Abstract

An experiment tested the pathways through which alcohol expectancies and intoxication influenced men’s self-reported sexual aggression intentions during an unprotected sexual encounter. After a questionnaire session, male social drinkers (N = 124) were randomly assigned to either an alcohol condition (target peak BAC = .08%) or a control condition. Upon completion of beverage consumption, participants read a description of a sexual encounter in which the female partner refused to have unprotected sexual intercourse. Participants then rated their emotional state, their intentions to have unprotected sex with the unwilling partner, and their post-incident perceptions of the encounter. Structural equation modeling indicated that intoxicated men reported feeling stronger sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations such as arousal and anger; however, this effect was moderated by alcohol expectancies. Intoxicated participants with stronger alcohol-aggression expectancies reported greater sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations than did intoxicated participants with weaker alcohol-aggression expectancies. For sober participants, alcohol-aggression expectancies did not influence emotions/motivations. In turn, stronger sexual assault congruent emotions/motivations predicted greater sexual aggression intentions. Men with greater sexual aggression intentions were less likely to label the situation as a sexual assault and reported less concern about their intended actions. These findings underscore the relevance of both alcohol expectancies and alcohol intoxication to sexual aggression perpetration and highlight the importance of including information about alcohol’s influence on both emotional and cognitive responses in sexual aggression prevention work.

Key Terms: Sexual Aggression, Alcohol, Unprotected Sex, Alcohol Expectancies

Two of the major public health challenges involve sexual behavior: sexual violence and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Regarding sexual violence, approximately 80% of women experience sexual assault during their lifetimes (Koss, 1988), while approximately 25% of women experience rape or attempted rape (Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987). Results from the National Violence against Women Survey estimate that over 300,000 women are raped in the United States each year, typically by a man known to them (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). Surveys indicate that up to 64% of men report some form of sexual assault perpetration since the age of 14 (Abbey, Parkhill, BeShears, Clinton-Sherrod, & Zawacki, 2006). Regarding STIs, the Centers for Disease Control estimate that 19 million new infections occur each year (CDC, 2009), and that more than half of all people will contract an STI during their lifetimes (Koutsky, 1997).

Sexual Aggression and Risky Sexual Behavior

Research indicates that these sexual behaviors may not be entirely independent from one another (Amaro, 1995; Abbey, Parkhill, Jacques-Tiura, & Saenz, 2009). For example, men who have perpetrated violence against women are less receptive to condom requests from their female partners (Neighbors, O’Leary, & Labouvie, 1999; Neighbors & O’Leary, 2003) and are significantly more likely to report inconsistent or no condom use during vaginal and anal sexual intercourse than men who have not perpetrated intimate partner violence (Raj et al., 2006). An online survey of heterosexual men found that sexually aggressive men engaged in more sexual risk taking than their non-aggressive counterparts (Peterson, Janssen, & Heiman, 2009). Moreover, research also indicates that sexually aggressive acts often do not involve condom use (Davis, Schraufnagel, George, & Norris, 2008; Peterson et al., 2009; Raj et al., 2006). In sum, global and event-level research has demonstrated linkages between sexual aggression and sexual risk. The present study explores these linkages by examining processes that may occur in situations involving sexual aggression during unprotected sexual behavior.

Alcohol, Sexual Aggression, and Risky Sexual Behavior

One contributing factor to this nexus of sexual risk is alcohol. Alcohol consumption is often present in situations that involve aggressive or risky sexual behavior (George & Stoner, 2000). Research has consistently found a positive global association between alcohol use and risky sexual behavior (Cooper, 2002), with alcohol’s role in men’s risky sexual behavior primarily occurring in situations involving recent casual sexual partners, rather than new or regular sexual partners (LaBrie, Earleywine, Schiffman, Pedersen, & Marriot, 2005). Similarly, survey research implicates alcohol consumption in sexual aggression against women, with a majority of the perpetrators having consumed alcohol prior to committing sexual assault (Testa, 2002).

Experimental investigations of alcohol’s influence on sexual aggression and sexual risk intentions provide further evidence for this relationship. Controlled laboratory conditions allow for establishing a causal connection between these variables. Using either written, audio, or video-based hypothetical sexual encounters, laboratory studies have consistently found that after alcohol is administered to participants, intoxicated men report greater sexually aggressive intentions toward a hypothetical female partner than their sober counterparts (Davis, Norris, George, Martell, & Heiman, 2006; Marx, Gross, & Juergens, 1997; Norris, Davis, George, Martell, & Heiman, 2002). Experimental investigations similarly indicate that acute alcohol intoxication increases men’s risky sexual intentions (George et al. 2009; Gordon, Carey, & Carey, 1997; MacDonald, Fong, Zanna, & Martineau, 2000; MacDonald, MacDonald, Zanna, & Fong, 2000; MacDonald, Zanna, & Fong, 1996). Moreover, Abbey and colleagues (Abbey et al., 2009) found that when drinking, men with either greater hostility or with stronger tendencies to misperceive women’s intentions reported feeling more justified in using coercive techniques to obtain unprotected sex than did sober men.

Alcohol Myopia Effects

Alcohol myopia models (Steele & Josephs, 1990) explain the effects that alcohol-induced cognitive impairment has on behavior. In these models, cues that instigate behavior are typically described as more immediate and concrete than inhibitory cues, which are often more removed and abstract (Steele & Josephs, 1990). Due to alcohol-induced cognitive deficits, an intoxicated individual would only be able to process to the more salient instigatory cues and would thus be more likely to engage in the specified behavior than would an unimpaired sober person. Applied to risky or aggressive sexual behavior, alcohol myopia theory predicts that intoxicated men’s decreased cognitive capacity focuses their attention on instigatory cues, such as sexual arousal or affective state, while impairing their perception and interpretation of inhibitory cues, such as the woman’s sexual refusal or the absence of a condom. This cognitive focus then renders them more likely to engage in risky or aggressive sexual behavior (Davis, Hendershot, George, Norris, & Heiman, 2007; Testa, 2002). Experimental studies involving the administration of alcohol to participants have provided support for these predictions. In an experiment by Gross and colleagues, intoxicated men had a greater focus on instigatory female sexual arousal cues than did sober men, resulting in delayed decisions that a hypothetical male character should stop his unwanted sexual advances (Gross, Bennett, Sloan, Marx, & Juergens, 2001). Regarding risky sexual behavior, experimental studies have found that intoxicated participants reported stronger intentions to have unprotected intercourse, and that this effect was mediated by an increased focus on sexual arousal cues (Davis et al., 2007).

Alcohol Expectancy Effects

Alcohol Expectancy Theory contends that alcohol consumption may also influence behavior through individuals’ outcome expectancies about alcohol’s emotional, physiological, and behavioral effects, which are often influenced by larger cultural beliefs about alcohol-related outcomes (MacAndrew & Edgerton, 1969). Alcohol expectancy theory posits that alcohol consumption results in increased sexually aggressive and risky behavior due to commonly held beliefs in our society that alcohol increases sexual arousal, sexual behavior in general, risky sexual behavior, and sexual aggression (Abbey, McAuslan, Ross, & Zawacki, 1999; Dermen & Cooper, 1994). Thus, these behaviors are viewed as more normative when performed under the influence of alcohol.

Some experimental studies have attempted to disentangle alcohol dosage set effects from physiological effects through the use of a placebo condition. Although some studies have found significant placebo effects on dependent sexual aggression measures, these effects are typically much smaller than those for actual alcohol consumption (Marx et al., 1997; Marx, Gross & Adams, 1999), and the majority of studies have not found significant placebo effects for sexual aggression-related dependent measures (e.g. Johnson, Noel, & Sutter Hernandez, 2000; Norris, George, Davis, Martell, & Leonesio, 1999; Norris & Kerr, 1993) or for risky sexual behavior (e.g. MacDonald et al., 1996; Fromme, D’Amico, & Katz, 1999; Maisto et al., 2004; Abbey, Saenz, & Buck, 2005; Testa et al., 2006). Moreover, studies have shown that the placebo manipulation is a more effective control for low dose (BAC < .04 %) than high dose alcohol conditions; when placebo participants are instructed to expect a high dose and are accordingly given increased non-alcoholic beverage amounts, the probability of manipulation failures dramatically increases (Martin & Sayette, 1993). Placebo conditions may also result in unanticipated compensatory effects in which individuals in the placebo condition effectively utilize strategies that negate alcohol’s potential effects (Testa et al., 2006). Given the inconsistent placebo effects, the difficulties of successfully manipulating placebo conditions at higher expected alcohol doses, and the possible compensatory effects associated with placebo conditions, the current study focused on self-reported alcohol outcome expectancies (and their interaction with acute intoxication) to assess expectancy effects.

Several previous studies have found main effects for self-reported alcohol outcome expectancies, such that individuals with stronger expectancies about alcohol’s effects on risky sexual behavior often report greater risky sex intentions than individuals with weaker alcohol expectancies (e.g. Abbey et al., 2005; Gordon et al., 1997). Regarding the influence of self-reported alcohol expectancies on sexually aggressive behavior, Norris et al. (2002) found that men with stronger sex-related alcohol expectancies reported greater sexual aggression intentions as mediated by greater sexual and affective responding to an eroticized rape depiction involving alcohol. Similarly, men with stronger beliefs about women’s sexual vulnerability when drinking reported greater sexual arousal to an eroticized, alcohol-involved rape depiction, which in turn predicted greater estimates of their sexual aggression likelihood (Davis et al., 2006). Thus, beliefs that alcohol necessitates a particular sexual response or emotional state in situations involving alcohol may generate a self-fulfilling prophecy in which the outcome beliefs result in a greater likelihood of the behavior in question (George & Stoner, 2000).

Moreover, expectancies and alcohol myopia processes are not mutually exclusive (Morris & Albery, 2001; Moss & Albery, 2009) in that pre-existing expectancies may moderate the effects of intoxication on mediating factors and behavioral intentions. For example, Davis et al. (2007) found that when intoxicated, individuals’ expectations steer their myopic attention towards stimuli compatible with their expectancies, such that individuals who expected unprotected sexual intercourse to result in primarily positive consequences were more likely, when intoxicated, to attend to stimuli instigating risky sexual behavior. Norris et al. (2002) found that sex-related alcohol expectancies moderated the effects of intoxication on men’s self-reported sexual aggression likelihood such that intoxicated men with strong alcohol expectancies reported greater sexual aggression likelihood than did men sober men with strong alcohol expectancies. Thus, individual differences in expectations have been shown to moderate the influence of the myopic effects of alcohol intoxication in some laboratory studies regarding both risky and aggressive sexual intentions.

The Role of Emotion and Motivation

Research has shown that emotional arousal in general, and the emotional state of anger in particular, may facilitate aggressive behavior (Rule & Nesdale, 1976) and may also be associated with less willingness to use condoms after a partner has requested to do so (Otto-Salaj et al., 2009). Additionally, the state of sexual arousal has been shown to increase men’s sexual aggression intentions (Loewenstein, Nagin, & Paternoster, 1997) and decrease men’s likelihood of using condoms (Ariely & Loewenstein, 2006) compared to those of non-aroused men. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that this increase in sexual arousal mediates the relationship between alcohol intoxication and greater sexual aggression intentions (Davis et al., 2006) and also mediates the relationship between alcohol intoxication and unprotected sex intentions (George et al., 2009). Similarly, irritability, which includes hostile attitudes and impulsive actions (Caprara et al., 1985), has also been shown to mediate the effects of alcohol on aggression (Godlaski & Giancola, 2009). Although impulsivity as related to sexual aggression has typically been examined through assessments of dispositional impulsive tendencies (e.g. Zawacki, Abbey, Buck, McAuslan, & Clinton-Sherrod, 2003), numerous studies have demonstrated that impulsivity is also state-dependent in that impulsive behavior typically increases during states of acute alcohol intoxication (e.g. Dougherty, Marsh, Moeller, Chokshi, & Rosen, 2000). Sexual offenders themselves also cite impulsive urges and feelings as reasons for their perpetration of sexual aggression (Mann & Hollin, 2007). Similarly, the need to feel in control and powerful is often cited by perpetrators of sexual assault as a motivation for their actions (e.g. Mann & Hollin, 2007; Scully & Marolla, 1985). Thus, the current work examines what we have termed “sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations”, which includes anger, sexual arousal, impulsivity, and power to assess whether these factors mediate the effects of alcohol on men’s use of sexual aggression to obtain unprotected sex.

Study Overview and Hypotheses

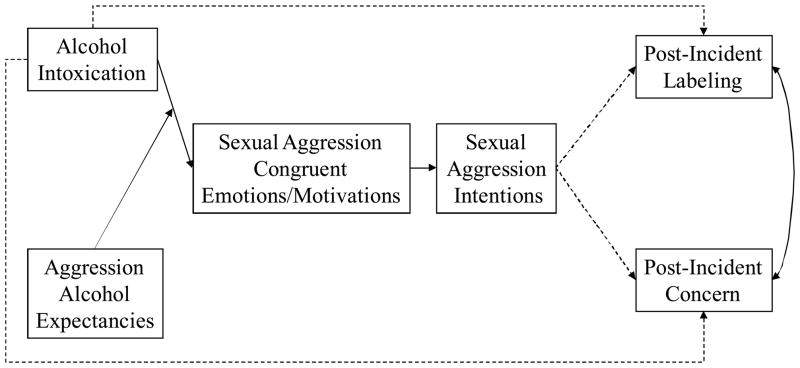

The present study used experimental methodology to examine effects of alcohol consumption and alcohol expectancies related to aggression on men’s emotional reactions to a hypothetical sexual scenario in which the female sex partner refused to engage in unprotected sexual intercourse, as well as their subsequent self-reported likelihood of engaging in unprotected sexual intercourse with the unwilling partner. A structural equation modeling approach was used to examine the relationships among alcohol intoxication, aggression-related alcohol expectancies, sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations, sexual aggression intentions, and post-incident labeling and reactions to the incident. The proposed model (see Figure 1) hypothesizes that intoxicated men, particularly those with stronger alcohol expectancies regarding aggression, would report greater sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations than sober men. Additionally, it was hypothesized that as participants’ sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations increased, so would their intentions to commit sexually aggressive acts. Men with stronger sexual aggression intentions were expected to be less concerned about their actions and less likely to label them as “rape” than men with weaker sexual aggression intentions. Because prior work has indicated that alcohol’s influence on both aggressive and unprotected sexual intentions are completely mediated by its effects on affective factors such as sexual arousal (e.g. Davis et al., 2006; George et al., 2009), direct effects of alcohol on sexual aggression intentions were not anticipated. However, research indicates that alcohol intoxication can directly increase men’s perceptions of sexual assault as more justified, more typical, less deviant, and less violent (Norris, Martell, & George, 2001); thus, direct effects of alcohol intoxication on participants’ post-incident reactions were hypothesized. Intoxicated men were expected to be less likely than sober men to feel concerned about their actions and to label them as “rape”.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model. Solid lines represent positive relationships; dotted lines represent negative relationships.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 124) were recruited from the community at large through online and print advertisements which stated that male social drinkers were wanted for a study on “decision-making.” Potential participants called the laboratory and were screened to determine whether they were eligible to participate. Inclusion criteria were that the individual had to be (a) between the ages of 21 and 30; (b) interested in dating opposite-sex partners; (c) not currently in a committed dating relationship; (d) a moderate social drinker; and (e) a heavy episodic drinker (had consumed 5 or more drinks in one episode within the past six months). Exclusion criteria were current or historical problem drinking (as defined by a score of 5 or more on the Brief Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test; Pokorny, Miller, & Kaplan, 1972) and/or currently taking medications or having a health condition contraindicating alcohol consumption. Participants’ mean age was 24.56 years (SD = 2.82).

Participants were predominantly European American (69.7%); 5.7% were African American, 7.4% were Asian American, 1.6% were Native American, and 15.6% were multi-racial or other. Additionally, Hispanic/Latino ethnic identity was reported by 6.6% of participants. Approximately two-thirds (65.3%) were employed. Participants reported consuming an average of 15.56 drinks per week (SD = 11.22) and reported an average of 3.44 sexual partners in the past year (SD = 4.07).

Procedure

Pre-experimental instructions

During the screening phone call, participants were instructed to bring photo identification, not to drive to the laboratory, not to eat or consume caloric drinks for three hours before their appointments, and not to drink alcohol or use recreational or over-the-counter drugs for 24 hours before their appointments.

Initial procedures

Each participant was assigned a male experimenter to conduct the study procedures. Upon arrival, each participant was escorted to a private room, where the experimenter administered an initial breath test with an Alco-Sensor IV (Intoximeters Inc., St. Louis, MO) to ascertain a zero reading. After confirming pre-experimental instruction compliance, the experimenter obtained informed consent. Participants were trained to answer questions on the computer, and then left alone to complete background questionnaires.

Beverage administration

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two beverage conditions (alcohol or control beverage). All participants were informed of the actual content of their drinks. Based on previously published dosing procedures (George et al., 2009), each participant was weighed to determined the amount of 100-proof vodka needed to achieve a peak blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of .08%, with participants receiving .82 g ethanol/kg body weight. Drinks consisted of one part vodka to three parts orange juice. Control participants drank a volume of orange juice equivalent to what they would have received in the alcohol condition. Beverages were divided into three equal portions, and participants consumed each portion over a period of 3 minutes for a total of 9 minutes. The experimenter regularly informed the participants of the amount of time elapsed so that they could pace their consumption evenly over the 9 minute period.

In order to ensure that participants completed the risk assessment while on the ascending limb of alcohol intoxications, their BACs were tested every four minutes until they reached a criterion level (BAC ≥ .045%), at which point they began the experimental protocol. Alcohol participants had a mean BAC of .056% (SD = .012) prior to reading the stimulus story; their mean BAC after the completion of the dependent measures was .085% (SD = .011). Mean BAC of the control participants was .00% (SD = .00) throughout the protocol. A yoked control design was used to reduce error variance in time between beverage consumption and experimental manipulation (Giancola & Zeichner, 1997; Schacht, Stoner, George, & Norris, 2010), such that control participants were yoked to an alcohol participant who had already participated, and were breathalyzed and began the experimental manipulation at the same time intervals as did the alcohol participants to whom they had been yoked.

Sexual risk assessment

After the BAC criterion was met, participants read a hypothetical scenario described below involving a sexual encounter with a casual sex partner where no condom was available. Participants completed dependent measures after they completed reading the story.

Detoxification and debriefing

After completing the sexual risk assessment, control participants were debriefed, paid, and released. Alcohol participants were escorted to another room, where they remained until their BAC dropped to .03% or below, at which point they were debriefed, paid, and released. All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Measures and Materials

Pretest measures

Participants completed a demographics questionnaire that assessed age, ethnicity, and other pertinent information. In addition, they completed the Alcohol Expectancies Regarding Sex, Aggression, and Sexual Vulnerability Questionnaire (Abbey et al., 1999) that consisted of 75 items answered on a 5-point scale (1= not at all to 5 = very much). The current analyses only used the subscale pertaining to men’s beliefs regarding alcohol’s effects on their own aggression. This subscale consisted of 7 items relating to participants’ engagement in aggression when drinking (α = .90; M = 1.94, SD = .73), such as when drinking alcohol, I am likely to hit or slap.

Sexual risk-taking assessment

Participants read a 1600-word hypothetical sexual scenario written in the second person at approximately a 5th grade reading level that described a third-time sexual encounter with a casual sex partner. Participants were instructed to envision themselves acting as the protagonist of the story at their current level of intoxication (Davis, George, & Norris, 2004). The vignette was sexually explicit in order to increase the likelihood that it would be sexually arousing. Interviews with pilot participants (n = 20) confirmed that they found the scenario to be realistic, sexually arousing, and easily comprehended.

In the story, the participant attends a party with a platonic friend named Rob. Upon arrival at the party, the participant sees a woman named Kim with whom he has sex a couple of times before. The participant and Kim engage in conversation and flirting. As the party winds down, Kim and the participant go to her home, where the couple begins kissing and engaging in foreplay. The story indicates that they had previously used condoms both times they had sex. To emphasize HIV/STI risk over pregnancy risk, the story stipulated that the female character used hormonal contraceptives. After engaging in foreplay, they realize that neither of them have a condom. Kim states that they “should not go all the way without a condom” but is initially willing to continue kissing and other activities. As the sexual activity continues and eventually becomes more intimate, Kim emphatically states that she does not want to have sex without a condom while also pushing the protagonist away. Dependent measures were then assessed. Participants reported finding this scenario to be a realistic situation (I feel that the scenario depicted a realistic situation that might happen to me; 1 = not at all; 5 = very much; M = 3.54; SD = 1.40).

Sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations

Participants rated their current emotional and motivational responses to the story on a five-point Likert scale (e.g. 1 = not at all; 5 = extremely). Participants were instructed to “Please rate how much you feel each of the following emotions at this time in the story”. They were then given 19 items to rate, each of which represented an emotional/motivations state that could be congruent with the perpetration of sexual aggression, including angry, aroused, powerful, and impulsive. Items were averaged to form a sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations scale (α = .93; M = 2.55; SD = .92).

Sexual aggression intentions

After rating their current emotional state, participants were prompted to rate their intentions to engage in sexual intercourse with Kim without a condom, despite her refusal to engage in unprotected sexual intercourse. Using a seven-point Likert scale (e.g. 1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely), participants estimated their likelihood of engaging in the following acts without a condom: genital contact, vaginal sex, oral sex, and anal sex. As is standard in this literature (Kolivas & Gross, 2007), these intention items assessed the likelihood of specific sexual behaviors without labeling them as “sexual aggression” or “rape”. The mean of these items was computed to form a sexual aggression intentions scale (α = .86; M = 3.09; SD = 1.75).

Post-incident labeling

To assess whether or not participants themselves would label these behaviors as sexually aggressive, after rating their behavioral intentions, participants were asked 3 items about how they would label the situation, such as If you were to have sex with Kim at this point, how likely would you be to consider it rape? Responses were rated on a seven-point Likert scale (e.g. 1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely). Items were averaged to form a post-incident labeling scale (α = .77; M = 4.77; SD = 1.86).

Post-incident concern

Participants then rated their perceptions of how they would feel following their interaction with Kim on 7 items, such as worried about the consequences of my actions, ashamed of myself, and regretful about my decisions. Responses were rated on a seven-point Likert scale (e.g. 1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely). The mean of these items was computed to form a post-incident concern scale (α = .77; M = 4.30; SD = 1.32).

Results

Overview of Data Analytic Strategy

First, correlations between measured variables were conducted to assess bivariate relationships. Second, to test for the hypothesized interaction between alcohol-aggression expectancies and alcohol intoxication on sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed. Based on these preliminary analyses, a path analysis model was tested to examine the theoretical model depicted in Figure 1.

Correlations

Bivariate correlations among the measured variables appear in Table 1. Point biserial correlations indicated that alcohol intoxication was significantly correlated with sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations, post-incident labeling, and post-incident concern, with intoxicated participants reporting greater sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations and lesser post-incident labeling and post-incident concern than did sober participants. Pearson product moment correlations revealed that sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations, sexual aggression intentions, post-incident labeling, and post-incident concern were all related to one another in the expected direction.

Table 1.

Point Biserial and Pearson Product Moment Bivariate Correlations between Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Alcohol Intoxication | -- | −.09 | .02 | .18* | .16 | −.40*** | −.30** |

| 2. | Alcohol-Aggression Expectancies | -- | .19* | .15 | .25** | −.11 | .00 | |

| 3. | Intoxication x Expectancies Interaction | -- | .31** | .22* | −.26** | −.17 | ||

| 4. | Sexual Aggression Congruent Emotion/Motivations | -- | .49*** | −.58*** | −.26** | |||

| 5. | Sexual Aggression Intentions | -- | −.70*** | −.40*** | ||||

| 6. | Post-incident Labeling | -- | .53*** | |||||

| 7. | Post-incident Concern | -- | ||||||

Note.

+ p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Point biserial correlations were computed for correlations involving one dichotomous variable and one continuous variable. Pearson Product Moment correlations were computed to describe the relationship between two continuous variables.

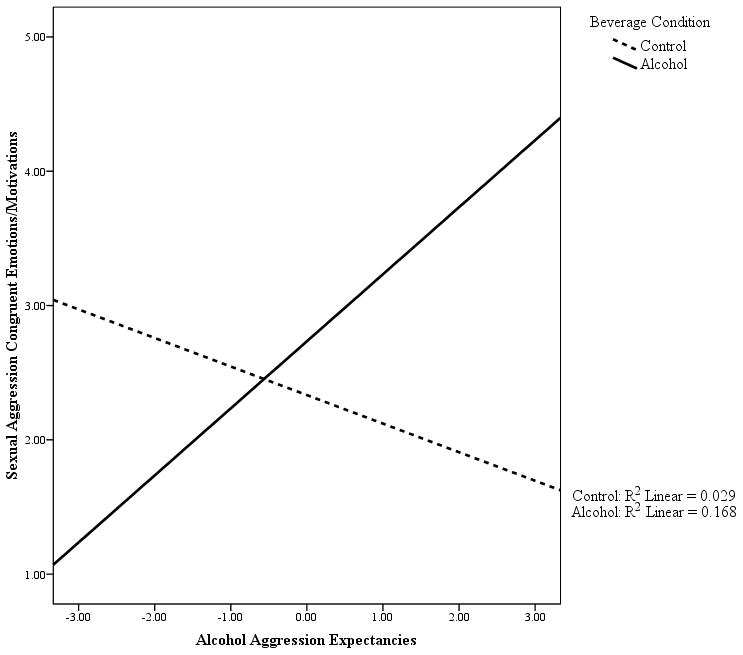

Hierarchical Multiple Regression

A hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to test for the main and interactive effects of alcohol intoxication and alcohol-aggression expectancies on participants’ sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations. The main effects of alcohol intoxication and alcohol-aggression expectancies (centered) were entered on the first step, while the interaction term for these two variables was entered on the second step. The first step of the regression equation was significant (R2 = .075, p < .05), with alcohol intoxication significantly predicting sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations in the expected direction (β = .23, p < .05). As predicted, this main effect was qualified by a significant two-way interaction of alcohol intoxication x alcohol-aggression expectancies (β = .28, p < .01) as entered on the second step (R2cha = .076, p < .01). As illustrated in Figure 2, intoxicated participants with stronger alcohol-aggression expectancies reported greater sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations relative to intoxicated participants with weaker alcohol-aggression expectancies. For sober participants, alcohol-aggression expectancies were not significantly related to sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations.

Figure 2.

Graphs of alcohol-aggression expectancies by intoxication interaction for sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations.

Model testing

Path analysis using Mplus statistical modeling software for Windows (version 4.0, Muthén & Muthén, 2004) with maximum likelihood estimation was used to test the theoretical model (Figure 1). Based on our hypotheses and the preliminary analyses, the following path model was tested: the outcome responses of post-incident labeling and post-incident concern were regressed on sexual aggression intentions, sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations, alcohol intoxication, and the two-way interaction of alcohol intoxication by alcohol-aggression expectancies. The correlation between post-incident labeling and post-incident concern was also estimated. Additionally, sexual aggression intentions were regressed on sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations, alcohol intoxication, and the two-way interaction of alcohol intoxication by alcohol-aggression expectancies, while sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations were regressed on alcohol intoxication and the interaction of alcohol intoxication by alcohol-aggression expectancies. Estimation of these effects allowed for assessing the effect of the two-way interaction in the presence of the lower level effect and replicating the two-way interaction effect found in the preliminary regression analysis.

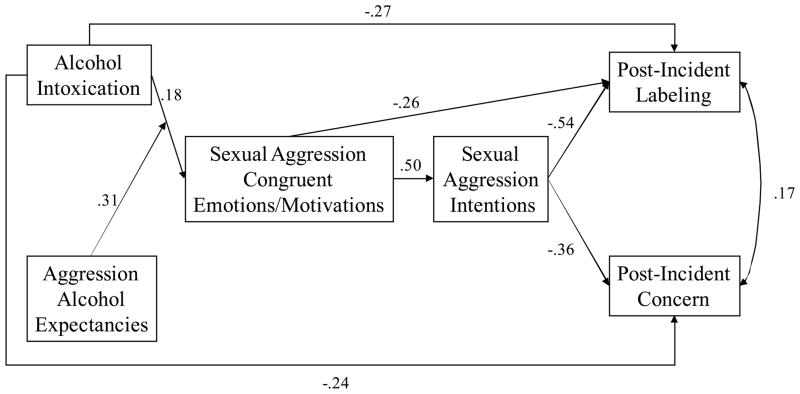

The hypothesized model fit the data well, χ2(5) = 8.619, p = .13, CFI = .982, TLI = .934, RMSEA = .076, SRMR = .046. The non-significant paths were fixed to zero in the final model (shown in Figure 3), which also fit the data well, χ2(9) = 10.723, p = .30, CFI = .991, TLI = .983, RMSEA = .039, SRMR = .055. Chi-square difference testing (Satorra & Bentler, 2001) comparing the hypothesized model to the final model indicated that the final model fit the data as well as the hypothesized model, Δχ2(4) = 2.104, p = ns. All of the paths that were free to vary in the final model remained significant. The model accounted for 13% of the variance in sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations, 25% of the variance in sexual aggression intentions, 62% of the variance in post-incident labeling, and 21% of the variance in post-incident concern.

Figure 3.

Final model with standardized estimates. All paths in the figure are significantly different from zero (p < .05).

Following procedures outlined by Bryan, Schmiege, & Broaddus (2007), a series of indirect effects tests were examined. The indirect effects of the two-way interaction of alcohol intoxication by alcohol-aggression expectancies on sexual aggression intentions working through sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations were tested. The indirect effects of this interaction on post-incident labeling and post-incident concern through sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations and sexual aggression intentions were also tested separately. The indirect effects of the two-way interaction on sexual aggression intentions (z = 3.11, p < .05), post-incident labeling (z = −3.20, p < .05), and post-incident concern (z = −2.54, p < .05) were all significant. Briefly, the intoxication by expectancy interaction significantly increased sexual aggression intentions through its increase of sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations. This interaction also indirectly, but significantly, decreased participants’ post-incident labeling and post-incident concern through its effects on sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations and sexual aggression intentions.

Discussion

In support of the hypotheses, results from this research indicate that alcohol intoxication in conjunction with aggression-related alcohol expectancies indirectly increases men’s intentions to proceed with unprotected sexual intercourse with an unwilling partner through an increase in emotions and motivations congruent with sexually aggressive behavior. Men’s perceptions of the incident afterwards were also directly and indirectly influenced by alcohol intoxication and alcohol expectancies. Because the situation described in this study involved proceeding with unprotected sexual intercourse despite the woman’s clear indications that she did not want to have unprotected sex, these findings highlight some of the ways in which alcohol may relate to increased sexual infection transmission at an event-level through an increased likelihood of unwanted unprotected sex (Davis et al., 2008; Peterson et al., 2009).

In support of the hypothesized model, alcohol intoxication did indeed increase sexual aggression intentions in an unprotected sexual situation with a casual sex partner through its effects on participants’ in-the-moment self-reported emotions involving feelings of arousal, anger, impulsivity, and power. Moreover, this effect was moderated by men’s expectations that alcohol would increase their aggressive behavior. Intoxicated men with stronger beliefs that alcohol increases their aggression reported the greatest sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations, which then predicted greater unprotected sexual aggression intentions. This finding supports the hypothesis that intoxication and alcohol expectancies are relevant mechanisms underlying the alcohol-sexual aggression connection. As noted in previous work (e.g. Davis et al., 2007; Morris & Albery, 2001; Moss & Albery, 2009), the confluence of intoxication with an expectation that intoxication leads to a particular behavioral response may increase the likelihood of that particular response more than either alcohol or expectancies alone. Further, these results underscore the value of investigating the effects of this intoxication-expectation synergy on potential mediators of the alcohol-behavior link, such as emotions.

In concurrence with research highlighting the role of emotional and visceral influences on decision making (e.g. Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001), our findings support the continued examination of the role of in-the-moment emotions, as well as cognitions, in sexual decision-making processes. In this study, participants’ self-reported emotions during the situation directly increased their sexual aggression intentions and also decreased their labeling of such actions as “rape”. Although much work previous work has focused on the role of alcohol-induced cognitive impairment as a possible mechanism underlying the effects of alcohol on risky and aggressive sexual behavior, the current results highlight the importance of including emotional and motivational processes in these examinations as well. Indeed, Ditto et al. (Ditto, Pizarro, Epstein, Jacobson, & MacDonald, 2006) have referred to a form of “motivational myopia” that may occur when certain visceral states, such as sexual arousal, are activated. Thus, intoxicated individuals in particular emotional states may in effect be hit with a “double-whammy” such that their alcohol-induced cognitive impairment coupled with their emotionally-induced short-sightedness results in a greater focus on obtaining a salient desired object, perhaps through whatever behavioral means necessary (Ditto et al., 2006). Consequently, future work in this area would be well-served to consider the interplay between alcohol, cognitions, and emotions and other motivators in these processes. Although the current study lacked the statistical power to test the relative effects of the different emotional and motivational mediators underlying the alcohol-sexual aggression relationship, future research could explore these relative effects as well as the ways in which more dispositional measures, such as trait aggressivity (Giancola, Godlaski, & Parrott, 2005) or pre-existing hostility (Abbey et al., 2009), influence these state-specific motivators.

In addition to these moderated-mediation effects of alcohol on sexual aggression intentions, alcohol intoxication both directly and indirectly decreased men’s labeling of sexual aggression as “rape” and also decreased their concern about their actions after the incident. Consistent with prior research (e.g. Norris et al., 2002), alcohol ingestion may result in a myopic attentional focus on instigatory pleasure cues rather than inhibitory aggressive cues, with intoxicated men paying greater attention to cues that may indicate a woman’s sexual willingness (e.g. preceding consensual sexual activity) than to cues that indicate her sexual unwillingness (e.g. verbal refusal to have unprotected sex). This, coupled with the finding that sexual aggression congruent emotions/motivations directly predicted decreased rape labeling, may help explain why such a large portion of the variance in rape labeling was accounted for in this model and is congruent with prior research indicating that alcohol intoxication, emotions, and other motivators are consistently used by sexual aggressors to diminish, excuse, or justify their actions (Mann & Hollin, 2007; Scully & Marolla, 1984). Because these findings suggest that sexually aggressive acts committed during states of intoxication are more likely to be viewed as consensual by the perpetrator and result in less distress on his part after the incident, intervention efforts with perpetrators who have committed sexual assault while intoxicated may need to focus their initial efforts on education regarding alcohol’s effects on perceptions of sexual assault situations.

These results also highlight the importance of including information in sexual aggression prevention work about the ways in which alcohol intoxication and alcohol expectancies may influence both cognitive and emotional processes such that the likelihood of sexually aggressive behavior is increased. Importantly though, such prevention messages may ultimately strengthen individuals’ beliefs about alcohol’s influence on sexually aggressive behavior, thereby paradoxically increasing such behavior when drinking (Dermen, Cooper, & Agocha, 1998). Because of this potential, it is critical that prevention efforts seek ways to educate their participants about the alcohol-aggression connection without inadvertently increasing their sexual aggression likelihood through strengthened alcohol expectancies.

Limitations

Future research could address some of the limitations of this research. First, because only one alcohol dosage was used, we cannot extend these findings to situations that involve different amounts of alcohol consumption. Because many sexual assault incidents likely involve higher levels of intoxication than that used in the current study, future work in this area should consider utilizing higher alcohol doses (e.g. target peak BAL of.10%). A placebo condition was not included in the design; thus, potential dosage set effects cannot be determined through this study and should be examined in future research. Similarly, the sample was limited to moderate social drinkers who also engage in heavy episodic drinking; lighter drinkers and problem drinkers, excluded due to ethical concerns, may have responded differently to the experimental paradigm. That noted, the heavy episodic drinkers included in this study are the most at-risk for engaging in these aggressive behaviors and are thus the most relevant group to investigate (Parrot & Giancola, 2006). As with other experimental research regarding sexual decision making, the use of hypothetical scenarios has both costs and benefits. While the use of such a scenario allows for the control of numerous variables, it likely does not capture all relevant variables pertinent to making such decisions. Also, because only one type of relationship was presented in the scenario – a casual sexual relationship – this pattern of findings may not apply to other relationship types. Finally, although behavioral intentions may not always predict actual behavior, research indicates that men’s estimations of their sexual aggression likelihood do indeed correspond with their real-world sexually aggressive behavior (Malamuth, 1984).

Conclusion

This risk constellation of alcohol, sexual aggression, and unprotected sex highlights the importance of including and targeting young heterosexual men in prevention programs. Although termed the “forgotten group” regarding STI prevention (Exner, Gardos, Seal, & Ehrhardt, 1999), some have argued that interventions with heterosexual men, particularly those who are violent towards women, may be the key to controlling the spread of the STI and HIV epidemics (Elwy, Hart, Hawkes, & Petticrew, 2002; Maman, Campbell, Sweat, & Gielen, 2000). The current results underscore this notion by illustrating the pathways through which alcohol intoxication and expectancies may influence young men’s use of sexual aggression to obtain unprotected sex with an unwilling partner. As the empirical support illustrating the linkages among alcohol use, violence, and sexual risk continues to grow, it is evident that prevention programs in both the sexual violence and sexual risk domains must address the intersection of these risk factors in their efforts.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants to the author from the Alcoholic Beverage Medical Research Foundation and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01-AA017608). Portions of this paper were presented at the 2009 annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism. Correspondence concerning this paper should be sent to Kelly Davis, University of Washington, School of Social Work, Box 354900, Seattle, Washington 98195. E-mail may be sent to kcue@u.washington.edu.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/PHA

References

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Ross LT, Zawacki T. Alcohol expectancies regarding sex, aggression, and sexual vulnerability: Reliability and validity assessment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13(3):174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, BeShears R, Clinton-Sherrod AM, Zawacki T. Cross-sectional predictors of sexual assault perpetration in a community sample of single African American and Caucasian men. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:54–67. doi: 10.1002/ab.20107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Saenz C. Alcohol’s role in men’s use of coercion to obtain unprotected sex. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:1329–1348. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Saenz C, Buck PO. The cumulative effects of acute alcohol consumption, individual differences and situational perceptions on sexual decision making. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005b;66(1):82–90. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H. Love, sex, and power: Considering women's realities in HIV prevention. American Psychologist. 1995;50:437–447. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariely D, Loewenstein G. The heat of the moment: The effect of sexual arousal on sexual decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2006;19:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: Estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara G, Cinanni V, D’Imperio G, Passerini S, Renzi P, Travaglia G. Indicators of impulsive aggression: Present status of research on irritability and emotional susceptibility scales. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:665–674. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Trends in reportable sexually transmitted diseases in the United States, 2007: National surveillance data for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. 2009 Retrieved February 8, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats07/trends.htm.

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol (Supplement) 2002;(14):101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, George WH, Norris J. Women's responses to unwanted sexual advances: The role of alcohol and inhibition conflict. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28 (4):333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Hendershot CS, George WH, Norris J, Heiman JR. Alcohol's effects on sexual decision making: An integration of alcohol myopia and individual differences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2007;68:843–851. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Norris J, George WH, Martell J, Heiman JR. Men's likelihood of sexual aggression: The influence of alcohol, sexual arousal, and violent pornography. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32(6):581–589. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Schraufnagel TJ, George WH, Norris J. The use of alcohol and condoms during sexual assault. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2008;2:281–290. doi: 10.1177/1557988308320008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermen KH, Cooper ML. Sex-related alcohol expectancies among adolescents: II. Prediction of drinking in social and sexual situations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Dermen KH, Cooper ML, Agocha VB. Sex-related alcohol expectancies as moderators of the relationship between alcohol use and risky sex in adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:71–77. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditto PH, Pizarro DA, Epstein EB, Jacobson JA, MacDonald TK. Visceral influences on risk-taking behavior. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2006;19:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Marsh DM, Moeller FG, Chokshi RV, Rosen VC. Effects of moderate and high doses of alcohol on attention, impulsivity, discriminability, and response bias in immediate and delayed memory task performance. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1702–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwy AR, Hart GJ, Hawkes S, Petticrew M. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus in heterosexual men: A systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:1818–1830. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner TM, Gardos PS, Seal DW, Ehrhardt AA. HIV sexual risk reduction interventions with heterosexual men: The forgotten group. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3:347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D' Amico EJ, Katz EC. Intoxicated sexual risk taking: An expectancy or cognitive impairment explanation? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(1):54–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Davis KC, Norris J, Heiman JR, Stoner SA, Schacht RL, Hendershot CS, Kajumulo KF. Indirect effects of acute alcohol intoxication on sexual risk-taking: The roles of subjective and physiological sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:498–513. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2000;11:92–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Zeichner A. The biphasic effects of alcohol on human physical aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(4):598–607. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlaski AJ, Giancola PR. Executive functioning, irritability, and alcohol-related aggression. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:391–403. doi: 10.1037/a0016582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CM, Carey MP, Carey KB. Effects of a drinking event on behavioral skills and condom attitudes in men: Implications for HIV risk from a controlled experiment. Health Psychology. 1997;16(5):490–495. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross AM, Bennett T, Sloan L, Marx BP, Juergens J. The impact of alcohol and alcohol expectancies on male perception of female sexual arousal in a date rape analog. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9(4):380–388. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, Noel NE, Sutter Hernandez J. Alcohol and male acceptance of sexual aggression: The role of perceptual ambiguity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30(6):1186–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Cherry C, Jooste S, et al. Gender attitudes, sexual violence, and HIV/AIDS risks among men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(4):299–305. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolivas ED, Gross AM. Assessing sexual aggression: Addressing the gap between rape victimization and perpetration prevalence rates. Aggression and Violence Behavior. 2007;12:315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP. Hidden rape: Incidence, prevalence, and descriptive characteristics of sexual aggression in a national sample of college students. In: Burgess AW, editor. Sexual assault. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Garland; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsky L. Epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. American Journal of Medicine. 1997;102(5A):3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie J, Earleywine M, Schiffman J, Pedersen E, Marriot C. Effects of alcohol, expectancies, and partner type on condom use in college males: Event-level analyses. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(3):259–266. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G, Nagin D, Paternoster R. The effect of sexual arousal on expectations of sexual forcefulness. Journal of Research in Crime & Delinquency. 1997;32:443–473. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:267–286. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAndrew C, Edgerton RB. Drunken comportment: A social explanation. Oxford, England: Aldine; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Martineau AM. Alcohol myopia and condom use: Can alcohol intoxication be associated with more prudent behavior? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78(4):605–619. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, MacDonald G, Zanna MP, Fong G. Alcohol, sexual arousal, and intentions to use condoms in young men: Applying alcohol myopia theory to risky sexual behavior. Health Psychology. 2000;19(3):290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Why common sense goes out the window: Effects of alcohol on intentions to use condoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22(8):763–775. [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Schum JL, Lynch KG. The relationship between alcohol and individual differences variables on attitudes and behavioral skills relevant to sexual health among heterosexual young adult men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33(6):571–584. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044741.09127.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM. Aggression against women: Cultural and individual causes. In: Malamuth NM, Donnerstein E, editors. Pornography and Sexual Aggression. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat MD, Gielen AC. The intersections of HIV and violence: Directions for future research and interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:459–478. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE, Hollin CR. Sexual offenders’ explanations for their offending. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2007;13:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Gross AM, Adams HE. The effect of alcohol on the responses of sexually coercive and noncoercive men to an experimental rape analogue. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research & Treatment. 1999;11(2):131–145. doi: 10.1177/107906329901100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Gross AM, Juergens JP. The effects of alcohol consumption and expectancies in an experimental date rape analogue. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment. 1997;19(4):281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Sayette MA. Experimental design in alcohol administration research: Limitations and alternatives in the manipulation of dosage-set. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54(6):750–761. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AB, Albery IP. Alcohol consumption and HIV risk behaviors: Integrating the theories of alcohol myopia and outcome expectancies. Addiction Research & Theory. 2001;9:73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Moss AC, Albery IP. A dual-process model of the alcohol-behavior link for social drinking. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:516–530. doi: 10.1037/a0015991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Users Guide. 4. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors CJ, O'Leary A. Responses of male inmates to primary partner requests for condom use: Effects of message content and domestic violence history. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2003;15(1):93–108. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.93.23841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors CJ, O'Leary A, Labouvie E. Domestically violent and nonviolent male inmates' responses to their partners' requests for condom use: Testing a social-information processing model. Health Psychology. 1999;18(4):427–431. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Davis KC, George WH, Martell J, Heiman JR. Alcohol's direct and indirect effects on men's self-reported sexual aggression likelihood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:688–695. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, George WH, Davis KC, Martell J, Leonesio RJ. Alcohol and hypermasculinity as determinants of men's empathic responses to violent pornography. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:683–700. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Kerr KL. Alcohol and violent pornography: Responses to permissive and nonpermissive cues. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Suppl. 1993;11:118–127. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Martell J, George WH. Men’s judgments of a sexual assailant in an eroticized rape: The role of rape myth attitudes and contextual factors. In: Martinez M, editor. Prevention and Control of Aggression and the Impact on Its Victims. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Otto-Salaj LL, Traxel N, Brondino MJ, Reed B, Gore-Felton C, Kelly JA, et al. Reactions of heterosexual African American men to women’s condom negotiation strategies. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46 doi: 10.1080/00224490903216763. first published on: 16 September 2009 (iFirst) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrot DJ, Giancola PR. The effect of past-year heavy drinking on alcohol-related aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:122–130. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson ZD, Janssen E, Heiman JR. The association between sexual aggression and HIV risk behavior in heterosexual men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;25:538–556. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny AD, Miller BA, Kaplan HB. The brief MAST: A shortened version of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1972;129:342–345. doi: 10.1176/ajp.129.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Santana C, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1873–1878. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rule BG, Nesdale AR. Emotional arousal and aggressive behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1976;83:851–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacht RL, Stoner SA, George WH, Norris J. Idiographically-determined versus standard absorption periods in alcohol administration studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:925–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully D, Marolla J. Convicted rapists’ vocabulary of motive: Excuses and justifications. Social Problems. 1984;31:530–544. [Google Scholar]

- Scully D, Marolla J. Riding the bull at Gilley’s: Convicted rapists describe the rewards of rape. Social Problems. 1985;32:251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45(8):921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M. The impact of men's alcohol consumption on perpetration of sexual aggression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22(8):1239–1263. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Fillmore MT, Norris J, Abbey A, Curtin JJ, Leonard KE, et al. Understanding alcohol expectancy effects: Revisiting the placebo condition. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(2):339–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the national violence against women survey. (No. 210346) Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki T, Abbey A, Buck PO, Mcauslan P, Clinton-Sherrod AM. Perpetrators of alcohol-involved sexual assaults: How do they differ from other sexual assault perpetrators and nonperpetrators? Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29:366–380. doi: 10.1002/ab.10076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]