Abstract

NKG2D is a stimulatory receptor expressed by NK cells and some T cell subsets. Expression of the self-encoded ligands for NKG2D is presumably tightly regulated to prevent autoimmune disorders while allowing detection of infected cells and developing tumors. The NKG2D ligand Mult1 is regulated at multiple levels with a final layer of regulation controlling protein stability. Here we report that Mult1 cell surface expression was prevented by two closely related E3 ubiquitin ligases, MARCH4 and MARCH9, members of an E3 family that regulates other immunologically active proteins. Lysines within the cytoplasmic domain of Mult1 were essential for this repression by MARCH4 or MARCH9. Downregulation of Mult1 by MARCH9 was reversed by heat shock treatment, which resulted in the dissociation of the two proteins and increased the amount of Mult1 at the cell surface. These results identify Mult1 as a new target for the MARCH family of E3 ligases, and show that induction of Mult1 in response to heat shock is due to regulated association with its E3 ligases.

Introduction

NKG2D is a receptor expressed by NK cells and subsets of T cells. When engaged by cellular ligands, NKG2D initiates stimulatory signaling cascades by virtue of its association with the signaling adaptor molecules DAP10 and/or DAP12. Stimulation of immune cells through NKG2D has been shown to be involved in protective responses to infections and tumors (1, 2), but also can lead to autoimmunity (3). Therefore, the regulation of activating signals through NKG2D is extremely important in order to protect the host from pathogens and tumors while at the same time preventing destruction of self-tissue. The NKG2D receptor is constitutively expressed on NK cells and some T cells, and the regulation of the NKG2D-mediated response occurs largely at the level of ligand expression.

The ligands for NKG2D are self-proteins that are absent or expressed at a low level on most normal tissues. There are nine known murine ligands (Rae1ãRae1e, H60a-H60c, and Mult1) and nine known human ligands (RAET1a-RAET1g [also known as ULPBs], MICA, and MICB) that are all distantly related to MHC class I. Due to their relatively rapid rate of evolution, however, it has not been possible to draw direct lines of homology between individual mouse and human ligands (4). Though induction of the ligands is known to occur on tumor cells and during certain infections, the mechanisms regulating this induction are still being characterized. Stress pathways, most notably the DNA damage and heat shock pathways, have been shown to induce ligand expression on cell lines in vitro (5, 6). While the DNA damage response pathway was shown to regulate many of the NKG2D ligands similarly, the heat shock pathway acts more selectively on a subset of ligands, MICA/B in humans and Mult1 in mice. Heat shock regulation differs in the latter two cases however. Whereas MICA/B are thought to be regulated transcriptionally by the heat shock response, Mult1 was shown to be induced as a consequence of heat-shock mediated suppression of the high steady state ubiquitination and turnover of Mult1 (7).

In order to better understand the molecular mechanism of post-translational Mult1 regulation, it is important to identify E3 ubiquitin ligases that target Mult1. E3 ubiquitin ligases are, in most cases, non-catalytic scaffolds that bring a ubiquitin-bearing E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme in close proximity to a target allowing the transfer of ubiquitin to occur (8). Thus, target specificity of ubiquitination reactions are most often determined by an E3. The membrane-associated RING-CH (MARCH) family of E3 ligases (9, 10) represented a promising set of candidate Mult1 regulatory proteins for several reasons. MARCH proteins are transmembrane proteins, and most of their targets identified so far are also transmembrane proteins, many with significance to the immune system (9, 11-15). Of particular interest is the finding that MHC class I expression is regulated by ubiquitination dependent on the MARCH4 and MARCH9 E3 ligases, as well as by virally encoded homologues of the MARCH proteins, MIR1 and MIR2 (9, 16). MHC class II is also ubiquitinated by MARCH proteins, MARCH1 and MARCH8, and regulation of this ubiquitination pathway is involved in the induction of MHC II expression on dendritic cells upon activation (11, 17).

While the mechanism determining substrate recognition has not been determined for all the endogenous MARCH proteins, the substrate specificity of MIR2 has been shown through domain swapping to be dependent on their membrane spanning regions (18). Since the transmembrane domain of Mult1 is involved in its protein-level regulation (7) and Mult1 has homology to MHC class I, the MARCH proteins were prime candidates for Mult1 E3 ligases. This initial suspicion for a role of MARCH proteins in regulating Mult1 was bolstered by a recent report that the viral homolog MIR2 downregulates the human NKG2D ligands MICA and MICB (19). In this report, we provide direct evidence that MARCH4 and MARCH9, but not other MARCH proteins, can associate with Mult1 and suppress Mult1 expression at the cell surface in a manner that depends on lysine residues in the Mult1 cytoplasmic domain, and that can be reversed by heat shocking the cells.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Heat Shock

All cells were cultured in complete DMEM, consisting of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Gibco), 10% fetal calf serum (Omega Scientific), 100 U/ml penicillin (Gibco), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), 0.2 mg/ml glutamine (Sigma), 10 μg/ml gentamycin sulfate (Lonza), 20 mM Hepes (Fisher), and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (EMD biosciences). Heat shock was performed by placing cells in a 45-degree waterbath for 30 minutes followed by a four-hour incubation at 37 degrees. Dead cells were excluded from flow cytometry analysis through staining with 7-AAD.

Cytotoxicity assay

Lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells were prepared by culturing splenocytes for 4-5 days in 1000U/mL IL-2. LAK cells were co-cultured with 51Cr-labeled target cells in a standard 4h 51Cr release assay (20).

Antibodies

Mult1 antibody (R+D Systems, clone 237104), H60a antibody (R+D Systems, clone 205326), HA antibody (Covance, HA.11), PE conjugated goat F(ab’)2 fragment to rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch), PE conjugated goat antibody to mouse IgG1 (Southern Biotech), PE conjugated MHC-I (H-2Db) antibody (ebioscience, clone 28-14-8), PE conjugated H-2Kb antibody (ebioscience, clone AF6-88.5), and PE conjugated ICAM-1 (ebioscience, clone YN1/1.7.4) were used for flow cytometric analysis. Mult1 antibody (clone 1D6, kind gift of S. Jonjic (21)) was used for immunoprecipitations and western blots. Ubiquitin antibody (clone P4D1, Santa Cruz), ãtubulin antibody (Calbiochem), myc antibody (ebioscience, clone 9E10), HA antibody (Covance, HA.11), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Pierce), and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse light chain (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used for western blots.

Cloning of MARCH cDNA

The human MARCH proteins were amplified from EST clones purchased from the ATCC collection and subcloned into pCGN-HA. Mouse MARCH4 and MARCH9 were amplified from mouse fibroblast cDNA using the following primers: BamHI-M4F (5′-CCAAAGGATCCCATGCTCATGCCCCTGGGTG-3′), HindIII-M4R (5′-CCAAAAAGCTTTCACACTGTGGTGACTCTCATGAC), BamHI-M9F5′ (5′-CCAAAGGATCCGATGCTCAAGTCTCGGCTCCG-3′), M9R5′ (5′-GAAGTA GCAAAGCTCACAGCTCCATG-3′), M9F3′ (5′-AAGTACCAGGTCCTGGCGATCAGC AC-3′), and HindIII-M9R3′ (5′-CCAAAAAGCTTTCAGACTGTGGTGACCCTCATG-3′). MARCH9 was cloned by assembling two amplified segments (5′ end amplified from genomic DNA) due to difficulty in achieving full-length amplification through the GC-rich 5′ end. Amplified mouse MARCH4 and MARCH9 products were subcloned into pCMV-TAG3a.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol LS (Invitrogen) followed by digestion of contaminating DNA using DNA-free (Ambion) according to manufacture’s protocol.

RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and the resulting cDNA was used for qPCR. Duplicate or triplicate amplification mixtures were prepared with 0.01-1 μg cDNA, SYBR GreenER SuperMix (Invitrogen), and 200 nM forward and reverse primers, and cycled using the ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR system. Cycling parameters used were 50 °C for 2 minutes, 95 °C for 10 minutes, and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 60 seconds. The following primers were used: Mult1-5′,5′-CAATGTCTCTGTCCTCGGAA-3′; Mult1-3′,5′-CTGAACACGTCTCAGGCACT-3′; MARCH4-5′, 5′-CTCTGGGAAGTAGCTTGGAC-3′; MARCH4-3′, 5′-CTGAACCATCACAACGGCATG-3′; MARCH9-5′, 5′-TCATGGAGCTGTGAGCTTTG-3′; MARCH9-3′, 5′-CAGGACGATAGCAGCAATCT-3′; RPS29-5′, 5′-AGCAGCTCTACTGGAGTCACC-3′; RPS29-3′, 5′-AGGTCGCTTAGTCCAACTTAATG-3′.

Retroviral constructs and transduction of cells

FLAG or HA-tagged Mult1 was cloned into the pMSCV2.2-IRES-GFP retroviral vector (22). Myc-tagged MARCH4 and MARCH9 were subcloned into pMSCV-IRES-Thy1.1. Mutants of Mult1 were made as described (7). Retroviral supernatants were generated by co-transfecting 293T cells with plasmids encoding VSV gag/pol and env and pMSCV retroviral constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Culture supernatants collected 48 hours after transfection were added directly to actively proliferating cells and transduced cells were sorted based on GFP or Thy1.1 expression.

Immunoprecipitation and western blotting

Lysates were prepared by resuspending cell pellets in co-immunoprecipitation buffer (0.5% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 10% glycerol). Protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche) were added to the buffer immediately before use. When assessing ubiquitination of Mult1, 20 mM N-ethylmalemide was included in the lysis buffer. Cells were lysed at 4 degrees for 30 minutes and cleared by centrifugation at 16,000xg for 15 minutes. Lysates were pre-cleared with protein G PLUS agarose beads (Santa Cruz). Pre-cleared lysates were incubated with 1 μg Mult1 antibody (1D6) for one hour followed by protein G agarose beads overnight. Beads were washed three times in lysis buffer and boiled in SDS sample buffer for separation by SDS-PAGE. Samples resolved by SDS-PAGE were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk and incubated with primary antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies. Following incubation with western lightning chemiluminescence reagent (Perkin Elmer), membranes were exposed to film and developed.

Transfection of siRNA oligos

Relative levels of MARCH4 and MARCH9 were determined using the primers MARCH4+9-5′ (5′-CAGTGGCAGGCCAT-3′) and MARCH4+9-3′(5′-CTTTCCACTGCTGGTT-3′) followed by digestion with SalI which selectively digests MARCH-4 amplicons. 50,000 fibroblasts were transfected with 100 pmol siRNA oligo using Lipofectamine 2000. The following oligos were used: GFP-22 (Qiagen), control oligo (Invitrogen), and three pre-designed MARCH9 oligos (Invitrogen). 72 hours later cells were lifted and used for analysis of Mult1 surface expression and MARCH-9 quantitative PCR.

Results

Screen of human MARCH proteins identifies MARCH4 and 9 as Mult1 E3 ligases

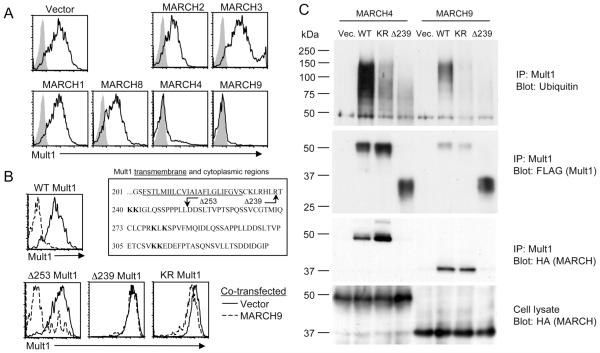

The nine mammalian MARCH proteins that were originally described can be distinguished based on the number of transmembrane domains they possess. MARCH1, MARCH2, MARCH3, MARCH4, MARCH8, and MARCH9 have two TMs and are most closely related to the viral homologues. Plasmids encoding HA-tagged versions of these two-TM MARCH proteins cloned from human cDNA were used to screen for the ability to regulate Mult1 expression. 293T cells were transiently co-transfected with individual hMARCH plasmids or control plasmid together with a plasmid encoding both Mult1 and GFP. Cells were stained 24 hours later with Mult1 antibodies and transfected cells were selectively analyzed by gating on GFP expressing cells. Strikingly, co-transfection of Mult1 with either of two highly related family members, hMARCH4 and hMARCH9, prevented Mult1 cell surface expression (Fig. 1A). This effect was specific to hMARCH4 and hMARCH9 because no other MARCH family members that were tested (MARCH6, MARCH7, MARCH10 or MARCH11 were not examined) caused notable variations in Mult1 expression compared to control cells. Interestingly, these two proteins were the same MARCH proteins reported to downregulate MHC class I molecules (9).

Figure 1. Screen of human MARCH proteins identifies MARCH4 and 9 as Mult1 E3 ligases.

293T cells were co-transfected with a plasmid encoding WT Mult1-IRES-GFP and a plasmid encoding the indicated human MARCH proteins. A, B. GFP positive cells were analyzed 24 hours after transfection by flow cytometry for Mult1 expression. Expression of GFP, which is encoded by the same bicistronic mRNA as Mult1, was similar in all the samples, indicating comparable Mult1 gene expression. Shaded grey histograms represent staining of cells transfected with a plasmid encoding IRES-GFP only. C. Cells were lysed in co-IP buffer followed by immunoprecipitation of Mult1 and detection of FLAG, HA, or ubiquitin by western blotting. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

To determine the role of the Mult1 cytoplasmic domain in MARCH9-mediated downregulation, 293T cells were co-transfected with Mult1 cytoplasmic domain mutants and hMARCH9 (Fig. 1B). hMARCH9 strongly inhibited cell surface expression of a Mult1 truncation mutant lacking amino acids 253-334 (the D253 mutant), showing that most of the cytoplasmic domain, containing four cytoplasmic lysine residues (K278, K280, K310, and K311), was not necessary for MARCH9-mediated downregulation. In contrast, hMARCH9 cotransfection did not impair cell surface expression of a Mult1 truncation mutant (the D239 mutant) lacking a slightly larger segment, comprising amino acids 239-334, including two additional cytoplasmic lysine residues (K240 and K241) compared to the D253 mutant. The role of the cytoplasmic lysine residues was confirmed by the demonstration that the KR mutant, a full length Mult1 in which all 6 cytoplasmic lysine residues were substituted with arginine residues, was only slightly downregulated by hMARCH9. The marginal downregulation of the KR mutant by hMARCH9 was reproducible, however, suggesting that non-lysine residues in the cytoplasmic domain may be suboptimal targets for MARCH9 mediated ubiquitination, as was previously demonstrated in the case of ubiquitination targeted by the other MARCH family proteins, MIR1, MK3, and MARCH2 (23, 24). Together, these results show that the Mult1 cytoplasmic domain is critical for downregulation by MARCH9, and that lysines within this domain are required for this regulation.

The requirement for lysine residues within the cytoplasmic domain strongly suggested that the downregulation of Mult1 by MARCH9 involved ubiquitination. To confirm that Mult1 is ubiquitinated by MARCH 4 and 9, Mult1 was immunoprecipitated from transfected 293T cells followed by detection of ubiquitin by western blotting. High molecular weight ubiquitin species were evident in immunoprecipitates from cells co-transfected with hMARCH4 or 9 and WT Mult1 but were notably less abundant when the KR or D239 Mult1 mutants were expressed (Fig. 1C). The fact that these ubiquitinated species were dependent on lysines in the Mult1 cytoplasmic domain, were absent in the vector-transfected cells, and were larger than Mult1 (55 kDa), strongly suggested that they represent ubiquitinated Mult1. Surprisingly, even though Mult1 was ubiquitinated and depleted from the cell surface in the presence of hMARCH4/9, there was no apparent decrease in total Mult1 protein levels seen by western blot (Fig. 1C). This finding suggests that the downregulation of Mult1 in the presence of MARCH4/9 in 293T cells is due to sequestration in an intracellular compartment.

It remained possible that the effect of MARCH4/9 on Mult1 expression was indirect, so co-immunoprecipitation of the two proteins was performed to measure the extent of their physical interaction. Mult1 was immunoprecipitated from co-transfected cells followed by western blotting to detect HA-tagged hMARCH proteins (Fig. 1C). Both hMARCH4 and hMARCH9 were co-immunoprecipitated with Mult1, showing that a physical interaction does occur. Stronger co-immunoprecipitation was evident in the case of hMARCH4, but this may be partly ascribed to a greater expression of hMARCH4 in the transfected cells (Fig. 1C, bottom panel). The interaction of Mult1 with the hMARCH proteins did not depend on the presence of lysines in the Mult1 cytoplasmic domain because hMARCH4 and hMARCH9 were co-immunoprecipitated with the KR mutant to the same extent as with WT Mult1. In contrast, hMARCH4/9 failed to co-immunoprecipitate appreciably with the D239 mutant of Mult1, indicating that the cytoplasmic domain, independent of the cytoplasmic lysine residues, might be important for allowing interaction with MARCH4 or MARCH9 to occur. Together, these data show that MARCH4 and 9 interact with Mult1 in a manner dependent on the Mult1 cytoplasmic domain, leading to its ubiquitination and reduced surface expression.

Mouse MARCH4/9 downregulate endogenous Mult1

Although the MARCH proteins are highly conserved between humans and mice, it was important to verify the results obtained with the human proteins using mouse MARCH4/9 in a more physiological experimental setting. Mouse MARCH4/9 were amplified from cDNA, N-terminally tagged with the myc epitope, and cloned into a MSCV retroviral expression vector. Retroviral transduction was utilized because it allowed stable ectopic expression at lower levels than transient transfection, thus minimizing potential non-specific effects of forced expression. Two cell lines, C1498 and WEHI 7.1, were chosen for ectopic expression of mouse MARCH4/9 because they express endogenous Mult1.

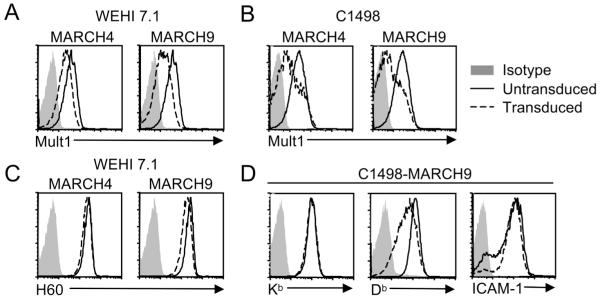

Stable expression of mouse MARCH4 or MARCH9 in either of these cell lines led to decreased cell surface expression of endogenous Mult1 (Fig. 2A, B), confirming that the mouse MARCH proteins downregulate Mult1. The downregulation of Mult1 was specific, because there was little or no downregulation of a distinct transmembrane NKG2D ligand that is normally expressed by WEHI 7.1 cells, H60a (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the endogenous Db class I MHC molecule was partially downregulated by mouse MARCH9 in CI498 cells, consistent with reports that transfected human MARCH4/9 downregulate MHC-I and ICAM-1 in human cells (Fig. 2D) (9, 12). On the other hand, mouse MARCH9 failed to downregulate ICAM-1 or a distinct MHC I molecule, Kb, in transfected C1498 cells, suggesting selectivity in the effects of mouse MARCH proteins compared to human MARCH proteins (Fig. 2D). Though the possibility remains that mouse MARCH9 regulates other transmembrane molecules not examined here in a more dramatic fashion, these results clearly show that targeting for downregulation by mouse MARCH9 is quite specific, and Mult1 is one of its targets.

Figure 2. Mouse MARCH4 and MARCH9 downregulate endogenous Mult1.

WEHI 7.1 (A, C) or C1498 (B, D) cells were transduced with retroviruses encoding mMARCH4 or mMARCH9. A co-expressed IRES-Thy1.1 cassette was used to mark transduced cells. Thy1.1 positive cells were sorted and analyzed for expression of Mult1 (A, B), H60a (C), Kb, Db, or ICAM-1 (D). Similar results were obtained in at least two additional experiments.

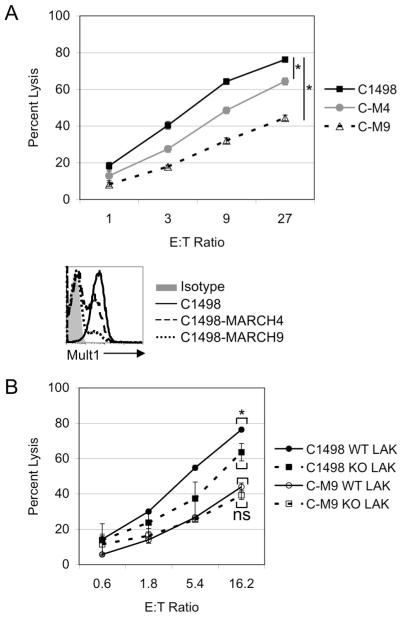

MARCH9 expression inhibits lysis by NK cells

To determine whether MARCH proteins regulate the susceptibility of target cells to NK mediated lysis, transduced C1498 cells were employed as target cells for activated NK cells (lymphokine-activated killer, or LAK cells). C1498 cells transduced with mMARCH4 or mMARCH9 were killed significantly less well by LAK cells than parental C1498 cells (Fig. 3A). A greater reduction in killing was observed with cells transduced with mMARCH9 as compared to mMARCH4, which correlated with a greater reduction in Mult1 in the former cells (Fig. 3A). However, even though mMARCH9-transduced cells were nearly devoid of cell surface Mult1, the cells retained partial sensitivity to LAK cell killing, presumably due to the presence of additional stimulatory ligands for NK cells on C1498 cells that are not downregulated by MARCH9.

Figure 3. MARCH9 expression inhibits lysis by NK cells.

A. Untransduced C1498 cells or C1498 cells transduced with mMARCH4 or mMARCH9 were used as targets for activated NK cells (LAK cells) in a chromium release assay. Target cells were analyzed for Mult1 expression by flow cytometry. B. C1498 or C1498-MARCH9 cells were used as targets for LAK cells prepared from WT or NKG2D knockout mice in a chromium release assay. * indicates a p-value of <0.05, ns = not significant, C-M4 = C1498-MARCH4 cells, C-M9 = C1498-MARCH9 cells. Results are representative of at least two independent experiments.

To determine the component of the reduced killing that was due to downregulation of Mult1, we compared killing by LAK cells prepared from wildtype or NKG2D knockout mice. Parental C1498 cells were killed significantly though modestly less well by NKG2D-deficient LAK cells than by WT LAK cells. Since C1498 cells express Mult1 but not other NKG2D ligands (data not shown), these data suggested that Mult1 contributed significantly to NK killing of C1498 cells, but that ligands for other activating receptors also played a large role, as was true of most target cell lines studied elsewhere (20). In contrast, C1498-MARCH9 cells were killed equally well by WT or NKG2D-deficient LAK cells, showing that removal of Mult1 from the cell surface did indeed prevent NKG2D-dependent killing. It was notable, however, that the reduction in killing accomplished by MARCH9 transduction was greater than the reduction in killing of parental C1498 cells resulting from NKG2D-deficiency. Therefore it is likely that MARCH9-transduction downregulated ligands for other activating NK receptors, in addition to downregulating Mult1. The identity of the other affected ligands in our analysis remains unclear, but there are numerous NK activating ligands some of which may remain to be identified. The affected ligands are probably not ICAM-1, CD48 (ligand for 2B4) or CD155 (ligand for DNAM-1), because we observed no ICAM-I downregulation in MARCH9 transduced cells (Fig. 2D), and did not detect CD48 or CD155 expression on C1498 cells (data not shown). The possibility that NK stimulatory and inhibitory ligands other than Mult1 are also targets of MARCH9 was suggested by published data (9, 12, 15). Together, these data show that MARCH9-mediated downregulation of Mult1 and probably other activating ligands on C1498 cells inhibits functional recognition by NK cells.

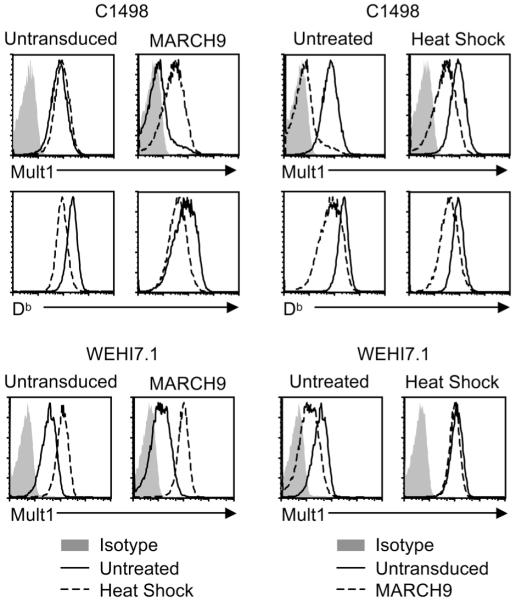

MARCH9 and regulation of Mult1 by heat shock

In some cell types including WEHI 7.1, a fibroblast cell line, and a subset of primary thymocytes, expression of Mult1 has been shown to be inducible by heat shock (Fig. 4, (7)). In contrast, wildtype CI498 cells normally express somewhat higher levels of cell surface Mult1, and no increase was observed after the cells were subjected to heat shock (Fig. 4). The reason that Mult1 is not regulated by heat shock in C1498 cells is not known, but transduction of mMARCH9 into C1498 cells greatly reduced the high basal level of Mult1, raising the possibility that MARCH9 restored a missing component in the pathway regulating Mult1. Indeed, when mMARCH9-transduced C1498 cells were heat shocked, substantial levels of Mult1 were restored to the cell surface whereas little change in Mult1 expression was seen on parental C1498 cells (Fig. 4). These data suggest that the parental C1498 cells lack an E3 ligase for Mult1, and this defect is rescued by ectopic expression of MARCH9.

Figure 4. MARCH9 and regulation of Mult1 by heat shock.

WEHI 7.1 and C1498 cells transduced with mMARCH9, or not, were heat shocked at 45 degrees for 30 minutes followed by a four-hour incubation at 37 degrees. Expression of Mult1 and Db were analyzed by flow cytometry. Panels on the left and right are organized to show the relative effects of MARCH9 and heat shock, respectively. Similar results were obtained in at least two additional experiments.

As noted already, cell surface expression of the MHC I molecule Db was diminished by transduction of mMARCH9 in C1498 cells, so it appears to be a target of MARCH9. Strikingly, however, Db, unlike Mult1, was not induced by heat shock in mMARCH9-transduced C1498 cells. In fact, for unknown reasons, heat shock caused a reduction in Db levels at the cell surface in both mMARCH9-transduced and parental C1498 cells (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data indicate that Mult1 downregulation by MARCH9 is reduced following heat shock, but MARCH9-mediated downregulation of other proteins, such as Db, is not. The results suggest that heat shock-dependent regulation targets Mult1 rather than targeting the MARCH9 E3 ligase or other targets of MARCH9.

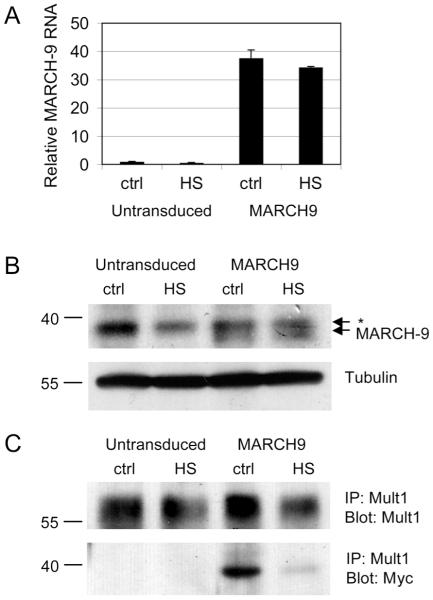

A dynamic association of Mult1 with MARCH9 underlies its regulation

The fact that Db is not induced by heat shock in mMARCH9-transduced cells suggested that a global change in MARCH9 activity might not be the cause of Mult1 regulation. To test this possibility, RNA and protein levels were analyzed before and after heat shock. As expected, transcript levels for mMARCH9 were higher in mMARCH9 transduced cells compared to parental C1498 cells, but there was not a significant reduction in transcript levels following heat shock (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the transduced mMARCH9 protein, detected by western blotting with Myc epitope antibodies, was not detectably depleted following heat shock (Fig. 5B). These data argue strongly against the possibility that heat shock stimulates Mult1 expression by reducing MARCH9 expression.

Figure 5. A dynamic association of Mult1 with MARCH9 underlies its regulation.

Cells treated as described in Figure 4 were used for MARCH9 quantitative PCR (A), myc western blot (B), or Mult1-MARCH9 co-IP (C). MARCH9 transcripts detected by QPCR were normalized to RPS29. The band in the Myc blot indicated by the * is a non-specific background band, below which myc-MARCH9 is visible. C-MARCH9 = C1498 cells transduced with mMARCH9, HS = heat shock, ctrl = untreated (no heat shock). Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

An alternative explanation for Mult1 regulation is that the interaction between Mult1 and MARCH9 is reduced or prevented following heat shock, thus preventing targeting of Mult1. To test this hypothesis, the extent of interaction between myc-tagged mMARCH9 and Mult1 was determined in lysates from C1498-MARCH9 cells, before or after heat shock. Similar amounts of Mult1 were detected in the immunoprecipitates, but the amount of mMARCH9 co-immunoprecipitated was substantially reduced (~5 fold) in heat shocked cells (Fig. 5C). This indicates that the association of mMARCH9 with Mult1 was indeed reduced following heat shock. The reduced interaction of Mult1 and mMARCH9 correlated with the increased display of Mult1 on the cell surface (Fig. 4C). These data are consistent with a dynamic Mult1-MARCH9 interaction and, since MARCH9 levels are not regulated by heat shock, suggest that a heat shock-sensitive event controls the extent of this interaction.

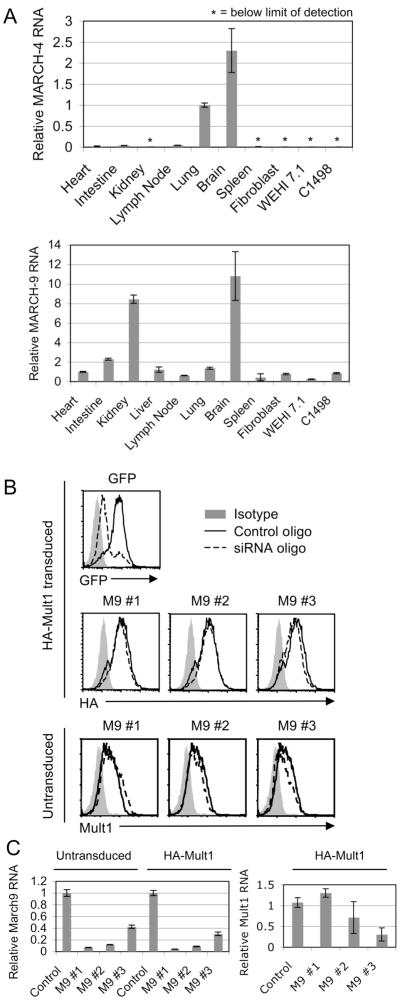

Analysis of endogenous MARCH9

While transduction of mMARCH4 and mMARCH9 clearly resulted in suppression of Mult1, it was important to investigate the role of the endogenous proteins. No antibodies against mouse MARCH4 or 9 are available, so analysis of endogenous expression was limited to transcript levels. To determine the tissue distribution of these MARCH family members, cDNA from a panel of mouse tissues and cells was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR for the presence of MARCH4 and MARCH9 transcripts (Fig. 6A). Transcripts for MARCH9 were represented in a broad range of tissues, but MARCH4 transcripts were more selectively expressed, most notably in the brain and lung. The tissue distribution observed here is similar to an already published analysis of human MARCH4/9 expression (9), suggesting similar roles for these proteins in mice and humans.

Figure 6. Analysis of endogenous MARCH9.

A. RNA from the indicated cells and tissues was used for MARCH4 or MARCH9 quantitative RT-PCR and relative quantity was determined by normalization to RPS29. An asterisk indicates that transcript amounts were below the limit of detection. B. Untransduced fibroblasts or fibroblasts expressing HA-tagged Mult1 were transfected with control oligos (solid line) or the indicated siRNA oligos (dashed line, M9=MARCH9). Expression of endogenous Mult1, GFP and HA-Mult1 was analyzed 72 hrs after transfection. C. RNA was extracted from the siRNA-transfected fibroblasts (B) for QPCR analysis, and relative levels of Mult1 and MARCH9 transcripts were determined by normalizing to RPS29. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

To more directly address the relative expression level of MARCH9 and MARCH4, PCR primers were designed that amplified a homologous region of these highly related transcripts, including a distinguishing SalI restriction enzyme site that is unique to MARCH4. SalI digestion of the PCR products was used to estimate the relative abundance of transcripts encoding MARCH4 (cleaved) versus MARCH9 (uncleaved). An established mouse fibroblast line (5) was selected for this more detailed analysis because this line had been well characterized in terms of Mult1 regulation. The PCR product from fibroblast cDNA was only visible as uncleaved product, indicating that MARCH9 is the only transcript present in appreciable quantities in these cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, MARCH9 could be specifically studied in these cells without the complication of appreciable co-expression MARCH4.

Mult1 in fibroblasts is maintained at low levels under normal conditions due to ubiquitination and degradation. To determine if the endogenous MARCH9 in these cells was responsible for low cell surface expression, siRNA oligos targeting MARCH9 were used to deplete MARCH9 transcripts. Untransduced fibroblasts or fibroblasts ectopically expressing WT Mult1 and GFP were transfected with GFP oligos, negative control oligos, or three different MARCH9 oligos. While the GFP oligos efficiently inhibited GFP expression in at least 80 percent of cells, demonstrating the high efficiency of transfection, none of the three different MARCH9 oligos used for knockdown resulted in appreciable increases in endogenous or ectopic Mult1 expression (Fig. 6B). Analysis of RNA levels in these cells showed that the MARCH9 oligos were effective, reducing transcript amounts by between 70 and 95 percent (Fig. 6C). Also, transfection of MARCH9 siRNA oligos into 3T3 cells ectopically expressing MARCH9 effectively restored Mult1 surface expression, further illustrating their effectiveness (Supplementary Fig. 2). To ensure that there were no off-target effects on Mult1, which could confound interpretation of the results, Mult1 transcripts were also quantified. While one of the oligos (M9 #3) appeared to reduce Mult1 RNA levels in this and some other experiments, the MARCH9 oligo that resulted in the best specific knockdown (M9 #1) had no effect on Mult1 transcript amounts (Fig. 6C). It is unlikely that endogenous MARCH4 was responsible for downregulating Mult1 in the absence of MARCH9, because these cells expressed vanishingly little MARCH4 mRNA (Fig. 6A). Moreover, no additional effect was observed when MARCH4 oligos were co-transfected with the MARCH9 oligos (unpublished observations). The results argue that MARCH9 and MARCH4 are not necessary for the basal suppression of Mult1 expression in these cells, but may carry out this function redundantly with another E3 ligase.

Discussion

The MARCH E3 ligases and their viral homologues are a recently described protein family. These proteins are distinguished from other RING-domain-containing E3 ligases by their unique configuration of cysteines and a histidine. Interestingly, they are all transmembrane proteins with as least two membrane-spanning segments, and most of their ubiquitination targets identified thus far have been transmembrane proteins. Of the MARCH-targeted proteins that have been identified, most are transmembrane molecules within the immune system. Our results demonstrate that ectopic expression of two members of this family, MARCH4 and MARCH9, prevent the expression of Mult1, adding this NKG2D ligand to the list of MARCH-regulated proteins. Our data support the notion that endogenous MARCH proteins, particularly the two-TM MARCH proteins, play numerous roles in regulation of immune functions, by regulating the cell surface display of proteins that activate immune responses.

MIR2, a homologue of the MARCH proteins encoded by KSHV, was recently shown to downregulate the human NKG2D ligands MICA and MICB (19). As it is believed that MIR2 originated as a human MARCH gene that was captured by KSHV, it is plausible that human MARCH proteins may also regulate NKG2D ligands. However, we failed to observe MICA or MICB downregulation in Jurkat cells transfected with any of the human two-TM MARCH cDNAs (unpublished data). Hence, MIR2 and endogenous hMARCH proteins may have diverged in their capacity to target MICA/B. It remains possible that MICA or MICB are regulated by one of the MARCH proteins not tested here or that MARCH proteins regulate a member of the distinct ULBP family of NKG2D ligands. Alternatively, Jurkat cells may be subject to constitutive stress signals that prevent targeting of MICA/B by transfected MARCH proteins.

The interaction of MARCH4 or 9 with Mult1 was specific in several respects. First, the other MARCH family members failed to appreciably downregulate Mult1 in the transfection experiments (Fig. 1A). Secondly, stable expression of mouse MARCH9 using retroviral transduction did not downregulate several other immunologically relevant cell surface proteins, including several potential MARCH targets such as ICAM-1, H60a, and Kb. In contrast, the class I molecule Db, another potential target, was downregulated, though not to the same extent as Mult1. These demonstrations of specificity argue against a non-specific effect of overexpression. In fact, the level of MARCH9 RNA in transduced C1498 cells (Fig. 5A) was only about five times higher than levels seen in tissues with the most abundant MARCH9 RNA (e.g. brain). Given the likely heterogeneity of expression in a tissue, the level of MARCH9 mRNA in individual cells in the tissue may be substantially higher. These considerations suggest that MARCH9 is not grossly overexpressed in C1498-MARCH9 cells.

Although ectopically expressed MARCH4/9 led to downregulation of Mult1 expression, MARCH4 and 9 are probably not the exclusive E3 ligases for Mult1, since knockdown of MARCH9 in fibroblasts that do not express detectable levels of MARCH4 transcript had no effect on Mult1 expression. The most likely explanation for this observation is redundancy of MARCH4/9 with as-of-yet unidentified cellular E3 ligases. These could be novel MARCH family members or non-MARCH E3 ligases. Notably, MARCH4/9 transcripts were more abundant in several tissues (e.g. brain, lung, and kidney, Fig. 6A) than in the cell lines analyzed, so MARCH4/9 may have a more prominent role in Mult1 regulation in the context of those tissues.

While expression of MARCH4 or MARCH9 in 293T cells and C1498 cells led to a strong downregulation of Mult1 from the cell surface, western blotting showed that they caused no (Fig. 1C, 4C) or a most a 2-fold reduction (unpublished data) in total Mult1 amounts in these cells. These observations suggest that Mult1 downregulation by MARCH4/9 was due largely to sequestration within the cell. MHC class II regulation by MARCH1/8 was also shown to be partially due to sequestration in intracellular compartments, though some degradation was also observed (17). In contrast, downregulation of Mult1 mediated by endogenous E3 ligases in fibroblasts resulted in very substantial reductions in total cellular Mult1 (7), suggesting that distinct E3 ligases prevent Mult1 cell surface expression by either degrading the protein or sequestering it in an intracellular compartment.

Interestingly, Mult1 was induced by heat shock both in fibroblasts, where down-regulation was not dependent on MARCH9 and in C1498-MARCH9 cells, where MARCH9 is the exclusive E3 ligase. In terms of the mechanism of heat shock regulation, these findings suggest that Mult1, rather than the E3 ligases, is targeted. This idea is supported by the observations that MARCH9 levels in C1498-MARCH9 cells did not change in response to heat shock (Fig. 5) and heat shock did not induce expression of the distinct MARCH9-targeted protein, Db (Fig. 4). A motif within the Mult1 cytoplasmic domain may be targeted by this stress response, in a manner that controls the interaction of Mult1 with its E3 ligases. Indeed, the Mult1 cytoplasmic tail is required for physical association with MARCH4/9, and so may also be important for the regulation of their interaction following heat shock. This interaction could be disrupted by the association of a regulatory molecule with the cytoplasmic tail that prevents E3 binding and/or ubiquitination or that targets Mult1 to a compartment inaccessible to the E3 ligase. Alternatively, heat shock may repress a regulator that facilitates E3 binding and/or ubiquitination of Mult1, but not other targets of MARCH4/9. Further analysis will be required to identify critical motifs within the cytoplasmic domain and how they regulate E3 ligase binding in response to heat shock.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Guerra N, Tan YX, Joncker NT, Choy A, Gallardo F, Xiong N, Knoblaugh S, Cado D, Greenberg NR, Raulet DH. NKG2D-deficient mice are defective in tumor surveillance in models of spontaneous malignancy. Immunity. 2008;28:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonjic S, Babic M, Polic B, Krmpotic A. Immune evasion of natural killer cells by viruses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogasawara K, Hamerman JA, Hsin H, Chikuma S, Bour-Jordan H, Chen T, Pertel T, Carnaud C, Bluestone JA, Lanier LL. Impairment of NK cell function by NKG2D modulation in NOD mice. Immunity. 2003;18:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raulet DH. Roles of the NKG2D immunoreceptor and its ligands. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:781–790. doi: 10.1038/nri1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, Raulet DH. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature. 2005;436:1186–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature03884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groh V, Bahram S, Bauer S, Herman A, Beauchamp M, Spies T. Cell stress-regulated human major histocompatibility complex class I gene expressed in gastrointestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12445–12450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nice TJ, Coscoy L, Raulet DH. Posttranslational regulation of the NKG2D ligand Mult1 in response to cell stress. J Exp Med. 2009;206:287–298. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartee E, Mansouri M, Hovey Nerenberg BT, Gouveia K, Fruh K. Downregulation of major histocompatibility complex class I by human ubiquitin ligases related to viral immune evasion proteins. J Virol. 2004;78:1109–1120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1109-1120.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohmura-Hoshino M, Goto E, Matsuki Y, Aoki M, Mito M, Uematsu M, Hotta H, Ishido S. A novel family of membrane-bound E3 ubiquitin ligases. J Biochem. 2006;140:147–154. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Gassart A, Camosseto V, Thibodeau J, Ceppi M, Catalan N, Pierre P, Gatti E. MHC class II stabilization at the surface of human dendritic cells is the result of maturation-dependent MARCH I down-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3491–3496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708874105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoer S, Smith L, Lehner PJ. MARCH-IX mediates ubiquitination and downregulation of ICAM-1. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehner PJ, Hoer S, Dodd R, Duncan LM. Downregulation of cell surface receptors by the K3 family of viral and cellular ubiquitin E3 ligases. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:112–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura N, Fukuda H, Kato A, Hirose S. MARCH-II is a syntaxin-6-binding protein involved in endosomal trafficking. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1696–1710. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hor S, Ziv T, Admon A, Lehner PJ. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture and differential plasma membrane proteome quantitation identify new substrates for the MARCH9 transmembrane E3 ligase. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1959–1971. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900174-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coscoy L, Sanchez DJ, Ganem D. A novel class of herpesvirus-encoded membrane-bound E3 ubiquitin ligases regulates endocytosis of proteins involved in immune recognition. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1265–1273. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin JS, Ebersold M, Pypaert M, Delamarre L, Hartley A, Mellman I. Surface expression of MHC class II in dendritic cells is controlled by regulated ubiquitination. Nature. 2006;444:115–118. doi: 10.1038/nature05261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez DJ, Coscoy L, Ganem D. Functional organization of MIR2, a novel viral regulator of selective endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6124–6130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas M, Boname JM, Field S, Nejentsev S, Salio M, Cerundolo V, Wills M, Lehner PJ. Down-regulation of NKG2D and NKp80 ligands by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K5 protects against NK cell cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1656–1661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707883105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamieson AM, Diefenbach A, McMahon CW, Xiong N, Carlyle JR, Raulet DH. The role of the NKG2D immunoreceptor in immune cell activation and natural killing. Immunity. 2002;17:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krmpotic A, Hasan M, Loewendorf A, Saulig T, Halenius A, Lenac T, Polic B, Bubic I, Kriegeskorte A, Pernjak-Pugel E, Messerle M, Hengel H, Busch DH, Koszinowski UH, Jonjic S. NK cell activation through the NKG2D ligand MULT-1 is selectively prevented by the glycoprotein encoded by mouse cytomegalovirus gene m145. J Exp Med. 2005;201:211–220. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranganath S, Ouyang W, Bhattarcharya D, Sha WC, Grupe A, Peltz G, Murphy KM. GATA-3-dependent enhancer activity in IL-4 gene regulation. J Immunol. 1998;161:3822–3826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cadwell K, Coscoy L. Ubiquitination on nonlysine residues by a viral E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2005;309:127–130. doi: 10.1126/science.1110340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Lybarger L, Connors R, Harris MR, Hansen TH. Model for the interaction of gammaherpesvirus 68 RING-CH finger protein mK3 with major histocompatibility complex class I and the peptide-loading complex. J Virol. 2004;78:8673–8686. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8673-8686.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.