Abstract

The interim between the first and tenth International Cholinesterase meetings has seen remarkable advances associated with the applications of structural biology and recombinant DNA methodology to our field. The cloning of the cholinesterase genes led to the identification of a new super family of proteins, termed the α,β–hydrolase fold; members of this family possess a four helix bundle capable of linking structural subunits to the functioning globular protein. Sequence comparisons and three dimensional structural studies revealed unexpected cousins possessing this fold that, in turn, revealed three distinct functions for the α,β-hydrolase proteins. These encompass: (1) a capacity for hydrolytic cleavage of a great variety of substrates, (2) a heterophilic adhesion function that results in trans-synaptic associations in linked neurons, (3) a chaperone function leading to stabilization of nascent protein and its trafficking to an extracellular or secretory storage location. The analysis and modification of structure may go beyond understanding mechanism, since it may be possible to convert the cholinesterases to efficient detoxifying agents of organophosphatases assisted by added oximes. Also, the study of the relationship between the α,β–hydrolase fold proteins and their biosynthesis may yield means by which aberrant trafficking may be corrected, enhancing expression of mutant proteins. Those engaged in cholinesterase research should take great pride in our accomplishments punctuated by the series of ten meetings. The momentum established and initial studies with related proteins all hold great promise for the future.

Keywords: Acetylcholinesterase; butyrylcholinesterase; neuroligin; thyroglobulin; α,β-hydrolase fold proteins; oxime reactivation

1. Introduction

It is a great personal pleasure to attend the Xth International Cholinesterase Meeting and deliver an opening address, for the first meeting some 70 km from here is where I had the opportunity to meet many of the established leaders in the field: Miro Brzin, A.O. Zupančič, Eric Barnard, Keith Laidler, Norman Aldridge, and witness an infusion of younger scientists bringing new perspectives to the field (fig. 1). The latter included Jean Massoulie, Terry Rosenberry, Israel Silman, and Suzanne Bon. Indeed, these investigators, young at the time, have now left an indelible imprint on the field, not only in terms of their literature contributions, but also a lasting scientific legacy imbued in the individuals they have trained.

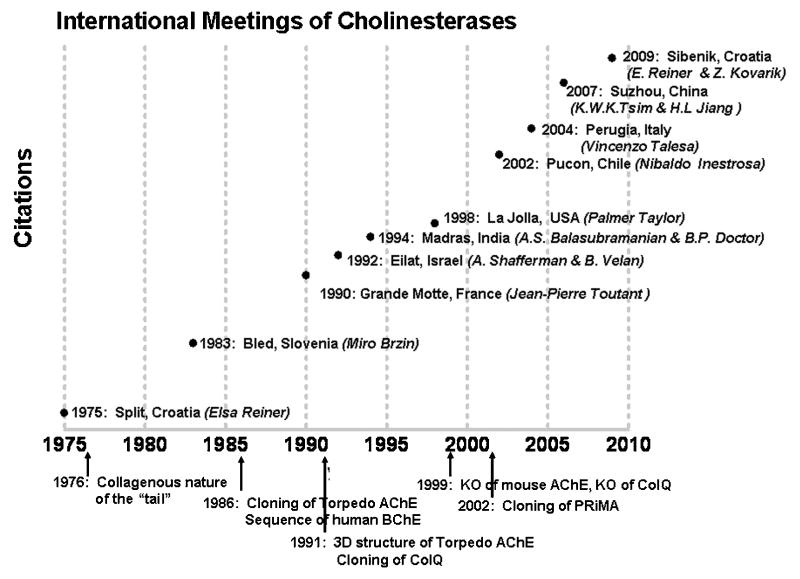

Figure 1. Global Geography of Cholinesterase Meetings.

The ten meetings have spanned the globe, but it is most fitting that the first and tenth meetings were less than 100 km apart.

In turn, much of their work, described in Split in 1975, emerged from prior contributions of Irwin Wilson, Felix Bergmann, Eric Barnard, Keith Laidler and Victor Whittaker. Indeed, we are fortunate to have Victor with us in Sibenik as well.

Unfortunately, only Terry and Suzanne could be with us this week, yet Jean and Israel will be connected in spirit, and cyberspace communication will enable them to receive details from the meeting in short order and well before this article emerges in print. We all wish them well, and look forward to their critiques and suggestions of scientific progress that we will learn about this week. Much of the acceleration in the field, along with the necessity of having frequent meetings on the subjects of abiding interest dear to our hearts, can be attributed to their contributions (fig. 2). This is well documented in the first book, and those of you with access to it should peruse its contents, for it still contains pearls for the young investigator starting in the field (fig. 3). In particular, the printed discussion provided the genesis of many of the studies that will be discussed today [1].

Figure 2. Cumulative Contributions in the Meeting Era.

A plot of the meetings and citations to acetylcholinesterase reveals a field still expanding in scope and perspective.

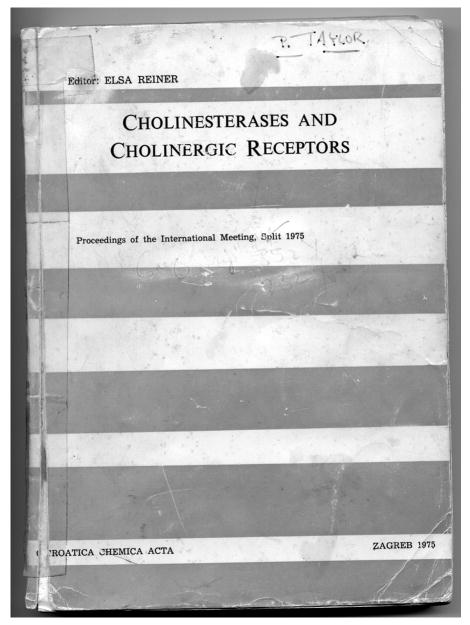

Figure 3. Meeting Proceedings in 1975.

The proceedings published in Croatica Chemica Acta chronicle some of the historical developments in the field. The meeting title is broader, but the emphasis was confined to the cholinesterases.

Over the 34 years intervening between Cholinesterase I and X, the linkages forged by Elsa Reiner have advanced cholinesterase research through her scientific outreach. Her scientific contributions related to catalysis and inhibition set the pace for continuing scientific rigor in the field. Despite the development of recombinant DNA technology, we continue to learn much from the fundamental character and relationships of the cholinesterases, as gene products. Elsa’s knack for organizing meetings that catalyze exchanges in the field and hasten new developments in our laboratories, should not be underestimated. In fact, it was the very success of these early cholinesterase meetings that spawned a sequence of topical meetings on ‘Cholinergic Function’ and on ‘Enzymes hydrolyzing Organophosphorus Compounds’. These meetings developed their own traditions, published proceedings, and a sustainable scientific continuity of their own.

Indeed, Elsa’s endeavors have outlasted prime ministers and country boundaries, allowing science to prevail even in times of political turmoil and beleaguered governments. While the distance is short between Split and Sibenik (fig. 1), the spirit of cooperation and collaboration continues to have global reach.

I hope to review some of the major advances in the field, admittedly not escaping a personal perspective. At the time of the 1975 meeting, cholinesterase was a widely studied enzyme, benefiting largely from its high turnover and through an alternate substrate, acetylthiocholine [2], being amenable to histochemical localization [3, 4]. However, at the 1975 meeting, contemporary molecular perspectives were emerging. Jean Massoulie had characterized the tail containing forms of AChE’s, and the first discussions of the collagen-like character emerged. Israel Silman had characterized the subunit organization of the Electrophorus enzyme, Terry Rosenberry had brought new perspectives to understanding catalysis through the use of alternative substrates and kinetic rigor. Our group had purified and characterized the enzyme from Torpedo californica, but little did we know at the time that it would become the staple for the first cloning of a cholinesterase, determining its sequence features [5] and ascertaining its crystal structure [6].

Since that time, the study of cholinesterases has brought many achievements to the fields of neurobiology and muscle biology-extending from the enzyme’s role in early life development to therapy in dementias associated with the aging process. Cholinesterase inhibitors are employed in therapeutic treatment of disease states, and cholinesterase reactivators have found application as antidotes to insecticide and nerve agent poisoning [7]. Indeed, these are contributions of many of the participants of the current meeting. Largely because of similarities in catalytic mechanisms and sequence relationships within the larger family of α,β-hydrolase-fold proteins [5, 8], the field has linked to other major advances with related proteins involved in adhesions in synaptic regions and in thyroid hormone production and secretion. Even though the cholinergic receptor field currently remains in vogue, because of variety of subtypes or the lack of fundamental knowledge on how channels function, cholinesterase has truly held its own as a neurobiological endeavor. Serendipity has conferred several unique characteristics to the cholinesterase gene and its gene product, but it has also been the sagacity of the investigators in the field that have uncovered details of genomes and proteomics relating the gene products to the larger frame work of chemistry at the interface of biology.

2. The Acetylcholinesterase Molecule and its Gene

About ten years after the Split meeting, the first cholinesterase sequence became available [5], and although prior data had identified the active center peptide, the sequence revealed a new motif for serine hydrolases, distinct from the trypsin and subtilisin families. Moreover, the then unexplained homology with thyroglobulin suggested a larger family of proteins with multiple functions. Soon thereafter, other cholinesterases and hydrolases fell into an enlarged family of proteins [9-13]. However, the structural perspective could not go beyond secondary structure until the first crystal structure of the Torpedo AChE emerged [6]. What this crystal structure revealed is that a unique sequence begot a novel structure, where catalysis is facilitated by the serine enlodged at the base of a narrow hydrophobic gorge. The gorge also established the surface topology for a peripheral site residing at its rim [14].

The homologous thyroglobulin sequence and soon that of bacterial and mammalian heterophilic adhesion proteins, revealed multiple functions for this family of proteins. Hence, the field immediately benefited from a template found in a common fold.

The cDNA then permitted cloning of genomic DNA [15] revealing that a single gene at 7q22 in man [16] encoded a uniform catalytic core, but variable means of membrane attachment and assembly to subunits that provided alternative means of membrane association and cellular disposition [15]. It also became evident that a single gene could subserve peripheral (autonomic and somatic motor) and central nervous systems that required over 10 identified subtypes of nicotinic receptors and 5 subtypes of muscarinic receptors for diversity of response. An enzyme with a proximal promoter region and three alternative splice profiles was discretely encoded in 7.5 kB of the total genome (fig. 4).

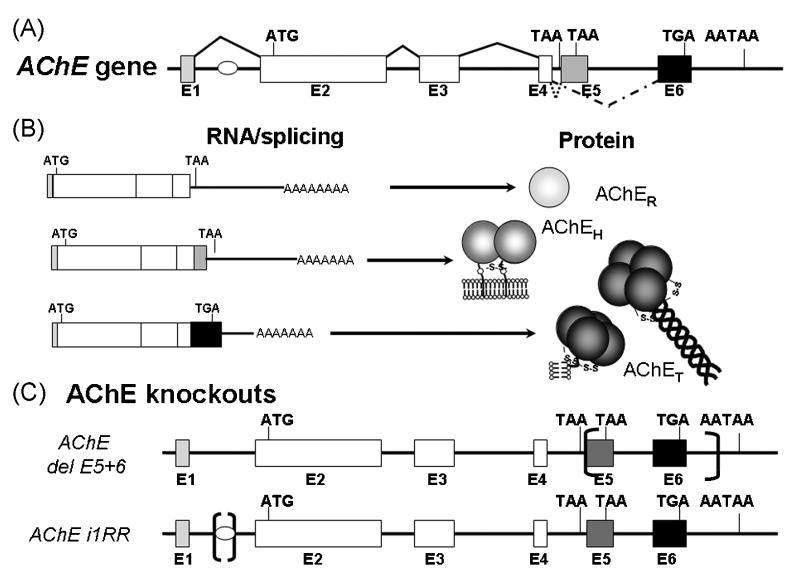

Figure 4. Gene Structure and Processing of Acetylcholinesterase.

A. The acetylcholinesterase gene in is found localized to 7.5kb in the human genome (NCBI Entrez Gene, Gene ID: 43), extending from a proximal promoter region through a most 3’ alternative splice in exon 6 to two alternatively used polyadenylation signals. The regulatory region found in the first intron is shown as a small oval. Invariant splicing is indicated by solid lines above the exons while alternative splicing in the 3’ end of the gene is indicated by dashed lines below the exons. B. Alternative splicing of the AChE gene. Exons 2-4 (in white) are invariantly spliced and form the catalytic core of the enzyme. Read through the 3’ donor in exon 4 produces the message that defines AChER. The message defined by the splice from exon 4 to exon 5 produces AChEH, the hydrophobic, glycophospholipid anchored form of the enzyme. The message containing the splice from exon 4 to exon 6 produces AChET, the enzyme that is found in brain and muscle which attaches to the anchoring subunits ColQ and PRiMA. C. AChE knockout mice. In the first AChE knockout strain, exons 2-5 were deleted, producing the AChE (-/-) mouse [20]. Other partial gene deletions have been made [21,22]. Here we show two of the deletions that produced knockout strains. Brackets indicate the locations of portions of the mouse AChE gene that were deleted.

Although a soluble, monomeric form of AChE can be generated by reading through from exon 4 to a stop codon (TGA or TAA), this form is in very low abundance in tissues. Splicing to exon 5 yields a glycophospholipid attached dimeric form of the enzyme, but the novel structural variants come from splicing to exon 6. This splice option yields a coiled-coil structure, termed the tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization (WAT) sequence that interacts with a proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD) found in the anchoring proteins, PRiMA and ColQ [17]. Attachment constitutes a means for associating with the plasma membrane through a single transmembrane span (PRiMA) [18] and to the basal lamina through a complex attachment to the triple helical strands of a collagen-like subunit (ColQ) [19]. Hence, localization within synapses is achieved through alternative splicing of the 3’ end of the open reading frame.

3. Regulation of AChE Gene Expression

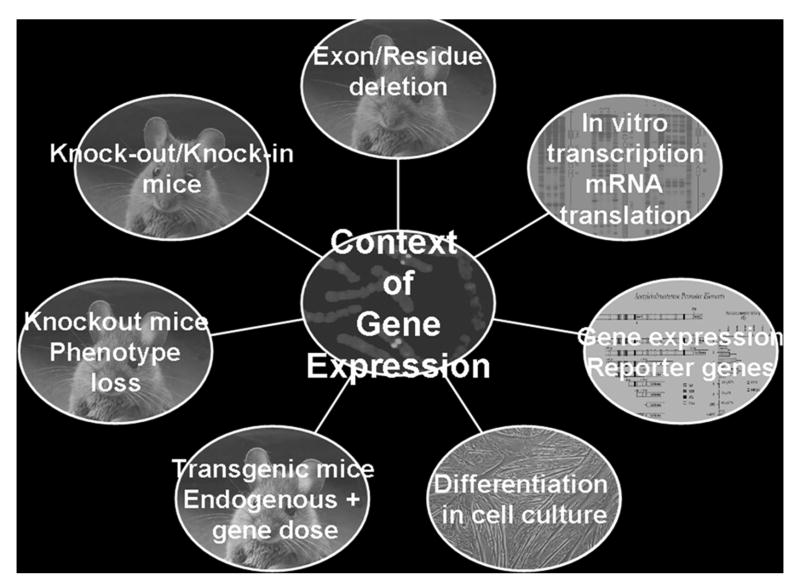

Understanding regulation of gene expression required going beyond in vitro studies of expression (fig. 5). Rather examination of expression in knock-out mice has been very informative for it has been possible to examine the consequences of elimination of the entire gene [20], alternative splice options [21, 22] as well as the structural subunits [23, 24]. Our understanding is currently more complete in muscle than in the nervous system. Contemporary studies of Eric Krejci, Oksana Lockridge, Shelley Camp and Hermona Soreq involving knock-out and transgenic animals are described in subsequent chapters in this volume.

Figure 5. Studies of Gene Expression.

Approaches start with the structure of the gene and involve the use of in vitro expression systems to measure transcriptional rates. Transcription and translation can be followed in cell culture, but such studies preclude examination in functioning synapses. In vivo studies may involve transgenic animals where additional copies of the gene are added to the mice genome, but suffer from indiscriminate gene incorporation into the genome. Knockout mice allow the study of a phenotype in the absence of a gene or portion of the gene, while knock-in strains provide the ability to alter a single residue in a protein, mimicking a genetically inherited disease.

Several remarkable features have emerged from the transgenic studies that had their foundations in studies of gene structure and gene expression in cellular systems. The first is the observation of Lockridge and colleagues [20] that AChE gene deletion is not a lethal mutation as found in Drosophila. While the knock-out mice are severely compromised, they can be nurtured through a shortened life span, but this is not sufficient for study of the knock-out phenotype. Subsequent studies have indicated that much of the compromised function is at the neuromuscular junction, whereas the CNS (brain and spinal cord) are able, through altered receptor density and production of acetylcholine, to maintain CNS function [25]. Second, control of expression in skeletal muscle and nerve occurs in different regions of the gene, where an enhancer region is found in muscle that controls expression at the neuromuscular junction [21]. These studies also reveal that AChE in the junction is a consequence of synthesis in muscle rather than motor neuron transporting AChE to the junction. Accordingly, selective knock-out mouse strains involving the structural subunits and individual exons have established the anatomic location, source of synthesis and the functional role of the forms of AChE [24], identified and characterized largely through the pioneering work of Jean Massoulie and colleagues [26]. It is also noteworthy that in neurons, the structural subunits play a trafficking role in the biosynthetic disposition of the AChE gene products and their disposition in synaptic areas [24].

4. From Inhibitor to Antidote through a Common Transition State

Studies of AChE catalysis and inhibition still present some challenges to the field. Computational studies provide an important touchstone for ferreting out the most viable experimental systems or technical approaches for resolving mechanisms of molecular recognition and chemical selectivity. Contributions based on three-dimensional structural analysis are reviewed by Joel Sussman, Israel Silman and their colleagues in a later manuscript in this volume. Further insights have been obtained from molecular modeling, as the McCammon laboratory has made AChE a prototype for ligand-protein interactions in general [27]. While it is unlikely that more selective cholinesterase inhibitors will advance the treatment of dementias, a need exists to design superior cholinesterase reactivators, since the alkylphosphates still are widely used as agricultural pesticides. Moreover, their ease of production and volatility confers properties for an insidious use in terrorism. The alkylphosphates, resembling the tetrahedral transition state of hydrolysis of a trigonal ester, react readily with cholinesterase forming a stable conjugate. The challenge for enhancing reactivation stems from reactivating the inhibited enzyme with an appropriate nucleophile. This reaction must proceed back through the pentahedral transition state, and the impacted gorge may preclude an optimal angle for oxime attack. Current work still follows the lead of site-directed oximes developed by Irwin Wilson over 50 years ago [28].

New variants on this theme relate to developing nucleophiles that cross the blood-brain barrier and thus can reactivate central AChE, thereby averting the seizures associated with acute cholinesterase inhibition in brain (Fig. 6). A second approach has been to scavenge the alkylphosphate in the plasma through the use of cholinesterase itself as a stoichiometric scavenger [29]. Increasing efficiency of scavenging would entail converting cholinesterase into a catalytic scavenger [30], or using other alkylphosphate hydrolyzing enzymes as catalytic scavengers. Much of the hope for progress here stems from knowing the structures of the cholinesterases and designing nucleophiles where site direction to the conjugated phosphorus atom is optimized. Unfortunately, the enzyme gorge is well designed for a tetrahedral phosphate to react with the active center serine, but spatial impaction by the conjugated organophosphate within the narrow gorge precludes reactivating nucleophiles obtaining an ideal angle or clearance for attack. Nevertheless, various groups are making substantive progress in the design of prophylactic and antidotal agents. Presentations by David Lenz, Richard Gordon, Zoran Radić and others at the meeting detail the inroads made in this area.

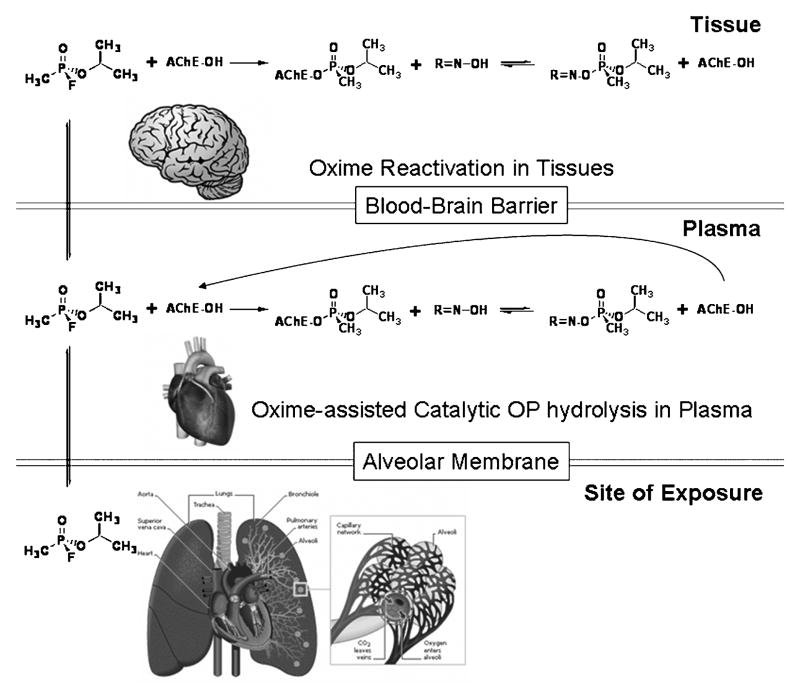

Figure 6. Approaches to Developing Superior Antidotes and Prophylactic Agents in Cholinesterase Inhibitor Poisoning.

Cholinesterase inhibitors in inadvertent poisoning and exposure situations gain access through the lungs and the skin. Distribution to susceptible tissues requires that these toxicants enter the circulatory system. A scavenging molecule in the blood could sequester or hydrolyze the alkylphosphate by hydrolysis before entry to the tissue. Oximes could also act by entering the tissues to reactivate inhibited enzyme. A non-ionized fraction or species of reactivator is required to cross the blood-brain barrier.

5. Structure and Functions of the α,β-Hydrolase-fold Super Family

Study of cholinesterase in relation to other homologous α,β-hydrolase fold proteins [31] suggests three functional roles for this super family of proteins (fig. 7). The obvious one, derived from the name of the superfamily, is the catalysis of hydrolytic reactions involving esters and amides. Wide substrate specificity, along with great variation in catalytic turnover potential, is achieved through both residue differences around the active center and the overall shape of the entry to the active center. In ester catalysis, rates extend from the very high turnover of AChE (10 μS) to the slow catalysis seen with juvenile hormone esterases [32].

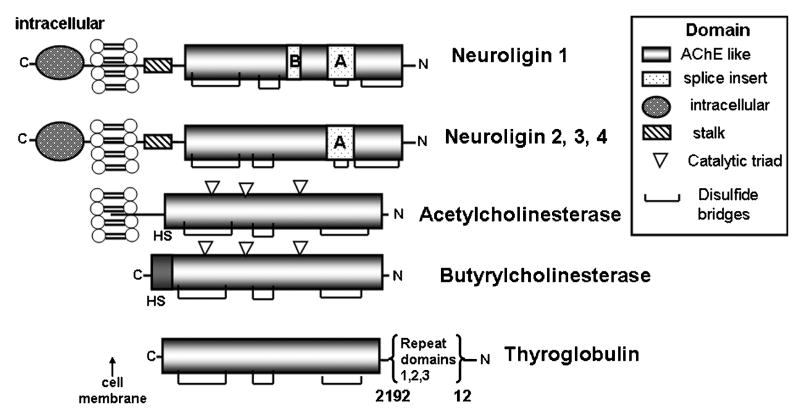

Figure 7. Comparison of Three Types of α,β-Hydrolase-fold Proteins with Distinct Structures and Functions.

The neuroligins (1-4), acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase, and thyroglobulin, among many other proteins share the use of the structural α,β-hydrolase-fold which has been shown to be critical in protein processing and trafficking.

A second function emerged with the discovery of homology of the tactin molecules to the esterases in the α,β-hydrolase fold, where proteins function not through catalysis, but rather through heterophilic adhesions with partnering molecules (fig. 8). The subsequent identification of a synaptic molecule in mammalian systems, neuroligin, that fell into this category prompted a more complete characterization of these synaptic molecules [33, 34], pointing to a recognition code between the neuroligins and the primary partnering proteins, the neurexins. The neuroligins and neurexins are single span trans-membrane proteins serving to create unique environments on both the synaptic and intracellular sides of the presynaptic and post-synaptic membranes (fig. 8).

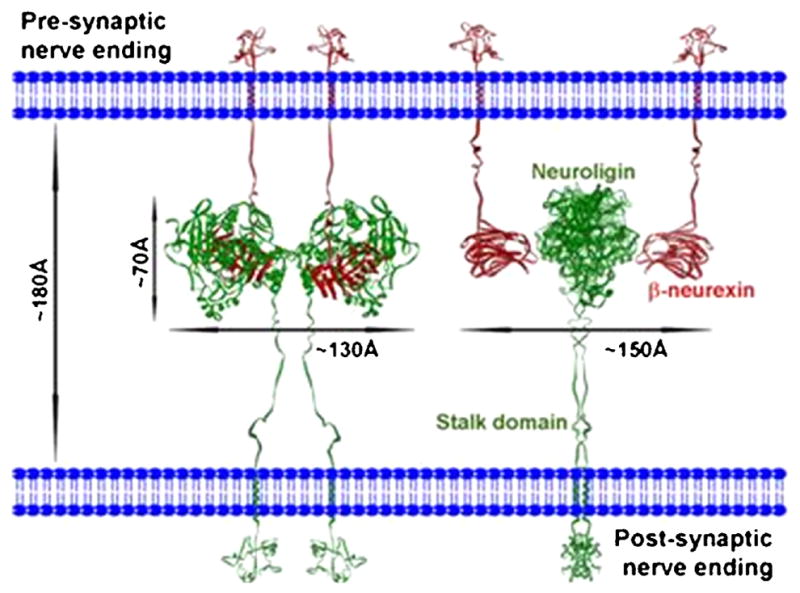

Figure 8. Neuroligin and Neurexin at the Synapse.

Structures of neuroligin and β-neurexin as determined from small angle x-ray, neutron scattering, and x-ray crystallography. The theoretical position of the neuroligin-neurexin complex with respect to the pre- and post-synaptic membranes is shown. Two views of the complex, one rotated by 90° from the other, are displayed. Neuroligin exists as a dimer with two neurexin molecules residing on opposing sides of the long axis. From [34], by permission.

The neuroligin dimer provides the focus point for the synaptic interaction of the neurexin molecules. The two neurexins bind on opposite sides of the long axis of neuroligin. Both neuroligin and neurexin are tethered to the membrane through an extended glycosylated strand that is likely to provide extension flexibility within the synapse should synaptic volumes or widths change (fig. 8) [35].

Through selective protein associations, unique environments are presented in individual synapses. For example, neuroligin 1 is found in excitatory amino acid synapses, while neuroligin 2 is associated with inhibitory hyperpolarizing synapses [36, 37]. Alternative splicing seen in the various neuroligins as well as differential glycosylation, confer additional determinants of selectivity giving rise to what becomes an intricate synaptic identity code [38].

Examining the cholinesterase homologous domain in neuroligin has revealed the absence of a catalytic triad subserving catalysis and the vestigial active center gorge lacks a patent entry or opening [39]. Interestingly, the location for the neurexin-neuroligin association is on the side opposite the active center gorge (fig. 9) [35, 39]. Hence, the adhesion function has separately evolved in this protein fold. The assembly of the four helix bundle to form dimers of the α,β-hydrolase fold provides the fundamental dimeric structure for neurexin binding on opposite sides of the long axis of the neuroligin dimer (fig. 8).

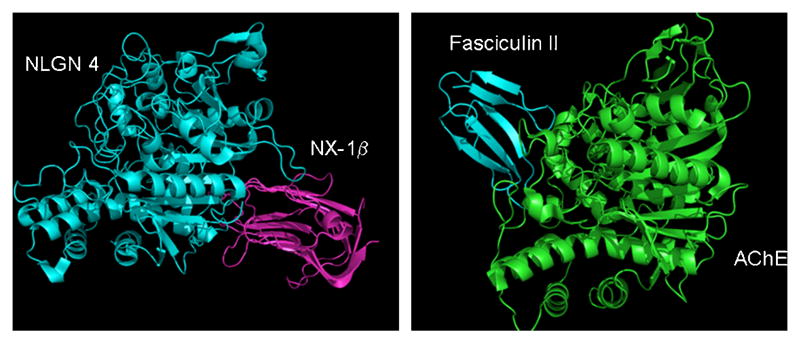

Figure 9. X-Ray Crystal Structures show that Neuroligin Binds to Neurexin at the Opposite face of the α,β-Hydrolase-fold Protein from the AChE-Fasciculin Interaction.

Neuroligin and neurexin are shown in the left panel, AChE and Fasciculin are shown on the right. The 4-helix bundle, involved in dimerization of both neuroligin and AChE is shown at the bottom of each panel. Fasciculin binds at the entry of the active center gorge, thereby precluding access of substrate to the active center. The peripheral site is part of the interface between the fasciculin molecule and the AChE gorge rim.

Finally, a third function appears to be emerging from the α,β-hydrolase fold proteins with the cholinesterase-like domain of thyroglobulin. From studies of Arvan and collaborators [40-43], the cholinesterase homologous (CHEL) domain serves a chaperone for the trafficking functions that are essential for processing the large thyroglobulin 1,2,3,domain to form thyroid hormones [40, 44]. Several mutations in the α,β-hydrolase fold sequence of thyroglobulin result in compromised trafficking of the molecule in the export process through the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi body. If dimerization is essential for export, then heteromeric dimers may still be functional and replacement chaperones might be considered as a means of controlling defective trafficking.

Similar trafficking deficiencies are also seen with neuroligin [45] raising the question whether the association between the autism spectrum disorders and polymorphisms in neuroligin [46] could be corrected by therapeutic modification with the appropriate chaperones.

6. Epilog and Summary

The path from Split to Sibenik has seen the cholinesterase field keep pace with the advances in recombinant DNA technologies and the emergence contemporary genomics. New protein cousins have impacted on understanding the role of synatogenesis and development as well as maintenance of “synaptic phenotypes”. Studies of cholinesterase inhibitors are evolving to the more difficult drug design considerations of reactivating antidotes and scavenging agents for nerve agent poisoning. Moreover, the recognition that the cholinergic system is one, but scarcely the sole, player in degenerative diseases raises new opportunities for combination therapy and consideration of trophic agents that may selectively influence expression of synaptic proteins. In short, the cholinesterase field has provided critical discoveries and translational developments that impact neurobiology, pharmacology and toxicology, yet more remains to be explored.

It certainly has been rewarding for me and my coworkers to have been part of these 34 years of development. Our contributions could not have been possible without the abiding interest and long standing, creative contributions of Zoran Radić and Shelley Camp. Their endeavors are well documented in the meeting proceedings. Moreover, colleagues that have collaborated with Zoran and Shelley will be important elements in defining the currents in fields related to cholinesterase and its cousins. Those of us who have participated in and continue to witness these developments would be hard pressed to imagine what the next 35 years will bring. Yet the group that has gathered in Sibenik can take pride in our perpetuating an expanding field of future endeavor.

Abbreviations

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- BChE

butyrylcholinesterase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References Cited

- 1.Reiner E, editor. Cholinesterases and Cholinergic Receptors. Croatica Chemica Acta; Split, Croatia: 1975. Proceedings of the International meeting on Cholinesterases and Cholinergic Receptors. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karnovsky MJ, Roots L. A “Direct-Coloring” Thiocholine Method for Cholinesterases. J Histochem Cytochem. 1964;12:219–221. doi: 10.1177/12.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koelle GB, Gromadzki CG. Comparison of the gold-thiocholine and gold-thiolacetic acid methods for the histochemical localization of acetylcholinesterase and cholinesterases. J Histochem Cytochem. 1966;14(6):443–454. doi: 10.1177/14.6.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schumacher M, Camp S, Maulet Y, Newton M, MacPhee-Quigley K, Taylor SS, Friedmann T, Taylor P. Primary structure of Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase deduced from its cDNA sequence. Nature. 1986;319(6052):407–409. doi: 10.1038/319407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sussman JL, Harel M, Frolow F, Oefner C, Goldman A, Toker L, Silman I. Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: a prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science. 1991;253(5022):872–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1678899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor P. Chapter 8. Anticholinesterase Agents. In: Brunton LL, editor. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ollis DL, Cheah E, Cygler M, Dijkstra B, Frolow F, Franken SM, Harel M, Remington SJ, Silman I, Schrag J, et al. The alpha/beta hydrolase fold. Protein Eng. 1992;5(3):197–211. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doctor BP, Chapman TC, Christner CE, Deal CD, De La Hoz DM, Gentry MK, Ogert RA, Rush RS, Smyth KK, Wolfe AD. Complete amino acid sequence of fetal bovine serum acetylcholinesterase and its comparison in various regions with other cholinesterases. FEBS Lett. 1990;266(1-2):123–127. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81522-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockridge O, Bartels CF, Vaughan TA, Wong CK, Norton SE, Johnson LL. Complete amino acid sequence of human serum cholinesterase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(2):549–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McTiernan C, Adkins S, Chatonnet A, Vaughan TA, Bartels CF, Kott M, Rosenberry TL, La Du BN, Lockridge O. Brain cDNA clone for human cholinesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(19):6682–6686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prody CA, Zevin-Sonkin D, Gnatt A, Goldberg O, Soreq H. Isolation and characterization of full-length cDNA clones coding for cholinesterase from fetal human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(11):3555–3559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rachinsky TL, Camp S, Li Y, Ekstrom TJ, Newton M, Taylor P. Molecular cloning of mouse acetylcholinesterase: tissue distribution of alternatively spliced mRNA species. Neuron. 1990;5(3):317–327. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90168-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourne Y, Taylor P, Radic Z, Marchot P. Structural insights into ligand interactions at the acetylcholinesterase peripheral anionic site. Embo J. 2003;22(1):1–12. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Camp S, Rachinsky TL, Getman D, Taylor P. Gene structure of mammalian acetylcholinesterase. Alternative exons dictate tissue-specific expression. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(34):23083–23090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getman DK, Eubanks JH, Camp S, Evans GA, Taylor P. The human gene encoding acetylcholinesterase is located on the long arm of chromosome 7. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51(1):170–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dvir H, Harel M, Bon S, Liu WQ, Vidal M, Garbay C, Sussman JL, Massoulie J, Silman I. The synaptic acetylcholinesterase tetramer assembles around a polyproline II helix. Embo J. 2004;23(22):4394–4405. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perrier AL, Massoulie J, Krejci E. PRiMA: the membrane anchor of acetylcholinesterase in the brain. Neuron. 2002;33(2):275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krejci E, Coussen F, Duval N, Chatel JM, Legay C, Puype M, Vandekerckhove J, Cartaud J, Bon S, Massoulie J. Primary structure of a collagenic tail peptide of Torpedo acetylcholinesterase: co-expression with catalytic subunit induces the production of collagen-tailed forms in transfected cells. Embo J. 1991;10(5):1285–1293. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie W, Stribley JA, Chatonnet A, Wilder PJ, Rizzino A, McComb RD, Taylor P, Hinrichs SH, Lockridge O. Postnatal developmental delay and supersensitivity to organophosphate in gene-targeted mice lacking acetylcholinesterase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293(3):896–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camp S, De Jaco A, Zhang L, Marquez M, De la Torre B, Taylor P. Acetylcholinesterase expression in muscle is specifically controlled by a promoter-selective enhancesome in the first intron. J Neurosci. 2008;28(10):2459–2470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4600-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camp S, Zhang L, Marquez M, de la Torre B, Long JM, Bucht G, Taylor P. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) gene modification in transgenic animals: functional consequences of selected exon and regulatory region deletion. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;157-158:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng G, Krejci E, Molgo J, Cunningham JM, Massoulie J, Sanes JR. Genetic analysis of collagen Q: roles in acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase assembly and in synaptic structure and function. J Cell Biol. 1999;144(6):1349–1360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobbertin A, Hrabovska A, Dembele K, Camp S, Taylor P, Krejci E, Bernard V. Targeting of acetylcholinesterase in neurons in vivo: a dual processing function for the proline-rich membrane anchor subunit and the attachment domain on the catalytic subunit. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(14):4519–4530. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3863-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler M, Manley HA, Purcell AL, Deshpande SS, Hamilton TA, Kan RK, Oyler G, Lockridge O, Duysen EG, Sheridan RE. Reduced acetylcholine receptor density, morphological remodeling, and butyrylcholinesterase activity can sustain muscle function in acetylcholinesterase knockout mice. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30(3):317–327. doi: 10.1002/mus.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massoulie J. The origin of the molecular diversity and functional anchoring of cholinesterases. Neurosignals. 2002;11(3):130–143. doi: 10.1159/000065054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng Y, Suen JK, Zhang D, Bond SD, Zhang Y, Song Y, Baker NA, Bajaj CL, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Finite element analysis of the time-dependent Smoluchowski equation for acetylcholinesterase reaction rate calculations. Biophys J. 2007;92(10):3397–3406. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.102533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson IB. Acetylcholinesterase. XIII. Reactivation of alkyl phosphate-inhibited enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1952;199(1):113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saxena A, Maxwell DM, Quinn DM, Radic Z, Taylor P, Doctor BP. Mutant acetylcholinesterases as potential detoxification agents for organophosphate poisoning. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54(2):269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor P, Kovarik Z, Reiner E, Radic Z. Acetylcholinesterase: converting a vulnerable target to a template for antidotes and detection of inhibitor exposure. Toxicology. 2007;233(1-3):70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hotelier T, Renault L, Cousin X, Negre V, Marchot P, Chatonnet A. ESTHER, the database of the alpha/beta-hydrolase fold superfamily of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D145–147. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCutchen BF, Uematsu T, Szekacs A, Huang TL, Shiotsuki T, Lucas A, Hammock BD. Development of surrogate substrates for juvenile hormone esterase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;307(2):231–241. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ichtchenko K, Hata Y, Nguyen T, Ullrich B, Missler M, Moomaw C, Sudhof TC. Neuroligin 1: a splice site-specific ligand for beta-neurexins. Cell. 1995;81(3):435–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sudhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455(7215):903–911. doi: 10.1038/nature07456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comoletti D, Grishaev A, Whitten AE, Tsigelny I, Taylor P, Trewhella J. Synaptic arrangement of the neuroligin/beta-neurexin complex revealed by X-ray and neutron scattering. Structure. 2007;15(6):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cline H. Synaptogenesis: a balancing act between excitation and inhibition. Curr Biol. 2005;15(6):R203–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craig AM, Kang Y. Neurexin-neuroligin signaling in synapse development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comoletti D, Flynn RE, Boucard AA, Demeler B, Schirf V, Shi J, Jennings LL, Newlin HR, Sudhof TC, Taylor P. Gene selection, alternative splicing, and post-translational processing regulate neuroligin selectivity for beta-neurexins. Biochemistry. 2006;45(42):12816–12827. doi: 10.1021/bi0614131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fabrichny IP, Leone P, Sulzenbacher G, Comoletti D, Miller MT, Taylor P, Bourne Y, Marchot P. Structural analysis of the synaptic protein neuroligin and its beta-neurexin complex: determinants for folding and cell adhesion. Neuron. 2007;56(6):979–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park YN, Arvan P. The acetylcholinesterase homology region is essential for normal conformational maturation and secretion of thyroglobulin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):17085–17089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim PS, Lee J, Jongsamak P, Menon S, Li B, Hossain SA, Bae JH, Panijpan B, Arvan P. Defective protein folding and intracellular retention of thyroglobulin-R19K mutant as a cause of human congenital goiter. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(2):477–484. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Jeso B, Ulianich L, Pacifico F, Leonardi A, Vito P, Consiglio E, Formisano S, Arvan P. Folding of thyroglobulin in the calnexin/calreticulin pathway and its alteration by loss of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J. 2003;370(Pt 2):449–458. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menon S, Lee J, Abplanalp WA, Yoo SE, Agui T, Furudate S, Kim PS, Arvan P. Oxidoreductase interactions include a role for ERp72 engagement with mutant thyroglobulin from the rdw/rdw rat dwarf. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6183–6191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608863200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, Lee J, Di Jeso B, Treglia AS, Comoletti D, Dubi N, Taylor P, Arvan P. Cis and trans actions of the cholinesterase-like domain within the thyroglobulin dimer. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.111641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Jaco A, Comoletti D, Kovarik Z, Gaietta G, Radic Z, Lockridge O, Ellisman MH, Taylor P. A mutation linked with autism reveals a common mechanism of endoplasmic reticulum retention for the alpha,beta-hydrolase fold protein family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(14):9667–9676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vono-Toniolo J, Kopp P. Thyroglobulin gene mutations and other genetic defects associated with congenital hypothyroidism. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2004;48(1):70–82. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302004000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]