Abstract

An important function of the endothelium is to regulate the transport of liquid and solutes across the semi-permeable vascular endothelial barrier. Two cellular pathways have been identified controlling endothelial barrier function. The normally restrictive paracellular pathway, which can become “leaky” during inflammation when gaps are induced between endothelial cells at the level of adherens and tight junctional complexes, and the transcellular pathway, which transports plasma proteins the size of albumin via transcytosis in vesicle carriers originating from cell surface caveolae. During non-inflammatory conditions, caveolae-mediated transport may be the primary mechanism of vascular permeability regulation of fluid phase molecules as well as lipids, hormones, and peptides that bind avidly to albumin. Src family protein tyrosine kinases have been implicated in the upstream signaling pathways that lead to endothelial hyperpermeability through both the paracellular and transcellular pathways. Endothelial barrier dysfunction not only affects vascular homeostasis and cell metabolism, but also governs drug delivery to underlying cells and tissues. In this review of the field, we discuss the current understanding of Src signaling in regulating paracellular and transcellular endothelial permeability pathways and effects on endogenous macromolecule and drug delivery.

Keywords: Src tyrosine kinases, endothelium, vascular permeability, inflammation, drug delivery, caveolae

1. Introduction

The vascular endothelium lining the blood vessels functions as a barrier between the blood and interstitial compartments that controls and restricts the transendothelial flux of fluid and macromolecules [1]. Increased endothelial permeability to plasma proteins resulting from endothelial barrier dysfunction leads to an abnormal extravasation of blood components and accumulation of fluid in the extravascular space. Vascular leakage not only causes multi-organ dysfunction, but also compromises the normal pharmacokinetics of therapeutic drugs. In such areas with increased vascular permeability, drugs can extravasate and accumulate inside the interstitial space. The bioavailability and effectiveness is therefore reduced and systemic toxicity can increase. Strategies which prevent vascular leakage therefore reduce drug dosages and side effects, and improve the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

The pathological process of endothelial hyperpermeability is a common characteristic feature of many diseases, including inflammation, trauma, sepsis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, diabetes, and atherosclerosis. The homeostatic barrier function of the endothelium is ultimately maintained by the dynamic regulation of endothelial cell shape, endothelial cell-cell adherence, and endothelial-extracellular matrix adherence [2]. Compromised barrier function of the endothelium in response to proinflammatory mediators is accompanied by intercellular gap formation, which is the main mechanism of vascular leakage. Recently, evidence has emerged to support a role for the vesicular pathway in mediating macromolecular transport across the endothelium [1]. In particular, protein transport via caveolae has been reported to play a key role in maintaining endothelial barrier function and normal oncotic pressure gradient across the vessel wall [1,2].

Multiple signaling molecules have been identified in the mechanism of vascular endothelial permeability regulation [1] which trigger structural changes in endothelial barrier and/or induce transcellular protein transport by endothelial cells. Src protein tyrosine kinases regulate many cellular processes, such as cell morphology, motility, proliferation, and survival. Intracellular signal transduction via Src protein tyrosine kinases is also involved in acute inflammatory responses [1]. Recent experimental evidence points to the importance of Src family protein tyrosine kinases (SFK) signaling in the regulation of microvascular barrier function and various endothelial responses including hyperpermeability to different proinflammatory mediators [3-6]. Src family protein tyrosine kinases have been implicated in upstream signaling pathways that lead to endothelial hyperpermeability through both intercellular gap formation and increased transendothelial protein transport [1]. Elevated SFK activaty results in changes in gene expression which also affects endothelial permeability [7]. Over the last decade, some exhaustive and basic reviews addressing the regulation of endothelial permeability have been published [1]. However, a comprehensive review on the role of SFK signaling in modulation of endothelial barrier is still lacking. This review addresses the potential mechanisms of Src protein tyrosine kinases in regulating endothelial permeability and microvascular barrier function.

2. Basics of Src family tyrosine kinases

SFKs are nonreceptor, cytoplasmic, protein tyrosine kinases. They have been implicated in the regulation of diverse processes including cell growth and differentiation, cell adhesion and motility, carcinogenesis, immune cell function, and endothelial permeability. This broad-spectrum role of SFKs in regulating biological responses is associated with their ability to interact with a large number of different receptors and many distinct cellular targets [8]. The structural and functional interaction between SFKs and cellular receptors integrates a large amount of upstream signaling that coordinately regulates cellular activities.

2.1 The structure of SFKs

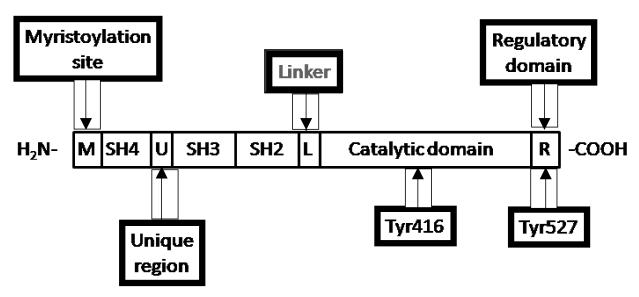

The SFKs are 52-62 kDa enzymes composed of eight distinct functional regions (Figure 1). From the N- to C-terminus, these regions include a myristylated site, Src homology (SH)4 domain, unique region, SH3 domain, SH2 domain, linker, the kinase/catalytic domain (SH1 domain), and regulatory domain. The glycine at position 2 is important for addition of a myristic acid moiety, and the myristoylated site along with the SH4 domain are associated with cell membrane binding. The unique region is specific for different Src family members and it may mediate the interaction between SFKs and other proteins. The three major domains, the kinase/catalytic domain (SH1 domain), SH2 domain, and SH3 domain, represent the modular structure of Src family kinases. SH3 and SH2 domains are protein-protein interaction domains shared not only with other Src family kinases but also with many other signaling proteins. The SH2 domain binds phosphotyrosine motifs in either an inter- or intramolecular fashion. The SH1 domain is the site of tyrosine kinase activity. There are two major phosphorylation sites on Src: on Tyr 416 located in the SH1 domain and at Tyr 527 in the regulatory domain near the carboxyl terminus. Tyr 416 can be auto-phosphorylated, whereas Tyr 527 can be phosphorylated and dephosphorylated by various proteins, such as Csk (carboxy-terminal Src kinase) which phosphorylates Src, and SHP-1 (Src-homology 2 domain containing phosphatase 1), SHP-2, or PTP1 (protein tyrosine phosphatase 1) which dephosphorylate Src (8,12). Both phosphorylation sites play a key role in regulating the activity of Src family kinases [7].

Figure 1. Src family kinase domain structure.

Chicken (c)-Src is shown.

2.2 Activation of Src family kinases

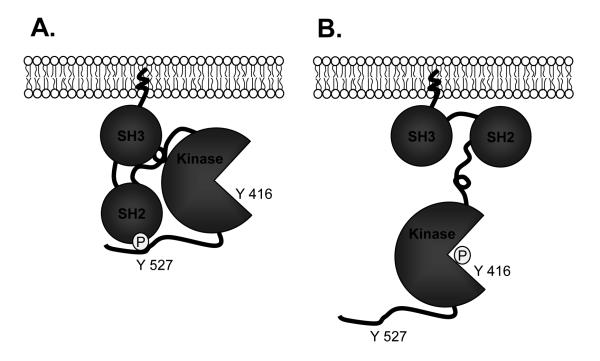

SFKs are phosphorylated on tyrosine residues, suggesting that Src activity and biological function might be regulated by phosphorylation. The inactive state of the Src kinases is maintained by an autoinhibitory interaction between the SH2 domain and Tyr527 (chicken c- Src) and also the interaction of the SH3 domain and a polyproline type II helix in the SH2 to SH1 linker domain (7). SFKs can switch from an inactive to an active state through control of its phosphorylation state, or through protein-protein interactions. They are activated by phosphorylation at Tyr 416 and dephosphorylation at Tyr 527 [9-11]. In contrast, the activity of SFKs is decreased by dephosphorylation at Tyr416 and phosphorylation at Tyr 527 (Figure 2). Under physiological conditions, 90–95% of c-Src is phosphorylated at Tyr 527 [12], and phosphotyrosine 527 binds intramolecularly with the SH2 domain [13], indicating that SFKs have low basal activity. This inhibitory interaction can also be displaced by a phosphotyrosine ligand with a higher affinity for the SH2 domain (7).

Figure 2. Activation of c-Src.

Panel (A) represents the inactive state of Src, when Src assumes a “closed” conformation stabilized by the interaction between Tyr527 and the SH2 domain, and SH3 domain-linker-catalytic domain interaction. Panel (B) represents the the “open” or active state of Src. Adapted from REF. 7.

Protein interactions also act to regulate Src by either directly activating them, or by moving SFKs to sites of action. SFKs can be activated by receptor protein-tyrosine kinases, integrin receptors, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), antigen- and Fc-coupled receptors, cytokine receptors, and steroid hormone receptors [10]. Many proinflammatory cytokines activate SFKs via different GPCR signaling pathways that include Gi- and Gq-coupled receptors. Stimulation of Gi-coupled receptor is known to activate Src in a Gβγ-dependent manner [14].

2.3 Expression and substrates of Src family kinases in endothelial cells

There are nine members of the Src family including c- Src, Fyn, Yes, Yrk, Lyn, Lck, Hck, Fgr and Blk (Table 1). c-Src, Fyn, Yes and Yrk are widely coexpressed in many cell types, including vascular endothelial cells [9,15,16], whereas Lyn, Lck, Hck, Fgr and Blk are found primarily in hematopoietic cells [8]. SFKs localize to numerous areas of the cell rather than in any one particular subcellular location. It appears that the subcellular location of SFKs can affect their function. SFKs can associate with cellular membranes, such as the plasma membrane, the perinuclear membrane, and the endosomal membrane. SFKs are also found in the cytoplasm and at adherens junctions, where they take on different roles. The function of SFKs in endothelial cells is complicated by the pleiotropic activities, as well as their targeting molecules. A variety of SFK target molecules (substrates) are related to the regulation of endothelial permeability (Table 2).

Table 1.

Expression of Src family kinases

| Src family kinases | Expression |

|---|---|

| Src | Ubiquitous |

| Fyn | Ubiquitous |

| Yes | Ubiquitous |

| Yrk | Ubiquitous, only in chickens |

| Lyn | Myeloid cells, B-cells, Brain |

| Hck | Myeloid cells |

| Fgr | Myeloid cells, B-cells |

| Blk | B-cells |

| Lck | T-cells, NK cells, brain |

Table 2.

Src family kinase target proteins that regulate endothelial permeability

| Substrates | References |

|---|---|

| FAK | 17-19 |

| paxillin | 20 |

| vinculin | 21 |

| talin | 21 |

| ezrin/radixin/moesin | 22 |

| cortactin | 23,24 |

| catenins (β, γ and p120) | 25-31 |

| connexin 43 | 32 |

| caveolin-1 | 33-43 |

| PKCδ | 44 |

| PLC-γ | 45 |

| MLCK | 46 |

| PI-3K | 47 |

| SHP-2 | 48 |

| PP2A | 49 |

| p190RhoGAP | 50,51 |

| p120rasGAP | 51 |

Abbreviations: FAK, focal adhesion kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; PLC, Phospholipase C; MLCK, myosinlight chain kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; SHP-2, protein tyrosine phosphatase 2, PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A

3. Src family kinase signaling in vascular endothelial permeability

The route of solute flux across the vascular endothelium has been debated for decades. The transendothelial movement of solutes, ions and water can occur via both transcellular and paracellular pathways, through or between cells, respectively. The transcellular pathway consists of a highly mobile set of vesicles that shuttle across the endothelial barrier from its luminal aspect to the abluminal side [52]. The paracellular pathway, in contrast, offers a purely passive pathway for the diffusion of protein and other small solutes. Vascular permeability is determined primarily by multi-protein complexes, the tight and adherens junctions, that link adjacent endothelial cells. In absence of a pathological insult, these junctions are normally impermeable to albumin and other plasma proteins. Electron micrographic studies have shown that this pathway is closed (restricted) and excludes macromolecule tracers [53-57]. The transport of albumin and other macromolecules across the endothelium under non-inflammatory physiological conditions can be fully explained by transcytosis involving the plasma membrane vesicular structures or caveolae [54, 58].

SFKs have been implicated in upstream signaling pathways that lead to endothelial hyperpermeability [4,9,20]. The regulatory role of SFKs in endothelial permeability is two fold. SFK phosphorylation of proteins may directly modulate the function of these proteins. It phosphorylates substrates in the cytosol and at the inner face of the plasma membrane, or at cell–matrix or cell–cell adhesions. In addition, phosphotyrosyl residues serve as docking sites for the binding of signaling proteins containing SH2 domains. These signaling complexes initiate pathways that regulate protein synthesis, gene expression, cytoskeletal assembly, and many other aspects of cell function. Low levels of SFK activity is required in normal tissues to maintain integrity of the endothelial barrier. However, elevated Src activity induced by a wide spectrum of inflammatory mediators causes a marked increase in endothelial permeability [59-61].

3.1 Role of Src in paracellular permeability

3.1.1 Structural basis of paracellular permeability

The microvascular barrier consists of the endothelial monolayer, intercellular contacts between adjacent endothelial cells, and focal adhesions anchoring the endothelial lining to its surrounding matrices in the vascular wall. The integrity of these structural elements is necessary to maintain normal barrier function. The disintegration of endothelial cell-cell contact (junctions) and cell-matrix contact (focal adhesions) leads to increased endothelial permeability through the opening of paracellular pathways, enhancing macromolecular transport [62-68]. Paracellular permeability is regulated by interendothelial junctional complexes, the adherens junctions (AJ) and tight junctions (TJ), and through interaction of these complexes with the actin cytoskeleton [2].

Inter-endothelial cell contacts

Endothelial cells form junctional complexes consisting of TJs and AJs, which are the sites of diffusional transport of solutes. The integrity of interendothelial junctions can be impaired by endothelial cell retraction and shape change. Actin and myosin are the major contractile components in the cytoskeleton [63]. The signal transduction pathways that disrupt interendothelial junctions involve a complex series of signaling events leading ultimately to rapid and sustained phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC) and simultaneous inhibition of MLC-associated phosphatase (the function of which is to prevent dephosphorylation of MLC and prolong the contractile response) [46,69,70]. Phosphorylation of MLC by Ca2+-calmodulin dependent myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) is required for actin-myosin interaction and engagement of the endothelial contractile apparatus. Endothelial cell retraction is likely precipitated by disruption of endothelial AJs [46,71]. Filamentous actin within endothelial cells also associates with the cytoplasmic tail of the major AJ protein vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin [72]. Contractile force may “unhinge” AJs resulting in formation of gaps [71]. VE-cadherin is localized in intercellular AJs where they are linked in the cytoplasm to β-, γ-, and p120-catenins, and in turn to α-catenin and the actin cytoskeleton [25,26]. Dissociation of VE-cadherin from the catenins can cause intercellular gap formation leading to an increase in endothelial permeability [27,73].

Endothelial cell-matrix contacts

Focal adhesions are mainly composed of integrins, transmembrane receptors that facilitate the actin cytoskeleton connection to the extracellular matrix (ECM) via cytoplasmic linker proteins. The cell-matrix interaction is dynamically controlled through assembly and disassembly of focal adhesions [74]. The linkage between proteins of the ECM with the cell is mediated mainly by transmembrane integrins which not only function as adhesion receptors but also transmit chemical signals and mechanical forces between the matrix and cytoskeleton [75,76]. The adhesive interactions between integrins and their extracellular ligands at focal adhesion complexes regulate endothelial cell shape and serves to maintain endothelial barrier properties [2]. Integrin-mediated attachment of endothelial cells to the substratum is an important component of paracellular permeability. A recent study demonstrated that inhibition of integrin binding to either fibronectin or vitronectin with specific peptides containing the arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) sequence motif increased venular permeability 2- to 3-fold in a concentration-dependent manner [77].

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a protein tyrosine kinase which is recruited at an early stage to focal adhesions and which mediates many of the downstream signaling reactions leading to integrin engagement and focal adhesion assembly that ultimately affects barrier function [78-80]. The modulatory effect of FAK on endothelial permeability involves complex mechanisms depending on the chemical/physical states of the endothelium. In the basal condition, the constitutive activity of FAK is an essential component of the barrier structure. However, FAK can be further activated in response to inflammatory signals and stimulate paracellular transport of fluid and macromolecules through cell contraction and intercellular gap formation.

3.1.2 Src regulation in intercellular junctions

SFK-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation is considered to play an important role in regulating structural changes occurring in the endothelium [20,81]. The integrity of intercellular junctions can be regulated through phosphorylation of MLCK and AJ protein VE-cadherin by c-Src kinase [64,82-84]. Recent studies have identified sites of Src tyrosine phosphorylation in the unique N-terminus of endothelial MLCK-1. Phosporylation of MLCK-1 by Src results in a 2-3 fold increase in MLCK activity. MLCK activation is linked to increased MLCK tyrosine phosphorylation and stable association of MLCK with Src in pulmonary endothelial cells [9,23, 85]. Thus, Src binding to MLCK causes the activation of MLCK under submaximal calcium concentrations, providing a mechanism to orchestrate critical cytoskeletal rearrangements and cellular contraction [85]. Src regulates endothelial monolayer permeability at the cytoskeletal level by affecting myosin light chain phosphorylation [81]. These biochemical events induce actin-myosin contractility that leads to shape change of endothelial cells and interendothelial gap formation resulting in endothelial hyperpermeability. Alternatively, Src phosphorylation of both β-catenin and VE-cadherin can serve as important signaling mechanisms altering interactions between junctional and cytoskeletal proteins. Src tyrosine phosphorylation can also cause the dissociation of these junctional proteins from their cytoskeletal anchors [27,77,86,87]. Src kinase was found constitutively associated with VE-cadherin in both quiescent and angiogenic tissues [81]. VE-cadherin may serve as an anchor to maintain Src at endothelial cell junctions, where it could exert its activity on junctional components [81]. Src-VE-cadherin association in cultured endothelial cells is independent of VE-cadherin phosphorylation state and Src activation.

3.1.3 Src regulation at endothelial cell-matrix contacts

Both FAK and paxillin located in focal adhesion complexes are Src substrates. The activity of FAK and paxillin are mainly regulated through phosphorylation by the SFKs [10,17,84]. Association of c-Src with FAK may facilitate Src-mediated phosphorylation of tyrosine residues on FAK, some of which serve as binding sites for additional SH2-containing proteins [18,79]. Src is also involved in integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation [3]. Integrin engagement induces tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins found in focal adhesion complexes [4]. Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation is a critical requirement for the functional formation of integrin-dependent focal adhesion attachment to actin stress fibers [88]. Crosstalk between Src and focal adhesion kinase regulates vascular permeability by interfering with integrin adhesion and signaling [19,84].

3.2 Role of Src in transcellular permeability

3.2.1 Vesicle transport and transcellular permeability

Transport of the plasma protein albumin from the blood to underlying tissues is an important function of the endothelium. Under physiological conditions, the microvascular endothelium establishes a tight barrier (semipermeable cell-cell junctions) via AJs and TJs between neighboring cells. This keeps paracellular permeability of macromolecules, such as albumin, very low. Movement of these macromolecules does occur, however, through the vesicular or transcellular pathway involving caveolae. Recent data have shown convincingly that uptake and transport of albumin across the endothelial barrier in situ can be fully accounted for by the formation, fission and transport of caveolae [89-91].

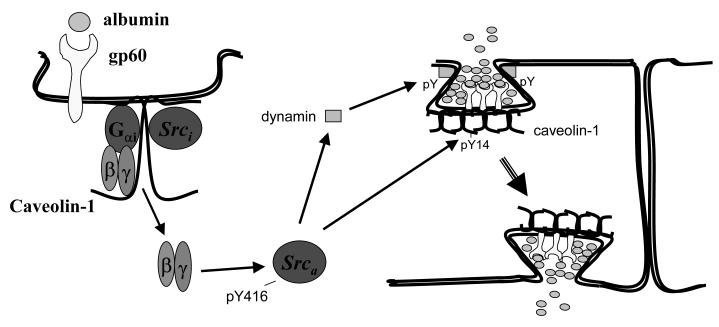

Transendothelial transport is rapid (~30 sec), the cargo is predominantly in the fluid phase rather than receptor-bound, and requires SFK signaling to activate vesicle shuttling between apical and basal surfaces [92]. Transcytosis can be regulated by albumin via both constitutive (eg, fluid phase transport) or receptor mediated processes (the molecule transported requires the presence of its cognate receptor in caveolae) [93]. Caveolin-1, an integral membrane protein (20-22 kDa), is a specific marker and the primary structural component of endothelial caveolae. Evidence has accumulated suggesting that caveolin-1 regulates endothelial transcellular transport of albumin. First, the recent generation of caveolin-1 null mice has revealed the absence of caveolae and defective uptake and transport of albumin, which could be reversed by transduction of caveolin-1 cDNA [33-35]. Furthermore, we [36-38] and others [39-43] have demonstrated that phosphorylation of caveolin-1 on tyrosine residue 14 by SFKs initiates plasmalemmal vesicle fission and transendothelial vesicular transport, and that this facilitates the uptake and transport of albumin through endothelial cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Src signaling mechanism regulating transcytosis of albumin.

Abbreviations: gp60, glycoprotein; Srci, inactive Src; Srca, active Src; pY, phosphorylated tyrosine.

3.2.2 Src regulation of transcellular permeability

The mechanism by which endothelial cells internalize and transport albumin from the luminal to abluminal side is not completely understood. Studies demonstrated that phosphorylation of caveolin-1 on tyrosine 14 by c-Src is a key switch initiating caveolar fission from the plasma membrane [36-41,43]. It is known that albumin binding to the 60 kDa glycoprotein (gp60) on the endothelial cell surface induces clustering of gp60 and its physical interaction with caveolin-1 [36]. c-Src can bind to the caveolin-1 scaffolding domain [41], palmitoylated C-terminal cysteine residue, and N-terminal phosphorylated tyrosine residue [36,41], and Src is activated upon albumin binding to cell surface gp60 [39]. Activated Src, in turn, phosphorylates caveolin-1, gp60, and dynamin-2 to initiate plasmalemmal vesicle fission and transendothelial vesicular transport of albumin (Figure 3) [37-39].

4. Role of Src signaling in proinflammatory mediator- and neutrophil-induced vascular hyperpermeability

4.1 Oxidants

Studies have shown that H2O2 increases the activity of c-Src and other SFKs, including Lck [94-96]. H2O2 directly activates Src via oxidization at two cysteine residues and indirectly through the dephosphorylation of Tyr 527 [97,98]. Exposure of endothelial cells to H2O2 increased Src activity in association with increased endothelial permeability [99]. Src kinase inhibitors, herbimycin A and PP1, prolonged the onset of increased permeability and attenuated H2O2-mediated increase in endothelial permeability [99]. However, Src family kinases do not appear to be involved in H2O2-mediated rearrangement of junctional proteins since H2O2-induced loss of VE-cadherin junctional staining along with concomitant gap formation was not affected by PP1 [100]. Although Src kinase activation has been shown to phosphorylate β-catenin and result in disorganization of the adherens junction complex [6,28,29], H2O2-induced decrease in the amount of β-catenin associated with the actin cytoskeleton was not blocked by PP1, suggesting that Src kinase activity is not involved in H2O2-mediated dissociation of β-catenin from the endothelial cell cytoskeleton. These findings raise the possibility that H2O2-mediated permeability stimulates both endothelial junctional disorganization and increased caveolae-mediated transcellular transport, and that inhibition of Src kinase ablates the vesicle trafficking-mediated permeability pathway [36].

4.2 TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) can induce increased endothelial permeability via intercellular gap formation [101]. A potential target for TNFα-induced endothelial permeability is VE-cadherin, a major component of endothelial AJs. TNFα activates Src kinases which results in tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin, redistribution of VE cadherin, and gap formation [27,87,102]. Confocal studies indicated that Src inhibitor PP2 prevented TNFα-induced phosphorylation of VE cadherin and intercellular gap formation, suggesting that a SFK activated by TNFα acts upstream of VE cadherin to affect changes in endothelial permeability [102]. The mechanism of Src activation stimulated by TNFα is unclear. It was suggested that TNFα-mediated oxidant generation in endothelial cells induces Src activation [103-106].

4.3 VEGF

Recent studies demonstrated that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced increased vascular permeability requires SFKs [107,108]. Mice lacking c-Src or Yes (but not Fyn) lacked a VEGF-mediated vascular permeability response [108]. The mechanism by which VEGF increases endothelial permeability through Src remains poorly understood. Unstimulated blood vessels contain a protein complex composed of VEGF receptor-1 (Flk-1), VE-cadherin, and β-catenin that is involved in maintenance of endothelial barrier integrity [31,39]. This molecular complex immediately dissociates following VEGF stimulation, an event that depends on Src kinase activity [109,110]. Src in its active form is recruited to Flk-1 following VEGF stimulation [111]. Therefore, it is conceivable that active Src associated with Flk-1 may account for the tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin and β-catenin, leading to dissociation of the junctional complex [112]. VEGF also promotes VE-cadherin endocytosis by regulating Vav2, a GEF, through c-Src [113]. VEGF stimulation results in the enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav2, together with Src and VEGF receptor-2, which was abolished by VEGF receptor-2 and SFK inhibitors. Src has an important function in linking VEGF receptor-2 activation to the stimulation of Vav2, thereby activating Rac and resulting in the endocytosis of VE-cadherin and the disruption of endothelial junctions. In addition, β-arrestin-2 may also aid VE-cadherin endocytosis based on its ability to interact with Src [114]. In this scenario, β-arrestin-2 may recruit Src to the vicinity of VE-cadherin, thus facilitating Src-dependent phosphorylation of cadherin–catenin complexes [110,115]. Therefore, the tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin and its associated molecules may be coordinated with the Src-dependent activation of Vav2 and Rac to regulate the dynamic disassembly and reassembly of adherens junctions. This process leads to the disassembly of endothelial-cell junctions, resulting in the enhanced permeability of the blood-vessel wall. In addition, Src kinase also regulates VEGF-induced assembly of a FAK/αvβ5 integrin complex in cultured endothelial cells. This complex was significantly reduced in endothelial cells from c-Src-deficient mice [2]. Pharmacological inhibition of SFKs with PP1 or retroviral delivery of kinase-defective c-Src suppressed VEGF-induced assembly of the FAK/αvβ5 complex. These findings indicate that the VEGF-induced formation of the FAK/αvβ5-complex via Src may be an important mechanism for coordinating growth factor-dependent integrin signaling in the regulation of vascular permeability [2, 116].

4.4 Thrombin

Thrombin, a pro-coagulant serine protease, is well known to increase vascular endothelial permeability [1]. Thrombin-induced Ca2+ influx is regulated by Src activation. Ca2+ signaling is critical in the mechanism of thrombin-induced myosin light chain phosphorylation and subsequent actinomyosin cross bridging (which induces actin stress fiber formation) [62, 65,71, 116-118]. The mechanism by which Src regulates Ca2+ influx is unclear. Src may phosphorylate plasma membrane transient receptor potential channels expressed in endothelial cells [119,120] that mediate Ca2+ influx during inositol trisphosphate-sensitive intracellular store depletion [121,122]. Thrombin increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of junctional proteins and the formation of interendothelial gaps that are characteristically associated with the loss of barrier function [2,11,66,67,123]. Tyrosine phosphorylation of adherens junction proteins is dependent on the augmented Ca2+ influx. These results suggest that the Src activation-dependent Ca2+ influx is an important factor signaling thrombin-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction [124]. Src is also involved in thrombin-mediated changes in endothelial cell adherens junctions. Thrombin treatment of human umbilical vein endothelial cells promotes Src-dependent SHP-2 phosphorylation and dissociation from VE-cadherin complexes. The loss of SHP-2 from the cadherin complex correlates with a dramatic increase in the tyrosine phosphorylation of β-, γ-, and p120-catenins complexed with VE-cadherin. Thrombin regulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin-associated β-catenin, γ-catenin, and p120-catenin by modulating the quantity of SHP-2 associated with VE-cadherin complexes. This event promotes cell-cell junction disassembly and intercellular gap formation, detected in endothelial cell monolayers after thrombin treatment, and the resulting increase in monolayer permeability [48].

4.5 Neutrophils

It is well known that activated polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) increase the permeability of the endothelium to albumin, thus promoting fluid loss into the interstitial space. Although the precise mechanisms have not been completely elucidated, studies have implicated an increase in paracellular permeability via opening of interendothelial junctions caused by PMN adherence and oxidant generation by PMNs and endothelial cells which leads to increased solute (mainly albumin) and fluid transport across the vessel wall [1,125,126]. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that Src activation is linked to the mechanism of increased endothelial permeability caused by PMNs [4,23,127]. Activation of PMNs with complement peptide C5a induced endothelial cell Src activation and increased endothelial permeability. This PMN-induced hyperpermeability in both microvessels and endothelial cells could be greatly attenuated by Src inhibition [127]. Moreover, cross-linking of endothelial cell surface intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 with a monoclonal antibody also increased the activity of Src kinase (128-131), suggesting that PMN adhesion via CD18/ICAM-1 interaction may be important in the regulation of Src activity. The mechanism by which activated PMNs increase Src activity is not clear. Activation of PMNs may increase Src Tyr416 phosphorylation and reduce Src Tyr527 phosphorylation [127]. Src and β-catenin interaction and phosphorylation are necessary for PMN-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction. The inhibition of Src caused Src/β-catenin disassociation and blocked PMN-induced β-catenin tyrosine phosphorylation in cultured endothelial cells. Src kinase may directly phosphorylate β-catenin in response to activated PMNs; this event leads to the disorganization of cell-to-cell adherens junction and ultimately endothelial barrier dysfunction [127]. Although Src activation is involved in increased endothelial permeability [4,23,127], its role in activating endothelial transcytosis following PMN activation remains unclear. Since Src-dependent caveolin-1 phosphorylation is a key switch in albumin endocytosis and transcytosis through the endothelium, it is likely that activation of PMNs may stimulate transcellular albumin transport via the Src dependent pathway. The contribution of endothelial transcytosis in the mechanism of increased lung microvessel permeability remains to be addressed.

5. Pharmacological perspectives and conclusion

In recent years, investigations of Src signaling in vascular endothelial permeability regulation have led to newer and more sophisticated methods to probe the molecular mechanisms involved. Indeed, as discussed above, there is now evidence to support the concept that SFKs are key regulators of the vascular endothelial barrier. This area of research warrants further investigation, as pharmacological inhibitors that selectively block individual Src family members may represent novel therapeutic approaches for limiting vascular leakage. However, due to the lack of selectivity of inhibitors of SFKs and the involvement of SFKs in many cellular activities, a strategy for the treatment of Src-mediated vascular leakage is not yet available. For instance, c-Src-and Yes-deficient mice show a negligible VEGF-induced vascular permeability response, yet Fyn-deficient mice display normal permeability responses [132]. Gene knockout and selective siRNA targeting of different isoforms of Src are needed to elucidate the role of SFKs in different types of inflammatory vascular leakage and in various cell types.

Transcellular transport is the primary mechanism by which albumin, lipids, steroid hormones, fat-soluble vitamins, and other substances that bind avidly to albumin cross the normally restrictive microvessel barrier lined with continuous endothelia. However, the importance of this pathway as a mechanism of protein leakage in pathological conditions remains to be investigated. Src signaling may play a critical role in proinflammatory mediator-induced transvascular hyperpermeability. In this regard, strategies directed against preventing Src-mediated increase in transcellular permeability via caveolae may be useful in reversing the accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the lung extravascular space. These studies could also lead to novel drug therapies for treatment of many diseases including acute lung injury and ARDS that target the transcellular permeability pathway in endothelial cells.

In summary, we believe that further insight into the regulatory mechanisms of Src signaling that contribute to endothelial hyperpermeability will help us to understand how this pathologic process can be treated. Understanding the role of Src in the various forms of vascular leakage that occurs during the different stages of inflammation will provide novel targets against increased paracellular and/or transcellular permeability for therapeutic intervention in inflammatory diseases.

6. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL71626 and HL60678), and the American Heart Association (0730331N).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

7. References

- 1.Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lum H, Malik AB. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 1994;267:L223–L241. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.3.L223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eliceiri BP, Puente XS, Hood JD, Stupack DG, Schlaepfer DD, Huang XZ, Sheppard D, Cheresh DA. Src-mediated coupling of focal adhesion kinase to integrin αvβ5 in vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. J. Cell. Biol. 2002;157:149–160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan SY. Protein kinase signaling in the modulation of microvascular permeability. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2002;39:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shyy JY, Chien S. Role of integrins in endothelial mechanosensing of shear stress. Circ. Res. 2002;91:769–775. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000038487.19924.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okutani D, Lodyga M, Han B, Liu M. Src protein tyrosine kinase family and acute inflammatory responses. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2006;29:L129–L141. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00261.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin GS. The hunting of the Src. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:467–75. doi: 10.1038/35073094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubbard SR, Till JH. Protein tyrosine kinase structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:373–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S, Garcia JG, Roy S, Parinandi NL, Natarajan V. Involvement of c-Src in diperoxovanadate-induced endothelial cell barrier dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279:L441–L451. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.3.L441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlessinger J. New roles for Src kinases in control of cell survival and angiogenesis. Cell. 2000;100:293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng XM, Resnick RJ, Shalloway D. A phosphotyrosine displacement mechanism for activation of Src by PTPα. EMBO J. 2000;19:964–978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roskoski R., Jr. Src protein-tyrosine kinase structure and regulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;324:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luttrell LM, Hawes BE, van Biesen T, Luttrell DK, Lansing TJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Role of c-Src tyrosine kinase in G protein-coupled receptor- and Gbetagamma subunit-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:19443–19450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bull HA, Brickell PM, Dowd PM. Src-related protein tyrosine kinases are physically associated with the surface antigen CD36 in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1994;351:41–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiefer F, Anhauser I, Soriano P, Aguzzi A, Courtneidge SA, Wagner EF. Endothelial cell transformation by polyomavirus middle T antigen in mice lacking Src-related kinases. Curr. Biol. 1994;4:100–109. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(94)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rankin S, Rozengurt E. Platelet-derived growth factor modulation of focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK) and paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation in Swiss 3T3 cells. Bell-shaped dose response and cross-talk with bombesin. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:704–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abu-Ghazaleh R, Kabir J, Jia H, Lobo M, Zachary I. Src mediates stimulation by vascular endothelial growth factor of the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase at tyrosine 861, and migration and anti-apoptosis in endothelial cells. Biochem. J. 2001;360:255–264. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abedi H, Zachary I. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation and recruitment to new focal adhesions of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:15442–15451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mucha DR, Myers CL, Schaeffer RC., Jr. Endothelial contraction and monolayer hyperpermeability are regulated by Src kinase. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;284:H994–H1002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00862.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaphorst KL, Pavalko FM, Patterson CE, Garcia JG. Thrombin-mediated focal adhesion plaque reorganization in endothelium: role of protein phosphorylation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1997;17:443–455. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.4.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koss M, Pfeiffer GR, II, Wang Y, Thomas ST, Yerukhimovich M, Gaarde WA, Doerschuk CM, Wang Q. Ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins are phosphorylated by TNF-alpha and modulate permeability increases in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1218–1227. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia JG, Verin AD, Schaphorst K, Siddiqui R, Patterson CE, Csortos C, Natarajan V. Regulation of endothelial cell myosin light chain kinase by Rho, cortactin, and p60(Src) Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:L989–998. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.6.L989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudek SM, Birukov KG, Zhan X, Garcia JG. Novel interaction of cortactin with endothelial cell myosin light chain kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;298:511–519. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02492-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dejana E. Endothelial aherens junctions:implications in the control of vascular permeability and angiogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:1949–1953. doi: 10.1172/JCI118997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lampugnani MG, Corada M, Caveda L, Breviario F, Ayalon O, Geiger B, Dejana E. The molcular organization of endothelial cell to cell junctions: differential association of plakoglobin, beta-catenin, and alpha-catenin with vascular cadherin (VE-cadherin) J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:203–217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong RK, Baldwin AL, Heimark RL. Cadherin-5 redistribution at sites of TNF-α and IFN-γ-induced permeability in mesenteric venules. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1999;276:H736–H748. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamaguchi M, Matsuyoshi N, Ohnishi Y, Gotoh B, Takeichi M, Nagai Y. p60v-Src causes tyrosine phosphorylation and inactivation of the N-cadherin-catenin call adhesion system. EMBO J. 1993;12:307–314. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behrens J, Vakaet L, Friis R, Winterhager E, Roy FV, Mareel MM, Birchmeier W. Loss of epithelial differentiation and gain of invasiveness correlates with tyrosine phosphorylation of the E-cadherin/ β-catenin complex in cells transformed with a temperature-sensitive v-SRC gene. J. Cell Biol. 1993;120:757–766. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carmeliet P, Lampugnani MG, Moons L, Breviario F, Compernolle V, Bono F, Balconi G, Spagnuolo R, Oostuyse B, Dewerchin M, Zanetti A, Angellilo A, Mattot V, Nuyens D, Lutgens E, Clotman F, de Ruiter MC, Gittenberger-de Groot A, Poelmann R, Lupu F, Herbert JM, Collen D, Dejana E. Targeted deficiency or cytosolic truncation of the VE-cadherin gene in mice impairs VEGF-mediated endothelial survival and angiogenesis. Cell. 1999;98:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lampugnani MG, Zanetti A, Breviario F, Balconi G, Orsenigo F, Corada M, Spagnuolo R, Betson M, Braga V, Dejana E. VE-cadherin regulates endothelial actin activating Rac and increasing membrane association of Tiam. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:1175–1189. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suarez S, Ballmer-Hofer K. VEGF transiently disrupts gap junctional communication in endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 2001:1229–1235. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drab M, Verkade P, Elger M, Kasper M, Lohn M, Lauterbach B, Menne J, Lindschau C, Mende F, Luft FC, Schedl A, Haller H, Kurzchalia TV. Loss of caveolae, vascular dysfunction, and pulmonary defects in caveolin-1 gene-disrupted mice. Science. 2001;293:2449–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1062688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Razani B, Engelman JA, Wang XB, Schubert W, Zhang XL, Marks CB, Macaluso F, Russell RG, Li M, Pestell RG, Di Vizio D, Hou H, Jr., Kneitz B, Lagaud G, Christ GJ, Edelmann W, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 null mice are viable but show evidence of hyperproliferative and vascular abnormalities. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:38121–38138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schubert W, Frank PG, Razani B, Park DS, Chow CW, Lisanti MPMP. Caveolae-deficient endothelial cells show defects in the uptake and transport of albumin in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48619–48622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minshall RD, Tiruppathi C, Vogel SM, Niles WD, Gilchrist A, Hamm HE, Malik AB. Endothelial cell-surface gp60 activates vesicle formation and trafficking via Gi-coupled Src kinase signaling pathway. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1057–1070. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shajahan AN, Tiruppathi C, Smrcka AV, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Gβγ activation of Src induces caveolae-mediated endocytosis in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48055–48062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shajahan AN, Timblin BK, Sandoval R, Tiruppathi C, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Role of Src-induced dynamin-2 phosphorylation in caveolae-mediated endocytosis in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20392–20400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiruppathi C, Song W, Bergenfeldt M, Sass P, Malik AB. Gp60 activation mediates albumin transcytosis in endothelial cells by tyrosine kinase-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25968–25975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glenney JR., Jr. Tyrosine phosphorylation of a 22-kDa protein is correlated with transformation by Rous sarcoma virus. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:20163–20166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S, Seitz R, Lisanti MP. Phosphorylation of caveolin by Src tyrosine kinases. The α-isoform of caveolin is selectively phosphorylated by v-Src in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:3863–3868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conner SD, Schmid SL. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 2003;422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parton RG, Joggerst B, Simons K. Regulated internalization of caveolae. J. Cell Biol. 1994;127:1199–1215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tinsley JH, Teasdale NR, Yuan SY. Involvement of PKCδ and PKD in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell hyperpermeability. Am. J Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C105–111. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00340.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu HM, Yuan Y, Zawieja DC, Tinsley J, Granger HJ. Role of phospholipase C, protein kinase C, and calcium in VEGF-induced venular hyperpermeability. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:H535–542. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dudek SM, Garcia JGN. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary permeability. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:1487–1500. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abid MR, Guo S, Minami T, Spokes KC, Ueki K, Skurk C, Walsh K, Aird WC. Vascular endothelial growth factor activates PI3K/Akt/forkhead signaling in endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:294–300. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000110502.10593.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ukropec JA, Hollinger MK, Salva SM, Woolkalis MJ. SHP2 association with VE-cadherin complexes in human endothelial cells is regulated by thrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:5983–5986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tar K, Csortos C, Czikora I, Olah G, Ma SF, Wadgaonkar R, Gergely P, Garcia JG, Verin AD. Role of protein phosphatase 2A in the regulation of endothelial cell cytoskeleton structure. J. Cell Biochem. 2006;98:931–953. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holinstat H, Knezevic N, Broman M, Samarel AM, Malik AB, Mehta D. Suppression of RhoA activity by focal adhesion kinase-induced activation of p190RhoGAP: role in regulation of endothelial permeability. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:2296–305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harrington EO, Shannon CJ, Morin N, Rowlett H, Murphy C, Lu Q. PKCδ regulates endothelial basal barrier function through modulation of RhoA GTPase activity. Exp. Cell Res. 2005;308:407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pelkmans L, Zerial M. Kinase-regulated quantal assemblies and kiss-and-run recycling of caveolae. Nature. 2005;436:128–133. doi: 10.1038/nature03866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Milici AJ, Watrous NE, Stukenbrok H, Palade GE. Transcytosis of albumin in capillary endothelium. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:2603–2612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Predescu D, Palade GE. Plasmalemmal vesicles represent the large pore system of continuous microvascular endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:H725–H733. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.2.H725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Predescu D, Horvat R, Predescu S, Palade GE. Transcytosis in the continuous endothelium of the myocardial microvasculature is inhibited by N-ethylmaleimide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:3014–3018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Predescu D, Predescu S, Malik AB. Transport of nitrated albumin across continuous vascular endothelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:13932–13937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212253499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Predescu D, Vogel SM, Malik AB. Functional and morphological studies of protein transcytosis in continuous endothelia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2004;287:L895–901. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00075.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schnitzer JE, Oh P. Albondin-mediated capillary permeability to albumin. Differential role of receptors in endothelial transcytosis and endocytosis of native and modified albumins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:6072–6082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim D, Duran WN. Platelet-activating factor stimulates protein tyrosine kinase in hamster cheek pouch microcirculation. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:H399–H403. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.1.H399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Delft S, Vermeer MA, Collard JG, van Hinsbergh VW. Activation of RhoA by thrombin in endothelial hyperpermeability: role of Rho kinase and protein tyrosine kinases. Circ. Res. 2000;87:335–340. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi S, Verin AD, Schaphorst KL, Gilbert-McClain LI, Patterson CE, Irwin RP, Natarajan V, Garcia JG. Role of tyrosine phosphorylation in thrombin-induced endothelial cell contraction and barrier function. Endothelium. 1998;6:153–171. doi: 10.3109/10623329809072202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wysolmerski RB, Lagunoff D. Involvement of myosin light-chain kinase in endothelial cell retraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:16–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schnittler HJ, Wilke A, Gress T, Suttorp N, Drenckhahn D. Role of actin and myosin in the control of paracellular permeability in pig, rat and human vascular endothelium. J. Physiol. 1990;431:379–401. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garcia JGN, Davis HW, Patterson CE. Regulation of endothelial cell gap formation and barrier dysfunction: role of myosin light chain phosphorylation. J. Cell Physiol. 1995;163:510–522. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goeckeler ZM, Wysolmerski RB. Myosin light chain kinase-regulated endothelial cell concentration: the relationship between isometric tension, actin polymerization, and myosin phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130:613–627. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moy AB, Van Engelenhoven J, Bodmer J, Kamath J, Keese C, Giaever I, Shasby S, Shasby DM. Histamine and thrombin modulate endothelial focal adhesion through centripetal and centrifugal forces. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:1020–1027. doi: 10.1172/JCI118493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rabiet MJ, Plantier JL, Rival Y, Genoux Y, Lampugnani MG, Dejana E. Thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability is associated with changes in cell-to-cell junction organization. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996;16:488–496. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gardner TW, Lesher T, Khin S, Vu C, Barber AJ, Brennan WA. Histamine reduces ZO-1 tight-junction protein expression in cultured retinal microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem. J. 1996;320:717–721. doi: 10.1042/bj3200717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tiruppathi C, Minshall RD, Paria BC, Vogel SM, Malik AB. Role of Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of endothelial permeability. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2003;39:173–185. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Birukova AA, Smurova K, Birukov KG, Kaibuchi K, Garcia JGN, Verin AD. Role of Rho GTPases in thrombin-induced lung vascular endothelial cell barrier function. Microvasc. Res. 2004;67:64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sandoval R, Malik AB, Minshall RD, Kouklis P, Ellis CA, Tiruppathi C. Ca2+ signaling and PKCα activate increased endothelial permeability by disassembly of VE- cadherin junctions. J. Physiol. (Lond) 2001;533:433–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0433a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dejana E, Bazzoni G, Lampugnani MG. Vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin: only an intercellular glue? Exp. Cell Res. 1999;252:13–19. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Del Maschio A, Zanetti A, Corada M, Rival Y, Ruco L, Lampugnani MG, Dejana E. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte adhesion triggers the disorganization of endothelial cell-to-cell adherens junctions. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Riveline D, Zamir E, Balaban NQ, Schwarz US, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Kam Z, Geiger B, Bershadsky AD. Focal contacts as mechanosensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1175–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Luscinskas FW, Lawler J. Integrins as dynamic regulators of vascular function. FASEB J. 1994;8:929–938. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.12.7522194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sheetz MP. Cell control by membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:392–396. doi: 10.1038/35073095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu MH, Ustinova E, Granger HJ. Integrin binding to fibronectin and vitronectin maintains the barrier function of isolated porcine coronary venules. J. Physiol. 2001;532:785–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0785e.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schlaepfer DD, Hauck CR, Sieg DJ. Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1999;71:435–478. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schaller MD. Biochemical signals and biological responses elicited by the focal adhesion kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1540:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schaller MD, Borgman CA, Parsons JT. Autonomous expression of a noncatalytic domain of the focal adhesion-associated protein tyrosine kinase pp125FAK. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;13:785–791. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lambeng N, Wallez Y, Rampon C, Cand F, Christe G, Gulino-Debrac D, Vilgrain I, Huber P. Vascular endothelial-cadherin tyrosine phosphorylation in angiogenic and quiescent adult tissues. Circ. Res. 2005;96:384–391. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156652.99586.9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Abedi H, Dawes KE, Zachary I. Differential effects of platelet-derived growth factor BB on p125 focal adhesion kinase and paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation and on cell migration in rabbit aortic vascular smooth muscle cells and Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:11367–11376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bazzoniand G, Dejana E. Pores in the sieve and channels in the wall: control of paracellular permeability by junctional proteins in endothelial cells. Microcirculation. 2001;8:143–152. doi: 10.1038/sj/mn/7800084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix–cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:793–805. doi: 10.1038/35099066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Birukov KG, Csortos C, Marzilli L, Dudek S, Ma SF, Bresnick AR, Verin AD, Cotter RJ, Garcia JG. Differential regulation of alternatively spliced endothelial cell myosin light chain kinase isoforms by p60(Src) J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:8567–8573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aberle H, Schwartz H, Kemler R. Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J. Cell Biochem. 1996;61:514–523. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960616)61:4%3C514::AID-JCB4%3E3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alexander JS, Alexander BC, Eppihimer LA, Goodyear N, Haque R, Davis CP, Kalogeris TJ, Carden DL, Zhu YN, Kevil CG. Inflammatory mediators induce sequestration of VE-cadherin in cultured human endothelial cells. Inflammation. 2000;24:99–113. doi: 10.1023/a:1007025325451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miyamoto S, Teramoto MM, Coso OA, Gutkind JS, Burbelo PD, Akiyama SK, Yamada KM. Integrin function: molecular hierarchies of cytoskeletal and signaling molecules. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:791–805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stan RV. Structure and function of endothelial caveolae. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2002;57:350–364. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pelkmans L, Helenius A. Endocytosis via caveolae. Traffic. 2002;3:311–320. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rippe B, Rosengren BI, Carlsson O, Venturoli DD. Transendothelial transport: the vesicle controversy. J. Vasc. Res. 2002;39:375–390. doi: 10.1159/000064521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tuma PL, Hubbard AL. Transcytosis: crossing cellular barriers. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:871–932. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Frank PG, Woodman SE, Park DS, Lisanti MP. Caveolin, caveolae, and endothelial cell function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:1161–1168. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000070546.16946.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barchowsky A, Munro SR, Morana SJ, Vincenti MP, Treadwell M. Oxidant-sensitive and phosphorylation-dependent activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 1995;269:L829–L836. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.6.L829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hardwick JS, Sefton BM. Activation of the lck tyrosine protein kinase by H2O2 requires the phosphorylation of tyr-394. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:4527–4531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nakamura K, Hori T, Sato N, Sugie K, Kawakami T, Yodoi JJ. Redox regulation of a Src family protein tyrosine kinase p56lck in T cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:3133–3139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giannoni E, Buricchi F, Raugei G, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. Intracellular reactive oxygen species activate Src tyrosine kinase during cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:6391–6403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6391-6403.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rhee SG. Cell signaling, H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kevil CG, Okayama N, Alexander JS. H2 O2 -mediated permeability II: importance of tyrosine phosphatase and kinase activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1940–1947. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Johnson A, Phillips P, Hocking D, Tsan MF, Ferro T. Protein kinase inhibitor prevents pulmonary edema in response to H2O2. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1989;256:H1012–H1022. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mark KS, Miller DW. Increased permeability of primary cultured brain microvessel endothelial cell monolayers following TNF-α exposure. Life Sci. 1999;64:1941–1953. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nwariaku FE, Liu Z, Zhu X, Turnage RH, Sarosi GA, Terada LS. Tyrosine phosphorylation of vascular endothelial cadherin and the regulation of microvascular permeability. Surgery. 2002;132:180–185. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.125305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Aikawa R, Komuro I, Yamazaki T, Zou Y, Kudoh S, Tanaka M, Shiojima I, Hiroi Y, Yazaki Y. Oxidative stress activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases through Src and Ras in cultured cardiac myocytes of neonatal rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:1813–1821. doi: 10.1172/JCI119709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nishida M, Maruyama Y, Tanaka R, Kontani K, Nagao T, Kurose H. Gαi and Gαo are target proteins of reactive oxygen species. Nature. 2000;408:492–495. doi: 10.1038/35044120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rahman A, Bando M, Kefer J, Anwar KN, Malik AB. Protein kinase C-activated oxidant generation in endothelial cells signals intracellular adhesion molecule-1 gene transcription. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:575–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rahman A, Kefer J, Bando M, Niles WD, Malik AB. E-selectin expression in human endothelial cells by TNF-α-induced oxidant generation and NF-κB activation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 1998;275:L533–L544. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.3.L533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Pathophysiological consequences of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Nature. 2005;437:497–504. doi: 10.1038/nature03987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Eliceiri BP, Paul R, Schwartzberg PL, Hood JD, Leng J, Cheresh DA. Selective requirement for Src kinases during VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:915–924. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gavard J, Gutkind JS. VEGF controls endothelial-cell permeability by promoting the β-arrestin-dependent endocytosis of VE-cadherin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:1223–1234. doi: 10.1038/ncb1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Weis S, Shintani S, Weber A, Kirchmair R, Wood M, Cravens A, McSharry H, Iwakura A, Yoon YS, Himes N, Burstein D, Doukas J, Soll R, Losordo D, Cheresh D. Src blockade stabilizes a Flk/cadherin complex, reducing edema and tissue injury following myocardial infarction. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:885–894. doi: 10.1172/JCI20702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chou MT, Wang J, Fujita DJ. Src kinase becomes preferentially associated with the VEGFR, KDR/Flk-1, following VEGF stimulation of vascular endothelial cells. BMC Biochem. 2002;3:32–42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-3-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Esser S, Lampugnani MG, Corada M, Dejana E, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces VE-cadherin tyrosine phosphorylation in endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:1853–1865. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.13.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chiariello M, Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS. Regulation of c-myc expression by PDGF through Rho GTPases. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:580–586. doi: 10.1038/35078555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Luttrell LM, Ferguson SS, Daaka Y, Miller WE, Maudsley S, Rocca G.J. Della, Lin F, Kawakatsu H, Owada K, Luttrell DK, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. β-arrestin-dependent formation of β2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science. 1999;283:655–661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Palacios F, Tushir JS, Fujita Y, D’Souza-Schorey C. Lysosomal targeting of E-cadherin: a unique mechanism for the down-regulation of cell-cell adhesion during epithelial to mesenchymal transitions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:389–402. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.389-402.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hanke JH, Gardner JP, Dow RL, Changelian PS, Brissette WH, Weringer EJ, Pollok BA, Connelly PA. Discovery of a novel, potent, and Src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Study of Lck- and FynT-dependent T cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:695–701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tiruppathi C, Naqvi T, Sandoval R, Mehta D, Malik AB. Synergistic effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and thrombin in increasing endothelial permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2001;281:L958–968. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.4.L958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sandoval R, Malik AB, Naqvi T, Mehta D, Tiruppathi C. Requirement of Ca2+ signaling in the mechanism of thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2001;280:L239–L247. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.2.L239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Freichel M, Suh SH, Pfeifer A, Schweig U, Trost C, Weibgerber P, Biel M, Philip S, Freise D, Droogmans G, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Nilius B. Lack of an endothelial store-operated Ca2+ current impairs agonist-dependent vasorelaxation in TRP4−/− mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:121–127. doi: 10.1038/35055019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Moore TM, Brough GH, Babal P, Kelly JJ, Li M, Stevens T. Store-operated calcium entry promotes shape change in pulmonary endothelial cells expressing Trp1. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 1998;275:L574–L582. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.3.L574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ma HT, Patterson RL, van Rossum DB, Birnbaumer L, Mikoshiba K, Gill DL. Requirement of inositol trisphosphate receptor for activation of store-operated Ca2+channels. Science. 2000;287:1647–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Putney JW. TRP, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors, and capacitative calcium entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:14669–14671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Laposata M, Dovnarsky DK, Shin HS. Thrombin-induced gap formation in confluent endothelial cell monolayers in vitro. Blood. 1983;62:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chin AC, Vergnolle N, MacNaughton WK, Wallace JL, Hollenberg MD, Buret AG. Proteinase-activated receptor 1 activation induces epithelial apoptosis and increases intestinal permeability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:11104–1109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831452100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lo SK, Everitt J, Gu J, Malik AB. Tumor necrosis factor mediates experimental pulmonary edema by ICAM-1 and CD18-dependent mechanisms. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:981–988. doi: 10.1172/JCI115681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lindbom L. Regulation of vascular permeability by neutrophils in acute inflammation. Chem. Immunol. Allergy. 2003;83:146–166. doi: 10.1159/000071559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tinsley JH, Ustinova EE, Xu W, Yuan SY. Src-dependent, neutrophil-mediated vascular hyperpermeability and β-catenin modification. Am. J. Physiol. 2002;283:C1745–1751. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00230.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lin P, Welch EJ, Gao XP, Malik AB, Ye RD. Lysophosphatidylcholine modulates neutrophil oxidant production through elevation of cyclic AMP. J. Immunol. 2005;174:2981–2989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sano H, Nakagawa N, Chiba R, Kurasawa K, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. Cross-linking of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 induces interleukin-8 and RANTES production through the activation of MAP kinases in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;250:694–698. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Durieu-Trautmann O, Chaverot N, Cazaubon S, Strosberg AD, Couraud PO. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 activation induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the cytoskeleton-associated protein cortactin in brain microvessel endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:12536–12540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Doerschuk CM, Quinlan WM, Doyle NA, Bullard DC, Vestweber D, Jones ML, Takei F, Ward PA, Beaudet AL. The role of P-selectin and ICAM-1 in acute lung injury as determined using blocking antibodies and mutant mice. J. Immunol. 1996;157:4609–4614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Hinsbergh VW. Targets for pharmacological intervention of endothelial hyperpermeability and barrier function. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2002;39:257–272. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]