Abstract

Purpose: Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is the state of the art technique for head and neck cancer treatment. It requires precise delineation of the target to be treated and structures to be spared, which is currently done manually. The process is a time-consuming task of which the delineation of lymph node regions is often the longest step. Atlas-based delineation has been proposed as an alternative, but, in the authors’ experience, this approach is not accurate enough for routine clinical use. Here, the authors improve atlas-based segmentation results obtained for level II–IV lymph node regions using an active shape model (ASM) approach.

Methods: An average image volume was first created from a set of head and neck patient images with minimally enlarged nodes. The average image volume was then registered using affine, global, and local nonrigid transformations to the other volumes to establish a correspondence between surface points in the atlas and surface points in each of the other volumes. Once the correspondence was established, the ASMs were created for each node level. The models were then used to first constrain the results obtained with an atlas-based approach and then to iteratively refine the solution.

Results: The method was evaluated through a leave-one-out experiment. The ASM- and atlas-based segmentations were compared to manual delineations via the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) for volume overlap and the Euclidean distance between manual and automatic 3D surfaces. The mean DSC value obtained with the ASM-based approach is 10.7% higher than with the atlas-based approach; the mean and median surface errors were decreased by 13.6% and 12.0%, respectively.

Conclusions: The ASM approach is effective in reducing segmentation errors in areas of low CT contrast where purely atlas-based methods are challenged. Statistical analysis shows that the improvements brought by this approach are significant.

Keywords: active shape mode, image registration, image segmentation, head and next IMRT, lymph nodes

INTRODUCTION

As one of the state of the art techniques for head and neck cancer treatment, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) requires a precise delineation of both the target volume and the structures to be spared. Manually delineating contours in CT images, which is the standard of care, is a lengthy process even for an experienced physician. One of the most time-consuming tasks is the delineation of the cervical lymph node chain and the surrounding normal anatomical structures of the head and neck. The process of bilateral lymph node definitions for the entire neck can typically take between 20 and 45 min, depending on the patient’s level of complexity. In contrast, delineation of the gross tumor volume typically requires on the order of 5 min or less. Furthermore, for many cancers of the head and neck, there is almost always some risk of spread of cancer to the cervical (neck) lymph nodes. In many cases, the lymph nodes have microscopic disease even when they appear completely normal on CT, PET, or MRI. Instead of having a patient undergo a surgical sampling of all the lymph nodes of the neck, it is a standard practice to deliver radiation prophylactically to these regions even when there is no radiological evidence of enlargement. An automatic technique capable of segmenting normal-looking lymph nodes could thus have a significant impact on the daily clinical load.

Atlas-based segmentation has been proposed as an approach to segment the lymph nodes. In this approach, structures of interest are delineated manually in one reference volume commonly called the atlas. This reference volume is then registered to other volumes to be segmented using rigid and nonrigid registration methods. The transformation that registers the reference volume to the other volumes can then be used to project contours from the atlas to the patient volumes. This approach is commonly used to segment brain structures in well-contrasted high resolution MR images, while only some have used it for segmenting head and neck structures in CT images. Chao et al.1 used an enhanced Demons algorithm to register a template image to patient images and used the transformations to delineate the lymph nodes, the left and right parotid glands, the spinal cord, and the brainstem. Instead of using these automatically generated contours directly, they presented contours to physicians for modification and then compared these edited contours to manual delineations. In another study, Commowick et al.2 projected lymph node contours from an average image volume to patient CT images using global affine and local nonrigid transformations. Although the volume-based error measure showed that, overall, the atlas-based delineations were acceptable, oversegmentations of the lymph node regions were observed. In a follow up study, Commowick et al.3 proposed a scheme to select the most locally similar images to the patient image from a series of reference images, thus using several atlas volumes to segment the structures of interest. The quantitative validation performed in this study showed an improvement in specificity compared to a standard atlas-based method as well as a reduction in sensitivity. Gorthi et al.4 also used an atlas-based approach, but the deformation was computed with structures easily visible in the images (bones, trachea, and skin) and then applied to the rest of the image. This led to relatively large (14.52–21.81 mm) segmentation errors for the average Hausdorff distance for node levels II–IV.

Although comparison between techniques is difficult without testing them on the same image volumes, our experience indicates that lymph node segmentation is a challenge for purely intensity-based atlas-based methods because typical CT images for head and neck IMRT generally do not have particularly high resolution and because the contrast between lymph node regions and their surrounding regions is often poor. In this study, we complement an atlas-based approach with an active shape model (ASM) approach5 to bring a priori information about the shapes of the structures in the segmentation process and constrain the deformation. The work we present herein initializes the ASM method with the result of an atlas-based, registration-driven approach. The ASM is constructed using a technique based on the method proposed by Frangi et al.,6 and the search algorithm for adapting the ASM is a variation in the local gray-level model proposed by Cootes et al.7 In the remainder of this article, we describe our segmentation method and compare it to a purely atlas-based technique.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data description

The CT images used in this study with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval are deidentified images from patients who underwent IMRT treatment for larynx and base of tongue cancers. We selected 15 volumes with no or minimally enlarged lymph nodes. They have a voxel size of around 1 mm in the x and y directions and a slice thickness of 3 mm. The images are acquired with a Philips (Philips Healthcare, The Netherlands) Brilliance Big Bore CT scanner with the patient injected with 80 ml of Optiray 320, a 68% iversol-based nonionic contrast agent (manufactured by Mallinckrodt Inc., Hazelwood, MO). Typically, the images cover the head, the neck, and the upper chest.

For all 15 volumes, level II–IV lymph node regions on the right side were delineated following the published guidelines8 by the first author and reviewed carefully by two radiation oncologists (K.N. and L.M.). These manual delineations were saved in the form of binary masks as well as contours and were used to construct the ASM and validate the results of the experiments.

Construction of ASM through registration

A prerequisite for creating active shape models is to establish a correspondence between points on the training shapes. Since it is difficult to manually localize corresponding points on a set of 3D surfaces, we used a method inspired by the work of Frangi et al.,6 who used both affine and nonrigid registrations for model building. The transformations produced by the registration process are used to relate points representing the shapes in different training images.

Construction of an average image volume

For the construction of the reference shape onto which all training shapes are aligned, an average image volume representing the centroid of the images is first constructed using the procedure proposed by Guimond et al.9 In this procedure, one volume in the set of images is chosen as a target. All the other volumes are subsequently registered to this target by a standard intensity-based affine registration algorithm that uses the normalized mutual information (NMI) (Ref. 10) as similarity measure and then further registered by an intensity-based nonrigid registration technique. The nonrigid registration is performed by the adaptive basis algorithm11 we proposed in the past. This algorithm also uses the NMI as similarity measure and models the deformation fields as a linear combination of radial basis functions with finite support,

| (1) |

where Φ is one of Wu’s compactly supported positive radial basis functions,12’s are the coefficients to be optimized, and N is the number of basis functions (more details on this algorithm can be found in Ref. 11). The major adjustable parameters determining the performance of the algorithm include the number of basis functions to be placed, a parameter controlling the difference between the coefficients of the adjacent basis functions, which is used to adjust the stiffness of the transformation (small values for this parameter lead to transformations that are more regularized than transformations obtained with large values), and the range of intensities used to compute the intensity histograms from which the NMI between images is estimated (adjusting this range permits to compute transformations that are driven, for instance, by soft tissue regions, by bony structures, or both). The algorithm produces transformations between a source and a target volume and between the target and the source volume that are constrained to be inverses of each other. To create the average volume, the forward transformations (from T1 to Tk) registering the source images (i.e., the set of available image volumes) to the current average and their inverses (from to ) are computed. The forward transformations are applied to the source images and the resulting images are intensity-averaged. The inverse transformations are averaged and the resulting transformation is applied to the current intensity average to produce a volume that is both an intensity and a shape average of all the volumes, and the process is repeated until convergence. It has been shown in Ref. 9 that the final image volume is not dependent on the volume chosen to initiate the process, thus reducing the potential bias introduced by selecting a particular volume as the initial reference. Note that the nonrigid registrations are performed on the full scale images, with an isotropic density of basis functions at 16 mm per basis function, an experimentally determined stiffness value of 0.3, and the full intensity range. This parameter setting produces adequately regularized transformations with which the bones, body boundaries, and soft tissue regions are registered.

Establishing point correspondence for the creation of the ASM

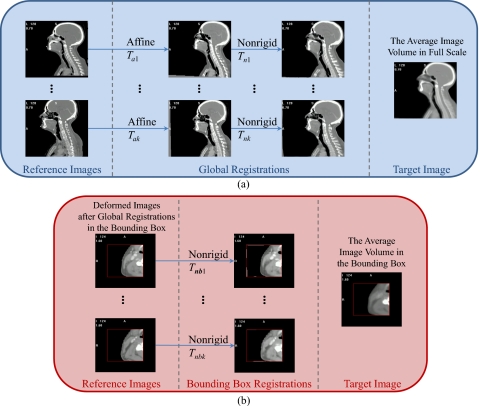

Once the average volume is created, registrations are performed to acquire the transformations needed to find point correspondence. As shown in Fig. 1, the process starts with an affine registration [Fig. 1a] to align the images with the average volume, which produces transformations from Ta1 to Tak. Even though after affine registration the images are aligned in the same space, the head and neck areas are not aligned accurately because the neck is much more flexible than some other structures such as the head. Large discrepancies in this area also exist between patients, including neck thickness, length and bending of the cervical vertebrae, and large anatomical differences in the surrounding soft tissues. A two-step nonrigid registration process is applied to compensate for these differences. First, a registration is performed on the full scale images to align mainly the bones and the body boundaries in each image and in the average volume. The same parameter setting as the one used for constructing the average volume is used, except that the value of the stiffness parameters is reduced to 0.2 such that highly regularized transformations from Tn1 to Tnk are obtained. Second, a bounding box surrounding the lymph node regions and extending from the inferior part of the skull to the bottom of the clavicle is defined on the average volume and then copied onto the other images that are registered after the first step. When registering the images in the bounding boxes, as shown in Fig. 1b, the density of the basis functions is increased to 8 mm per basis function, the stiffness value is set at 0.3, and the intensity range is set to cover soft tissues such that transformations that are less regularized and driven mainly by soft tissue regions are obtained. This permits to register the lymph node regions and their peripheral areas more accurately. The transformations from Tnb1 to Tnbk are obtained as well as their inverses.

Figure 1.

Flow charts illustrating the process used to register the training images and the average image volume. Panel (a): Full scale image. Panel (b): Registration in the bounding box containing the nodes.

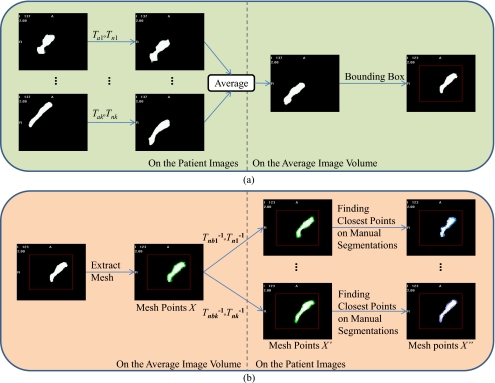

With all the transformations computed, the ASM is created following the steps shown in Fig. 2. First, as shown in Fig. 2a, the manually segmented structures from each of the volumes in the form of binary masks are projected onto the average volume by applying the affine transformations from Ta1 to Tak and then the nonrigid transformations from Tn1 to Tnk. The projections are then averaged and thresholded to form a single binary mask representing the lymph node regions in the average volume. Several anatomical landmarks are subsequently identified manually in the average volume to separate this binary mask into three parts. These include the lower border of the hyoid, which separates levels II and III, and the lower margin of the cricoid cartilage, which divides levels III and IV. The landmarks define two flat surfaces separating the mask into three sections, representing level II–IV lymph node regions. As shown in Fig. 2b, surfaces are extracted from the binary objects in the bounding box using the ITK implementation of the marching cube algorithm.13 This defines meshes in the space of the average volume in the bounding box for the three node levels. Correspondence between these points and points in each of the other images is established in two steps. First, the inverses of the transformations obtained from the nonrigid registrations in the bounding boxes, which are denoted as Tnb1−1 to Tnbk−1, are applied to these points. Next, the inverses of the transformations computed in the global nonrigid registration step, which are denoted as Tn1−1 to Tnk−1, are applied. For each vertex X, this produces a point X′, which is mapped back into the space where all the images are affinely registered. Second, the correspondence is refined for points X′ that do not belong to the separating surfaces by finding the closest point X″ to X′ on the manually segmented surfaces projected into the affinely aligned image space. This compensates for the inaccuracy in the registration process. The X″ points are then used to compute the modes of variations or the structures of interest following the method described by Cootes et al.5 The x, y, and z coordinates of the landmarks are concatenated into k vectors ’s, for which a principal component analysis is performed to obtain a linear model of shapes for each node level in the form of

| (2) |

where is the mean shape, is the matrix of the first t eigenvectors associated with the highest eigenvalues of the covariance matrix, and is the vector of model parameters. Notice that the models are built in the space where all images are aligned using affine registrations; this is because the ASM should focus on describing shape variations while excluding discrepancies due to large differences in the patient orientation.

Figure 2.

Flow charts illustrating the process used for the construction of the ASM using transformations obtained from registrations. Panel (a): Creation of the mask in the average volume. Panel (b): Establishing point correspondence to create the ASM.

Segmentation of new images

A new image is segmented as follows. First, the image is registered to the average volume using an affine and then a nonrigid global transformation computed as described earlier. The bounding boxes are extracted and nonrigid registration is performed again locally on these regions. The two nonrigid registrations produce displacement vectors for all the vertices on the structure of interest and map them from the average volume onto the affinely aligned image, forming a new shape. The active shape model is used to constrain the new shapes to conform to a shape compatible with the training set. This is accomplished by computing the linear combination of the modes of variation that best captures the new shape. Suppose the new shape is denoted as , the goal is to find the transformation T and model parameters such that the new shape can be estimated as

| (3) |

which is solved as a least-squares estimation problem.

The resulting first segmentation is subsequently refined. For each vertex, a search vector is computed in the direction of the structure’s surface normal, and possible boundary points are localized along this surface normal. A local gray-level model is then applied to determine which one of these candidate points can be selected as the best boundary point.

The local gray-level model is built based on that proposed by Cootes et al.7 For each point sitting on the manually delineated surface of a training image, the surface normal is calculated, and the intensity profile along the normal direction is sampled. For the corresponding points over the k training images, a total of k profiles is computed. The profiles can be built using a number of image properties such as the intensity or the intensity gradient. We explored several options, including the image intensity, gradient, and normalized gradient which is calculated as

| (4) |

where is the original gradient vector for point i with values gxi, gyi, and gzi on each direction, and is the normalized gradient vector. We opted to use the normalized gradient of the training images because of its relative insensitivity to intensity variations caused by contrast agent washout in different patient images.

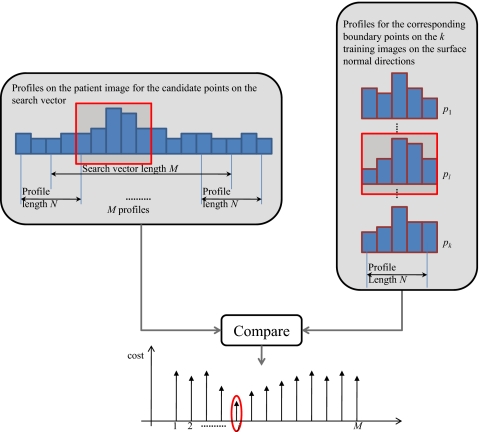

Figure 3 illustrates how the best boundary point is chosen from a set of M candidate points along the surface normal search vector. At each point along the search vector, we extract a profile of length N for the candidate point and points on either side. We then compare this profile to the k profiles in the gray-level model. The cost is computed for each profile and the lowest cost is stored as the cost of the candidate point in question. The cost Cj for the jth candidate point is computed as the Euclidean distance between the profile of the candidate point, , and the profiles in the model, ,

| (5) |

where is the Euclidean distance between two vectors. The candidate point along the search vector with the lowest cost is chosen as the new boundary. After all vertices are updated through this process, the displacements are constrained by the ASM, generating the shape for the next iteration. The process is repeated until successive iterations converge on a shape or a maximum number of iterations is reached. After the meshes for the three levels of lymph node regions are obtained, they are converted into binary masks and combined into one mask as the union of the three.

Figure 3.

Search for the point on the search vector with the best fit to the gray-level model. The entire search vector consists of M candidates points. At each candidate point on the search vector, a profile of length N is calculated. These profiles are compared to analogous profiles in the training images.

Running time

The affine and nonrigid registration algorithms used in this study are implemented in C and C++. Typical running time on a computer with a 2.93 GHz Intel Xeon quad-core PC with the 64-bit Windows OS and 16 GB of memory is 2 min for the global affine component, 10 min for the global nonrigid component, and 3 min for the local nonrigid component. The model-fitting component is still implemented in MATLAB and takes on the order of 6 min.

RESULTS

All 15 volumes were used to create the average volume because the final volume is not sensitive to the volume chosen to initialize the process and to generate the average node mask in the average volume. Then, a leave-one-out strategy was used to create the ASMs and the intensity models and to evaluate these. For each run, one volume was eliminated from the image set, and the model was created using the remaining 14 volumes. This model was used to segment the 15th volume and the process was repeated 15 times. Validation was performed by comparing the automatic segmentation to a manual delineation used as the reference standard for comparison. The Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) (Ref. 14) was used to evaluate the volumetric overlap between the manual and the automatic segmentations. DSC is defined in Eq. 6 as the overlap of two volumes normalized to their mean volume, where A and B represent the two binary segmentations and the notation N(A) represents the number of voxels contained in segmentation A,

| (6) |

The DSC is defined on [0, 1], where 0 indicates no overlap and 1 indicates identical segmentations with exact overlap. Volumetric measures such as the DSC can be insensitive to boundary displacements that are small compared to the structure’s size. To provide additional information, we calculated the Euclidean distance between the surfaces of the ASM-based and manual segmentations. To gauge the effect of the model on the segmentation, we also compared the results obtained with the method we proposed and the results obtained solely with an atlas-based approach.

Table 1 shows that in all 15 cases the ASM-based segmentations have a higher DSC than those obtained with a purely atlas-based method; the improvement brought by the method we proposed ranges from 4.1% to 20.4% with an overall improvement of 10.7%.

Table 1.

DSC comparing atlas-based and manual segmentations, and ASM-based and manual segmentations.

| Patient | DSC_atlas | DSC_ASM | Improvement in % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.563 | 0.678 | 20.43 |

| 2 | 0.528 | 0.599 | 13.45 |

| 3 | 0.689 | 0.723 | 4.93 |

| 4 | 0.696 | 0.731 | 5.03 |

| 5 | 0.663 | 0.717 | 8.14 |

| 6 | 0.603 | 0.689 | 14.26 |

| 7 | 0.642 | 0.705 | 9.81 |

| 8 | 0.632 | 0.711 | 12.50 |

| 9 | 0.657 | 0.684 | 4.11 |

| 10 | 0.667 | 0.764 | 14.54 |

| 11 | 0.524 | 0.546 | 4.20 |

| 12 | 0.689 | 0.748 | 8.56 |

| 13 | 0.651 | 0.760 | 16.74 |

| 14 | 0.612 | 0.728 | 18.95 |

| 15 | 0.646 | 0.680 | 5.26 |

| Mean | 0.631 | 0.698 | 10.73 |

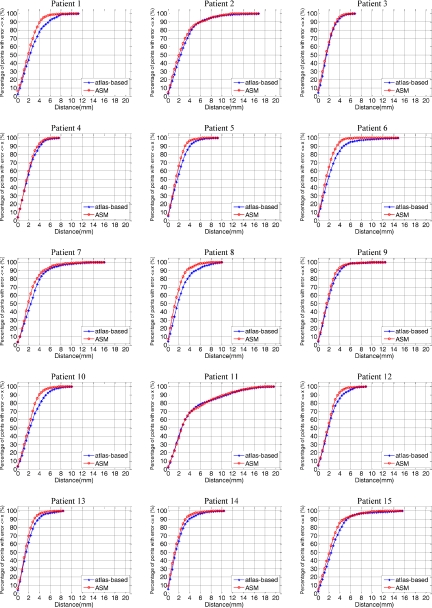

The mean, median, and maximum distances to the manual surface are shown in Table 2. In this table, Mean_atlas, Median_atlas, and Max_atlas refer to the results obtained with atlas-based segmentation alone. Mean_ASM, Median_ASM, and Max_ASM are the results obtained with the method we propose. For these three measures, Table 2 also presents the percent improvements brought by the model-based approach. These range from 0% to 26.3% for the means, from −3.7% to 24.0% for the medians, and from 2.3% to 53.6% for the max errors. The only case for which no improvement has been observed is case 11. This is a special case because a tumor located in the trachea pushed the thyroid to where vessels are normally located in level IV lymph node region. Because of this, the registration step was inaccurate. The model was thus also initialized incorrectly and converged to the wrong solution. One-sided t-tests were performed to test the statistical significance of the differences observed for the DSC, mean, median, and max values. In all cases, these differences were significant (p<0.01). Figure 4, which shows cumulative distributions for the surface error for each volume (i.e., the x axis is a distance error and the y axis is the percentage of points for which the error is smaller than this distance), illustrates the effect of the model on the segmentation error. In all cases except for patient 11, the cumulative distribution curve for the model-based approach is above the curve for the atlas-based approach.

Table 2.

Mean, median, and max error values for the atlas-based (Mean_atlas, Median_atlas, and Max_atlas) and for the ASM-based method we propose (Mean_ASM, Median_ASM, and Max_ASM) in mm.

| Patient | Mean_atlas | Mean_ASM | Improvement In % | Median_atlas | Median_ASM | Improvement in % | Max_atlas | Max_ASM | Improvement in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.87 | 2.29 | 20.20 | 2.48 | 2.13 | 13.96 | 11.53 | 10.02 | 13.10 |

| 2 | 3.10 | 2.95 | 4.89 | 2.56 | 2.25 | 12.09 | 17.10 | 11.95 | 30.09 |

| 3 | 1.96 | 1.82 | 7.27 | 1.78 | 1.65 | 7.07 | 6.94 | 6.49 | 6.46 |

| 4 | 2.18 | 2.03 | 6.73 | 1.99 | 1.86 | 6.78 | 7.72 | 6.37 | 17.51 |

| 5 | 2.17 | 1.80 | 16.94 | 1.93 | 1.67 | 13.70 | 9.24 | 6.59 | 28.67 |

| 6 | 2.51 | 1.85 | 26.29 | 2.02 | 1.63 | 19.28 | 15.10 | 7.01 | 53.56 |

| 7 | 3.00 | 2.56 | 14.55 | 2.61 | 2.10 | 19.72 | 16.10 | 12.92 | 19.75 |

| 8 | 2.50 | 1.84 | 26.52 | 2.02 | 1.54 | 24.00 | 10.32 | 7.92 | 23.22 |

| 9 | 2.22 | 2.02 | 9.18 | 1.97 | 1.79 | 9.05 | 12.64 | 9.91 | 21.59 |

| 10 | 2.82 | 2.33 | 17.34 | 2.48 | 2.21 | 11.07 | 10.29 | 7.84 | 23.77 |

| 11 | 4.22 | 4.22 | −0.09 | 2.70 | 2.80 | −3.67 | 19.88 | 18.40 | 7.46 |

| 12 | 2.40 | 2.12 | 11.60 | 2.13 | 1.96 | 7.86 | 9.07 | 8.86 | 2.37 |

| 13 | 2.05 | 1.77 | 13.64 | 1.78 | 1.57 | 11.92 | 8.65 | 8.38 | 3.09 |

| 14 | 2.04 | 1.72 | 15.58 | 1.66 | 1.45 | 12.78 | 10.79 | 8.35 | 22.66 |

| 15 | 3.02 | 2.64 | 12.60 | 2.64 | 2.28 | 13.69 | 15.93 | 12.79 | 19.70 |

| Mean | 2.60 | 2.26 | 13.55 | 2.18 | 1.92 | 11.95 | 12.09 | 9.59 | 19.53 |

Figure 4.

Cumulative distributions for the surface errors for each volume, with the x axis showing a distance error and the y axis showing the percentage of points for which the error is smaller than this distance.

The slice thickness in the volumes used in this study is 3 mm. One observes that the model-based approach leads to results with more than 90% of the surface points having a distance error less than 4 mm, which is on the order of one voxel in the axial direction, for all cases except cases 2, 7, 11, and 15. The model-based approach leads to substantial improvements for cases 1, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, and 14. For cases 3, 4, and 9, the 90% threshold was reached with the atlas-based approach alone. A closer look at patient 2 (see Fig. 5) shows errors at levels II–IV. At level II, the manual contour was drawn smaller than the contour produced by our algorithm. Retrospective discussions with the radiation oncologists determined that the observed difference was within the inter-rater variability. At level III, a reactive but not pathological enlarged node occupies the place normally occupied by interstitial fat, which has a lower intensity than other tissues in CT images. The automatic contour includes the node when it is excluded in the manual contour. Again, retrospective discussion with the radiation oncologists determined that both were acceptable and a function of the physician’s preferences. The error at level IV is caused by the size of the thyroid, which is smaller than usual. The main segmentation error for patient 7 occurred at level IV. This subject has a thyroid that is much larger than usual and the contrast between the thyroid and the surrounding tissues is low. As a consequence, the registration was inaccurate, the model was initialized incorrectly, and the ASM component of the system became trapped in a local minimum.

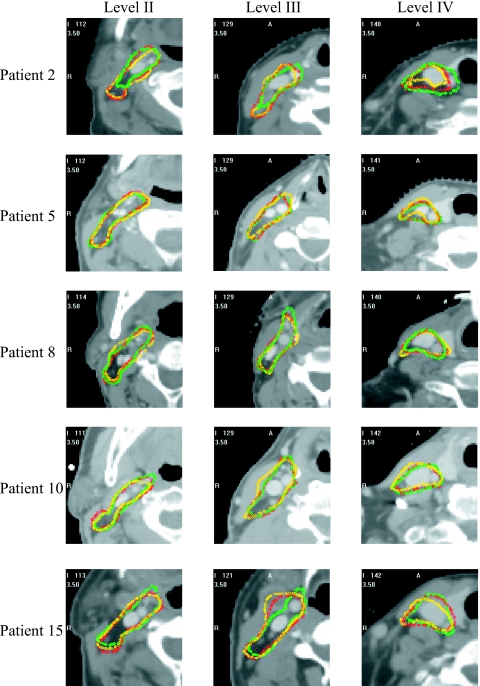

Figure 5.

2D contours for the manual, atlas-based, and ASM-based segmentations for patients 2, 5, 8, 10, and 15. Shown from the left to the right are contours in level II–IV regions; the manual contour is in green, the atlas-based in yellow, and the ASM-based in red.

In patient 15 (see Fig. 5), the largest error was at the end of level II toward level III. At this place, a large node infiltrated by metastatic cancer was visible. This also produced registration and initialization errors that could not be recovered. Retrospective discussion with the radiation oncologists established that this area should have been treated with a higher dose and not part of a prophylactic regimen. A substantial error was also visible at level IV because of an enlarged thyroid.

Figure 5 shows contours superimposed on the images for five subjects. In each case, one representative slice per level has been chosen. The green, yellow, and red contours are the manual, atlas-based, and model-based contours, respectively. This figure confirms what is shown in Fig. 5. Subjects 5, 8, and 10 are cases for which the cumulative distributions show a clear improvement. For these three subjects, the red contours are indeed closer to the green contours than the yellow ones. For subjects 2 and 15, the cumulative distributions do not show a substantial difference between the two approaches. In these two cases, the model could not compensate for registration errors caused by abnormal anatomy.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We have developed a method for the segmentation of normal-looking lymph nodes in clinically acquired head and neck CT scans that improves upon atlas-based approaches, which have been proposed to solve this problem. As discussed in the background section, prophylactic treatment of normal-looking lymph nodes is within the standard practice for many head and neck cancers, and their delineation is a time-consuming process. Reliable methods designed for their automatic segmentation may thus have a substantial impact on the daily clinical load. Previously, we had used a single model for all three node levels (see Ref. 15). This approach led to mixed results, i.e., in some cases the model-based approach led to better results, while in others it did not. Separating the model into three models, one for each level, improved the results. As reported in this study, the model-based approach now leads to better results than a purely atlas-based method in all cases with normal-looking anatomy. In all these cases, more than 90% of the surface points have a distance error of less than 4 mm, which is on the order of one voxel in the axial direction.

Comparison to other studies is difficult not only because the data sets are different but also the evaluation methods vary among studies. In the work of Gorthi et al.4 CT images are of similar size (0.9375 mm×0.9375 mm×3 mm) and the sensitivity, DSC, and Hausdorff distance are reported. In their leave-one-out experiment, the mean DSC reported for levels IIA, IIB, III, and IV are 0.53, 0.46, 0.43, and 0.36, respectively, while the mean DSC for our ASM-based segmentation is 0.698 for levels II–IV segmented as a single structure. The mean Hausdorff distances that are reported are 14.52, 15.06, 18.68, and 21.81 mm for levels IIA, IIB, III, and IV. The comparable average maximum distance error is 9.59 mm for our ASM-based approach. In a similar work, Commowick et al.3 reported a mean sensitivity of 0.692, a specificity of 0.813, and a combined error of 0.360. However, sensitivity and specificity numbers are difficult to interpret for segmentation tasks. Indeed, sensitivity is defined as TP∕(TP+FN) and specificity as TN∕(TN+FP), where true positive (TP) is the number of voxels included in both the manual and the automatic contours, true negative (TN) is the number of voxels excluded by both methods, false positive (FP) is the number of voxels in the automatic segmentation but not in the manual segmentation, and false negative (FN) is the number of voxels in the manual segmentation but not in the automatic segmentation. Sensitivity and specificity need to be reported together because the former does not measure oversegmentation and the latter does not measure undersegmentation. In addition, the definition of the specificity involves TN, which for segmentation tasks is the intersection of the manual and automatic background regions. These can be made arbitrarily large, thus leading to large specificity values and requiring heuristic criteria to define TN, as discussed in Ref. 16.

The results we have presented also show shortcomings of the current approach. Abnormal anatomy and∕or pathology (cases 2, 7, 11, and 15) lead to poorer results mainly because inaccuracy in the registration results in poor initialization of the model. While one may expect increased robustness to anatomical variations with larger training sets, segmenting volumes with large pathologies is more challenging and will, in all likelihood, require different strategies. One possibility is to use a mixed approach in which the pathology is delineated by hand first and then used as constraint to guide the segmentation process. Based on our observation, the thyroid region remains challenging because of large variations in the shape and size of this organ. Reducing the sensitivity of our approach to initialization errors may be possible by modifying the algorithm that is used to update the boundary points. For instance, Van Ginneken et al.17 proposed a technique in which optimal features are selected for each landmark using a kNN-classifier. Toth et al.18 also proposed a method in which an optimal weighted average of texture features is used to establish correspondence. Using neighborhood information, as proposed by these authors, instead of line information may permit the algorithm to escape from local minima. Whether or not these improvements are able to compensate for inaccuracy in the registration process caused by anatomical variations will need to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported, in part, by NIH Grant No. R01EB006193 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these institutions. The authors acknowledge Vanderbilt’s Department of Radiation Oncology for providing the CT images for the study. They also acknowledge Jack H. Noble and Ryan D. Datteri for their valuable suggestions on the construction of the ASM. An earlier version of this work has been presented at the 2010 SPIE Conference on Medical Imaging (Ref. 15).

References

- Chao K. S. et al. , “Reduce in variation and improve efficiency of target volume delineation by a computer-assisted system using a deformable image registration approach,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 68, 1512–1521 (2007). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commowick O., Grégoire V., and Malandain G., “Atlas-based delineation of lymph node levels in head and neck computed tomography images,” Radiother. Oncol. 87, 281–289 (2008). 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commowick O., Warfield S. K., and Malandain G., “Using Frankenstein’s creature paradigm to build a patient specific atlas,” Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI ‘09), Vol. 5762, Pt. II, pp. 993–1000, September 2009. (unpublished). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gorthi S., Duay V., Houhou N., Cuadra M. B., Schick U., Becker M., Allal A. S., and Thiran J. P., “Segmentation of head and neck lymph node regions for radiotherapy planning using active contour-based atlas registration,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 3, 135–147 (2009). 10.1109/JSTSP.2008.2011104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cootes T. F., Taylor C. J., Cooper C. H., and Graham J., “Active shape models-their training and application,” Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 61, 38–59 (1995). 10.1006/cviu.1995.1004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frangi A. F., Rueckert D., Schnabel J. A., and Niessen W. J., “Automatic construction of multiple-object three-dimensional statistical shape models: Application to cardiac modeling,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 21, 1151–1166 (2002). 10.1109/TMI.2002.804426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cootes T. F., Hill A., Taylor C. J., and Haslam J., “The use of active shape models for locating structures in medical images,” Image Vis. Comput. 12, 276–285 (1994). 10.1016/0262-8856(94)90060-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ausili Cefaro G., Perez C. A., Genovesi D., and Vinciguerra A., A Guide for Delineation of Lymph Nodal Clinical Target Volumes in Radiation Therapy (Springer, New York, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Guimond A. D., Meunier J., and Thirion J. P., “Average brain models: A convergence study,” Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 77, 192–210 (2000). 10.1006/cviu.1999.0815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Studholme C., Hill D. L. G., and Hawkes D. J., “An overlap invariant entropy measure of 3D medical image alignment,” Pattern Recogn. 32, 71–86 (1999). 10.1016/S0031-3203(98)00091-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde G. K., Aldroubi A., and Dawant B. M., “The adaptive bases algorithm for intensity-based nonrigid image registration,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 22, 1470–1479 (2003). 10.1109/TMI.2003.819299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., “Compactly supported positive definite radial functions,” Adv. Comput. Math. 4, 283–292 (1995). 10.1007/BF03177517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Insight Segmentation and Registration Toolkit, http://www.itk.org/.

- Dice L. R., “Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species,” Ecology 26, 297–302 (1945). 10.2307/1932409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., Deeley M. A., Niermann K. J., Moretti L. D., and Dawant B. M., “Segmentation of lymph node regions in head-and-neck CT images using a combination of registration and active shape model,” Proceedings of SPIE Medical Imaging, Vol. 7623, p. 76231Q, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Isambert A. et al. , “Evaluation of an atlas-based automatic segmentation software for the delineation of brain organs at risk in a radiation therapy clinical context,” Radiother. Oncol. 87, 93–99 (2008). 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ginneken B. et al. , “Active shape model segmentation with optimal features,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 21, 924–933 (2002). 10.1109/TMI.2002.803121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth R.et al. , “WERITAS–Weighted ensemble of regional image textures for ASM segmentation,” Proceedings of SPIE Medical Imaging, pp. 725905, 2009.