Abstract

Purpose: Breathing motion can create large errors when performing magnetic resonance (MR) thermometry of the breast. Breath holds can be used to minimize these errors, but not eliminate them. Between breath holds, the referenceless method can be used to further reduce errors by relying on regions of nonheated fatty tissue surrounding the heated region. When the surrounding tissue is heated (i.e., for a hyperthermia treatment), errors can result due to phase changes of the small amounts of water in the tissue. Therefore, an extension of the referenceless method is proposed which fits for the field in fatty tissue independent of temperature change and extrapolates it to the water-rich regions.

Methods: Nonheating experiments were performed with male volunteers performing breath holds on top of a phantom mimicking a breast with a tumor. Heating experiments were also conducted with the same phantom while mechanically simulated breath holds were performed. A nonheating experiment was also performed with a healthy female breast. For each experiment, a nonlinear fitting algorithm was used to fit for temperature change and B0 field inside of the fatty tissue. The field changes were then extrapolated into water-rich (tumor) portions of the image using a least-squares fit to a fifth-order equation, to correct for field changes due to breath hold changes. Similar results were calculated using the image phase, to mimic the use of the referenceless method.

Results: Phantom results showed large reduction of mean error and standard deviation. In the non-heating experiments, the traditional referenceless method and our extended method both corrected by similar amounts. However, in the heating experiments, the average deviation of the temperature calculated with the extended method from a fiber optic probe temperature was approximately 50% less than the deviation with the referenceless method. The in vivo breast results demonstrated reduced standard deviation and mean.

Conclusions: In this paper, we have developed an extension of the referenceless method to correct for breathing errors using multiecho fitting methods to fit for the B0 field in the fatty tissue and using measured field changes as references to extrapolate field corrections into a water-only (tumor) region. This technique has been validated in a number of situations, and in all cases, the correction method has been shown to greatly reduce temperature error in water-rich regions. The method has also been shown to be an improvement over similar methods that use image phase changes instead of field changes, particularly when temperature changes are induced.

Keywords: magnetic resonance thermometry, breast cancer

INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies have shown that the combination of radiation therapy and hyperthermia, when delivered at moderate temperatures (40°–45 °C) for sustained times (30–90 min), can help to provide palliative relief and augment tumor response, local control, and survival.1, 2, 3 In trials where temperatures were measured invasively during treatment, retrospective analysis has shown that the temperatures achieved were significantly correlated with beneficial outcome.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 The dependence of treatment success on achieved temperature suggests that an accurate method to measure the delivered thermal dose is needed.

A number of research groups have demonstrated that magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is effective and accurate for noninvasively assessing temperature changes in tissues associated with absorption of nonionizing radiation.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 The most common MR imaging method used to measure temperature changes is the proton resonant frequency shift (PRFS) method. For this method, a change in temperature results in a change in MR frequency (and thus image phase) for water protons, allowing temperature changes to be measured. This is accomplished by acquiring MR phase images at two points in time and using the phase difference between the images to calculate temperature change at each pixel.

The PRFS method has a number of limitations when trying to perform MR thermometry of hyperthermia for the treatment of breast cancer. One limitation is the B0 field changes that can occur due to the motion of nearby tissue, even in the case that the imaged tissue does not move. The B0 field around the chest usually has small distortions due to the magnetic susceptibility difference between the tissue and the air in the lungs and the bore of the magnet. As the shape of the chest changes due to respiration, the B0 distortion will change correspondingly. These field changes then result in phase changes in the images, which in turn result in temperature error when using PRFS thermometry methods. The effects on the B0 field due to breathing have been measured by several groups in the brain,16, 17, 18 breast,19, 20, 21 and abdomen.22 The effects have also been simulated by several groups.23, 24, 25 In the breast, a range of field changes near the chest wall from 0.14 to 0.40 ppm is seen between expiration and inspiration. At all field strengths, these changes would equate to erroneous temperature changes of approximately 14 and 40 °C. A simple correction for this phenomenon would be to acquire all PRFS images during subsequent 10–20 s breath hold by the subject. However, each breath hold is typically not reproducible,26, 27 and thus while breath holds serve to reduce the B0 changes compared to free breathing, they do not eliminate them.

The fatty tissues of the breast can be another complication since the phase changes in tissues that contain fat and water depend on the fat∕water ratio due to the fact that the fat has negligible phase change with temperature.28 However, the fat in breast tissue affords an opportunity to use the fat as a reference tissue. The “referenceless method,” which has been used in previous ablation studies to extrapolate the phase of surrounding regions into the ablated region29, 30, 31 has been used to correct for local B0 changes. This works well since the surrounding regions are not heated and thus provide a reference for B0. However, in hyperthermia treatments with RF applicators, the heated region can be widespread, with several degrees of temperature change in surrounding regions. Since fatty tissue in breast often contains water (5%–20%), PRFS phase changes will occur in the fat during heating, producing errors in the phase correction of the referenceless method.

In this work, we propose an extension of the referenceless method for the situation in which large regions are heated. We acquire multiecho data and fit a signal model to separate out the fat and water components. We then obtain the B0 field changes and temperature changes separately in the fatty tissue. The measured B0 field accounts for all nontemperature related changes (breathing, field drift, etc.). These measured field changes are subsequently used as references to extrapolate phase corrections into a water-only (tumor) region. Phantom studies were performed to validate the method, in which a phantom was imaged while the B0 field was changed to simulate respiration and breath holds and the accuracy of the proposed correction method was evaluated by comparing MR estimated temperature change to those measured with fiber optic thermal probes. The results were compared to the simple application of the referenceless method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Field and temperature fitting model

Triple echo data were acquired during each experiment and were analyzed with a nonlinear fitting algorithm that fits for temperature change and B0 field (NLM-Temp, previously used in Ref. 32). The nonlinear algorithm was used to prevent B0 field measurement bias that occur when using linear least-squares estimation algorithms33 (such as IDEAL). The water and fat signal model for the fitting algorithm contained three fat peaks such that the MR signal from a voxel containing both water and fat would be

| (1) |

where Aw and Af are the TE=0 (complex valued) amplitudes at the TR of interest for water and fat respectively. and are the T2* values for water and fat, respectively, α is the PRFS thermal coefficient (−0.01 ppm∕°C), f is the imaging frequency at 1.5 T (63.87 MHz), φfw are the frequency differences between the fat peaks and the water peak at a “baseline” temperature Tb, ψ is the offset from the imaging frequency (excluding offsets due to temperature change), and ε is Gaussian noise with mean=0 and . β is the relative ratio of the area of each fat peak compared to the area of all fat peaks combined, with all values adding up to 1. The variable n is the echo number, for which there are total of three for the present experiments. The set of echoes described by s(n) is referred to as an echo sampling group (ESG). Finally, ΔT is the temperature change from the baseline temperature at which the fat-water frequency differences φfw would be measured.

The fitting algorithm was programmed in C and assumes that all parameters are known except for ΔT and B0. All other parameters were found through a phantom characterization.

Fitting the temperature-independent field changes

Initial B0 field values were calculated for each experimental time point using MP-IDEAL.36 For each time point after the first, the B0 values at the previous time point were used as the initial starting value for the MP-IDEAL algorithm to prevent field wrapping. The results of the MP-IDEAL method were used to determine the pixels in the area of interest (the phantom or the in vivo breast∕chest wall) that have a fat∕water signal ratio that is greater than 50%. This was done to ensure that all of the pixels used have sufficient signal to calculate an accurate B0 field measurement. The calculated B0 values from MP-IDEAL in the selected pixels were used in the NLM-Temp algorithm as the initial guess for the field value at each pixel. The initial temperature guess for each pixel was assumed to be 0 °C. For the in vivo breast data, a region growing algorithm was used with the MP-IDEAL algorithm to ensure smoothly varying B0 maps. Field maps were calculated for several initial field starting values ranging from −200 to +200 Hz by 20 Hz increments. The algorithm used a spiral trajectory from a central pixel in the breast. For the first time point, the starting field value for the central pixel was chosen to be the value with the least residue. For the subsequent pixels on the trajectory, the mean of the surrounding field values was calculated and the closest field value from the predetermined solutions was found to enforce field smoothness.

Field extrapolation

The differences between the field values fit with NLM-Temp at consecutive time points were then interpolated to the spatial points that fell below the 50% threshold by using them as input into a least-squares fitting algorithm to fit the field differences and interpolate them into the water-rich regions. The least-squares algorithm assumes a fifth order equation for the phantom experiments and a third order equation for the in vivo breast experiment since it was more stable. Based on the noise seen in the experiments with no temperature change present, the order with the lowest noise and mean closest to 0 °C was chosen by analyzing the noise of the signal after correction with orders ranging from 1 to 6. Once these value coefficients of the model were solved for, the values were then input into Eq. 2 to solve for the B0 field change for all pixels of the image. The fitting of the measured B0 field is referred to as the least-squares single pixel (LSSP) algorithm.

The LSSP algorithm results in field change maps that predict the amount of field changes that occurred independent of temperature change between time points. These field change maps were then converted to phase change maps at the first echo of the ESG by multiplying the field map by the first TE value (15.4 ms in all experiments). The predicted phase change maps were subtracted from the phase change maps calculated from the changes in phase between time points at the 1st echo time. This resulted in corrected phase change maps that were converted to temperature maps using Eq. 2,34

| (2) |

where f=63.87 MHz, TE=15.4 ms, and α=−0.01 ppm∕°C.

Additional calculations were performed to compare the proposed method of correction using temperature independent field maps with the referenceless thermometry method mentioned in the introduction. The simple referenceless thermometry method was implemented by using the image phase change maps of the fatty tissue (which can have erroneous values due to combined heating related PRFS and B0 changes) instead of the field change maps as input into the LSSP method. However, differences in phase were used instead of phase from a single time point (the typical way the referenceless method is performed) due to the temperature change in the referenced regions. The same pixels used with the field change maps were used with the phase change maps. The phase changes at the first echo time (TE=15.4 ms) were used to avoid phase wrap problems.

Phantom design and construction

Phantoms mimicking a large breast with a tumor were constructed using the recipe used by Wyatt et al.35 Phantoms consisted of a 10.80 cm×14.92 cm circular container filled with 85:15 fat-water gelatin. A 5.08 cm diameter cylinder was placed through the center of each phantom filled with 100% water gelatin to mimic a tumor. Four #19 catheters were inserted through the phantoms, three placed around the tumor and the fourth catheter placed in the center of the tumor cylinder to allow temperature measurement with inserted thermal probes. A schematic showing the construction and materials of the phantoms is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Construction of phantom mimicking a large breast with breast cancer. (b) Magnitude image of the phantom in the applicator and the air and water bags on top for the first phantom heating experiment.

Fat-water phantom characterization

To characterize the known parameters, nine ESGs (listed in Table 1) were acquired in approximately the same slice used for all phantom experiments. First, the complex image intensity of the nine ESGs were fitted with the MP-IDEAL algorithm36 (since it does not require initialization). The relative amplitudes of the three fat peaks (β1, β2, and β3) were determined using the self-referenced method described by Yu et al.,36 with one peak at −222 Hz, one at −175 Hz, and the other at 33 Hz. Finally, the magnitudes of the water and fat signals from MP-IDEAL were fitted for Aw, Af, , and . It should be noted that nine ESGs would not be necessary in a clinical situation, with that number being used for increased accuracy with the phantoms. For the breast experiment, the T2* values measured in the phantom were used since they were in the range of human fatty tissue. The measured water and fat intensity values from the MP-IDEAL fit (approximately equal to and ) were used to extrapolate the approximate Aw and Af values by multiplying them by the inverse of the T2* decay.

Table 1.

TE values for the ESGs used for water and fat fitting with MP-IDEAL. All times are in ms.

| TE1 | TE2 | TE3 |

|---|---|---|

| 6.3 | 7.8 | 9.3 |

| 11.1 | 12.6 | 14.1 |

| 15.1 | 16.6 | 17.1 |

| 15.9 | 17.4 | 18.9 |

| 17.4 | 18.9 | 20.4 |

| 19.5 | 21.0 | 22.5 |

| 20.7 | 22.2 | 23.7 |

| 24.2 | 25.7 | 27.2 |

| 28.7 | 30.2 | 31.7 |

Phantom nonheating experiment with volunteer breath holds

Nonheating experiments were performed to evaluate the effectiveness of correcting for phase variations due to breathing. A version of the phantom (without catheters) was placed inside the hyperthermia applicator surrounded by a water bolus that is part of the applicator and taped down across the surface of the patient support. Once the phantom was secured, the bolus was filled until it surrounded the phantom. The water bolus of the applicator was filled with 99.8% pure D2O (Sigma Aldrich #617385, St. Louis, MO, USA) to provide heating RF coupling and was used in this experiment to mimic the typical heating configuration even though the phantom was unheated. The patient breast support consisted of a heat-formed plastic cup with a hole on one side to allow a breast to extend into the applicator. A picture of the phantom secured inside the applicator is shown in Fig. 2. A thin foam pad was then placed over the top of the phantom to prevent it from causing discomfort for the volunteer. The volunteer was then placed on top of the applicator so that their right chest area was situated on top of the phantom. Experiments were performed with two male volunteers recruited through an IRB approved nonheating protocol. One experiment was performed with volunteer #1, where the volunteer was instructed to breath hold at full-inspiration. Two experiments were performed with volunteer #2, one experiment with breath holds on full-inspiration and the other with breath holds on end expiration. During each breath hold, a 5 mm thick slice near the center of the phantom was imaged on a 1.5 T GE Signa HDX (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with a multigradient echo pulse sequence and TE=[15.4,21.8,28.2 ms], TR=50 ms, flip angle=30°, 128×128, FOV=28 cm, BW=15.63 kHz, and NEX=2.0. The multigradient echo sequence had the same gradient direction for all TE values to ensure that gradient polarity differences did not cause additional phase shifts. TE values were chosen to have separation between water and fat of approximately 150°, 300°, and 450°, which has been found in previous experiments and simulations to provide low temperature noise.32 Imaging was performed with two local MR imaging coils located on the sides of the applicator. The scan time and breath hold duration was 16 s. Volunteer #1 was scanned for 10 breath holds, while volunteer #2 was scanned for 20 breath holds at full-inspiration and 12 breath holds at end-expiration. The experiments are referred to as experiments #1, #2, and #3, respectively.

Figure 2.

Picture of phantom secured inside the breast applicator. Tape was used to secure the phantom inside the applicator and prevent its movement with the volunteer’s breathing.

Phantom heating experiment with simulated breath holds

In order to avoid exposing volunteers to heating from the breast hyperthermia applicator, two heating experiments were performed using simulated breath holding provided by a setup described below. Three fiber optic temperature probes (Lumasense Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were placed into the catheters of the phantom so that the probes were within approximately 0.5 cm of its center. The phantom was placed into the same applicator and taped into the same position as used in the nonheating experiment. Once secured, the water bolus was filled with D2O until it surrounded the phantom. A large bag made of thin polyvinyl chloride (PVC) fabric filled with air was centered on top of the phantom. On top of the air bag another PVC bag was placed that was filled with de-ionized (DI) water. The air bolus was connected to a pump through a long Tygon tube running through the wall of the MR suite. A picture of the experimental setup can be seen in Fig. 3. The center of the phantom was imaged with one slice using the multigradient echo sequence used in the nonheating experiments.

Figure 3.

Experimental setup of the phantom in the applicator, the air bag, and the water bag. Tape was used to secure the phantom inside the applicator and prevent its movement during movement of the water bolus

Several images were acquired without intervention. For subsequent time points, the air bolus was either deflated or inflated using the pump, which in turn adjusted the height of the water bolus above the phantom. This was done to induce field changes similar to those that occur between breath holds where now the water bag substituted for the subject’s field distortion changes due to breathing. Between each inflation∕deflation, an image was acquired for MR thermometry. This setup provides simulation of MR thermometry between breath holds, with the inflation∕deflation of the air bolus referred to as a simulated breath hold. Once several simulated breath holds were performed, power was applied to the heating antennas. Approximately every 10 min, a simulated breath hold was performed and an image acquired. This was done until a large temperature change was observed in the fiber optic probes (approximately 7–8 °C). After successful heating, the heating antennas were turned off, and several more simulated breath holds were performed during the cool down period.

In vivo breast nonheating experiment

An in vivo nonheating experiment was performed to determine how well the field correction method works in a human female breast with real breath holds. A healthy female volunteer (age of 25) was enrolled under an IRB approved nonheating protocol. In this case, the glandular tissue was assumed to be similar to the tumor of a patient with breast cancer. The volunteer was positioned on the breast applicator support system so that their right breast was positioned inside the breast cup, which was filled with DI water to simulate the situation required for heating. First, axial and sagittal T1-weighted images of the entire breast were acquired. Based on these images, one 5 mm thick slice of the breast with a thick fat layer surrounding a modest amount of glandular tissue was chosen. An image of this slice was acquired during breath holds with the multigradient echo sequence used in the nonheating experiments. Breath holds were performed on end expiration for the duration of each scan, for a total of 11 breath holds.

RESULTS

Phantom nonheating experiment with volunteer breath holds

The values from the MP-IDEAL fit and the input into the NLM-Temp algorithm were Aw=552+∕−23.1, Af=6000+∕−119.3, , and . The normalized areas of the fat peaks were 0.773+∕−0.021 for the −222 Hz peak, 0.149+∕−0.014 for the −175 Hz peak, and 0.078+∕−0.016 for the +33 Hz peak.

A MR image of the phantom inside the applicator with the volunteer on top is shown in Fig. 4 with an overlay of a field change map measured with the NLM-Temp algorithm between breath holds. Due to the left∕right orientation of the phase encoding, significant motion artifacts from the heart prevent accurate imaging of the volunteer’s chest. Figure 5 shows the uncorrected and corrected temperature error images at the end of the first volunteer experiment.

Figure 4.

Overlay of a typical field change map (between two breath holds) on the magnitude image of the phantom in the applicator. The colorbar is in units of Hz. Notice the complex shape of the field changes and the severity of the changes near the top of the phantom.

Figure 5.

(a) Uncorrected and (b) corrected temperature errors between the first and the last breath hold of the nonheating phantom experiment with volunteer #1. Notice the increased uniformity inside the simulated tumor in the corrected image compared to the uncorrected image.

A plot showing the uncorrected PRFS temperature in the water gelatin and the temperature after correction with measured field changes fit using the LSSP method is shown in Fig. 6 for all nonheating phantom experiments. The mean and standard deviation of the uncorrected and corrected data sets for each experiment are shown in Table 2. Corrected data sets shown include the correction with field changes and correction with image phase changes (the simple referenceless method).

Figure 6.

Uncorrected and corrected temperature change measurements in the water gelatin (simulated tumor) for experiments (a) #1, (b) #2, and (c) #3 of the nonheating phantom experiments. The values are referenced to the temperature image at the first breath hold. Since no heating was applied, the temperature change should be 0 °C across all breath holds. This is seen in the corrected measurements, while the uncorrected measurements have large temperature error. Also, note the smaller error bars for the corrected measurements. This suggests that the correction method corrects for the spatial inhomogeneities induced by the breath hold field changes.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of phase changes (expressed as equivalent temperature change in °C) over all the time points in each nonheating experiment for both the uncorrected and corrected data sets. As seen here, the corrected method has not only corrected the mean but also has significantly reduced the standard deviation (noise) of the measurement. All values are in °C.

| Exp # | Uncorrected | Corrected with field maps | Corrected with image phase (referenceless) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | |

| 1 | −4.25 | 2.84 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.16 |

| 2 | −2.06 | 1.15 | −0.04 | 0.27 | 0.60 | 0.34 |

| 3 | 2.01 | 1.27 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.76 | 0.38 |

Phantom heating experiment with simulated breath holds

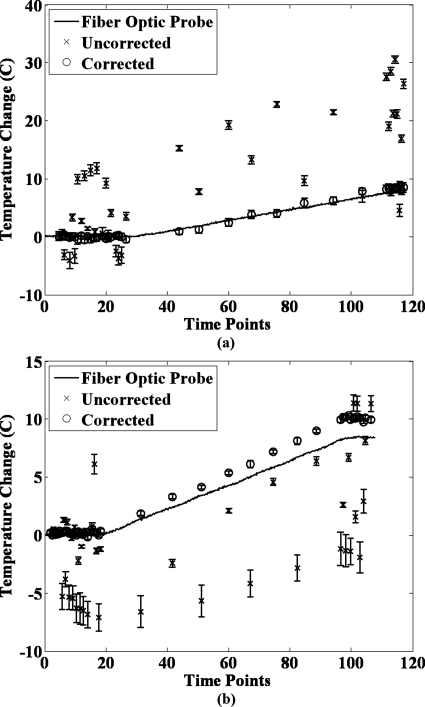

A plot showing the fiber optic probe temperature, the uncorrected PRFS temperature in the water gelatin, and the temperature after correction with measured field changes fit using the LSSP method is shown in Fig. 7 for the two experiments performed. The average root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the PRFS temperature values from the fiber optic temperature profile is shown in Table 3 for the uncorrected and corrected data sets. Corrected data sets shown include the correction with field changes and correction with image phase changes (the simple referenceless method).

Figure 7.

Uncorrected and corrected temperatures in the water gelatin (simulated tumor) for the second phantom heating experiment. These are shown plotted against the temperature change measurements from the fiber optic temperature probes. Notice how the corrected temperature closely tracks the fiber optic temperature, while the uncorrected temperature has large errors. These errors are of greater magnitude than would most likely be seen in vivo, but can function as a worst case scenario. Also, note that the error bars are typically much smaller for the corrected data than for the uncorrected data. However, the error bars for the uncorrected data can occasionally be very small, when the spatial inhomogeneity of the field changes in the tumor happened to be small.

Table 3.

Average root mean squared (RMS) deviation of phase changes (expressed as equivalent temperature change in °C) from the measured fiber optic temperature across all time points of the two heating experiments for both the uncorrected and corrected data sets. Notice the large decrease in the deviation in using field maps as opposed to image phase.

| Exp # | Average RMS deviation (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected | Corrected with field maps | Corrected with image phase (referenceless) | |

| 1 | 10.39 | 0.54 | 1.17 |

| 2 | 5.05 | 0.98 | 1.80 |

In vivo breast experiment

A MR image of the volunteer’s right breast inside the applicator is shown in Fig. 8, along with images of the MP-IDEAL separated water and fat components of the image. Finally, plots of the temperature over time are shown for two regions of the glandular tissue in Fig. 9. The mean and standard deviation of the uncorrected and corrected data sets for the volunteer experiment are shown in Table 4.

Figure 8.

(a) Magnitude image of the volunteer’s right breast in the applicator. (b) Fat and (c) water separated images of the in vivo breast experiment using MP-IDEAL

Figure 9.

(Left) ROIs of pixels used in the left side of the glandular tissue used for sampling, (right) plot of the uncorrected and corrected phase changes (expressed as equivalent temperature change in °C) across all time points for all ROIs. Temperature change (vertical scale, °C) was calculated in reference to the temperature at the first breath hold.

Table 4.

Mean and standard deviation of phase changes (expressed as equivalent temperature change in °C) of all time points of the uncorrected and corrected data sets for the nonheating in vivo breast experiment. Notice the reduction in the mean and, in particular, the standard deviation for the corrected data compared to the uncorrected data. All values are in °C.

| Exp # | Uncorrected | Corrected with field maps | Corrected with image phase (referenceless) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | |

| Left | 3.39 | 1.93 | −1.92 | 0.79 | −0.46 | 0.83 |

| Right | 2.95 | 2.42 | −1.85 | 0.42 | −2.05 | 0.81 |

DISCUSSION

The work presented in this paper has shown the feasibility and accuracy of using field changes measured using multiecho fitting techniques in fatty tissue to correct for field changes in water-rich regions of the breast caused by typical variation of breath holds. The results of the nonheating phantom experiments (shown in Fig. 6) demonstrate good correction of the field changes induced between real human breath holds, reducing errors on the order of 5–10 °C to less than 1 °C. Table 2 shows that correction with both the field fitting method and referenceless method results in a mean temperature much closer to 0 °C. In this situation one would expect that they would be equivalent since the reference tissue is not heated and thus would not have errors due to temperature change PRFS effects in the water component. Just as important, the standard deviation was largely reduced by correction. Note that it is very unlikely that the phantom had any significant temperature change during the experiments since they never lasted longer than 20 min, which is very little time for temperature changes to occur in the middle of the phantom where the correction was evaluated.

The results of the heating phantom experiments show that correction with field changes (our proposed method) is effective even when temperature changes are present. The field changes induced by the simulated breath holds were spatially similar to the field changes observed with volunteer breath holds. While the magnitude of the field changes was larger than those seen with volunteer breath holds, we feel these experiments function as worst case scenarios. Figure 7 shows that correction with field change measurements results in temperature values that are much closer to the fiber optic temperature values than without correction. While the oscillations of the simulated breath holds occasionally brought the uncorrected temperature close to the temperature of the fiber optic probe, the overall uncorrected error was very large. Results in Table 3 demonstrate that the temperature deviation from the fiber optic temperature was largely reduced by both correction methods. However, the correction with field changes performed much better than the correction with image phase, resulting in almost half the error. This was expected, since the temperature increase induces phase changes in the water signal in the fat gelatin, producing error in the fit phase changes. These temperature changes are accounted for in the field fit, removing it as a source of error. Thus, these results demonstrate that the field fitting method provides more accurate correction under the presence of widespread temperature changes compared to using the simple referenceless method. Finally, small errors between the corrected temperature and the fiber optic temperature can be seen near the end of the experiments. This could be due to the fiber optic probe being slightly out of the slice used for MR temperature measurement and thus sampling a slightly different temperature change. Also, it is possible for susceptibility changes to result in thermometry errors.37, 38 However, it is unlikely these errors would be large considering that the experiments were performed parallel to the B0 field, as opposed to perpendicular in the previous studies.

While we compare the field measurement method presented in this paper with the simple referenceless method, there are other methods for correction of phase changes due to breathing. These include the use of navigator echoes for respiratory gating39, 40, 41 and phase correction using reference images taken at multiple stages of the breathing cycle.21, 42 Future work will investigate possible use of the present method in combination with these methods.

The in vivo breast experiment demonstrates that correction of breath hold field changes can be achieved in the glandular tissue of the breast, as seen in Fig. 9. The results in Table 4 show that while the mean was not corrected to 0 °C in some cases (as would be expected since no heat was applied), the standard deviation was largely reduced compared to the uncorrected temperature values. The correction could not be evaluated in the middle of the glandular tissue due to the presence of a small region of fatty tissue, since it did not mimic the conditions that would be found in a water-rich tumor. Also, the correction was less effective around the edges of the glandular tissue region. This is most likely due to the small amount of fat present in the breast. Also, the fat in the breast is more inhomogenous than the fat in the phantom, potentially leading to error. The SNR and field fitting in the chest wall were worse than in the breast, which may have contributed some error. Lastly, very slight movements of the breast were seen at two of the time points, which could have contributed to some of the error. However, correction in the majority of the glandular tissue resulted in reducing errors of 8 °C to less than 2 °C. This correction is particularly good considering the nature of the breast used in this study. A typical breast cancer patient is older and thus fatty tissue has replaced much of the glandular tissue. Thus, there would be much more fatty tissue in the breast to use for fitting and most likely a smaller water rich region. The in vivo results discussed here show great promise for this method in vivo. However, a more in depth study in patients with locally advanced breast cancer, preferably with heating, is best suited for further work. Lastly, processing time for each time point was approximately 3–5 min on a standard laptop computer. This could be lowered to less than a minute with a more powerful dedicated workstation for real-time analysis.

CONCLUSION

Breathing motion can create large errors when performing MR thermometry in the breast due to changes in the B0 field. In this paper, we have developed an extension of the referenceless method to correct for these errors using multiecho fitting methods to fit for the B0 field in the fatty tissue and using measured field changes as references to extrapolate field corrections into a water-only (tumor) region. This technique has been validated in a number of situations, including nonheating phantom experiments with human breath holds, phantom experiments with heating and simulated breath holds, and in a healthy female breast. In all cases the correction method has been shown to greatly reduce temperature error in water-rich regions. The method has also been shown to be an improvement over similar methods that use image phase changes instead of field changes, particularly when temperature changes are induced. While the healthy breast results show good correction in the glandular regions, future work is needed to assess the accuracy of the technique in a large number of subjects with breast cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge NCI Grant No. PO1-CA042745 and NIH Grant No. T32-EB001040 for supporting this research.

References

- Dewhirst M., Jones E., Samulski R. J., Vujaskovic Z., Li C., and Prosnitz L., in Cancer Medicine 6, edited by Kufe D. W.et al. (BC Decker, Hamilton, 2003), pp. 623–636. [Google Scholar]

- Falk M. H. and Issels R. D., “Hyperthermia in oncology,” Int. J. Hyperthermia 17, 1–18 (2001). 10.1080/02656730150201552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wust P., Hildebrandt B., Sreenivasa G., Rau B., Gellermann J., Riess H., Felix R., and Schlag P. M., “Hyperthermia in combined treatment of cancer,” Lancet Oncol. 3, 487–497 (2002). 10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00818-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand J. W., Machin D., Vernon C. C., and Whaley J. B., “Analysis of thermal parameters obtained during phase III trials of hyperthermia as an adjunct to radiotherapy in the treatment of breast carcinoma,” Int. J. Hyperthermia 13, 343–364 (1997). 10.3109/02656739709046538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp D. S. and Cox R. S., “Thermal treatment parameters are most predictive of outcome in patients with single tumor nodules per treatment field in recurrent adenocarcinoma of the breast,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 33, 887–899 (1995). 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00212-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleson J. R., Samulski T. V., Leopold K. A., Clegg S. T., Dewhirst M. W., Dodge R. K., and George S. L., “Sensitivity of hyperthermia trial outcomes to temperature and time: Implications for thermal goals of treatment,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 25, 289–297 (1993). 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90351-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seegenschmiedt M. H., Martus P., Fietkau R., Iro H., Brady L. W., and Sauer R., “Multivariate analysis of prognostic parameters using interstitial thermoradiotherapy (IHT-IRT): Tumor and treatment variables predict outcome,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 29, 1049–1063 (1994). 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90401-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherar M., Liu F. F., Pintilie M., Levin W., Hunt J., Hill R., Hand J., Vernon C., van Rhoon G., van der Zee J., Gonzalez D. G., van Dijk J., Whaley J., and Machin D., “Relationship between thermal dose and outcome in thermoradiotherapy treatments for superficial recurrences of breast cancer: Data from a phase III trial,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 39, 371–380 (1997). 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00333-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter D. L., MacFall J. R., Clegg S. T., Wan X., Prescott D. M., Charles H. C., and Samulski T. V., “Magnetic resonance thermometry during hyperthermia for human high-grade sarcoma,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 40, 815–822 (1998). 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00855-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg S. T., Das S. K., Zhang Y., Macfall J., Fullar E., and Samulski T. V., “Verification of a hyperthermia model method using MR thermometry,” Int. J. Hyperthermia 11, 409–424 (1995). 10.3109/02656739509022476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciunescu O. I., Das S. K., McCauley R. L., MacFall J. R., and Samulski T. V., “3D numerical reconstruction of the hyperthermia induced temperature distribution in human sarcomas using DE-MRI measured tissue perfusion: Validation against non-invasive MR temperature measurements,” Int. J. Hyperthermia 17, 221–239 (2001). 10.1080/02656730110041149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciunescu O. I., Raaymakers B. W., Kotte A. N., Das S. K., Samulski T. V., and Lagendijk J. J., “Discretizing large traceable vessels and using DE-MRI perfusion maps yields numerical temperature contours that match the MR noninvasive measurements,” Med. Phys. 28, 2289–2296 (2001). 10.1118/1.1408619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciunescu O. I., Samulski T. V., MacFall J. R., and Clegg S. T., “Perturbations in hyperthermia temperature distributions associated with counter-current flow: Numerical simulations and empirical verification,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 47, 435–443 (2000). 10.1109/10.828143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFall J. R., Prescott D. M., Charles H. C., and Samulski T. V., “1H MRI phase thermometry in vivo in canine brain, muscle, and tumor tissue,” Med. Phys. 23, 1775–1782 (1996). 10.1118/1.597760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samulski T. V., Clegg S. T., Das S., MacFall J., and Prescott D. M., “Application of new technology in clinical hyperthermia,” Int. J. Hyperthermia 10, 389–394 (1994). 10.3109/02656739409010283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Le T. H., Parrish T., and Erhard P., “Retrospective estimation and correction of physiological fluctuation in functional MRI,” Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 201–212 (1995). 10.1002/mrm.1910340211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gelderen P. and Moonen C. T. W., “Respiration induced changes of field homogeneity in the brain: Implications for fMRI,” Sixth Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Sydney, Australia, 1998.

- Van de P. -Fr., Josef M. P., Gary H. G., Kamil U., and Xiaoping H., “Respiration-induced B0 fluctuations and their spatial distribution in the human brain at 7 Tesla,” Magn. Reson. Med. 47, 888–895 (2002). 10.1002/mrm.10145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolan P. J., Henry P. G., Baker E. H., Meisamy S., and Garwood M., “Measurement and correction of respiration-induced B0 variations in breast 1H MRS at 4 Tesla,” Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 1239–1245 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.20277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicky H. G. M. P., Lambertus W. B., Sara M. S., Koen L. V., and Chris J. G. B., “Do respiration and cardiac motion induce magnetic field fluctuations in the breast and are there implications for MR thermometry?” J. Magn. Reson Imaging 29, 731–735 (2009). 10.1002/jmri.21680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey S., Maclair G., de Senneville B. D., Lepetit-Coiffe M., Berber Y., Kohler M. O., Quesson B., Moonen C. T., and Ries M., “Online correction of respiratory-induced field disturbances for continuous MR-thermometry in the breast,” Magn. Reson. Med. 61, 1494–1499 (2009). 10.1002/mrm.21954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempp H., Martirosian P., Boss A., Clasen S., Kickhefel A., Kraiger M., Schraml C., Claussen C., Pereira P., and Schick F., “MR temperature monitoring applying the proton resonance frequency method in liver and kidney at 0.2 and 1.5 T: Segment-specific attainable precision and breathing influence,” MAGMA (N.Y.) 21, 333–343 (2008). 10.1007/s10334-008-0139-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques J. P. and Bowtell R., “Application of a Fourier-based method for rapid calculation of field inhomogeneity due to spatial variation of magnetic susceptibility,” Concepts Magn. Reson., Part B 25B, 65–78 (2005). 10.1002/cmr.b.20034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raj D., Paley D. P., Anderson A. W., Kennan R. P., and Gore J. C., “A model for susceptibility artefacts from respiration in functional echo-planar magnetic resonance imaging,” Phys. Med. Biol. 45, 3809–3820 (2000). 10.1088/0031-9155/45/12/321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rares S. S., de Denis B., and Chrit T. W. M., “A fast calculation method for magnetic field inhomogeneity due to an arbitrary distribution of bulk susceptibility,” Concepts Magn. Reson., Part B 19B, 26–34 (2003). 10.1002/cmr.b.10083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plathow C., Ley S., Zaporozhan J., Schobinger M., Gruenig E., Puderbach M., Eichinger M., Meinzer H. P., Zuna I., and Kauczor H. U., “Assessment of reproducibility and stability of different breath-hold maneuvres by dynamic MRI: Comparison between healthy adults and patients with pulmonary hypertension,” Eur. Radiol. 16, 173–179 (2006). 10.1007/s00330-005-2795-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. L., Riederer S. J., Rossman P. J., Grimm R. C., Debbins J. P., and Ehman R. L., “A monitoring, feedback, and triggering system for reproducible breath-hold MR imaging,” Magn. Reson. Med. 30, 507–511 (1993). 10.1002/mrm.1910300416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K., Oshio K., Chung A. H., Hynynen K., and Jolesz F. A., “Temperature mapping using the water proton chemical shift: A chemical shift selective phase mapping method,” Magn. Reson. Med. 38, 845–851 (1997). 10.1002/mrm.1910380523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke V., Vigen K. K., Sommer G., Daniel B. L., Pauly J. M., and Butts K., “Referenceless PRF shift thermometry,” Magn. Reson. Med. 51, 1223–1231 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.20090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N., Tempany C., Jolesz F., and Hynynen K., “Evaluation of referenceless thermometry in MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery of uterine fibroids,” J. Magn. Reson Imaging 28, 1026–1032 (2008). 10.1002/jmri.21506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke V., Kinsey A. M., Ross A. B., Nau W. H., Diederich C. J., Sommer G., and Pauly K. B., “Referenceless MR thermometry for monitoring thermal ablation in the prostate,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 26, 813–21 (2007). 10.1109/TMI.2007.892647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt C., Soher B. J., and MacFall J. R., “Optimal multi-echo water-fat separated imaging parameters for temperature change measurement using Cramer-Rao bounds,” Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Stockholm, Sweden, 1–7 May 2010.

- Wyatt C., Soher B. J., and MacFall J. R., “Temperature and B0 field measurement bias of multi-echo fat-water fitting algorithms,” Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Stockholm, Sweden, 1–7 May 2010.

- Ishihara Y., Calderon A., Watanabe H., Okamoto K., Suzuki Y., and Kuroda K., “A precise and fast temperature mapping using water proton chemical shift,” Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 814–823 (1995). 10.1002/mrm.1910340606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt C. et al. , “Hyperthermia MRI temperature measurement: Evaluation of measurement stabilisation strategies for extremity and breast tumours,” Int. J. Hyperthermia 25, 422–433 (2009). 10.1080/02656730903133762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Shimakawa A., McKenzie C. A., Brodsky E., Brittain J. H., and Reeder S. B., “Multiecho water-fat separation and simultaneous R2* estimation with multifrequency fat spectrum modeling,” Magn. Reson. Med. 60, 1122–1134 (2008). 10.1002/mrm.21737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters R. D., Hinks R. S., and Henkelman R. M., “Heat-source orientation and geometry dependence in proton-resonance frequency shift magnetic resonance thermometry,” Magn. Reson. Med. 41, 909–918 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinkhuizen S. M., Bakker C. J., and Bartels L. W., “PRFS-based MR thermometry is hampered by susceptibility changes caused by the heating of fat: Experimental demonstration,” Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Stockholm, Sweden, 2010.

- de Zwart J. A., Vimeux F. C., Palussiere J., Salomir R., Quesson B., Delalande C., and Moonen C. T., “On-line correction and visualization of motion during MRI-controlled hyperthermia,” Magn. Reson. Med. 45, 128–137 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeuffer J., Van de Moortele P. F., Ugurbil K., Hu X., and Glover G. H., “Correction of physiologically induced global off-resonance effects in dynamic echo-planar and spiral functional imaging,” Magn. Reson. Med. 47, 344–353 (2002). 10.1002/mrm.10065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigen K. K., Daniel B. L., Pauly J. M., and Butts K., “Triggered, navigated, multi-baseline method for proton resonance frequency temperature mapping with respiratory motion,” Magn. Reson. Med. 50, 1003–1010 (2003). 10.1002/mrm.10608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmatukha A. V. and Bakker C. J., “Correction of proton resonance frequency shift temperature maps for magnetic field disturbances caused by breathing,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 4689–4705 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/18/015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]