Abstract

Background and objectives: The United States Renal Data System (USRDS) is a commonly utilized database for epidemiologic research of ESRD patients. USRDS uses Medical Evidence Form 2728 to collect medical information about ESRD patients. The validity of the Form 2728 “primary cause of renal failure” field for glomerular diseases has not been evaluated, although inconsistencies between Form 2728 information and medical records have been documented previously with respect to comorbidities.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Form 2728 information was linked with renal biopsy results from the Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network (GDCN) for 217 patients with biopsy-confirmed glomerular diseases who had reached ESRD. Biopsy results were compared with the Form 2728 “primary cause of renal failure” field. Diseases were considered individually, and also categorized into commonly used disease groups. Percentage of agreement and disease-specific measures of validity were calculated.

Results: Overall agreement between renal biopsy and Form 2728 was low (14.8% overall, 23.0% when categorized). Agreement was better after Form 2728 was revised in 1995 (10.0% before versus 23.2% after overall). The cause of ESRD field was left blank in 57% of the forms submitted for glomerular disease patients. Individual glomerular diseases had very low specificities, but tended to have high positive predictive values.

Conclusions: Form 2728 does not accurately reflect the renal pathology diagnosis as captured by biopsy. The large degree of missing data and misclassification should be of concern to those performing epidemiologic research using Form 2728 information on glomerular diseases.

Individual glomerular diseases are rare, yet combined they account for approximately 10% of ESRD in the United States (1), creating a large burden of morbidity, mortality, cost, and loss of quality of life (1). Epidemiologic research of glomerular diseases is limited due to the rarity of individual disease types, the difficulty in correctly diagnosing them, and the lack of accurate disease data. Most epidemiologic studies rely upon biopsy results for accurate disease information (2–4).

Approximately 95% of patients with incident ESRD in the United States are eligible for Medicare coverage. To document ESRD and justify payment from Medicare, the primary cause of renal failure and other medical information is collected at the time of ESRD onset on Medical Evidence Form 2728. The form is completed by a physician and reported to a regional ESRD Network, which collaborates and shares data with the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). These data are incorporated into the USRDS data analysis files and used in research of ESRD patients, including those with glomerular disease (5–11). Previous research has analyzed the validity of the comorbidities section of Form 2728, revealing under-reporting of almost all conditions compared with medical records, with sensitivities 50% or less for 11 of the 17 comorbid conditions considered (12). These results suggest that Form 2728 may be inaccurate in the reporting of medical information.

Form 2728 currently lists 70 International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes in 8 disease categories representing “the only acceptable causes of end stage renal disease,” from which the physician must select the most appropriate cause of ESRD for the patient. If there is more than one condition present, the instructions indicate the physician is to select the primary cause of ESRD. The validity of USRDS “primary cause of renal failure” codes relative to renal biopsy has not been evaluated. If the USRDS database is to be used as a proxy for the gold standard of renal biopsy in the research of ESRD in glomerular disease patients, it is necessary that the agreement between them be measured and understood.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

The Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network (GDCN) was established in 1984 as an organization of nephrologists throughout the southeastern United States. In 1985 it established registries of patients with glomerular diseases (vasculitis, lupus nephritis, and membranous glomerulopathy, with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, IgA nephropathy, and others added later) whose renal biopsies were evaluated and confirmed at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Nephropathology Laboratory. Private practices, hospitals, and academic centers throughout the southeastern United States send renal biopsies to the UNC Nephropathology Laboratory for evaluation. Patients whose renal biopsies result in a diagnosis in one of the GDCN′s disease registries are contacted through their referring physicians, and long-term consent is obtained from them for inclusion in the registry and related research studies (13–19).

The GDCN contained 1286 biopsies representing 1157 individuals between March 1979 and May 2000. Of these patients, 337 were known to have reached ESRD, as defined by initiating dialysis or receiving a pre-emptive renal transplant, and were included in our sample. Biopsies of transplanted kidneys were excluded. Identifying information, including name, birth date, and social security number (where available, as it was not collected originally by the GDCN) were transmitted to ESRD Network 6 (including North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia) and matched with their corresponding Form 2728 by Network 6 staff. The “primary cause of renal failure” code was extracted and linked with the GDCN biopsy results.

Date of ESRD was determined from the Form 2728 date listed with ESRD Network 6. Where this date was missing, date of first dialysis or transplant on record with the GDCN was used as ESRD onset.

This analysis was approved by the UNC Biomedical Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analyses

The gold standard classification was created by three clinicians (two nephrologists and one pathologist) assigning an ICD-9-CM code from the Form 2728 list of conditions corresponding most closely to potential renal biopsy results.

Gold standard, individual disease diagnosis codes, and also diagnosis categories, from the renal biopsy primary diagnosis, were compared with the reported Form 2728 codes and categories on file with Network 6. Values missing on Form 2728 were retained as incorrect matches, but additional analyses were restricted to individuals with “nonmissing” Form 2728 values. Percentage of agreement, both for individual diseases and within disease categories, was calculated as an overall measure of accuracy of the database. Percentage of agreement was stratified by several variables—sex, race (white versus black), ESRD onset resulting in dialysis versus transplant, biopsy performed before or after ESRD onset, primary nephrologist at UNC versus other, and Form 2728 filed before 1995 or during or after 1995—and compared using χ2 tests.

Because of controversy and disagreement regarding classification of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody–associated (ANCA-associated) vasculitis (20), Wegener granulomatosis (WG) (which is a Form 2728 option) was considered separately from other forms of vasculitis and collapsed into the “vasculitis and its derivatives” category.

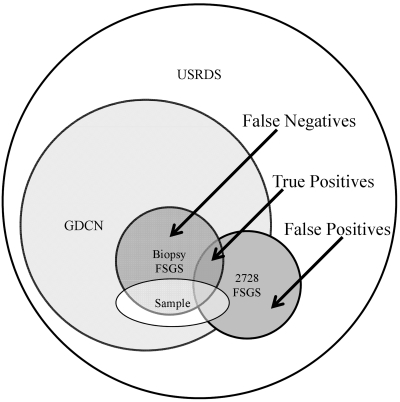

To test the accuracy of individual diagnosis codes, patients were categorized as having or not having the disease according to renal biopsy as the gold standard, and Form 2728 (individuals with missing values retained). For those diseases with more than ten affected individuals by biopsy report, sensitivities, positive predictive values (PPV), and false positive (FP) rates (1 − specificity) were calculated. Because of the sampling frame (see Figure 1), true negatives were under-represented, as those who reached ESRD without the need for a biopsy (e.g., primary hypertension and diabetes) would not be eligible for inclusion in the sample. Thus, specificity could not be accurately calculated. False positives are also under-represented by our sampling structure, as nonglomerular disease patients labeled as having the particular glomerular disease under investigation would not be included in the sample. We therefore assume that those with nonglomerular diseases would very rarely be labeled as having a glomerular disease requiring a biopsy for diagnosis. The FP rate and PPV is thus conditional on the fact that a patient has a biopsy-confirmed glomerular disease (21).

Figure 1.

Sampling frame for an individual glomerular disease, using FSGS as an example.

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Matching resulted in 227 successful matches of GDCN ESRD patients' renal biopsies to Form 2728. A failure to match may have resulted from name changes where social security number was not available or the patient's Form 2728 may have been filed in a different ESRD Network, as the GDCN has a broader geographic reach than Network 6. Ten patients were excluded because of their biopsies being performed on a renal allograft, resulting in 217 patients for analysis. Patients were predominantly white and were evenly split between men and women (see Table 1). Biopsies were performed an average of 1.8 years before onset of ESRD (SD 3.1 years). Thirteen percent (n = 30) had a secondary diagnosis listed on the biopsy report, with two patients having two secondary diagnoses.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| men | 103 (47) |

| women | 114 (53) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| white | 128 (59) |

| black | 79 (36) |

| other | 3 (1) |

| unknown | 7 (3) |

| Age at biopsy, mean (SD) | 50.5 (20.2) |

| Age at ESRD, mean (SD) | 51.7 (19.5) |

| Years between biopsy and ESRD, mean (SD) | 1.8 (3.1) |

Overall percentage of agreement between biopsy report and Form 2728 was 14.8% for individual diseases and 23.0% for disease categories. Percentage of agreement for individual diseases and categories did not differ by sex, race (white versus black), whether the patient's primary nephrologist was a UNC physician, or whether the biopsy was performed before or after the initiation of dialysis (see Table 2). There were only five patients whose initial ESRD treatment was transplant, making comparison of transplant and dialysis patients impractical. Agreement was better after 1995, when administrative changes to the form updated the list of potential diagnoses (5) (see Table 3). This improvement is due to both a reduction in missing Form 2728 diagnoses (63.1% missing before 1995; 45.1%, missing during or after 1995) and more agreement in stated codes among the nonmissing (27.1% correctly matched before 1995, 42.2% correctly matched during and after 1995).

Table 2.

Percentage of agreement between renal biopsy and Form 2728 by several characteristics

| n | % Agreement | χ2 | df | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-specific | |||||

| overall | 217 | 14.8 | |||

| Form 2728 classification “nonmissing” | 93 | 34.4 | |||

| biopsy relation to ESRD | 0.36 | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| biopsy before ESRD | 178 | 14.6 | |||

| biopsy after ESRD | 32 | 18.8 | |||

| race | 2.79 | 1 | 0.09 | ||

| white | 128 | 11.7 | |||

| black | 79 | 20.3 | |||

| sex | 0.10 | 1 | 0.8 | ||

| men | 103 | 15.5 | |||

| women | 114 | 14.0 | |||

| primary nephrologist | 0.44 | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| UNC-based | 69 | 17.4 | |||

| other | 144 | 13.9 | |||

| Disease categories | |||||

| overall | 217 | 23.0 | |||

| Form 2728 classification “nonmissing” | 93 | 53.8 | |||

| biopsy relation to ESRD | 0.03 | 1 | 0.9 | ||

| biopsy before ESRD | 178 | 23.6 | |||

| biopsy after ESRD | 32 | 25.0 | |||

| race | 0.32 | 1 | 0.6 | ||

| white | 128 | 21.9 | |||

| black | 79 | 25.3 | |||

| sex | 0.31 | 1 | 0.6 | ||

| men | 103 | 21.4 | |||

| women | 114 | 24.6 | |||

| primary nephrologist | 0.17 | 1 | 0.7 | ||

| UNC-based | 69 | 21.7 | |||

| other | 144 | 24.3 |

Table 3.

Percentage of agreement between renal biopsy and Form 2728, before and after 1995

| Overall (n = 217) | <1995 (n = 130) | ≥1995 (n = 82) | χ2 | df | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual diseases | 14.8 | 10.0 | 23.2 | 6.81 | 1 | 0.009 |

| Disease categories | 23.0 | 17.7 | 32.9 | 6.48 | 1 | 0.01 |

When all ANCA vasculitis was grouped into one category, agreement improved to 16.6% overall, 38.7% among the nonmissing. Of those labeled “vasculitis and its derivatives” on Form 2728 (n = 68), 6% had WG on biopsy. Of those labeled WG on Form 2728 (n = 10), none had a biopsy finding consistent with non-WG ANCA vasculitis.

The validity of five individual glomerular diseases was estimated (see Table 4): WG, systemic lupus erythematosus, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, membranous nephropathy, and amyloidosis. Sensitivity tended to be very low for all diseases (≤0.30), whereas PPV were high (>0.90), except for WG (PPV = 0.38), indicating that for any one of these diseases, a stated diagnosis on Form 2728 was generally accurate (except for WG), but the vast majority of patients with the disease in question were not labeled as such on the form (either because the wrong diagnosis was labeled or the field was left blank). False positive rates were very low (≤0.02) for the sample (see Table 2), indicating that a low proportion of other glomerular disease patients were incorrectly labeled as having ESRD caused by one of these diseases.

Table 4.

Disease-specific measures of validity

| Cases (Biopsy) | Cases (Form 2728) | Sensitivity | 95% CI | PPV | 95% CI | FP Rate | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual disease | ||||||||

| Wegener granulomatosis | 10 | 8 | 0.30 | 0.07, 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.09, 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.06 |

| lupus erythematosus | 30 | 8 | 0.27 | 0.12, 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.63, 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.02 |

| FSGS | 38 | 11 | 0.26 | 0.13, 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.59, 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.00, 0.03 |

| membranous nephropathy | 27 | 5 | 0.19 | 0.06, 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.48, 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.02 |

| amyloidosis | 16 | 2 | 0.13 | 0.02, 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.16, 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.02 |

| Disease categories | ||||||||

| GN | 76 | 50 | 0.37 | 0.26, 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.41, 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.10, 0.23 |

| neoplasms/tumors | 23 | 4 | 0.17 | 0.05, 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.40, 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.02 |

| secondary GN/vasculitis | 108 | 19 | 0.17 | 0.10, 0.24 | 0.95 | 0.74, 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.00, 0.05 |

The validity of three disease categories was analyzed: glomerulonephritis (GN), neoplasms/tumors, and secondary GN/vasculitis. For GN, sensitivity was low (0.37), as was the PPV (0.56), indicating that many true GN patients were not labeled as such on Form 2728, whereas many of those labeled as having GN, in fact, did not have biopsy results consistent with GN. The false positive rate was high (0.16), indicating that many patients in our sample from other disease categories were incorrectly labeled as having GN-caused ESRD on Form 2728. Secondary GN/vasculitis and neoplasms/tumors categories had similar results: very low sensitivity (0.17 for both), high PPV (≥0.95), and low false positive rates (≤0.01).

Discussion

Accurate disease information is crucial for valid research, and the process by which disease information is stored in data sources must be understood and considered carefully. In 1995, the list of conditions attached to Form 2728 was updated, dropping and combining some diagnoses. These adjustments impacted the reporting of glomerular diseases, evidenced by sharp increases in the number of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and other glomerular diseases reported in 1995 and thereafter (5), demonstrating that changes in Form 2728 reporting can alter disease classification in the USRDS database. This may have a substantial effect on research using USRDS data on glomerular diseases.

Our results suggest that the “primary cause of renal failure” field on Medical Evidence Form 2728 is not a reliable proxy for renal biopsy results for glomerular diseases. It does not appear that biopsy results are generally considered while completing Form 2728, as agreement does not change whether or not there was a biopsy performed previous to ESRD onset. There are several potential explanations for these discrepancies, including physician error, lack of available biopsy data, and causes more proximal to ESRD than renal histopathology.

Form 2728 must be submitted to the local ESRD network within 60 days of ESRD onset. The form may be completed by a physician without direct knowledge of the patient or access to the patient's medical records. Of those labeled “glomerulonephritis (histologically not examined)” (n = 19), 95% had a renal biopsy performed before filing of Form 2728, indicating biopsy results may not be considered or accessed while filling out Form 2728. In cases of sudden kidney failure, a biopsy may not have been performed at the initiation of dialysis. A very large proportion (57.1%) of the sample was missing a cause of ESRD code on Form 2728. In many cases, this may be because the physician had no access to biopsy information or patients' medical histories.

There may also be factors contributing to ESRD etiology other than glomerular pathology. Causality of a complex condition like ESRD can be difficult to define, having numerous components particular to an individual (22). The potential causes of ESRD listed on Form 2728 contain a mixture of renal pathologies, systemic disorders, and other risk factors for ESRD. It is possible for a patient to have multiple conditions which contributed to his/her ESRD. Etiologically, the underlying pathology may not always be the most direct cause of ESRD, and biopsies in this sample were performed up to 13.6 years before ESRD, allowing time for the development of additional conditions. Form 2728 is then not designed to specifically capture histopathology, but rather, the physician's best interpretation of the “primary” cause.

This current study has limitations in its generalizability. Our sample was taken from a limited geographic region. Also, as our sample is not representative of the entire spectrum of ESRD causes, the sensitivity and negative predictive value for diseases and categories could not be calculated. Also, the PPV depends on the assumption that those with nonglomerular diseases in USRDS would not be labeled as having a glomerular disease. If this assumption is not met, the calculated PPV would overestimate the true PPV.

This analysis only considers 2728 Forms completed before 2001. Electronic medical records have become more widespread in the past decade, allowing easier access to prior health information in many cases. This may have had an effect on the accuracy of Form 2728 reporting since the data in this study were collected. Although current reporting practices may be different, this analysis represents patients whose information is still present in the USRDS databases used by researchers, and the inaccuracies present in them must be considered, particularly among those missing cause of ESRD. The proportion of new ESRD patients with missing diagnoses on Form 2728 has decreased substantially over time (1), yet our results suggest that a large proportion of glomerular disease patients may still be missing a diagnosis code. Additional investigation of this discrepancy is needed in additional patient populations and in more recent data to detect changes in reporting which may have occurred over the past decade, and to investigate the generalizability of these results.

Research of glomerular diseases using USRDS data must consider the effect of these missing and misclassified diagnoses. In addition, research of nonglomerular diseases using Form 2728 data should consider the potential of misclassified glomerular disease patients labeled in other disease categories. Our results suggest that research of glomerular diseases in the USRDS database may be subject to substantial information bias, and those analyzing and interpreting USRDS data should be very aware of the potential misclassification. Additionally, physicians responsible for completing Form 2728 should be vigilant in ensuring they are accurate, realizing they provide valuable research opportunities for these devastating diseases.

Appendix 1.

Conversion table: Renal biopsy to Form 2728 classification

| n | Biopsy Finding | Form 2728 Diagnosis | Disease Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | Focal glomeruloscierosis, focal sclerosing GN | Glomerulonephritis |

| 3 | Tip lesion | Focal glomeruloscierosis, focal sclerosing GN | Glomerulonephritis |

| 6 | Collapsing glomerulonephritis | Focal glomeruloscierosis, focal sclerosing GN | Glomerulonephritis |

| 5 | C1Q | Focal glomeruloscierosis, focal sclerosing GN | Glomerulonephritis |

| 4 | Lupus membranous | Lupus erythematosus (SLE nephritis) | Secondary GN/vasculitis |

| 4 | Lupus nephritis | Lupus erythematosus (SLE nephritis) | Secondary GN/vasculitis |

| 22 | Diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis | Lupus erythematosus, (SLE nephritis) | Secondary GN/vasculitis |

| 27 | Membranous nephropathy | Membranous nephropathy | Glomerulonephritis |

| 9 | IgA nephropathy | IgA nephropathy, Berger disease | Glomerulonephritis |

| 2 | Sickle cell | Sickle cell disease/anemia | Miscellaneous conditions |

| 16 | AL amyloidosis | Amyloidosis | Neoplasms/tumors |

| 2 | Antiglomerular basement membrane disease | Goodpasture syndrome | Secondary GN/vasculitis |

| 7 | Light-chain deposition disease | Multiple myeloma | Neoplasms/tumors |

| 10 | Wegener granulomatosisa | Wegener granulomatosis | Secondary GN/vasculitis |

| 38 | Microscopic polyangiitisa | Vasculitis and its derivatives | Secondary GN/vasculitis |

| 30 | Renal-limited ANCA vasculitisa | Vasculitis and its derivatives | Secondary GN/vasculitis |

| 1 | Thin basement membrane | Hereditary/familial nephropathy | Cystic/hereditary/congenital diseases |

| 1 | Minimal change disease | Other renal disorders | Miscellaneous conditions |

| 6 | Fibrillary glomerulonephritis | Other renal disorders | Miscellaneous conditions |

Because of ANCA classification disagreements, another analysis was performed where all three of these categories were lumped together, and either a classification of Wegener or “Vasculitis and its derivatives” as considered a correct match.

Appendix 2.

Reported “primary cause of renal failure” codes on Medical Evidence Form 2728 for our sample

| ICD-9-CM Code | Description | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing | 124 | 57.1 | |

| 829A | Glomerulonephritis, not histologically examined | 19 | 8.8 |

| 4039D | Renal disease due to hypertension (no primary renal disease) | 13 | 6.0 |

| 5821A | Focal glomeruloscierosis, focal sclerosing GN | 11 | 5.1 |

| 4464B | Wegener granulomatosis | 8 | 3.7 |

| 5804B | Rapidly progressive GN | 8 | 3.7 |

| 7100E | Lupus erythematosus (SLE nephritis) | 8 | 3.7 |

| 5831A | Membranous nephropathy | 5 | 2.3 |

| 5820A | Other proliferative GN | 4 | 1.8 |

| 7999A | Etiology uncertain | 3 | 1.4 |

| 2773A | Amyloidosis | 2 | 0.9 |

| 4462A | Vasculitis and its derivatives | 2 | 0.9 |

| 2030A | Multiple myeloma | 2 | 0.9 |

| 58381B | IgA nephropathy, Berger disease (proof by immunofluorescence) | 2 | 0.9 |

| 0429A | AIDS nephropathy | 1 | 0.5 |

| 25000A | Type 2, adult-onset type or unspecified type diabetes | 1 | 0.5 |

| 5832A | Membranoproliferative GN type 1, diffuse MPGN | 1 | 0.5 |

| 5996A | Acquired obstructive | 1 | 0.5 |

| 7101B | Scieroderma | 1 | 0.5 |

| 75313A | Polycystic kidneys, adult type (dominant) | 1 | 0.5 |

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Drs. Vimal Derebail and JulieAnne McGregor for their assistance categorizing renal biopsy results into Form 2728 classifications.

Portions of this analysis were presented at the 2010 meeting of the Society for Epidemiologic Research; June 23 through 26, 2010; Seattle, WA.

The analyses upon which this publication is based were performed under contract no. 500-2006-NW006C entitled End Stage Renal Disease Networks Organization for the States of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, sponsored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The author assumes full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented. This article is a direct result of the Health Care Quality Improvement Program initiated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which has encouraged identification of quality improvement projects derived from analysis of patterns of care, and therefore required no special funding on the part of this contractor. Ideas and contributions to the author concerning experience in engaging with issues presented are welcomed.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “CMS 2728: What Good Is It?” on pages 1908–1909.

Access to UpToDate on-line is available for additional clinical information at http://www.cjasn.org/

References

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System: USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrayed AA, Shariff S, Maamari MMA: Kidney disease in Bahrain: A biopsy based epidemiologic study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant 18: 638–642, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyer O, Moulder JK, Somers MJG: Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis in children: A longitudinal assessment. Pediatr Nephrol 22: 1159–1166, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, Johnson RC, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Oleksyk T, McKenzie LM, Kajiyama H, Ahuja TS, Berns JS, Briggs W, Cho ME, Dart RA, Kimmel PL, Korbert SM, Michel DM, Mokrzycki MH, Schelling JR, Simon E, Trachtman H, Vlahov D, Winkler CA: MYH9 is a major-effect gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet 40: 1175–1184, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitiyakara C, Kopp JB, Eggers P: Trends in the epidemiology of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Semin Nephrol 23: 172–182, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cibrik DM, Kaplan B, Campbell DA, Kriesche HM: Renal allograft survival in transplant recipients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Transplat 3: 64–67, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins RM, Reynolds JC, Ahuja TS, Reid T, Agogoa LY, Bohen EM, Yuan CM, Abbott KC: Thrombotic microangiopathy in United States long-term dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 191–196, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong CS, Hingorani S, Gillen DL, Sherrard DJ, Watkins SL, Brandt JR, Ball A, Stehman-Breen CO: Hypoalbuminemia and risk of death in pediatric patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 61: 630–637, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chelamcharla M, Javaid B, Baird BC, Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS: The outcome of renal transplantation among systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 3623–3630, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds JC, Agodoa LY, Yuam CM, Abbott KC: Thrombotic microangiopathy after renal transplantation in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 1058–1068, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahuja TS, Abbott KC, Pack L, Kuo YF. HIV-associated nephropathy and end-stage renal disease in children in the United States. Pediatr Nephrol 19: 808–811, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longenecker JC, Coresh J, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Martin AA, Fink NE, Powe NR: Validation of comorbid conditions on the end-stage renal disease Medical Evidence Report: The CHOICE Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 520–529, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falk RJ, Hogan S, Carey TS, Jennette JC: The Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network: Clinical course of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated glomerulonephritis and systemic vasculitis. Ann Intern Med 113: 656–663, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dooley MA, Hogan S, Jennette JC, Falk R: Cyclophosphamide therapy for lupus nephritis: Poor renal survival in black Americans. Kidney Int 51: 1188–1195, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagnoux C, Hogan SL, Chin H, Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Guillevin L, Nachtman PH: Predictors of treatment resistance and relapse in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated small-vessel vasculitis: Comparison of two independent cohorts. Arthritis Rheum 58: 2908–2918, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson KL, Gipson DS, Massengill SA, Primack WA, Ferris MA, Hogan SL: Predictors of relapse and end stage kidney disease in proliferative lupus nephritis: Focus on children, adolescents, and young adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1962–1967, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gipson DS, Chin H, Prer TP, Jennette C, Ferris ME, Massengill S, Gibson K, Thomas DB: Differential risk of remission and ESRD in childhood FSGS. Pediatr Nephrol 21: 344–349, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogan SL, Satterly KK, Dooley MA, Nachman PH, Jennette JC, Falk RJ; Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network Silica exposure in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated glomerulonephritis and lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 134–142, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennette JC, Wieslander J, Tuttle R, Falk RJ: Serum IgA-fibronectin aggregates in patients with IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schönlein purpura: Diagnostic value and pathogenic implications. The Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network. Am J Kidney Dis 18: 466–471, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrussy K, Bacon PA, Churg J, Gross Wolfgang L, Hagen C, Hoffman GS, Hunder GG, Kallenberg CGM, McCluskey RT, Sinico RA, Rees AJ, Van Es LA, Waldherr R, Wiik A: Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides: Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum 37: 187–192, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Sorlie PD, Bell EM, Weitzman S, Smith JC, Folsom AR: Trends in the sensitivity, positive predictive value, false-positive rate, and comparability ratio of hospital discharge codes for acute myocardial infarction in four US communities, 1987–2000. Am J Epidemiol 160: 1137–1146, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Poole C, Lash TL: Causation and causal inference. In: Modern Epidemiology, 3rd ed., edited by Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL.Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008, pp 5–31 [Google Scholar]