Abstract

Adult stem cells maintain the mature tissues of metazoans. They do so by reproducing in such a way that their progeny either differentiate, and thus contribute functionally to a tissue, or remain uncommitted and replenish the stem cell pool. Because ageing manifests as a general decline in tissue function, diminished stem cell-mediated tissue maintenance may contribute to age-related pathologies. Accordingly, the mechanisms by which stem cell regenerative potential is sustained, and the extent to which these mechanisms fail with age, are fundamental determinants of tissue ageing. Here, we explore the mechanisms of asymmetric division that account for the sustained fitness of adult stem cells and the tissues that comprise them. In particular, we summarize the theory and experimental evidence underlying non-random chromosome segregation—a mitotic asymmetry arising from the unequal partitioning of chromosomes according to the age of their template DNA strands. Additionally, we consider the possible consequences of non-random chromosome segregation, especially as they relate to both replicative and chronological ageing in stem cells. While biased segregation of chromosomes may sustain stem cell replicative potential by compartmentalizing the errors derived from DNA synthesis, it might also contribute to the accrual of replication-independent DNA damage in stem cells and thus hasten chronological ageing.

Keywords: stem cells, cancer, ageing, DNA damage, asymmetric cell division

1. Introduction

Stem cells are essential contributors to tissue development and homeostasis. They not only give rise to diverse cell types during development, but also remain in mature tissues as adult stem cells. In mature organisms, stem cells are responsible for both homeostatic maintenance and repair in response to injury of tissues throughout the body. Accordingly, age-related declines in stem cell functions are intimately related to tissue ageing [1]. Fundamental to adult stem cell function is the dual role of generating the various cells that comprise mature tissue while self-replicating to sustain the stem cell population. Stem cells achieve this divergence of fate through asymmetric cell division—the generation of two distinctly destined daughter cells from a single mother cell [2]. One daughter adopts the fate of its mother, reflecting stem cell self-renewal; the other adopts a more committed fate, beginning a programme of differentiation unique to the specific tissue. Asymmetric cell division maintains a critical balance, preventing both the overproliferation of undifferentiated cells associated with oncogenesis and the depletion of the stem cell pool by differentiation [3].

From studies in a number of model systems, two distinct mechanisms of asymmetric cell division have emerged. First, the fate of a daughter cell may be intrinsically programmed by the asymmetric localization of fate determinants in the mother cell [2]. Such asymmetric cell divisions are associated with asymmetric segregation of proteins and transcripts to the two poles during mitosis, resulting in unequal partitioning of these fate determinants among daughter cells. Alternatively, fate may be extrinsically dictated by orientation of the division plane such that only one daughter receives appropriate cues from its contact with the stem cell niche [4]. Accumulating evidence from studies of stem cells in various tissues has confirmed a broader definition of mitotic asymmetry that includes an asymmetry at the level of DNA, namely the non-random segregation of sister chromosomes (reviewed in [5–7]).

(a). Non-random chromosome segregation: theory and phenomenology

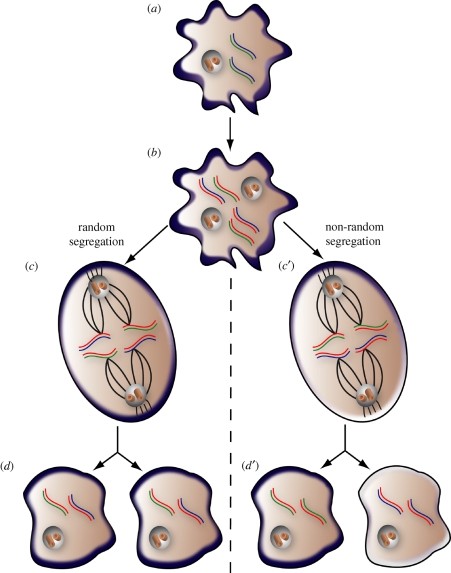

The non-random segregation is based on differences in the ages of the template strands of chromosomes distributed to two daughters: chromosomes bearing ‘younger’ templates are inherited by one daughter and chromosomes bearing ‘older’ templates are inherited by the other daughter (figure 1). Semi-conservative DNA replication dictates that, during S-phase, the two strands of a chromosome unwind, with each serving as the template for synthesis of a complementary strand [8]. However, the two strands of the original chromosome can be differentiated on the basis of their relative age: every chromosome consists of one strand that served as the template for the synthesis of the other during the preceding round of DNA replication. As such, one strand was ‘born’ (i.e. newly synthesized) one generation earlier, whereas the other was born at least two, and possibly many, generations earlier. Therefore, all chromosomes consist of complementary strands of different ages, each of which becomes a template during the next round of DNA synthesis. Consequently, the sister chromatids that segregate to daughter cells during mitosis can be differentiated on the basis of template strand age. Indeed, earlier studies describe asymmetric cell divisions during which just such template strand co-segregation (TSC) occurs (reviewed in [6]). However, the mechanisms that could mediate TSC according to template strand age and any potential advantage from an evolutionary perspective remain topics of debate [5–7,9,10].

Figure 1.

Non-random chromosome segregation and asymmetric cell fate determination. (a) Chromosomes in G1-phase consist of one older (blue) and one newer (green) strand. The difference in age between strands arises from semi-conservative DNA replication; that is, the older strand served as the template for synthesis of the newer strand during the preceding S-phase (not shown). Cells in G1 also contain a single centrosome composed of a mother and daughter centriole pair, surrounded by pericentriolar material. A membrane-associated cell fate determinant (i.e. Numb; dark blue) is diffusely localized during G1. (b) During S-phase, both strands of the chromosome serve as templates for synthesis of a nascent strand (red). Thus, sister chromosomes contain equivalently aged nascent strands, but differentially aged template strands. The centrosome also duplicates during S-phase. Both centrioles of the G1 centrosome give rise to a daughter centriole. Consequently, like chromosomes, centrosomes undergo semi-conservative replication and can be differentiated on the basis of the relative age of the mother centriole (not distinguished in this diagram). (c,d) Random chromosome segregation. (c) During metaphase, the mitotic spindle, originating from polarized centrosomes, is attached to chromosomes at the centromere. Each half-spindle makes attachments to one of the two sister chromatids, ensuring that both daughter cells inherit a single copy of each chromosome. If chromosomes segregate randomly, the half-spindle attaches to sister chromatids without regard for template strand age. According to the ISH, random chromosome segregation coincides with adoption of symmetric cell fates. Therefore, the cell fate determinant is distributed uniformly around the cell cortex during mitosis. (d) Following random chromosome segregation and cytokinesis, distinct daughter cells form. Each daughter inherits some chromosomes bearing older template strands (blue) and some chromosomes bearing newer template strands (green). Random chromosome segregation is a characteristic of symmetric cell division, depicted as symmetric inheritance of the cortical fate determinant (light blue). (c′,d′) Non-random chromosome segregation. (c′) If chromosomes segregate non-randomly, one half-spindle selectively attaches to sister chromatids bearing older template strands, while the other half-spindle attaches to sister chromatids bearing newer template strands. The ISH predicts that TSC correlates with asymmetric cell division. Accordingly, the membrane-associated fate determinant redistributes to one pole during mitosis. (d′) Following non-random chromosome segregation and cytokinesis, one daughter contains exclusively chromosomes bearing older template strands, while its sister contains only chromosomes bearing newer template strands. In agreement with the ISH, cells exhibiting TSC also adopt divergent fates, indicated by unequal partitioning of the cortical fate determinant. The ISH suggests that a fate determinant co-segregating with newer template strands (as depicted) will specify cell commitment. Alternatively, a segregating determinant that specifies stem cell self-renewal would be expected to segregate with the chromosomes bearing the older template strands (not shown).

In 1975, John Cairns proposed that TSC serves to limit the accumulation of replication-associated DNA damage in long-lived, mitotic cells (i.e. stem cells) [11]. Cairns' hypothesis, commonly referred to as the immortal strand hypothesis (ISH), holds that when a stem cell divides asymmetrically, the chromosomes bearing the older template DNA strands segregate to the self-renewing stem cell. Cairns postulated that, of the two template strands, that which was synthesized during the previous mitosis would have accumulated mutations owing to errors during replication. Consequently, he hypothesized that the chromosomes bearing the newer template DNA strands (containing unrepaired replication errors) would be inherited by the daughter cell that is destined to undergo differentiation. In this way, stem cells would retain a pristine copy of each chromosome—the so-called immortal strand—dating back to the developmental birth of the stem cell. Mutations in the DNA sequence arising during DNA replication would thereby be sequentially displaced from the stem cell compartment as they segregate to a differentiating daughter cell. Long-lived stem cells with extended replicative lifespans would thus avoid the accumulation of replication-induced DNA mutations.

Since Cairns proposed the ISH, studies in various cell types have offered experimental evidence of TSC. In general, these studies differentiate template DNA strand age by pulse-labelling with a radioactive or halogenated nucleotide (e.g. 3H-thymidine or BrdU, respectively). During a subsequent chase, segregation of labelled nucleotides can be followed through consecutive mitoses. If labelled nucleotides are pulsed early in the developmental lifetime of a cell or during a period of random chromosome segregation, the older (i.e. immortal) template strand may be labelled. Conversely, if the labelled nucleotides are pulsed later in a cell's lifetime, during a period of non-random chromosome segregation, only the newer template strands will be labelled. Using these approaches, TSC was first observed in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and plant root tips [12,13], where the pattern of segregation of newly synthesized template strands, labelled by a radioactive nucleotide, seemed non-random. Soon thereafter, TSC was seen in the germinating spores of the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans [14]. TSC has since been observed in intestinal epithelial cells [15,16], neural stem cells [17], mammary gland epithelial cells [18] and skeletal muscle stem cells of adult mice [19,20]. Recently, TSC was seen in germline stem cells of the Drosophila ovary [21]. It is important to note, however, that TSC has never been directly observed, owing to the technical challenges of imaging fluorescently tagged nucleotides or nucleotide analogues in living cells.

Evidence for TSC has been sought unsuccessfully in various other cell types. Shortly after Lark's initial discovery, investigators were unable to detect evidence of TSC in peripheral blood cells of the swamp wallaby (Wallabia bicolor) [22], plant meristematic cells [23], cultured Indian deer (Muntiacus muntjak) fibroblasts [24] and developing chick retinal cells [25]. Likewise, only random chromosome segregation has been characterized in the developing Caenorhabditis elegans embryo [26] and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [27]. More recently, it was suggested that label retention and TSC do not occur in haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [28]. Although the existence of slowly cycling, label-retaining HSCs has since been demonstrated [29,30], direct observation of TSC is still lacking. Other studies have found no evidence for TSC in mouse embryonic neocortical cells [31] and epidermal stem cells [32,33]. A comprehensive evaluation of both positive and negative evidence of TSC is challenging because of the diversity of experimental approaches, owing in part to the variety of cell types being studied. Among the numerous experimental intricacies possibly affecting TSC, the timing of the pulse-chase and the cellular context both in vivo and in culture is likely to play a role. Without insight into mechanism, it is difficult to determine to what extent experimental approaches might influence TSC.

The ISH predicts not only that TSC occurs, but also that it is a property of stem cells undergoing asymmetric cell division [11]. In particular, the ISH suggests that the chromosomes containing older template DNA strands should segregate preferentially to daughter cells that replenish the stem cell pool. Does evidence of TSC agree with the predictions of the ISH? Importantly, much of the aforementioned evidence of TSC comes from studies of stem or progenitor cells. Intriguingly, some of these cells exhibit increasingly random chromosome segregation with increasing passage in culture [13,19]. A number of studies have investigated asymmetric cell fate in populations exhibiting TSC. Some of the earliest studies of TSC in the intestinal epithelium indicated that newer template strands segregated away from the stem cell region of the intestinal crypt [15]. In skeletal muscle stem cells, TSC correlates with asymmetric localization of the cell fate determinant Numb [20]. Studies of skeletal muscle progenitor cells also reveal that markers of differentiation or stem cell self-renewal localize predominantly to the cell, inheriting newer or older template strands, respectively [19]. Similarly, in neural precursor cells, chromosomes carrying the older template strands segregate to cells expressing the neural stem cell markers Nestin and glial fibrillary acidic protein [17]. Taken together, studies of asymmetric fate determination in cells exhibiting TSC offer support for the ISH, although they do not limit TSC to stem cells since various progenitors also seem to retain this characteristic.

2. Functional consequences of template strand co-segregation

To date, no studies have examined whether, as Cairns hypothesized, chromosomes are segregated based upon, or associated with, the differential burden of DNA mutations on the template strands, or whether the process has any relevance to the later development of cancer. Although such studies are lacking, other work points indirectly to the significance of TSC. As mentioned above, TSC in skeletal muscle progenitor cells appears to coincide with asymmetric segregation of the cell fate determinant Numb [20]. Studies of the functional role of Numb both developmentally and postnatally have generally been related to its ability to inhibit Notch signalling [34,35]. However, recent studies have revealed an additional tumour-suppressor function of Numb [36]. Specifically, Numb interacts with and inhibits the E3 ubiquitin ligase HDM2 (MDM2), thus preventing the ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Decreased Numb expression delays the repair of double-strand breaks introduced by a chemical mutagen. Why does an asymmetrically segregated fate determinant function as a tumour suppressor and regulator of the DNA damage response? The asymmetric localization of Numb could lead to the stabilization of p53 exclusively in one daughter cell. Given that asymmetric Numb segregation coincides with TSC, Numb may be segregating to the daughter cell that inherits the newer, error-ridden template strands. The effect of non-random Numb inheritance might be to enforce a programme of cell-cycle arrest and DNA repair in one of two daughters. Remarkably, because of its dual functions, Numb seems capable of driving both differentiation and DNA repair in certain progenitor cell populations. Thus, Numb provides a molecular link between TSC, DNA damage inheritance and asymmetric cell fate determination. Viewed in this light, Numb loss-of-function studies in cell populations known to exhibit TSC should provide insights into the functional significance of TSC itself.

Cairns initially proposed the ISH as a means of decreasing the likelihood of cellular pathologies associated with increased replicative age, specifically cancer. Still, there is no evidence that TSC is a mechanism for preventing cancer. Indeed, a clear indication that TSC suppresses cancer would require genetic manipulations that specifically increase random chromosome segregation without otherwise affecting chromosome alignment and segregation. The only hint that TSC has a role in the development or progression of cancer comes from a recent study by Quyn et al. [37], which shows that TSC in gut epithelium is lost in mice heterozygous for a loss-of-function allele of the tumour suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli (APC). The mutant mice go on to develop intestinal polyps and cancers, mimicking human familial adenomatous polyposis. Striking as these data may be, the cellular effects of loss of APC, such as activation of canonical Wnt signalling [38], are too wide-ranging to link the cancer phenotype to loss of TSC. Moreover, there is no evidence to suggest a role for APC in the mechanism of TSC. Additional studies are required to determine how APC might affect TSC and whether the tumour phenotype in mice heterozygous for APC is specifically related to loss of TSC.

Might TSC function in the cell other than as a general tumour-suppressor mechanism? Others have suggested that TSC is a mechanism for conferring divergent epigenetic identities to daughter cells [7,39,40]. This model holds that template strands bear epigenetic information that can contribute to asymmetric fate determination. A key characteristic of this type of TSC is that chromosomes segregate according to template strand sequence (i.e. Watson or Crick), rather than template strand age. Non-random segregation of mouse chromosome 7 was observed in mouse embryonic stem cells and tissue-specific precursor cells [39]. In a recent study that employed chromosome orientation fluorescence in situ hybridization to identify template strand sequence, TSC was observed in the intestinal epithelium, but not cultured lung fibroblasts or embryonic stem cells [40]. Using DNA sequences at the centromere to identify Watson and Crick strands in intestinal epithelial cells, the authors reported that template strands with similar centromeric sequences segregate together more often than predicted by random segregation. It is important to note that the two means of differentiating sister chromosomes (i.e. by centromeric sequence or relative age of template strands) are not mutually exclusive. Many questions remain concerning the template sequence model of TSC. Our current understanding of epigenetic inheritance during DNA replication and subsequent mitosis does not provide a framework for explaining how sister chromatids could diverge epigenetically. Also, unequivocal evidence of asymmetric epigenetic inheritance would require characterization of the epigenetic state of sister cells. Current techniques for epigenetic analysis must be enhanced to make such a study possible.

3. Maintenance of stem cell lineages by non-random segregation of dna damage

Whether stem cells age and to what degree the ageing of stem cells contributes to the overall decline of tissue function in aged organisms are unsettled questions [1]. The issue is further clouded by evidence that functional attributes of aged stem cells reflect not only cell-intrinsic changes, but also age-related alteration of the local and systemic niche [41–43]. Indeed, the ageing-associated dysfunction of certain adult stem cells can be partially reversed simply by exposing these cells to a young systemic environment [44]. Whether stem cell ageing is viewed as cell-autonomous or cell non-autonomous, the ISH offers a mechanism whereby stem cells might be protected from a key source of replicative ageing—DNA damage arising from copying the genome. Thus, TSC, especially as formulated in the ISH, has clear implications for ageing within stem cell lineages and the tissues that they generate.

Ageing has long been linked to the accumulation of DNA damage [45]. Much of the experimental evidence supporting this association comes from studies of transgenic organisms that are deficient in certain DNA-repair proteins [46]. These organisms display a variety of abnormalities, many of which have features suggestive of premature ageing. Interestingly, the decline of cellular function in the setting of DNA damage is not always due to DNA damage per se, but often stems from the cellular response to this damage (i.e. senescence or apoptosis) [47]. Accordingly, a number of transgenic organisms carrying hypermorphic alleles of DNA damage response proteins exhibit age-related phenotypes analogous to those observed in repair-deficient organisms [48,49].

Recently, DNA damage has been related to the impaired function of tissue-specific stem cells with age. In mice bearing germline mutations in proteins critical for non-homologous end joining or nucleotide excision repair, HSCs exhibit a significant decline in regenerative capacity as they grow older [50]. Furthermore, hair-greying in mice exposed to ionizing radiation has been correlated with DNA damage in melanocyte stem cells [51]. These cells respond to DNA damage by prematurely differentiating into melanocytes, ultimately leading to a decline in pigment production in the hair follicle. In mice deficient in ataxia–telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) protein, which orchestrates DNA damage repair pathways, melanocyte stem cells are sensitized to the effects of ionizing radiation.

Drawing the connection between DNA damage and stem cell function during healthy (i.e. non-pathological) ageing has proved difficult. Many mammalian tissues show accrual of markers of DNA damage with age [52]. Such markers even accumulate in highly purified HSCs [50] and quiescent skeletal muscle satellite cells (G. W. Charville & T. A. Rando 2010, unpublished data) from aged mice. Although there is extensive evidence that DNA damage can limit the function of stem cells, the extent to which accrual of unrepaired DNA damage explains the impaired regenerative capacity of healthfully aged tissues remains unclear.

Among the sources of DNA damage under normal physiological conditions [53], the stress of DNA replication is particularly relevant to ageing and the ISH in particular. DNA is damaged during replication, and this damage may manifest as a finite cellular replicative lifespan [54]. One might then hypothesize that simply increasing the replicative burden of stem cells should hasten their functional decline. One way to address this question is to ablate a sizable portion of the stem cell pool early in adulthood, thereby shifting the demands of tissue regeneration to a few surviving cells [55]. Such an experiment was recently performed by conditionally deleting ATM- and Rad3-related protein (ATR) in adult mice [56]. ATR is a DNA damage response protein that is absolutely required for the survival of proliferating cells [57]. Therefore, conditional deletion of ATR in adult mice leads to rapid death of mitotic cells in which the transgene has been successfully recombined. Upon deletion of ATR, mice exhibit atrophy of high-turnover tissues such as blood and intestine. However, most mice survive the loss of ATR. In these mice, rare progenitor cells that failed to recombine the transgene expand and replace the dying mutant cells. One month after deletion of ATR, the mice return to normal. Just a few months thereafter, the mice exhibit a profound progeroid-like syndrome affecting bone, blood and skin, among other tissues. This secondary loss of regenerative capacity is consistent with a model in which wild-type progenitor cells respond to a primary loss of their mutant counterparts by proliferative expansion [47,55]. The strain of increased proliferation eventually leads to failure of wild-type cells, demonstrating that replication stress can cause stem cell dysfunction and may relate to normal stem cell ageing. This interpretation is in agreement with the earlier observation that serial transplantation of HSCs leads to a substantial loss of their regenerative capacity [58].

If the accumulation of replication-associated DNA damage leads to stem cell dysfunction (cancer or senescence), asymmetric segregation of this damage may be a means of sustaining stem cell fitness. Intriguingly, the asymmetric localization of damaged proteins has been studied in the S. cerevisiae model of replicative ageing. Saccharomyces cerevisiae undergo a morphologically asymmetric division in which a daughter cell buds from its mother [59]. By observing individual cells through numerous rounds of budding, it was found that replicative lifespan—the number of times that a particular cell can bud before it stops reproducing and dies—is finite [60]. In addition, chronicling the life history of individual cells and their progeny has indicated that mother cells, to an extent, do not convey their replicative age to their daughters, as indeed must be the case in order to propagate the species [60,61]. It has been hypothesized that mother cells ‘age’ by the accumulation of damaged or misfolded proteins, ultimately leading to senescence [62,63]. During the budding process, such damaged proteins selectively segregate to the mother cell, apparently by transport of any damaged proteins from the daughter back to the mother, thus rendering the new daughter ‘youthful’ by this measure [64]. This mechanism of ageing in yeast and other unicellular organisms [65] has led some to posit that asymmetric segregation of damage has evolved to restrict senescence to individual branches of a cell lineage [66].

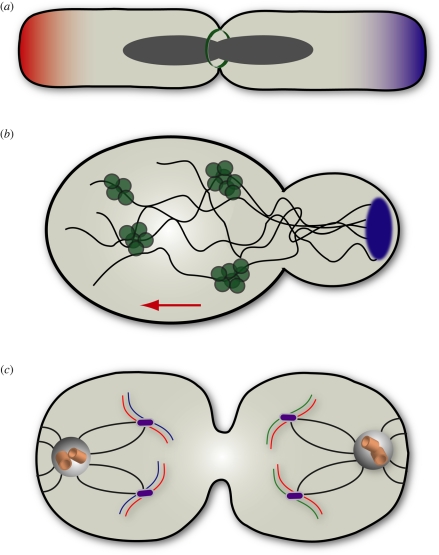

Is non-random chromosome segregation another mechanism of lineage maintenance by damage segregation? Like damaged proteins, damaged DNA can initiate terminal cell fates such as senescence or apoptosis. Thus, progenitor cells inheriting damaged DNA may die or endure temporary or permanent cell-cycle arrest. In either case, the replicative potential of progenitor cells is compromised. If, however, damaged DNA is segregated exclusively to the differentiating daughter cell arising from an asymmetric division, the self-renewing progenitor can continue to function in cycles of quiescence, activation, asymmetric cell division and self-renewal. Remarkably, the unequal partitioning of damaged macromolecules seems to be a conserved strategy for maintaining reproductive fitness within a cell lineage (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lineage preservation by non-random segregation of damaged cell components. (a) During binary fission in Escherichia coli, two new poles are formed at the site of cytokinesis (green). Each of the progeny cells inherits one copy of the circular genome (grey) and one new pole. Thus, individual E. coli cells have one newer and one older pole. By following individual cells through successive divisions, it has been shown that the cell inheriting the older pole (red) exhibits decreased reproductive capacity and increased likelihood of cell death relative to its sister cell, which inherits the newer pole (blue) [65]. The decreased fitness associated with the old pole might relate to passive accumulation of aged cellular components that permanently dwell at the pole, or active partitioning of dysfunctional components to the older pole. (b) When S. cerevisiae reproduce, a smaller daughter cell (right) buds from its mother (left). This morphologically asymmetric division is characterized by non-random segregation of oxidatively damaged or misfolded proteins (green). Dysfunctional proteins are transported retrogradely (red arrow) as aggregates into the mother cell prior to the completion of budding [64]. The polarisome (blue) orchestrates the transport of damaged proteins during mitosis via an actin network (dark grey). Analogous to the bacterium inheriting the older pole, the yeast mother cell, which retains damaged proteins, exhibits decreased replicative potential and shortened lifespan relative to its daughter. (c) Certain examples of mammalian mitosis, namely asymmetric divisions of adult stem cells, exhibit non-random segregation of chromosomes by template strand age. TSC occurs when the full complement of chromosomes bearing older template strands (blue) segregate to one of two daughter cells. The effect of TSC, according to the ISH, may be to sequester DNA damage arising from DNA synthesis in the daughter cell (right) inheriting the newer template strands (green). The damage initially present in newly synthesized strands (red) must be equally segregated to both daughters. Like the phenomena depicted in (a) and (b), TSC may function to preserve the fitness of a cell lineage by restricting damage to one daughter—the daughter that is destined to differentiate. Notably, the obvious involvement of the mitotic spindle apparatus in selective segregation of sister chromosomes implies functional, possibly age-related, differences in the kinetochores (purple) and centrosomes.

Asymmetric segregation of DNA damage according to the ISH seems to present a paradox: if newly synthesized DNA contains damage and chromosomes are replicated semi-conservatively, then sister chromosomes will contain symmetric damage in the nascent strands. This suggests that DNA damage on the template strands, where an asymmetry between sister chromosomes is expected, may have special significance for the relative fitness of the daughters of stem cell division. According to the ISH, but perhaps contrary to intuition, it is the older template strand that is fitter, lacking the damage derived from errors generated during DNA synthesis. In other words, the newer template strand will reflect DNA damage arising in the previous S-phase and may convey a lack of fitness to the daughter cell that inherits it.

While new DNA bears the scars of replication-associated damage, older DNA remains susceptible to accumulation of chemical modifications and decompositions with chronological age. Such lesions may result from environmental mutagens or the by-products of cellular metabolism, which, in contrast to replication-associated damage, presumably display no bias for particular strands. Therefore, as organisms age, the relative fitness of old DNA strands may diminish. This mechanism of chronological ageing could be particularly important in cells that have continually inherited an immortal DNA strand for an extended period: one would expect long-lived strands to have collected more lesions, or ‘age spots’, if the repair of those lesions is incomplete [67]. Even if TSC is a response to differential damage on template DNA strands, the accumulation of lesions on old strands might lead to a decline in TSC and a subsequent loss of stem cell regenerative potential.

4. Summary

Two mechanisms of damage accumulation may contribute to ageing in adult stem cell lineages. On one hand, mutations arising from DNA synthesis can be a source of replicative ageing. As discussed herein, TSC may abrogate the effects of replication-associated damage by preferentially sequestering the newly synthesized strands bearing this damage away from the self-renewing stem cell. On the other hand, replication-independent damage may increase with chronological age, especially in long-lived (i.e. immortal) DNA strands. We conclude that TSC, which maintains progenitor cell fitness and tolerance to replicative ageing in the short term, could in theory increase stem cell susceptibility to chronological ageing.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the NIH (F30 AG35521) and the Stanford Medical Scientist Training Programme to G.W.C., and from the American Federation for Aging Research and the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research (‘Breakthrough in Gerontology’ Award) and the NIH (R01 AG23806 and NIH Director's Pioneer Award DP1 OD000392) to T.A.R.

Footnotes

One contribution of 15 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘The new science of ageing’.

References

- 1.Rando T. A.2006Stem cells, ageing and the quest for immortality. Nature 441, 1080–1086 10.1038/nature04958 (doi:10.1038/nature04958) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knoblich J. A.2008Mechanisms of asymmetric stem cell division. Cell 132, 583–597 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.007 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison S. J., Kimble J.2006Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature 441, 1068–1074 10.1038/nature04956 (doi:10.1038/nature04956) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuller M. T., Spradling A. C.2007Male and female Drosophila germline stem cells: two versions of immortality. Science 316, 402–404 10.1126/science.1140861 (doi:10.1126/science.1140861) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairns J.2006Cancer and the immortal strand hypothesis. Genetics 174, 1069–1072 10.1534/genetics.104.66886 (doi:10.1534/genetics.104.66886) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rando T. A.2007The immortal strand hypothesis: segregation and reconstruction. Cell 129, 1239–1243 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.019 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tajbakhsh S.2008Stem cell identity and template DNA strand segregation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 716–722 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030045 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meselson M., Stahl F. W.1958The replication of DNA in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 44, 671–682 10.1073/pnas.44.7.671 (doi:10.1073/pnas.44.7.671) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lansdorp P. M.2007Immortal strands? Give me a break. Cell 129, 1244–1247 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.017 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lew D. J., Burke D. J., Dutta A.2008The immortal strand hypothesis: how could it work? Cell 133, 21–23 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.016 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cairns J.1975Mutation selection and the natural history of cancer. Nature 255, 197–200 10.1038/255197a0 (doi:10.1038/255197a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lark K. G.1967Nonrandom segregation of sister chromatids in Vicia faba and Triticum boeoticum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 58, 352–359 10.1073/pnas.58.1.352 (doi:10.1073/pnas.58.1.352) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lark K. G., Consigli R. A., Minocha H. C.1966Segregation of sister chromatids in mammalian cells. Science 154, 1202–1205 10.1126/science.154.3753.1202 (doi:10.1126/science.154.3753.1202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberger R. F., Kessel M.1968Nonrandom sister chromatid segregation and nuclear migration in hyphae of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 96, 1208–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potten C. S., Hume W. J., Reid P., Cairns J.1978The segregation of DNA in epithelial stem cells. Cell 15, 899–906 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90274-X (doi:10.1016/0092-8674(78)90274-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potten C. S., Owen G., Booth D.2002Intestinal stem cells protect their genome by selective segregation of template DNA strands. J. Cell. Sci. 115, 2381–2388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karpowicz P., Morshead C., Kam A., Jervis E., Ramunas J., Ramuns J., Cheng V., van der Kooy D.2005Support for the immortal strand hypothesis: neural stem cells partition DNA asymmetrically in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 170, 721–732 10.1083/jcb.200502073 (doi:10.1083/jcb.200502073) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith G. H.2005Label-retaining epithelial cells in mouse mammary gland divide asymmetrically and retain their template DNA strands. Development 132, 681–687 10.1242/dev.01609 (doi:10.1242/dev.01609) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conboy M. J., Karasov A. O., Rando T. A.2007High incidence of non-random template strand segregation and asymmetric fate determination in dividing stem cells and their progeny. PLoS Biol. 5, e102. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050102 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinin V., Gayraud-Morel B., Gomès D., Tajbakhsh S.2006Asymmetric division and cosegregation of template DNA strands in adult muscle satellite cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 677–687 10.1038/ncb1425 (doi:10.1038/ncb1425) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karpowicz P., Pellikka M., Chea E., Godt D., Tepass U., van der Kooy D.2009The germline stem cells of Drosophila melanogaster partition DNA non-randomly. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 88, 397–408 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.03.001 (doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.03.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geard C. R.1973Chromatid distribution at mitosis in cultured Wallabia bicolor cells. Chromosoma 44, 301–308 10.1007/BF00291024 (doi:10.1007/BF00291024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernández-Gómez M., De al Torre C., Stockert J.1975Random segregation of sister chromatids in meristematic cells. Exp. Cell Res. 96, 156–160 10.1016/S0014-4827(75)80048-6 (doi:10.1016/S0014-4827(75)80048-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayron R., Wise D.1976Random distribution of centromere regions at mitosis in cultured cells of Muntiacus muntjak. Chromosoma 55, 69–74 10.1007/BF00288328 (doi:10.1007/BF00288328) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris V. B.1977Random segregation of sister chromatids in developing chick retinal cells demonstrated in vivo using the fluorescence plus Giemsa technique. Chromosoma 60, 139–145 10.1007/BF00288461 (doi:10.1007/BF00288461) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito K., McGhee J. D.1987Parental DNA strands segregate randomly during embryonic development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell 49, 329–336 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90285-6 (doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90285-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neff M. W., Burke D. J.1991Random segregation of chromatids at mitosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 127, 463–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiel M. J., He S., Ashkenazi R., Gentry S. N., Teta M., Kushner J. A., Jackson T. L., Morrison S. J.2007Haematopoietic stem cells do not asymmetrically segregate chromosomes or retain BrdU. Nature 449, 238–242 10.1038/nature06115 (doi:10.1038/nature06115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foudi A., Hochedlinger K., Van Buren D., Schindler J. W., Jaenisch R., Carey V., Hock H.2009Analysis of histone 2B-GFP retention reveals slowly cycling hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 84–90 10.1038/nbt.1517 (doi:10.1038/nbt.1517) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson A., et al. 2008Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell 135, 1118–1129 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fei J., Huttner W. B.2009Nonselective sister chromatid segregation in mouse embryonic neocortical precursor cells. Cereb. Cortex 19(Suppl. 1), i49–i54 10.1093/cercor/bhp043 (doi:10.1093/cercor/bhp043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuroki T., Murakami Y.1989Random segregation of DNA strands in epidermal basal cells. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 80, 637–642 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1989.tb01690.x (doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.1989.tb01690.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sotiropoulou P. A., Candi A., Blanpain C.2008The majority of multipotent epidermal stem cells do not protect their genome by asymmetrical chromosome segregation. Stem Cells 26, 2964–2973 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0634 (doi:10.1634/stemcells.2008-0634) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frise E., Knoblich J. A., Younger-Shepherd S., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N.1996The Drosophila Numb protein inhibits signaling of the Notch receptor during cell–cell interaction in sensory organ lineage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 11 925–11 932 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11925 (doi:10.1073/pnas.93.21.11925) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gulino A., Di Marcotullio L., Screpanti I.2010The multiple functions of Numb. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 900–906 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.11.017 (doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.11.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colaluca I. N., Tosoni D., Nuciforo P., Senic-Matuglia F., Galimberti V., Viale G., Pece S., Di Fiore P. P.2008NUMB controls p53 tumour suppressor activity. Nature 451, 76–80 10.1038/nature06412 (doi:10.1038/nature06412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quyn A. J., Appleton P. L., Carey F. A., Steele R. J. C., Barker N., Clevers H., Ridgway R. A., Sansom O. J., Näthke I. S.2010Spindle orientation bias in gut epithelial stem cell compartments is lost in precancerous tissue. Cell Stem Cell 6, 175–181 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.007 (doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bienz M., Clevers H.2000Linking colorectal cancer to Wnt signaling. Cell 103, 311–320 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00122-7 (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00122-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armakolas A., Klar A. J. S.2006Cell type regulates selective segregation of mouse chromosome 7 DNA strands in mitosis. Science 311, 1146–1149 10.1126/science.1120519 (doi:10.1126/science.1120519) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falconer E., Chavez E. A., Henderson A., Poon S. S. S., McKinney S., Brown L., Huntsman D. G., Lansdorp P. M.2010Identification of sister chromatids by DNA template strand sequences. Nature 463, 93–97 10.1038/nature08644 (doi:10.1038/nature08644) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conboy I. M., Conboy M. J., Smythe G. M., Rando T. A.2003Notch-mediated restoration of regenerative potential to aged muscle. Science 302, 1575–1577 10.1126/science.1087573 (doi:10.1126/science.1087573) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brack A. S., Conboy M. J., Roy S., Lee M., Kuo C. J., Keller C., Rando T. A.2007Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science 317, 807–810 10.1126/science.1144090 (doi:10.1126/science.1144090) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gopinath S. D., Rando T. A.2008Stem cell review series: aging of the skeletal muscle stem cell niche. Aging Cell 7, 590–598 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00399.x (doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00399.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conboy I. M., Conboy M. J., Wagers A. J., Girma E. R., Weissman I. L., Rando T. A.2005Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature 433, 760–764 10.1038/nature03260 (doi:10.1038/nature03260) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirkwood T. B., Austad S. N.2000Why do we age? Nature 408, 233–238 10.1038/35041682 (doi:10.1038/35041682) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park Y., Gerson S. L.2005DNA repair defects in stem cell function and aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 56, 495–508 10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104546 (doi:10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104546) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharpless N. E., DePinho R. A.2007How stem cells age and why this makes us grow old. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 703–713 10.1038/nrm2241 (doi:10.1038/nrm2241) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morales M., Theunissen J. F., Kim C. F. B., Kitagawa R., Kastan M. B., Petrini J. H. J.2005The Rad50S allele promotes ATM-dependent DNA damage responses and suppresses ATM deficiency: implications for the Mre11 complex as a DNA damage sensor. Genes Dev. 19, 3043–3054 10.1101/gad.1373705 (doi:10.1101/gad.1373705) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tyner S. D., et al. 2002p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature 415, 45–53 10.1038/415045a (doi:10.1038/415045a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossi D. J., Bryder D., Seita J., Nussenzweig A., Hoeijmakers J., Weissman I. L.2007Deficiencies in DNA damage repair limit the function of haematopoietic stem cells with age. Nature 447, 725–729 10.1038/nature05862 (doi:10.1038/nature05862) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inomata K., et al. 2009Genotoxic stress abrogates renewal of melanocyte stem cells by triggering their differentiation. Cell 137, 1088–1099 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.037 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang C., Jurk D., Maddick M., Nelson G., Martin-Ruiz C., von Zglinicki T.2009DNA damage response and cellular senescence in tissues of aging mice. Aging Cell 8, 311–323 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00481.x (doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00481.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson D. M., III, Bohr V. A., McKinnon P. J.2008DNA damage, DNA repair, ageing and age-related disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 129, 349–352 10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.013 (doi:10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burhans W. C., Weinberger M.2007DNA replication stress, genome instability and aging. Nucl. Acids Res. 35, 7545–7556 10.1093/nar/gkm1059 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkm1059) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruzankina Y., Asare A., Brown E. J.2008Replicative stress, stem cells and aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 129, 460–466 10.1016/j.mad.2008.03.009 (doi:10.1016/j.mad.2008.03.009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruzankina Y., et al. 2007Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell 1, 113–126 10.1016/j.stem.2007.03.002 (doi:10.1016/j.stem.2007.03.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown E. J., Baltimore D.2000ATR disruption leads to chromosomal fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes Dev. 14, 397–402 10.1101/gad.14.4.397 (doi:10.1101/gad.14.4.397) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamminga L. M., Os R. V., Ausema A., Noach E. J. K., Weersing E., Dontje B., Vellenga E., Haan G. D.2005Impaired hematopoietic stem cell functioning after serial transplantation and during normal aging. Stem Cells 23, 82–92 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0066 (doi:10.1634/stemcells.2004-0066) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pruyne D., Legesse-Miller A., Gao L., Dong Y., Bretscher A.2004Mechanisms of polarized growth and organelle segregation in yeast. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 559–591 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.103108 (doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.103108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mortimer R. K., Johnston J. R.1959Life span of individual yeast cells. Nature 183, 1751–1752 10.1038/1831751a0 (doi:10.1038/1831751a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kennedy B. K., Austriaco N. R., Guarente L.1994Daughter cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae from old mothers display a reduced life span. J. Cell Biol. 127, 1985–1993 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1985 (doi:10.1083/jcb.127.6.1985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aguilaniu H., Gustafsson L., Rigoulet M., Nyström T.2003Asymmetric inheritance of oxidatively damaged proteins during cytokinesis. Science 299, 1751–1753 10.1126/science.1080418 (doi:10.1126/science.1080418) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Egilmez N. K., Jazwinski S. M.1989Evidence for the involvement of a cytoplasmic factor in the aging of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 171, 37–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu B., Larsson L., Caballero A., Hao X., Oling D., Grantham J., Nyström T.2010The polarisome is required for segregation and retrograde transport of protein aggregates. Cell 140, 257–267 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.031 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stewart E. J., Madden R., Paul G., Taddei F.2005Aging and death in an organism that reproduces by morphologically symmetric division. PLoS Biol. 3, e45. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030045 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030045) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kirkwood T. B.2005Asymmetry and the origins of ageing. Mech. Ageing Dev. 126, 533–534 10.1016/j.mad.2005.02.001 (doi:10.1016/j.mad.2005.02.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sherley J. L.2008A new mechanism for aging: chemical ‘age spots’ in immortal DNA strands in distributed stem cells. Breast Dis. 29, 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]