Abstract

Context: Public policy regarding family caregiving for disabled older adults is affected by their estimated number, their attributes, and the services provided. The available national surveys, however, do not have a uniform approach to ascertaining the number of family caregivers, so their estimated number varies widely.

Methods: This article looks at nationally representative, population-based surveys of family caregivers conducted between 1985 and 2010 to find methods pertinent to ascertaining the number of caregivers. The surveys’ design, definition of disability, and approach to identifying and defining caregivers of disabled adults aged sixty-five and older were identified, and cross-survey estimates were compared.

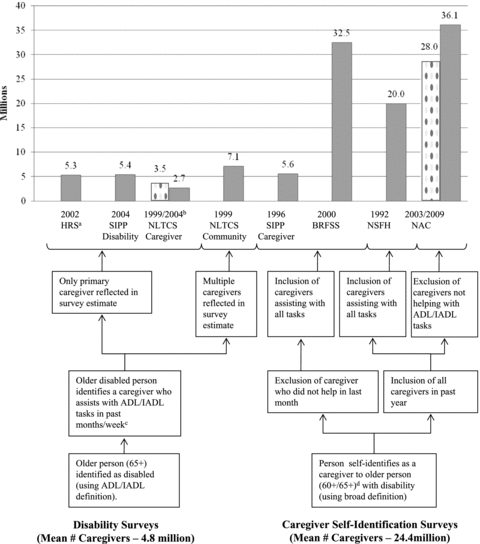

Findings: Published estimates of the numbers of caregivers of older disabled adults ranged from 2.7 million to 36.1 million in eight national surveys conducted between 1992 and 2009. The surveys were evenly divided between caregivers identified by disabled older adults (n= 4, “disability surveys”) and self-identified (n= 4, “caregiver self-identification surveys”). The estimated number of family caregivers of disabled adults aged sixty-five and older was, on average, 4.8 million in disability surveys and 24.4 million in caregiver self-identification surveys.

Conclusions: The number of family caregivers of disabled older adults estimated by national surveys varied substantially. Greater consistency in defining caregivers could yield more informative estimates and also advance policy efforts to more effectively monitor and support family caregivers.

Keywords: Caregiving, survey methodology, disability

The importance of family caregivers to disabled older adults’ health, health care, and long-term care service use has been well documented (Levine et al. 2010; Stone and Keigher 1994; Talley and Crews 2007). But in national surveys, the combination of ambiguity in defining what constitutes caregiving and the diverse methods of identifying a caregiver have contributed to wide variations in the estimated numbers of caregivers in the United States (Barer and Johnson 1990; Colello 2007; Gaugler, Kane, and Kane 2002; IOM 2008; Raveis, Siegel, and Sudit 1988; Stone 1991). Published national estimates of the number of informal caregivers of older disabled adults in this country range more than tenfold, from 2.7 million (Hong 2010) to 43.5 million (NAC and AARP 2009).

Government and advocacy reports also reflect this variation in estimates. For example, in 2000, the National Family Caregiver Support Program estimated that 7.7 million caregivers of older adults (aged 60+) fell within its potential target beneficiary pool (U.S. Administration on Aging 2002), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Healthy People 2010 cites an estimate of 32.5 million caregivers of older adults (aged 60+) (CDC 2006). The Administration on Aging states that there are 52 million caregivers of individuals of all ages and 7.1 million caregivers of older adults (aged 65+) (Takamura and Williams 1998). Literature from the AARP estimates that there are 43.5 million caregivers of older adults (aged 50+) (NAC and AARP 2009). Without a single national caregiver surveillance system, estimates have been drawn from a variety of national surveys of aging and caregiving (1996 Survey of Income and Program and Participation, 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, 1992 National Survey of Families and Households, 1989 National Long-Term Care Survey, and the 2009 National Alliance for Caregiving Survey). The national surveys’ methods of measurement likely explain some of the variation in estimates, but to our knowledge this variation has not yet been examined.

These different definitions and estimates have a significant bearing on the policy discussion in the United States about both support for informal caregivers and long-term care policy in general (Colello 2007; Rozario and Palley 2008; Spillman and Long 2009). As the number of older adults continues to grow and the number of potential caregivers continues to drop in this country (Spillman and Black 2005), a more centralized and comprehensive government caregiver support policy will become increasingly important (Vladeck 2004; IOM 2008; Talley and Crews 2007). In turn, the planning, budgeting, implementation, and evaluation of this policy will require a clear and accurate understanding of the size and composition of the caregiving population (Vladeck 2004; IOM 2008). To decide how the existing national surveys can best be used to shape such a policy, we first must understand how population-based survey design methods affect the estimated numbers of caregivers of disabled older adults.

Clear definitions and measurements are important to many areas of the social sciences. Recent studies have investigated inconsistencies in the measurement of disability among community-dwelling older adults and concluded that the definition of disability did indeed influence the estimates of prevalence (Freedman et al. 2004; Wiener et al. 1990; Wolf, Hunt, and Knickman 2005). We used a similar approach to examine conceptual issues regarding the definition of caregiving and to explore methodological variations across population-based surveys that measured caregiving. In this article, we build on the work of Gaugler, Kane, and Kane (2002) and Stone (1991) to explore the conceptualization of caregiving historically as well as its definition in current national surveys. We then examine national population-based surveys of caregiving of older disabled adults to find pertinent design attributes and methods, including definitions of caregiving and disability. Finally, we consider the implications of survey design for published estimates of the number of caregivers of older disabled adults.

Historical Conceptualization of Caregiving

Caregiving is a socially constructed term that first appeared in social science research during the second half of the twentieth century (Horowitz 1985; Tennstedt and McKinlay 1989). Several factors contributed to the initial growth of caregiving research in the 1970s. Increases in longevity and declines in fertility led to a greater proportion of the population living to old age. In 1965, the creation of the Medicare and Medicaid programs expanded government financing of health and long-term care. The inception of these programs—along with the decline in three-generational households, more older adults living independently, and more women having jobs outside of the household—led to concerns that working-age adults would no longer assume responsibility for older family members (Horowitz 1985; Marks 1996; Treas 1977).

Despite these worries, the research published in the 1970s and early 1980s indicated that families were continuing to provide most of the support for disabled older adults (Doty 1986; Shanas 1979; Treas 1977). In fact, as it became clear that families had assumed considerable responsibility for large numbers of older adults, the stresses associated with caregiving became a growing concern (Abel 1990; Cantor 1983; Raveis, Siegel, and Sudit 1988). Ways of reducing caregivers’ stress and prolonging their assistance were developed and are still being developed and evaluated (Sorensen, Pinquart, and Duberstein 2002; Tennstedt and McKinlay 1989).

These early studies of caregiving relied on convenience samples and were limited in generalizability, due in part to the difficulty of collecting information from frail and cognitively impaired older adults, who often were considered “too sick to participate” (Barer and Johnson 1990). The 1982 National Long Term Care Survey was the first national study that explored the health status, use of health care, and long-term needs of the oldest and frailest adults. In tandem with questions about older adults’ functional limitations, questions were asked about the assistance received and the people who provided it. The resulting caregiver supplement to the 1982 National Long Term Care Survey thus offered the first national profile of caregivers (Stone, Cafferata, and Sangl 1987). Since then, information regarding the provision of assistance to older adults has been collected in several national surveys. Despite the consensus that a “workforce” of caregivers is the predominant provider of care to older adults (IOM 2008), the surveys vary greatly in their methods of identifying caregivers as well as their definition of caregiving (Gaugler, Kane, and Kane 2002; Stone 1991). The extent to which the survey design and the definition of caregiving account for the variation in published estimates of the number of caregivers of disabled older adults has not, to our knowledge, yet been studied.

Conceptualization of Caregiving

In this article, we broadly define a caregiver as an individual who assists a family member or friend aged sixty-five or older who needs help with daily tasks because of a long-term illness or memory problem. This definition, however, leads to several questions about how caregiving is defined in policy, practice, and survey research. Drawing on the work of Stone (1991) and Gaugler, Kane and Kane (2002), we consider several methodological issues that are relevant to identifying caregivers for survey research purposes.

Identifying Key Informants

The need for assistance owing to “a long-term illness or memory problem” separates caregiving from the normative exchange of assistance across a lifetime. But this definition still leaves open the question of who (caregiver or care recipient) is better able to assess whether assistance is necessary. Despite the dyadic nature of caregiving, very few studies rely on responses obtained from both the caregiver and the care recipient. Instead, most national surveys elicit information about caregiving from either the care recipient (in “disability surveys”) or the caregiver (in caregiver “self-identification surveys”).

Most national disability surveys initially ask older adults a series of questions regarding their difficulty with various functional tasks. If the respondents or proxies report difficulty, they then are asked if they receive help with that functional task and from whom. Therefore, to be identified as a caregiver in these surveys, a person must be helping with a task with which the disabled older adult or proxy reports difficulty.

Conversely, caregiver self-identification surveys typically ask potential caregivers to self-identify whether they help an older disabled adult with daily tasks, sometimes specifying that this help is necessary because the older adult has a health or memory problem. This approach to identifying caregivers is dependent on caregivers’ perceptions of disability as well as whether and which tasks are specified as representative of a disability. Caregivers who self-identify in caregiver surveys may report providing assistance with tasks for which the older adult would not report having difficulty.

To our knowledge, only the National Long Term Care Survey collects information from both the caregiver and the care recipient. This survey first identifies disabled older adults, who then identify their informal caregivers. The primary informal caregiver is then surveyed separately as part of the Informal Caregiver Supplement. Although this survey looks at assistance from both members of the dyad, the care recipient's report of disability and assistance is still required to identify a caregiver, which therefore excludes those caregivers who provide assistance to older adults who do not report difficulty but who may be disabled.

Determining Functional Limitations

The variation in the definition of disability in national disability surveys has been well documented (Freedman et al. 2004). Although most surveys of disability ask about activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), the specific ADL/IADL tasks that are assessed, the wording of the questions, and the reference period over which the disability is assessed are not the same (Katz et al. 1963, 1970; Wiener et al. 1990).

The reference period over which disability is assessed is important because many surveys exclude those disabilities that are temporary or caused by stressful events. To eliminate short-term disabilities, surveys commonly ask respondents to report only those disabilities that have been present for a specific reference period, which differs in each survey. Furthermore, the exact onset of disability may be difficult to pinpoint if it is not due to a stressful event (such as stroke or heart failure). In fact, most caregivers tend to report a later date for the onset of a disability than clinically defined (Albert, Moss, and Lawton 1996; Seltzer and Li 1996).

Determining Caregiving Tasks

Although ADL/IADL tasks also are commonly used to define caregiving assistance, the specific activities, as well as the wording of the questions, are far from uniform or consistent in practice (Freedman et al. 2004; Wiener et al. 1990). Moreover, some caregivers may be providing assistance that is not characterized by traditional ADL/IADL tasks, such as offering emotional support, providing transportation, and arranging and monitoring health care (Bookman and Harrington 2007; Gaugler, Kane, and Kane 2002; Stone 1991; Stone and Keigher 1994). A recent review of how the caregiving experience has been defined suggests that caregiving usually involves two types of care: direct care provision and care management. Direct care may include skilled nursing care, support or supervision with tasks made difficult because of cognitive deficits, and hands-on care with ADL tasks. Care management may include in-home management activities such as hiring and supervising home care aides or out-of-home management activities such as arranging medical care, transportation, and financial management (Albert 2004). Although this framework may better describe caregivers’ multidomain experience, it is broad and may cover some tasks that reflect normative family exchanges, such as picking up groceries for a parent and making dinner for a spouse.

Sampling Frame of Care Recipients

Many disability surveys exclude from their sampling frame those individuals who reside in institutional settings, such as nursing homes, which therefore also omits the caregivers of individuals living in such settings. The distinction between community and facility, however, may be difficult to differentiate in long-term care settings such as senior housing, assisted living, and continuing-care communities (Harrington et al. 2005; Kane 1995). Furthermore, caregivers may continue to provide instrumental and emotional support after the care recipient has moved into a facility (Stone and Clements 2009). Another sampling frame consideration is the age of the care recipient who qualifies as an “older” adult. Surveys have various age cutoff points for collecting information from care recipients aged fifty and older, sixty and older, sixty-five and older, and beyond.

Secondary Caregivers

Most of the earlier studies focused on the provision of care by just one person, the primary caregiver (Cantro 1979, 1983; Shanas 1979); however, this approach fails to measure the assistance provided by a broader network (siblings, neighbors, relatives by marriage, etc.) (Soldo, Wolf, and Agree 1990). What little research does exist regarding secondary caregivers suggests that they may experience many of the same effects from caregiving (e.g., depression, physical health problems, financial problems) as primary caregivers do (Gaugler et al. 2003). Restricting the definition of caregiving to “primary” caregivers therefore may underestimate both the care provided to disabled older adults and its societal consequences.

Reimbursement

Most surveys distinguish between informal caregiving and formal caregiving based on whether a caregiver is reimbursed for the assistance provided (e.g., an informal caregiver is not paid and a formal caregiver is paid; see Allen and Ciambrone 2003; Litwak 1985). While this method clearly differentiates between a hired home care worker or a personal assistant and a family caregiver, this distinction becomes less clear when family and friends are paid to provide care and also continue to provide unpaid or “informal” care (Allen and Ciambrone 2003). For example, studies of the Cash and Counseling demonstration project in Arkansas, Florida, and New Jersey found that personal assistants hired through the Medicaid program (mostly sons and daughters of the Medicaid recipient) were paid for just half the hours of care they provided (Foster, Dale, and Brown 2007). Although most surveys would classify this caregiver as “paid,” most surveys do not necessarily regard this care as “formal.” Currently, the number of caregivers who fall into this category is small, although the Community Living Assistance Services and Support (CLASS) legislation recently passed as part of the health care reform bill will give qualifying disabled adults a daily allowance that can be used to pay family members for the care provided, thereby theoretically increasing the potential numbers of informal caregivers paid for only part of their care (Span 2010).

Methods of Systematically Reviewing National Surveys of Caregiving

The conceptual and methodological issues reviewed in the preceding sections highlight the multiple dimensions of surveys of caregivers. To understand how these criteria may influence published estimates, we conducted a comprehensive literature and database review to identify and examine population-based national surveys that collect information on caregiving and the published estimates of caregiving based on those surveys.

Survey Identification

We identified the relevant surveys through three sources: the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Directory Data Resources database (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2009), the National Library of Medicine Health Services and Sciences Research Resources database (National Information Center on Health Services Research and Health Care Technology 2009), and PubMed (National Library of Medicine 2009). To be included in the review, the surveys had to meet the following criteria:

Rely on an observational survey design.

Employ a probability sampling design.

Include individuals providing task assistance to older adults (65+) with a physical or cognitive disability.

Generate nationally representative estimates (through weighting techniques).

Have been conducted within the past twenty-five years (1985–2010).

Fifteen national surveys met these criteria. We then conducted a comprehensive literature review using scientific journal databases, policy-report search engines, and general-interest Internet search engines to determine whether the survey had been analyzed to estimate the weighted number of caregivers of older adults or the number of older adults receiving informal support (for more about our literature search methodology, see the appendix). This review resulted in nine surveys, eight of which contained publicly available documentation regarding the study design. The following eight surveys were included in this synthesis:

The National Long Term Care Community Survey (NLTCS-Community): 1999

The National Long Term Care Informal Caregiver Supplement (NLTCS-CG): 1999/2004

Health and Retirement Survey (HRS): 2002

Survey of Income and Program Participation Caregiver Module (SIPP-CG): 1996

Survey of Income and Program Participation Disability Module (SIPP-Disability): 2004

National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH): 1992

National Alliance for Caregiving/AARP Caregiving in the US Survey (NAC): 2003/2009

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS): 2000

The NLTCS asked disabled care recipients in the community survey (NLTCS-Community) about caregiving and asked for more detailed information from the person they identified as their primary caregiver (2004) or the person providing the most hours of care (1999) in the Informal Caregiver Supplement (NLTCS-CG). Each survey (NLTCS-Community and NLTCS-CG) was examined separately. In addition, two surveys contained published estimates from several waves within the time span of the selected surveys (1992–2009): the NLTCS-CG estimates from 1999 and 2004 and the NAC estimates from 2003 and 2009. To allow for greater temporal comparability, we included in our study estimates from both time periods. The NAC's design did not change between the two waves of data collection. The NLTCS used a different method to identify the primary caregiver for the NLTCS-CG in 2004, compared with the NLTCS-CG in 1999 (primary caregiver identified by care recipient as “person who helps the most” versus primary caregiver identified as person providing the most hours of care, respectively).

Survey Characteristics

Information about the caregiver identification protocol, survey design, and definition of caregiving was taken from each survey to look for explanations of variation in caregiving estimates. Those aspects of the caregiver identification protocol that we examined were (1) who identified the caregiver, (2) who was interviewed (caregiver or care recipient), (3) the population from which the care recipient was drawn, and (4) the population from which the caregiver was drawn. The survey design elements were (1) the survey design (cross-sectional or longitudinal), (2) the survey mode, (3) the sampling frame, and (4) the sampling units. The criteria used to define caregiving for each survey were (1) the types of assistance provided, (2) the reason for needing assistance, (3) the number of supplemental caregivers identified (if any), and (4) the reference period. Since several of the surveys predicated caregiving on disability, we also examined the definition of disability. The criteria for a disability were (1) specific ADL/IADL tasks used to define the disability, (2) whether the disability was due to a health problem or condition, and (3) the reference period for the disability.

Estimates of Caregiving

We read peer-reviewed literature and government reports from the past twenty-five years (1985–2010) to find published national estimates of the number of caregivers of adults aged sixty-five and older. We could not obtain two estimates of caregivers exclusively providing assistance for individuals sixty-five and older. The BRFSS estimate covered all caregivers of adults aged sixty (not 65+) and older, and the SIPP-CG estimate included all caregivers of a parent, spouse, neighbor, or other relative, thereby excluding caregivers of a child or sibling (for a more detailed description of caregiving estimates, see figure 1). Note that the estimates of caregiving were taken from published secondary analyses of databases and are therefore contingent on the individual authors’ construction of the caregiving variable and weighting scheme.

Figure 1.

Estimated Number of Caregivers of Older Adults in the United States from National Surveys.

Notes: Published weighted estimates of the number of caregivers of older adults in the United States ranged from 2.7 million to 36.1 million. Several factors in the survey design were associated with variation in the estimates. Surveys in which caregivers self-identified resulted in larger published estimates (mean estimate of 24.4 million) than did surveys in which caregivers were identified by a disabled individual (mean estimate of 4.8 million caregivers). aSources of weighted estimates: (1) 2002 HRS: inferred from the number of adults 65+ reporting receiving help with ADL and IADL tasks ( Johnson and Wiener 2006); (2) 2004 SIPP-Disability: inferred from estimated number of community residents aged 65+ receiving help with ADL/IADL tasks (Kaye, Harrington, and LaPlante 2010); (3) 1999 NLTCS-CG: estimated number of primary caregivers of adult 65+ obtained from the profile published by Wolff and Kasper (2006); (4) 2004 NLTCS-CG: estimated number of caregivers of adults aged 65+ reported in study by Hong (2010); (5) 1999 NLTCS-Community: estimated number of caregivers of adults 65+ drawn from the National Family Caregiver Support Program Resource Guide (U.S. Administration on Aging 2002); (6) SIPP-Caregiver: estimate of caregivers obtained from profile published in the National Family Caregiver Support Program Resource Guide; however the report did not specify what proportion of the 9.4 million caregivers provided assistance solely to older adults. Therefore, the estimate of 5.6 million is the number of caregivers who self-identified as caring for a parent (1.5 million), spouse (1.4 million), neighbor (750,000), or other relative (2 million) and excludes individuals caring for a child (2.4 million) or cases in which the relationship was not identified (1.4 million). This estimate is therefore likely an overestimate, as it includes caregivers of younger adults (Alecxih, Zeruld, and Olearczyk 2001); (7) NSFH: estimate was reported as 11% of the adult population in 1990 (184.8 million community-dwelling adults in 1990, according to U.S. Census data) caring for an adult 65+ (Marks 1996); (8) 2003 NAC: calculated from the published report of 63% of the total caregiving population (reported as 44.4 million) caring for an adult 65+ (NAC and AARP 2004); (9) 2009 NAC: calculated from the published report of 83% of the total care of someone 50+ (reported as 43.5 million) caring for an adult aged 65+ (NAC and AARP 2009); (10) BRFSS: reported as 15.56% of the adult population in 2000 (209.1 million community-dwelling adults in 2000, according to U.S. Census data) providing care for an adult 60+ (CDC 2000). bThe 2004 NLTCS-CG survey analysis (Hong 2010) used a different weighting scheme from the 1999 NLTCS-CG survey analysis (Wolff and Kasper 2006); therefore, the estimates are not comparable over time. cHelp was assessed over four months in SIPP-Disability, past week in NLTCS-Community and NLTCS-CG, and not specified in the HRS. dWhen possible, estimates were restricted to caregivers of adults aged 65 and older; however, in the BRFSS and the SIPP-CG, this was not possible.

Results

Caregiver Identification Protocol

We divided the surveys into two broad groups based on their approach to identifying caregivers (see table 1). Four surveys (HRS, NLTCS-CG, NLTCS-Community, and SIPP-Disability) first identified disabled individuals using ADL/IADL criteria and then asked them to name the person who helped them with daily tasks (if anyone did help them). In all but one of these “disability” surveys (NLTCS-CG), the disabled person or proxy was the respondent and provided information about the caregiver. In all but one of the disability surveys (HRS), the care recipients were restricted to community-dwelling adults.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Eight Selected National Surveys of Caregivers to Older Adults

| Disability Surveysa |

Caregiver Self-Identification Surveysb |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRS 2002 | NLTCS-CG 1999/2004 | NLTCS-Community 1999 | SIPP-Disability 2004 | SIPP-CG 1996 | NSFH 1992 | NAC 2003/2009 | BRFSS 2000 | ||

| Caregiver Identification Protocol | Who identifies caregiver? | Disabled person or proxy | Disabled person or proxy | Disabled person or proxy | Disabled person or proxy | Caregiver | Caregiver | Caregiver | Caregiver |

| Who is interviewed? | Disabled person or proxy | Caregiver | Disabled person or proxy | Disabled person or proxy | Caregiver or proxy | Caregiver or proxy | Caregiver | Caregiver | |

| Population from which CR is drawn | Persons aged 50+ and spouses | Community-dwelling persons aged 65+ | Community-dwelling persons aged 65+ | Community-dwelling persons aged 15+ | Persons aged 15+ | Undefined | Persons aged 18+ | Persons aged 60+ | |

| Population from which CG is drawn | Persons identified by disabled HRS respondents | Primary caregivers identified by disabled NLTCS respondents | Persons identified by disabled NLTCS respondents | Persons identified by disabled SIPP respondents | Community-dwelling persons aged 15+ | Community-dwelling persons aged 19+ | Community-dwelling persons aged 18+ | Community-dwelling persons aged 18+ | |

| Survey Design Elements | Survey design and mode | Telephone panel survey | In-person panel survey | In-person panel survey | Telephone panel survey | Telephone panel survey | Telephone panel survey | Telephone cross-sectional survey | Telephone cross-sectional survey |

| Sample frame | Dual frame: (1) households (2) Medicare enrollment | NLTCS | Medicare enrollment files | U.S. Census | U.S. Census | Households | RDD | U.S. Census | |

| Sample units | Individuals and couples | Individuals | Individuals | Individuals | Individuals | Individuals | Individuals | Households | |

Notes: HRS = Health and Retirement Survey; NLTCS-CG = National Long Term Care Informal Caregiver Supplement; NLTCS-Community = National Long Term Care Community Survey; SIPP-Disability = Survey of Income and Program Participation Disability Module; SIPP-CG = Survey of Income and Program Participation Caregiver Module; NSFH = National Survey of Families and Households; NAC = National Alliance for Caregiving/Caregiving in America Survey; BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CR = Care-recipient; CG = Caregiver; RDD = Random digit dialing.

“Disability surveys” refers to surveys in which caregivers are identified by disabled persons within a defined sampling frame.

“Caregiver self-identification surveys” refers to surveys in which individuals from the general population identified themselves as a caregiver of an older disabled person.

Four surveys (SIPP-CG, NSFH, NAC, and BRFSS) asked individuals in the general population whether they identified themselves as a caregiver and then collected information directly from the caregiver. These “caregiver self-identification surveys” also asked individuals in the general community if they provided care to an adult because of an illness, disability, or old age, regardless of the care recipients’ location of residence. Thus, the SIPP-CG, NSFH, BRFSS, and NAC samples did not exclude caregivers to individuals in long-stay nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and a range of other congregate settings.

Survey Design Elements

The eight surveys varied in mode and design (see table 1). All but two surveys (NLTCS-CG and NLTCS-Community) were conducted by telephone, and most were panel surveys, with the exception of the NAC and BRFSS. (The HRS's initial interview was conducted in person, and all follow-up interviews were conducted over the phone.) Three surveys (HRS, NLTCS-CG, and NLTCS-Community) were limited to older adults but differed in the age of adults in their sampling frame. The HRS sampled adults aged fifty and older and their spouses, whereas the NLTCS was restricted to individuals aged sixty-five and older. The remaining surveys used the U.S. Census and household listings for the sampling frame and sampled caregivers of care recipients across a broader age span. The BRFSS was restricted to caregivers of individuals aged sixty and older; the NAC sampled caregivers of individuals eighteen and older; and the SIPP-CG sampled caregivers of individuals aged fifteen and older. All the surveys except for the BRFSS used the individual as the sample unit. Likewise, the age range of the caregivers varied slightly across the surveys. Whereas most restricted caregivers to individuals aged eighteen and older, the SIPP-CG and SIPP-Disability included caregivers aged fifteen and older. (Note that although these surveys included caregivers of a younger disabled population, the estimated numbers of caregivers presented in this article are restricted to disabled older adults.)

Definition of Disability

The criteria used to define disability were disaggregated for each survey to find potential sources of variability. These criteria included the definition of disability (ADL/IADL or another definition), specific ADL and IADL tasks, whether disability was defined as contingent on a health problem, and the reference period over which disability was assessed (see table 2). All four disability surveys (HRS, NLTCS-CG, NLTCS-Community, and SIPP-Disability) used ADL and IADL limitations to ascertain the care recipients’ disability, although each imposed a different set of ADL and IADL task criteria. Similarly, the ADL and IADL limitations were contingent on being due to a physical or mental health problem. To restrict the sample to “chronically” disabled adults, the NLTCS-Community, NLTCS-CG, and HRS defined a disability as a limitation that had lasted at least three months (or was expected to last three months), whereas the SIPP-Disability was less explicit and simply instructed the respondent to “exclude temporary conditions.”

TABLE 2.

Definition of Disability Used to Ascertain Care Recipients’ Disability in Eight Selected National Surveys of Caregivers of Older Adults

| Disability Surveys |

Caregiver Self-Identification Surveys |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRS 2002 | NLTCS-CG 1999/2004 | NLTCS-Community 1999 | SIPP-Disability 2004 | SIPP-CG 1996 | NSFH 1992 | NAC 2003/2009 | BRFSS 2000 | ||

| Definition of Disability | ADL/IADL | ADL/IADL | ADL/IADL | ADL/IADL | Any; no parameters | Any condition or illness | Any; no parameters | Elderly, long-term illness or disability | |

| ADL Tasks Assessed | Dressing | X | X | X | X | ADL disability in CR not assessed | ADL disability in CR not assessed | ADL disability in CR not assesseda | ADL disability in CR not assessed |

| Bathing/Shower | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Eating | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Transferring between bed and chair | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Using the toilet | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Walking | X | ||||||||

| Walking across a room | X | ||||||||

| Getting around inside | X | X | X | ||||||

| IADL Tasks Assessed | Preparing meals | X | X | X | X | IADL disability in CR not assessed | IADL disability in CR not assessed | IADL disability in CR not assesseda | IADL disability in CR not assessed |

| Shopping | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Getting around outside | X | X | X | ||||||

| Using the phone | X | X | X | ||||||

| Managing medications | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Managing money | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Doing light housework | X | X | X | ||||||

| Doing heavy housework | X | X | |||||||

| Doing laundry | X | X | |||||||

| Reason for Disability | “Because of a memory or physical health problem” | None for ADL; disability or health problem for IADL | None for ADL; disability or health problem for IADL | “Because of a disability” | Any; not specified | Due to a health or disability problem | Any; not specified | Any; not specified | |

| Reference Period for Disability | Present at least three months | Present at least three months | Present at least three months | “Exclude effects of temporary conditions” | “Long-term” | Not specified | Anytime over past twelve months | “Long-term” | |

Notes:

Although the NAC did not assess ADL/IADL disability in the CR, caregivers were identified as providing ADL/IADL assistance “as a result of [the CR's] condition.” The ADL/IADL tasks asked of caregivers included dressing, bathing or showering, eating, transferring between bed and chair, using the toilet, dealing with diapers or incontinence, preparing meals, shopping, using transportation, managing medications, managing money, doing housework, and arranging or supervising services.

HRS = Health and Retirement Survey; NLTCS-CG = National Long Term Care Informal Caregiver Supplement; NLTCS-Community = National Long Term Care Community Survey; SIPP-Disability = Survey of Income and Program Participation Disability Module; SIPP-CG = Survey of Income and Program Participation Caregiver Module; NSFH = National Survey of Families and Households; NAC = National Alliance for Caregiving/Caregiving in America Survey; BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CR = Care-recipient

The caregiver self-identification surveys (SIPP-CG, NSFH, NAC, and BRFSS) were less specific in defining disability. They did not rely on a specific set of ADL or IADL limitations, and the ascertainment of disability was left to the respondent (e.g., “Do you assist someone because of a long-term illness or disability?”). In all but one caregiver self-identification survey (NSFH), the disability was not restricted to limitations due to health. None of the four surveys imposed a reference period over which the disability was assessed. The caregivers were individuals who had provided care over the past year (NAC) or “on a long-term basis” (SIPP-CG and BRFSS), regardless of whether they were actively providing care at the time of the survey and without regard to the chronicity of the care recipient's disability.

Definition of Caregiving

We examined each survey's definition of caregiving in regard to five criteria (see table 3). In all four disability surveys, caregiving was contingent on the provision of ADL and IADL tasks, and three of the surveys further imposed a reference period over which the caregiving assistance was assessed. In the NLTCS-Community and NLTCS-CG, caregivers were included in the sample only if they had provided help within the past week. Although the HRS did not provide a specific reference period over which the caregiving was assessed, the reference period for a disability (a limitation that had been present for three months or would be present for at least three months) implied that the caregivers were currently providing care. The same logic could be applied to the SIPP-Disability, which had a four-month reference period but also assessed caregiving only for current disabilities.

TABLE 3.

Criteria Used to Define Caregiving in Eight Selected National Surveys of Caregivers of Older Adults

| Disability Surveys |

Caregiver Self-Identification Surveys |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRS 2002 | NLTCS-CG 1999/2004 | NLTCS-Community 1999/2004 | SIPP-Disability 2004 | SIPP-CG 1996 | NSFH 1992 | NAC 2003/2009 | BRFSS 2000 | |

| Assistance Provided | ADL/IADL | ADL/IADL | ADL/IADL | ADL/IADL | Not specified | Not specified | ADL/IADLa | Not specified |

| Reason for Assistance | Because of disability | Because of disability | Because of disability | Not specified | Because of illness or disability | Because of disability | 2003: “to help them take care of themselves” 2009: “as a result of their condition” | Not specified |

| Reference Period for Assistance | Not specified | Past week | Past week | 4 months | Care on a regular basis during past month | Anytime over past 12 months | Anytime over past 12 months | Care on a regular basis during past month |

| Paid CG Included | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Not specified | No | Yes |

| Number of Helpers per CR | 7 ADL 6 IADL 2 Finance | 20 | 1 | 2 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

Notes:

The ADL/IADL tasks asked of caregivers included dressing, bathing or showering, eating, transferring between bed and chair, using the toilet, dealing with diapers or incontinence, preparing meals, shopping, using transportation, managing medications, managing money, doing housework, and arranging or supervising services.

HRS = Health and Retirement Survey; NLTCS-CG = National Long Term Care Informal Caregiver Supplement; NLTCS-Community = National Long Term Care Community Module; SIPP-Disability = Survey of Income and Program Participation Disability Module; SIPP-CG = Survey of Income and Program Participation Caregiver Module; NSFH = National Survey of Families and Households; NAC = National Alliance for Caregiving/Caregiving in America Survey; BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CR = Care-recipient; CG = Caregiver; ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

One criterion that varied significantly across disability surveys was the number of caregivers per care recipient. For efficiency, surveys may restrict the numbers of individuals listed as helpers, but here the maximum number of potential caregivers differed. The NLTCS-Community collected information for as many as twenty helpers per disabled individual but included only the primary caregiver in the Informal Caregiver Supplement. The HRS collected information for as many as fifteen helpers. A final issue pertains to the inclusion of paid caregivers: with the exception of the NLTCS-CG, the disability surveys included paid caregivers.

Caregiver self-identification surveys typically did not specify the kinds of assistance provided; only the NAC excluded caregivers who did not help with ADL and IADL tasks. Except for the BRFSS, caregiver self-identification surveys defined caregiving as “provided because of a disability.” The reference period over which the caregiving was measured varied substantially across the caregiver self-identification surveys. The NSFH and NAC included any care provided in the past year, whereas the SIPP-CG and BRFSS included only care provided in the past month. Note that although the NAC 2009 included all caregivers in its study sample, it also asked about the care currently being provided. Only the BRFSS included paid caregivers.

Published Estimates of Caregiving

Finally, published estimates of the numbers of caregivers of disabled older adults were depicted in relation to the major survey design criteria (see figure 1). These published estimates varied from 2.7 million

(2004 NLTCS-CG) to 36.1 million caregivers of disabled older adults (2009 NAC), with a mean of 14.6 million. The estimates of caregivers that were derived from the four disability surveys (HRS, NLTCS-CG 1999 and 2004, NLTCS-Community, and SIPP-Disability) ranged from 2.7 million (2004 NLTCS-CG) to 7.1 million (1999 NLTCS-Community), with a mean of 4.8 million. The estimates of caregivers that were derived from caregiver self-identification surveys (SIPP-CG, NSFH, NAC 2003 and 2009, and BRFSS) ranged from 5.6 million (SIPP-CG) to 36.1 million (2009 NAC), with a mean of 24.4 million.

We might further differentiate the disability surveys between the estimates restricted to primary caregivers (5.3 million in 2002 HRS, 2.7 million in 2004 NLTCS, 3.5 million in 1999 NLTCS-CG, 5.4 million in 2004 SIPP-Disability) and the estimate that included multiple caregivers for each care recipient (7.1 million in the 1999 NLTCS-Community). Additional differences are evident in those surveys that did not specify a reference period for caregiving (5.3 million in 2002 HRS) or had a longer reference period of four months (5.4 million in SIPP-Disability) and in the NLTCS-CG, which specified the provision of assistance during the previous week (2.7 million in 2004 NLTCS, 3.5 million in 1999 NLTCS-CG; not shown in figure 1; to see table 3 for more details).

The caregiver self-identification surveys may be further differentiated by the reference period over which caregiving was assessed. The NSFH (20.0 million) and the NAC (28.0 million in 2003; 36.1 million in 2009) covered all individuals who provided care over the past year, whereas the SIPP-CG (5.6 million) and the BRFSS (32.5 million) tracked only that care provided in the past month. In addition, the NAC excluded caregivers who did not assist with ADL/IADL tasks, whereas the SIPP-CG, NSFH, and BRFSS included caregivers assisting with all types of tasks.

The estimates for the two surveys with published data available from more recent waves (NLTCS-CG and NAC) should be interpreted with caution. Both surveys used a different weighting scheme across the two time points, so we cannot compare the estimates over time. Also, a slight change in the process for identifying primary caregivers between 1999 and 2004 in the NLTCS-CG could affect the profiles of the primary caregivers selected for the Informal Caregiver Survey (but not the overall number of caregivers identified as primary caregivers).

Discussion

The results of our study establish the tremendous variability in the national surveys’ estimated numbers of caregivers of disabled older adults. Although family and friend caregivers are the principal providers of care to disabled older adults in the community (IOM 2008; Levine et al. 2010), we found a lack of consensus regarding the definition and scope of the caregiver role. The ambiguity of what a caregiver is no doubt contributed to the wide range of approaches to the national surveys’ definitions of caregivers and their measurements. The fact that the numbers of caregivers of disabled adults approximately sixty-five years of age and older that were estimated from population-based national surveys ranged from 2.7 million to 36.1 million—more than a tenfold difference—underscores the need for greater conceptual clarity and measurement precision.

Our study demonstrates that how caregivers are identified and how disabilities are defined in order to identify care recipients profoundly affect the estimated numbers of caregivers and, by extension, the national policies intended to improve their experiences and well-being. Surveys that identify caregivers by means of a well-defined reference population of disabled individuals (“disability surveys”) uniformly use a more specific approach to measuring older adults’ disability and to defining caregivers, and they yield an average estimate of 4.8 million (ranging from 2.7 million to 7.1 million) family caregivers of disabled older adults. Conversely, surveys that ask caregivers to self-identify from the general population (“caregiver self-identification surveys”) define disabilities in less specificity and thus yield a much higher average of 24.4 million (ranging from 5.6 million to 36.1 million) family caregivers of disabled older adults.

Several discrepancies between disability surveys and caregiver self-identification surveys could explain the threefold difference in mean estimates. The exclusion of disabled individuals living in institutions, such as long-stay nursing homes, from disability surveys’ sampling frames would logically lead to estimates smaller than those of caregiver self-identification surveys, which do not exclude them. However, the number of older adults living in long-stay nursing homes (estimated by the 2000 census at 1.56 million) is far smaller than the observed differences between disability surveys and caregiver self-identification surveys (U.S. Census Bureau 2007). Studies of disability ascertainment indicate that disabled older adults self-report lower rates of impairment in ADL/IADL tasks than do their proxy respondents, which, by extension, would suggest that disability surveys also would produce lower disability prevalence estimates and numbers of caregivers, as observed (Magaziner et al. 1988, 1997). Although contrary to our findings, one theory of caregiver self-identification posits that while caregivers might report more disabilities in care recipients, they may not identify themselves as caregivers until well into their caregiving experience (Kutner 2001; O’Connor 2007). Given the broad definition of disability used in caregiver self-identification surveys, we cannot comment definitively on why observed estimates vary by so much across these groups of surveys.

Beyond the caregiver identification protocol, several other survey design considerations influenced the estimation of caregivers. The variation among disability surveys (HRS, NLTCS-CG, NLTCS-Community, and SIPP-Disability) in their estimated numbers of caregivers is largely attributed to their exclusion of secondary caregivers (the estimates of NLTCS-CG, HRS, and SIPP-Disability are only of primary caregivers) and the length of the reference period over which caregiving was assessed.

The variation among caregiver self-identification surveys (SIPP-CG, NSFH, BRFSS, and NAC) in the numbers of estimated caregivers is less clearly attributable to individual survey design elements. The reference period (which varied from one month to one year), the inclusion of paid caregivers, and the types of assistance provided did not systematically correspond to the size of the estimates. Although we would expect the estimates of caregiving over the past year to be larger than the estimates over the past month, we did not find this to be true in the BRFSS, which estimated 32.5 million caregivers in the past month. The BRFSS's possible inclusion of caregivers of nondisabled older adults (the BRFSS includes any care provided to someone who is “elderly or has a long-term illness or disability”[italics added]) and the use of a broader age range of individuals aged sixty and older likely contributed to the larger estimate.

The one-month reference period probably also partly explains why the SIPP-CG's estimate (5.6 million) is much lower than the NAC's estimate (36.1 million) and the NSFH's estimate (20.0 million), but it does not explain why the SIPP-CG's estimate is so much lower than the BRFSS's estimate (32.5 million). While there is no way to determine why the SIPP's estimate was so low, we suggest two possible explanations. First, the SIPP-CG's estimate could be an underestimate, because of the way in which the number was derived. Because the SIPP-CG did not collect information about the age of the care recipient, this estimated number reflects the proportion of 9.4 million individuals that the SIPP-CG identified as caregivers who were caring for a parent, spouse, or nonrelative. In addition, the SIPP-CG restricted its sample to individuals caring for someone because of a “long-term illness or disability” (as opposed to someone “elderly or with a long-term illness,” as in the BRFSS).

The NAC, which restricted its caregiving estimate to individuals providing ADL or IADL assistance, yielded the largest estimate, as compared with other surveys that did not restrict the sample to individuals providing ADL or IADL assistance (BRFSS, SIPP-CG, and NSFH). The difference between this estimate (36.1 million) and the mean for caregiver self-identification surveys (24.4 million) suggests that either the NAC's estimate contains some individuals providing normative assistance to family members or other surveys are not identifying a significant proportion of caregivers of disabled family members. It is useful to consider this estimate of 36.1 million caregivers assisting an adult aged sixty-five and older in relation to the broader population demographics. Given that approximately 15 million older adults have some difficulty with hearing, vision, cognition, ambulation, self-care, or independent living (U.S. Administration on Aging 2009b), this estimate might mean that on average, each disabled older adult receives help from two or more caregivers. Stated differently, if the NAC's estimate reflects the number of caregivers of any older adult aged sixty-five or older (estimated to be 39 million), nine out of every ten older adults could have a caregiver.

We should note the several limitations of our study. First, although the contributing surveys were spread over seventeen years (1992 to 2009), an examination of temporal trends in the surveys’ estimates was beyond the scope of our study. To allow for the most meaningful comparison, we selected survey waves as close in time as possible. By presenting the most recent published data available (e.g., NLTCS 2004 and NAC 2009), our intent was to examine estimates from surveys with the greatest comparability and to acknowledge the more recent data that are available. The design and definition of caregiving have remained constant for surveys that have collected additional waves of data in the past five years (HRS 2008, SIPP-Disability 2008, SIPP-CG 2008). Therefore, although more recent estimates from these sources were not available, the methodological issues that we discuss here can be applied to estimates from more recent waves. Even though estimates of caregiving from before 2000 may not seem relevant to policy discussions in 2010, these surveys are still being used by both researchers and policy advocates to estimate the cost and impact of caregiving (AARP 2008; U.S. Senate 2005; Wiener 2009). For example, the NAC and AARP's recent report on the economic value of caregiving uses several sources to estimate the number of caregivers, some from as far back as 1986 (AARP 2008; Arno, Levine, and Memmott 1999).

A second limitation of our study is that we derived our estimates from previously published secondary analyses of databases and were therefore limited by the published reports’ description of methods of how caregiving was carried out and weights constructed. Although infrequently reported in detail, the weighting scheme may have a dramatic impact on survey estimates. For example, the difference between the 2003 and 2009 NAC estimates (more than 8 million) is large and may be attributed almost entirely to the change in the weighting scheme between those years. Most telling is that the NAC's analysis of trends between 2003 and 2009 indicates no significant increase in the number of caregivers when the weighting scheme from 2003 was applied to the 2009 data (for a more detailed description of weights, see NAC and AARP 2009). The same effect, although in the reverse direction, can be seen for the NLTCS-CG. The lack of detailed information regarding weights makes it difficult not only to compare estimates across surveys but also to make comparisons over time (Hong 2010; Wolff and Kasper 2006).

It is important to make clear how much the survey design has influenced our understanding of caregiving in ways that extend beyond numbers of caregivers. This may be most important to understanding vulnerable or less-studied subgroups of caregivers, such as very young or very old caregivers and caregivers with limited resources (Levine et al. 2005). A study of these vulnerable subgroups is limited, however, by the data available. For example, several of the surveys in our review excluded caregivers under age eighteen, even though some evidence suggests that more and more children are acting as caregivers of grandparents and other relatives (Levine et al. 2005).

New surveys of aging and caregiving will be challenged to adjust to the growing diversity in older adults’ living arrangements, family dynamics, and ambiguity in paid care arrangements. Over the past century, families have become more geographically dispersed, and older adults are living independently for longer periods of time (Doty 1986; Treas 1977; Wolf, Hunt, and Knickman 2005). As a result, the number of “long-distance” caregivers who coordinate and supervise services for parents or siblings living in different states is believed to have increased (Collins et al. 2003; MetLife 2004). The type of assistance provided by long-distance caregivers, such as coordination of services and communication with the care recipient's health care team, have typically been excluded from standard ADL/IADL tasks (Albert 2004; MetLife 2004). (Although the NAC includes the coordination and supervision of services as an IADL task in its survey, this task is not one of the original IADL tasks proposed by Katz and colleagues.) In addition, policy changes such as growth in Home and Community Based Waiver (HCBW) programs have increased the number of family and friend caregivers who are paid for a portion of the care they provide (Kaiser 2009). Whether these family caregivers who provide both paid and unpaid care should be considered part of the “formal caregiving workforce” or “informal family caregivers” is not clear but may have important implications for future estimates of the number of informal caregivers.

Policy Implications

The lack of a common conceptual definition of caregiving is perhaps understandable given the competing interests of advocacy groups and policymakers. Advocacy groups are interested in raising awareness of the magnitude of the issue and in lobbying for additional resources, support programs, or research by demonstrating that many people offer care to others of all ages. Conversely, policymakers may hesitate to develop policies that support such a large number of informal caregivers, for fear that caregivers will replace their “free” informal care with “publicly funded” formal care as more public care and support options become available. Likewise, the lack of consensus regarding the size and composition of the caregiving population most in need of support has contributed to those government caregiver support policies that have been described as fragmented, underfunded, and difficult to evaluate (Feinberg and Newman 2006; Rozario and Palley 2008; Staicovici 2003).

Of the current government policies that offer some support to caregivers (Lifespan Respite Care Act, National Family Caregiver Support Program [NFCSP], Medicaid Home and Community Based Services [HCBS] waiver programs, the Family and Medical Leave Act, various tax credits, and, starting in 2012, the Community Living Assistance Service and Support [CLASS] Act), only the NFCSP is designed to directly benefit caregivers. The NFCSP is a block-grant program that was established in 2001 with an annual budget of around $155 million. The NFCSP defines caregiving broadly as assistance provided to someone aged sixty or older with a physical or mental limitation, and increasing the funding for this program has been a priority for caregiver advocacy organizations in recent years (AARP 2008; Feinberg and Newman 2006). As the estimated number of caregivers eligible for the benefit affects its relative generosity, relying on a broad definition of caregiving and a large population with diverse needs creates several implementation and resource constraints. For example, the FY 2009 budget for this program nationally was $154 million (U.S. Administration on Aging 2009a), which works out to a benefit of approximately $4.50 for each caregiver, using the NAC's estimate of 36.1 million caregivers. Even if the budget were doubled, the benefit would remain meager.

One of policymakers’ long-standing interests regarding long-term care (LTC) is preventing or deferring entry into a nursing home by providing access to community-based services, including the support of informal caregivers. During the last decade, the funding for Home and Community Based Service waivers within the Medicaid program has been increased, and recently, the CLASS Act was passed (Kaiser 2009). Both programs are structured to give functionally disabled adults some form of cash allowance or reimbursement to spend on supportive services, such as adult day care, a home health aide, respite care for caregivers, or payment to informal caregivers for some of their care. Under the CLASS Act, participating individuals with two to three ADL limitations who are vested in the program will receive an allowance of no less than $50 a day ($18,250 a year), which could be used to pay a family caregiver (Span 2010). The potential benefit of such programs for caregivers is financially greater than that of the NFCSP, depending on the care recipient's eligibility and enrollment in the program.

Although it is important to recognize the diversity of caregiving arrangements and experiences, from a fiscal point of view a caregiver policy would benefit from objective and defensible criteria for determining who most needs assistance and might benefit most from supportive services (Vladeck 2004). One way of establishing these criteria is to frame caregivers’ concerns in the context of larger policy issues such as Medicaid LTC costs or health insurance (Rozario and Palley 2008; Staicovici 2003). For example, supporting informal caregivers who are at risk of “burnout” has been embraced as one way to prevent or delay disabled adults living in the community from entering a nursing home, thereby reducing LTC costs (Spillman and Long 2009). Another group relevant to policymaking is employed caregivers who might have to drop out of the workforce to care for a family member, often resulting in the loss of health insurance for both the caregivers and their families (Ho et al. 2005). These policy concerns could help determine future changes in existing surveys and the development of new surveys. Any changes in measurement should take into account what types of caregivers are most vulnerable to strain at home or in the workplace related to providing care, as well as what services or supports are most effective in reducing caregiver-related stress (Spillman and Long 2009; Vladeck 2004).

As our review has demonstrated, the definition and identification of caregivers and the design of national surveys greatly influence the resulting estimates. Because demographic trends and advances in medical technology will produce more and more older adults requiring long-term care in the coming years, transparency and explicit data about who is providing care and to whom are now more important than ever before. The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), funded by the National Institute on Aging (successor to the NLTCS), will move us closer, we hope, to this goal by interviewing both older adults and their caregivers, thereby giving us a better understanding of caregiving, care recipients’ disabilities, and caregivers’ resources, attributes, and needs (Agree 2010). Given the considerable expense of institutional care, the widespread preference of older adults to age in place, and the pervasive support and common practice for families to care for one another, finding a comprehensive and consistent approach to monitoring and supporting older disabled adults and their families will emerge as a high priority for policy in the coming years.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by dissertation research grants from the Jacob and Valeria Langeloth Foundation, the National Institute on Aging, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of Travonia Hughes, Judith D. Kasper, Chad Boult, Emily Agree, and Qian-Li Xue, all at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health.

Appendix

National Surveys Containing Information on Caregiving

| Survey Name: Sponsor | Years | Information about Caregiving | Inclusion in or Exclusion from Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS): Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) | 1997 | The 1997 MEPS Household Component supplemental public-use files collected information from individuals of all ages in MEPS with certain limitations on (1) care provided by other household members and (2) individuals outside the household who could provide care. | Excluded: Never used to generate estimate of caregiving | |

| Medicare Current Beneficiaries Survey (MCBS): Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) | 1991–current | The MCBS's health status and functioning section contains basic information about those persons who helped the primary respondent (Medicare beneficiary) with ADLs, IADLs, Medicare insurance decisions, and/or Medicare paperwork. Information is collected about these tasks and the helper's relationship to the respondent. | Excluded: Never used to generate estimate of caregiving | |

| Longitudinal Study on Aging (LSOA): National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and National Institute of Aging (NIA) | Cohort identified in 1984 | The original SOA (Study on Aging) supplement to the NHIS collected information on a cohort of individuals aged 55+. The supplement contains information about individuals who helped the respondent, basic information about the amount and type of assistance provided, and the respondent's satisfaction with the care provided. A follow-up was conducted in 1990. | Excluded: Survey cohort identified before 1985 | |

| Health and Retirement Survey/Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (HRS): National Institute on Aging (NIA) | 1992–Current | The HRS's functional limitations section collects information from the entire cohort of older HRS respondents (65+) on ADL and IADL limitations and the individuals who assist with these limitations. Basic information is collected on the relationship of the helper and the respondent, as well as the type and amount of assistance provided. | Included | |

| National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS): National Institute on | Community | 1982–2004 | The NLTCS collects information on chronically disabled older adults in the U.S. The community sample includes individuals 65+ who have been disabled (ADL or IADL limitation) for at least three months. | Included |

| Aging (NIA) | Informal Caregiver Supplement | 1982–2004 | This is a supplemental survey for the NLTCS community survey. The primary caregiver identified in the community survey was interviewed and detailed information about the caregiver and caregiving situation was collected. | Included |

| National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and National Institute of Aging (NIA) | Cohort identified in 1988 | This longitudinal survey follows an original cohort of families from the first wave of the study in 1988 and their descendants in two subsequent waves, the most recent in 2001/2002. Each wave asked respondents about personal care they provide and receive from individuals both inside and outside the household. The survey collects basic information about the amount and type of care provided and received. | Included | |

| Caregiving in the U.S.: AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) | 1997, 2003 | This cross-sectional, national telephone survey of households in the U.S. collects information about care provided by household members for a health problem in other individuals of any age. The survey collects detailed information about the caregiver and the impact of caregiving. | Included | |

| Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey (BRFSS): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | 2000 | The BRFSS is an annual cross-sectional national survey of households in the U.S. In 2000, two questions were added to the survey about caregiving to individuals over the age of 60. Individual states have the option to supplement these two questions with more in-depth questions about caregiving. | Included | |

| Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP): U.S. Census Bureau | Adult Disability Module | 1996, 2001, 2004 | The SIPP is a cross-sectional survey of U.S. households and collects information about income and participation in government programs. The Adult Disability Module collects information about functional limitations and assistance provided by family and friends. Basic information is collected on the relationship of the helper and the respondent, as well as the type of assistance provided. | Included |

| Informal Caregiving Module | 1996, 2001, 2004 | This SIPP module asks individuals in the general community about the assistance they provide to disabled adults inside and outside the home, as well as basic information about the amount and type of care provided in households. | Included | |

| Survey of Long-Term Care from the Caregivers Perspective: Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), Harvard University, and others | 1998 | This small national telephone survey collected information on caregiving of individuals of any age, as well as detailed information about the type and amount of care provided and its burdens and rewards. | Excluded owing to lack of information about survey design | |

| American Time Use Survey (ATUS): U.S. Department of Labor | 2003–2006 | The ATUS measures the amount of time people spend on various activities, including “helping activities.” Respondents use time diaries to record how much time they spend caring for both adults and children in the household, including providing physical care or obtaining medical services for older adults living in the household. | Excluded: Never used to generate estimate of caregiving | |

| Panel Study of Income Dynamics: National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Commerce, National Institute on Aging | 1991, 1993 | The PSID collects information about families and income. The Parent Health Supplement collects information from adult children caring for parents 70+ who need assistance with personal tasks. The Health Care Burden Supplement collects information from families on the health status of older adults and the impact (primarily financial) on their families. | Excluded: Never used to generate estimate of caregiving | |

| National Survey of Self-Care and Aging: National Institute on Aging | 1993 | This survey of older individuals (65+) collected information about self-care behaviors regarding activities of daily living and chronic condition management. Although the focus is on self-care, the amount and type of assistance provided by others also are recorded. In addition, this survey asks about the amount and type of care provided by older adults to other individuals. | Excluded: Never used to generate estimate of caregiving | |

Note: For the literature review, we used scientific journal databases, focused on medical and social science (PubMed, Social Science Citation Index, and PsychInfo). The searches used the terms caregiver, caregiving, or informal care in combination with the name of the survey. We then reviewed the results of the search to determine whether the study generated an estimate of caregiving of older adults. To identify those government reports that used data from the selected surveys, we used the U.S. DHHS's Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation website and the National Family Caregiver Support Program website. We used the same search terms to find articles and reports and then again to find more articles and reports.

References

- AARP Public Policy Institute. Valuing the Invaluable: The Economic Value of Family Caregiving, 2008 update. 2008. Available at: http://www.aarp.org/relationships/caregiving/info-11-2008/i13_caregiving.htmlaccessed July 7, 2010. [PubMed]

- Abel EK. Informal Care for Disabled Elderly: A Critique of Recent Literature. Research on Aging. 1990;12:139–57. doi: 10.1177/0164027590122001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agree E. Personal communication. Baltimore: National Health and Aging Trends Study, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Albert SM. Beyond ADL-IADL: Recognizing the Full Scope of Family Caregiving. In: Levine C, editor. Family Caregivers on the Job: Moving beyond ADLs and IADLs. New York: United Hospital Fund; 2004. pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Albert SM, Moss M, Lawton MP. The Significance of the Self-Perceived Start of Caregiving. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 1996;2:161. [Google Scholar]

- Alecxih L, Zeruld S, Olearczyk B. Characteristics of Caregivers Based on the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Washington, DC: Lewin Group; 2001. Available at: http://www.lewin.com/content/publications/1557.pdfaccessed July 1, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allen SM, Ciambrone D. Community Care for People with Disability: Blurring Boundaries between Formal and Informal Caregivers. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:207–26. doi: 10.1177/1049732302239599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arno PS, Levine C, Memmott MM. The Economic Value of Informal Caregiving. Health Affairs. 1999;18:182–88. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barer BM, Johnson CL. A Critique of the Caregiving Literature. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:26. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookman A, Harrington M. Family Caregivers: A Shadow Workforce in the Geriatric Health Care System? Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2007;23:1105–41. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2007-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor MH. Neighbors and Friends: An Overlooked Resource in the Informal Support System. Research on Aging. 1979;1:434–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor MH. Strain among Caregivers: A Study of Experience in the United States. The Gerontologist. 1983;23:597–604. doi: 10.1093/geront/23.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Codebook. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/technical_infodata/surveydata/2000.htm#surveyaccessed May 5, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Healthy People 2010 Midcourse Review. 2006. Disability and Secondary Conditions. ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/Data/midcourse/html/focusareas/FA06ProgressHP.htmaccessed May 5, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Colello KJ. Family Caregiving to the Older Population: Background, Federal Programs and Issues for Congress. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Services Report for Congress; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WL, Holt TA, Moore SE, Bledsoe LK. Long-Distance Caregiving: A Case Study of an African-American Family. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2003;18:309–16. doi: 10.1177/153331750301800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty P. Family Care of the Elderly: The Role of Public Policy. The Milbank Quarterly. 1986;64:34–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF, Newman SL. Preliminary Experiences of the States in Implementing the National Family Caregiver Support Program: A 50-State Study. Journal of Aging and Social Policy. 2006;18:95–113. doi: 10.1300/J031v18n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster L, Dale SB, Brown R. How Caregivers and Workers Fared in Cash and Counseling. Health Services Research. 2007;42:510–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Crimmins E, Schoeni RF, Spillman BC, Aykan H, Kramarow E, Land K, et al. Resolving Inconsistencies in Trends in Old-Age Disability: Report from a Technical Working Group. Demography. 2004;41:417–41. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA. Family Care for Older Adults with Disabilities: Toward More Targeted and Interpretable Research. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2002;54:205–31. doi: 10.2190/FACK-QE61-Y2J8-5L68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Mendiondo M, Smith CD, Schmitt FA. Secondary Dementia Caregiving and Its Consequences. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2003;18:300–308. doi: 10.1177/153331750301800505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington C, Chapman S, Miller E, Miller N, Newcomer R. Trends in the Supply of Long-Term-Care Facilities and Beds in the United States. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2005;24:265–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ho A, Collins SR, Davis K, Doty MM. A Look at Working-Age Caregivers’ Roles, Health Concerns, and Need for Support. Washington, DC: Commonwealth Fund; 2005. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Issue-Briefs/2005/Aug/A-Look-at-Working-Age-Caregivers-Roles--Health-Concerns--and-Need-for-Support.aspxaccessed May 1, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. Understanding Patterns of Service Utilization among Informal Caregivers of Community Older Adults. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(1):87–99. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A. Family Caregiving to the Frail Elderly. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 1985;5:194–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) Retooling for an Aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RW, Wiener JM. A Profile of Frail Older Americans and Their Caregivers. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2006. Available at: http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/311284_older_americans.pdfaccessed July 28, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid Home and Community-Based Service Programs: Data Update. 2009. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/7720.cfmaccessed May 1, 2010.

- Kane RA. Expanding the Home Care Concept: Blurring Distinctions among Home Care, Institutional Care, and Other Long-Term-Care Services. The Milbank Quarterly. 1995;73:161–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in Development of the Index of ADL. The Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of ADL: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–19. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye HS, Harrington C, LaPlante MP. Long-Term Care: Who Gets It, Who Provides It, Who Pays, and How Much? Health Affairs. 2010;29:11–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner G. AARP Caregiver Identification Study. Washington, DC: AARP; 2001. Available at: http://www.familycaregiving101.org/not_alone/AARPSurveyFinal.pdfaccessed July 28, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Levine C, Halper D, Peist A, Gould DA. Bridging Troubled Waters: Family Caregivers, Transitions, and Long-Term Care. Health Affairs. 2010;29:116–24. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine C, Hunt GG, Halper D, Hart AY, Lautz J, Gould DA. Young Adult Caregivers: A First Look at an Unstudied Population. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(11):2071–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E. Helping the Elderly: The Complementary Roles of Informal Networks and Formal Systems. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, Hebel JR. Patient-Proxy Response Comparability on Measures of Patient Health and Functional Status. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1988;41(11):1065–74. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaziner J, Zimmerman SI, Gruber-Baldini AL, Hebel JR, Fox KM. Proxy Reporting in Five Areas of Functional Status. Comparison with Self-Reports and Observations of Performance. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146(5):418–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks N. Caregiving across the Lifespan: National Prevalence and Predictors. Family Relations: Journal of Applied Family and Child Studies. 1996;45:27–36. [Google Scholar]