Abstract

PDZ domains are members of the protein interaction domain family,[1] semi-autonomous modules embedded within larger signaling proteins that impart a degree of exclusivity to the binding properties of their hosts. As mediators of mammalian protein-protein interactions that number in the hundreds, PDZ domains are party to a correspondingly large array of cellular processes, most notably those that regulate or support neuronal activities.[2] Specific, bioavailable molecular probes are needed to foster biological inquiries into their functions; towards this end, we report our recent progress in the discovery and development of PDZ domain inhibitors.

Keywords: Calorimetry, combinatorial chemistry, NMR spectroscopy, peptides, protein domains

Here the focus is on the protein postsynaptic density 95 (PSD-95), which bears three PDZ domains. Abundant in neurons, PSD-95 serves as a nexus for transient interactions that affect core synaptic events, such as transmission and plasticity.[3, 4] Inhibitors that selectively uncouple these PDZ domain-promoted associations will greatly assist in determining their exact roles. Further, disrupting these interactions of PSD-95 could constitute novel therapeutic avenues for treatment of stroke and ischemic brain damage[5] and other excitotoxic disorders.[6]

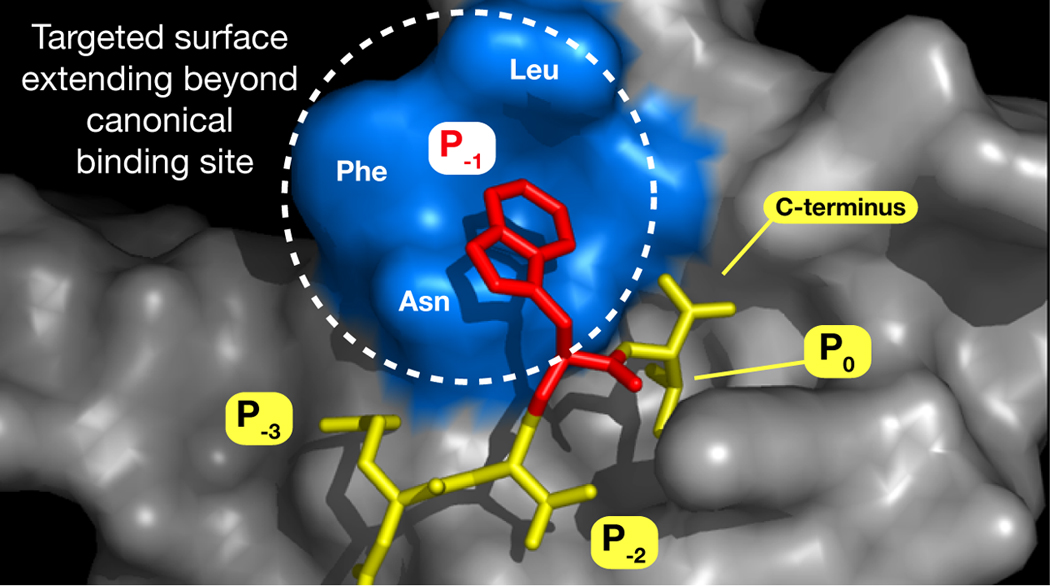

We expand upon prior work in which linear peptide ligands were developed for the third PDZ domain (PDZ3) of PSD-95.[7] Data from that investigation, in conjunction with an X-ray crystal structure we solved of PDZ3 bound to the hexapeptide KKETWV (PDB ID 1TP5), indicate that the binding site occupied by the side chain of the penultimate C-terminal residue (Figure 1, position P−1) can accommodate a variety of organic substructures. We hypothesized that suitable elaboration of a side chain within that site—and perhaps even just beyond its perimeter—might enhance existing interactions and possibly accrue new ones.

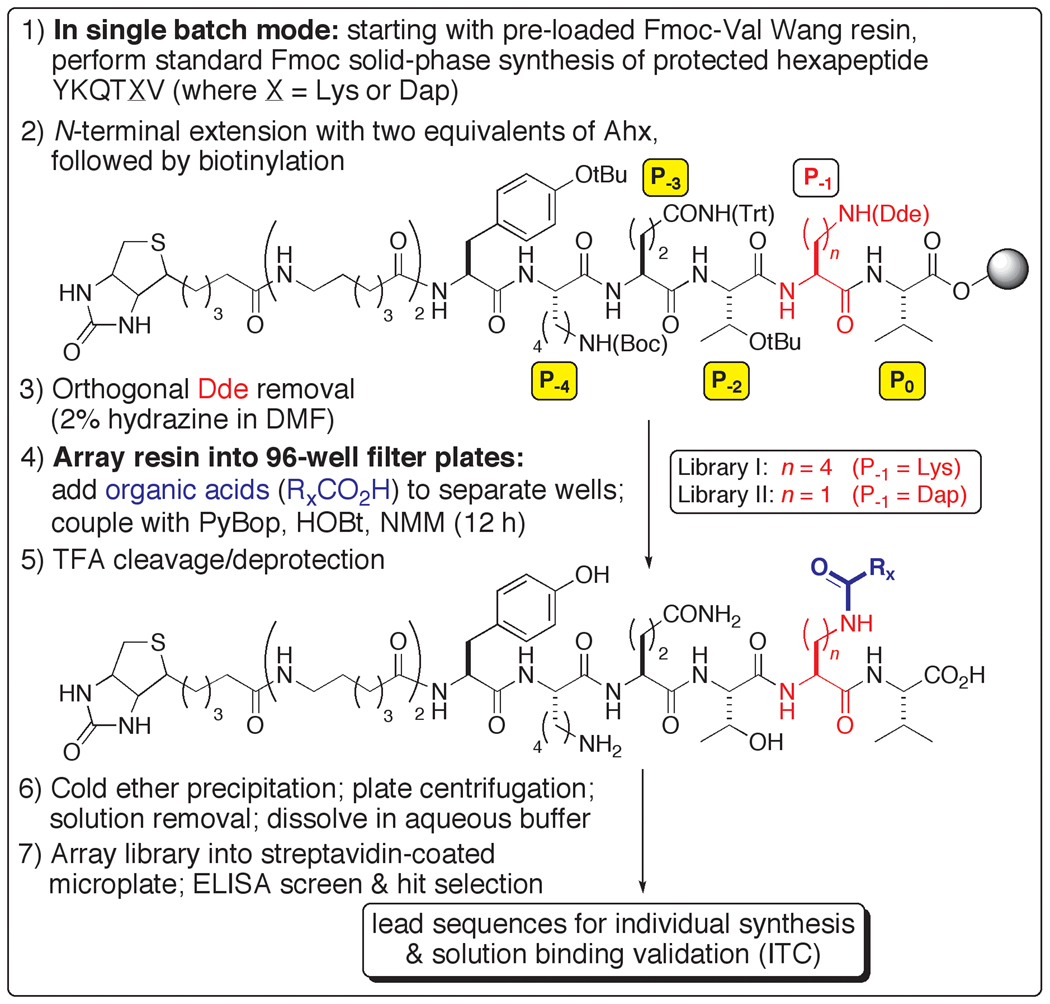

Figure 1.

Structure-based design rationale for organic-modified libraries for PSD-95 PDZ3, based on the complex between PDZ3 and KKETWV. Positions P0 and P−2 denote conserved primary binding determinants. P−1, occupied by Trp, will be replaced by Lys acylated with organic acids. Blue surface represents a 6Å-region encircling the Trp indole.

A ligand design strategy was devised, built upon a parallel chemical synthesis platform, in which a diverse collection of organic acids was used to individually acylate an amino side chain at P−1 of a peptide ligand for PDZ3 (Scheme 1). This approach was inspired by a library-based peptide modification protocol, in which consensus sequences have been iteratively transformed into high affinity ligands.[8] As originally reported, however, the methodology does not allow for display and screening of the unmodified peptide C-terminus (a strict requirement for most PDZ domain binding events), and a significantly redeveloped scheme was implemented for our studies.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis and screening of C-terminal-displayed organic-modified libraries for PSD-95 PDZ3.

Two chemical libraries were prepared, templated upon a different hexapeptide, YKQTSV, which we had previously demonstrated to exhibit slightly higher affinity than KKETWV for PDZ3.[7] The acyl acceptor at P−1 comprised lysine (Library I) or diaminopropionic acid (Dap) (Library II), replacing the original residue at that position (Scheme 1). Sets of 92 (Library I) and 186 (Library II) organic acids were used, which were selected to reflect a range of functionality and carbogenic character (alkyl and aryl). Between the variable length of the donor arms and the organic structural diversity presented, the expectation was that modified ligands might be discovered that would possess improvements in affinity, target specificity and in vivo (proteolytic) stability. For this pilot inquiry, the focus was to first evaluate leads based strictly on the criterion of binding strength.

An ELISA-type assay was developed to screen the two libraries, in which the direct binding of a GST-PDZ3 fusion protein was detected via a standard dual antibody system (see Supporting Information). The top scoring sequences (Figure 2) were individually synthesized on preparative scale without N-terminal extensions, and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was used to measure their solution binding parameters with PDZ3 (Table 1).

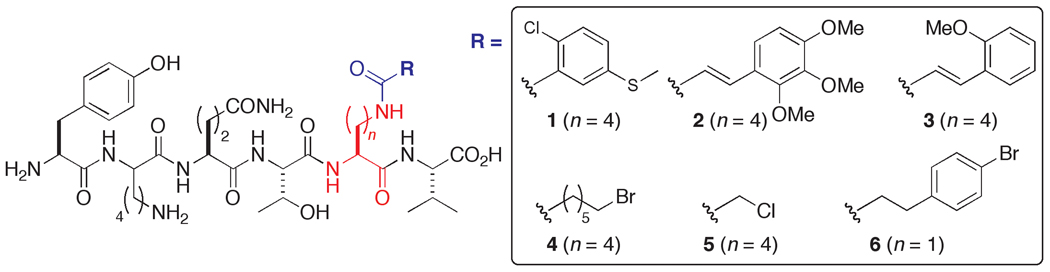

Figure 2.

Organic-modified peptides for PSD-95 PDZ3 prepared based on selected sequences from screening Libraries I (ligands 1–5) and II (ligand 6).

Table 1.

Thermodynamic binding parameters of organic-modified peptide ligands and PDZ3 of PSD-95.[a

| Ligand | Kd (µM) |

ΔG (kcal/mol) |

ΔH (kcal/mol) |

TΔS (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YKQTKV | 6.3 (± 1.1) | −7.1 (± 0.1) | −4.1 (± 0.1) | 3.0 (± 0.1) |

| 1 | 0.55 (± 0.1) | −8.6 (± 0.1) | −5.9 (± 0.1) | 2.7 (± 0.1) |

| 2 | 1.5 (± 0.1) | −7.9 (± 0.1) | −4.4 (± 0.1) | 3.5 (± 0.1) |

| 3 | 1.4 (± 0.1) | −8.0 (± 0.1) | −4.5 (± 0.1) | 3.5 (± 0.1) |

| 4 | 2.2 (± 0.6) | −7.7 (± 0.2) | −3.6 (± 0.1) | 4.1 (± 0.1) |

| 5 | 2.0 (± 0.2) | −7.8 (± 0.1) | −4.1 (± 0.1) | 3.7 (± 0.1) |

| 6 | 0.33 (± 0.1) | −8.9 (± 0.1) | −5.3 (± 0.1) | 3.6 (± 0.1) |

Values are the arithmetic mean of at least two independent experiments (error shown beside each value reflects the range).

All six of the modified ligands exhibit improved affinity over the unmodified parent peptide YKQTKV, with dissociation constants in the low- to submicromolar range. The upper end is marked by an almost 20-fold enhancement for 6, with the addition of an aryl bromide to Dap. Of note is that the next tightest binder, 1, bears a chlorinated aryl sulfide, with the aromatic ring of almost equal bond count distance from the backbone. These two ligands, deriving from different libraries, may thus represent convergence towards a discrete region of the protein surface in which favorable binding interactions can occur. Similarly, the slightly lowered affinity pair of compounds 2 and 3 may also reflect a salutary outcome for aromatic positioning in a more distal location

Examining ligand 1 further, the Kd of 0.55 µM equates to a full order of magnitude improvement in affinity over that of YKQTKV. While the addition of the chlorinated aromatic ring might implicate a hydrophobic effect with an energetically favorable release of water, this is not necessarily in accord with the observation that the change in free energy is attributable solely to enthalpy (ΔΔH = 1.8 kcal/mol). This suggests the formation of discrete, specific molecular interactions with the protein surface, attributable to the added organic acid moiety.

The metamorphosis of YKQTKV to 1 successfully evades the annoying phenomenon of enthalpy-entropy compensation,[9] in which structural modification of a ligand yields energetic gains made in binding enthalpy that are offset by a comparable unfavorable loss in binding entropy (or vice-versa). While 1 does experience a small decrease in entropy, it subtracts little from the large ΔH value that is almost fully transferred to ΔG.

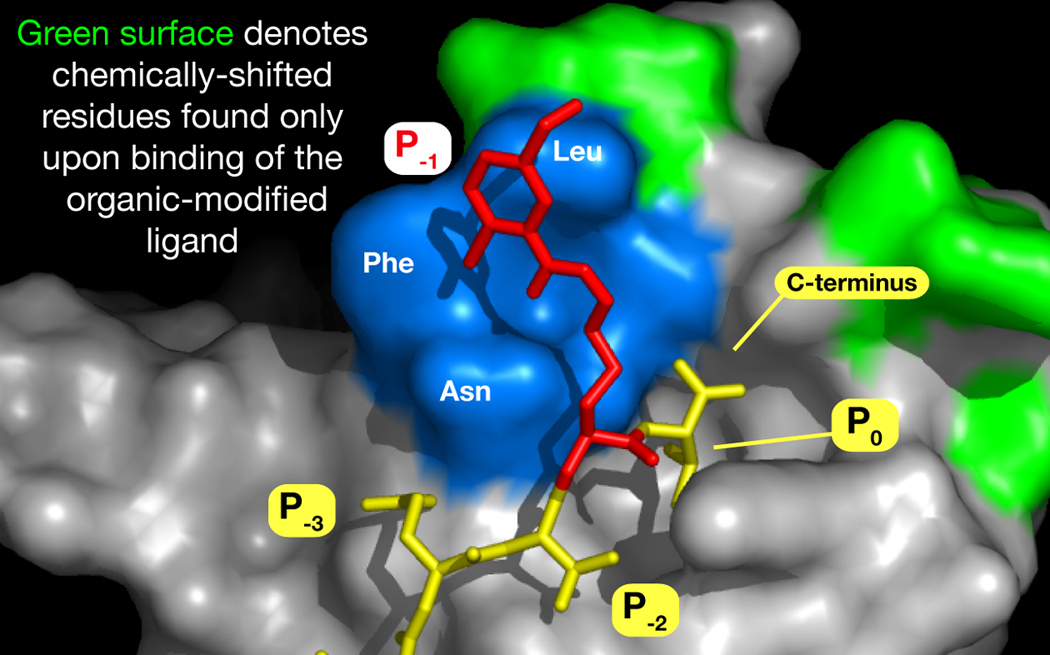

To probe the nature of the interaction between ligand 1 and PDZ3, we turned to protein NMR and conducted HSQC chemical shift perturbation experiments.[10] Separate titrations of 15N isotopically-labeled PDZ3 with 1 and with unmodified YKQTKV revealed that while the binding of both generated chemical shifts from residues within the established P−1 site, ligand 1 evoked additional responses from regions just beyond the demonstrated binding pocket (Figure 3). This was accompanied by similar unique shifts in a more apical position to the C-terminus. In both cases, such shifts may connote direct residue interactions, as well as those that are propagated through conformational motions. In either event, this provides preliminary support to our conjecture that such organic-modified ligands can access protein-binding modes that a native peptide cannot.

Figure 3.

Model of 1 side chain (red) supplanting that of Trp in the KKETWV-PDZ3 structure. Positioning of the side chain of 1 is not energetically minimized, and intended only to portray the potential extent of occupancy. Differential HSQC chemical shifts upon binding that are unique to 1 are mapped onto residues of the PDZ3 structure (green).

In summary, our design strategy as executed has led to potent compounds directed towards a PDZ domain of prime neurobiological importance. The success achieved here lays the foundation for future expansions of this work; in addition to (1) increasing the number of organic acids used, these include (2) placement of acylation sites at P−4 and beyond, thus allowing for iterative additions for multiple organic modifications on a single backbone; (3) the use of other amino-side chain donor residues of variable length (such as ornithine), to further explore the molecular recognition space of the protein surface; and, of particular significance, (4) application to other PDZ domains. Considering the scarcity of small binding ligands for these proteins, this last point is especially attractive, since many PDZ domains adhere to a common modular binding formula that can be rapidly exploited by the extensible approach presented here.

Experimental Section

Detailed procedures for conducting the synthetic, assay and HSQC experiments are provided in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Timothy Stemmler and Krisztina Bencze (WSU School of Medicine) for assistance with the HSQC experiments. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM63021).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chembiochem.org

References

- 1.Pawson T, Nash P. Science. 2003;300:445–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1083653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim E, Sheng M. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:771–781. doi: 10.1038/nrn1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beique JC, Andrade R. J Physiol. 2003;546:859–867. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beique JC, Lin DT, Kang MG, Aizawa H, Takamiya K, Huganir RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19535–19540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608492103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aarts M, Liu Y, Liu L, Besshoh S, Arundine M, Gurd JW, Wang YT, Salter MW, Tymianski M. Science. 2002;298:846–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1072873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui H, Hayashi A, Sun HS, Belmares MP, Cobey C, Phan T, Schweizer J, Salter MW, Wang YT, Tasker RA, Garman D, Rabinowitz J, Lu PS, Tymianski M. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9901–9915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1464-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saro D, Li T, Rupasinghe C, Paredes A, Caspers N, Spaller MR. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6340–6352. doi: 10.1021/bi062088k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence DS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharp K. Protein Sci. 2001;10:661–667. doi: 10.1110/ps.37801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao G, Williams JG, Campbell SL. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;261:79–92. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-762-9:079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.