocrine/paracrine or exogenous growth factor for cancer cells, e.g. malignant melanomas and leukaemia cells. In the case of chronic myeloid leukaemia, the secretion of histamine is the consequence of a leukaemia-specific oncogene (Aichberger et al., 2006). To better understand the role of histamine in the crosstalk between immune cells and tumour cells, we performed studies and co-culture experiments with human γδ T cells, isolated from peripheral blood.

By demonstrating that histamine stimulates actin polymerization and Ca2+ transients in a concentration-dependent manner and migration in a typical bell-shaped concentration curve, we showed that the increase in intracellular Ca2+ is due to mobilization from intracellular stores, inasmuch as it is insensitive to chelation of extracellular Ca2+. A long-lasting migration response requires a continuous interaction between migration-inducing ligands and their cell surface receptors to induce continuous cell activation of the ‘cell motor’ via actin polymerization. Therefore, a gradient of ligands, continuously available cell surface receptors and a very sensitive signal transduction mechanism are necessary to transmit the external signal to the internal processes leading to cellular movement. Thus, a low concentration of chemotactic ligands can activate and direct the cell over a long period of time. At high ligand concentrations, the receptors at the cell surface are very quickly occupied and consequently desensitized as well as internalized via endocytosis. In this case, the CI is low because ligands find no functional receptors at the cell surface and are not able to induce movement until either novel transcriptionally regulated receptors are synthesized or the internalized receptors are recycled (Tranquillo et al., 1988).

Histamine is a ligand for different G protein-coupled receptors. In order to demonstrate the participation of Gi proteins in these stimulated cell responses, experiments with Pertussis toxin were performed. This toxin selectively uncouples Gi proteins from the intracellular sites of receptors by ADP-ribosylation. Pretreating γδ T cells with Pertussis toxin blocked histamine-induced actin polymerization, Ca2+ transients and migration in γδ T cells, implying the involvement of Gi proteins in these cell responses. Principally, histamine binds to different receptor subtypes, H1, H2, H3 and H4 receptors. In the present work, RT-PCR revealed mRNA expression of histamine H1, H2 and H4 receptors, but not for H3 receptors, in γδ T cells. Moreover, expression of H1, H2 and H4 receptor proteins was shown by Western blot analysis. The involvement of the different receptors in these cell responses was dissected using specific receptor agonists and antagonists. Our experiments revealed that histamine regulates actin polymerization, Ca2+ transients and chemotaxis via H4 receptors, but provided no evidence for the involvement of H1, H2 or H3 receptors in these cell responses. This receptor-isoform-specific cell regulation is consistent with reports in eosinophils, mast cells and NK cells (Hofstra et al., 2003; Damaj et al., 2007). Therefore one can assume that histamine H4 receptors in γδ T cells activate Pertussis toxin-sensitive, heterotrimeric Gi proteins, which in turn dissociate into the GTP-a subunit and free βγ dimers. The latter activates phospholipase Cβ2 (Camps et al., 1992). This enzyme cleaves phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate into diacylglycerol and the inositol trisphosphate, which mobilizes Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Berridge and Imine, 1989). In leukocytes, Gi proteins regulate the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton independently of activated phospholipase C (Stossel, 1989). These Gi protein-coupled signalling pathways are essential components of migration response in different subtypes of leukocytes (Hauert et al., 2002).

Unlike classical chemotaxis-mediating receptors, such as chemokine receptors or complement C5a receptors, the coupling of different types of histamine receptors is pleiotropic, including interaction of H2 receptors with Gs proteins with consequent activation of adenylyl cyclase. Our cell studies combining histamine and selective receptor agonists or antagonists showed enhanced cAMP levels and, H2 receptor activation in γδ T cells. In different subtypes of leukocytes, e.g. NK cells and CD8+ T cells, the cytotoxicity response by cAMP has been reported to be inhibited (Wang et al., 1995). Our data show that the spontaneous cytolytic activity of human γδ T cells was prevented by histamine. Neither HTMT, nor imetit nor thioperamide, altered the spontaneous cytolytic capacity of γδ T cells, but it was inhibited by dimaprit, suggesting that H2 receptors may be involved in the inhibitory effect of histamine on the cytotoxicity of γδ T cells in human peripheral blood. Moreover, it has been shown that cholera toxin impairs cytotoxicity in αβ T lymphocytes and NK cells (Sugawara et al., 1993). Consistent with an earlier report (Sugawara et al., 1993), we found that the Gs protein activator cholera toxin inhibited the spontaneous cytotoxicity of γδ T cells, enhancing cAMP levels.

Infiltration by lymphocytes, macrophages, mast cells and neutrophils is a hallmark of inflammatory, defence and tissue repair reactions, which are often present in tumours. Various types of tumour-infiltrating macrophages and lymphocytes are considered as potential effectors of anti-tumour immunity and may interfere with tumour expression (Rosenberg, 2001). In this study, we have shown that histamine, which is present in the inflammatory and neoplastic microenvironment, induced the migration of human peripheral blood γδ T cells. In contrast, the spontaneous cytolytic effect of γδ T cells was prevented by histamine (Lazar-molnar et al., 2000; Sonobe et al., 2004). Neither HTMT, nor imetit nor thioperamide, altered the spontaneous cytolytic effect of γδ T cells, but it was inhibited by dimaprit, suggesting that H2 receptors may be involved in the inhibitory effect of histamine on cytotoxicity of human peripheral blood γδ T cells. Our data suggest that histamine contributes to the escape of tumour cells from immunological surveillance.

Acknowledgments

KT-F was a fellow of International Leibniz Research School Jena.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CI

chemotactic index

- dimaprit

S-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)isopthiourea

- FITC

fluoro-isothiocyanate

- H1, H2, H3, H4

histamine receptor subtypes

- HTMT

6-[2-(-imidazolyl)ethylamino]-N-(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)heptanecarboxamide dimaltate

- IL

interleukin

- NK

natural killer

- thioperamide

N-cyclohexyl-4-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)-1-piperidinecarbothioamide maleate salt (thioperamide)

Conflict of interests

None.

References

- Aichberger KJ, Mayerhofer M, Vales A, Krauth MT, Gleixner KV, Bilban M, et al. The CML-related oncoprotein BCR/ABL induces expression of histidine decarboxylase (HDC) and the synthesis of histamine in leukemic cells. Blood. 2006;108:3538–3547. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-028456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akdis CA, Simons FER. Histamine receptors are hot in immunopharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 2):S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argentati K, Re F, Serresi S, Tucci MG, Bartozzi B, Bernardini G, et al. Reduced number and impaired function of circulating gdT cells in patients with cutaneous primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:829–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrange JM, Garbarg M, Schwartz JC. Auto-inhibition of brain histamine release mediated by a novel class (H3) of histamine receptor. Nature. 1983;302:832–837. doi: 10.1038/302832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG. A study of antagonist affinities for the human histamine H2 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1011–1021. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, Steinle A, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, et al. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999;285:727–729. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Imine RF. Inositol phosphates and cell signalling. Nature. 1989;341:197. doi: 10.1038/341197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boullier S, Poquet Y, Debord T, Fournie J, Gougeon M. Regulation by cytokines (IL-12, IL-15, IL-4 and IL-10) of the Vg9Vd2 T cell response to mycobacterial phosphoantigens in responder and anergic HIV-infected person. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:90–99. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199901)29:01<90::AID-IMMU90>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner MB, McLean J, Dialynas DP, Strominger JL, Smith JA, Owen FL, et al. Identification of putative second T-cell receptor. Nature. 1986;322:145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimble MJ, Wallis DI. Histamine H1 and H2-receptors at a ganglionic synapse. Nature. 1973;246:156–158. doi: 10.1038/246156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Tanaka Y, Bloom BR, Brenner MB, et al. V gamma 2V delta 2 TCR-dependent recognition of non-peptide antigens and Daudi cells analyzed by TCR gene transfer. J Immunol. 1995;154:998–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps M, Carozzi A, Schnabel P, Scheer P, Parker PJ, Gierschik P. Isozyme-selective stimulation of phospholipase C-beta by G-protein beta-gamma subunits. Nature. 1992;360:684–686. doi: 10.1038/360684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Comparative biology of γδ T cells. Science Pogress. 2002;85:347–358. doi: 10.3184/003685002783238762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale HH, Laidlaw PP. The physiological action of b-imidazolethylamine. J Physiol. 1910;41:318–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1910.sp001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj BB, Becerra CB, Esber HJ, Wen Y, Maghazachi AA. Functional expression of H4 histamine receptor in human natural killer cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:7907–7915. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drutel G, Peitsaro N, Karlstedt K, Wieland K, Smit MJ, Timmerman H, et al. Identification of rat H3 receptor isoforms with different brain expression and signaling properties. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunford PJ, O'Donell N, Riley JP, Williams KN, Kalsson L, Thurmond RL. The histamine H4 receptor mediates allergic airway inflammation by regulating the activation of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:7062–7070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.7062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S. Calcium signalling in lymphocyte activation and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:690–702. doi: 10.1038/nri2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi M. Immunosurveillance and immunoregulation by γδ T cells. J Investigative Dermatol. 2006;126:25–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutzmer R, Diestel C, Mommert S, Kother B, Stark H, Wittmann M, et al. Histamine H4 receptor stimulation suppresses IL-12p70 production and mediates chemotaxis in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:5224–5232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas W, Pereira P, Tonegawa S. Gamma/delta T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:637–685. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas HL, Sergeeva OA, Selbach O. Histamine in the Nervous System. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1183–1241. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauert AB, Martinelli S, Marone C, Niggli V. Differentiated HL-60 cells are a valid model system for the analysis of human neutrophil migration and chemotaxis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:838–854. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyesi H, Tóth S, Molnár V, Fülöp KA, Falus A. Endogenous and exogenous histamine influences on angiogenesis related gene expression of mice mammary adenocarcinoma. Inflamm Res. 2008;56:37–38. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-0518-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberman RB. Natural killer (NK) cells and their possible roles in resistance against disease. Clin Immunol Rev. 1981;1:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SJ, Ganellin CR, Timmerman H, Schwartz JC, Shankley NP, Young JM, et al. International union of pharmacology. XIII. Classification of histamine receptors. Pharmacological Rev. 1997;49:253–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra CL, Desai PJ, Thrumond RL, Fung-Leung W. Histamine H4 receptor mediates chemotaxis and calcium mobilization of mast cells. JPET. 2003;305:1212–1221. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idzko M, la Sala A, Ferrari D, Panther E, Herouy Y, Dichmann S, et al. Expression and function of histamine receptors in human monocyte derived dendritic cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:839–846. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabelitz D. Human γδ T cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunology. 1993;102:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000236544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabelitz D, Glatzel A, Wesch D. Antigen recognition by human γδ T lymphocytes. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2000;122:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000024353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinet JP. The high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI): from physiology to pathology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:931–972. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagadari M, Truta-Feles K, Lehmann K, Berod L, Ziemer M, Idzko M, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits the cytotoxic activity of NK cells: involvement of Gs protein-mediated signaling. Int Immunol. 2009;21:667–677. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar-Molnar E, Hegyesi H, Toth S, Darvas ZS, Laszlo V, Szalai CS, et al. Biosynthesis of interleukin-6, an autocrine growth factor for melanoma, is regulated by melanoma-derived histamine. Blood. 2000;10:25–28. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leurs R, Chazot PL, Shenton FC, Lim HD, de Esch JP. Molecular and biochemical pharmacology of the histamine H4 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:14–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara M, Tamura T, Ohmori K, Hasegawa K. Histamine H1 receptor antagonist blocks histamine-induced proinflammatory cytokine production through inhibition of Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C, Raf/MEK/ERK and IKK/I kB/NF-kB signal cascades. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:433–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki Y, Tanimoto A, Hamada T, Sasaguri Y. Histidine decarboxylase expression as a new sensitive and specific marker for small cell lung carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:72–78. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000044485.14910.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata M, Smyth MJ, Norihisa Y, Kawasaki A, Shinkai Y, Okumura K, et al. Constitutive expression of pore-forming protein in peripheral blood γδ T cells: implication for their cytotoxic role in vivo. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1877–1880. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsu H. Progress in allergy signal research on mast cells: the role of histamine in immunological and cardiovascular disease and the transporting system of histamine in the cell. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;106:347–353. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fm0070294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panther E, Idzko M, Herouy Y, Rheinen H, Gebicke-Haerter PJ, Mrowietz U, et al. Expression and function of adenosine receptors in human dendritic cells. FASEBJ. 2001;15:1963–1970. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0169com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe S, Ruggiero A, Tortora G, Ciardiello F, Garbi C, Yokozaki H, et al. Flow-cytometric detection of the RI alpha subunit of type I cAMP-dependent protein kinase in human cells. Cytometry. 1994;15:73–79. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990150112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JF, West GB. Histamine in tissue mast cells. J Physiol. 1952;117:72–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411:380–384. doi: 10.1038/35077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selin LK, Santolucito PA, Pinto AK, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Welsh RM. Innate immunity to viruses: control of vaccinia virus infection by γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:6784–6794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicard H, Saati TA, Delsol G, Fournier JJ. Synthetic phosphoantigens enhance human Vg9Vd2 T lymphocytes killing of non-Hodgkin's B lymphoma. Mol Medicine. 2001;7:711–722. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonobe Y, Nakane H, Watanabe T, Nakano K. Regulation of Con A-dependent cytokine production from CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes by autosecretion of histamine. Inflamm Res. 2004;53:87–92. doi: 10.1007/s00011-003-1227-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stossel TP. From signal to pseudopod. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara S, Kaslow HR, Dennert G. CTX-B inhibits CTL cytotoxicity and cytoskeletal movements. Immunopharmacology. 1993;26:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(93)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranquillo RT, Lauffenburger DA, Zigmond SH. A stochastic model for leukocyte random motility and chemotaxis based on receptor binding fluctuations. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:303–309. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Fiscus RR, Yang L, Mathews HL. Suppression of the functional activity of IL-2-activated lymphocytes by CGRP. Cell Immunol. 1995;162:105–113. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel P, Shijaei H, Schittek B, Gieseler F, Wollenberg B, Kalthoff H, et al. Lysis of a broad range of epithelial tumor cells by human γδ T cells: Involvement of NKG2D ligands and T-cell receptor-versus NKG2D-dependent recognition. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66:320–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakabi K, Kawashima J, Kato S. Ghrelin and gastric acid secretion. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6334–6338. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampeli E, Tiligada E. The role of histamine H4 receptor in immune and inflammatory disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]