Abstract

Hunter–gatherer Pygmies from Central Africa are described as being extremely mobile. Using neutral genetic markers and population genetics theory, we explored the dispersal behaviour of the Baka Pygmies from Cameroon, one of the largest Pygmy populations in Central Africa. We found a strong correlation between genetic and geographical distances: a pattern of isolation by distance arising from limited parent–offspring dispersal. Our study suggests that mobile hunter–gatherers do not necessarily disperse over wide geographical areas.

Keywords: African Pygmies, dispersal, isolation by distance, microsatellites, population genetics

1. Introduction

The correlation between genetics and geography has been extensively studied at a worldwide scale to better characterize the distribution of human genetic diversity and estimate key parameters of modern humans' expansion worldwide (e.g. Ramachandran et al. 2005; Liu et al. 2006; DeGiorgio et al. 2009). However, none of these studies have characterized parent–offspring dispersal and therefore, the dispersal mechanisms underlying the geographical distribution of human genetic diversity remain unclear.

Ethnologists have shown the great variability of mobility across human populations with different lifestyles and modes of subsistence. For example, foragers have been shown to be much more mobile than farmers (MacDonald & Hewlett 1999). However, the relationship between mobility and effective dispersal (characterized by the distances between children's and parents' birthplaces) often remains unknown. To explore this aspect, we studied African Pygmies, which represent the largest hunter–gatherer group of populations worldwide. African Pygmies are described as being very mobile within the rainforest for seasonal mobility and socioeconomic activities (Bahuchet 1992). Demographic data in an Aka Pygmy population further showed large mating ranges and large distances between birthplaces and places of residence (Cavalli-Sforza & Hewlett 1982). This suggests that such mobile behaviour should translate into long distances between children's and parents' birthplaces, but this assumption has never been explicitly tested owing to limited demographic data (Cavalli-Sforza 1986). In this context, population genetics can provide indirect estimates of effective dispersal in these hunter–gatherers. Indeed, isolation by distance theory predicts that at equilibrium between drift, migration and mutation, the regression of F-statistics estimates on the logarithm of geographical distances provides a robust estimate of the neighbourhood size, which is proportional to the population density and the second moment of parent–offspring distance, if individuals are sampled at a short geographical scale (Rousset 1997).

Here, we report estimates of effective dispersal based on the relationship between genetic and geographical distances in three groups of the Baka Pygmies from Cameroon. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the only genetic data for such a small geographical scale in African Pygmy populations, which provides an opportunity to infer effective dispersal using the genetics of these mobile hunter–gatherers.

2. Material and methods

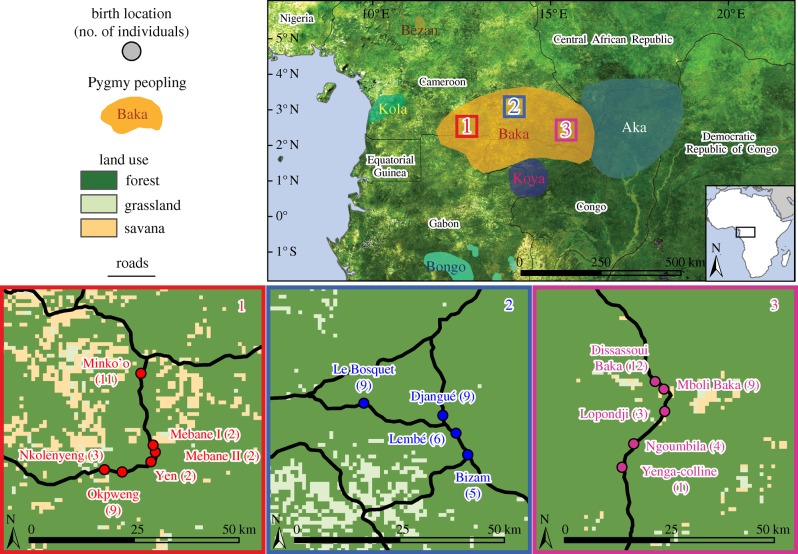

The Baka from Cameroon represent one of the largest Pygmy populations with 35 000 individuals occupying 75 000 km2 in the rainforest (figure 1). These values, which were compiled from ethnographic data (Vallois & Marquer 1976; Dhellemmes & Macaigne 1985; Cavalli-Sforza 1986; Sato 1992; Abéga 1998; Tsuru 2001), provide an estimate of the population density of D = 0.47 individuals · km−2.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of the 87 Baka Pygmies sampled in southeastern Cameroon. In each Baka group, birthplaces of sampled individuals are shown with sample sizes given in parentheses. Other Pygmy peopling areas inferred from our ethnographical fieldworks are shown. Map sources: Global Land Cover Facility.

We consider 87 Baka adults genotyped at 28 independent tetranucleotide microsatellite loci (Verdu et al. 2009). We visited Baka settlements along three transects of approximately 50 km each (figure 1), asking volunteers to gather for DNA sampling at a single location for each transect. Frequent movements between places of temporary residence, as well as hospitality rules among Pygmies that assimilate visitors as residents during their visit, make it difficult to determine whether an individual met in a village is a resident or a visitor (Cavalli-Sforza 1986; Bahuchet 1992). Therefore, the sampling location, or the location where individuals were first met, are probably a poor predictor of Pygmies' location after dispersal and these data were discarded. Instead, we considered that birthplaces provided more robust data to study Pygmies' dispersal. After collecting each individual's birthplace, we went back on the road to determine the geographical coordinates of these locations. Each donor provided appropriate informed oral consent.

Geographically limited dispersal across generations in two-dimensional habitats results in a linear relationship between pairwise genetic distances ar, an analogue to FST/(1 − FST) calculated between pairs of individuals (Rousset 2000), and the logarithm of geographical distance. We used the software package GenePop' 007 (Rousset 2008) to calculate the slope of this linear regression, which, at a small geographic scale, provides a robust estimator of 1/(4Dπσ2), where D is the effective population density and σ2 is the second moment of parent–offspring axial distance (Rousset 1997). We tested the significance of the correlation using a Mantel test (Mantel 1967) with 30 000 permutations. First, we considered all pairs of individuals from the three geographically distant Baka groups (figure 1). Second, we considered only pairs of individuals born within the same group and discarded pairs of individuals born in different groups. To that end, we wrote a R script (R Development Core Team 2007), available upon request, which modified the Mantel test to calculate rank correlation coefficients and to permute the pairwise distances within groups only.

3. Results and discussion

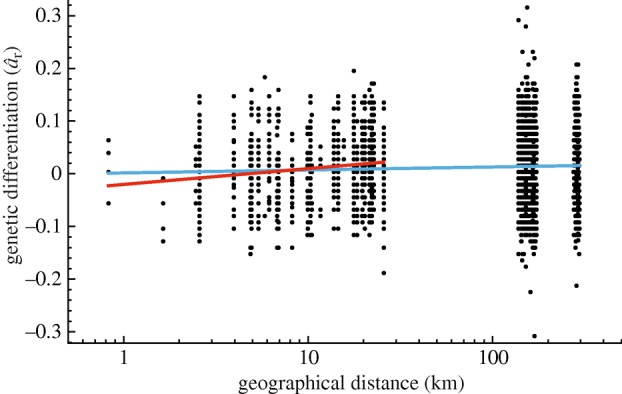

Considering all possible pairs of Baka individuals, we found a significant positive correlation between pairwise genetic distance and the logarithm of geographical distance (p = 0.010): individuals born nearby are more genetically related than individuals born further away from each other. The slope of regression between the genetic and geographical distances equalled 0.0027 (95% CI 0.0007–0.0046; see figure 2). We estimated from this slope that 4πDσ2 = 373 individuals and, using D = 0.47 individuals · km−2, we obtained σ2 = 63.2 km2. But theory shows that mutation wipes out the linear increase in genetic differentiation with geographical distance, if the distances between samples are larger than  , where μ is the mutation rate (Rousset 1997, 2004). Here, the maximum distance between any two individuals' birthplace was 296 km, a value much larger than dmax = 120 km, assuming μ = 7 × 10−4 (Zhivotovsky et al. 2003). It is therefore likely that considering the full range of geographical distances in this first analysis leads to an overestimate of σ2.

, where μ is the mutation rate (Rousset 1997, 2004). Here, the maximum distance between any two individuals' birthplace was 296 km, a value much larger than dmax = 120 km, assuming μ = 7 × 10−4 (Zhivotovsky et al. 2003). It is therefore likely that considering the full range of geographical distances in this first analysis leads to an overestimate of σ2.

Figure 2.

Correlation between genetic differentiation and the logarithm of geographical distances among Baka Pygmies. Multilocus estimates of pairwise differentiation (âr) are plotted against the logarithm of geographical distances (in kilometres). The linear regression considering all pairs of individuals is y = 0.0027x−0.0153 (in blue). The linear regression considering only pairs of individuals born within the same group is y = 0.0137x−0.1138 (in red).

Therefore, in the second analysis, we discarded all pairs of individuals born in different Baka groups and considered only pairs of individuals born nearby. We then found a stronger increase of genetic differentiation with geographical distance (slope = 0.0137; 95% CI 0.0038–0.0265; p = 0.004; figure 2) providing an estimate of 4Dπσ2 = 73 individuals, which gave σ2 = 12.4 km2. Here, the maximum distance between two sampled individuals' birthplaces (26 km) was shorter than dmax = 53 km, indicating that this estimate of σ2 should no longer be biased by mutation. But we cannot exclude that reducing the sampling scale potentially excluded some long-distance migrants, which would lead to an underestimate of σ2 (Rousset 2004).

Altogether, this suggests that the effective parent–offspring dispersal in the Baka Pygmies lies between 12.4 and 63.2 km2. These indirect estimates of effective dispersal average over male and female genetic contributions, since they are based on autosomal data. Assuming that parent–offspring dispersal distances are exponentially distributed (Cavalli-Sforza & Hewlett 1982), then half of the offspring disperse at distances shorter than  . In this case, half of the Baka offspring disperse at a maximal distance between 1.7 and 3.9 km. However, using other distributions than the exponential for the dispersal distances would provide different interpretations. Therefore, dispersal distances estimated from σ2 should be preferred here since they are independent of the (unknown) shape of the dispersal distribution.

. In this case, half of the Baka offspring disperse at a maximal distance between 1.7 and 3.9 km. However, using other distributions than the exponential for the dispersal distances would provide different interpretations. Therefore, dispersal distances estimated from σ2 should be preferred here since they are independent of the (unknown) shape of the dispersal distribution.

Without quantitative demographic data on the Baka's mobility, we used the available demographic data from the Aka Pygmies from the Central African Republic (Cavalli-Sforza & Hewlett 1982) for comparison. We calculated the second moment of the distribution of distances between birthplaces and places of residence, an estimate of σ2 from demographic data. From table 5 in Cavalli-Sforza & Hewlett (1982), we computed σ2 as  , where pi is the proportion of individuals whose birthplace and place of residence are separated by i kilometres. We found σ2 = 3599 km2 for men and 4061 km2 for women (3683 km2 on average). Hence, our estimates of the Baka's dispersal from genetic data are, respectively, 58.3 and 297 times lower than the average estimate of dispersal from demographic data in the Aka. How can this discrepancy be reconciled?

, where pi is the proportion of individuals whose birthplace and place of residence are separated by i kilometres. We found σ2 = 3599 km2 for men and 4061 km2 for women (3683 km2 on average). Hence, our estimates of the Baka's dispersal from genetic data are, respectively, 58.3 and 297 times lower than the average estimate of dispersal from demographic data in the Aka. How can this discrepancy be reconciled?

First, ethnologists show that mobility significantly differs across Pygmy populations from Central Africa (Bahuchet 1992). For instance, the mobility of the Bongo from Gabon probably decreased recently as opposed to the extended mobility of the Aka, since the Bongo nowadays live in permanent houses and widely practice agriculture (P. Verdu 2006–2007, unpublished results). In this context, the difference between our indirect estimates of dispersal in the Baka and the direct estimates in the Aka could result from differences in dispersal behaviour between these groups. Second, Cavalli-Sforza & Hewlett (1982) provide the distribution of distances between birthplaces and places of residence. This demographic data primarily reflects exploration behaviour rather than effective parent–offspring dispersal. To consistently compare demographic and genetic estimates, demographic estimates require an accurate knowledge of parents' and offspring's birthplaces, which is particularly challenging in Pygmies (Cavalli-Sforza 1986).

In conclusion, we found a strong signal of isolation by distance among the Baka Pygmies, a pattern owing to limited parent–offspring dispersal. Although our results do not challenge the view that hunter–gatherer Pygmies have frequent movements in their socioeconomic area, we demonstrate that extended individual mobility does not necessarily reflect extended dispersal across generations. Limited effective dispersal may have reinforced genetic isolation among Pygmy populations, which could be a key mechanism explaining the strong genetic differentiation found among Western Central African Pygmies, despite their recent divergence from a single ancestral population about 2800 years ago (Verdu et al. 2009).

More generally, our findings also challenge the view that mobile hunter–gatherers disperse more than sedentary farmers. Hunter–gatherers are generally described as much more mobile than agricultural populations, based on mating distances (see fig. 3 in MacDonald & Hewlett (1999)). Here, we show that Baka hunter–gatherers' dispersal is strongly localized, as is the effective dispersal previously estimated in the horticulturalist Gainj- and Kalam-speakers from New Guinea (σ2 = 1.41 km2; Rousset 1997), the only other human genetic data collected at the appropriate geographical scale for applying Rousset's (1997) regression method (Long et al. 1987). This suggests that, despite their very mobile behaviour, foragers do not necessarily disperse more than farmers.

Acknowledgements

Research and sampling authorizations were obtained from the ethical committees of both the French and the Cameroonian governments.

The authors warmly thank all donors from Cameroon. We thank Frédéric Austerlitz, Michael DeGiorgio, Ethan Jewett, Trevor Pemberton, Noah Rosenberg and two anonymous reviewers for useful suggestions. This work was funded by the CNRS, the ACI Prosodie and the ANR (grant 05-BLAN-0400-01 MPRA; programme BLANC ‘EMILE’ NT09-611697).

References

- Abéga S. C.1998Pygmées Baka: le droit à la différence. Yaoundé, Cameroon: INADES-formation Cameroun [Google Scholar]

- Bahuchet S.1992Spatial mobility and access to the resources among the African Pygmies. In Mobility and territoriality (eds Casimir M. J., Rao A.), pp. 205–257 New York, NY; Oxford, UK: Berg [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza L. L.1986African pygmies. Orlando, FL: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza L. L., Hewlett B.1982Exploration and mating range in African Pygmies. Ann. Hum. Genet. 46, 257–270 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.1982.tb00717.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGiorgio M., Jakobsson M., Rosenberg N. A.2009Explaining worldwide patterns of human genetic variation using a coalescent-based serial founder model of migration outward from Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 16 057–16 062 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0903341106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhellemmes I., Macaigne P.1985Le père des pygmées. Aventure vécue. Paris, France: Flammarion [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Prugnolle F., Manica A., Balloux F.2006A geographically explicit genetic model of worldwide human-settlement history. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79, 230–237 (doi:10.1086/505436) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J. C., Smouse P. E., Wood J. W.1987The allelic correlation structure of Gainj- and Kalam-speaking people. II. The genetic distance between population subdivisions. Genetics 117, 273–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald D. H., Hewlett B. S.1999Reproductive interests and forager mobility. Curr. Anthropol. 40, 501–523 (doi:10.1086/200047) [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N.1967The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 27, 209–220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team 2007R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S., Deshpande O., Roseman C. C., Rosenberg N. A., Feldman M. W., Cavalli-Sforza L. L.2005Support from the relationship of genetic and geographic distance in human populations for a serial founder effect originating in Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15 942–15 947 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0507611102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F.1997Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics 145, 1219–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F.2000Genetic differentiation between individuals. J. Evol. Biol. 13, 58–62 (doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00137.x) [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F.2004Genetic structure and selection in subdivided populations. Monographs in population biology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F.2008GenePop ' 007: a complete re-implementation of the GenePop software for Windows and Linux. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 8, 103–106 (doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H.1992Notes on the distribution and settlement pattern of hunter–gatherers in Northwestern Congo. African Study Monographs 13, 203–216 [Google Scholar]

- Tsuru D.2001Generation and transaction processes in the spirit ritual of the Baka Pygmies in Southeast Cameroon. Afric. Stud. Monographs, Suppl. 27, 103–123 [Google Scholar]

- Vallois H. V., Marquer P.1976Les Pygmées Baka du Cameroun: anthropologie et ethnographie. Mémoires du Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Série A, Tome C. Paris, France: Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle [Google Scholar]

- Verdu P., et al. 2009Origins and genetic diversity of pygmy hunter-gatherers from Western Central Africa. Curr. Biol. 19, 312–318 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhivotovsky L. A., Rosenberg N. A., Feldman M. W.2003Features of evolution and expansion of modern humans, inferred from genomewide microsatellite markers. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1171–1186 (doi:10.1086/375120) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]