Abstract

This study examined putative subtypes of pathological gamblers (PGs) based on the Pathways Model, and it also evaluated whether the subtypes would benefit differentially from treatment. Treatment-seeking PGs (N = 229) were categorized into Pathways subtypes based on scores from questionnaires assessing anxiety, depression and impulsivity. The Addiction Severity Index Gambling assessed severity of gambling problems at baseline, post-treatment and 12-month follow-up. Compared with Behaviorally Conditioned (BC) gamblers, Emotionally Vulnerable (EV) gamblers had higher psychiatric and gambling severity, and were more likely to have a parent with a psychiatric history. Antisocial Impulsive (AI) gamblers also had elevated gambling and psychiatric severity relative to BC gamblers. They were more likely to have antisocial personality disorder and had the highest legal and family/social severity scores. They were also most likely to have a history of substance abuse treatment, history of inpatient psychiatric treatment, and a parent with a substance use or gambling problem. AI and EV gamblers experienced greater gambling severity throughout treatment than BC gamblers, but all three subtypes demonstrated similar patterns of treatment response. Thus, the three Pathways subtypes differ based on some baseline characteristics, but subtyping did not predict treatment outcomes beyond a simple association with problem gambling severity.

Keywords: Pathological gambling, Pathways model, depression, impulsivity, gambling subtype

The etiology of pathological gambling (PG) is multifaceted. Numerous factors place one at risk for developing gambling problems (e.g., early wins, erroneous beliefs about gambling, impulsivity, emotional problems), and individuals may develop this disorder though more than one route. Blaszczynski and Nower (2002) proposed the Pathways Model as an etiological framework for understanding PG. According to this model, three different subtypes of pathological gamblers (PGs) exist: Behavioral Conditioned (BC), Emotionally Vulnerable (EV) and Antisocial-Impulsive (AI). Theoretically, each subtype develops PG via different factors. Because of the putative differences in etiology, prognosis and treatment recommendations may also differ.

BC gamblers purportedly develop PG via repeated exposure to gambling, and gambling problems are maintained through the behavioral contingencies associated with the games (Blasczcynski & Nower, 2002). Precipitants of PG in this subtype might include exposure to gambling, and studies have confirmed that proximity to gambling opportunities contributes to greater prevalence of PG (Gerstein et al., 1999). Factors related to the games themselves, such as near misses, may also promote continued gambling (Kassinove & Schare, 2001). The potential for winning, combined with increased autonomic arousal, appears to be an important factor in maintaining feelings of subjective excitement among gamblers (Wulfert, Roland, Hartley, Wang, & Franco, 2005). Further, PGs appear to perceive greater control over the outcomes of their gambling than do individuals without gambling problems (Moore & Ohtsuka, 1999). Taken together, availability of gambling, arousal/excitement, irrational cognitive schemas and habituation all appear to be precursors to problematic gambling behaviors, and these factors are purported to be causes of PG among BC gamblers.

However, these factors, according to the Pathways Model, are not unique to the BC subtype. What sets the BC gamblers apart is that they have the least severe gambling problems and are unlikely to experience substantial premorbid psychopathology. These gamblers may fluctuate between heavy recreational and pathological gambling. Because of their relatively good premorbid functioning, BC gamblers may be the most amenable to change, and they may experience the greatest success in treatment.

EV gamblers have similar precursors to their gambling problems. However, they differ from BC gamblers in that they use gambling as a way to modulate painful affect. These individuals ostensibly have poor emotional coping skills, and they purportedly experience depression and/or anxiety before their gambling problems, which they attempt to ameliorate by gambling. Biological vulnerabilities (e.g., serotonergic and noradrenergic processes) are proposed underlying mechanisms driving the relationship between mood and gambling among EV gamblers. With regard to treatment, the presence of a mood disorder appears to be associated with longer time to achieving stable abstinence (Hodgins, Peden, & Cassidy, 2005). Consequently, Blaszczynski and Nower (2002) suggest that, in comparison to BC gamblers, EV gamblers may be more resistant to behavior change, and treatment interventions that address both problematic gambling and underlying mood vulnerabilities may be needed for a successful gambling reduction in this subtype.

Finally, Blaszczynski and Nower (2002) consider the AI gamblers to be the most disturbed subtype. Similar to the EV gamblers, these individuals tend to have significant emotional vulnerability, and they experience elevated psychopathology. However, the emotional vulnerabilities among AI gamblers may also involve more emotional dysregulation, as seen in disorders such as borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder, whereas EV gamblers may be primarily prone to negative affect (e.g., depression and anxiety disorders). Unlike the other subtypes, AI gamblers are characterized by high levels of trait impulsivity and neurological dysfunction, which, in combination with elevated psychopathology, are considered unique etiological factors that lead to their gambling problems. They are ostensibly more likely to engage in criminal acts, have drug or alcohol problems, and exhibit antisocial traits. Thus, processes involving arousal and excitement, while relevant to all subtypes, may have particular salience for AI gamblers. Blaszczynski and Nower (2002) recommend that treatment for AI gamblers must address not only the gambling, but also a wide range of other dysfunctions (e.g., antisocial personality traits, attention problems, treatment compliance issues) that accompany PG, and they recommend intensive therapy to address impulse control issues. Treatment outcomes for substance dependent individuals with antisocial traits are often poorer than for those without such traits (e.g., Compton, Cottler, Jacobs, Ben-Abdallah & Spitznagel, 2003; Woody, McLellan, Luborsky, & O’Brien, 1985), suggesting that AI gamblers may also not respond well to treatment for their gambling problems.

Substantive data from epidemiological and treatment studies support the contention that PGs as whole have emotional vulnerabilities and large proportions suffer from antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and impulsive traits. Epidemiological research indicates that over 50% of PGs have a lifetime mood disorder, over 40% have a lifetime anxiety disorder, and about 23% have ASPD (Kessler et al. 2008; Petry, Stinson & Grant, 2005). Similarly, high proportions of treatment seeking PGs suffer from mood and anxiety disorders (Crockford & el-Guebaly, 1998; Hodgins et al., 2005), and up to 17% have ASPD (Pietrzak & Petry, 2005). In comparison, up to 17% of adults in the general population have experienced a lifetime major depressive episode, about 17% have suffered from anxiety disorders in the past 12-months, and about 2–3% have lifetime ASPD (Kessler, et al., 1994; Moran, 1999; Weissman et al., 1996). Further, studies reveal that PGs are generally more impulsive than non-PGs (Ledgerwood, Alessi, Phoenix, & Petry, 2009; Petry, 2001; Steel & Blaszczynski, 1998; Vitaro, Arseneault, & Tremblay, 1999).

Although PGs suffer from emotional dysregulation and impulsive tendencies consistent with Pathways subtypes, few studies have directly assessed the Pathways Model. We previously identified some characteristics related to the EV and AI subtypes in PGs from 7 different treatment sites (Ledgerwood & Petry, 2006). Gambling to escape from emotional problems was associated with dissociation experiences and with female gender. Gambling-related egotism, a factor conceptually associated with the AI subtype, was significantly related to male gender and impulsivity. However, this study did not systematically examine the validity of the Pathways Model as a useful assessment heuristic, or as a predictor of treatment outcome.

In a study of PGs who drink while gambling, Stewart, Zack, Collins, Klein, & Fragopoulos (2008) used cluster analysis to identify three potential subtypes of PG based on responses to a measure of gambling situations. These subtypes included Enhancement Gamblers who use gambling for positive reinforcement, Coping Gamblers who use gambling for negative reinforcement (i.e., to reduce an aversive state) and Low Emotion Regulation Gamblers who generally do not use gambling as a way to modulate affect. Although these three subtypes have some similarities to Blaszczynski & Nower’s (2002) model, this study was not an investigation of the Pathways Model per se and was limited to non-treatment seeking gamblers who drink. Somewhat inconsistent with the Pathways model, these authors found Coping Gambler (similar to EV gamblers) to be relatively high on impulsivity and Enhancement Gamblers (most similar to AI) to be lower in anxiety and depression.

In another study, Stewart and Zack (2008) conducted a factor analysis of gambling motives of community-recruited PGs. Factors extracted included social (i.e., gambling for recreational purposes), coping (i.e., gambling to decrease negative affect), and enhancement (i.e., gambling to enhance positive affect) factors. Coping and enhancement factors appeared to predict gambling frequency and loss of control over gambling. Turner, Turner, Jain, Spence, and Zangeheh (2008) studied responses from community-recruited PGs on measures of impulsivity, depression, anxiety, erroneous beliefs, and early gambling wins. Four factors identified in factor analysis included emotional vulnerability, impulsivity, erroneous beliefs, and experiences of wins. Emotional vulnerability and impulsivity corresponded with Blaszczynski and Nower’s (2002) proposed EV and AI subtypes, respectively. Erroneous beliefs about gambling and experience of wins corresponded with the BC subtype.

Lesieur (2001) described potential PG subtypes determined through cluster analysis of the responses of inpatient PGs to questionnaires examining gambling severity, impulsivity, excitement seeking, depression, anxiety, escape, dissociation and other factors. He identified three subtypes: (1) “Normal” PGs who had relatively few difficulties beyond gambling; (2) Moderately Impulsive Action Seekers who had intermediate levels of psychopathology and implusiveness, younger age of gambling onset, higher excitement seeking and endorsement of narcissism and power themes related to gambling; and (3) Impulsive Escape Seekers who were more severely impulsive (relative to the other subtypes), more likely to score high on anxiety and depression measures, and more likely to experience dissociation and to use gambling to escape from painful affect. Although some similarities with Blaszczynski and Nower’s (2002) typologies exist, Lesieur’s (2001) study did not identify a purely EV subtype with lower impulsivity. Perhaps because data were derived from an inpatient sample, they may have had particularly severe or refractory PG symptoms. Further, none of the above studies addressed treatment outcomes based on subtypes.

In summary, only a handful of studies have examined subtypes of PGs. No study to our knowledge has examined how these putative subtypes of PGs respond to treatment interventions.

In this study, we used responses from impulsivity, depression and anxiety assessments administered to PGs initiating a randomized clinical trial of psychosocial treatment for PG to categorize participants into subtypes based on the Pathways Model. We hypothesized that: 1) participants scoring low on both anxiety and depression (the most commonly reported types of psychopathology among PGs) would experience less severe gambling problems and fewer family/social and lifetime psychiatric problems than gamblers who scored high on these measures, consistent with the BC subtype; 2) participants high in anxiety and/or depression, but lower on impulsivity (consistent with the EV subtype), would experience significantly greater overall psychopathology, history of family psychopathology and emotional coping difficulties than BC gamblers, but fewer legal problems and antisocial personality disorder symptoms than those with high impulsivity; 3) participants high in both impulsivity and anxiety/depression (consistent with the AI subtype) would experience greater legal problems, higher rates of antisocial personality disorder, greater personal and familial history of addiction and psychopathology, and have started gambling at an earlier age than gamblers in the other subtypes.

Consistent with the Pathways Model (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002), we also predicted that those in the BC subtype would have the best overall treatment response. We hypothesized that EV gamblers would respond well to individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) because of its emphasis on altering cognitions and adverse moods associated with gambling (Petry, 2005), but that overall they may experience slower recovery than those in the BC subtype. Finally, we anticipated that AI subtype may be relatively refractory to the brief treatments provided.

Methods

Participants

PGs from the community were recruited via advertisements to participate in a study examining the efficacy of psychotherapy for PG. Inclusion criteria were a current diagnosis of PG, presence of gambling in the preceding 2 months, age 18 or older, and able to read at a 5th grade level. Exclusion criteria were acute or uncontrolled psychiatric symptoms (e.g., current suicidal intent or acute psychosis) and current enrollment in treatment for PG. Individuals with depression and anxiety symptoms were not excluded unless these symptoms were accompanied by acute uncontrolled psychosis or suicidality. Participants who appeared to meet inclusion criteria based on a telephone interview were scheduled for an in-person interview, at which time full inclusion and exclusion criteria were evaluated. In total, 231 participants were included in the treatment study. Complete data on 229 were available for comparisons between subtypes of gamblers on demographic, gambling, legal, psychosocial and drug use variables. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine approved the study, and participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation.

Measures

Measures were administered at baseline, post-treatment (month 2) and at follow-up evaluations scheduled for months 6 and 12. Participants were paid $15 for completing the 2 and 6 month interviews, and $20 for completing the 12-month interview.

Demographic items included age, gender, marital status, racial and ethnic identification, number of years of education, current employment status and yearly income.

South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS)

The SOGS is a 20-item measure of PG based on DSM-III diagnostic criteria, with good convergent validity and reliability (Lesieur & Blume, 1987; Stinchfield, 2002; Strong, Leiseur, Breen, Stinchfield & Lejuez, 2004) and can assess both recent and lifetime gambling problems. Scores of 5 or more are generally considered indicative of meeting diagnostic criteria for PG when the SOGS is used to assess treatment-seeking problem gamblers (Stinchfield, 2002).

Time Line Follow-Back for gambling (G-TLFB)

The G-TLFB evaluated the frequency and intensity of gambling. It is a calendar-based measure based on the TLFB for substance use (Sobell & Sobell, 1992). The G-TLFB has good validity and reliability in assessing gambling (Hodgins & Makarchuk, 2003; Weinstock, Whelan, & Meyers, 2004).

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)

Current depression and anxiety symptoms were assessed using the corresponding scales from the BSI (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983; Derogates, 1993). The depression and anxiety scales of the BSI have good validity and reliability (Derogatis, 1993), and were used to distinguish between participants with high and low anxiety and/or depression. Derogatis and Melisaratos (1983) reported that the depression and anxiety scales exhibited good convergent validity when compared with similar MMPI scales. As described in the data analysis section, we used gender-based normative data from a non-clinical sample (Derogatis, 1993) to establish our depression/anxiety vs. non-depression/anxiety group cutoff scores.

Eysenck Impulsivity Scale - 7 (EIS-7)

The Impulsiveness subscale of the EIS-7 was used to measure impulsivity (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1978; Eysenck & McGurk, 1980). As outlined in the data analysis section, participants were dichotomized into low and high impulsivity groups using gender-based norms developed for non-clinical adults (Eysenck, Pearson, Easting, & Allsopp, 1985).

Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

The ASI is a structured interview that assesses psychosocial consequences of addiction. It has seven domains, including medical, employment, alcohol, drug, legal, family/social and psychiatric (McLellan et al., 1985). The ASI has demonstrated reliability and validity (Kosten, Rounsaville & Kleber, 1983; McLellan et al., 1985), including in PGs (Petry, 2007). We also included a valid and reliable gambling severity index (Lesieur & Blume, 1992; Petry, 2003). In addition to composite scores, we also used ASI items that evaluated personal and parental problems with gambling, substances and psychiatric treatment.

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) was assessed using a modified version of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Conduct Disorder (CD) and ASPD section (First et al., 1997). Participants were coded as having ASPD if they endorsed at least 3 CD symptoms prior to age 18 and at least 3 symptoms of ASPD since age 18.

The Coping Strategies Scale (CSS; Litt, Kadden, Cooney, & Kabela, 2003; Prochaska, Velicer, DiClemente, & Fava, 1988) was modified from scales assessing change processes for altering smoking and alcohol behaviors to specifically address gambling (Petry, Litt, Kadden, & Ledgerwood, 2007). The CSS consists of 58 items rated on a scale of 1 (‘never’) to 4 (‘frequently’), and are combined to create an overall coping composite score. In the present study, we focused on emotional coping, using the Emotional Subscale, which has evidenced good psychometric qualities (Litt et al., 2003; Petry et al., 2007). We found the Emotional Scale of the CSS to have good internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91).

Procedure

Participants were enrolled in a treatment study described by Petry and colleagues (2006). After a baseline interview, participants were randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions: 1) Gamblers Anonymous (GA) referral; 2) GA referral plus a CBT workbook; or 3) GA referral plus 8 sessions of individual CBT. All participants were encouraged to select a GA meeting to attend from a list of local GA meetings. Additionally, workbook group participants were given a 70-page workbook that included several CBT-oriented exercises and a section on handling gambling-related debt, and they were advised to complete an exercise per week for eight weeks. Individual CBT participants met with a study therapist for eight weekly 50-minute individual CBT sessions. Individual CBT sessions and workbook chapters covered identical topics and included: 1) Discovering triggers (including mood triggers); 2) Functional analysis; 3) Pleasant activities; 4) Self-management planning; 5) Coping with craving and urges; 6) Assertiveness and gambling refusal skills; 7) Irrational thinking; and 8) Coping with lapses. The content of the sessions is more fully described elsewhere (Morasco, Weinstock, Ledgerwood, & Petry, 2007; Petry, 2005). Participants were not randomized based on their Pathway subtype assignment and had an equal chance of being in each of the three treatment conditions.

Analysis

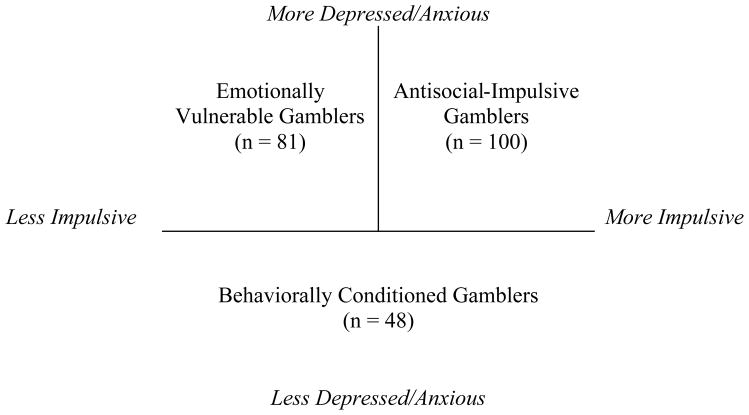

Baseline scores on the EIS-7 and the Depression and Anxiety scales of the BSI were used to classify participants into one of the three pathway subtypes. Participants were classified as high on depression and/or anxiety if either scale score was more than one standard deviation higher than the gender-based norms provided by Derogatis (Derogatis, 1993; Depression scale M = 0.06, SD = 0.44 for men, and M = 0.18, SD = 0.48 for women; Anxiety scale M = 0.18, SD = 0.36 for men, and M = 0.30, SD = 0.53 for women). Participants who scored lower than one standard deviation above the mean on depression/anxiety (and thus were average or below average with respect to these psychological symptoms) were assigned to the BC subtype. Participants were characterized as high on impulsivity if their EIS-7 score was one standard deviation or more above the average normative sample score as assessed by Eysenck et al. (1985; M = 6.55, SD = 4.43 for men and M = 7.48, SD = 4.42 for women). Participants who scored less than one standard deviation above the normative mean were placed in the low to average impulsivity group. Among those participants who scored high on the depression/anxiety measures, those who scored relatively lower on the impulsivity measure were assigned to the EV subtype, and those who scored high on impulsivity were assigned to the AI subtype. Numbers of individuals in each subtype are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Group assignment based on high and low impulsivity and depression/anxiety scores, and consistent with the Pathways Model of PG.

Subtype differences on baseline demographic and gambling variables were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), Kruskal-Wallis or chi square techniques as appropriate. Tukey’s post-hoc analyses were conducted to determine specific subtype differences for ANOVAs. Variables that were not normally distributed were transformed using square root or log transformation techniques whenever possible. Non-parametric Kruskal Wallis tests analyzed differences in ASI scale scores. When significant effects were identified, Mann-Whitney U tests identified specific differences between any two Pathway subtypes.

Two sets of analyses were conducted to determine whether Pathways subtypes responded differentially to treatment. We included only individuals who participated in the baseline, post-treatment [2 month], and either 12- or 6-month follow up time-points. Complete follow-up data were available for 171 participants (over 74% of the original randomized sample). For most participants (n = 158), 12-month follow-up data were used as the final follow-up in the analyses. The other 13 participants included did not provide 12-month follow-up data, and we substituted data from the 6-month assessment. The remaining 61 participants either did not complete the 6- and 12-month follow-up assessment, or were missing data on one or more measure, preventing their inclusion. EV gamblers (14.8%) were significantly less likely to be lost to follow-up than either BC gamblers (31.3%) or AI gamblers (32.0%; χ2(2)=7.87, p < .05).

Two chi-square analyses were conducted to examine whether Pathways groups differentially responded to treatment. One analysis examined differences in the number of PGs in each Pathways subtype who no longer scored 5 or higher on the SOGS (score < 5) at the final follow-up. The other analysis examined the number of PGs in each Pathways subtype who were no longer symptomatic, according to the SOGS at follow-up (score = 0).

Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to test for Pathway subtype differences in changes in gambling severity. Consistent with the primary outcomes paper (Petry et al., 2006), ASI-G composite scores (which take into account days and dollars wagered in the past month) from baseline, post-treatment and the final follow-up were the dependent variables. The independent variable was subtype: BC, EV and AI. Treatment condition was also included to account for differential reductions in gambling severity that were due to treatment randomization.

Results

The three subtypes categorized by impulsivity and depression/anxiety scores are illustrated in Figure 1. The number of participants in each subtype is presented in Table 1 along with subtype differences on demographic, gambling and psychiatric variables. Participants in each Pathway subtype were equally likely to be randomly assigned to the three treatment conditions. Age, race, employment status and marital status were similar across subtypes. Women were over represented among the gamblers in the EV subtype relative to the other two subtypes (p < .01). Significant differences were also found for level of education completed, with AI participants having the lowest education levels overall (p < .05).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of gambling subgroups.

| Variable | Behaviorally Conditioned N = 48 | Emotionally Vulnerable N = 81 | Antisocial Impulsive N = 100 | F or χ2 and p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female N(%) | 18(37.5) | 48(59.3) | 37(37.0) | χ2(2)=10.33, p<.01 |

| Age M(SD) | 45.9(11.8) | 46.2(10.0) | 43.1(11.0) | F(2,226)=2.19, p = .11 |

| Race N(%) | χ2(8)=6.01, p = .64 | |||

| Caucasian | 40(83.3) | 69(85.2) | 84(84.0) | |

| African American | 7(14.6) | 5(16.2) | 8(8.0) | |

| Hispanic | 0(0) | 5(6.2) | 5(5.0) | |

| Asian | 0(0) | 1(1.2) | 1(1.0) | |

| Other | 1(2.1) | 1(1.2) | 2(2.0) | |

| Employed Full or Part Time (N%) | 34(70.8) | 61(75.3) | 69(69.0) | χ2(2)=0.89, p = .64 |

| Education | χ2(4)=10.21, p < .05 | |||

| < High school | 0(0) | 5(6.2) | 13(13.0) | |

| High School | 14(29.2) | 20(24.7) | 32(32.0) | |

| College | 34(70.8) | 56(69.1) | 55(55.0) | |

| Marital N(%) | χ2(6)=3.79, p=.71 | |||

| Never Married | 17(35.4) | 20(24.7) | 29(29.0) | |

| Married | 21(43.8) | 35(43.2) | 38(38.0) | |

| Separated/Divorced | 9(18.8) | 21(25.9) | 28(28.0) | |

| Widow | 1(2.1) | 5 (6.2) | 5(5.0) | |

| Treatment Group Assignment | χ2(4)=0.91, p = .92. | |||

| GA Only | 14(29.2) | 20(24.7) | 28(28.0) | |

| Manual + GA | 15(31.3) | 31(38.3) | 30(37.0) | |

| Therapy + GA | 19(39.6) | 30(37.0) | 35(35.0) | |

| ASPD N(%) | 4(8.3) | 5(6.2) | 26(26.0) | χ2(2)=15.85, p<0.001 |

| Gambling Related Illegal Behavior N(%) | 10(20.8) | 19(23.5) | 34(34.0) | χ2(2)=3.85, p = .15 |

| Drug or Alcohol Treatment N(%) | 10(20.8) | 16(19.8) | 35(35.0) | χ2(2)=6.37, p < .05 |

| Inpatient Psychiatric Treatment N(%) | 7(14.6) | 12(14.8) | 28(28.0) | χ2(2)=6.08, p < .05 |

| Parent(s) With Substance Abuse or Gambling Problems N(%) | 24(50.0) | 46(56.8) | 70(70.0) | χ2(2)=6.46, p < .05 |

| Parent(s) With Significant Psychiatric Problem N(%) | 10(20.8) | 34(42.0) | 42(42.0) | χ2(2)=7.24, p < .05 |

| CSS Emotional Coping Score** | 2.8(0.7)a | 2.7(0.5) | 2.6(0.6)b | F(2,222)=3.05, p < .05 |

| Age First Gambled * M(SD) | 19.0(10.2) | 22.0(10.7) | 19.7(11.3) | F(2,226)=1.77, p = .17 |

| SOGS – Lifetime M(SD) | 11.1(3.6)a | 12.1(3.1)a | 13.6(3.4)b | F(2,226)=9.96, p<.001 |

| SOGS – 30 Days * M(SD) | 6.3(3.7)a | 9.0(3.3)b | 9.3(3.8)b | F(2,224)=11.66, p<.001 |

| ASI Gambling M(SD) | 0.56(0.26)a | 0.73(0.17)b | 0.76(0.18)b | F(2,226)=17.07,p<.001 |

| Days Gambled Last Month * M(SD) | 10.6(9.7) | 11.5(9.7) | 13.1(10.2) | F(2,226)=1.53, p = .22 |

| Dollars Gambled\Last Month ** Median(IQ) | $2400(4650) | $2000(4075) | $2000(3978) | F(2,226)=1.42, p = .24 |

ASPD = antisocial personality disorder; SOGS = South Oaks Gambling Screen; ASI = Addiction Severity Index; N = number of cases; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; IQ = interquartile range.

Square root transformed prior to analysis;

Log transformed prior to analysis (Untransformed means and standard deviations are presented for variables transformed for analysis).

Groups with different superscripts differ significantly from one another as follows: a < b (p < .05).

As hypothesized, AI gamblers were more likely than the other two subtypes to meet diagnostic criteria for ASPD (p < .001; Table 1). As predicted, they also were most likely to have a history of drug or alcohol treatment, and a history of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (p < .05). Compared to the other subtypes, AI gamblers were significantly more likely to have a parent with a history of addiction (i.e., alcohol, drug or gambling problem; p < .05), and both EV and AI gamblers were more likely than BC gamblers to have a parent with a history of psychiatric problems (p < .05). A significant main effect of subtype was found for emotional coping styles (p < .05), and post hoc analysis revealed that the AI subtype reported significantly poorer emotional coping than the BC subtype. Contrary to our hypothesis, subtypes did not differ on rates of gambling-related illegal behaviors in the year prior to seeking treatment.

As predicted, BC gamblers had the lowest scores on the lifetime and past-month SOGS and on the ASI-G (p’s < .05). EV gamblers had lower lifetime SOGS scores than those in the AI subtype. Subtypes did not differ significantly on age of first gambling episode, number of days of gambling in the past month, or dollars gambled in the past month (all p’s > .05).

As shown in Table 2, significant pathway subtype differences were found for three ASI scales at baseline: Legal, Family/Social and Psychiatric. Pairwise comparisons of Legal composite scores (which assesses legal problem severity) revealed that the AI participants scored significantly higher than the EV participants (p < .05). Although over half the participants in each subtype scored 0 on the Legal scale, the means and standard deviations were M = 0.05 SD = 0.15, M = 0.04 SD = 0.14, and M = 0.09 SD = 0.18 for the BC, EV and AI subtypes, respectively. The AI subtype also scored significantly higher on the Family/Social composite score (which assesses severity of current problems, such as family conflict) than the BC participants (p < .05). Finally, as we hypothezied, both the EV and AI gamblers scored significantly higher than the BC gamblers on the Psychiatric composite score (which assesses overall severity of current psychiatric symptoms), and the AI subtype scored higher on this scale than the EV participants (p < .05).

Table 2.

Median Addiction Severity Index composite scores for each subgroup of gambler.

| Composite | Behaviorally Conditioned N = 48 | Emotionally Vulnerable N = 81 | Antisocial- Impulsive N = 100 | Kruskal Wallis Chi- Square (df=2) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | 0.22(0.48) | 0.33(0.56) | 0.19(0.67) | 1.92 | .38 |

| Employment | 0.11(0.45) | 0.14(0.40) | 0.14(0.42) | 1.48 | .48 |

| Alcohol | 0.03(0.14) | 0.00(0.06) | 0.02(0.14) | 5.02 | .08 |

| Drug | 0.00(0.00) | 0.00(0.00) | 0.00(0.00) | 0.90 | .64 |

| Legal | 0.00(0.00) | 0.00(0.00)a | 0.00(0.04)b | 9.31 | < .01 |

| Family/Social | 0.16(0.28)a | 0.20(0.32) | 0.28(0.39)b | 7.68 | < .05 |

| Psychiatric | 0.10(0.23)a | 0.34(0.27)b,c | 0.38(0.26)b,d | 56.80 | <.001 |

Note. Medians and interquartile ranges are presented. Groups with different superscripts differ significantly from one another as follows: a < b (p < .05); c < d (p < .05)

At the final follow-up, BC participants were more likely to be asymptomatic (i.e., completely free of symptoms on the SOGS; 38.2%) than were EV (17.4%) and AI (20.6%) gamblers (χ2 (2,171) = 5.94, p = .051). BC gamblers were also more likely to no longer score higher than 5 on the SOGS at final follow up (76.5%) compared with EV (40.6%) and AI (38.2%) gamblers (χ2 (2,171) = 15.10, p = .001). These data are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percent of gamblers in the Behaviorally Conditioned (BC), Emotionally Vulnerable (EV) and Antisocial Impulsive (AI) subtypes who were asymptomatic for gambling problems as defined by South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) scores of 0 and who were no longer gambling pathologically as defined by SOGS scores of <5 at the final follow up.

ASI-G scores declined significantly over time (F(2,322) = 135.82, p < .001; see Figure 3). A significant interaction occurred between time and study treatment condition (F(4,322) = 2.39, p < .05; data not shown). Patients randomly assigned to the individual therapy CBT condition showed more precipitous reductions in gambling over time than the other treatment conditions as noted in the main outcome paper (see Petry et al., 2006).

Figure 3.

Mean Addiction Severity Index – Gambling (ASI-G) scores at baseline, post-treatment and follow-up for Behaviorally Conditioned, Emotionally Vulnerable, and Antisocial-Impulsive participants.

Between subjects comparisons revealed significant differences among pathways subtypes (F(2,161) = 17.1, p < .001) with participants in the EV and AI subtypes having higher ASI-G scores at all time points relative to those in the BC subtypes. However, contrary to our initial predictions, the time X pathway subtype interaction (F(4,322) = .63, p = .64), the pathway subtype X treatment condition interaction (F(4,161) = 0.51, p = .59) and the time X pathway subtype X treatment condition interaction (F(8,322) = 1.19, p = .30) were not significant.

We initially grouped those with higher impulsivity but lower anxiety/depression into the BC group. We could have also made a case for including these individuals in the AI group. However, because of the relative lack of psychopathology among these individuals, we included them in the BC group. We repeated all of the analyses with the high impulsivity, low anxiety/depression individuals included in the AI group. The results were primarily the same with six exceptions: 1) ASI Legal composite was now significantly higher in the AI than EV gamblers; 2) AI and EV gamblers were no longer different from each other on the ASI Psychiatric factor; 3) significant omnibus differences were found for age, but no significant post-hoc analyses were evident between Pathways; 4) education now no longer differed based on Pathway subtype; 5) omnibus test differences for emotional coping were now only marginally significant; and 6) EV gamblers now scored slightly higher than AI gamblers on the Lifetime SOGS score (data not shown). Treatment analysis results did not change.

Discussion

This study provides evidence for the Pathways Model for subtyping PGs. As predicted, we found some evidence for the three pathways of Blaszczynski and Nower’s (2002) etiological model. First, there does appear to be a subtype of PGs with relatively less severe co-occurring psychosocial difficulties. Consistent with Lesieur’s (2001) “normal” gambler and Blaszczynski and Nower’s (2002) conceptualization of a BC gambler, these individuals experienced less severe gambling problems, had relatively lower levels of psychopathology and fewer family/social problems, and they were less likely to have a parent with a psychiatric history compared with the AI and EV gamblers. These individuals also had lower rates of ASPD, were less likely to have sought drug/alcohol treatment and were less likely to have a family history of addiction than AI gamblers. BC gamblers were the smallest group in the current study. Because these individuals experienced the fewest psychiatric problems and had the least severe gambling problems, it is possible that BC gamblers are underrepresented in this study of treatment seekers. Investigations of community PGs may recruit more BC gamblers.

EV gamblers had significantly higher psychiatric severity than the BC gamblers, but they also had fewer legal problems, were less likely to have ASPD, and had fewer addiction-related problems than the AI gamblers. Women had greater representation among the EV subtype, consistent with studies that find affective disorders and escape gambling more prominent among female than male PGs (e.g., Ibanez, Blanco, Moreryra, & Saiz-Ruiz, 2003; Ledgerwood & Petry, 2006; Stewart & Zack, 2008). These finding offer some confirmation of a subtype of PGs who do not experience significant impulsiveness and antisocial traits, but who do present with mood and anxiety problems.

Despite these consistencies with the Pathways Model, not all of our results confirmed our hypotheses with regard to EV gamblers. We found, for example, that while emotional coping differed between subtypes, EV gamblers did not experience significantly poorer emotional coping skills than BC gamblers. This finding is contrary to the literature that suggests depression among PGs may be associated with poorer coping (Getty, Watson, & Frisch, 2000), and the initial hypothesis of the Pathways Model that these individuals have poorer coping skills (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002). It may be that a larger sample size would reveal group differences.

As predicted, the AI subtype had high rates of ASPD and the most severe psychosocial problems. The AI gamblers acknowledged significantly greater current legal problem severity on the ASI, but even most AI gamblers denied current legal problems. These participants also reported the most severe family/social and psychiatric problems of all subtypes, and they had the lowest educational attainment. Contrary to the hypothesis, AI gamblers did not begin gambling at a significantly younger age than the other subtypes. Consistent with the model, AI gamblers did experience more addiction related issues, including having a parent with a history of addiction (i.e., alcohol, drug or gambling problem) and having personally sought treatment for a drug or alcohol problem.

With regard to treatment outcome data, BC gamblers were more likely to be asymptomatic and to no longer meet PG criteria at the final follow up point, indicating that these individuals are more likely to be in recovery when they complete treatment. However, our data support the conclusion that all three typologies improve at a similar rate. Because of their initially greater problem gambling severity, AI and EV participants still exhibited elevated problem gambling severity at the end of treatment and during the follow-up period relative to the BC gamblers. Other studies have found that impulsivity is associated with poor treatment response (Maccallum, Blaszczynski, Ladouceur, & Nower, 2007; Leblond, Ladouceur, & Blaszczynski, 2003), and the Pathways Model does not predict that AI gamblers would show the same marked improvements over time as other subtypes of gamblers. We also predicted that PGs who were classified in the EV subtype would respond particularly well to treatment if they received individual CBT. We found a significant main effect for treatment condition revealing that participants generally showed greater improvement in individual CBT, but no significant pathways subtype X treatment condition interaction was evident. Based on these findings, it appears that subtyping PGs based on the Pathways Model may not be a useful tool for making recommendations for the specific type of treatment, at least not with respect to CBT and GA referral treatments. Although, these two treatments were not specifically developed to address special needs of patients in the different pathways, it should be noted that GA and CBT approaches are among the most studied and most practiced treatments currently available. Thus, it is important to know how different groups of PGs may respond to these very different treatment approached.

Similarly, Project Match (Project Match Treatment Group, 1997) demonstrated little benefit of attempting to match patients to specific treatments based on initial clinical presentation. Such findings, however, are not universal, as a small number of studies have found some modest merit to matching based on personal characteristics (e.g., Conrod et al., 2000), and a re-examination of some of the Project Match data suggests that more complex models of matching may ultimately be needed to understand the intricacies of individual factors and treatment assignment (Witkiewitz, van der Maas, Hufford, & Marlatt, 2007).

One important limitation of this study is that we used current depression and anxiety symptoms to categorize PGs into a Pathways subtype. Thus, we did not assess the chronology of development of the PG and other psychopathology, nor did we assess psychiatric diagnoses. It is important that future studies assess order of onset of psychiatric illnesses to further determine the etiology of PG in different subtypes of gamblers. We also only evaluated CBT and GA referral treatments, and it is possible that different gambling subtype by treatment effects may have emerged if other types of interventions were compared. Another limitation is that we used only treatment-seeking PGs for the current investigation. It is possible that our participants differed in important ways from the general population of PGs in the community. Future studies should explore the Pathways Model in PGs from community or epidemiological settings, especially as relates to development and possible prevention of PG. Finally, several univariate tests were used, which increases family-wise error rate. Given the complexities of the research question, the types of data collected (continous and dichotomous), and the number of variables analyzed, there was no straightforward way to examine the data using techniques that would reduce or correct for this error rate. It is notable, however, that several of the predictions made about the direction and statistical significance of variables were confirmed by our analyses, suggesting that our conclusions with regard to the pathways are sound.

This study also had some important strengths. Participants reported gambling disorder severity ranging from mild to severe PG. It is also notable that nearly half of the participants in this study were women, as women have traditionally been under-represented in problem gambling research. Additionally, we had a large sample size, used random assignment to the three treatment conditions, and included a one-year follow-up with sufficient follow-up rates.

Overall, our study provides an initial empirical evaluation of the Pathways Model. Most of our hypotheses with regard to subtype assignment were confirmed by our analyses of baseline data, suggesting that the Pathways Model may be a valid way of categorizing PGs. Our initial hypotheses concerning the use of the Pathways Model to predict treatment outcome were largely disconfirmed. Although we demonstrated that PGs who were grouped into the more severe gambling subtypes (EV and AI) experience significantly elevated problem gambling severity throughout treatment and follow-up, they did not experience a different pattern of recovery from the BC gamblers. Evaluation of gambling severity may be the most important predictor of outcomes in response to the treatments evaluated in this study, but further examination of PG subtypes may be useful for understanding etiology and progression of the disorder.

Acknowledgments

This study and preparation of this report were supported in part by NIH grants R01-MH60417, R01-DA021567, P30-DA023918, and by Joseph Young Sr. funding from the State of Michigan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/adb

References

- Blaszczynski A, Nower L. A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction. 2002;97:487–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Cottler LB, Jacobs JL, Ben-Abdallah A, Spitznagel EL. The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:890–895. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Cote S, Fontaine V, Dongier M. Efficacy of brief coping skills interventions that match different personality profiles of female substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:231–242. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockford DN, el-Guebaly N. Psychiatric comorbidity in pathological gambling: A critical review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;43:43–50. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ. Impulsiveness and venturesomeness: Their position in a dimensional system of personality description. Psychological Reports. 1978;43:1247–1255. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1978.43.3f.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, McGurk BJ. Impulsiveness and venturesomeness in a detention center population. Psychological Reports. 1980;47:1299–1306. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1980.47.3f.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Pearson PR, Easting G, Allsopp JF. Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy in adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein D, Murphy S, Toce M, Hoffmann J, Palmer A, Johnson R, et al. Gambling impact and behavior study. Chicago: University of Chicago; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Getty HA, Watson J, Frisch GR. A comparison of depression and styles of coping in male and female GA members and controls. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2000;16:377–391. doi: 10.1023/a:1009480106531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, Makarchuk K. Trusting problem gamblers: Reliability and validity of self-reported gambling behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:244–248. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, Peden N, Cassidy E. The association between comorbidity and outcome in pathological gambling: A prospective follow-up of recent quitters. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2005;21:255–271. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-3099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez A, Blanco C, Moreryra P, Saiz-Ruiz J. Gender differences in pathological gambling. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:295–301. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassinove JI, Schare ML. Effects of the “near miss” and the “big win” on persistence at slot machine gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:155–158. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Hwang I, LaBrie R, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Winters KC, Shaffer HJ. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. Concurrent validity of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1983;171:606–610. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond J, Ladouceur R, Blaszczynski A. Which pathological gamblers will complete treatment. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;42:205–209. doi: 10.1348/014466503321903607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Alessi S, Phoenix N, Petry NM. Behavioral assessment of impulsivity in pathological gamblers with and without substance use disorder histories versus healthy controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Petry NM. Psychological experience of gambling and subtypes of pathological gamblers. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR. Cluster analysis of types of inpatient pathological gamblers. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2001;62(4-B):2065. (UMI No. 3011834) [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. Modifying the Addiction Severity Index for use with pathological gamblers. American Journal on Addictions. 1992;1:240–247. [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Cooney NL, Kabela E. Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive–behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:118–28. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccallum F, Blaszczynski A, Ladouceur R, Nower L. Functional and dysfunctional impulsivity in pathological gambling. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007:1829–1838. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O’Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran P. The epidemiology of antisocial personality disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1999;34:231–242. doi: 10.1007/s001270050138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasco BJ, Weinstock J, Ledgerwood DM, Petry NM. Psychological factors that promote and inhibit pathological gambling. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice. 2007;14:208–217. [Google Scholar]

- Moore SM, Ohtsuka K. Beliefs about control over gambling among young people, and their relation to problem gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Substance abuse, pathological gambling, and impulsiveness. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Validity of a gambling scale for the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000071589.20829.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Pathological gambling: Etiology, comorbidity, and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Concurrent and predictive validity of the Addiction Severity Index in pathological gamblers. American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16:272–282. doi: 10.1080/10550490701389849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Ammerman Y, Bohl J, Doersch A, Gay H, Kadden R, Molina C, Steinberg K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:555–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Litt MD, Kadden R, Ledgerwood DM. Do coping skills mediate the relationship between cognitive-behavioral therapy and reductions in gambling in pathological gamblers? Addiction. 2007;102:1280–1291. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Petry NM. Antisocial personality disorder is associated with increased severity of gambling, medical, drug and psychiatric problems among treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Addiction. 2005;100:1183–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Fava JS. Measuring the processes of change: applications to the cessation of smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:520–528. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project Match Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to clients heterogeneity: Project MATCH Posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Blaszczynski A. Impulsivity, personality disorders and pathological gambling severity. Addiction. 1998;93:895–905. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93689511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zack M. Development and psychometric evaluation of a three-dimensional Gambling Motives Questionnaire. Addiction. 2008;103:1110–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zack M, Collins P, Klein RM, Fragopoulos F. Subtyping pathological gamblers on the basis of affective motivations for gambling: Drinking problems, and affective motivations for drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:257–268. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield R. Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Lesieur HR, Breen RB, Stinchfield R, Lejuez CW. Using a Rasch model to examine the utility of the South Oaks Gambling Screen across clinical and community samples. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:465–481. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NE, Jain U, Spence W, Zangeneh M. Pathways to pathological gambling: Component analysis of variables related to pathological gambling. International Gambling Studies. 2008;8:281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Arseneault L, Tremblay RE. Impulsivity predicts problem gambling in low SES adolescent males. Addiction. 1999;94:565–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94456511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock J, Whelan JP, Meyers AW. Behavioral assessment of gambling: An application of the timeline followback method. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:72–80. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA. 1996;276:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, van der Maas HLJ, Huffort MR, Marlatt GA. Nonnormality and divergence in posttreatment alcohol use: Reexamining the Project Match data “another way”. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:378–394. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody GE, McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O’Brien CP. Sociopathy and psychotherapy outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:1081–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790340059009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfert E, Roland BD, Hartley J, Wang N, Franco C. Heart rate arousal and excitement in gambling: Winners versus losers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:311–316. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]