Abstract

Sumoylation is a covalent modification, which is mediated by small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) polypeptides. A growing body of evidence has shown that sumoylation affects the functional properties of many substrates in the regulation of cellular processes. Recent reports indicate the critical role of sumoylation in human diseases including familial dilated cardiomyopathy, suggesting that targeting of sumoylation would be of considerable interest for novel therapies. Even though hundreds of SUMO substrates have been identified, their pathophysiological roles remain to be determined. Among them, ERK5-sumoylation has recently been linked to diabetes and implicated in endothelial dysfunction and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo. These findings support the idea that ERK5-sumoylation is a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of diabetes-related cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: SUMO, sumoylation, ERK5, diabetes, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) covalently attaches to certain residues of specific target proteins and alters a number of different functions depending on the substrates. Sumoylation counteracts ubiquitination and subsequent proteosomal degradation via competition with the same lysine residue of substrates [1,2]. In addition to a decoy mechanism of sumoylation in the ubiquitin-proteasome system, sumoylation is involved in most cellular functions including subcellular localization, DNA-binding and/or transactivation of transcription factors [3,4]. Recent reports indicate that regulation of sumo-conjugation contributes to the pathogenesis and development of cardiovascular complications [5–8]. The purpose of this review is to summarize the physiological role of sumoylation-related molecules in the cardiovascular system, the pathological role of ERK5-sumoylation in diabetes-related cardiovascular diseases, and its therapeutic potential.

Sumoylation process

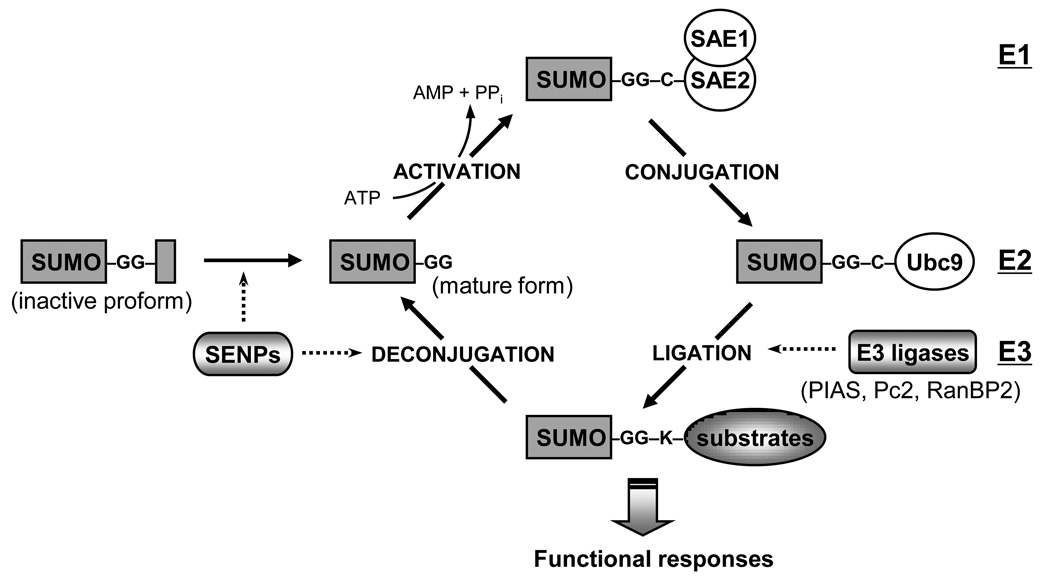

Sumoylation is a dynamic and reversible process that is regulated by both conjugation and deconjugation pathways (Figure 1). The regulatory mechanism is analogous to ubiquitin-conjugation system, but sumoylation is regulated by a different set of enzymes. Most enzymes are evolutionary conserved from yeast to humans. To conjugate SUMO to the substrates, the proform of SUMO needs to be cleaved by sentrin/SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs) that hydrolyse C-terminal end to expose Gly-Gly motif [9]. SENP has not only a hydrolase activity but also an isopeptidase activity, which regulates deconjugation of sumoylated substrates [9,10]. The mature form of SUMO is activated in an ATP-dependent manner by an E1-activating enzyme, which consists of an SAE1-SAE2 heterodimer [11]. Activated SUMO is transferred to Ubc9 (E2 conjugase) to form a thioester bond and is subsequently attached to the e-amino group of a lysine residue in the target substrates [12]. Even though Ubc9 itself associates with SUMO and transfers SUMO to targets, specific SUMO E3 ligases are required for efficient modification. Several classes of SUMO ligases have been identified: the family of protein inhibitor of activated STAT (PIAS; PIAS1, PIAS2(x), PIAS3, PIAS4(y)), Polycomb-2 protein (Pc2), and RanBP2/Nup358, a component of the nuclear pore complex. Since E1 and E2 enzyme are limited in number, it has been considered that E3 ligases and SENPs are responsible targets for fine-tuning the specific regulatory pathway of SUMO substrates.

Figure 1. The regulation of sumoylation pathway.

Protein sumoylation is achieved by the recycle system consisting conjugation and deconjugation pathway. SUMO conjugation to target substrates requires an enzymatic cascade that involves three classes of enymes (E1→E2→E3). The sentrin/SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs) are responsible for the deconjugation pathway as well as the maturation process of newly synthesized SUMO proteins.

Roles of sumoylation-related molecules in cardiovascular system SUMO

In contrast to yeast and non-vertebrates, the mammalian genome contains multiple SUMO genes (Table 1). The sequence identity between SUMO1 and SUMO2 is about 46%, but the mature form of SUMO2 and SUMO3 are nearly identical [13,14]. Multiple proteomic screenings of SUMO substrates showed that each gene is conjugated to different target proteins, suggesting the distinct features in substrate specificity [15,16]. It has been suggested that different localization of each gene might explain the substrate specificity (Table 1). SUMO1 is mainly conjugated to substrates in vivo, whereas a majority of SUMO2/3 exist as free forms and respond to stress stimuli such as oxidative stress and heat shock [17].

Table 1.

| Modifier | % of identity (vs SUMO2) |

Cellular localization | Tissue distribution |

Phenotypic effects of genetic mutation | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUMO1 | 100 | NM >> NB ≈ C | ubiquitous | SUMO1−/− no developmental defect | [22•,23] |

| Haploinsufficiency and human SNP : cleft lip and palate | [24,25] | ||||

| SUMO2 | 46.1 (100) | NB >> C > NM | ubiquitous | ND | |

| SUMO3 | 45.0 (87.5) | C > NB > NM | ubiquitous | ND | |

| SUMO4 | 41.0 (85.3) | ND | kidney, spleen, lymph node | Human SNP (SUMO4-M55V) : susceptibility to Type 1 diabetes | [27••,29] |

NM: nuclear membrane; NB: nuclear bodies; C: cytosol, ND: not determined.

One of the interesting differences between SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 is the ability of SUMO2/3 but not SUMO1 to form polymeric chains. Tatham et al. have reported that only SUMO2/3, but not SUMO1, can form isopeptide bonds between the C-terminal glycine residue of one SUMO molecules and Lys 11 of another molecule of SUMO2/3, and lead to poly-sumoylation [18]. Interestingly, it has been reported that the functional consequence of poly- and monosumoylation might be different. Especially, the RING domain-containing ubiquitin E3 ligase, RNF4, only targets poly-SUMO-mediated proteins for degradation mediated by ubiquitin [19–21]. Therefore, since only SUMO2/3 can form polymeric chains, SUMO2/3-targeted substrates may have more chances to be ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded.

The functional roles of sumoylation in mammals are limited to SUMO1 because data of other gene knockouts is not available. Given the fact that SUMO1−/− mice show no developmental defect, SUMO2/3 might be able to compensate for SUMO1 deficiency [22,23]. However, another group showed that haploinsufficiency of SUMO1 is related to the development of cleft lip and palate via Eya1-sumoylation in part [24,25]. Shao and co-workers reported that hypoxia could increase SUMO-1 expression and HIF1α-sumoylation in mice hearts [26]. It is therefore interesting to investigate if SUMO1 deficiency affects cardiac dysfunction after ischemic injury via HIF-1α regulation in SUMO1−/− mice. We will discuss the role of HIF1α-sumoylation later in this review.

The human genome encodes a unique modifier of SUMO4, which is mainly expressed in the kidney, lymph node and spleen [27]. Genetic mutation of SUMO4 at Met 55 has been discovered and human study showed that SUMO4-M55V mutation is correlated to type 1 diabetes [27–29]. Guo et al. found that SUMO4-M55V mutation increased TNFα-induced nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation compared with wild type and proinflammatory IL12B expression is significantly higher in peripheral blood monocytes from individuals carrying SUMO4-M55V than in control individuals, suggesting the susceptibility for inflammation of SUMO4-M55V substitution [27]. The detailed mechanisms of SUMO4 were suggested by the transcriptional regulation of several transcription factors. For example, SUMO4 negatively regulates NF-κB transcriptional activity via IκBα-sumoylation, leading to inhibit its ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis and stabilize IκBα [30,31]. It has been reported that the transcriptional activity of heat shock factor and activating protein-1 are also affected by SUMO4 [28,29], but the exact implications of SUMO4 sumoylation of two transcription factors in terms of susceptibility to type 1 diabetes remain to be determined.

Lamin A polymorphism associated with sumoylation in familial dilated cardiomyopathy

Aside from single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of SUMO4 gene, substitution of lamin A at Glu 203 (E203) has been identified [32,33]. Lamin A plays an important role in nuclear architecture and its mutations are involved in many human diseases, including familial dilated cardiomyopathy (FDC) and muscular dystrophies [34,35]. Recently Zhang and Sarge reported that Lys 201 is a specific target site of lamin A-sumoylation and sumoylation defective mutant (K201R) reveals abnormal nuclear localization, suggesting the critical role of sumoylation in nuclear function of lamin A [6]. Interestingly they found that two different SNPs of lamin A related with FDC, E203G and E203K, have a defect in lamin A-sumoylation. Since glutamic acid is also important for the SUMO-conjugation to the target lysine in the classical consensus sequence [31] (ψKxE/D; ψ represent a bulky hydrophobic residue and E/D represent an acidic residue), it is possible that E203 is involved in SUMO-conjugation at K201 residue in 200-MKEE-203 consensus sequence of lamin A. Furthermore they provide clinical relevance with patient fibroblasts, which showed abnormal lamin A localization and nuclear morphology similar to cells expressing lamin A-K201R, -E203G, and -E203K mutants [6]. These findings provide a molecular insight of pathogenesis of lamin A-related FDC, indicating that sumoylation has a significant impact on cardiomyopathy in vivo.

Ubc9 (E2)

Ubc9 is the single E2 conjugase for sumoylation process. The physiological roles of sumoylation in mammals have been addressed in mice deficient for Ubc9 E2 conjugase [36]. Homozygous Ubc9 deficiency reveals embryonic lethality due to the developmental defect at the early postimplantation stage. Ubc9-deficient blastocysts showed severe abnormality in nuclear organization, chromosome segregation, PML nuclear bodies and RanBP2-dependent nuclear pore complex, suggesting that most SUMO substrates are nuclear proteins and involved in cellular viability. Since Ubc9 itself conjugates SUMO to substrates, it is intriguing how Ubc9 regulates some of substrates without distinct E3 ligases.

E3 ligase

E3 ligases have a tuning function at the last step of sumoylation process [37]. In contrast to single E1 and E2 enzymes, many of E3 ligases have been identified. Mammalian PIAS (The protein inhibitor of activated STAT) family is a major SUMO E3 ligase, which consists of PIAS1, PIAS2 (PIASx), PIAS3, and PIAS4 (PIASy). In addition to PIAS family, RanBP2 and Pc2 have been identified as other types of SUMO E3 ligases. In this review we will focus on the role of PIAS1 and PIAS4 because both knock out mice were relatively well studied, as we will discuss below (Table 2).

Table 2.

| Modulator | Classification | Phenotypic effects of genetic mutation | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIAS1 | E3 ligase | Systemic PIAS1−/− susceptible against viral and microviral infection, high level of NF-κB and STAT1 transcriptional activity | [40] |

| PIAS4 | E3 ligase | Systemic PIAS4−/− no developmental defect, susceptible against septic-shock | [41 ,43•] |

| SENP1 | deconjugase | Systemic SENP1−/− embryonic lethal and defect in erythropoiesis | [52,53•] |

| SENP2 | deconjugase | Systemic SENP2−/− embryonic lethal and defect in cell cycle G1-S transition | [54•] |

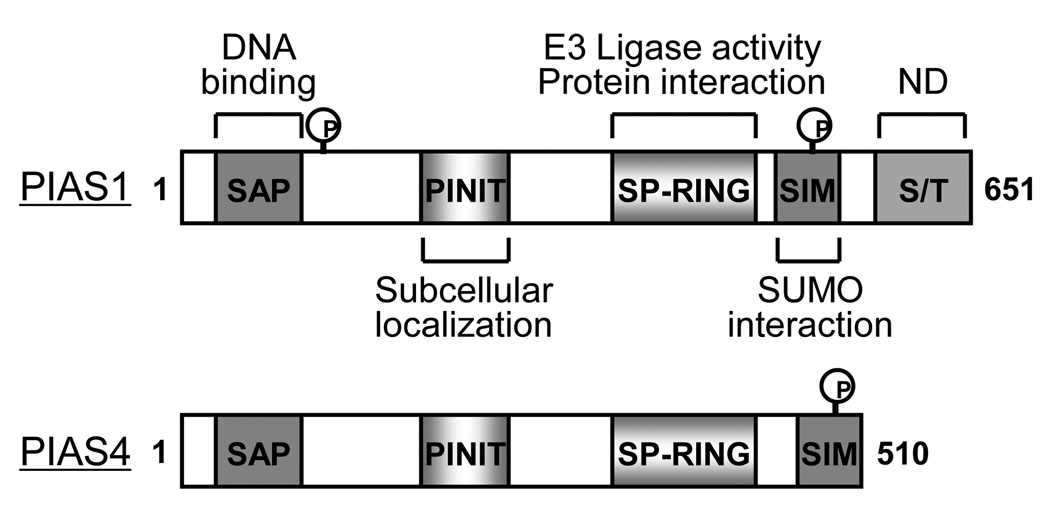

PIAS1 was originally identified as a transcriptional repressor of STAT1 and NF-κB by blocking the DNA-binding activity to specific promoters with SAP (scaffold attachment factor-A/B, acinus and PIAS) domain [38]. Later it turned out that PIAS family proteins have SUMO ligase activity characterized by an SP-RING domain, which is similar to that of ubiquitin E3 ligases [39]. Besides SAP and SP-RING domains three other conserved domains of PIASs are detected; 1) PINIT domain, which regulates nuclear retention of PIAS family, 2) AD (highly acidic domain) or SIM (SUMO-interacting motif) domain, which is the SUMO binding domain, and 3) the Ser/Thr rich region (Figure 2). PIAS1 null mice showed high level of STAT1 and NF-κB activity, and were susceptible to viral and microbial infections [40]. However, the role of PIAS1 as the SUMO E3 ligase and its functional target in vivo remains unclear. Gene targeting mice in PIAS4 have no distinct phenotype and have a modest reduction in interferon and Wnt signaling compared to non-transgenic littermate control mice (NLC) [41]. However, another group reported that there are no significant changes in terms of interferon signaling [42]. It is possible that different methods for gene targeting may cause the functional difference. Interestingly, Tahk and colleagues found that the survival rate after lipopolysaccharide injection is significantly reduced in the same line of PIASy−/− mice, indicating a specific response to cellular stress [43]. They also found that despite the mild phenotypes of single null mice, double transgenic mice (PIAS1−/−/PIASy−/−) are embryonic lethal. These results support the idea that PIAS family proteins have functional crosstalk with each other in the physiological condition.

Figure 2. Primary domain structure of PIAS1 and PIAS4.

PIAS family proteins have unique SP-RING domain which execute sumoylation by enzymatic process. N-terminus of PIAS1 can be phosphorylated by IKKα and this modification regulates NF-κB transrepression while PIAS4 does not have a conserved phosphorylation site although PIAS4 also has function of transrepression for NF-κB transcriptional activity. C-terminus of PIAS family has CK2-mediated phosphorylation site which resulted in the increased SUMO-binding affinity. Other regions are not fully characterized yet.

SAP: scaffold attachment factor-A/B, acinus and PIAS; SP-RING: Siz/PIAS-RING domain; SIM: SUMO interacting module; S/T: serine/threonine rich region; ND: not determined.

The biochemical studies using mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from PIAS4−/− mice demonstrated that PIAS4 regulates cellular senescence and apoptosis in a p53-dependent manner [44]. They found that overexpression of PIAS4, but not other PIAS proteins, stimulates cellular senescence and apoptosis by p53-sumoylation and oncogenic RAS-induced senescence is reduced in PIAS4−/− MEFs. In general p53 is a key regulator of cell death through its transcriptional activation. However, emerging evidence showed the transcription-independent role of p53 in apoptosis via p53-BCL2 binding, which leads to inhibition of BCL2 function in mitochondrial membrane integrity [45]. Recently we found that PKCζ-PIAS4 signal nodule induces p53-sumoylation-dependent nuclear export, p53-BCL2 binding, and subsequent apoptosis in endothelial cells (ECs) (KS Heo et al., unpublished). Further work will be necessary to prove the importance of PIAS4 and p53-sumoylation in atherosclerosis with PIAS4−/− mice.

E3 ligases are key regulators for sumoylation and functional consequences in vivo. However, what is lacking is the molecular mechanism how ligase activity is regulated in physiological condition. IKKα-dependent phosphorylation site of PIAS1 has been identified at Ser 90 and this modification plays a role in the negative regulation of NF-κB through repression [46]. TNFα-induced NF-κB activation was enhanced in PIAS1 phosphorylation mutant and this mutant lost the binding affinity to NF-κB promoter. Another group reported that PIAS1-mediated PPARγ-sumoylation has an anti-inflammatory effect in monocytes/macrophages via the transrepression of NF-κB promoter activity [47]. These data support the potential implication of PIAS1 modulator as therapeutic interventions in inflammation-related cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis. Recently, Stehmeier et al. suggested a novel mechanism that casein kinase 2 (CK2)-mediated phosphorylation of PIAS1/3 increased its binding affinity to SUMO and SUMO substrates, suggesting that kinase-mediated signal cascade may govern PIAS ligase activity to specific substrates [48]. Since CK2 has been recognized as a therapeutic target of cardiac hypertrophy [49], it would be interesting to identify the specific substrates of CK2-PIAS module-mediated sumoylation in cardiac hypertrophy.

SENPs

SUMO conjugation occurs through an enzymatic cascade, but this reaction is reversible in the process regulated by SENP. The hydrolytic activity of SENP is regulated by well-conserved C-terminus catalytic domain, but N-terminus is poorly conserved, suggesting the regulatory role of this region [9,50]. Li and colleagues showed that TNFα transiently induced SENP1 translocation from cytosol to nucleus and subsequently resulted in JNK activation and apoptosis through HIPK2-desumoylation in endothelial cells, indicating the dynamic regulation of desumoylation process in response to extracellular stimuli [51]. It has been intensively studied how SENP recognizes the specific substrates, but the molecular mechanism and physiological role of SENP regulation remain to be established. Among 7 isoforms, the functions of SENP1 and SENP2 were studied most using genetic mutations in mouse. The physiological role of SENP1 was addressed with a loss of function study by a retroviral insertional mutation of mouse SENP1 [52]. The mutant mice revealed placental defects with widespread cell death and led to death between e12.5 and e14.5. Recently another group observed a similar phenotype regarding embryonic lethality in SENP1−/− mice and suggested the molecular insight that SENP1 is critical for stabilization of HIF-1α during hypoxia.

At normoxic condition, HIF1α is hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) proteins, which leads to the interaction with ubiquitin ligase von Hippel Lindau protein (VHL). VHL mediates poly-ubiquitination and degradation of HIF1α and inhibits its activity. Under the hypoxic condition, PHD activity is inhibited and HIF1α is stabilized by the inhibition of the interaction of VHL and HIF1α. Interestingly, Cheng et al. have reported that hypoxia induced HIF1α -sumoylation, and VHL recognizes not only hydroxylation but also this sumoylation form of HIF1α and ubiquitinates/degradates it. Therefore, to make HIF1α stabilized under hypoxia, de-sumoylation enzyme SENP1 becomes critical. SENP1 de-sumoylates HIF1α and inhibits VHL-HIF1α interaction and stabilizes it [53]. HIF1α is a master transcriptional factor to regulate erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, and glucose metabolism, especially under hypoxia. Therefore, it is very reasonable that SENP1−/− embryos showed severe fetal anemia stemming from deficient erythropoietin production. The interplay between hydroxylation and sumoylation of HIF1α remains unclear. It is also intriguing to point out that hypoxia-mediated HIF-1α stabilization is not affected in SENP2−/− MEFs, indicating the substrate specificity between SENP1 and SENP2 although it is hard to distinguish the deconjugation activity in vitro.

Recently, Chiu et al. have reported that SENP2 is critical in development of trophoblast layers [54]. SENP2 knock out mice showed a defect in the cell cycle G1-S transition during placentation. The authors found a significant increase of Mdm2-sumoylation in SENP2 knock out mice. The sumoylation of Mdm2, which is a ubiquitin E3 ligase of p53, inhibited Mdm2 ubuquitin ligase activity, stabilized p53, inhibited DNA synthesis and trophoblast development [55]. Since both SENP1−/− and SENP2−/− die midgestation, the functional role of SENP remains largely unknown in adult organs including the heart tissue.

ERK5-sumoylation in cardiovascular diseases

Atherosclerosis, the primary cause of heart failure and stroke, is one of the most global burdens for human health care today. Epidemiological studies over the past decade have revealed that diabetes significantly affects this process via EC inflammation. Inflammation is regarded as an important initiating factor in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and its cardiovascular complications, and anti-inflammatory therapy has gained increasing attention in the drug development of cardiovascular diseases [56]. There is a lot of evidence showing that diabetic stimuli activate proinflammatory signaling pathways, while little is known about diabetes-mediated inhibition of anti-inflammatory responses. Our lab reported that steady laminar flow stimulation of PPARγ1 activity, via activation of ERK5, contributes to the anti-inflammatory and atheroprotective effects of flow [57]. However, the molecular mechanism of the role of ERK5 in diabetes-mediated inflammatory responses remains largely unknown. Recently, we found that diabetic stimuli can inhibit ERK5 transcriptional activation through ERK5-sumoylation [7]. Here we will discuss the novel mechanism of diabetes-induced ERK5-sumoylation in the cardiovascular system, which may explain the causal relationship between diabetes and EC inflammation as well as exacerbation of cardiac dysfunction in diabetic heart.

ERK5 in Diabetes: ERK5-sumoylation

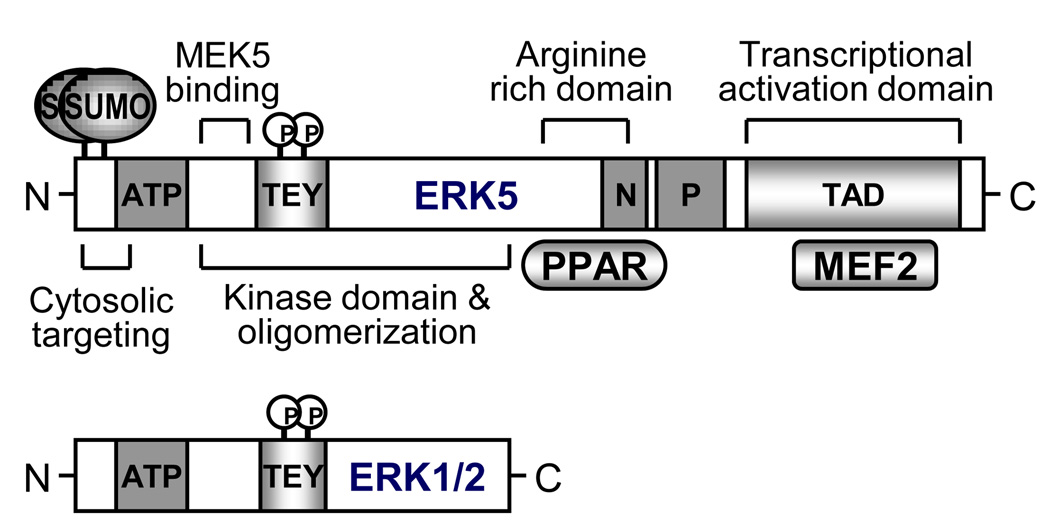

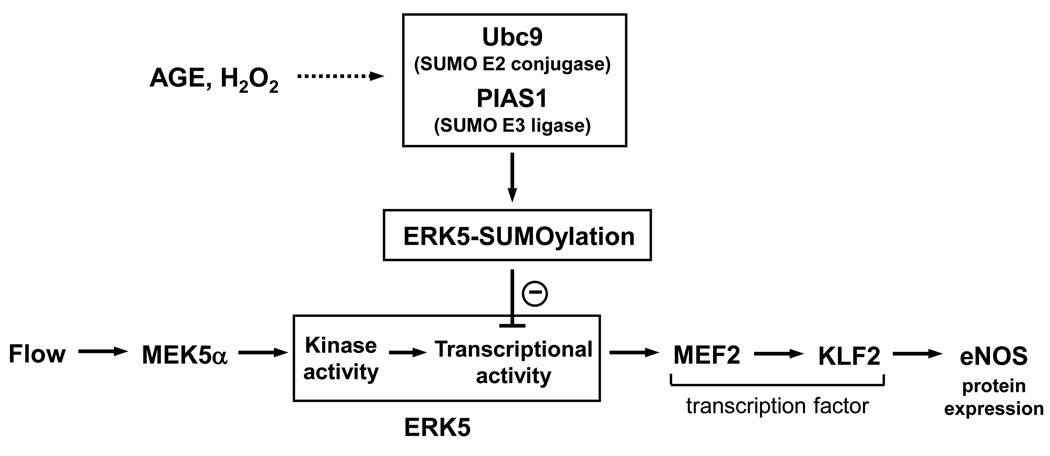

ERK5 has dual phosphorylation sites, like ERK1/2, containing TEY motif that are phosphorylated by the upstream kinase, MEK5 (Figure 3). However, ERK5 is not only a kinase but also a transcriptional coactivator characterized with a unique C-terminal transactivation domain, suggesting that its regulation and function may be different from ERK1/2 (Figure 3) [58]. ERK5 null mice resulted in embryonic lethality, which was caused by blood leakage from the vessels due to endothelial apoptosis, indicating the essential role of ERK5 in endothelial survival [59]. Previously, our group found that steady laminar flow potently activates ERK5 [60] and flow inhibits leukocyte binding, as well as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression via ERK5 activation [61]. We have recently shown that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and advanced glycation end products (AGE) inhibit flow-induced ERK5 transcriptional activation as well as the subsequent KLF2 and eNOS expression via ERK5-sumoylation in ECs [7] (Figure 4). Interestingly, both stimuli increased ERK5 phosphorylation and kinase activity, suggesting the novel mechanism of kinase activity-independent regulation of ERK5 transcriptional activity. Lysine residues 6 and 22 of ERK5 have been identified as SUMO targeting sites. The inhibitory effect of H2O2 and AGE in ERK5 transcriptional activity is significantly reduced in the sumoylation-defect mutant form of ERK5 (ERK5-K6/22R) compared to wild type. In addition, depletion of PIAS1 and ERK5-K6/22R mutant reversed the inhibition of KLF2 and eNOS expression in response to diabetic stimuli. Furthermore we found that ERK5-sumoylation is increased in the aortic endothelial cells from diabetic mice. These data demonstrate that inhibition of ERK5-sumoylation might be a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of diabetes-related vascular diseases including atherosclerosis.

Figure 3. Primary domain structure of ERK5.

Instead of kinase domain which are similar to ERK1/2, ERK5 has long C-terminal region containing arginine rich domain, NLS, proline rich region, and transcriptional activation domain. These domains reveal unique features of ERK5 pathway including PPAR and MEF2. In particular the end of N-terminal region has sumoylation sites characterized by LKEE and VKAE in human.

N: nuclear localization signal; P: proline rich region; ATP: ATP binding domain; TEY: TEY phosphorylation motif.

Figure 4. A signaling scheme describing the relationship between laminar flow-mediated ERK5/MEF2/KLF2/eNOS pathway and H2O2 or AGE-mediated ERK5-SUMOylation.

It remains unclear how H2O2 and AGE induce ERK5-sumoylation. Several previous studies suggested that sumoylation could be regulated by crosstalk with other types of post-translational modifications including phosphorylation or association with binding partners that recruit sumoylation–related molecules. For example, phosphorylation-dependent sumoylation motif (PDSM: ψKxE/DxxS/TP) has been defined as a regulatory mechanism by which proline-directed kinase–mediated phosphorylation of serine residue in PDSM increases SUMO conjugation to target substrates [62,63]. However, we failed to find any PDSM in ERK5 sequence. There is another mechanism regulated by phosphorylation that phosphorylations of PIAS proteins alter target protein functions via either sumoylation-dependent or -independent manner [46,48]. Thus, it is interesting to identify the specific kinases that are activated in diabetes and phosphorylate sumoylation-linked enzymes.

ERK5-sumoylation increases myocyte apoptosis

Epidemiological studies strongly indicate that diabetes mellitus (DM) is an independent risk factor for both mortality and morbidity following myocardial infarction (MI) [64,65], especially since post-MI left ventricular (LV) function is significantly worse in diabetic patients. However, what is lacking is a plausible relationship between diabetes and any of the known regulators of myocyte apoptosis known to play a significant role in the post-MI cardiac dysfunction. Our group has demonstrated that down-regulation of phosphodiesterase 3A (PDE3A) is associated with apoptosis and induction of inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER), a proapoptotic transcriptional repressor, providing a mechanistic framework for how angiotensin II regulates myocyte apoptosis [66,67]. Sustained elevation of ICER favors apoptosis through inhibition of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB)-mediated transcription and down-regulation of Bcl-2 (Figure 5). Interactions between PDE3A and ICER constitute an auto regulatory positive feedback loop (PDE3A-ICER feedback loop) likely to determine the fate of injured myocytes (Figure 5). However, the mechanism between DM-mediated exacerbation of LV dysfunction and ERK5-mediated ICER reduction remains unknown. This question has been addressed with DM + MI model which was established by MI surgery one week after streptozotocin injection [8]. We found that streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia exacerbates LV dysfunction and mortality after MI [8]. In support of the idea that PDE3A-ICER cycle plays an important role in myocyte apoptosis and heart failure, we found a reduction of PDE3A and ICER induction in diabetic heart after MI. Since diabetic stimuli induced ERK5-sumoylation in ECs, it can be assumed that the level of ERK5-sumoylation is elevated in diabetic hearts after MI. Not surprisingly, ERK5-sumoylation was significantly increased in diabetic heart after MI and this induction is reversed with insulin treatment, suggesting the specific role of ERK5-sumoylation, but not the toxic effect of streptozotocin, on the exaggerated LV dysfunction and development of heart failure after MI in DM mice. Biochemical studies showed that oxidative stress and high glucose increase ERK5-sumoylation and decrease ERK5 transcriptional activity. We also found that H2O2-induced myocyte apoptosis is significantly inhibited in the presence of si-PIAS1 and adeno-viral vector expressing ERK5-K6/22R mutant compared to wild type. These results indicate that ERK5-sumoylation is a key modulation in myocyte apoptosis through ICER induction.

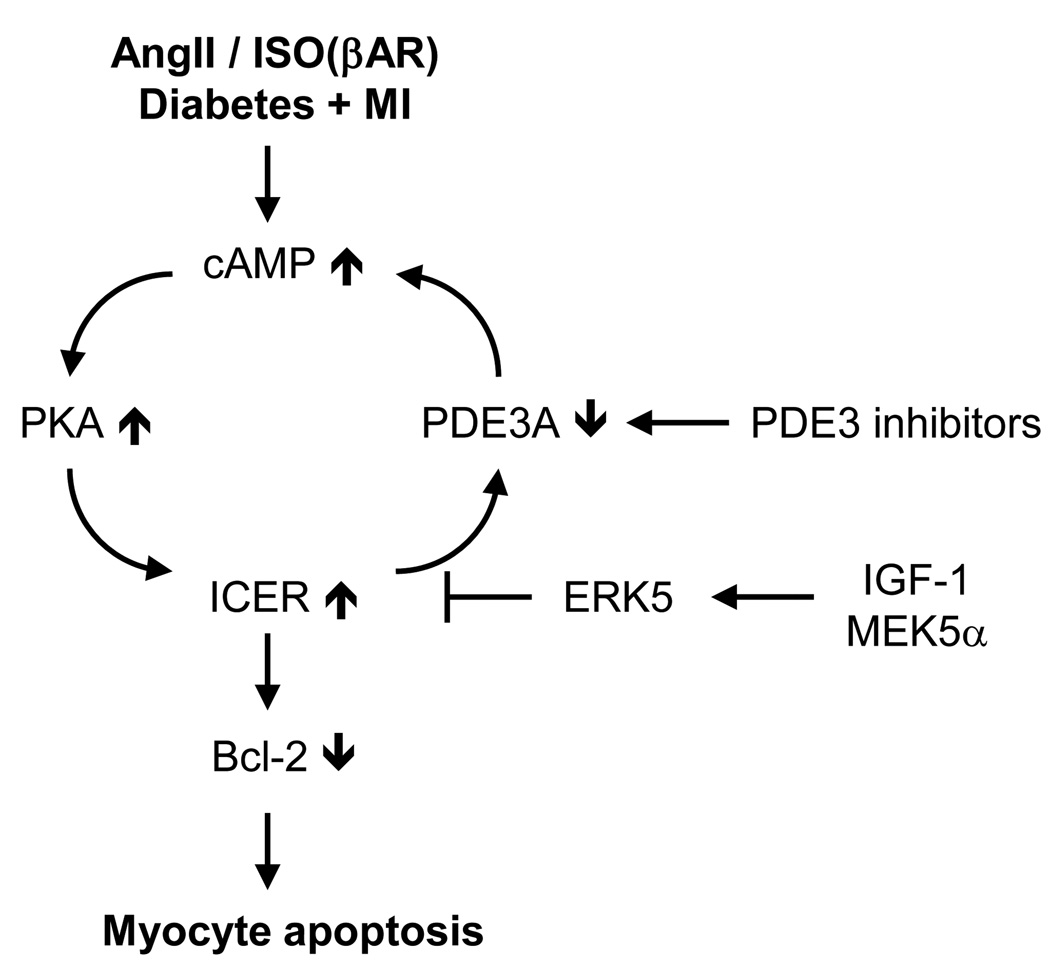

Figure 5. Schematic diagram of “PDE3A-ICER cycle” in myocyte apoptosis.

Angiotensin II, Isoproterenol (ISO), DM+MI mouse model and PDE3 inhibitors induce sustained down-regulation of PDE3A expression and up-regulation of ICER, which is regulated by PDE3A-ICER positive feedback loop. Persistent ICER elevation resulted in myocyte apoptosis via the inhibition of Bcl-2 which is an important anti-apoptotic regulator. IGF-1/MEK5-mediated ERK5 activation inhibits ICER induction through regulating ICER protein stability.

MEK5-ERK5 interaction protects cardiac dysfunction

It has been shown that ERK5 activation prevents MEF2-sumoylation via phosphorylation leading to an increase in its transcriptional activity [68]. Thus, we checked the effect of MEK5 activation in ERK5-sumoylation and found that CA-MEK5α inhibits sumoylation of both wild type as well as kinase dead mutant form of ERK5, suggesting the novel mechanism of MEK5 activation of ERK5 via reduction of ERK5-sumoylation which is not related to phosphorylation of TEY motif. The molecular basis has been proposed by two different ERK5 deletion mutants which lack the MEK5-ERK5 association sites. Even though both mutants were sumoylated, CA-MEK5α no longer inhibited sumoylation compared to wild type, indicating the critical role of MEK5-ERK5 association, but not ERK5 kinase activation, on MEK5 activation-mediated inhibition of ERK5-sumoylation. In agreement with in vitro data, we observed that ERK5-sumoylation, PDE3A-ICER cycle, and myocyte apoptosis was inhibited in CA-MEK5α-Tg mice compared with NLC. We also found that cardiac dysfunction and mortality in DM+MI mice was significantly improved in CA-MEK5α-Tg mice, suggesting the critical role of MEK5 activation in ameliorating the exacerbation of LV dysfunction in diabetic heart after MI. Taken together, our physiological data indicate that ERK5-sumoylation is significantly increased after ischemic injury and this induction may have an impact on the exacerbation of cardiac dysfunction and heart failure after MI in diabetic mice. Thus, a novel mechanism with the regulation of myocyte apoptosis via ERK5-sumoylation in diabetes may provide an important therapeutic target in diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Conclusions and perspectives

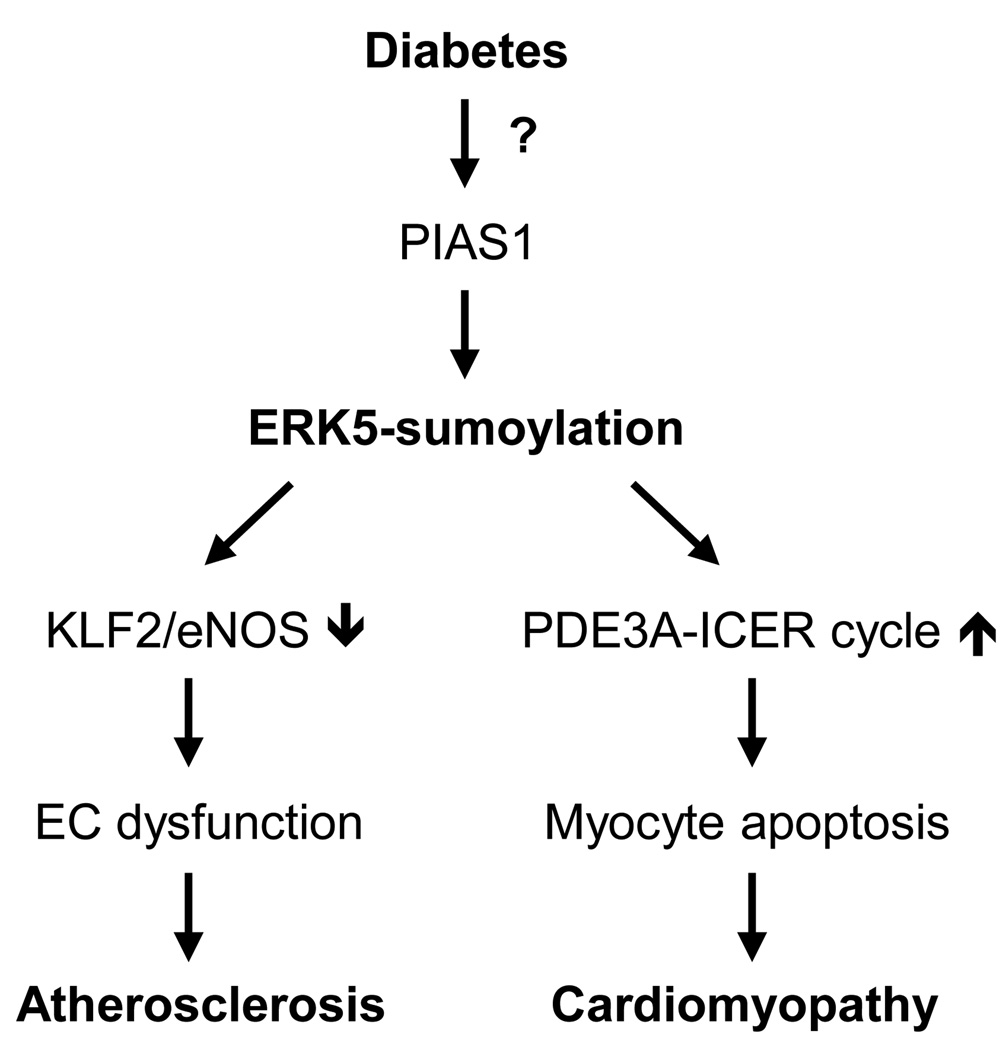

Although the molecular mechanism of sumoylation has been extremely well defined, the pathophysiological roles of sumoylation in vivo just begin to explore. Global knock down of sumoylation in Ubc9−/− mice demonstrated that sumoylation is a fatal post-translational modification for development and nuclear integrity. Specific genetic mutation analysis showed that PIAS proteins share substrates and can compensate for the deficiency of other genes in vivo. On the other hand some phenotypes shown in single gene knock out mice only appeared under the various challenges, indicating that each PIAS isoform has specific substrates and the pathological roles of PIAS proteins in cardiovascular diseases remain an open question. Also it is hard to define the pure roles of PIAS-mediated sumoylation with gene targeting technique due to the sumoylation-independent function of PIAS proteins such as DNA binding to promoters with SAP domain. In contrast to knock out model of PIAS proteins, both embryos from SENP1−/− and SENP2−/− mice died before/at midgestation. It can be assumed that SENP-mediated maturation of SUMO proforms plays a critical role in the developmental process or different isoforms have specific substrates that are fatal in cellular functions. However, relatively little is known about the detailed mechanism how SUMO E3 ligase and SENP activity is regulated in pathophysiological condition. Our recent data demonstrated that diabetic stimuli increase ERK5-sumoylation via PIAS1 leading to EC dysfunction and cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Figure 6). Several kinases have been known to be SUMO substrates including ERK5, HIPK2 and FAK although most SUMO substrates are restricted to nuclear proteins that function as transcriptional regulators. It is therefore intriguing whether sumoylation can interplay with kinase and sumoylation affects kinase activity. Particularly, studies using knock in system with sumoylation defective mutant forms of specific target molecules will provide the precise role of sumoylation in vivo.

Figure 6. Model of the role of ERK5-sumoylation in diabetes-related cardiovascular diseases.

Diabetic stimuli increase ERK5-sumoylation via PIAS1 regulation. In case of endothelial cells, ERK5-sumoylation down-regulates the expression of KLF2 as well as eNOS which are important in endothelial function. In addition ERK5-sumoylation induces cardiac apoptosis and dysfunction through PDE3A-ICER feed back loop.a

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association to Dr. Woo (Fellowship 0625957T, SDG 0930360N), and from the National Institute of Health to Dr. Abe (HL-088637, HL-064839, and HL-077789). Dr. Abe is a recipient of Established Investigator Awards of the AHA (0740013N).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Bergink S, Jentsch S. Principles of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications in DNA repair. Nature. 2009;458:461–467. doi: 10.1038/nature07963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoege C, Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature. 2002;419:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nature00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:947–956. doi: 10.1038/nrm2293. This review arthicle describes the general view of sumoylation process.

- 4.Hilgarth RS, Murphy LA, Skaggs HS, Wilkerson DC, Xing H, Sarge KD. Regulation and function of SUMO modification. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53899–53902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sarge KD, Park-Sarge OK. Sumoylation and human disease pathogenesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.01.004. Excellent review on the role of sumoylation in human diseases.

- 6. Zhang YQ, Sarge KD. Sumoylation regulates lamin A function and is lost in lamin A mutants associated with familial cardiomyopathies. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:35–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712124. First report of sumoylation-related cardiovascular diseases based on the human SNP of lamin A with familial dilated cardiomyopathies. The authors show that both lamin A SNPs (lamin A-E203G, -E203K) lose the ability of sumoylation. These mutations result in abnormal localization and nuclear function of lamin A.

- 7. Woo CH, Shishido T, McClain C, Lim JH, Li JD, Yang J, Yan C, Abe JI. Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 5 SUMOylation Antagonizes Shear Stress-Induced Antiinflammatory Response and Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression in Endothelial Cells. Circ Res. 2008 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156877. demonstrate that diabetic stimuli increase ERK5-sumoylation via PIAS1 modulation and this modification causes endothelial dysfunction via inhibition of KLF2/eNOS expression.

- 8. Shishido T, Woo CH, Ding B, McClain C, Molina CA, Yan C, Yang J, Abe J. Effects of MEK5/ERK5 association on small ubiquitin-related modification of ERK5: implications for diabetic ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2008;102:1416–1425. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168138. suggests that ERK5-sumoylation is a key modulation in diabetic cardiomyopathy via increasing myocyte apoptosis.

- 9.Yeh ET. SUMOylation and De-SUMOylation: wrestling with life's processes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8223–8227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li SJ, Hochstrasser M. A new protease required for cell-cycle progression in yeast. Nature. 1999;398:246–251. doi: 10.1038/18457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson ES, Schwienhorst I, Dohmen RJ, Blobel G. The ubiquitin-like protein Smt3p is activated for conjugation to other proteins by an Aos1p/Uba2p heterodimer. EMBO J. 1997;16:5509–5519. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson ES, Blobel G. Ubc9p is the conjugating enzyme for the ubiquitin-like protein Smt3p. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26799–26802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Su HL, Li SS. Molecular features of human ubiquitin-like SUMO genes and their encoded proteins. Gene. 2002;296:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00843-0. This paper describes the unique features of SUMO genes regarding sequence identity, cellular localization, and affinity to substrates so on.

- 14.Gill G. SUMO and ubiquitin in the nucleus: different functions, similar mechanisms? Genes Dev. 2004;18:2046–2059. doi: 10.1101/gad.1214604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosas-Acosta G, Russell WK, Deyrieux A, Russell DH, Wilson VG. A universal strategy for proteomic studies of SUMO and other ubiquitin-like modifiers. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:56–72. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400149-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedrioli PG, Raught B, Zhang XD, Rogers R, Aitchison J, Matunis M, Aebersold R. Automated identification of SUMOylation sites using mass spectrometry and SUMmOn pattern recognition software. Nat Methods. 2006;3:533–539. doi: 10.1038/nmeth891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saitoh H, Hinchey J. Functional heterogeneity of small ubiquitin-related protein modifiers SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2/3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6252–6258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tatham MH, Jaffray E, Vaughan OA, Desterro JM, Botting CH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35368–35374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uzunova K, Gottsche K, Miteva M, Weisshaar SR, Glanemann C, Schnellhardt M, Niessen M, Scheel H, Hofmann K, Johnson ES, et al. Ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic control of SUMO conjugates. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34167–34175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun H, Leverson JD, Hunter T. Conserved function of RNF4 family proteins in eukaryotes: targeting a ubiquitin ligase to SUMOylated proteins. EMBO J. 2007;26:4102–4112. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lallemand-Breitenbach V, Jeanne M, Benhenda S, Nasr R, Lei M, Peres L, Zhou J, Zhu J, Raught B, de The H. Arsenic degrades PML or PML-RARalpha through a SUMO-triggered RNF4/ubiquitin-mediated pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:547–555. doi: 10.1038/ncb1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang FP, Mikkonen L, Toppari J, Palvimo JJ, Thesleff I, Janne OA. Sumo-1 function is dispensable in normal mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5381–5390. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00651-08. This study along with Ref. [23] describes that SUMO1 deficiency can be compensated by SUMO2/3 in mice.

- 23.Evdokimov E, Sharma P, Lockett SJ, Lualdi M, Kuehn MR. Loss of SUMO1 in mice affects RanGAP1 localization and formation of PML nuclear bodies, but is not lethal as it can be compensated by SUMO2 or SUMO3. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:4106–4113. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alkuraya FS, Saadi I, Lund JJ, Turbe-Doan A, Morton CC, Maas RL. SUMO1 haploinsufficiency leads to cleft lip and palate. Science. 2006;313:1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1128406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song T, Li G, Jing G, Jiao X, Shi J, Zhang B, Wang L, Ye X, Cao F. SUMO1 polymorphisms are associated with non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:1265–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shao R, Zhang FP, Tian F, Anders Friberg P, Wang X, Sjoland H, Billig H. Increase of SUMO-1 expression in response to hypoxia: direct interaction with HIF-1alpha in adult mouse brain and heart in vivo. FEBS Lett. 2004;569:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guo D, Li M, Zhang Y, Yang P, Eckenrode S, Hopkins D, Zheng W, Purohit S, Podolsky RH, Muir A, et al. A functional variant of SUMO4, a new I kappa B alpha modifier, is associated with type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2004;36:837–841. doi: 10.1038/ng1391. This study along with Ref. [29] demonstrates the functional relationship between human SUMO4 SNP (SUMO4-M55V) and type1 diabetes.

- 28.Wang CY, She JX. SUMO4 and its role in type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24:93–102. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohren KM, Nadkarni V, Song JH, Gabbay KH, Owerbach D. A M55V polymorphism in a novel SUMO gene (SUMO-4) differentially activates heat shock transcription factors and is associated with susceptibility to type I diabetes mellitus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27233–27238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang CY, Yang P, Li M, Gong F. Characterization of a negative feedback network between SUMO4 expression and NFkappaB transcriptional activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381:477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desterro JM, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT. SUMO-1 modification of IkappaBalpha inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell. 1998;2:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fatkin D, MacRae C, Sasaki T, Wolff MR, Porcu M, Frenneaux M, Atherton J, Vidaillet HJ, Jr, Spudich S, De Girolami U, et al. Missense mutations in the rod domain of the lamin A/C gene as causes of dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction-system disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1715–1724. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jakobs PM, Hanson EL, Crispell KA, Toy W, Keegan H, Schilling K, Icenogle TB, Litt M, Hershberger RE. Novel lamin A/C mutations in two families with dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction system disease. J Card Fail. 2001;7:249–256. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2001.26339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capell BC, Collins FS. Human laminopathies: nuclei gone genetically awry. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:940–952. doi: 10.1038/nrg1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mattout A, Dechat T, Adam SA, Goldman RD, Gruenbaum Y. Nuclear lamins, diseases and aging. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nacerddine K, Lehembre F, Bhaumik M, Artus J, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Babinet C, Pandolfi PP, Dejean A. The SUMO pathway is essential for nuclear integrity and chromosome segregation in mice. Dev Cell. 2005;9:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.007. This paper demonstrates the phyriological role of sumoylation with Ubc9−/− mice which reveal embronic lethality because of abnormal nuclear integrity and widespread apoptosis.

- 37. Rytinki MM, Kaikkonen S, Pehkonen P, Jaaskelainen T, Palvimo JJ. PIAS proteins: pleiotropic interactors associated with SUMO. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3029–3041. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0061-z. A comprehensive review of the PIAS proteins and its binding partners.

- 38. Liu B, Liao J, Rao X, Kushner SA, Chung CD, Chang DD, Shuai K. Inhibition of Stat1-mediated gene activation by PIAS1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10626–10631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10626. The authors show that PIAS1 inhibits transcriptional activity of Stat1 through inhibition of DNA binding against promoter of Stat1-targeting gene.

- 39. Schmidt D, Muller S. Members of the PIAS family act as SUMO ligases for c-Jun and p53 and repress p53 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2872–2877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052559499. This paper is the first to identify PIAS proteins as SUMO E3 ligase characterized with SP-RING domain that are similar to RING domain of ubiquitin E3 ligases.

- 40. Liu B, Mink S, Wong KA, Stein N, Getman C, Dempsey PW, Wu H, Shuai K. PIAS1 selectively inhibits interferon-inducible genes and is important in innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:891–898. doi: 10.1038/ni1104. The authors generated systemic deletion mutant mice against pias1 that show normal development and are susceptible for viral and microviral infection.

- 41.Roth W, Sustmann C, Kieslinger M, Gilmozzi A, Irmer D, Kremmer E, Turck C, Grosschedl R. PIASy-deficient mice display modest defects in IFN and Wnt signaling. J Immunol. 2004;173:6189–6199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong KA, Kim R, Christofk H, Gao J, Lawson G, Wu H. Protein inhibitor of activated STAT Y (PIASy) and a splice variant lacking exon 6 enhance sumoylation but are not essential for embryogenesis and adult life. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5577–5586. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5577-5586.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tahk S, Liu B, Chernishof V, Wong KA, Wu H, Shuai K. Control of specificity and magnitude of NF-kappa B and STAT1-mediated gene activation through PIASy and PIAS1 cooperation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11643–11648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701877104. This study along with Ref. [42] suggest that PIASy deficiency can be compensated by PIAS1 but toll-like receptor signaling pathway is specifically regulated by PIASy.

- 44.Bischof O, Schwamborn K, Martin N, Werner A, Sustmann C, Grosschedl R, Dejean A. The E3 SUMO ligase PIASy is a regulator of cellular senescence and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2006;22:783–794. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moll UM, Wolff S, Speidel D, Deppert W. Transcription-independent pro-apoptotic functions of p53. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu B, Yang Y, Chernishof V, Loo RR, Jang H, Tahk S, Yang R, Mink S, Shultz D, Bellone CJ, et al. Proinflammatory stimuli induce IKKalpha-mediated phosphorylation of PIAS1 to restrict inflammation and immunity. Cell. 2007;129:903–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pascual G, Fong AL, Ogawa S, Gamliel A, Li AC, Perissi V, Rose DW, Willson TM, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK. A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-gamma. Nature. 2005;437:759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature03988. This study demonstrates how PPAR-gamma ligand depresses inflammatory response through PPAR-gamma-sumoylation. Ligand treatment increases sumoylation of PPAR-gamma and sumoylated PPAR-gamma binds to NF-κB and inhibits its transcriptional activity.

- 48.Stehmeier P, Muller S. Phospho-regulated SUMO interaction modules connect the SUMO system to CK2 signaling. Mol Cell. 2009;33:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hauck L, Harms C, An J, Rohne J, Gertz K, Dietz R, Endres M, von Harsdorf R. Protein kinase CK2 links extracellular growth factor signaling with the control of p27(Kip1) stability in the heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:315–324. doi: 10.1038/nm1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim YH, Sung KS, Lee SJ, Kim YO, Choi CY, Kim Y. Desumoylation of homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2) through the cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling of the SUMO-specific protease SENP1. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6272–6278. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li X, Luo Y, Yu L, Lin Y, Luo D, Zhang H, He Y, Kim YO, Kim Y, Tang S, et al. SENP1 mediates TNF-induced desumoylation and cytoplasmic translocation of HIPK1 to enhance ASK1-dependent apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:739–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamaguchi T, Sharma P, Athanasiou M, Kumar A, Yamada S, Kuehn MR. Mutation of SENP1/SuPr-2 reveals an essential role for desumoylation in mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5171–5182. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.5171-5182.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cheng J, Kang X, Zhang S, Yeh ET. SUMO-specific protease 1 is essential for stabilization of HIF1alpha during hypoxia. Cell. 2007;131:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.045. The authors show that SENP1 null mice are embryonic lethal and defect in erythropoiesis via sumoylation-dependent protein degradation of HIF1α and subsequent downregulation of erythropoietin expression.

- 54. Chiu SY, Asai N, Costantini F, Hsu W. SUMO-specific protease 2 is essential for modulating p53-Mdm2 in development of trophoblast stem cell niches and lineages. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060310. This study decribes the functional role of SENP2 with systemic SENP2−/− mice that show embryonic lethality and defect in G1-S transition through Mdm2-sumoylation and subsequent p53 stabilization.

- 55.Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420:25–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:508–519. doi: 10.1038/nri1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akaike M, Che W, Marmarosh NL, Ohta S, Osawa M, Ding B, Berk BC, Yan C, Abe J. The hinge-helix 1 region of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma1 (PPARgamma1) mediates interaction with extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 and PPARgamma1 transcriptional activation: involvement in flow-induced PPARgamma activation in endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8691–8704. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8691-8704.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kasler HG, Victoria J, Duramad O, Winoto A. ERK5 is a novel type of mitogen-activated protein kinase containing a transcriptional activation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8382–8389. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8382-8389.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayashi M, Kim SW, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Yoshida T, Abel ED, Eliceiri B, Yang Y, Ulevitch RJ, Lee JD. Targeted deletion of BMK1/ERK5 in adult mice perturbs vascular integrity and leads to endothelial failure. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1138–1148. doi: 10.1172/JCI19890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Surapisitchat J, Yoshizumi M, Hoefen R, Yan C, Berk BC. Fluid Shear Stress Inhibits TNF-a Activation of JNK, but not ERK1/2 or p38 in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Proc natl Acad Sci. 2001 doi: 10.1073/pnas.101134098. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collins AR, Meehan WP, Kintscher U, Jackson S, Wakino S, Noh G, Palinski W, Hsueh WA, Law RE. Troglitazone inhibits formation of early atherosclerotic lesions in diabetic and nondiabetic low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:365–371. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gong X, Tang X, Wiedmann M, Wang X, Peng J, Zheng D, Blair LA, Marshall J, Mao Z. Cdk5-mediated inhibition of the protective effects of transcription factor MEF2 in neurotoxicity-induced apoptosis. Neuron. 2003;38:33–46. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang J, Gocke CB, Yu H. Phosphorylation-facilitated sumoylation of MEF2C negatively regulates its transcriptional activity. BMC Biochem. 2006;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haffner SM. Coronary heart disease in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1040–1042. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, Chait A, Eckel RH, Howard BV, Mitch W, Smith SC, Jr, Sowers JR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999;100:1134–1146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ding B, Abe J, Wei H, Huang Q, Walsh RA, Molina CA, Zhao A, Sadoshima J, Blaxall BC, Berk BC, et al. Functional role of phosphodiesterase 3 in cardiomyocyte apoptosis: implication in heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:2469–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165128.39715.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ding B, Abe J, Wei H, Xu H, Che W, Aizawa T, Liu W, Molina CA, Sadoshima J, Blaxall BC, et al. A positive feedback loop of phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE3) and inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) leads to cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14771–14776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506489102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gregoire S, Yang XJ. Association with class IIa histone deacetylases upregulates the sumoylation of MEF2 transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2273–2287. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2273-2287.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]