Abstract

Background

Mentorship is considered central to physician success, and yet relatively few physicians report having formal mentors. Ever-increasing demands on physician time as well as multiple personal and professional responsibilities, make it challenging to find and sustain mentoring relationships. These challenges may be even greater in palliative medicine, a field with few mid-level to senior faculty and in which the supply of physicians is inadequate to meet the anticipated demand.

Discussion

In this article, we describe the attributes of the “ideal” mentor and the roles mentors commonly play in a protégé's career. We then discuss a framework for optimizing one's chance of fostering mentoring relationships. We conclude by discussing the evolution of and transitions in mentoring relationships, as well as how one might transition from protégé to mentor.

Introduction

Mentorship is considered crucial to academic success and career enhancement for physicians.1–4 Within academia, mentorship traditionally involves assistance in teaching skills, research, and career advancement, as well as with learning to navigate institutional and academic culture. Both inside and outside academia, mentors provide guidance in clinical practice, program development, leadership, business practices, conflict resolution and team building. Across settings, mentoring contributes to higher career satisfaction3,5–7 ; increased self-confidence in professional development, education and administration1–3; improved sense of community2,4,5,8,9; and greater productivity and success.1,3,7,10 Mentored individuals are more likely to pursue a career in academic medicine or research,1 and those with mentors may be more likely to be promoted.1, 9 Lack of mentorship has consistently been identified as a barrier to completing scholarly projects, publication1 and is frequently perceived to be one of the most significant impediments to academic physicians' careers.1,3,7,11–13

Despite the apparent benefits of mentoring, only one third14 to one half3 of faculty report having a mentor; in some fields, the prevalence is as low as 20%.1 Mentoring may be more challenging within palliative medicine, a field in which the supply of physicians is inadequate15 and in which there is a relative dearth of senior and mid-level faculty. In institutions lacking senior palliative medicine faculty, junior physicians may have few opportunities for local mentoring within their specialty. While remote mentors can support personal and career development, advise on projects, and serve as advocates at the national level, they are unable to promote protégés within their local institutions, making it difficult for junior faculty to garner local visibility and credibility. Additionally, the shortage of senior physicians often thrusts junior physicians into leadership positions beyond their skills. The paucity of palliative medicine physicians may compel each physician to juggle multiple roles: clinician, administrator, educator, and researcher. Positions with so many demanding roles can quickly become “career-killer jobs” that result in physician burnout. The implications to the field are equally distressing: failure to realize fully the passion and skills of junior physicians and loss of intellectual capital.

In this article, we review selected tenets of mentoring, specific strategies for fostering successful mentoring relationships, and how mentoring relationships may evolve, transition, or conclude over time. We end by discussing the transition from protégé to mentor.

The Traditional Mentor: A Definition

Zerzan16 describes a mentor as “someone of advanced rank or experience who guides, teaches and develops a novice.” The term, mentor, derives from the Greek myth of Odysseus, who entrusted the care of his son, Telemachus, to his friend, Mentor, when he left to fight in the Trojan War. Mentor served as a teacher and transitional figure to Telemachus over many years, guiding him on his journey to independence.17 At work, mentoring has been recrafted as “ … a dynamic reciprocal relationship in a work environment, between two individuals where, often but not always, one is an advanced career incumbent and the other is a less experienced person. The relationship is aimed at fostering the development of the less experienced person.”18 The traditional mentoring relationship is ideally reciprocal, mutually-beneficial, and both personal and professional.13

Mentors: Attributes and Roles

An optimal mentoring relationship is much more than simply a means to career advancement. A mentor's goals, values, and approach to the world, as well as such amorphous qualities as interpersonal chemistry and compatibility, are as important as the roles a mentor plays in career promotion. The literature largely describes mentoring and mentors in an idealized way. However, real-life mentors are people who suffer personal and career setbacks like everyone else. Below, we discuss “ideal” mentors, including both their interpersonal and relational attributes and the key roles they might play in advancing a protégé's career. Later, we elaborate on developing and fostering “good enough” mentoring relationships that address the multiple career and personal needs of the protégé.

Relational attributes of an ideal mentor

An ideal mentor demonstrates a solid dedication to the mentoring process8 and a genuine desire to build a reciprocal working relationship with the protégé. Such dedication requires that the mentor recognizes the protégé's potential13 and wishes to promote his or her career.

The ideal mentor is credible,8 trustworthy,19 reliable,13 altruistic, generous, and possesses qualities the protégé may wish to emulate. He or she may serve as an “academic parent,” working to support the personal and professional growth of the protégé.13 Such mentors are able to distinguish their own agenda from that of the protégé, keeping the protégé's goals in the forefront while supporting his or her efforts to weave a uniquely personal path. Although mentoring is mutually beneficial, mentors who view their work with protégés primarily as a means of promoting their own career are usually worth avoiding.

An ideal mentor does not direct the protégé actions but instead works to enhance the protégé's ability to see and reflect productively on the breadth of existing possibilities. A mentor presents opportunities and highlights challenges that the less experienced protégé might not see.20 An experienced mentor is able to provide optimal tension between challenging and supporting the protégé, balancing efforts that stimulate the protégé to reflect, learn, and grow with acts of reassurance, affirmation and support.21,22 Such attributes require exceptional emotional intelligence and capacity for empathy.13,19

Mentoring roles

Tobin summarized seven roles a mentor might play in a protégé's career.23

As teachers, mentors provide information regarding institutional politics and procedures, as well as guidance about time management, teaching, research, and leadership.19,21,23,24

As sponsors, mentors advocate for protégés in the professional world, adding to their visibility and credibility by expanding their local and national collegial network.13,14,19,21,23,24

As advisors, mentors are guides and counselors14 who help protégés navigate their careers23 and work toward their own definitions of success. Mentors provide insights on who a protégé is and where he or she is going.8,21 As such, mentors are catalysts for growth,23 helping the protégé develop skills and self-reliance.13,14,23,24

As agents, mentors protect protégés,24 helping them overcome obstacles and providing protection from excessive institutional demands.

As role models, mentors demonstrate behavior protégés wish to emulate.19,23 Without this, good “chemistry” between mentor and protégé is unlikely.13

As academic coaches, mentors provide instruction, training, strategic advice, and motivation. A skilled mentor is able to sense when the protégé needs encouragement, guidance, or even a shove.4,13

As confidantes, mentors are empathic listeners, offering insights23 and providing emotional and psychological support.8,21

Network Mentoring: It Takes a Village

Few physicians will find one mentor who is able to meet all of their mentoring needs. Additionally, mentoring needs evolve as careers progress and roles change. Therefore, more liberal and inclusive approaches to developing successful mentoring relationships are needed to address limited resources, faculty time constraints, and the need for geographically remote mentors. Peer mentoring and mosaic mentoring provide helpful frameworks for building a successful mentoring network (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of Mentoring Relationships

| Mentoring relationship | Definition | Key features and examples | Advantages and disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional mentoring | Mentor is someone of more experience, guiding and teaching a novice | One-on-one relationship with a senior guide invested in the protégé's career |

Advantages: —Demonstrated benefits to career enhancement and satisfactiona |

| Ex. Research mentor |

Disadvantages: —Difficult to finda —Limitations of individual mentorb |

||

| Peer mentoring | Mutual relationships between individuals at a similar career levelc | Parties alternate being giver and receiver, mentor and protégé |

Advantages: —Enhanced mutuality —Deemphasizes hierarchyb |

| Special Peer relationship | Colleagues who are personal academic advisors, collaborators, friends, and confidantes | Relationship broad in scope | —Allows both parties to learn and practice mentoring skills —may be more enduringc |

| Ex. Faculty at different institutions who coach and support one another |

Disadvantages: —Competition for resources and achievement may exist between faculty at the same level |

||

| Information Peer | Friendly resource for information or connection | Ex. Someone who provides introduction to mutual colleagues | —Lack of senior guide could allow for unchecked missteps |

| Collegial Peer | Collaborator | Relationship may be limited to project-specific interactions | —Requires high level of confidentiality |

| Collaborative peer mentoring | Similar to peer mentoring, but may involve groups rather than dyads. | Can be formal or informal. Groups may collaborate on projects, set learning goals, or provide critical assistance with one another's work |

Advantagesb,d: —Builds collegial network —Benefit from multiple perspectives |

|

Disadvantages: —Difficult to organize —Parsing out projects in a large group may result to competition for participation, authorship, etc. |

|||

| Facilitated peer mentoring | A small group works on an agreed upon project with the guidance of a senior facilitator and mentor | Ex. Four junior faculty working together on a paper, with a facilitator mentor |

Added Advantages:d —Multiple faculty benefit from the mentorship of a single senior faculty mentor —Structured, and time- or project-limited |

| Mosaic mentoring | Protégé is encouraged to construct a mentoring community | Ex. One individual has separate mentors for leadership and education, a project mentor for a specific paper, and a peer mentor for an education project |

Advantages: —Multiple mentors with varied skills and at varied levels —Less reliance on one person —Creates broader collegial network |

|

Disadvantages: —May lack big-picture oversight |

Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A: Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1103–1115.

Pololi LH, Knight SM, Dennis K, Frankel RM: Helping medical school faculty realize their dreams: An innovative, collaborative mentoring program. Acad Med 2002;77:377–384.

Hitchcock MA, Bland CJ, Hekelman FP, Blumenthal MG: Professional networks: The influence of colleagues on the academic success of faculty. Acad Med 1995;70:1108–1116.

Pololi L, Knight S: Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? Jo Gen Intern Med 2005;20:866–870.

Peer mentoring

In peer mentoring, each party has the experience of being the giver and the receiver, allowing both to benefit from mentoring while developing mentoring skills themselves.25 As such, peer-mentoring relationships may be more enduring than traditional senior–junior mentoring relationships.24,26 They have the virtue of enhancing socialization while simultaneously providing guidance in academic work and in navigating a shared academic world. Through peer mentorship, physicians are able to extend their collegial networks to local, regional, and national colleagues.24

Different categories of peer mentors have been described.24,26,27 One category is the collegial social relationship24,27 or special peer relationship24,26 in which colleagues serve as friends, personal and academic advisors, peer mentors, and project collaborators. For example, two physicians with similar leadership roles at different institutions may serve as mutual confidantes, coaches, and task-specific mentors to one another, alternately sharing both mentor and protégé roles depending on each one's needs over time. Examples of more limited peer relationship categories are collegial task relationships,24,27 including the information peer24,26 and the collegial peer.24,26 An information peer is a friendly resource for knowledge, insights, or connections. The collegial peer is someone with whom one partners in shared creative or academic ventures. A collegial peer relationship may be limited to collaboration on a specific project.24,26,27

In addition to dyadic peer mentoring relationships, group mentoring models have proven successful.5 Such groups may work together on specific projects or toward broader academic or personal goals. These groups can be informal and similar to the “special peer” relationship described above, or they can be more formal and structured, as with facilitated peer mentoring.25,28,29 In facilitated peer mentoring, a small peer group works collaboratively toward an agreed upon goal with the guidance of a senior “facilitator mentor” who aids in skills acquisition and provides project-specific academic guidance. For example, four peers collaborate in writing a paper mentored by a designated senior faculty. Facilitated peer mentoring enhances the benefits of peer mentoring by providing added structure and guidance, while extending the influence of a limited resource, the senior mentor.28–30

Mosaic mentoring

Mosaic mentoring19 or multiple mentoring25 involves the protégé seeking a team of mentors, with each mentor performing a different role in the protégé's professional development. Higgins and Kram31 refer to these as “relationship constellations,” emphasizing that individuals are best served by relying on a community of mentors for developmental support. Careers are multifaceted and fluid, and people are complex. Thus, it is unrealistic to think that one mentor could support a protégé's every need over time. Having multiple mentors has been associated with both job satisfaction and satisfaction with mentoring,6 confirming the notion that mosaic mentoring is not “second best” but is instead optimal.6,31

In mosaic mentoring, one mentor may help with career planning, another with leadership, and others with certain specific academic work projects. Mentors may come from different fields or disciplines. The principle of mosaic mentoring is that the function each mentor fills for the protégé is as important as the individual relationship.13,19 For example, a junior physician who is the director of both a clinical and an educational program may have separate mentors for leadership, education administration, teaching, and overall career planning. The junior physician thus has access to expertise in multiple areas. Because no one mentor is expected to “do it all,” the mentoring role is also more approachable and less time-consuming for the mentor. Ideally, the protégé's mentoring community forms a well-fitting matrix of support.

Finding and Keeping a Mentor

Management research demonstrates that personality characteristics can influence one's likelihood of receiving mentoring.32 Individuals with an internal locus of control,31 high self-monitoring skills and emotional stability are more active in seeking mentoring relationships, which in turn contributes to receiving mentoring and to career success.1,32 The very fortunate might stumble upon “informal mentoring,”13,22,28 which occurs serendipitously when individuals are drawn together by mutual interests. However, for most people, a mentor is someone who must be sought after and with whom a relationship must deliberately be forged.12,13,16 Mentoring relationships are sustained and grow only through meticulous effort.13,16

Identifying individual goals and needs

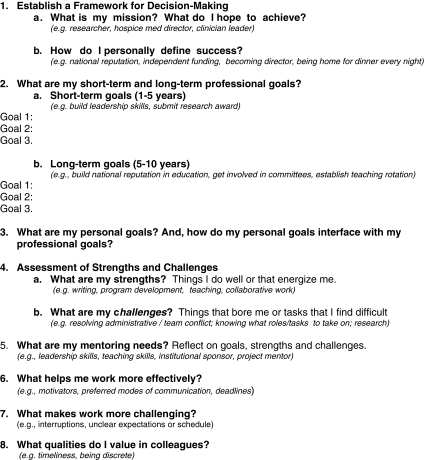

Before seeking a mentor, the aspiring protégé should engage in self-assessment. What are your goals and priorities? Your strengths and challenges? (Fig. 1).12,19,33 Strengths can be defined both as areas in which one excels and as tasks one finds engaging and energizing.33 Challenges or weaknesses include activities that sap one's energy or that one finds deflating or dull. Once goals, strengths, and weaknesses are defined, identify the areas in which you most require mentoring12: career guidance, research assistance, leadership, work–life balance, and/or personal growth. Failure to be honest with yourself and your mentor about your personal and professional goals will inhibit the relationship.33 In reflecting on the attributes of a desired mentor, reflect on work habits and relational qualities that best match your needs and habits.

FIG. 1.

Mentoring self-evaluation tool.

Next make a list of individuals who have the knowledge and skills you wish to acquire or who can otherwise help you as a mentor.12 Search broadly, asking others whom they would recommend and becoming familiar with the work of mentor candidates. Approach the potential mentor with a deliberate request; be specific about the kind of help you are requesting.12 Consider an invitation that allows the potential mentor a graceful means of declining (e.g., “I've enjoyed meeting you and learning more about your work. I think I could learn a lot from working with you more closely. Would you consider mentoring me in my new leadership role? I understand that you are very busy and that it may not be possible. If you are unable to mentor me, perhaps we could think together about who else might be a good resource for me.”)

Fostering the relationship

Zerzan and colleagues16 applied the corporate principle of “managing up” to mentoring, meaning that protégés must be motivated and self-aware, taking responsibility for the relationship by learning both their own and the mentor's needs and limitations.16 How frequently will meetings occur? How will progress be defined? What are each individual's responsibilities? Show appreciation by being well-prepared for meetings and demonstrating basic manners (e.g., timeliness) so that the mentor's time and energy are used efficiently.12 Being prepared also means that the protégé is receptive to feedback16 and open to talking with the mentor when things aren't going well.

Common pitfalls in mentoring relationships include ongoing competition between mentor and protégé as well as misunderstandings regarding roles, boundaries, or goals of the relationship. Your mentor is neither your parent nor your savior. Similarly, protégés are not their mentors' clones and need not always heed their advice. Maintaining open communication about the relationship's direction19 and building in time to review processes and give mutual feedback can help circumvent these pitfalls.

The Evolution of Mentoring Relationships

Hitchcock and colleagues24 describe four stages in the evolution of mentoring relationships. A mentor is selected during the “initiation stage” (6–12 months), which is followed by the “protégé stage” (2–5 years), the “break-up stage,” and the “lasting friendship stage.” Some relationships end gradually as the protégé achieves independent recognition or funding. Some end more abruptly due to career changes, conflict, or the relationship ceasing to be of value.33 A successful “break-up” that results in “lasting friendship” can only occur when the relationship is redefined in a mutually agreeable manner.19,24

Sometimes mentor–protégé relationships are not successful and need to be terminated.33 Reasons for mismatch might include personality differences, conflict, or ongoing competition. In healthy relationships there would ideally be an implicit “no-fault” policy in which both parties can terminate the relationship at any time without risk of career harm.33 In more toxic scenarios, such as the misappropriation of credit (e.g., the mentor takes credit for the protégé's work) or issues in which one's job or credibility may at risk (e.g., sexual harassment), a protégé may need to ascend the chain of command to solicit help exiting the relationship.

Transitioning to Being a Mentor

Why mentor?

The benefits of mentorship to the protégé are clear. But what do mentors gain, besides added responsibility and commitment? Passing on knowledge, skills and wisdom to the next generation is gratifying.34,35 A mentor engaged in projects with a protégé is often able to accomplish more with the protégé than he or she could alone, and the mentor is able to share in the protégé's successes.23 Protégés challenge their mentors, helping them to stay abreast of new developments and to expand their own collegial network.19 Perhaps most importantly, building such a personal and productive relationship is rewarding and often leads to lifelong friendships.19

Giving forward

Junior faculty are sometimes reluctant to become mentors. They may be uncertain about what successful mentoring entails and reluctant to undertake the responsibility. With multiple competing imperatives, time is difficult to find. Additionally, potential mentors may underestimate what they have to offer, fearing that they lack both real world knowledge and specific mentoring skills.28

Physicians at all levels have much to offer peers and junior colleagues. First, protégés benefit from cultivating mentors at both junior and senior levels, as the skills of one often complement those of the other. Junior physicians are closer to the protégé's career stage and may have more time. Having both senior and junior mentors allows the protégé to get needed guidance across the spectrum of work and personal goals.13,14,16 Additionally, junior physicians are commonly advised to seek mentors who are a half-generation ahead23—someone with enough experience to have gained wisdom and insight, to have made connections, and to be positioned to sponsor more junior colleagues within the institution or field. Ideally, mentors are past concerns of direct competition with a protégé yet not so far ahead that they have lost sight of the protégé's needs.23 To assist junior and mid-career faculty in learning mentoring skills, academic centers are increasingly creating faculty development programs.4,9,34–38 Mentors who have participated in such programs report improved skills, increased confidence, and an enhanced sense of community.38

Conclusion

Ever-increasing demands on physician time, geographic isolation from more senior faculty in the field, and multiple conflicting responsibilities make finding alternatives to the dyadic mentoring relationship essential. Having a constellation of mentors at different levels and with different skills is a viable and user-friendly alternative to seeking that one “academic parent” described in traditional mentoring. One's attitude and approach is essential to the success of any mentoring relationship, whether with peers or more senior physicians. In medicine, intellectual capital is a crucial asset. Developing and sustaining mentoring relationships benefits not only a protégé's career but also to the growth of our field.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Carey is supported by a Geriatric Academic Career Award From the Health Resources and Services Administration (Grant number 1 K01 HP00028-01).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Sambunjak D. Straus SE. Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wingard DL. Garman KA. Reznik V. Facilitating faculty success: outcomes and cost benefit of the UCSD National Center of Leadership in Academic Medicine. Acad Med. 2004;79(10 Suppl):S9–11. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200410001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palepu A. Friedman RH. Barnett RC. Carr PL. Ash AS. Szalacha L. Moskowitz MA, et al. Junior faculty members' mentoring relationships and their professional development in U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 1998;73:318–323. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199803000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morzinski JA. Diehr S. Bower DJ. Simpson DE. A descriptive, cross-sectional study of formal mentoring for faculty. Fam Med. 1996;28:434–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pololi LH. Knight SM. Dennis K. Frankel RM. Helping medical school faculty realize their dreams: An innovative, collaborative mentoring program. Acad Med. 2002;77:377–384. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasserstein AG. Quistberg DA. Shea JA. Mentoring at the University of Pennsylvania: results of a faculty survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:210–214. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0051-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levinson W. Kaufman K. Clark B. Tolle SW. Mentors and role models for women in academic medicine. West J Med. 1991;154:423–426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berk RA. Berg J. Mortimer R. Walton-Moss B. Yeo TP. Measuring the effectiveness of faculty mentoring relationships. Acad Med Jan. 2005;80:66–71. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200501000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried LP. Francomano CA. MacDonald SM. Wagner EM. Stokes EJ. Carbone KM. Bias WB. Newman MM. Stobo JD, et al. Career development for women in academic medicine: Multiple interventions in a department of medicine. JAMA. 1996;276:898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Illes J. Glover GH. Wexler L. Leung AN. Glazer GM. A model for faculty mentoring in academic radiology. Acad Radiol. 2000;7:717–724. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(00)80529-2. discussion 725–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborn EH. Ernster VL. Martin JB. Women's attitudes toward careers in academic medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Acad Med. 1992;67:59–62. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrell SE. Digioia NM. Broderick KB. Coates WC. Mentoring for clinician-educators. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1346–1350. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson VA. Palepu A. Szalacha L. Caswell C. Carr PL. Inui T. “Having the right chemistry”: A qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:328–334. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramanan RA. Phillips RS. Davis RB. Silen W. Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112:336–341. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A Report Prepared for the Bureau of HIV/AIDS, Health Resources and Services Administration. Vol. 2010. Rensselaer, New York: Center for Health Workforce Studies, School of Public Health, University of Albany; 2002. The Supply, Demand, and Use of Palliative Care Physicians in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zerzan JT. Hess R. Schur E. Phillips RS. Rigotti N. Making the most of mentors: a guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84:140–144. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906e8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barondess JA. A brief history of mentoring. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1994;106:1–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Healy CC. Welchert AJ. Mentoring relations: A definition to advance research and practice. Educ Res. 1990;19:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mentoring Handbook. First. Dallas, TX: The American Heart Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLong TJ. Gabarro JJ. Lees RJ. Why mentoring matters in a hypercompetitive world. Harvard Business Rev. 2008:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bower DJ. Diehr S. Morzinski J. Simpson DE. Support-challenge-vision: A model for faculty mentoring. Med Teach Vol. 1998;20:595–597. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhagia J. Tinsley JA. The mentoring partnership. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:535–537. doi: 10.4065/75.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tobin MJ. Mentoring: Seven roles and some specifics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:114–117. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2405004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hitchcock MA. Bland CJ. Hekelman FP. Blumenthal MG. Professional networks: the influence of colleagues on the academic success of faculty. Acad Med. 1995;70:1108–1116. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199512000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer AP. Files JA. Ko MG. Blair JE. Academic advancement of women in medicine: Do socialized gender differences have a role in mentoring? Mayo Clin Proc. Feb. 2008;83:204–207. doi: 10.4065/83.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kram KE. Isabella LA. Mentoring alternatives: The role of peer relationships in career development. Acad Manage J. 1985;28:110–132. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill SEK. Bahniuk MH. Dobbs J. Mentoring and other communication support in the academic setting. Group Organ Stud. 1989;14:355–368. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pololi L. Knight S. Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:866–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.05007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayer AP. Files JA. Ko MG. Blair JE. The academic quilting bee. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:427–429. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0905-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Files JA. Blair JE. Mayer AP. Ko MG. Facilitated peer mentorship: A pilot program for academic advancement of female medical faculty. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:1009–1015. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins MC. Kram KE. Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: A developmental network perspective. Acad Manage Rev. 2001;26:264–288. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turban DB. Dougherty TW. Role of protege personality in receipt of mentoring and career success. Acad Manage J. 1994;37:688–702. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Detsky AS. Baerlocher MO. Academic mentoring—How to give it and how to get it. JAMA. 2007;297:2134–136. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.19.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morzinski JA. Simpson DE. Bower DJ. Diehr S. Faculty development through formal mentoring. Acad Med. 1994;69:267–269. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorndyke LE. Gusic ME. Milner RJ. Functional mentoring: A practical approach with multilevel outcomes. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28:157–164. doi: 10.1002/chp.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morzinski JA. Fisher JC. A nationwide study of the influence of faculty development programs on colleague relationships. Acad Med. 2002;77:402–406. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morzinski JA. Simpson DE. Outcomes of a comprehensive faculty development program for local, full-time faculty. Fam Med. 2003;35:434–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Connor MP. Bynoe AG. Redfern N. Pokora J. Clarke J. Developing senior doctors as mentors: A form of continuing professional development. Report Of an initiative to develop a network of senior doctors as mentors: 1994–1999. Med Educ. 2000;34:747–753. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]