Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Halofantrine can cause a prolongation of the cardiac QT interval, leading to serious ventricular arrhythmias. Hyperlipidaemia elevates plasma concentration of halofantrine and may influence its tissue uptake. The present study examined the effect of experimental hyperlipidaemia on QT interval prolongation induced by halofantrine in rats.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats (induced with poloxamer 407) were given 4 doses of halofantrine (i.v., 4–40 mg·kg−1·d−1) or vehicle every 12 h. Under brief anaesthesia, ECGs were recorded before administration of the vehicle or drug and 12 h after the first and last doses. Blood samples were taken at the same time after the first and last dose of halofantrine. Hearts were also collected 12 h after the last dose. Plasma and heart samples were assayed for drug and desbutylhalofantrine using a stereospecific method.

KEY RESULTS

In the vehicle group, hyperlipidaemia by itself did not affect the ECG. Compared to baseline, QT intervals were significantly higher in both normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats after halofantrine. In hyperlipidaemic rats, plasma but not heart concentrations of the halofantrine enantiomers were significantly higher compared to those in normolipidaemic rats. Despite the lack of difference in the concentrations of halofantrine in heart, QT intervals were significantly higher in hyperlipidaemic compared to those in normolipidaemic rats.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The unbound fraction of halofantrine appeared to be the controlling factor for drug uptake by the heart. Our data suggested a greater vulnerability to halofantrine-induced QT interval prolongation in the hyperlipidaemic state.

Keywords: halofantrine, hyperlipidaemia, lipoproteins, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics

Introduction

Hyperlipidaemia is a pathological state characterized by increases in serum lipoproteins, primarily of the low and very low density categories. These elevated levels of low density lipoproteins (LDL) can lead to atherosclerosis and an increased risk of serious cardiovascular diseases, including stroke and myocardial infarction (Austin, 1999; Genest et al., 2003). Hyperlipidaemia has a number of causes including heredity (Hegele, 2009), lifestyle (Kris-Etherton et al., 1988; Lichtenstein et al., 1998; Rakic et al., 1998), metabolic disorders (Kreisberg, 1998; Wanner and Quaschning, 2001; Wanner and Krane, 2002; Panza et al., 2006; Duntas and Wartofsky, 2007; Adibhatla and Hatcher, 2008) and drug therapy (e.g. immunosuppressant therapy) (Mantel-Teeuwisse et al., 2001).

Hyperlipidaemia has the ability to change the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of lipoprotein-bound drugs (Wasan and Conklin, 1997; Eliot and Jamali, 1999; Eliot et al., 1999; Shayeganpour et al., 2005; Aliabadi et al., 2006; Brocks et al., 2006; Wasan et al., 2008; Hamdy and Brocks, 2009), one example of which is the antimalarial drug (+/−)-halofantrine (Patel et al., 2009). The pharmacokinetics of halofantrine are stereoselective, in that the (+)-enantiomer attains higher plasma concentrations than the (−)-enantiomer (Gimenez et al., 1994; Brocks and Toni, 1999; Abernethy et al., 2001). After oral doses, the absorption of halofantrine is erratic. This is of potential concern because the drug can cause life threatening ventricular dysrhythmias, such as Torsades de pointes, in susceptible patients. If bioavailability is higher in some patients, they may be more at risk of arrhythmias (Monlun et al., 1995; Abernethy et al., 2001). A maximal QT interval prolongation was observed at plasma concentrations of ∼1400 ng·mL−1 halofantrine (Nosten et al., 1993; Karbwang and Na Bangchang, 1994), near that of maximal plasma concentrations (sum of enantiomers) measured in malaria patients after 3 doses of 500 mg given orally every 6 h (1200 ng·mL−1) (Karbwang et al., 1991). Although QT prolongation was observed after halofantrine treatment, ventricular arrhythmias were reported only in the patients with underlying cardiac disease, with co-administration of other QT prolonging drugs, or improper dosing of halofantrine (Bouchaud et al., 2009). The cardiac toxicity of halofantrine is attributed to its concentration-dependent prolongation of QT interval mediated via inhibition of potassium channels, such as the KV11.1 – cardiac IKR potassium channel (Tie et al., 2000; Batey and Coker, 2002; channel nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2009). Although both enantiomers are equipotent in their antimalarial activities, in vitro (Basco et al., 1992) (+)-halofantrine exhibits more potent prolongation of QT interval compared to its antipode (Wesche et al., 2000).

Halofantrine is relatively slowly but extensively metabolized in rats and humans (Karbwang and Na Bangchang, 1994; Gharavi et al., 2007). (+/−)-Desbutylhalofantrine (DHF) is the major circulating active metabolite of halofantrine, formed primarily by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms (Gharavi et al., 2007). DHF is equipotent to halofantrine in its antimalarial effect (Basco et al., 1994), and like halofantrine can prolong the QT interval; there is some debate, however, over whether the metabolite is less, equal or more active than the parent drug (Wesche et al., 2000; McIntosh et al., 2003).

In preclinical species, elevation of plasma lipoproteins induces higher halofantrine plasma concentrations, due to lower values of clearance, volume of distribution and unbound fraction (Humberstone et al., 1998b; Brocks and Wasan, 2002). For most drugs, it is assumed that only unbound drug in plasma can traverse tissue cell membranes and elicit pharmacological response, when the target receptors lie within tissue cells. However, in hyperlipidaemia, tissue accumulation of drug could be enhanced due to selective uptake of the drug-lipoprotein complex by lipoprotein receptors present in various tissues (Takahashi et al., 2003; Chung and Wasan, 2004). For instance, amiodarone uptake in heart, a tissue replete with very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) receptors, was increased more than expected in hyperlipidaemia, compared to normolipidaemia, even though plasma unbound fraction was lower (Shayeganpour et al., 2008).

Given the potential seriousness of QT prolongation in halofantrine use, it is particularly important to identify factors which might influence its ability to prolong the QT interval. Thus, far there has been one attempt made to study the influence of hyperlipidaemia on halofantrine cardiotoxicity (McIntosh et al., 2004). It was reported that while halofantrine caused prolongation of the QT interval in normolipidaemic rabbits, very little increase occurred in hyperlipidaemic animals. The study may not have been conclusive, however, due to the experimental design utilized. For example, the ECGs were obtained under conditions of relatively long-term anaesthesia (at least 75 min, not including surgery) and mechanical ventilation, both of which could have influenced the QT interval (Owczuk et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010). Although stereoselectivity in cardiac effects were known (Wesche et al., 2000), a non-stereospecific assay was used to measure halofantrine. More importantly, drug and metabolite concentrations in the heart, the target organ for the toxicity, were not assessed.

In the present report, we describe the influence of an experimental rat model of hyperlipidaemia on the plasma and heart concentrations of halofantrine and DHF enantiomers after repeated doses of the racemate. The dosage regimen was intended to approximate that given to patients, with 4 doses given sequentially over a 36-h period. ECG readings assessed without knowledge of treatments, were used to measure the resultant QT intervals during the post-distributive phase of the plasma concentration – time profile.

Methods

Experimental animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the University of Alberta Health Sciences Animal Policy and Welfare Committee. A total of 42 male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, CRC, QC, Canada) with body weight ranging from 250–350 g were used in this study. All rats were housed in temperature-controlled room with a 12-h dark/light cycle. The animals were fed a standard rodent chow containing 4.5% fat (Lab Diet 5001, PMI nutrition LLC, Brentwood, MO, USA). Free access to food and water was permitted throughout the experiments.

Rats were either rendered normolipidaemic or hyperlipidaemic through intraperitoneal injection of saline or 1 g·kg−1 poloxamer 407 (P407) (0.13 g mL−1 solution in normal saline), respectively, given under light isoflurane anaesthesia. A total of 2 doses of P407 or saline were administered to the rats. The next day after the first dose of P407 or saline, Silastic (Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) cannulas were implanted into the right jugular veins under isoflurane/O2 anaesthesia. After surgery, the implanted cannulas were filled with 100 U·mL−1 heparin in 0.9% saline and rats were transferred to regular holding cages. The next morning, rats were transferred to plastic metabolic cages for dosing and blood sample collection.

To provide for a wide range of halofantrine concentrations, normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats received halofantrine HCl in doses of 4, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mg·kg−1·d−1. This dose range encompassed those given clinically, as well as those known to cause QT prolongation in humans (Nosten et al., 1993). The main comparison dose group comprised rats given 20 mg·kg−1·d−1, in which 8 rats were present in each of the normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic groups. To gain some insight into the relationships between dose given and the plasma and tissue concentration and the ECG recorded, other smaller groups of animals received doses of 4, 10, 30 or 40 mg·kg−1·d−1 (two to three rats per dose). Drug-free vehicle normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic treated animals were included (n= 4 each).

Halofantrine dosing, ECG measurements and sample collection

A dosing solution of (+/−)-halofantrine HCl (5 mg·mL−1) was prepared in N, N-dimethylacetamide: polyethylene glycol 400: 5% dextrose in water: acetic acid (16:24:160:1) (Brocks and Wasan, 2002). At approximately 36 h after first i.p. dose of saline or P407, a total of 4 separate doses of halofantrine HCl or vehicle were administered to normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats over 2 d with 12 h intervals between each dose. The drug solution was administered slowly over a time period of 60 s through the implanted right jugular vein cannula immediately followed by the administration of 0.5 mL of saline for injection to flush the drug solution remaining in the cannula. Between doses, each cannula was filled with heparin 1000 U·mL−1: polyethylene glycol 400: cefazolin 100 mg·mL−1 of sterile water for injection (25:55:20). Based on the pharmacokinetic profile and the time of duration of P407 effect (Wout et al., 1992; Li et al., 1996), hyperlipidaemia was maintained over the course of experiment by i.p. injection of a second dose of P407 just after the second dose of halofantrine HCl. For normolipidaemic rats, equivalent volumes of saline were injected in place of P407 solution.

To obtain the ECG traces, animals were lightly anesthetized under isoflurane anaesthesia administered by an anaesthetic machine. Traces were recorded under light anaesthesia to prevent environmental disruptions associated with blood sample collection from influencing the ECG readings. Immediately upon loss of consciousness, the rats had three stainless steel needle electrodes inserted subcutaneously in a triangular configuration over the thorax (aVF, aVL and aVR). Twelve-second ECG recordings were then recorded. The total elapsed time from placement of the rat in the anaesthetic chamber to recording of the ECG varied from 3 to no more than 5 min.

Recordings were made using a P55 general purpose AC preamplifier and the PolyVIEW data acquisition and analysis system (Grass Instrument Division, Astro-Medical, Inc, West Warwick, RI, USA). The ECG recordings were taken at baseline conditions (before first dose of intraperitoneal injection of saline or P407 and before right jugular vein cannulation) and 12 h after the first and fourth doses of halofantrine. To remove assessor bias in the ECG recording, a random code was assigned to the recorded ECG strips, thus assuring that the assessor was unaware of the type of treatment or time of ECG recordings for PR (measured from the start of P wave to appearance of the R wave), RR and QT (measured from the inflection of the Q wave to the end of the T wave) interval measurements. The QT intervals were also normalized to the heart rate (QTc) using the Fridericia [QTc = QT(s)·RR(s)−1/3] formula (Hamdy and Brocks, 2009). From each 12-s strip, five measures of PR, RR and QT interval from separate cardiac cycles were made to arrive a mean value for that time point in that rat.

In order to correlate the ECG measurements with plasma concentration of halofantrine and DHF enantiomers, blood samples were collected into heparinized tubes immediately following the ECG recordings at 12 h after the first dose (∼0.5 mL blood through tail vein) and the last dose (through cardiac puncture) of halofantrine. All blood samples were centrifuged at 2500×g for 15 min to separate plasma from the blood cells. Blood collected at the end of the study was also used to measure the total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) in the plasma. After cardiac puncture, hearts were harvested and blotted on the tissue paper to remove excess blood. All plasma and tissue samples were stored at −30°C until assayed for drug and metabolite.

Assay

Analysis of halofantrine and DHF enantiomers in biological samples was performed using validated stereospecific high-performance liquid chromatography assays (Brocks et al., 1995; Brocks, 2001; Patel et al., 2009). To quantify the concentrations of halofantrine and DHF enantiomers in plasma and homogenized heart tissues, standard curves composed of blank plasma and heart tissue homogenates, with known amounts of added halofantrine or DHF were used. For assay in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats, blank plasma and tissues from similar normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic animals, respectively, had analyte added similarly and were used for standard curves. The TC and TG plasma concentrations were measured using enzymatic assay kits according to the manufacturer's (Diagnostic Chemicals Limited, Charlottetown, PE, Canada) guidelines.

Data and statistical analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SD. The accumulation factors for halofantrine enantiomers in plasma were determined as the ratios of the 12-h post-dose concentrations of the last to the first dose. The unbound plasma concentration of halofantrine enantiomers was calculated by multiplying the total measured plasma enantiomer concentrations by the previously reported unbound fractions of 0.00064 and 0.00007 for (+) and 0.00062 and 0.000077 for (−)-halofantrine enantiomers in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats respectively (Brocks and Wasan, 2002). The comparison of means were accomplished using Student's unpaired or paired t-tests as appropriate. For multiple comparisons of ECG, the Bonferroni correction was applied. Linear regression was used to characterize the relationships between various measures, using the correlation coefficient (r2) as a measure of the strength of relationship. In all figures, absence of regression line denotes non-significant correlation between tested parameters. The level of significance in all statistical testing was set at α= 0.05.

Materials

(+/−)-Halofantrine HCl and (+/−)-DHF HCl were gifts from SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals (Worthing, UK). Poloxamer 407 was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Heparin sodium injection (Leo Pharma, Thornhill, ON, Canada) and cefazolin (Novopharm, Toronto, ON, Canada) were purchased from the University of Alberta Hospitals. Isoflurane USP was purchased from Halocarbon Products Corporation (River Edge, NJ, USA). Total serum cholesterol and triglyceride assay kits were purchased from Diagnostic Chemicals Limited (Charlottetown, PE, Canada).

Results

Lipid concentrations

As expected (Wout et al., 1992), significant rises in the plasma TC and TG were noted in P407 treated rats. At the end of the study, increases in TC and TG were 12- and 29-fold, respectively, in hyperlipidaemic compared to normolipidaemic rats (Table 1).

Table 1.

The mean ± SD of ECG parameters, plasma and heart concentration of halofantrine (HF) and desbutylhalofantrine (DHF) enantiomers and plasma cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) in vehicle control and HF-treated normolipidaemic (NL) and hyperlipidaemic (HL) rats before (baseline), or 12 h after the first and last doses

| Vehicle control | 20 mg·kg−1·d−1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL | HL | NL | HL | ||

| ECG parameters (ms) | |||||

| QT | Baseline | 70.5 ± 1.81 | 72.9 ± 2.06 | 73.1 ± 4.94 | 74.6 ± 7.68 |

| First dose | 74.2 ± 2.23 | 75.9 ± 2.60 | 72.4 ± 4.86 | 79.3 ± 8.24 | |

| Last dose | 68.9 ± 2.66 | 71.9 ± 4.83 | 80.2 ± 6.05*† | 90.2 ± 7.19*†‡ | |

| QTc | Baseline | 132 ± 5.26 | 137 ± 5.06 | 137 ± 8.99 | 140 ± 12.9 |

| First dose | 142 ± 5.77 | 144 ± 3.23 | 137 ± 10.3 | 149 ± 13.9 | |

| Last dose | 130 ± 3.29 | 134 ± 10.9 | 148 ± 10.6*† | 165 ± 13.6*†‡ | |

| RR | Baseline | 152 ± 6.57 | 150 ± 5.55 | 153 ± 8.04 | 151 ± 6.25 |

| First dose | 144 ± 8.87 | 146 ± 5.21 | 149 ± 14.4 | 151 ± 11.2 | |

| Last dose | 150 ± 8.79 | 155 ± 8.04 | 161 ± 7.56* | 163 ± 8.62* | |

| PR | Baseline | 49.6 ± 1.01 | 49.2 ± 2.79 | 51.0 ± 2.83 | 47.9 ± 2.41 |

| First dose | 47.5 ± 1.00 | 50.1 ± 2.20 | 52.1 ± 3.65 | 50.0 ± 3.42 | |

| Last dose | 48.9 ± 0.89 | 49.5 ± 2.78 | 52.6 ± 4.86 | 50.6 ± 2.53 | |

| HF (µg·mL−1 or g−1) | |||||

| (+) Plasma | First dose | 0.83 ± 0.52 | 6.24 ± 0.93‡ | ||

| (+) Plasma | Last dose | 1.04 ± 0.31 | 14.7 ± 4.21‡ | ||

| (+) Heart | Last dose | 8.85 ± 2.47 | 8.56 ± 1.37 | ||

| (−) Plasma | First dose | 0.53 ± 0.49 | 2.91 ± 0.75‡ | ||

| (−) Plasma | Last dose | 0.30 ± 0.086 | 4.38 ± 1.07‡ | ||

| (−) Heart | Last dose | 2.27 ± 0.56 | 2.51 ± 0.43 | ||

| DHF (µg·mL−1 or g−1) | |||||

| (+) Plasma | Last dose | 0.44 ± 0.10 | 0.59 ± 0.18 | ||

| (+) Heart | Last dose | 5.95 ± 1.85 | 4.17 ± 1.60 | ||

| (−) Plasma | Last dose | 0.067 ± 0.020 | 0.21 ± 0.056‡ | ||

| (−) Heart | Last dose | 2.09 ± 0.73 | 1.85 ± 0.64 | ||

| Lipid levels (mmol·L−1) | |||||

| TC | 2.83 ± 0.35 | 35.8 ± 8.69‡ | |||

| TG | 1.70 ± 0.40 | 58.7 ± 15.4‡ | |||

Blank cells represent values either not measured or calculated. For multiple comparisons of ECG parameters, Bonferroni correction was applied with P= 0.0167.

Significantly different from baseline.

Significantly different from vehicle control.

Significantly different from NL group.

Drug and metabolite concentrations

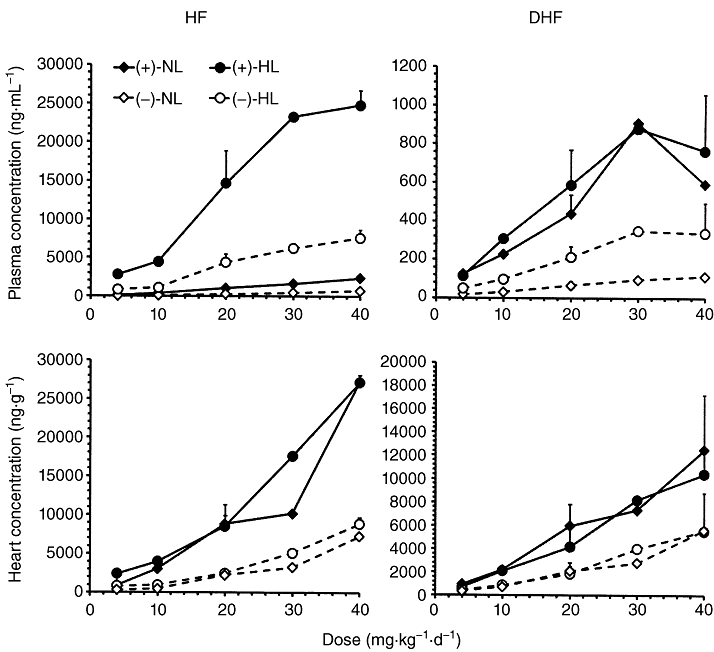

In all animals, the enantiomers of halofantrine and DHF were measurable in plasma and heart at the end of the study (Figure 1). With increases in dose, there were increases in the plasma and heart concentrations although at the 40 mg·kg−1·d−1 dose level there seemed to be a plateau in the relationships for halofantrine and DHF enantiomers in plasma. In contrast, in heart no such plateau was noted; rather a greater than proportional increase in heart tissues appeared as the doses increased (Figure 1). Because the numbers of animals in dose groups other than 20 mg·kg−1·d−1 were small, it was not possible to make definite conclusions regarding linearity.

Figure 1.

The mean ± SD concentrations of halofantrine (HF) and desbutylhalofantrine (DHF) enantiomers in normolipidaemic (NL) and hyperlipidaemic (HL) rats 12 h after the last (+/−)-HF doses of 4, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mg·kg−1·d−1.

In the 20 mg·kg−1·d−1 dose group, the accumulation factors for mean plasma concentration of (+)-halofantrine in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats, respectively, were 1.74 ± 1.10 and 2.43 ± 0.94 between the first and last doses. In contrast, the corresponding accumulation factors for (−)-halofantrine were apparently less (1.12 ± 0.78 and 1.62 ± 0.69 in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic respectively). In other dose groups, the accumulation factors for mean plasma concentration of (+)-halofantrine in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats, respectively, were 1.35 and 1.85, 1.94 and 1.77, 1.88 and 2.73, and 2.22 and 2.77 for 4, 10, 30 and 40 mg·kg−1·d−1. The corresponding accumulation factors for mean plasma concentrations of (−)-halofantrine were 1.45 and 1.27, 1.60 and 1.33, 1.72 and 1.91, and 1.56 and 1.98. Hence, there seemed to be a trend towards increasing accumulation as the dose increased.

The (+)- and (−)-halofantrine enantiomers were strongly correlated (r2 ranging from 0.90 to 0.98) for both normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats within plasma and heart. The plasma and heart enantiomer concentrations of DHF were consistently lower than halofantrine in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats (Figure 1). Significant positive correlations were seen between DHF and halofantrine enantiomer concentrations in both normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats (Figure 2). In normolipidaemic rats these correlations were stronger for (−)-halofantrine than (+)-halofantrine in both plasma (r2= 0.75 vs. 0.32) and heart (r2= 0.91 vs. 0.70), possibly due to the more rapid metabolism of the (−)-enantiomer of halofantrine to DHF (Brocks and Toni, 1999; Gharavi et al., 2007). However, in hyperlipidaemic rats there were no such differences noted between enantiomers either in plasma or heart (Figure 2). The slopes in the DHF versus halofantrine relationships for both the (+)- and (−)-enantiomers in plasma were much higher in the normolipidaemic than the hyperlipidaemic rats (Figure 2, upper panels). In comparison, heart uptake of DHF enantiomers increased in a similar manner to increases in halofantrine in both the hyperlipidaemic and normolipidaemic rats (Figure 2, lower panels). The ratios of DHF: halofantrine were higher in plasma of the normolipidaemic than the hyperlipidaemic rats. Specifically, the range of DHF to halofantrine mean plasma ratios in the various dose groups for (+) enantiomer were 8 to 18-fold higher, and for (−) enantiomer 3 to 4.5-fold higher, in normolipidaemic than hyperlipidaemic rats. In heart, these relative ratios were closer to unity with the corresponding mean ratios for (+) and (−)-halofantrine being 1.2 to 3.4-fold, and 1.1 to 1.9-fold higher, respectively, in normolipidaemic than hyperlipidaemic rats.

Figure 2.

The correlation between plasma and heart concentration of halofantrine (HF) enantiomers with corresponding desbutylhalofantrine (DHF) enantiomers in normolipidaemic (NL) and hyperlipidaemic (HL) rats following administration of 4, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mg·kg−1·d−1.

The concentrations of both halofantrine enantiomers were significantly higher in plasma of hyperlipidaemic than normolipidaemic rats after 20 mg·kg−1·d−1 doses (Figure 1 and Table 1). For the metabolite (−)- but not (+)-DHF was significantly higher in hyperlipidaemic compared to normolipidaemic plasma (Figure 1 and Table 1). In heart, however, concentrations of halofantrine and DHF enantiomers were similar in both normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats (Figure 1 and Table 1).

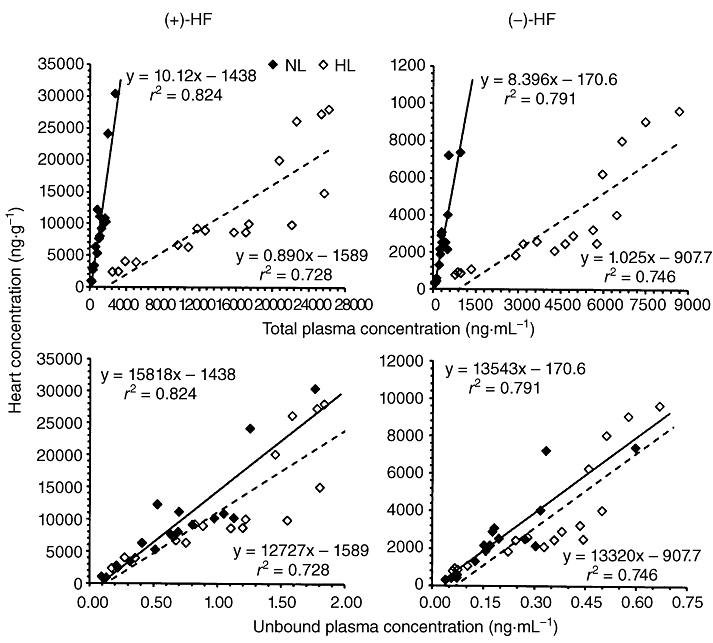

Strong positive linear relationships were noted upon comparing heart to total and unbound plasma concentration of halofantrine enantiomers in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats (Figure 3). Tenfold higher slopes were noted between total plasma versus heart concentration of halofantrine enantiomers in normolipidaemic compared to hyperlipidaemic rats (Figure 3, upper panels). In viewing the estimated unbound plasma versus heart concentrations; however, this difference in slopes was essentially obliterated (Figure 3, lower panels).

Figure 3.

The correlation between heart and total or unbound plasma concentration of halofantrine (HF) enantiomers in normolipidaemic (NL) and hyperlipidaemic (HL) rats following administration of 4, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mg·kg−1·d−1.

Effects of vehicle and hyperlipidaemia on the rat ECG

The halofantrine dosing vehicle had no significant effect on the ECG (Table 1). Hyperlipidaemia by itself had no significant effect on the rat ECG (Table 1).

Electrocardiographic effects of halofantrine

In the 20 mg·kg−1·d−1 dose group, the PR intervals were not significantly affected by repeated doses of halofantrine (Table 1). The QT intervals, however, were significantly longer than baseline in both normolipidaemic (+9.8 ± 2.3%) and hyperlipidaemic rats (+21.4 ± 11.2%) at the end of the study. The QTc were similarly affected (+7.89 ± 1.83% for normolipidaemic and +18.4 ± 11.8% for hyperlipidaemic). Furthermore, halofantrine caused the QT and QTc intervals in hyperlipidaemic rats to be significantly longer than in the normolipidaemic rats (Table 1). By taking the sum of the enantiomers and relating those concentrations to QT interval, the strength of the correlations seemed to be more in line with those of the (+)-enantiomer than the (−)-enantiomer in both plasma and heart (Table 2). At the end of the study, normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats displayed a modest but significant decrease in the heart rate (4.8–7.3% decrease) (Table 1).

Table 2.

The regression coefficients (r2) for the relationships between QT interval and corresponding plasma and heart concentrations when enantiomers were examined separately, or together in the form of halofantrine (HF) with or without desbutylhalofantrine (DHF)

| Plasma | Heart | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (+) | (−) | (+) + (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) + (−) | |

| Normolipidaemia | ||||||

| HF | 0.499 | 0.518 | 0.510 | 0.384 | 0.316 | 0.373 |

| HF + DHF | 0.413 | 0.504 | 0.438 | 0.359 | 0.305 | 0.347 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | ||||||

| HF | 0.187 | 0.287 | 0.210 | 0.303 | 0.373 | 0.322 |

| HF + DHF | 0.182 | 0.276 | 0.204 | 0.243 | 0.287 | 0.256 |

As plasma concentration of halofantrine enantiomers rose, there was a general linear increase in the QT interval in both normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats (Figure 4, upper panels). The addition of DHF and halofantrine plasma molar concentrations yielded essentially the same strength of relationship with QT interval as noted with halofantrine alone in both normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats (Table 2). In general, the relationships between heart halofantrine enantiomer concentrations and QT interval mirrored those seen in plasma (Figure 4, lower panels). It was observed that the slopes of heart enantiomer concentration versus QT interval were very similar between normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats. This was unlike the situation for plasma, where an 11-fold difference was noted for the (−)-enantiomer (Figure 4, upper panels). The sum of DHF and halofantrine heart molar concentrations versus QT interval resulted in numerically lower r2 values in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats for each enantiomer compared to the respective halofantrine enantiomer versus QT interval relationships (Table 2).

Figure 4.

The correlation between QT intervals and plasma or heart concentration of halofantrine enantiomers in normolipidaemic (NL) and hyperlipidaemic (HL) rats given 4, 10, 20, 30 and 40 mg·kg−1·d−1.

Discussion and conclusions

The hyperlipidaemic state can alter the pharmacokinetic properties of several lipoprotein-bound drugs including halofantrine, cyclosporin A, amiodarone, and amphotericin B (Brocks et al., 2006; Brocks and Wasan, 2002; Wasan et al., 1998; Eliot et al., 1999; Shayeganpour et al., 2005; Fukushima et al., 2009; Sugioka et al., 2009). The hyperlipidaemia-induced changes in the pharmacokinetics of these drugs can also potentially alter their pharmacodynamic properties. For instance, repeated dosing of amiodarone to hyperlipidaemic rats has resulted into higher heart uptake of amiodarone which in turn was significantly related to QT interval prolongation (Hamdy and Brocks, 2009). In another study, greater nifedipine-related reduction in mean arterial pressure was noted despite a decrease in unbound plasma concentrations in hyperlipidaemia (Eliot and Jamali, 1999). Similarly, both cyclosporin A (Aliabadi et al., 2006) and amphotericin B (Wasan and Conklin, 1997), each of which is bound to lipoproteins, demonstrated enhanced nephrotoxicities in hyperlipidaemia. An increase in the IC50 of halofantrine was observed when post-prandial serum was incubated with Plasmodium falciparum cultures in vitro (Humberstone et al., 1998a).

According to the Fredrickson-Levy-Lees classification, there are six categories of lipoprotein disorders which are commonly used as phenotypic descriptors of hyperlipidaemia (Beaumont et al., 1970). Depending on the type of disorder, animal models such as obese Zucker rats, genetically modified knockout mice (e.g. lipoprotein receptor or apolipoprotein E knockout mice) and chronic cholesterol fed laboratory animals are used (Russell and Proctor, 2006). In the present study, the P407 rat model, most closely resembling type IV hyperlipidaemia in humans, was used (Wout et al., 1992). The hyperlipidaemic state induced by P407 is acute (as is the case in our study), extreme and reversible in nature, but can be used as a chronic atherogenic model (Palmer et al., 1998) by administering repeated i.p. injections of the agent every few days.

In hyperlipidaemia, increased lipoprotein concentrations cause higher plasma concentrations of (+/−)-halofantrine and its enantiomers, compared to normolipidaemia (Figure 1) (Milton et al., 1989; Humberstone et al., 1998b; Brocks and Wasan, 2002). In hyperlipidaemic plasma, elevated levels of halofantrine enantiomers can be attributed to their increased lipoprotein binding thereby reducing the unbound fraction (Brocks and Wasan, 2002), and decreased metabolism by reduction in hepatic CYP3A and 2C11 (Brocks et al., 1995; Brocks, 2001; Shayeganpour et al., 2008; Patel et al., 2009). Theoretically, for a low hepatic extraction ratio drug with high volume of distribution such as halofantrine, a decrease in its plasma unbound concentration should result in proportional decreases in its clearance and its volume of distribution. The net effect would be no change in the unbound plasma or total tissue concentration. This expectation is in line with the similarity in total heart uptake of halofantrine enantiomers between normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats after repeated dosing (Figure 1 and Table 1). In addition, when the measured total (bound + unbound) plasma concentrations of halofantrine enantiomers were converted to estimated unbound concentrations based on the unbound concentrations observed previously (Brocks and Wasan, 2002) in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats, the slopes of the lines for normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats became virtually parallel. This suggests that for halofantrine, it is the unbound concentrations in plasma which determines the drug's ability to leave plasma and enter cells, including not only cardiomyocytes, but also the malaria parasite (Humberstone et al., 1998a).

This is unlike the case of the anti-arrhythmic drug amiodarone in the same animal model of hyperlipidaemia (Hamdy and Brocks, 2009). Like halofantrine, large differences were noted in the regression slopes of the drug in plasma versus heart uptake in the normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic animals (similar to Figure 3, upper panel). When the same procedure (Figure 3) was applied to ascertain the unbound concentrations of amiodarone versus heart uptake; however, the slopes remained very different between the unbound plasma versus heart concentrations in the normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats. It was suggested that amiodarone heart uptake was enhanced by its ability to enter into VLDL particles. Heart possesses a high density of VLDL receptors, which is able to efficiently sequester intermediate density lipoproteins derived from VLDL (Takahashi et al., 2003; Chung and Wasan, 2004). Therefore, it was proposed that VLDL receptor-mediated uptake of VLDL-associated amiodarone might have caused an increased cardiac accumulation in the hyperlipidaemic state (Hamdy and Brocks, 2009).

Even though amiodarone and halofantrine share an increased uptake in VLDL-containing fractions in hyperlipidaemic plasma, their relative uptakes into the various lipoprotein-containing fractions of separated plasma differ (Table 3)(Brocks et al., 1995; Brocks, 2001; Shayeganpour et al., 2007; Patel et al., 2009). In reviewing earlier studies, it was noted that the hyperlipidaemia: normolipidaelia ratio of amiodarone in TG-rich fractions was ∼10.6-fold, compared to only 3.0- and 4.1-fold for (+)- and (−)-halofantrine respectively (Table 3). Furthermore, halofantrine enantiomers tended to be more associated with lipoprotein-deficient and LDL fractions in hyperlipidaemic plasma. The hyperlipidaemic state also had a greater effect on unbound fraction of amiodarone, compared to its effect on the halofantrine enantiomers (Table 3). It is clear that amiodarone has a higher affinity for VLDL than does halofantrine in this hyperlipidaemic rat model. Therefore, in contrast to amiodarone, the lack of change in heart uptake of halofantrine enantiomers could be due to their lower affinity towards VLDL particles in hyperlipidaemic plasma.

Table 3.

Comparison of ratios of drug residence within rat plasma lipoprotein fractions, and change in plasma unbound fraction (fu), in hyperlipidaemic (HL) rats given poloxamer 407(P407), relative to normolipidaemic (NL) plasma, based on previous reports (Patel et al., 2009; Shayeganpour et al., 2007)

| Halofantrine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipoprotein fraction | Amiodarone | (+) | (−) |

| Lipoprotein deficient | 0.035 | 0.393 | 0.298 |

| HDL | 0.021 | ↓ | ↓ |

| LDL | 0.750 | 0.966 | 1.07 |

| Triglyceride rich | 10.9 | 3.04 | 4.09 |

| Change in fu | −96% | −89% | −88% |

HDL and LDL denote high- and low-density lipoprotein fractions, respectively; ↓ Denotes decrease, drug detected in NL but not HL (ratio not calculable); Triglyceride-rich refers mostly to very low density lipoprotein in the P407 model.

The prolongation of the QT interval by halofantrine is a major concern in the clinical use of the drug (White, 2007; Bouchaud et al., 2009). In line with human data (Abernethy et al., 2001), both halofantrine enantiomers showed concentration-dependent increases in the prolongation of QT intervals in normolipidaemic rats. Similar relationships were noted with hyperlipidaemic rats for the (−)-halofantrine but not (+)-halofantrine (Figure 4, upper panels). Previously, Wesche et al. (2000) showed that (+)-halofantrine was more potent compared to (−)-halofantrine in its prolongation of QT intervals in cat isolated cardiomyocytes. It was of interest that, in taking the sum of the two enantiomers and correlating the values to QT interval, the regression coefficients generally were more in line with the (+)-enantiomer than the (−)-enantiomer (Table 2). We cannot conclusively differentiate between the relative potency of halofantrine enantiomers on QT interval prolongation, because racemic halofantrine was administered rather than individual enantiomers and because concentrations of the enantiomers were strongly correlated in plasma and heart.

There have been some conflicting views expressed regarding the effect of DHF on QT interval prolongation (Wesche et al., 2000; Mbai et al., 2002; McIntosh et al., 2003). Wesche et al. (2000) had reported that halofantrine was considerably more potent at extending the QT interval in isolated perfused cat hearts than DHF (Wesche et al., 2000). McIntosh et al. later examined the effect of DHF on the rabbit QT interval (McIntosh et al., 2003). They found that not only could DHF significantly prolong the QT interval, but also that it was probably equipotent to halofantrine. Although halofantrine was not given to animals directly, the claim was based on the findings of Lightbown et al. who gave halofantrine but not metabolite, using essentially the same study design (Lightbown et al., 2001). Based on a smaller cumulative dose, the QT prolonging activity of DHF indeed seemed to be similar to halofantrine. Some reflection is needed here, however. For example, in rats the areas under the curve of DHF enantiomers in heart are considerably higher after administration of preformed metabolite, compared to that of equivalent doses of halofantrine (Brocks, 2002). Furthermore, prolonged anaesthesia with mechanical ventilation could have modified the intrinsic QT prolonging effects of drug or metabolite (Owczuk et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010). The ECG measures were also recorded shortly after dosing of the rabbits with either halofantrine or DHF, which could have potentially obscured some differences between the drug and metabolite if the pseudo-equilibrium between plasma and tissues had not been fully realized. The possibility of interspecies differences between rabbit and cat in response to halofantrine and DHF was offered as an explanation for the relatively greater effect of DHF in the rabbit (McIntosh et al., 2003).

Although we did not administer preformed DHF to our rats, we did measure considerable DHF concentrations in the rat heart after repeated doses of halofantrine. When the molar cardiac halofantrine and DHF enantiomer concentrations in rats were added together and correlated with QT interval, there was no appreciable strengthening (indeed weakening of the relationship in hyperlipidaemic rats) of the relationships (Table 2), which would not be expected if DHF was equipotent to halofantrine. The higher DHF to halofantrine ratios in plasma of normolipidaemic rats may have reflected either a preferential uptake into lipoproteins of parent drug than metabolite and/or a decreased rate of metabolism of halofantrine to DHF secondary to a decreased expression of CYP3A or 2C11 in hyperlipidaemic rats (Shayeganpour et al., 2008).

In patients free of drugs known to extend the QT interval, elevated concentrations of LDL cholesterol were associated with an increase in the QT interval (Szabo et al., 2005). Similarly, in rabbits given extended diets of cholesterol for up to 16 weeks, a prolongation was observed in the QT interval (Ander et al., 2004). In heart transplant patients treated with statins for one year, a reduction in LDL cholesterol was associated with a reduction in the QT interval (Vrtovec et al., 2006). In our rats hyperlipidaemia did not result in longer QT by itself, but it did accentuate the QT prolonging effect of halofantrine (Table 1). This is an interesting finding. Patients infected with P. falciparum have elevated plasma TGs, the levels of which were positively associated with the severity of the infection (Parola et al., 2004). Similarly, another study showed that malaria resulted in significantly higher plasma levels of total cholesterol, TG, LDL and VLDL, and lower levels of high density lipoproteins (Krishna et al., 2009). In combination with our findings in rat, this raises the possibility of hyperlipidaemia contributing to the QT interval prolongation caused by halofantrine in patients. The lack of prolongation in hyperlipidaemic control rats may have been due to a relatively short duration of hyperlipidaemia (days vs. the weeks or months in patients), or perhaps a difference in cardiac electrophysiology between rats and humans. More study is needed to examine this issue.

Our findings are not in agreement with those of McIntosh et al. (2004), who reported a lack of QTc interval prolongation after halofantrine administration to anesthetized rabbits, given a single short-term (30 min) intravenous soybean emulsion (McIntosh et al., 2004). The reason for this disparity is not clear, although study designs were very different. Although soybean emulsion does increase serum lipid concentrations, it is more likely to mimic a post-prandial rather than a hyperlipidaemic condition. Furthermore, because the lipid micelles are introduced with an absence of embedded apoproteins, their handling by the body probably differs from chylomicron particles or other lipoprotein classes. Because a chronic high fat diet can lead to hypercholesterolemia and a prolonged QT interval in rabbits (Ander et al., 2004), the lack of prolongation in QT observed by McIntosh et al. in response to halofantrine seems not due to the species used, but perhaps other aspects (study duration, dosing, anaesthesia, ventilation, etc.) of their experimental design, as outlined above and in the Introduction.

The morphology of the rat QT interval differs from that in humans, the difference likely being due to a species-difference in the ion channels involved in regulation of potassium flux. Although rats are thought to be devoid of IKr channels, it has been reported (Wymore et al., 1997) that the rat does express some degree of functional IKr in the ventricles. Regardless of the difference in cardiac physiology between species, it is apparent that in small rodent species such as rat (Table 1; Figure 4), and in mice (Batchu et al., 2009), halofantrine can cause a concentration-related prolongation of the QT interval, that is similar to that observed in other species including humans.

To summarize, the prolongation of the QT interval by halofantrine enantiomers was enhanced in the P407 rodent model of hyperlipidaemia, despite similar heart concentrations in normolipidaemic and hyperlipidaemic rats. In hyperlipidaemia, the plasma concentrations of halofantrine enantiomers were substantially higher after repeated doses. Uptake of the drug by heart tissues was apparently controlled by the unbound fraction of the drug in plasma. Although the data were not conclusive, based on the regression analysis, there was no evidence supporting the possibility that DHF could cause a significant prolongation of the QT interval in the rat.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (MOP 87395).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DHF

desbutylhalofantrine

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- P407

poloxamer 407

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglyceride

- VLDL

very low density lipoprotein

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Abernethy DR, Wesche DL, Barbey JT, Ohrt C, Mohanty S, Pezzullo JC, et al. Stereoselective halofantrine disposition and effect: concentration-related QTc prolongation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51:231–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.00351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Altered lipid metabolism in brain injury and disorders. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:241–268. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8831-5_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliabadi HM, Spencer TJ, Mahdipoor P, Lavasanifar A, Brocks DR. Insights into the effects of hyperlipoproteinemia on cyclosporine A biodistribution and relationship to renal function. AAPS J. 2006;8:E672–E681. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ander BP, Weber AR, Rampersad PP, Gilchrist JS, Pierce GN, Lukas A. Dietary flaxseed protects against ventricular fibrillation induced by ischemia-reperfusion in normal and hypercholesterolemic rabbits. J Nutr. 2004;134:3250–3256. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MA. Epidemiology of hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:13F–16F. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basco LK, Gillotin C, Gimenez F, Farinotti R, Le Bras J. In vitro activity of the enantiomers of mefloquine, halofantrine and enpiroline against Plasmodium falciparum. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;33:517–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1992.tb04081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basco LK, Peytavin G, Gimenez F, Genissel B, Farinotti R, Le Bras J. In vitro activity of the enantiomers of N-desbutyl derivative of halofantrine. Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45:45–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchu SN, Law E, Brocks DR, Falck JR, Seubert JM. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid prevents postischemic electrocardiogram abnormalities in an isolated heart model. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey AJ, Coker SJ. Proarrhythmic potential of halofantrine, terfenadine and clofilium in a modified in vivo model of torsade de pointes. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1003–1012. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont JL, Carlson LA, Cooper GR, Fejfar Z, Fredrickson DS, Strasser T. Classification of hyperlipidaemias and hyperlipoproteinaemias. Bull World Health Organ. 1970;43:891–915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchaud O, Imbert P, Touze JE, Dodoo AN, Danis M, Legros F. Fatal cardiotoxicity related to halofantrine: a review based on a worldwide safety data base. Malar J. 2009;8:289. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocks DR. A high-performance liquid chromatographic assay for the determination of desbutylhalofantrine enantiomers in rat plasma. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2001;4:24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocks DR. Stereoselective halofantrine and desbutylhalofantrine disposition in the rat: cardiac and plasma concentrations and plasma protein binding. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2002;23:9–15. doi: 10.1002/bdd.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocks DR, Toni JW. Pharmacokinetics of halofantrine in the rat: stereoselectivity and interspecies comparisons. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1999;20:165–169. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199904)20:3<165::aid-bdd170>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocks DR, Wasan KM. The influence of lipids on stereoselective pharmacokinetics of halofantrine: Important implications in food-effect studies involving drugs that bind to lipoproteins. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91:1817–1826. doi: 10.1002/jps.10182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocks DR, Dennis MJ, Schaefer WH. A liquid chromatographic assay for the stereospecific quantitative analysis of halofantrine in human plasma. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1995;13:911–918. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01343-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocks DR, Ala S, Aliabadi HM. The effect of increased lipoprotein levels on the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine A in the laboratory rat. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2006;27:7–16. doi: 10.1002/bdd.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung NS, Wasan KM. Potential role of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family as mediators of cellular drug uptake. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1315–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duntas LH, Wartofsky L. Cardiovascular risk and subclinical hypothyroidism: focus on lipids and new emerging risk factors. What is the evidence? Thyroid. 2007;17:1075–1084. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot LA, Jamali F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nifedipine in untreated and atorvastatin-treated hyperlipidemic rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot LA, Foster RT, Jamali F. Effects of hyperlipidemia on the pharmacokinetics of nifedipine in the rat. Pharm Res. 1999;16:309–313. doi: 10.1023/a:1018896912889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima K, Shibata M, Mizuhara K, Aoyama H, Uchisako R, Kobuchi S, et al. Effect of serum lipids on the pharmacokinetics of atazanavir in hyperlipidemic rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2009;63:635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genest J, Frohlich J, Fodor G, McPherson R. Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia and the prevention of cardiovascular disease: summary of the 2003 update. CMAJ. 2003;169:921–924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharavi N, Sattari S, Shayeganpour A, El-Kadi AO, Brocks DR. The stereoselective metabolism of halofantrine to desbutylhalofantrine in the rat: evidence of tissue-specific enantioselectivity in microsomal metabolism. Chirality. 2007;19:22–33. doi: 10.1002/chir.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez F, Gillotin C, Basco LK, Bouchaud O, Aubry AF, Wainer IW, et al. Plasma concentrations of the enantiomers of halofantrine and its main metabolite in malaria patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46:561–562. doi: 10.1007/BF00196116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy DA, Brocks DR. Experimental Hyperlipidemia Causes an Increase in the Electrocardiographic Changes Associated With Amiodarone. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;53:1–8. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31819359d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegele RA. Plasma lipoproteins: genetic influences and clinical implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:109–121. doi: 10.1038/nrg2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humberstone AJ, Cowman AF, Horton J, Charman WN. Effect of altered serum lipid concentrations on the IC50 of halofantrine against Plasmodium falciparum. J Pharm Sci. 1998a;87:256–258. doi: 10.1021/js970279q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humberstone AJ, Porter CJ, Edwards GA, Charman WN. Association of halofantrine with postprandially derived plasma lipoproteins decreases its clearance relative to administration in the fasted state. J Pharm Sci. 1998b;87:936–942. doi: 10.1021/js9704846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbwang J, Na Bangchang K. Clinical pharmacokinetics of halofantrine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1994;27:104–119. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199427020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbwang J, Milton KA, Na Bangchang K, Ward SA, Edwards G, Bunnag D. Pharmacokinetics of halofantrine in Thai patients with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:484–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb05567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Park SY, Chae WS, Jin HC, Lee JS, Kim YI. Effect of desflurane at less than 1 MAC on QT interval prolongation induced by tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:150–157. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisberg RA. Diabetic dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:67U–73U. 85U–86U. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00848-0. discussion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kris-Etherton PM, Krummel D, Russell ME, Dreon D, Mackey S, Borchers J, et al. The effect of diet on plasma lipids, lipoproteins, and coronary heart disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 1988;88:1373–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna AP, Chandrika KS, Acharya M, Patil SL. Variation in common lipid parameters in malaria infected patients. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;53:271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Palmer WK, Johnston TP. Disposition of poloxamer 407 in rats following a single intraperitoneal injection assessed using a simplified colorimetric assay. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1996;14:659–665. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein AH, Kennedy E, Barrier P, Danford D, Ernst ND, Grundy SM, et al. Dietary fat consumption and health. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:S3–S19. S19–S28. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01728.x. discussion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightbown ID, Lambert JP, Edwards G, Coker SJ. Potentiation of halofantrine-induced QTc prolongation by mefloquine: correlation with blood concentrations of halofantrine. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:197–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Kloosterman JM, Maitland AH, Klungel OH, Porsius AJ, de Boer A. Drug-Induced lipid changes: a review of the unintended effects of some commonly used drugs on serum lipid levels. Drug Saf. 2001;24:443–456. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbai M, Rajamani S, January CT. The anti-malarial drug halofantrine and its metabolite N-desbutylhalofantrine block HERG potassium channels. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:799–805. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh MP, Batey AJ, Porter CJ, Charman WN, Coker SJ. Desbutylhalofantrine: evaluation of QT prolongation and other cardiovascular effects after intravenous administration in vivo. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41:406–413. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh MP, Batey AJ, Coker SJ, Porter CJ, Charman WN. Evaluation of the impact of altered lipoprotein binding conditions on halofantrine induced QTc interval prolongation in an anaesthetized rabbit model. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56:69–77. doi: 10.1211/0022357022520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton KA, Edwards G, Ward SA, Orme ML, Breckenridge AM. Pharmacokinetics of halofantrine in man: effects of food and dose size. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monlun E, Le Metayer P, Szwandt S, Neau D, Longy-Boursier M, Horton J, et al. Cardiac complications of halofantrine: a prospective study of 20 patients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:430–433. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosten F, ter Kuile FO, Luxemburger C, Woodrow C, Kyle DE, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, et al. Cardiac effects of antimalarial treatment with halofantrine. Lancet. 1993;341:1054–1056. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92412-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owczuk R, Wujtewicz MA, Sawicka W, Piankowski A, Polak-Krzeminska A, Morzuch E, et al. The effect of intravenous lidocaine on QT changes during tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:924–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer WK, Emeson EE, Johnston TP. Poloxamer 407-induced atherogenesis in the C57BL/6 mouse. Atherosclerosis. 1998;136:115–123. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza F, D'Introno A, Colacicco AM, Capurso C, Pichichero G, Capurso SA, et al. Lipid metabolism in cognitive decline and dementia. Brain Res Rev. 2006;51:275–292. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P, Gazin P, Patella F, Badiaga S, Delmont J, Brouqui P. Hypertriglyceridemia as an indicator of the severity of falciparum malaria in returned travelers: a clinical retrospective study. Parasitol Res. 2004;92:464–466. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-1012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JP, Fleischer JG, Wasan KM, Brocks DR. The effect of experimental hyperlipidemia on the stereoselective tissue distribution, lipoprotein association and microsomal metabolism of (+/-)-halofantrine. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:2516–2528. doi: 10.1002/jps.21607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic V, Puddey IB, Dimmitt SB, Burke V, Beilin LJ. A controlled trial of the effects of pattern of alcohol intake on serum lipid levels in regular drinkers. Atherosclerosis. 1998;137:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JC, Proctor SD. Small animal models of cardiovascular disease: tools for the study of the roles of metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2006;15:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayeganpour A, Jun AS, Brocks DR. Pharmacokinetics of Amiodarone in hyperlipidemic and simulated high fat-meal rat models. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2005;26:249–257. doi: 10.1002/bdd.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayeganpour A, Lee SD, Wasan KM, Brocks DR. The influence of hyperlipoproteinemia on in vitro distribution of amiodarone and desethylamiodarone in human and rat plasma. Pharm Res. 2007;24:672–678. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayeganpour A, Korashy H, Patel JP, El-Kadi AO, Brocks DR. The impact of experimental hyperlipidemia on the distribution and metabolism of amiodarone in rat. Int J Pharm. 2008;361:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugioka N, Haraya K, Maeda Y, Fukushima K, Takada K. Pharmacokinetics of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor, nelfinavir, in poloxamer 407-induced hyperlipidemic model rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:269–275. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo Z, Harangi M, Lorincz I, Seres I, Katona E, Karanyi Z, et al. Effect of hyperlipidemia on QT dispersion in patients without ischemic heart disease. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:847–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Sakai J, Fujino T, Miyamori I, Yamamoto TT. The very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) receptor – a peripheral lipoprotein receptor for remnant lipoproteins into fatty acid active tissues. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;248:121–127. doi: 10.1023/a:1024184201941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tie H, Walker BD, Singleton CB, Valenzuela SM, Bursill JA, Wyse KR, et al. Inhibition of HERG potassium channels by the antimalarial agent halofantrine. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1967–1975. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrtovec B, Stojanovic I, Radovancevic R, Yazdanbakhsh AP, Thomas CD, Radovancevic B. Statin-associated QTc interval shortening as prognostic indicator in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner C, Krane V. Uremia-specific alterations in lipid metabolism. Blood Purif. 2002;20:451–453. doi: 10.1159/000063557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner C, Quaschning T. Dyslipidemia and renal disease: pathogenesis and clinical consequences. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10:195–201. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasan KM, Conklin JS. Enhanced amphotericin B nephrotoxicity in intensive care patients with elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:78–80. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasan KM, Kennedy AL, Cassidy SM, Ramaswamy M, Holtorf L, Chou JW, et al. Pharmacokinetics, distribution in serum lipoproteins and tissues, and renal toxicities of amphotericin B and amphotericin B lipid complex in a hypercholesterolemic rabbit model: single-dose studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3146–3152. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasan KM, Brocks DR, Lee SD, Sachs-Barrable K, Thornton SJ. Impact of lipoproteins on the biological activity and disposition of hydrophobic drugs: implications for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:84–99. doi: 10.1038/nrd2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesche DL, Schuster BG, Wang WX, Woosley RL. Mechanism of cardiotoxicity of halofantrine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;67:521–529. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.106127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NJ. Cardiotoxicity of antimalarial drugs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:549–558. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wout ZG, Pec EA, Maggiore JA, Williams RH, Palicharla P, Johnston TP. Poloxamer 407-mediated changes in plasma cholesterol and triglycerides following intraperitoneal injection to rats. J Parenter Sci Technol. 1992;46:192–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymore RS, Gintant GA, Wymore RT, Dixon JE, McKinnon D, Cohen IS. Tissue and species distribution of mRNA for the IKr-like K+ channel, erg. Circ Res. 1997;80:261–268. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]