Abstract

Long-term studies have revealed population declines in fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. In birds, and particularly amphibians, these declines are a global phenomenon whose causes are often unclear. Among reptiles, snakes are top predators and therefore a decline in their numbers may have serious consequences for the functioning of many ecosystems. Our results show that, of 17 snake populations (eight species) from the UK, France, Italy, Nigeria and Australia, 11 have declined sharply over the same relatively short period of time with five remaining stable and one showing signs of a marginal increase. Although the causes of these declines are currently unknown, we suspect that they are multi-faceted (such as habitat quality deterioration, prey availability), and with a common cause, e.g. global climate change, at their root.

Keywords: snakes, sharp population declines, carrying capacity, global climate change

1. Introduction

There is growing evidence from long-term studies of worldwide declines in vertebrate populations: fishes (Harshbarger et al. 2000; Light & Marchetti 2007), amphibians (Wake 1991; Alford et al. 2001), reptiles (Gibbons et al. 2000; Winne et al. 2007), birds (King et al. 2008) and mammals (Mcloughlin et al. 2003). Some of these declines can be directly attributable to known causes, e.g. pollution (Harshbarger et al. 2000), habitat loss/change (Gibbons et al. 2000; Feyrer et al. 2007), disease (Pounds et al. 2006; LaDeau et al. 2007), over-exploitation (Whitehead et al. 1997) or climate change (Collins & Storfer 2003; Reading 2007), while for others, the causes remain either unclear (Kiesecker et al. 2001; Collins & Storfer 2003) or unknown (Gibbons et al. 2000; Winne et al. 2007). Although there is little evidence that snake populations are in decline, there are reports for other reptiles (Gibbons et al. 2000) and there is consensus, among herpetologists, that snakes may, indeed, be disappearing worldwide (Mullin & Seigel 2009). One possible reason for this view is the relative lack of long-term individual-based studies of snake populations. Our data represent the first evidence that some species occurring in the tropics (Nigeria) have shown similar patterns of decline to others found in southern (Italy), central (France) and northern Europe (UK).

2. Material and methods

We used data from studies of geographically widespread snake populations covering a broad diversity of snake lineages and environmental situations to determine changes in status over time (table 1). Survey methodologies were identical between years at each study site but not between sites. Coronella austriaca (Ca) and Natrix natrix (Nn1) were surveyed one day per week for 21 weeks annually (April–October). Vipera aspis (Va1) was surveyed five days per week for five months annually. Hierophis viridiflavus (Hv1) and Zamenis longissimus (Zl1) were sampled using daily collections of road-kills for five months annually. Hierophis viridiflavus (Hv2), Z. longissimus (Zl2) and N. natrix (Nn2) were surveyed three days per week for five months annually. Notechis scutatus (Ns) was surveyed for two weeks each spring. Vipera aspis (Va2,3) was surveyed one day per week annually (March–November). Vipera ursinii (Vu1,2) was surveyed one day per week annually (April–October). Bitis gabonica (Bg), B. nasicornis (Bn), Python regius (Pr) and Dendroaspis jamesoni (Dj) were all studied in sympatry for two days per week annually (May–October). Importantly, the methods used to monitor population trends were consistent through time at each site. Although we used simple techniques to count snake numbers, we nevertheless obtained only two distinct clear patterns (see §3), showing that uncontrolled factors (e.g. catchability, annual climatic fluctuations) did not obscure the detection of major trends. For all populations (excluding road-kills), we collected capture–mark–recapture data, as we intended to produce demographic parameters. However, since the resulting population estimates correlated with count data, we opted to use the latter because they were similar to road-kill counts. Although simple counting underestimates true population size (X. Bonnet, J. M. Ballouard & G. Naulleau 1993–2009, unpublished data), it does provide an index of abundance. We used the simplest methods for consistency among study cases and sites, and also for conciseness. Each captured individual in each independent study was given a permanent individual mark, using either ventral scale clipping or pit-tagging (passive integrated transponder), and thus the current study did not include pseudo-replicates (re-sampling the same individuals within a year was thus avoided). Importantly, several snake populations were monitored in well-protected areas (e.g. Chizé Natural Reserve, Gran Sasso National Park), where habitats were not directly perturbed by human intervention.

Table 1.

Site locations, study duration and responsible authors for each species. Ca, Coronella austriaca; Nn, Natrix natrix; Va, Vipera aspis; Hv, Hierophis viridiflavus; Zl, Zamenis longissimus; Vu, Vipera ursinii; Bg, Bitis gabonica; Bn, Bitis nasicornis; Pr, Python regius; Dj, Dendroaspis jamesoni; Ns, Notechis scutatus.

| species | country | site status | latitude | longitude | duration | researcher |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | UK | protected | 50°44′ N | 2°08′ W | 1997–2009 | CJR |

| Nn1 | UK | protected | 50°44′ N | 2°08′ W | 1997–2009 | CJR |

| Va1 | France | unprotected | 47°04′ N | 2°00′ W | 1993–2008 | GN/XB |

| Hv1 | France | unprotected | 46°07′ N | 0°25′ W | 1995–2009 | XB/JMB |

| Zl1 | France | unprotected | 46°07′ N | 0°25′ W | 1994–2009 | XB/JMB |

| Hv2 | France | protected | 46°07′ N | 0°25′ W | 1997–2009 | XB/JMB |

| Zl2 | France | protected | 46°07′ N | 0°25′ W | 1997–2009 | XB/JMB |

| Nn2 | France | protected | 46°07′ N | 0°25′ W | 1995–2009 | XB/JMB |

| Va2 | Italy | protected | 43°16′ N | 11°09′ E | 1989–2008 | LML/LR/GA |

| Va3 | Italy | protected | 43°42′ N | 10°30′ E | 1989–2009 | LML/LR/GA |

| Vu1 | Italy | protected | 42°27′ N | 13°42′ E | 1987–2008 | EF/LML/GA |

| Vu2 | Italy | protected | 42°22′ N | 13°43′ E | 1987–2008 | EF/LML/GA |

| Bg | Nigeria | protected | 4°38′ N | 7°55′ E | 1995–2008 | GCA/LML |

| Bn | Nigeria | protected | 4°38′ N | 7°55′ E | 1995–2008 | GCA/LML |

| Pr | Nigeria | protected | 4°38′ N | 7°55′ E | 1995–2008 | GCA/LML |

| Dj | Nigeria | protected | 4°38′ N | 7°55′ E | 1995–2008 | GCA/LML |

| Ns | Australia | protected | 32°07′ S | 115°39′ E | 1997–2009 | XB/DP |

All statistical tests were two-tailed, with alpha set at 5 per cent. Data normality were tested prior to using parametric tests.

3. Results

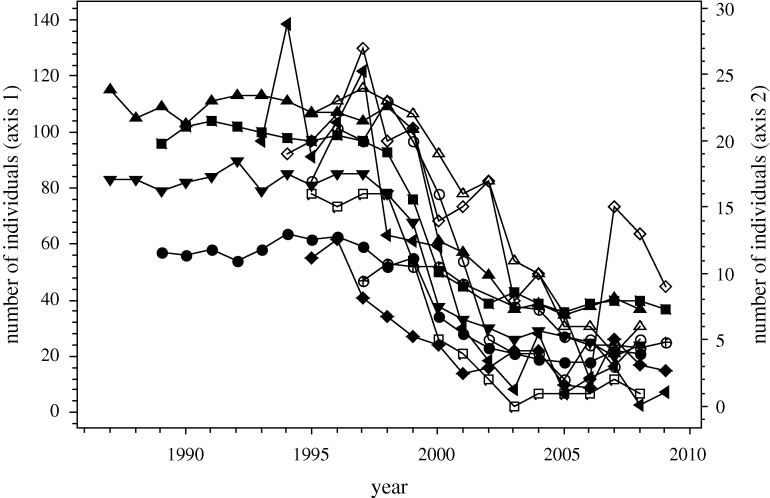

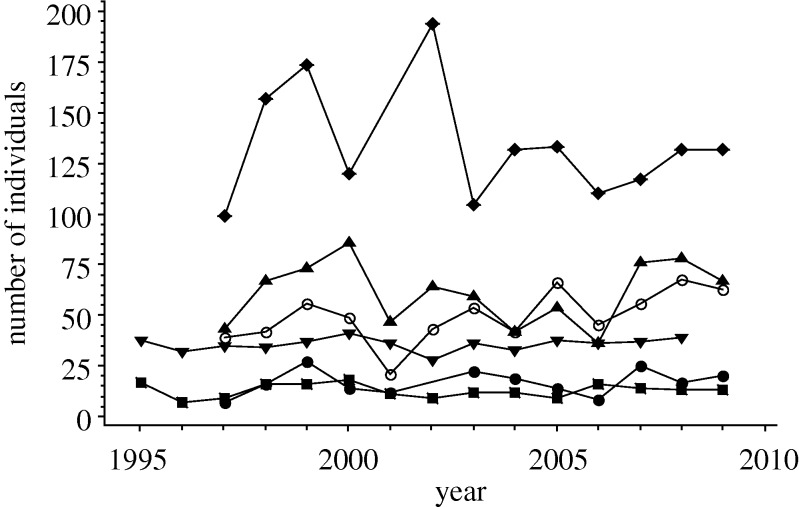

Our data revealed an alarming trend. The majority of snake populations had declined sharply, and synchronously (figure 1), while a few had remained stable (one species from the UK (Nn1), two from mainland Europe (Nn2, Zl2), one from Nigeria (Dj) and one from Australia (Ns)) and one showed evidence of a very weak increase (Hv2) (figure 2). All the stable populations were situated in protected areas while all the populations occurring in areas subject to increasing anthropogenic pressures declined (table 1). However, eight snake populations from protected areas (Ca, Va2,3, Vu1,2, Bg, Bn, Pr) also exhibited large and surprisingly similar patterns of decline. Most of the declining populations exhibited a ‘tipping point’ effect (Andersen et al. 2008), with a period of relative stability, up until about 1998, followed by a steep decline, over a period of approximately 4 years, and then a second period of relative stability, but at reduced population densities and with no subsequent sign of recovery to pre-crash levels.

Figure 1.

Annual total number of individuals found for each declining snake species population. Axis 1: filled left-pointed triangles, Va1; filled circles, Va2; filled squares, Va3; filled triangles, Vu1; filled inverted triangles, Vu2; cirlces with crosses, Ca; filled diamonds, Hv1. Axis 2: open circles, Bg; open squares, Bn; open triangles, Pr; open diamonds, Zl1. Values shown for Va1 are one-third of true values. See table 1 for key to snake species abbreviations and country of origin.

Figure 2.

Annual total number of individuals found for five stable and one increasing snake species population. Filled circles, Nn1; filled squares, Nn2; filled triangles, Zl2; filled inverted triangles, Dj; open circles, Hv2; filled diamonds, Ns. Linear regression analyses of the change in the number of individuals of each species present over time. Stable populations: Nn1-nos = −684 + 0.350 year, p = 0.476, r2 = 0.052, n = 12; Nn2-nos = 6 + 0.04 year, p = 0.987, r2 = 0.0, n = 15; Zl2-nos = −522 + 0.290 year, p = 0.814, r2 = 0.005, n = 13; Dj-nos = −237 + 0.136 year, p = 0.548, r2 = 0.031, n = 14; Ns-nos = 2936–1.40 year, p = 0.537, r2 = 0.039, n = 12. Increasing population: Hv2-nos = −3813 + 1.93 year, p = 0.037, r2 = 0.339, n = 13. See table 1 for a key to species abbreviations.

The observed population declines were not uniform across the sexes (table 2) such that, with the exception of Z. longissimus (Zl1), there was a significant difference (Student's t = 2.64, d.f. = 12, p = 0.022) between the mean decline of females (mean = 81.2%, s.d. = 8.071, n = 10, range: 69.5–96.0%) and males (mean = 63.8%, s.d. = 19.22, n = 10, range: 25.2–89.2%). However, although there was no significant difference (t = −1.45, d.f. = 3, p = 0.243) between the magnitude of the decline of females from Europe (mean = 78.9%, s.d. = 7.39, n = 7) and Nigeria (mean = 86.7%, s.d. = 8.03, n = 3) there was one (t = −2.43, d.f. = 7, p = 0.045) between that of males from Europe (mean = 57.2%, s.d. = 18.80, n = 7) and Nigeria (mean = 79.2%, s.d. = 9.71, n = 3). The sex ratio within the stable populations did not change over time.

Table 2.

Comparing the mean numbers of individuals (male and female) found each year before and after the observed decline of each species shown in figure 1. See table 1 for a key to species abbreviations. Comparisons between means were made using Student's t-test.

| species | sex | period (before) | mean (n) | period (after) | mean (n) | comparing means |

decline (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | p | d.f. | |||||||

| Ca | ♂ | 1997–2001 | 27.8 (5) | 2004–2009 | 20.8 (6) | 3.07 | 0.015 | 8 | 25.2 |

| ♀ | 1997–2001 | 22.2 (5) | 2004–2009 | 5.8 (6) | 11.29 | <0.0001 | 5 | 73.9 | |

| Va1 | ♂ | 1993–1997 | 163.2 (5) | 2002–2009 | 26.6 (8) | 9.11 | <0.0001 | 5 | 83.7 |

| ♀ | 1993–1997 | 168.0 (5) | 2002–2009 | 10.9 (8) | 9.46 | 0.001 | 4 | 93.5 | |

| Hv1 | ♂ | 1995–1996 | 40.0 (2) | 2001–2009 | 12.8 (9) | 8.04 | 0.079 | 1 | 68.0 |

| ♀ | 1995–1996 | 18.5 (2) | 2001–2009 | 4.0 (9) | 15.14 | <0.0001 | 7 | 78.4 | |

| Zl1 | ♂ | 1994–1999 | 16.0 (6) | 2003–2009 | 5.4 (7) | 6.27 | <0.0001 | 9 | 66.2 |

| ♀ | 1994–1999 | 5.5 (6) | 2003–2009 | 3.7 (7) | 1.63 | 0.134 | 10 | 32.7 | |

| Va2 | ♂ | 1989–1999 | 32.4 (11) | 2002–2008 | 14.9 (7) | 16.61 | <0.0001 | 15 | 54.0 |

| ♀ | 1989–1999 | 25.6 (11) | 2002–2008 | 5.5 (7) | 35.57 | <0.0001 | 15 | 78.5 | |

| Va3 | ♂ | 1989–1998 | 57.5 (10) | 2002–2009 | 30.9 (8) | 26.05 | <0.0001 | 15 | 46.3 |

| ♀ | 1989–1998 | 41.3 (10) | 2002–2009 | 8.3 (8) | 39.37 | <0.0001 | 15 | 79.9 | |

| Vu1 | ♂ | 1987–1999 | 60.3 (13) | 2003–2008 | 27.5 (6) | 24.64 | <0.0001 | 16 | 54.4 |

| ♀ | 1987–1999 | 48.0 (13) | 2003–2008 | 10.3 (6) | 41.96 | <0.0001 | 16 | 78.5 | |

| Vu2 | ♂ | 1987–1999 | 46.3 (13) | 2003–2008 | 14.3 (6) | 24.34 | <0.0001 | 16 | 69.1 |

| ♀ | 1987–1999 | 35.4 (13) | 2003–2008 | 10.8 (6) | 25.05 | <0.0001 | 15 | 69.5 | |

| Bg | ♂ | 1995–1999 | 10.8 (5) | 2002–2008 | 2.3 (7) | 18.09 | <0.0001 | 8 | 78.7 |

| ♀ | 1995–1999 | 9.4 (5) | 2002–2008 | 1.7 (7) | 10.93 | <0.0001 | 4 | 81.9 | |

| Bn | ♂ | 1995–1998 | 8.3 (4) | 2002–2008 | 0.9 (7) | 20.46 | <0.0001 | 8 | 89.2 |

| ♀ | 1995–1998 | 7.5 (4) | 2002–2008 | 0.3 (7) | 21.06 | <0.0001 | 5 | 96.0 | |

| Pr | ♂ | 1995–1999 | 12.6 (5) | 2005–2008 | 3.8 (4) | 15.58 | <0.0001 | 5 | 69.8 |

| ♀ | 1995–1999 | 10.2 (5) | 2005–2008 | 1.8 (4) | 11.92 | <0.0001 | 5 | 82.3 | |

4. Discussion

The snake population declines shown by these data, though alarming, remain observational as we have no firm evidence to suggest possible causes. Two-thirds of the monitored populations collapsed, and none have shown any sign of recovery over nearly a decade since the crash. Unfortunately, there is no reason to expect a reversal of this trend in the future. Interestingly, six of the eight declining species are characterized by having small home ranges, sedentary habits and ambush foraging strategies while, with the exception of N. scutatus (Ns), whose movements are restricted by the small size of the island on which it occurs, all of the stable/increasing species are wide ranging, active foragers (Luiselli et al. 2000). These patterns fit the prediction that ‘sit-and-wait foragers may be vulnerable because (i) they rely on sites with specific types of ground cover, and anthropogenic activities disrupt these habitat features, and (ii) ambush foraging is associated with a suite of life-history traits that involve low rates of feeding, growth and reproduction’ (Reed & Shine 2002).

In Europe, although habitat loss/change may be the main cause of these declines, other factors, such as prey availability, habitat edge destruction and pollution, may also be involved because several declines occurred in well-protected areas. A similar scenario may have also occurred in Nigeria, where the study sites that included both declining and stable populations were adjacent to the Stubbs Creek Forest Reserve, which is a well-protected area. Nevertheless, the shape of the observed population declines, leading to significantly reduced snake densities after the ‘crash' is indicative of a change in habitat quality, rather than habitat loss, with a subsequent reduction in its carrying capacity, e.g. reduced prey availability (Mcloughlin et al. 2003). It is possible that the declines are co-incidental and that the causes vary between sites. However, this seems unlikely as all the declines occurred during the same relatively short period of time and over a wide geographical area that included temperate, Mediterranean and tropical climates. We suggest that, for these reasons alone, there is likely to be a common cause at the root of the declines and that this indicates a more widespread phenomenon (Pounds et al. 2006; Feyrer et al. 2007; LaDeau et al. 2007). For instance, synchrony could be attributable to common stochastic environmental factors (Weatherhead et al. 2002); worldwide and synchronized declines have been already observed in amphibians (Pounds et al. 2006). Although, in this study, the small sample size (17 populations of eight species) with taxonomic, geographical and ecological biases makes extrapolation difficult, the declines are sufficiently striking to warrant attention.

Overall, the worrying trends we report suggests that snake researchers should work more closely with one another to better identify the factors responsible for the widespread population declines of snakes in order to understand, stop and ultimately reverse them.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by NAOC, Aquater Snamprogetti, T.S.K.J., ENI, Chelonian Research Foundation, Turtle Conservation Fund and Conservation International (Nigeria), Gran Sasso-Monti della Laga National Park, RomaNatura (Italy, CG79, CNRS (France), ARC and DEP (Australia). Permits were issued by Natural England (UK), Gran Sasso-Monti della Laga National Park (Italy) and the Federal Department of Forestry (Nigeria). Field co-workers included F.M. Angelici, C. Anibaldi, D. Capizzi, M. Capula, E.A. Eniang and O. Lourdais, as well as many students and volunteers who cannot be cited.

References

- Alford R. A., Dixon P. M., Pechmann J. H. K.2001Global amphibian population declines. Nature 412, 499–500 (doi:10.1038/35087658) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen T., Carstensen J., Hernández-García E., Duarte C. M.2008Ecological thresholds and regime shifts: approaches to identification. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. P., Storfer A.2003Global amphibian declines: sorting the hypotheses. Divers. Distrib. 9, 89–98 [Google Scholar]

- Feyrer F., Nobriga M. L., Sommer T. R.2007Multidecadal trends for three declining fish species: habitat patterns and mechanisms in the San Fransisco estuary, California, USA. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 64, 723–734 (doi:10.1139/F07-048) [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons J. W., et al. 2000The global decline of reptiles, déjà vu amphibians. Bioscience 50, 653–666 [Google Scholar]

- Harshbarger J. C., Coffey M. J., Young M. Y.2000Intersexes in Mississippi River shovelnose sturgeon sampled below Saint Louis, Missouri, USA. Mar. Environ. Res. 50, 247–250 (doi:10.1016/S0141-1136(00)00055-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesecker J. M., Blaustein A. R., Belden L. K.2001Complex causes of amphibian declines. Nature 410, 681–684 (doi:10.1038/35070552) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D. I., Lambert J. D., Buonaccorsi J. P., Prout L. S.2008Avian population trends in the vulnerable montane forests of the northern Appalachians, USA. Biodivers. Conserv. 17, 2691–2700 (doi:10.1007/s10531-007-9244-9) [Google Scholar]

- LaDeau S. L., Kilpatrick A. M., Marra P. P.2007West Nile virus emergence and large-scale declines of North American bird populations. Nature 447, 710–714 (doi:10.1038/nature05829) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light T., Marchetti M. P.2007Distinguishing between invasions and habitat changes as drivers of diversity loss among California's freshwater fishes. Conserv. Biol. 21, 434–446 (doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00643.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiselli L., Angelici F. M., Akani G. C.2000Large elapids and arboreality: the ecology of Jameson's green mamba (Dendroaspis jamesoni) in an Afrotropical forested region. Contrib. Zool. 69, http://dpc.uba.uva.nl/ctz/vol69/nr03/art01 [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin P. D., Dzus E., Wynes B., Boutin S.2003Declines in populations of woodland caribou. J. Wildl. Manage. 67, 755–761 [Google Scholar]

- Mullin S. J., Seigel R. A.2009Snakes: ecology and conservation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press [Google Scholar]

- Pounds J. A., et al. 2006Widespread amphibian extinctions from epidemic disease driven by global warming. Nature 439, 161–167 (doi:10.1038/nature04246) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading C. J.2007Linking global warming to amphibian declines through its effects on female body condition and survivorship. Oecologia 151, 125–131 (doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0558-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R. N., Shine R.2002Lying in wait for extinction? Ecological correlates of conservation status among Australian elapid snakes. Conserv. Biol. 16, 451–461 [Google Scholar]

- Wake D. B.1991Declining amphibian populations. Science 253, 860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherhead P. J., Blouin-Demers G., Prior K. A.2002Synchronous variation and long-term trends in two populations of black rat snakes. Conserv. Biol. 16, 1602–1608 [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead H., Christal J., Dufault S.1997Past and distant whaling and the rapid decline of sperm whales off the Galapagos Islands. Conserv. Biol. 11, 1387–1396 [Google Scholar]

- Winne C. T., Willson J. D., Todd B. D., Andrews K. M., Gibbons J. W.2007Enigmatic decline of a protected population of eastern kingsnakes, Lampropeltis getula, in South Carolina. Copeia 2007, 507–519 (doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2007)2007[507:EDOAPP]2.0.CO;2) [Google Scholar]