Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid is a potent vasoconstrictor that contributes to cerebral ischaemia. An inhibitor of 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthesis, TS-011, reduces infarct volume and improves neurological deficits in animal stroke models. However, little is known about how TS-011 affects the microvessels in ischaemic brain. Here, we investigated the effect of TS-011 on microvessels after cerebral ischaemia.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

TS-011 (0.3 mg·kg−1) or a vehicle was infused intravenously for 1 h every 6 h in a mouse model of stroke, induced by transient occlusion of the middle cerebral artery occlusion following photothrombosis. The cerebral blood flow velocity and the vascular perfusion area of the peri-infarct microvessels were measured using in vivo two-photon imaging.

KEY RESULTS

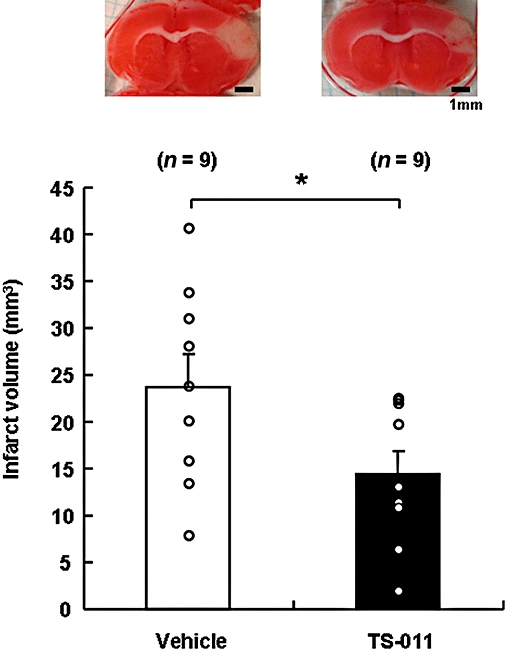

The cerebral blood flow velocities in the peri-infarct microvessels decreased at 1 and 7 h after reperfusion, followed by an increase at 24 h after reperfusion in the vehicle-treated mice. We found that TS-011 significantly inhibited both the decrease and the increase in the blood flow velocities in the peri-infarct microvessels seen in the vehicle-treated mice after reperfusion. In addition, TS-011 significantly inhibited the reduction in the microvascular perfusion area after reperfusion, compared with the vehicle-treated group. Moreover, TS-011 significantly reduced the infarct volume by 40% at 72 h after middle cerebral artery occlusion.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

These findings demonstrated that infusion of TS-011 improved defects in the autoregulation of peri-infarct microcirculation and reduced the infarct volume. Our results could be relevant to the treatment of cerebral ischaemia.

Keywords: 20-HETE, ischaemia, microcirculation, peri-infarct, two-photon microscopy

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, over ten million people worldwide suffer from strokes per year and the number of stroke patients will increase further in the future (Mackay and Mensah, 2004). A large number of stroke patients suffer permanent neurological deficits that impair their quality of life.

Substantial evidence suggests that the microcirculation in the peri-infarct region is an important target in the treatment of cerebral ischaemia, including the improvement of neurological deficits (del Zoppo and Mabuchi, 2003; Hossmann, 2006). The impairment in microcirculation after focal cerebral ischaemia contributes to the development of cerebral ischaemic damage (Hallenbeck and Dutka, 1990). This microcirculatory impairment is caused by several factors such as the mechanical obstruction of microvessels by blood constituents (del Zoppo et al., 1991; Garcia et al., 1994a), fibrin formation (Okada et al., 1994), the swelling of endothelial cells and astrocytes (Garcia et al., 1994b), and an increase in the vascular tone arising from an imbalance between vasoconstrictors and vasodilators (Spatz et al., 1996). Recent studies have shown that the improvement of impaired microcirculation in the peri-infarct region by an endothelin receptor antagonist or oestradiol can reduce the infarct volume and improve neurological deficits (Patel et al., 1996; Lehmberg et al., 2003; Ardelt et al., 2007), indicating that microcirculation in the peri-infarct region can be regarded as a relevant target of treatment.

The viability of the peri-infarct tissue depends on the residual cerebral blood flow (CBF) during and after ischaemia in animal models (Ayata et al., 2004). Because the CBF in the peri-infarct region is still maintained, the neurons in this region are functionally inactive but remain structurally intact during the acute phase of cerebral ischaemia (Astrup et al., 1981; Hossmann, 2006). Therefore, the neurons in the peri-infarct region might potentially be salvaged with effective treatment and this region should be a primary therapeutic target for reducing damage after stroke. The regulation of the CBF is critical in maintaining the recovery of neural function. Cerebral autoregulation is the ability of the cerebrovascular system to maintain a constant CBF during arterial blood pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure changes (Lassen, 1959). Under pathological conditions such as acute ischaemic stroke and severe head injury, CBF autoregulation is impaired (Paulson et al., 1990). This impairment of CBF autoregulation causes attenuation of vasoreactivity, disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and formation of oedema (Paulson et al., 1990; Cipolla and Curry, 2002).

20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) is one of the cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid (Roman, 2002) and is a potent vasoconstrictor of cerebral microvessels (Harder et al., 1994), playing an important role in the autoregulation of CBF (Gebremedhin et al., 2000). Previously, we reported an elevation of the brain and plasma 20-HETE levels in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model (Tanaka et al., 2007). Such increased levels of 20-HETE might be associated with the impairment of cerebral autoregulation after stroke. A selective inhibitor of 20-HETE synthesis, N-(3-chloro-4-morpholin-4-yl) phenyl-N′-hydroxyimido formamide (TS-011), reduced the elevation of brain and plasma 20-HETE levels after ischaemia, reducing the infarct volume and improving the neurological outcome in rat and monkey stroke models (Miyata et al., 2005; Omura et al., 2006; Tanaka et al., 2007).

However, little is known about the mechanism of action of TS-011 because of technical limitations in assessing microvascular dynamics in vivo. Two-photon laser-scanning microscopy (TPLSM) is an ideal tool for high-resolution fluorescence imaging in intact organs of living animals (Helmchen and Kleinfeld, 2008) as it provides deeper tissue penetration, higher image contrast and less photobleaching and photodamage to the tissue, than conventional confocal microscopy (Theer et al., 2003; Rubart, 2004; Nemoto, 2008). Because of these properties, TPLSM is especially suitable for long-term measurement of the change in blood flow in a single and same microvessel. Therefore, we used TPLSM to image the cortical microvasculature and measure the vasodynamics of microvessels (Nishimura et al., 2006; Zhang and Murphy, 2007).

To explore the possibility that a reduction of 20-HETE levels could improve defects of peri-infarct microcirculation, we evaluated the actions of TS-011 on microvessels in a mouse transient MCAO model using TPLSM, in vivo. We found that TS-011 improved the peri-infarct microcirculation after ischaemia and reduced the infarct volume.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the guidelines published by the National Institutes of Health and the Japanese Experimental Animal Research Association and were approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Animal Experimentation of the National Institutes for Natural Sciences.

Preparation of the mouse model

The studies were performed using 58 male C57BL/6J mice (8 weeks old, Japan SLC Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) weighing 20–26 g. The mice were randomly divided into three groups for the measurements of blood flow velocity, microvascular perfusion area and infarct volume. Anaesthesia was induced with 3% isoflurane and was maintained with 1% isoflurane during the experiments. In the blood flow velocity experiments, the mice were under anaesthetic for approximately 3 h in order to prepare the cranial window and collect data up to the second scan at 1 h after reperfusion. At this point anaesthesia was withdrawn and subsequently a short (10 min) anaesthesia used to collect data at the 2, 4, 7 and 24 h time points after reperfusion. For the microvascular perfusion area experiments, the mice were continuously anesthetized for three and a half hours. For experiments determining infarct volume, the mice were anesthetized to induce MCAO and for the first hour of reperfusion. All mice were freely breathing under anaesthesia. We confirmed that isoflurane anaesthesia had no effect on mean arterial blood pressure and heart rate in mice in preliminary experiments (data not shown). None of the mice died under anaesthetic. The rectal temperature was maintained at 37°C using a heating pad (Fine Science Tools Inc., North Vancouver, Canada). A silicon tube (inner diameter: 0.5 mm, outer diameter: 1.0 mm; AS ONE, Osaka, Japan) was implanted in the right jugular vein for drug infusion. This tube was subcutaneously externalized through the dorsal neck to allow drug infusion to be performed in conscious animals. A cranial window (3 mm in diameter) for observing the microvessels was made over the left primary somatosensory cortex (the site of the peri-infarct area) leaving the dura mater intact. After the removal of the skull, artificial cerebral spinal fluid containing 150 mmol·L−1 NaCl, 2.5 mmol·L−1 KCl, 1 mmol·L−1 MgCl2, 2 mmol·L−1 CaCl2, 10 mmol·L−1 HEPES and 10 mmol·L−1 glucose (pH 7.4) in Tris-base was added over the dura mater. The cranial window was then sealed with a cover glass. To reduce movement artefacts, a metal ring surrounding the cranial window was attached to the skull with dental acrylic cement, and artificial cerebral spinal fluid was used to keep this region moist during the experiments. In the experiment for blood flow velocity, these procedures were performed before the first time-lapse imaging. In the experiment for perfusion area, these procedures were performed just before MCAO.

Transient MCAO model

Transient occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) was produced by a laser-induced photochemical reaction using a modified procedure described previously (Yao et al., 2002). The skin was cut between the left eye and ear, exposing the skull and left temporal muscle. The temporal muscle was retracted until the distal part of the left MCA was observed. The exposed tissues were kept moist with saline. A krypton laser (643-Y-A01; Melles Griot Inc., Albuquerque, NM, USA), emitting at a wavelength of 568 nm and power of 6 mW, was used to irradiate the MCA. The laser beam was positioned with a mirror and focused with a convex lens (KPX082AR.14; Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) onto the distal MCA. Laser irradiation started immediately after the intravenous administration of a photosensitizing Rose Bengal dye solution (20 mg·kg−1) for 2 min. After 4 min of irradiation, the laser beam was moved to an additional site just proximal to the first irradiated site and another 4 min of irradiation was performed. Thirty minutes after the second irradiation, a Q-switched, frequency-tripled yttrium aluminium garnet laser operating at a wavelength of 355 nm (8 mW; 15 Hz; average power, 1.15 W·cm−2) (Minilite II; Continuum Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was focused with a 30 cm focal length cylindrical lens (CKX 300; Newport Corporation) and positioned with a mirror enveloping the occluded distal MCA, which had been induced by krypton laser irradiation. The occluded MCA was irradiated with the yttrium aluminium garnet laser for 4 min to allow reperfusion. All wounds were disinfected with Hibitane at the time of surgery. The temporal muscle was put back in its normal position, and the skin was closed with sutures after surgery.

The mice used for measurement of infarct volume were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated at 72 h after reperfusion. The brains were removed and cut into seven 1 mm thick coronal sections using a Rodent Brain Matrix slicer (RBM-2000C; ASI Instruments, Warren, MI, USA). The sections were immersed in a 2% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride at 37°C for 30 min. The infarct area in each section was measured using NIH-Image analysis software, version 1.62 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and the area was determined using a method that corrects for oedema (Lin et al., 1993), using the following formula:

|

The total infarct volumes were calculated by investigators who were unaware of the treatments in each group.

In vivo TPLSM

Anaesthesia was induced with 3% isoflurane and maintained with 1% isoflurane during scanning. The withdrawal reflex after footpad pinching was used to monitor the depth of the anaesthesia. Images of the vessels stained using the fluorescent dyes were visualized using a TPLSM (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) coupled with a mode-locked Ti-sapphire laser (pulse width of <100 fs, 80 MHz repetition frequency at a wavelength of 740 nm) (Mai Tai HP; Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA, USA). The excitation light was focused using a water-immersion objective lens (20×; 0.95 numerical aperture) (IR-LUMPlanFl, Olympus). The emitted fluorescence was divided into long (=570 nm) and short wavelengths using a dichroic mirror (570 nm; Olympus). The imaged area on which we focused is shown in Figure 1A.

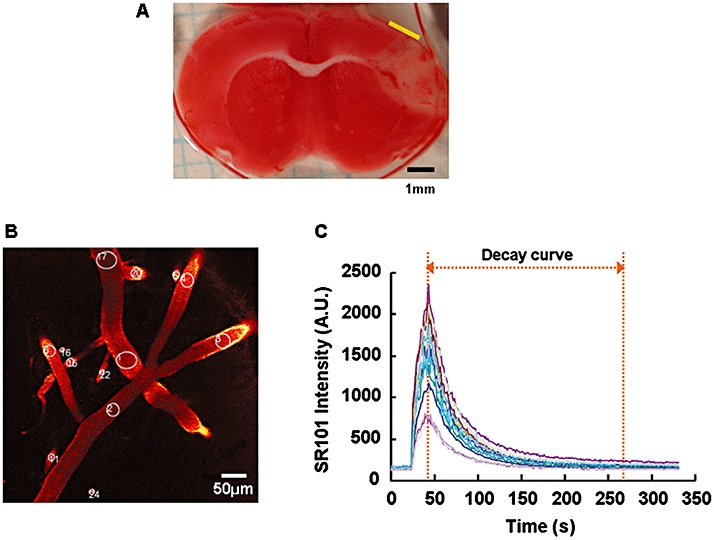

Figure 1.

A) Representative coronal section of mouse brain stained with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride. The imaged area we focused by two-photon laser-scanning microscopy is indicated by the yellow bar. The adjacent, less stained cortex was the area infarcted at 72 h after reperfusion. B) Representative two-photon laser-scanning microscopy image of cerebral microvessels at a depth of 75 µm, which have been stained with SR101. The regions of interest for the measurement of the blood flow velocities in the microvessels are circled and numbered. C) SR101 intensity curves for the regions of interest of each microvessel shown in B. The AUC was calculated within the range of the decay curve indicated in this graph. The SR101 intensity was expressed as an arbitrary unit (A.U.).

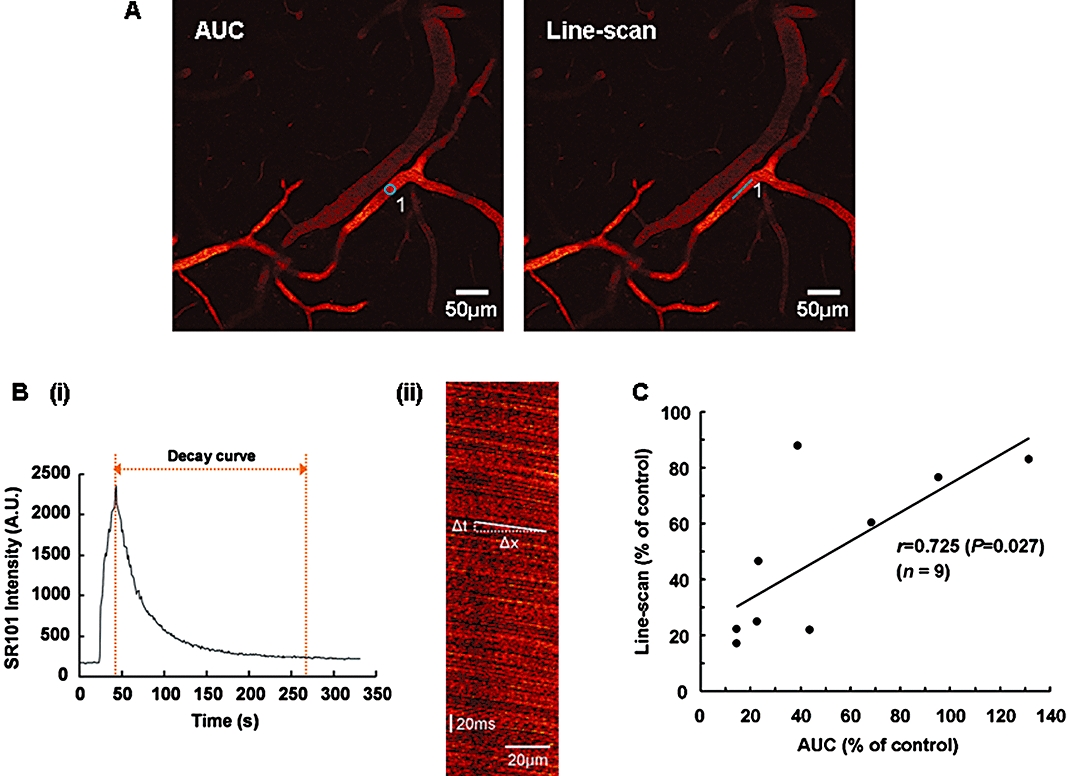

To measure the blood flow velocity in the microvessels, 25 µL of sulforhodamine 101 (SR101, 0.4 mmol·L−1) was injected into the jugular vein using an infusion pump (Model 11; Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA, USA) over a 30 s period for the fluorescent labelling of the blood plasma. Time-lapse imaging using TPLSM was performed to acquire the time-dependent changes in SR101 intensity. During each time-lapse imaging, 300 consecutive frames (512 × 512 pixels) were acquired at a rate of 1.1 s per frame. These frames were taken at around a depth of 75 µm, which corresponds to cortical layer 1 and the upper part of layer 2/3. The SR101 injection was started at 25 s after the initiation of time-lapse imaging. These procedures were performed before and during MCAO and 1, 2, 4, 7 and 24 h after reperfusion by investigators who were unaware of the treatments in each group. The regions of interest (ROI) for measurement of the blood flow velocity were placed over microvessels (over 10 µm in diameter) in one of the sequence images (Figure 1B). Then, the time-dependent change in SR101 intensity in each ROI was analysed using FV10-ASW 1.5 Viewer software (Olympus), and the SR101 intensity curve for each ROI was acquired (Figure 1C). In this curve, the decay curve after the peak represents the disappearance of the SR101 intensity. The blood flow velocity was defined as the velocity of the disappearance of the SR101 intensity. The area under the decay curve (AUC) of the SR101 intensity at each time point was calculated, and each AUC value was normalized with the control value obtained before MCAO. Because the AUC value was negatively correlated with the disappearance of SR101, the normalized AUC value was converted into its reciprocal and was used as a substitute for the blood flow velocity. To confirm that this method using a SR101 decay curve is appropriate for measuring blood flow velocity, we compared this method using the SR101 decay curve with a conventional method (line-scan method: Schaffer et al., 2006) with regard to the measurement of blood flow velocity. Briefly, time-lapse imaging was performed to acquire the time-dependent change in the SR101 intensity, and SR101 injection was started at 25 s after the initiation of time-lapse imaging. The SR101 was injected by the same method as described above and the ROI for the method using the SR101 decay curve was placed over a microvessel (Figure 2A, AUC). Then, the SR101 intensity curve in the ROI was acquired (Figure 2B, i) and the blood flow velocity was calculated as described above. Subsequently, the ROI for the line-scan method was placed over the same microvessels as those selected for use with our method (Figure 2A, Line-scan). After the disappearance of the former injection of SR101, additional SR101 was injected in the same manner as described above, and repetitive line-scans were performed at 1.5 ms per line. The blood flow velocity was determined by repetitive line-scans performed along the central axis of the microvessel as previously reported (Schaffer et al., 2006). To calculate the blood flow velocity, a line was fit to the linear shadows produced by the red blood cells, and the change in position of the cells over time (Δx/Δt) was calculated (Figure 2B, ii). These procedures were performed before and after MCAO.

Figure 2.

A) Representative two-photon laser-scanning microscopy images of cerebral microvessels at a depth of 75 µm, which have been stained with SR101. The regions of interest for the measurements by the method using the SR101 decay curve and the line-scan method are indicated by the circle (AUC, left panel) and the line (Line-scan, right panel) respectively. B) (i) Representative SR101 intensity curve within the regions of interest. (ii) Representative line-scan image showing the linear shadows produced by negatively stained red blood cells. The blood flow velocity was calculated as the slope (Δx/Δt). C) Relation between the middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced reductions in blood flow velocities as measured by the method using the SR101 decay curve (AUC) and the line-scan method. A statistically significant correlation between the two methods was observed using Pearson product–moment correlations.

To measure the microvascular perfusion area affected by vascular dilation or constriction, 0.1 mL of 1% fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled dextran (70 kDa) in saline was injected into the jugular vein for visualization of the microvessels before scanning. A z-series scan starting at several tens of micrometers below the pial surface was performed in 1 µm steps, and 76 consecutive frames (with a depth range of 75 µm) were acquired for each scan. Each frame was taken at 1.1 s intervals. These 76 consecutive frames were stacked along the z-axis to observe all the vessels within the scanning area. This z-stacked image was binarized into fluorescent dye-stained and non-stained areas using Adobe Photoshop 5.5 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The stained area in the binarized images was then measured using MacSCOPE ver 2.59 (Mitani Co. Ltd, Fukui, Japan), and these values were normalized with the control values obtained for the first z-series scan. This first scanning was performed before drug administration (corresponding to 1 h after reperfusion). The second scanning was started at the same time as the drug administration and the subsequent z-series scans were successively performed every 15 min until 120 min after drug administration. TS-011 or the vehicle was administered as a 1 h infusion after reperfusion. These evaluations were performed by investigators who were unaware of the treatments in each group. None of the mice exhibited any abnormalities during the experiments.

Drug administration

TS-011 was dissolved in 11% sulphobutylether-β-cyclodextrin. TS-011 (0.3 mg·kg−1) or the vehicle was administered as a 1 h infusion at a rate of 10 mL·kg−1·h−1 every 6 h until 24 or 72 h after reperfusion for the blood flow velocity or infarct volume measurements respectively. In all these experiments, the mice were randomly assigned to treatment. This procedure was performed using a free-moving cannulation system (TFM-170C; Sugiyama-gen Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) attached to a cannula swivel (375/22; Instech Laboratories, Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) to allow the mice to move freely within their cages.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean values ± SEM. A correlation analysis comparing the blood flow velocities calculated by the method using the SR101 decay curve and the line-scan method was performed by determining the Pearson product moment correlations. The significance of differences in the mean blood flow velocities and infarct volumes between the groups was examined using a Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The significance of differences between the time-dependent curves for the microvascular perfusion areas in each group during the period of measurement was examined using a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (anova). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Materials

Materials were provided by the suppliers shown: isoflurane (Abbott Japan, Tokyo), sulphobutylether-β-cyclodextrin (CyDex Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Lenexa, KS, USA), SR101 (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo), 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, Osaka, Japan) and TS-011 (Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Saitama, Japan). The drug and molecular target nomenclature follows Alexander et al. (2009).

Results

Measurement of blood flow velocities by the method using the SR101 decay curve and the line-scan method

We selected microvessels greater than 10 µm in diameter for the measurement of blood flow velocities according to a previous study (Stefanovic et al., 2008) (Figure 1B). When determining the region of interest, we traced the microvessels back to identifiable arteries that had branched from the MCA; therefore, we considered the microvessels examined in this study to be arterioles. We focused on the microvessels in the peri-infarct region that is potentially salvageable with effective treatment. The purpose of this study was to estimate the effect of TS-011 on the blood flow velocities in a number of microvessels in this region. Therefore, we needed to detect changes in the blood flow velocities in a number of microvessels in the peri-infarct region simultaneously. Consequently, we employed the method using the SR101 decay curve. To confirm the validity of this method for the measurement of blood flow velocity, we calculated and compared the MCAO-induced reductions in blood flow velocities in identical microvessels by both the method using the SR101 decay curve and the line-scan method (Figure 2A, AUC and Line-scan). The values calculated using the two methods were significantly correlated (r= 0.725, P= 0.027, Pearson product moment correlations, n= 9, Figure 2C). In addition, to confirm that our method can detect changes in the blood flow velocities induced by a vasodilator, the effect of acetazolamide on the blood flow velocity in normal mice was examined. A previous report showed that acetazolamide at a dose of 7 mg·kg−1 increased CBF in mice (Lacombe et al., 2005). In the present study, the mice were intravenously treated with acetazolamide at the same dose. Acetazolamide increased the blood flow velocity to 116.4 ± 1.5% of the control value immediately after treatment. These results suggest that our measurement method can be used to detect changes in blood flow velocities in vivo with an accuracy similar to that of the line-scan method.

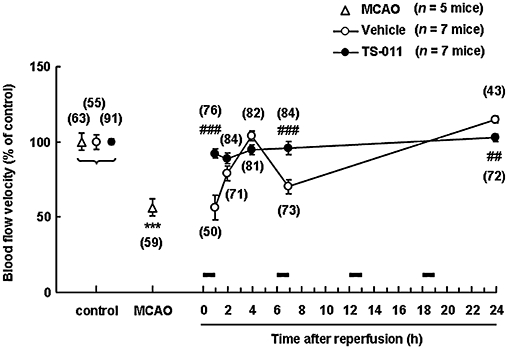

Effect of TS-011 on blood flow velocities

We next examined the effect of TS-011 on CBF, using the SR101 decay curve. The average diameter of the measured microvessels in this study was 27.3 ± 16.7 µm (mean ± SD, n= 984 in 19 mice). Blood flow velocity was defined as the bleaching speed of the fluorescent dye, as described in the Methods section (Figure 1C). To determine the effect of MCAO on the blood flow velocities in our system, we measured the blood flow velocities in the peri-infarct region before and during MCAO. The blood flow velocity during MCAO was significantly reduced to about half that of the control values obtained pre-occlusion (Figure 3). Then, to evaluate the effect of TS-011 on the blood flow velocities during ischaemic stroke, we measured the blood flow velocities in the peri-infarct region after reperfusion. TS-011 (0.3 mg·kg−1) or the vehicle was intravenously administered as a 1 h infusion every 6 h. In the vehicle-treated group, the blood flow velocities at 1 and 2 h after reperfusion were clearly decreased, compared with the control values (Figure 3). The blood flow velocity at 4 h after reperfusion returned to pre-occlusion values, but fell again at 7 h after reperfusion. Conversely, the blood flow velocity at 24 h after reperfusion increased slightly, relative to the control value. In the TS-011-treated group, the blood flow velocities were almost equivalent to the pre-occlusion value at all time points after reperfusion (Figure 3). TS-011 at a dose of 0.3 mg·kg−1 inhibited the reduction in the blood flow velocities at 1 and 7 h after reperfusion (P < 0.001, Student's t-test). In addition, TS-011 inhibited the increase in the blood flow velocity at 24 h after reperfusion (P < 0.01, Student's t-test).

Figure 3.

Effect of TS-011 on blood flow velocities in a mouse transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model. TS-011 (0.3 mg·kg−1) or the vehicle was intravenously administered as a 1 h infusion at 0 (immediately after reperfusion), 6, 12 and 18 h after reperfusion. The values for the blood flow velocities during MCAO, 1, 2, 4, 7 and 24 h after reperfusion are expressed as a percentage of the corresponding control value obtained before MCAO (100%). The times of the TS-011 infusions are shown by the black bars. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of vessels studied per group. ***P < 0.001, significantly different from the control value (Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons); ###P < 0.001, ##P < 0.01, significantly different from the vehicle-treated group (Student's t-test).

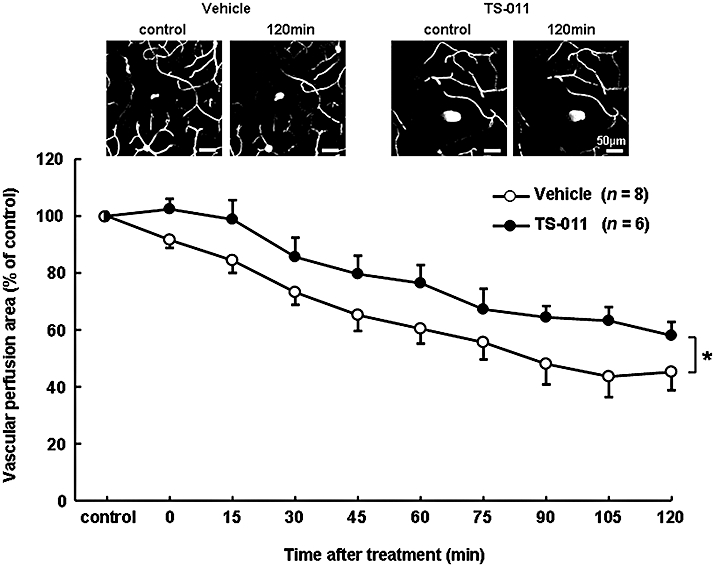

Effect of TS-011 on the microvascular perfusion area

As 20-HETE is a potent vasoconstrictor of cerebral microvessels, the effect of TS-011 on the microvascular perfusion area was examined in a mouse transient MCAO model, by measuring the fluorescent dye-stained area, as described in the Methods section. We acquired two z-stacked images (Figure 4, upper panels) from one mouse. In the vehicle-treated group, there was a slow fall in the microvascular perfusion area, over the 120 min after administration (n= 8, Figure 4). Treatment with TS-011 decreased this fall at all times of sampling (n= 6, P < 0.05, two-way repeated measures anova), indicating that TS-011 protected the microvascular perfusion area from the loss observed in vehicle-treated mice.

Figure 4.

Effect of TS-011 on the microvascular perfusion area after reperfusion in a mouse transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Representative binarized z-stacked images before (corresponding to 1 h after reperfusion) and 120 min after treatment with the vehicle or TS-011 are shown in the upper panels. TS-011 (0.3 mg·kg−1) or the vehicle was administered as a 1 h infusion after the first scanning. The values for the microvascular perfusion area at various time points are expressed as a percentage of the corresponding control value obtained at first scanning (100%). The differences between the two time-courses was analysed with a two-way repeated measures anova; *P < 0.05, significantly different from the vehicle-treated group. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of z-stacked images analysed per group.

Effect of TS-011 on the infarct volume

We examined the effect of TS-011 on the infarct volume at 72 h after reperfusion in a mouse transient MCAO model. As shown in the two sections in the upper half of Figure 5, the infarct volume was reduced and the summary data showed that TS-011, at a dose of 0.3 mg·kg−1, reduced the infarct volume by almost 40% (P < 0.05, Student's t-test).

Figure 5.

Effect of TS-011 on infarct volume in a mouse transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Representative images of the 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride-stained sections are shown in the upper panels. The infarct volumes were determined using 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride-staining at 72 h after reperfusion. TS-011 (0.3 mg·kg−1) or the vehicle was administered as a 1 h infusion every 6 h until 72 h after reperfusion. *P < 0.05 significantly different from the vehicle-treated group (Student's t-test). The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of animals studied per group.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we investigated the effect of TS-011 on CBF in the peri-infarct microcirculation after MCAO in mice, using in vivo TPLSM. We found that TS-011 inhibited the variation of CBF velocities and maintained the peri-infarct microcirculation at the control level for up to 24 h after reperfusion. Moreover, TS-011 reduced the infarct volume at 72 h after reperfusion. This improvement in blood flow in the peri-infarct microcirculation is thought to be one of the mechanisms by which TS-011 reduces the infarct volume in animal stroke models.

Two-photon laser-scanning microscopy is an efficient tool for imaging the cortical microvasculature and its vasodynamics. The blood flow velocities of penetrating arterioles have been measured using TPLSM with fluorescein-dextran labelled plasma in local occlusion of single artery or rat transient MCAO model (Schaffer et al., 2006; Zhang and Murphy, 2007). These earlier studies measured the blood flow velocity directly using the line-scan method, but it is difficult to scan many vessels simultaneously using this method. In contrast, the method we used can measure blood flow velocities in many vessels simultaneously, although its time-resolution is not as high as that of the line-scan method. In this experiment, we defined the blood flow velocity as the speed at which the SR101 intensity disappeared. As shown in Figure 1C, the SR101 intensity curves for each ROI were acquired at each time-lapse imaging. The decay curve after the peak intensity represents the outflow of SR101. In addition, as shown in Figure 2C, the method using the SR101 decay curve was confirmed to be a valid means of measuring the blood flow velocity with an accuracy comparable with that of the line-scan method. While the line-scan method can detect the movement of red blood cells directly, our method can detect the change in the SR101 intensity, which is thought to reflect the flow of blood plasma. Therefore, we considered the rate of decay of the SR101 intensity to represent the blood flow velocity. Nevertheless, the possibility that the disappearance of SR101 was influenced by factors other than blood flow velocity, such as leakages of SR101 or elimination of the dye by renal clearance, could be considered. The leakage of SR101 through the BBB may promote the disappearance of SR101 from the microcirculation, which would result in an apparent increase in the blood flow velocity when measured using this method. Actually, as shown in Figure 3, TS-011 improved the blood flow velocity at 1 and 7 h after reperfusion. On the other hand, TS-011 improved the infarct volume as shown in Figure 5. In addition, TS-011 has been previously reported to have beneficial effects on cerebral ischaemic injury in rats and monkeys (Omura et al., 2006; Tanaka et al., 2007). These results would suggest that TS-011 is unlikely to promote BBB disruption. Therefore, we concluded that the leakage of SR101 through the BBB was not involved in the beneficial effect of TS-011 on the blood flow velocity observed in this study. On the other hand, the elimination of the SR101 dye by renal clearance could also seemingly increase the blood flow velocity. However, we measured the decay in the SR101 intensity within the ROI on each microvessel over a short period of time (within several minutes) during each time-lapse imaging session. Therefore, we considered that the influence of renal clearance on the measurement of the blood flow velocity to be minimal using this method. Further studies are needed to confirm the influence of TS-011 on renal clearance.

We examined the kinetics of blood flow in the peri-infarct microvessels in a mouse transient MCAO model. The blood flow velocities in the peri-infarct microcirculation varied widely and decreases were observed at 1 and 7 h after reperfusion, whereas an increase was observed at 24 h after reperfusion. The CBF in the peri-infarct region was reportedly reduced after reperfusion in a focal ischaemic stroke model (Mies et al., 1991; van Dorsten et al., 2002; Bardutzky et al., 2007). Moreover, the CBF in the peri-infarct zone decreased transiently at 3 h after ischaemia and then increased again in a rat model (Takamatsu et al., 2000), while another study reported that the peri-infarct microcirculation varied during 4 h of MCAO in a rat model (Dawson et al., 1997). These authors observed both a decrease and an increase, at different times, in the cerebral circulation. In addition, an increase in CBF at 24 h after MCAO has also been reported using magnetic resonance imaging in a rat transient MCAO model (Wang et al., 2002). The cerebral hyperaemia observed during the late reperfusion period is thought to be a ‘luxury’ perfusion caused by an impairment of autoregulation (Wang et al., 2002). The CBF kinetics described above are consistent with our observations. Previously, we reported that the brain 20-HETE level increased with MCAO and reached a significantly higher level, compared with the pre-MCAO level, within 4 h after reperfusion in rats (Tanaka et al., 2007). The impairments of blood flow velocities observed at several time points after reperfusion in this study might be involved in the elevation of the 20-HETE level. The results of this study suggest that the improvement in the peri-infarct microcirculation induced by TS-011 exerts a beneficial effect on the ischaemic insults. However, the effect of TS-011 on CBF in the present study was not consistent with a previous report showing that the protective effects of this drug were not associated with an increase in CBF (Renic et al., 2009). The reason for this discrepancy might be that Renic et al. did not measure the CBF in microvessels but rather measured the total CBF, including blood flow through larger vessels, using laser Doppler flowmetry. In contrast, we used TPLSM in this study to focus on the microvessels and to measure the CBF in the microvessels specifically. Consequently, we were able to observe the effects of TS-011 on peri-infarct microcirculation.

20-HETE is known to be a potent vasoconstrictor (Harder et al., 1994). An inhibitor of 20-HETE synthesis or a 20-HETE antagonist reportedly attenuated the vasoconstrictor actions of 20-HETE in dissociated arteries (Yu et al., 2004). In this study, we focused on the effects of changes in the diameters of microvessels on the microvascular perfusion area. TS-011 significantly inhibited the reduction in the microvascular perfusion area after reperfusion. A previous report has confirmed that TS-011 at the same dose used in this study has no effect on blood pressure in rats (Omura et al., 2006). Therefore, this improvement of microvascular perfusion in peri-infarct region is unlikely to be caused by an increase in blood pressure. Because TS-011 has no effect on blood coagulation or fibrinolysis (data not shown), we hypothesized that TS-011 inhibited the vasoconstriction and/or vasospasms that follow cerebral ischaemia, thereby improving the peri-infarct microcirculation impaired by 20-HETE in a mouse transient MCAO model.

Whether the attenuation of peri-infarct microcirculation fluctuation induced by TS-011 can account for the reduction in the infarct volume observed in this model, however, remains uncertain. 20-HETE increases the production of oxidative stress (Guo et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2008). It also inhibits Na+, K+-ATPase activity (Nowicki et al., 1997) and activates the intracellular signalling pathway associated with apoptosis (Muthalif et al., 1998). In addition, arachidonic acid is metabolized to HETEs and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), which are potent vasodilators, through the action of cytochrome P450s (Harder et al., 1995). The inhibition of 20-HETE synthesis might up-regulate EETs, thereby exerting a protective effect against cerebral ischaemic injury (Zhang et al., 2007). Thus, the inhibition of 20-HETE synthesis might protect the brain from ischaemic insult by reducing oxidative stress, preventing the loss of Na+, K+-ATPase activity, inhibiting the apoptosis cascade activation, and/or up-regulating the production of EETs. Thus, the effect of TS-011 on all these possibilities, and not only the improvement of peri-infarct microcirculation, should be considered. Further study is needed to address the detailed mechanism of action of TS-011.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that TS-011 improved the impaired blood flow velocities of microvessels in the peri-infarct region and inhibited the reduction of the microvascular perfusion area after cerebral ischaemia. The improvement of peri-infarct microcirculation appears to be one of the mechanisms of action of TS-011. TS-011 might be a potentially beneficial agent for the treatment of ischaemic stroke.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant for Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology from Japan Science to J. N.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 20-HETE

20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- EETs

epoxyeicosatrienoic acids

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- SR101

sulforhodamine 101

- TPLSM

two-photon laser-scanning microscopy

- TS-011

N-(3-chloro-4-morpholin-4-yl) phenyl-N′-hydroxyimido formamide

Conflict of interest

T. M. and T. O. are employees of Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelt AA, Anjum N, Rajneesh KF, Kulesza P, Koehler RC. Estradiol augments peri-infarct cerebral vascular density in experimental stroke. Exp Neurol. 2007;206:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrup J, Siesjö BK, Symon L. Thresholds in cerebral ischemia – the ischemic penumbra. Stroke. 1981;12:723–725. doi: 10.1161/01.str.12.6.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayata C, Dunn AK, Gursoy-OZdemir Y, Huang Z, Boas DA, Moskowitz MA. Laser speckle flowmetry for the study of cerebrovascular physiology in normal and ischemic mouse cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:744–755. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000122745.72175.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardutzky J, Shen Q, Henninger N, Schwab S, Duong TQ, Fisher M. Characterizing tissue fate after transient cerebral ischemia of varying duration using quantitative diffusion and perfusion imaging. Stroke. 2007;38:1336–1344. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259636.26950.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Ou JS, Singh H, Falck JR, Narsimhaswamy D, Pritchard KA, et al. 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid causes endothelial dysfunction via eNOS uncoupling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1018–H1026. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01172.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolla MJ, Curry AB. Middle cerebral artery function after stroke: the threshold duration of reperfusion for myogenic activity. Stroke. 2002;33:2094–2099. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020712.84444.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Ruetzler CA, Hallenbeck JM. Temporal impairment of microcirculatory perfusion following focal cerebral ischemia in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Brain Res. 1997;749:200–208. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)01166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dorsten FA, Olàh L, Schwindt W, Grüne M, Uhlenküken U, Pillekamp F, et al. Dynamic changes of ADC, perfusion, and NMR relaxation parameters in transient focal ischemia of rat brain. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:97–104. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JH, Liu KF, Yoshida Y, Lian J, Chen S, del Zoppo GJ. Influx of leukocytes and platelets in an evolving brain infarct (Wistar rat) Am J Pathol. 1994a;144:188–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JH, Liu KF, Yoshida Y, Chen S, Lian J. Brain microvessels: factors altering their patency after the occlusion of a middle cerebral artery (Wistar rat) Am J Pathol. 1994b;145:728–740. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebremedhin D, Lange AR, Lowry TF, Taheri MR, Birks EK, Hudetz AG, et al. Production of 20-HETE and its role in autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Circ Res. 2000;87:60–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo AM, Arbab AS, Falck JR, Chen P, Edwards PA, Roman RJ, et al. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor through reactive oxygen species mediates 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-induced endothelial cell proliferation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:18–27. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.115360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenbeck JM, Dutka AJ. Background review and current concepts of reperfusion injury. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:1245–1254. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530110107027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder DR, Gebremedhin D, Narayanan J, Jefcoat C, Falck JR, Campbell WB, et al. Formation and action of a P-450 4A metabolite of arachidonic acid in cat cerebral microvessels. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H2098–H2107. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.5.H2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder DR, Campbell WB, Roman RJ. Role of cytochrome P-450 enzymes and metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of vascular tone. J Vasc Res. 1995;32:79–92. doi: 10.1159/000159080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F, Kleinfeld D. Chapter 10. In vivo measurements of blood flow and glial cell function with two-photon laser-scanning microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2008;444:231–254. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossmann KA. Pathophysiology and therapy of experimental stroke. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:1057–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9008-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe P, Oligo C, Domenga V, Tournier-Lasserve E, Joutel A. Impaired cerebral vasoreactivity in a transgenic mouse model of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy arteriopathy. Stroke. 2005;36:1053–1058. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000163080.82766.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassen NA. Cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in man. Physiol Rev. 1959;39:183–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1959.39.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmberg J, Putz C, Fürst M, Beck J, Baethmann A, Uhl E. Impact of the endothelin-A receptor antagonist BQ 610 on microcirculation in global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Brain Res. 2003;961:277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03974-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TN, He YY, Wu G, Khan M, Hsu CY. Effect of brain edema on infarct volume in a focal cerebral ischemia model in rats. Stroke. 1993;24:117–121. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay J, Mensah G, editors. The Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Part three: the burden: Global burden of stroke; pp. 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mies G, Ishimaru S, Xie Y, Seo K, Hossmann KA. Ischemic thresholds of cerebral protein synthesis and energy state following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:753–761. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata N, Seki T, Tanaka Y, Omura T, Taniguchi K, Doi M, et al. Beneficial effects of a new 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthesis inhibitor, TS-011 [N-(3-chloro-4-morpholin-4-yl) phenyl-N′-hydroxyimido formamide], on hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:77–85. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthalif MM, Benter IF, Karzoun N, Fatima S, Harper J, Uddin MR, et al. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid mediates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12701–12706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T. Living cell functions and morphology revealed by two-photon microscopy in intact neural and secretory organs. Mol Cells. 2008;26:113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Friedman B, Tsai PS, Lyden PD, Kleinfeld D. Targeted insult to subsurface cortical blood vessels using ultrashort laser pulses: three models of stroke. Nat Methods. 2006;3:99–108. doi: 10.1038/nmeth844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki S, Chen SL, Aizman O, Cheng XJ, Li D, Nowicki C, et al. 20-Hydroxyeicosa-tetraenoic acid (20 HETE) activates protein kinase C. Role in regulation of rat renal Na+,K+-ATPase. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1224–1230. doi: 10.1172/JCI119279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Copeland BR, Fitridge R, Koziol JA, del Zoppo GJ. Fibrin contributes to microvascular obstructions and parenchymal changes during early focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Stroke. 1994;25:1847–1853. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.9.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T, Tanaka Y, Miyata N, Koizumi C, Sakurai T, Fukasawa M, et al. Effect of a new inhibitor of the synthesis of 20-HETE on cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury. Stroke. 2006;37:1307–1313. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217398.37075.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel TR, Galbraith S, Graham DI, Hallak H, Doherty AM, McCulloch J. Endothelin receptor antagonist increases cerebral perfusion and reduces ischaemic damage in feline focal cerebral ischaemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:950–958. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1990;2:161–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renic M, Klaus JA, Omura T, Kawashima N, Onishi M, Miyata N, et al. Effect of 20-HETE inhibition on infarct volume and cerebral blood flow after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:629–639. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman RJ. P-450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of cardiovascular function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:131–185. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubart M. Two-photon microscopy of cells and tissue. Circ Res. 2004;95:1154–1166. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150593.30324.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer CB, Friedman B, Nishimura N, Schroeder LF, Tsai PS, Ebner FF, et al. Two-photon imaging of cortical surface microvessels reveals a robust redistribution in blood flow after vascular occlusion. PloS Biol. 2006;4:e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatz M, Yasuma Y, Strasser A, McCarron RM. Cerebral postischemic hypoperfusion is mediated by ETA receptors. Brain Res. 1996;726:242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovic B, Hutchinson E, Yakovleva V, Schram V, Russell JT, Belluscio L, et al. Functional reactivity of cerebral capillaries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:961–972. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu H, Tsukada H, Kakiuchi T, Tatsumi M, Umemura K. Changes in local cerebral blood flow in photochemically induced thrombotic occlusion model in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:375–379. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Omura T, Fukasawa M, Horiuchi N, Miyata N, Minagawa T, et al. Continuous inhibition of 20-HETE synthesis by TS-011 improves neurological and functional outcomes after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurosci Res. 2007;59:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theer P, Hasan MT, Denk W. Two-photon imaging to a depth of 1000 µm in living brains by use of a Ti:Al2O3 regenerative amplifier. Opt Lett. 2003;15:1022–1024. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.001022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yushmanov VE, Liachenko SM, Tang P, Hamilton RL, Xu Y. Late reversal of cerebral perfusion and water diffusion after transient focal ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:253–261. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Okada Y, Ibayashi S. Therapeutic time window for YAG laser-induced reperfusion of thrombotic stroke in hypertensive rats. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1005–1008. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200206120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Cambj-Sapunar L, Kehl F, Maier KG, Takeuchi K, Miyata N, et al. Effects of a 20-HETE antagonist and agonists on cerebral vascular tone. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;486:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Murphy TH. Imaging the impact of cortical microcirculation on synaptic structure and sensory-evoked hemodynamic responses in vivo. PloS Biol. 2007;5:e119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Koerner IP, Noppens R, Grafe M, Tsai HJ, Morisseau C, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase: a novel therapeutic target in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1931–1940. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Zoppo GJ, Mabuchi T. Cerebral microvessel responses to focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:879–894. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000078322.96027.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Zoppo GJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Mori E, Copeland BR, Chang CM. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes occlude capillaries following middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion in baboons. Stroke. 1991;22:1276–1283. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.10.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]