Abstract

Screening for HIV in the emergency department (ED) is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control. The relative importance of efforts to increase consent among those who currently decline screening is not well understood. We compared the risk characteristics reported by patients who decline risk-targeted, opt-in, ED screening with those who consent. We secondarily recorded reasons for declining testing and reversal of the decision to decline testing after prevention counseling. Of 199 eligible patients, 106 consented to testing and 93 declined. Of those declining, 60/93 (64.5%) completed a risk assessment. There were no differences in HIV risk behaviors between groups. Declining patients reported recent testing in 73.3% of cases. After prevention counseling, 4/60 (6.7%) who initially declined asked to be tested. Given similarities between those who decline or consent to testing, efforts to increase consent may be beneficial. However, this should be tempered by the finding that many declined because of a recent negative test. Emphasizing risk during prevention counseling is not a promising strategy for improving opt-in consent rates.

Keywords: Emergency Service, Hospital, Communicable Disease Control, Mass Screening, Preventive Health Services, Risk Factors, HIV seropositivity

Introduction

The HIV epidemic in the United States continues, and newly released figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that the annual transmission rate is higher than previously estimated. (1) Identifying individuals with undiagnosed HIV through expanded HIV testing in emergency departments is a central CDC recommendation. (2) The fact that many patients decline to be tested is one of the many barriers to expanded HIV testing.

Several studies have shown a higher prevalence of HIV among those who decline testing compared to those who consent to testing. (3-7) This suggests that those who decline HIV testing are at higher risk for HIV. Also, increasing consent rates by altering consent methodology can increase the identification of HIV-positive individuals. (8)

Despite the benefit of increasing consent rates among patients who are potentially infected, the relative benefit of adopting progressive consent strategies in resource-limited settings is unclear. Unless resources are sufficient to test all patients, it is possible that resources would be more optimally allocated to expand testing among those who readily consent rather than among those who currently decline. In addition, opt-out consent remains controversial and is prohibited by law or regulation in some locations. It may also be difficult to implement in settings that have not adopted universal screening practices; opt-out consent conceptually depends on the presence of a consistently applied care standard which the patient can decline. The central question upon which this preliminary investigation is centered is whether scarce administrative and operational resources are better used to expand screening within populations that readily consent for testing or to increase testing within populations that do not currently agree to testing.

We compared the HIV risk characteristics of patients accepting an HIV test to those declining an HIV test offered via conventional consent methods. We secondarily recorded reasons why patients declined testing and attempted to determine whether patients who initially declined testing would reverse that decision during formal risk-assessment and prevention counseling.

Methods

This was an observational study comparing the self-reported HIV risk behaviors between those patients who declined ED HIV testing yet agreed to prevention counseling and those who consented to HIV testing. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

The study was conducted in the ED of an urban tertiary referral hospital with an annual ED census of approximately 85,000 patients. An HIV screening program has offered confidential, voluntary opt-in HIV testing and counseling services to ED patients for the last ten years. (9) The ED screening program is funded and regularly reviewed by the state health department. During the year that this study took place, the program conducted 3,888 tests with a positivity rate of 1.0%. The program was staffed 24 hours per day by dedicated counselors. Counselors were medical or nursing students, or adjunct health professionals trained according to the CDC guidelines for client-centered HIV prevention counseling. (10) ED patients were offered testing when clinical staff identified symptoms suggestive of HIV, when clinical staff and/or counselors identified factors suggesting higher than baseline likelihood of undiagnosed HIV infection, or as a result of self-request.

The program uses a traditional opt-in consent approach requiring a patient signature. During the study period, the program used conventional HIV assays with delayed result availability. In conjunction with testing, patients received formal risk-assessment and prevention counseling using a structured, questionnaire-driven interview seeking to promote an individualized, achievable plan for risk reduction. An electronic clinical record of patient information obtained during these encounters is maintained in a comprehensive electronic system designed specifically for the HIV testing program. As part of the screening program’s usual practice, patients who declined testing also receive prevention counseling to the degree possible given patients’ willingness to participate; detailed records of such interactions for patients who decline HIV testing were not maintained by the clinical program, but were encompassed in the research protocol.

The study included two groups of participants from ED patients aged 18 years or older: i) those who declined HIV testing but who consented to have the details of their risk reduction counseling recorded for research purposes, and ii) patients consenting to an HIV testing and counseling. All participants, both those consenting to testing and those declining testing but consenting to research participation, were approached during the same time periods.

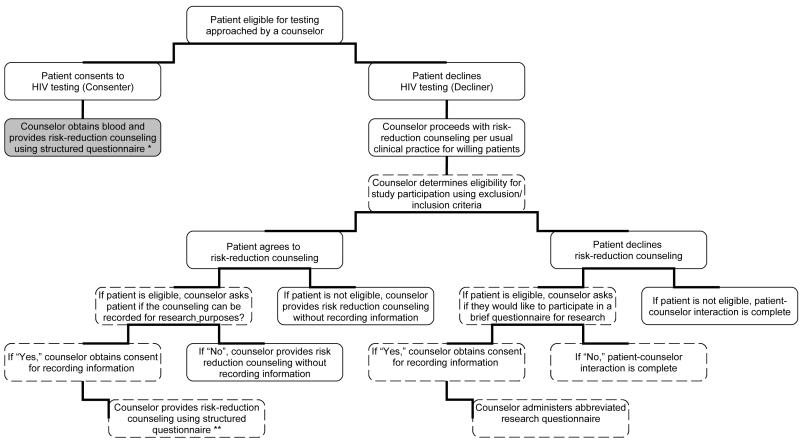

Patient flow through the study is described in Figure 1. Patients were screened for eligibility by the seven counselors in our program during 22 selected periods. Five study periods took place overnight (between midnight and six am), seven were during the weekend (between Friday at six pm and Monday at six am), and ten were during weekdays (Monday to Friday, between six am and midnight). For patients who declined testing, counselors sought informed consent for this study. It was explicitly stated that data would be recorded without identifiers. Patients who declined testing but who consented to have their responses to risk assessment recorded received prevention counseling driven by a structured questionnaire in the same manner as provided to patients who consented to testing. Patients refusing counseling were asked to complete a brief, interviewer-led risk questionnaire. Data for patients who consented to testing were obtained from the program’s electronic record.

Figure 1. Screening and Enrollment Flow Chart.

Steps in patient screening and study enrollment are as shown. The shaded area represents the clinical arms for which research data were obtained from the clinical encounter, while dashed boxes represent the research arms for which data were obtained solely for the purposes of the research. * = “Consenters” in our study ** = “Decliners” in our study

The primary outcome measure was HIV risk as assessed on 15 self-reported behaviors or epidemiological factors associated with increased likelihood of HIV infection. Secondary measures included the reasons testing was offered, reasons for refusal, and the number of patients who reversed their decision and agreed to testing during counseling.

Data were managed using Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), and they were analyzed using SPSS v 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il). Data are described using median and range for continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U-test and Fisher’s Exact Test were used to compare groups.

Results

Between April 28 2008 and June 4 2008, 213 patients were targeted for HIV screening during study periods (Figure 1). Of these, the invitation to testing could not be completed in 9 cases. Four patients were less than 18 years of age, and were excluded. One additional patient did not have a completed risk questionnaire and was excluded. There were 106 eligible patients consenting to testing with risk information. Of the 93 patients who initially declined HIV testing, 60 consented to have their risk assessment recorded for research purposes. None of the patients who declined HIV testing and risk assessment refused risk-reduction counseling. Of the 60 patients who initially declined testing 4 (6.7%, 95% CI 2.2%-17%) reversed their decision during subsequent risk-assessment and prevention counseling. For analysis purposes, these patients were included with decliners.

Overall, the median age was 28 years (range 18 to 70 years), 51.8% were female, 62.7% were black and 1.8% were self-identified as Hispanic. The 60 decliners and 106 consenters are described in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between groups at the 5% level, although consenters were more likely to live in poverty (p=0.06) and be female (p=0.053). One patient was found to be HIV positive as a result of testing during the study periods.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients consenting to HIV testing and patients declining testing. Data are given as median and ranges or frequencies and percentages.

| Consenters N=106 |

Decliners N=60 |

P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | (median/range) | 27 (18-70) | 28 (18-57) | 0.578 |

|

| ||||

| Sex | Male | 44 (42.3) | 35 (58.3) | 0.053 |

| Female | 60 (57.7) | 25 (41.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Race | White | 38 (35.8) | 21 (35.0) | 0.624 |

| Black | 65 (61.3) | 39 (65.0) | ||

| Other, mixed or unknown race | 3 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.534 |

|

| ||||

| SES | No access to primary care | 47 (46.1) | 32 (53.3) | 0.418 |

| At or below the poverty level | 69 (69.0) | 31 (53.4) | 0.060 | |

|

| ||||

| Reason for offer |

Patient request | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.802 |

| Clinical staff referral based on symptoms or illness |

1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Clinical staff referral based on risk | 8 (7.6) | 2 (3.3) | ||

| Counselor identified risks | 95 (89.6) | 57 (95.0) | ||

Statistical testing used the Mann-Whitney U-test or Fisher’s Exact test as appropriate.

The epidemiological and behavioral risk factors for HIV are shown in Table 2. We found no statistically significant differences between the patients who consented to HIV testing versus those who declined at the 5% level, although there was a trend towards increased rates of prior HIV testing among those who consented to testing versus those who declined testing (p=0.087).

Table 2.

Self-reported risk profiles of patients consenting to and declining an HIV test. Data are given as frequencies and percentages; statistical testing used Fisher’s Exact test.

| Consenters N=106 |

Decliners N=60 |

P- Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MSM | 3 (2.8) | 1 (1.70) | 1.000 |

|

| |||

| >1 partner in past year | 55 (51.9) | 28 (46.7) | 0.628 |

|

| |||

| Sex with an at risk partner | 34 (32.1) | 18 (30.0) | 0.862 |

|

| |||

| IDU who do not share needles | 4 (3.8) | 2 (3.3) | 0.885 |

| IDU who share needles | 4 (3.8) | 1 (1.7) | |

|

| |||

| Crack use in past year | 11 (10.4) | 7 (11.7) | 0.800 |

|

| |||

| Prior HIV test (ever) | 84 (79.2) | 54 (90.0) | 0.087 |

|

| |||

| Institutionalized For Drugs Or Alcohol more than 1 year previously |

7 (6.6) | 4 (6.7) | 1.000 |

| Institutionalized For Drugs Or Alcohol less than 1 year previously |

10 (9.4) | 5 (8.3) | |

|

| |||

| Institutionalized For Psychiatric Condition more than one year previously |

12 (11.3) | 5 (8.3) | 0.725 |

| Institutionalized For Psychiatric Condition less than one year previously |

8 (7.5) | 3 (5.0) | |

|

| |||

| Homeless more than one year previously | 16 (15.1) | 13 (21.7) | 0.524 |

| Homeless less than one year previously | 16 (15.1) | 9 (15.0) | |

|

| |||

| Incarcerated more than one year previously | 45 (42.5) | 25 (41.7) | 0.956 |

| Incarcerated less than one year previously | 24 (22.6) | 15 (25.0) | |

Patients who declined testing were asked the reasons they did not want a test. Patients could give multiple responses. Forty-four patients claimed a prior test (73.3%), 21 denied risk (35.0%), 17 (28.3%) preferred not to be tested for defined reasons (did not want venipuncture, afraid of the result, or preferred alternative, rapid or anonymous testing), 2 (3.3%) were in too much pain or were nauseous, and 3 (5.0%) indicated the environment was not acceptable. There were 11 (18.3%) patients who indicated other reasons for refusing testing.

Since a large percentage of patients in our study (73.3%) cited a prior negative test as a reason for declining testing, we chose to secondarily explore the presence of risk factors since this last test, as reported by each patient. Of the 44 patients citing a prior test as a reason for declining testing, 6 reported having a test in the past month with results pending, 14 reported a negative test in the prior 3 months, 22 reported a negative test more than 3 months previously, and two subjects reported being a blood donor within the past 3 months. Twenty-three patients (52.3%) self-reported ongoing HIV risk more recent than their last test. Ongoing risk behaviors were vaginal, anal or oral sex in the absence of always using barrier methods with either multiple partners (N=19), at-risk partners (men having sex with men, previously incarcerated individuals, injection drug users, individuals with sexually transmitted infections, or HIV infected individuals; N=6), or during the exchange of drugs and/or money for sex (N=3). No patients in this group reported intravenous drug use within the past 12 months.

Twenty-one patients (35%) declined testing citing they were not at risk, despite the fact that they were approached as part of a targeted screening program. While none of these patients reported the traditional risk factors of being men who have sex with men or injection drug users, many had other substantial risk factors. For example, four reported having multiple partners in the past year, five were sexually active with at risk partners, one used crack, four had been institutionalized for psychiatric, drug, or alcohol abuse problems, seven had been homeless, and nine had been incarcerated. Only 3 of the 21 patients who declined testing because they believed they were not at risk for HIV reported no factors potentially associated with HIV risk.

Discussion

This study suggests that the behavioral and epidemiological HIV risk of those who decline conventional testing is no different than of those who consent. If the risk profile is reasonably correlated with HIV positivity, then missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis likely exist among those who are offered yet decline testing. This is consistent with prior studies (3-7) and generally supports the need for augmented voluntary testing using progressive consent methods, such as the “opt-out” method currently recommended by the CDC. (2)

This primary finding remains tempered by the limitations of our current knowledge. We do not know the actual proportion with undiagnosed HIV among declining patients in populations such as ours. It is possible that the association between self-reported risk and HIV positivity are not the same for those who consent to testing as those who decline testing. For example, the accuracy of self-reports could vary between groups. More likely, we found that many who declined testing (73.3%) did so on the basis of a recent negative test, suggesting a new diagnosis is less probable. If such patients are unlikely to be infected, then increasing consent rates among this population might be of little benefit or be less beneficial than applying resources to expanded testing among those who readily consent with a conventional approach. This raises the question of what circumstances constitute “appropriately” declined testing. The incidence rate of HIV infection among those with a prior negative test is not known in a setting such as ours. Our exploratory secondary analysis suggested that approximately half of those declining because of prior testing reported risk behaviors occurring since their most recent negative test. A more detailed understanding of the interaction between prior testing, ongoing risk, HIV positivity and consent methods is needed to address these issues. There remains a need for further comparative study of the relative effectiveness of progressive consent methods in settings where HIV is not highly prevalent.

The finding of no differences in risk between those ED patients who decline testing and those who consent should also be tempered by our sample size. While our findings do support the assertion that risk for HIV exists among those who decline, our sample size is not sufficiently large to conclude to that there are no differences between groups. Indeed, even with our small sample, some differences did tend toward significance. Therefore, a larger study would be able to more fully evaluate differences in risk between patients consenting to HIV testing and those who do not.

In contrast to our findings of similarity between those who consent to and those who decline testing, several other studies have found greater HIV prevalence among patients who decline testing. (3-7) This could be due to the fact that many of these studies occurred at a time when acceptability of testing and reasons for declining testing may have been quite different than is typical of today’s experience. Additionally, none of these studies explored HIV risk in EDs, and there may be inherent differences among decliners in different health care settings. The presence of a prior test as a predominant reason for refusal in our study also contrasts with other experiences from both ED and STD clinic settings where decliners were more likely to deny risk as a reason for refusal. (5;11) These differences could be due to the varying methods of screening, setting differences, or the duration of operation of screening programs.

Recommendations for non-targeted and universal screening are based on the finding that selecting patients according to their risk fails to include all patients with undiagnosed HIV. (2) Although this shortcoming of targeted testing has most often been attributed to failure of patients to disclose their risk behaviors, we found the frequency of self-reported risk to be surprisingly high (85.7%) even among patients who declined testing because they believed they were not at risk. This further demonstrates that failure to appreciate reported risk is also a barrier to expanded testing.

Risk assessment and risk-reduction counseling have been criticized as a resource barrier and have been labeled as stigmatizing. (2) However, they may also be associated with a number of benefits. (12) A secondary objective of our study was to determine whether or not patients who initially declined testing reversed that decision as a result of risk-reduction counseling. We hypothesized that many patients would come to appreciate their risk as a result of counseling and then be more amenable to testing, providing one approach to increasing consent rates using a traditional opt-in method. Although the rate at which this occurred (6.7%) was not negligible, our results suggest that risk-assessment and risk-reduction counseling cannot be viewed as a practical method of significantly increasing consent rates for HIV testing.

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. We may have failed to find a difference between patients who consented to HIV testing and those that declined testing because of small sample size. Also, the extent to which the individuals who consented to participate in our study represent the entire population of patients that decline HIV testing is unknown; the risk profile of those not participating in this study cannot be ascertained. The study itself may have influenced the consent rate for HIV testing. For example, counselors may have been more willing than usual to accept a patient’s decision to decline testing and continue with study enrollment rather than encourage testing. However, the consent rate during the study was commensurate with our experience when the study was not ongoing. Our analysis of ongoing risky behavior since the most recent negative HIV test was exploratory; the information on timing of risk behaviors was general and self-reported prior testing history was subject to recall and reporting bias. All results should be tempered by the self-reported nature of risks.

In conclusion, patients who declined targeted, opt-in HIV testing had behavioral and epidemiological risks equivalent to those that consented. This supports the need for increasing consent rates for testing as might be achieved using the progressive consent methods recommended by the CDC. However, any expected benefit of increasing consent rates must be tempered with the knowledge that most patients who declined reported a prior negative test as the reason for their consent decision. There is likely an important interaction between methods for increasing consent rates, prior testing behavior, and the rate of incident infection in a given population. Risk reduction counseling was rarely associated with reversal of the initial consent decision, even among patients with self-reported risk, and is unlikely to represent an efficient method to increase consent rates.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The clinical program described in this report was supported by the Ohio Department of Health and the Cincinnati Health Network. The research was supported in part by K23AI068453 from the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presentation: This study was presented at the 2008 National Summit on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis and Access to Care in Arlington, VA in November 2008.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nitin D. Ubhayakar, Department of Emergency Medicine University of Cincinnati College of Medicine ubhayan@email.uc.edu.

Christopher J. Lindsell, Department of Emergency Medicine University of Cincinnati College of Medicine lindsecj@ucmail.uc.edu.

Dana L. Raab, Department of Emergency Medicine University of Cincinnati College of Medicine raabd@ucmail.uc.edu.

Andrew H. Ruffner, Department of Emergency Medicine University of Cincinnati College of Medicine ruffneah@ucmail.uc.edu.

Alexander T. Trott, Department of Emergency Medicine University of Cincinnati College of Medicine trotta@ucmail.uc.edu.

Carl J. Fichtenbaum, Infectious Disease Center University of Cincinnati College of Medicine fichtecj@ucmail.uc.edu.

Michael S. Lyons, Department of Emergency Medicine University of Cincinnati College of Medicine lyonsme@ucmail.uc.edu.

References

- 1.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. quiz CE1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groseclose SL, Erickson B, Quinn TC, et al. Characterization of patients accepting and refusing routine, voluntary HIV antibody testing in public sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex.Transm.Dis. 1994;21:31–35. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hull HF, Bettinger CJ, Gallaher MM, et al. Comparison of HIV-antibody prevalence in patients consenting to and declining HIV-antibody testing in an STD clinic. JAMA. 1988;260:935–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones JL, Hutto P, Meyer P, et al. HIV seroprevalence and reasons for refusing and accepting HIV testing. Sex.Transm.Dis. 1993;20:334–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plitt SS, Singh AE, Lee BE, et al. HIV seroprevalence among women opting out of prenatal HIV screening in Alberta, Canada: 2002-2004. Clin.Infect.Dis. 2007;45:1640–1643. doi: 10.1086/523730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstock H, Dale M, Linley L, et al. Unrecognized HIV infection among patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Am.J.Public Health. 2002;92:280–283. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JH, Mitchell B, Nolt B, et al. Targeted opt-in vs. routine opt-out HIV testing in an STD clinic. 1999.

- 9.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ledyard HK, et al. Emergency department HIV testing and counseling: an ongoing experience in a low-prevalence area. Ann.Emerg.Med. 2005;46:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50:1–57. quiz CE1-19a1-CE6-19a1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown J, Kuo I, Bellows J, et al. Patient Perceptions and Acceptance of Routine Emergency Department HIV Testing. 2008;123(Suppl. 3) doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtgrave DR. Costs and consequences of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendations for opt-out HIV testing. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]