Abstract

Background and objectives: Few elderly ESRD patients are ever wait-listed for deceased-donor transplantation (DDTX), and waiting list outcomes may not reflect access to transplantation in this group. Our objective was to determine longitudinal changes in access to transplantation among all elderly patients with ESRD, not just those wait-listed for DDTX.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Using data from the US Renal Data System, we determined changes in the adjusted likelihood of transplantation from any donor source as an indicator of access to transplantation among all incident ESRD patients aged 60 to 75 years between 1995 and 2006.

Results: Access to transplantation doubled between 1995 and 2006 despite an apparent decrease in the likelihood of DDTX after wait-listing. A threefold increase in the likelihood of living-donor transplantation, including a 1.5-fold increase in living-donor transplantation after wait-listing, was a key factor that led to increased access to transplantation. When a lead-time bias related to the increased practice of placing patients on the waiting list before dialysis initiation in more recent years was accounted for, there was no decrease in the likelihood of DDTX after wait-listing. The likelihood of receiving a DDTX after placement on the waiting list was maintained by a threefold increase in expanded-criteria-donor transplantation and a 26% reduction in the risk for death on the waiting list.

Conclusions: Although transplantation remains infrequent, elderly patients were twice as likely to undergo transplantation in 2006 versus 1995. Elderly patients with ESRD should not be dissuaded from pursuing transplantation.

Nearly half of a million individuals in the United States have ESRD, and 48% are aged ≥60 years (1). Even among this age group, kidney transplantation provides a significant survival advantage compared with treatment with dialysis (2). For example, the life expectancy of patients who have ESRD and are older than 60 years is nearly doubled with transplantation (3). During the past decade, the number of deceased and living organ donors in the United States has increased (1). Despite these advances, the relentless growth in the number of patients who are placed on the waiting list suggests that opportunities for transplantation have decreased over time, and the extent to which the increase in organ donation has kept pace with the growth in the elderly population with ESRD is unclear. Recently, it was reported that patients who are placed on the waiting list and are older than 60 years now have a nearly equal chance of death or transplantation from a deceased donor (4). These observations suggest the need to reconsider the appropriateness of deceased-donor transplantation (DDTX) in at least some subgroups of elderly patients; however, because only a fraction of elderly patients are ever placed on the waiting list, events on the waiting list may not accurately reflect access to transplantation in this patient age group (5).

In this analysis, we examine longitudinal changes in access to transplantation from any donor source among all incident patients who had ESRD and were aged ≥60 years in the United States between 1995 and 2006. Understanding how access to transplantation among the elderly has changed over time is necessary to ensure appropriate decision making regarding the use of transplantation in this population and should facilitate identification of opportunities to improve patient access to transplantation in the future.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study population included all incident patients who had ESRD (including incident dialysis and preemptive transplant recipients) who were between the ages of 60 and 75 years and were captured in the US Renal Data System between January 1995 and December 2006. The age range was chosen to capture elderly patients of transplantable age.

Study Design

We used the outcome of transplantation from any donor source among incident patients with ESRD as our primary metric of patient access to transplantation. The likelihood of transplantation from any donor source, by year of first ESRD treatment, was determined in univariate (Kaplan-Meier analyses) and multivariate (Cox regression) models. In these analyses, patients were followed from the date of first treatment for ESRD until the date of death, transplantation, or end of follow-up (September 30, 2007). Multivariate models incorporated recipient age, gender, race, cause of ESRD, body mass index (BMI), comorbid disease conditions (ischemic heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), ambulatory status, history of smoking or substance abuse, state-level rate of deceased organ donation per million population (6), median household income, and primary source of medical insurance as described previously (6,7).

Differences in access to transplantation between patient subgroups were determined by the use of interaction terms (year of ESRD incidence × patient subgroup). The following subgroups were examined: Recipient age (60 to 64.9, 65.0 to 69.9, and 70 to 74.9 years), race (white, black, and other), diabetes status, obese/nonobese (BMI < or ≥30), socioeconomic status (quartile of median household income), primary source of medical insurance, and state-level rate of deceased organ donation per million population. Similar models were constructed for transplantation from different donor sources, including (1) standard-criteria donors (SCDs; including neurologically brain dead and donation after circulatory death donors), (2) expanded-criteria donors (ECDs), and (3) living donors (LDs).

Statistical Analysis

To understand the processes underlying any change in access to transplantation over time, we also determined longitudinal changes in the likelihood of (1) placement on the deceased-donor waiting list, (2) preemptive transplantation from any donor source, (3) preemptive placement on the waiting list, (4) transplantation from a deceased donor after placement on the waiting list, (5) death on the waiting list, and (6) LD transplantation after placement on the deceased-donor waiting list using univariate and multivariate models as described already. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to model preemptive transplantation and placement on the waiting list. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Study Population and Characteristics

To provide an overview of the changes in the study population over time, we compared demographic and clinical characteristics between patients who initiated ESRD treatment during three equal time periods (1995 to 1998, 1999 to 2002, and 2003 to 2006; Table 1). Among the study patients, the proportion of male and obese patients was slightly higher in more recent years. Although there were statistically significant differences in the proportion of patients with a history of comorbid disease, smoking, substance abuse, and an inability to ambulate over time, these differences were relatively small.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population (N = 397,362) group by year of first treatment for ESRD

| Characteristic | 1995 to 1998 | 1999 to 2002 | 2003 to 2006 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 112,495 | 137,624 | 147,243 | |

| Age (years) | <0.0001 | |||

| 60.0 to 64.9 | 32,850 (29.2) | 40,926 (29.7) | 47,344 (32.1) | |

| 65.0 to 69.9 | 38,973 (34.6) | 46,507 (33.8) | 49,452 (33.6) | |

| 70.0 to 74.9 | 40,672 (36.2) | 50,191 (36.5) | 50,447 (34.3) | |

| Female | 55,740 (49.6) | 66,640 (48.4) | 68,511 (46.5) | <0.0001 |

| Race | 0.03 | |||

| black | 29,965 (26.6) | 36,143 (26.3) | 38,772 (26.3) | |

| white | 75,957 (67.5) | 93,087 (67.6) | 99,641 (67.7) | |

| other | 6573 (5.8) | 8394 (6.1) | 8830 (6.0) | |

| Cause of ESRD | <0.0001 | |||

| diabetes | 57,844 (51.4) | 73,731 (53.6) | 78,065 (53.0) | |

| GN | 8441 (7.5) | 8500 (6.2) | 7827 (5.3) | |

| other | 46,210 (41.1) | 55,393 (40.2) | 61,351 (41.7) | |

| BMI ≥30 | 19,800 (19.8) | 36,986 (28.1) | 48,671 (34.2) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbid disease | ||||

| IHD | 36,640 (32.6) | 45,988 (33.4) | 44,375 (30.1) | <0.0001 |

| cerebrovascular disease | 12,281 (10.9) | 15,364 (11.2) | 16,483 (11.2) | 0.06 |

| PVD | 20,361 (18.1) | 24,115 (17.5) | 25,391 (17.2) | <0.0001 |

| CHF | 42,752 (38.0) | 49,988 (36.3) | 53,607 (36.4) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 10,126 (9.0) | 13,049 (9.5) | 15,504 (10.5) | <0.0001 |

| Inability to ambulate or transfer | 5618 (5.0) | 6165 (4.5) | 9005 (6.1) | <0.0001 |

| History of smoking | 5605 (5.0) | 6088 (4.4) | 7564 (5.1) | <0.0001 |

| Substance abuse | 1559 (1.4) | 1596 (1.2) | 1987 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| State of residence grouped by deceased donation ratea | 0.0002 | |||

| Q1 | 13,890 (12.6) | 16,365 (12.2) | 17,501 (12.2) | |

| Q2 | 10,872 (9.9) | 13,416 (10.0) | 14,373 (10.0) | |

| Q3 | 33,922 (30.8) | 41,626 (30.9) | 44,440 (30.9) | |

| Q4 | 32,964 (29.9) | 40,839 (30.3) | 43,860 (30.5) | |

| Q5 | 18,589 (16.9) | 22,422 (16.7) | 23,549 (16.4) | |

| Median household incomeb | <0.0001 | |||

| $0 to $30,177 | 28,025 (25.7) | 33,315 (25.0) | 34,562 (24.4) | |

| $30,178 to $37,370 | 27,377 (25.1) | 33,260 (25.0) | 35,399 (25.0) | |

| $37,371 to $47,814 | 27,036 (24.8) | 33,184 (24.9) | 35,824 (25.3) | |

| >$47,814 | 26,729 (24.5) | 33,433 (25.1) | 35,984 (25.4) | |

| Insurer | <0.0001 | |||

| Medicare only | 41,193 (36.6) | 54,744 (39.8) | 63,543 (43.2) | |

| private only | 21,945 (19.5) | 24,810 (18.0) | 24,809 (16.9) | |

| both | 39,844 (35.4) | 49,450 (35.9) | 50,360 (34.2) | |

| neither | 9513 (8.5) | 8620 (6.3) | 8531 (5.8) |

Data are n (%). CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GN, glomerulonephritis; IHD, ischemic heart disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; Q, quintile.

Based on deceased organ donation rate per million population (6).

Determined using zip code of residence (7).

Change in Access to Transplantation from Any Donor Source over Time

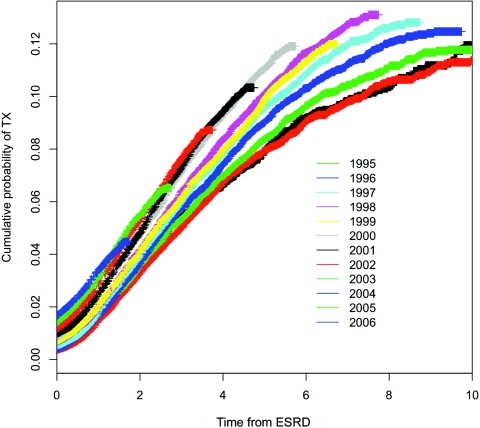

Figure 1 shows the improvement in the time to transplantation from any donor source over time. Despite this improvement, the cumulative probability of transplantation from any donor source at 1 and 3 years after first treatment for ESRD was still only 3.4% and 7.3% for the latest cohort of incident patients with adequate follow-up time to permit these calculations. In multivariate analyses, the adjusted likelihood of transplantation from any donor source among incident elderly patients in 2006 was double that among incident patients in 1995 (hazard ratio [HR] 2.01; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.85 to 2.19).

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of transplantation from any donor source by year of first ESRD treatment.

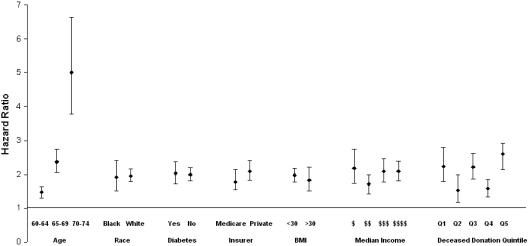

Figure 2 demonstrates that the adjusted likelihood of transplantation from any donor source in 2006 compared with 1995, varied by recipient age but not by race, diabetes status, socioeconomic status (median household income), BMI, or primary source of medical insurance or between patients who resided in states with different rates of deceased organ donation.

Figure 2.

Adjusted likelihood of transplantation from any donor source in 2006 compared with 1995 in different patient subgroups. The increased likelihood of transplantation from any donor source was consistently observed in a number of sociodemographic and clinical patient subgroups. The likelihood of transplantation in 2006 versus 1995 was significantly higher in patients who were 65 to 69 and 70 to 75 years compared with those who were aged 60 to 64 years. Deceased donation quintile (states were grouped into quintiles on the basis of rate of deceased donation per million population). $, 0 to 30,117; $$, 30,178 to 37,370; $$$, 37,371 to 47,814; $$$$, >47,418.

Longitudinal Changes in Transplantation from Deceased Donors and LDs

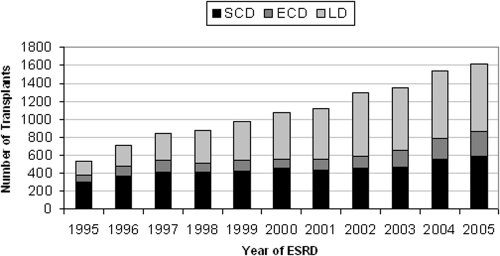

Figure 3 shows the number and type of transplants in study patients who developed renal failure in different calendar years during a uniform follow-up time of 2 years after the date of first ESRD treatment. The proportion of LD and ECD transplants was higher in patients who developed ESRD in more recent years.

Figure 3.

Number and type of transplants performed in study patients within 2 years of first treatment for ESRD, grouped by year of first ESRD treatment. The proportion of LD and ECD transplants was higher in more recent years.

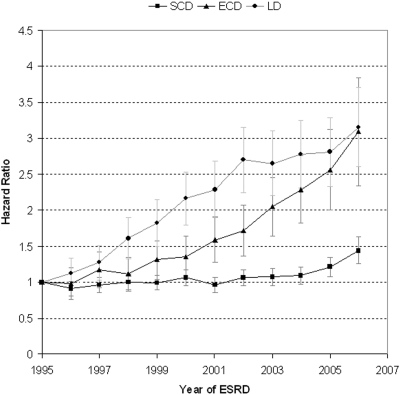

Figure 4 shows changes in the adjusted likelihood of transplantation from an SCD, ECD, and LD over time. There was no change in likelihood of transplantation from an SCD during the study period until after 2005. In contrast, the likelihood of ECD transplantation increased progressively during the study period, particularly after 2000. Similarly, the likelihood of LD transplantation increased markedly between the years 1995 and 2000 but remained relatively unchanged after 2000.

Figure 4.

Adjusted likelihood of SCD, ECD, and LD transplantation by year of first ESRD treatment. There was no change in likelihood of transplantation from an SCD during the study period until after 2005. In contrast, the likelihood of ECD transplantation increased progressively during the study period, particularly after 2000. Similarly, the likelihood of LD transplantation increased markedly between the years 1995 and 2000 but remained relatively unchanged after 2000.

Processes that Contribute to an Increase in Access to Transplantation over Time

The adjusted likelihood of placement on the waiting list increased each year during the study period (HR 2.16 [95% CI 2.04 to 2.30] in 2006 compared with 1995). There was evidence that transplantation was considered earlier in the disease course of elderly patients. Both preemptive transplantation (odds ratio 5.58 [95% CI 4.36 to 7.15] in 2006 compared with 1995) and placement on the deceased-donor waiting list before initiation of dialysis treatment (preemptive placement on the waiting list; OR 5.07 [95% CI 4.32 to 5.95] in 2006 compared with 1995) increased markedly during the study period. From the date of placement on the waiting list, the likelihood of transplantation from a deceased donor decreased over time (HR 0.66 [95% CI 0.58 to 0.76] in 2006 compared with 1995). To determine whether this decrease in DDTX after placement on the waiting list was related to more patients' being placed on the waiting list earlier in their course of chronic kidney disease in more recent years (e.g., preemptive listing), the likelihood of DDTX after placement on the waiting list was also determined in a second multivariate model, in which the time to DDTX among patients who were placed preemptively on the waiting list was determined from the date of first dialysis, rather than the date of preemptive placement on the waiting list. In this model, we found no change in the likelihood of DDTX among patients who were placed on the waiting list (HR 0.98 [95% CI 0.88 to 1.09] 2006 versus 1995); therefore, a lead-time bias related to increased preemptive placement on the waiting list in more recent years was the reason for the apparent decreased likelihood of DDTX in our model in which the time to DDTX was calculated from the date of placement on the waiting list.

The likelihood of obtaining an LD transplant after activation to the deceased-donor waiting list increased nearly 1.5-fold during the study period (HR 1.47 [95% CI 1.10 to 1.95] in 2006 compared with 1995). The likelihood of death on the waiting list decreased over time and was 0.74 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.91) in 2006 compared with 1995. To exclude the possibility that the observed longitudinal decrease in the risk for death on the waiting list was due to the delisting of very sick patients before death, we confirmed that there was no increase in death after delisting in more recent years (data not shown).

Discussion

Meeting the demand for solid-organ transplantation remains a daunting challenge in most countries. A comprehensive analysis of access to transplantation that includes all patients with ESRD, not just those who are on the waiting list for transplantation, is necessary for full understanding of the extent to which a health care system is meeting the need for transplantation (5). This may be particularly important in elderly patients and other groups who are infrequently placed on the waiting list (e.g., HIV-positive patients) (5). In these subgroups, an assessment of waiting list outcomes alone may provide a pessimistic and incomplete picture of access to transplantation, and patients and their physicians may inappropriately be dissuaded from pursuing transplantation as a treatment option.

Although the absolute number of elderly patients who access transplantation remains low, the increase in likelihood of transplantation over time across a broad range of sociodemographic and clinical patient subgroups should be considered a relative success of the transplant system in the United States. These findings demonstrate that the pursuit of transplantation in the elderly is not futile, and all patients without absolute medical contraindications should receive education regarding the benefits of transplantation and the various opportunities for transplantation that are available to them irrespective of their age.

Our analysis contradicts and extends the recent observations of Schold et al. (4), who reported that elderly patients who are placed on the waiting list have a near-equal chance of death or transplantation. That study reported that the likelihood of DDTX after placement on the waiting list among the elderly had decreased over time. Our analysis suggests that this finding may have been because patients are increasingly activated to the waiting list earlier in their disease course (preemptive listing) in more recent years. After accounting for this lead-time bias, we found no decrease in the likelihood of DDTX among patients who were on the waiting list.

Opportunities for DDTX among incident elderly patients with ESRD were maintained by the proliferation of ECD transplantation. During the study period, a number of events likely contributed to the increase in ECD transplantation, including formal implementation of the ECD program in October 2002, efforts of the transplant collaborative to increase deceased organ donations (8), and publication of information regarding the benefit of ECD transplantation in the elderly (9–11). Additional efforts to expand safely the use of ECDs and to ensure optimal use of these valuable organs are needed. In 2008, only 57.5% of recovered ECD kidneys were transplanted (12). Despite compelling evidence that ECD transplantation provides a survival benefit only in older adults, patients with diabetes, and registrants at centers with long waiting times, patients who will not benefit from ECD transplantation continue to be placed on the waiting list and undergo transplantation with these organs (13,14). Restricting the allocation of ECD kidneys only to patients who will derive a survival benefit from transplantation with these organs has been implemented in Eurotransplant and Canada and should similarly be adopted in the United States. Recent efforts to monitor the quality of transplant care at the transplant center level in the United States may paradoxically jeopardize future growth in the use of ECD transplantation in the elderly (15,16). Adjustment for case mix in these analyses is limited by the detail of donor and recipient information that is currently collected and available for analysis. The ECD designation, recipient age, and limited information regarding comorbid disease that is currently collected do not capture all facets of donor and recipient risk. Development and implementation of more sophisticated tools (17) to permit accurate assessment of center-specific outcomes is essential to ensuring the continued expansion of ECD transplantation in the elderly.

We also found a marked increase in the likelihood of LD transplantation. The growth in living donation indicates a willingness among elderly patients and their families to pursue this treatment option. Of potential concern, LD transplantation plateaued after 2000. Opportunities for LD transplantation in the elderly may be confined by the availability of potential donors. Elderly patients are more likely to have elderly potential donors. Elderly donors are more likely to have isolated medical abnormalities or lower levels of kidney function, and there is uncertainty about whether such individuals should donate (18,19). A very recent study (20) demonstrated that among a cohort of live kidney donors, mortality rate was not significantly increased compared with an age- and comorbidity-matched cohort. Additional studies to inform the risk of donation explicitly from elderly donors are important to expand living donation in the elderly. We also found that patients who were placed on the waiting list for DDTX increasingly obtained an LD transplant. This suggests the importance of the formal patient evaluation by transplant physicians in promoting live donation among patients and their families who do not initially consider this treatment option.

Although the likelihood of placement on the waiting list increased and risk for death on the waiting list decreased over time, the process of placing a patient on the waiting list remains a significant challenge in the elderly. Ensuring transplant readiness at all times may require frequent ongoing assessment of elderly transplant candidates (21). The associated work load and cost may deter programs from evaluating elderly patients and placing them on the waiting list. Adoption of predictable organ allocation algorithms that permit accurate determination of the timing of DDTX and increased placement of elderly patients on the ECD waiting list (which should decrease waiting times) should help to decrease the work load of wait list management in the elderly.

Readers of this study should consider the limitations of this retrospective registry-based analysis and that there is center-specific variation in the practice of transplant candidate evaluation in the United States. Ultimately, access to transplantation in any patient group is dependent on increased organ donation; however, reporting the longitudinal improvement in access to transplantation among the elderly is important to ensuring that this treatment option continues to be discussed and pursued in this age group.

Early engagement and education of patients and their families about the benefits and opportunities for transplantation may lead to further increases in the use of LD and ECD transplantation in this age group. Policy changes and research are also needed to expand further access to transplantation for the elderly. In summary, we found that access to transplantation among elderly patients with ESRD increased over time and believe that these patients should continue to be encouraged to pursue this treatment option.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

J.S.G. is funded by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research; and C.R. is funded by the Kidney Foundation of Canada, Western Regional Training Centre funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Endowment Fund.

The data reported here were supplied by the US Renal Data System.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

The views in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US government.

See related editorial, “Kidney Transplants for the Elderly: Hope or Hype?” on pages 1910–1911.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System: 2009 Annual Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL: Impact of cadaveric renal transplantation on survival in patients listed for transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1859–1865, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schold J, Srinivas TR, Sehgal AR, Meier-Kriesche HU: Half of kidney transplant candidates who are older than 60 years now placed on the waiting list will die before receiving a deceased-donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1239–1245, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill JS, Johnston O: Access to kidney transplantation: The limitations of our current understanding. J Nephrol 20: 501–506, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Renal Data System: 2005 Annual Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Rose C, Wiebe N, Gill J: Access to kidney transplantation among remote- and rural-dwelling patients with kidney failure in the United States. JAMA 301: 1681–1690, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Network for Organ Sharing: Expanded Criteria Donor Definition and Point System, Richmond, VA, United Network for Organ Sharing, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merion RM, Ashby VB, Wolfe RA, Distant DA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Metzger RA, Ojo AO, Port FK: Deceased-donor characteristics and the survival benefit of kidney transplantation. JAMA 294: 2726–2733, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schold JD, Meier-Kriesche HU: Which renal transplant candidates should accept marginal kidneys in exchange for a shorter waiting time on dialysis? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 532–538, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao PS, Merion RM, Ashby VB, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Kayler LK: Renal transplantation in elderly patients older than 70 years of age: Results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 83: 1069–1074, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.2008 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1998–2007. Rockville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill J, Rose CS, Johnston O, Mehrotra A, Gill JS: Allocation of ECD Kidneys in the US: How well are we following evidence based recommendations [Abstract]? Am J Transplant 10[Suppl 4]: 372, 2010. 19958323 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grams ME, Womer KL, Ugarte RM, Desai NM, Montgomery RA, Segev DL: Listing for expanded criteria donor kidneys in older adults and those with predicted benefit. Am J Transplant 10: 802–809, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abecassis MM, Burke R, Cosimi AB, Matas AJ, Merion RM, Millman D, Roberts JP, Klintmalm GB: Transplant center regulations: a mixed blessing? An ASTS Council viewpoint. Am J Transplant 8: 2496–2502, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Englesbe MJ, Ads Y, Cohn JA, Sonnenday CJ, Lynch R, Sung RS, Pelletier SJ, Birkmeyer JD, Punch JD: The effects of donor and recipient practices on transplant center finances. Am J Transplant 8: 586–592, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, Andreoni KA, Wolfe RA, Merion RM, Port FK, Sung RS: A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: The kidney donor risk index. Transplantation 88: 231–236, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neipp M, Jackobs S, Jaeger M, Schwarz A, Lueck R, Gwinner W, Becker T, Klempnauer J: Living kidney donors >60 years of age: Is it acceptable for the donor and the recipient? Transpl Int 19: 213–217, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Textor S, Taler S: Expanding criteria for living kidney donors: What are the limits? Transplant Rev (Orlando) 22: 187–191, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, Mehta SH, Singer AL, Taranto SE, McBride MA, Montgomery RA: Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA 303: 959–966, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danovitch GM, Hariharan S, Pirsch JD, Rush D, Roth D, Ramos E, Starling RC, Cangro C, Weir MR: Management of the waiting list for cadaveric kidney transplants: Report of a survey and recommendations by the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 528–535, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]