SYNOPSIS

Disease surveillance for hepatitis C in the United States is limited by the occult nature of many of these infections, the large volume of cases, and limited public health resources. Through a series of discrete processes, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health modified its surveillance system in an attempt to improve timeliness and completeness of reporting and case follow-up of hepatitis C. These processes included clinician-based reporting, electronic laboratory reporting, deployment of a Web-based disease surveillance system, automated triage of pertinent data, and automated character recognition software for case-report processing. These changes have resulted in an increase in the timeliness of reporting.

Surveillance for hepatitis C in the United States is limited and inconsistent.1–3 The reasons include a lack of clinical recognition of acute hepatitis C, the asymptomatic nature of chronic infection in more than 80% of those so affected, the lack of resources available for viral hepatitis surveillance, and the burden the quantity of reports can put on a health department's resources.2–4 In Massachusetts, a state with 6.4 million people, there are approximately 8,000 newly reported hepatitis C cases based on laboratory test results each year. Most individuals with positive test results have chronic hepatitis C, remotely acquired, and were never previously reported to the health department. Each reported case entails the receipt and processing of at least one laboratory report and one case-report form. However, multiple laboratory reports are frequently received on previously reported cases. Timely investigation of case reports is important in identifying potential acute infection and conducting appropriate public health follow-up. It also serves to identify demographic and risk characteristics, and determine geographic distribution. This information assists in resource allocation including targeting health education messages, and planning and providing health and support services.

During the last four years, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) instituted several changes to reporting requirements and the surveillance system for hepatitis C to expedite case finding and enhance data capture. This article details enhancements to the Massachusetts hepatitis C surveillance system, implemented between 2004 and 2007, and the impacts of these modifications on timeliness and completeness of reporting.

METHODS

MDPH case ascertainment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection begins with the receipt of a positive laboratory report for HCV infection. Laboratory data are received in both paper and electronic laboratory reporting formats. Acceptable laboratory reports include anti-HCV antibody tests (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and recombinant immunoblot assay), and nucleic acid tests (HCV-ribonucleic acid tests, viral load, and viral genotyping). A case of hepatitis C infection is referred to as a disease “event.”

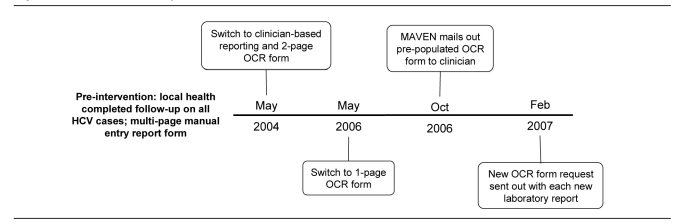

We selected the period 2001–2008 to provide three years of comparison on either side of the first surveillance intervention, as well as a full year of data following the final intervention in 2007. Figure 1 provides a timeline of the interventions that are described in this article. We defined an event date as the earliest available date of case ascertainment, symptom onset, or laboratory specimen collection or diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Massachusetts hepatitis C surveillance timeline: 2004–2007

OCR = optical character recognition

MAVEN = Massachusetts Virtual Epidemiologic Network

HCV = hepatitis C virus

We calculated monthly response rate as the number of completed forms received by MDPH over the number of forms mailed out by MDPH. This figure can only be calculated from late 2006 onward, as the date a form was mailed out was not captured until November 2006. To measure completeness, we evaluated forms using risk factor information. Forms were considered complete if at least one risk factor, of the 10 asked about on the case-report form, had an answer provided. Alternatively, the forms were grouped as having all risk factors marked as “unknown” or all risk factor questions left blank. We calculated timeliness as the difference between the date the HCV event was created in the Massachusetts Virtual Epidemiologic Network (MAVEN) and the date a completed optical character recognition (OCR) form was received at MDPH.

Pre-intervention

In Massachusetts, primary responsibility for completing investigations of most reportable diseases falls to the local board of health or health department within 351 cities and towns. These local public health authorities vary in their capacity for follow-up; many are staffed by one or fewer full-time public health nurses or health agents. For hepatitis C infections, local health departments (LHDs) previously had responsibility to complete follow-up on each patient, which often involved communicating with the patient's primary health-care provider and the patient, and then completing a case-report form. This completed case-report form was returned to the MDPH and reviewed by an epidemiologist to assign appropriate surveillance classification status. For HCV infection, this report form was four pages long and took approximately five to seven minutes to complete.

Intervention 1

In May 2004, when the increasing volume of reports placed too high a burden on LHDs, responsibility for completing requests on HCV-infected cases shifted to health-care providers, specifically the ordering provider, who most likely would have relevant information about the case. The form that was developed for this process was a two-page OCR form that allowed for automated forms processing via a computer scanning program called TeleForm®.5 Upon receipt of a positive hepatitis C laboratory report, the ordering provider name, as well as patient name and available demographic information (e.g., address, date of birth or age, gender, and race), were entered into a Microsoft® Access database. The ordering provider's mailing information was obtained from the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine, and the OCR form—pre-populated with the patient name and address—was sent. If the ordering provider's name was not available, the OCR form was sent to the infection preventionist of a reporting facility for completion.

With the implementation of this new reporting requirement, an educational mailing was sent to health-care providers, introducing them to the new reporting form and the process for reporting HCV infection events to MDPH.

The TeleForm database is a stand-alone system developed for automated forms processing. All data captured on the OCR form were stored in this database. Any forms received by mail were manually scanned into the TeleForm database; forms received by fax were sent directly into the database via a fax server, so it was not necessary to print the document. An electronic image was retained in case it was necessary to review the form at a later date. Data entry staff verified all scanned forms to catch any errors that might have occurred during the scanning process. Verification of these forms took approximately two to three minutes. Information on potential acute hepatitis C infection was captured on a longer case-report form that was processed manually.

The TeleForm database was not linked to the database that housed the patient information. Epidemiologists reviewed the scanned and verified OCR forms in the TeleForm system and assigned a classification status based on the laboratory data provided, without the benefit of additional data contained in the Access database. On a quarterly basis, the Access database was updated with the surveillance classification status and form receipt variables from the TeleForm system.

Intervention 2

On May 1, 2006, the OCR form was modified further to collect all necessary information on one page, still using the automated forms processing format. This change was made after numerous issues were identified with a two-page form, including data loss, because only one of the two pages was returned.

Intervention 3

On October 1, 2006, MDPH began using a Web-based disease surveillance system for tracking and investigating most reportable infectious diseases in the state. This system, MAVEN, automatically mailed HCV OCR forms to the providers ordering tests that were indicative of HCV infection. This system also allows for the complete capture of all event information, including laboratory, demographic, risk, and clinical information. More robust laboratory data are collected and electronic messages can be received with clinical and laboratory data through electronic messaging formats such as Health Level Seven International (HL7). MAVEN also allows for multiple automated mailings for disease events and multiple providers.

The process for investigating newly reported HCV events was similar to the process described and instituted in Intervention 1. With MAVEN in place, however, the process was automated. Newly reported HCV events populated a “workflow” in MAVEN. A workflow is designed to capture relevant events based on a predetermined set of entry and exit criteria. For the HCV workflow, entry required a provider name or a facility to be indicated in the laboratory report. The process for determining the provider name and address was the same as described for Intervention 1. Events were opened from the workflow and the pre-populated OCR form was printed for mailing. The event exited the workflow once the OCR form mail-out date was populated.

Data from returned completed forms were transferred automatically from the TeleForm database into MAVEN on a daily basis using the HL7 messaging format. Once data were in MAVEN, an epidemiologist was able to review the case in its entirety, including demographic, clinical, laboratory, and risk information, and then assign a surveillance case classification status.

Intervention 4

Due to low response rates from ordering providers and infection preventionists, a further change was implemented on February 1, 2007. This change involved programming MAVEN to send a new OCR form to the ordering provider each time a positive laboratory result was received on existing cases, no matter how many times that occurred, until a completed OCR was returned on that particular case. By mailing out requests for form completion with each new laboratory report and provider, MDPH is able to find the provider with the most information on the case. For example, if the first time the patient is tested is in an emergency department, that provider is less likely to complete the reporting form. If, however, the patient visits his or her primary care provider and follow-up testing is performed, MDPH will receive that laboratory report and connect with the patient's primary care provider.

New laboratory reports are regularly received by MDPH for events reported several years prior. This means that events with event dates prior to this new intervention period had new form requests sent out as a result of this newest intervention. For example, if a new laboratory report was received on February 2, 2007, for a case of hepatitis C originally reported in 2004, and a case-report form had not previously been received, MAVEN would send out a new request for form completion for that 2004 event. Thus, starting in February 2007, events with dates prior to the intervention period were being processed by MAVEN with new form completion requests, in addition to newly reported HCV events.

RESULTS

Completeness

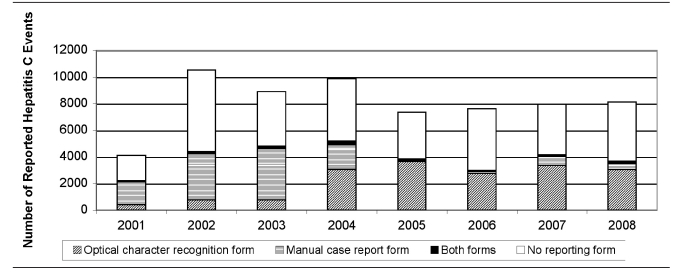

The OCR form was put into use in 2004. From 2005 to 2008, a total of 31,025 new HCV events were reported, of which 13,191 (43%) had a completed OCR form. For the years prior to the implementation of the OCR form (2001–2003), 40% of HCV events had a manual case-report form completed (9,488 of 23,521). Because an OCR form is now sent out with each new laboratory report regardless of event date (due to the change initiated in February 2007 described in Intervention 4), 4,983 HCV events dated before 2005 had case information submitted via an OCR form, but not a multipage manual case-report form. Figure 2 displays HCV events by report form submitted. Overall, completed OCR forms were received for 27% of all reported HCV events (18,849 of 69,171, with OCR forms sent for multiple events per case), with event dates between 2001 and 2008.

Figure 2.

Hepatitis C events reported in Massachusetts, by year and surveillance form type

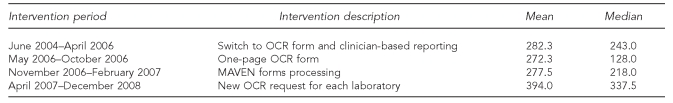

The mean number of forms received on a monthly basis remained relatively stable until the final intervention in February 2007. The Table provides a breakdown of the mean and median numbers of forms received per month, by intervention period. The minimum number of forms received in a month was in June 2006, with 21 forms; the maximum number of forms received was in June 2008, with 733 completed forms. Since Intervention 4 in February 2007, MDPH has sent out a mean of 1,031 form completion requests a month (median = 862). The mean and median response rates for these requests since February 2007 have been 43% and 44%, respectively.

Since the first intervention implemented in 2005, 1,450 HCV events were reported via the original multipage manual case-report form, 12,810 HCV events were reported through an OCR form, and 381 HCV events were reported on both OCR and manual case-report forms. On OCR forms, 75% (n=9,649) had at least one risk factor response, 16% (n=1,988) had all risk variables marked as “unknown,” and 9% (n=1,173) had all risk factors blank. In comparison, 64% (n=926) of completed manual case-report forms had at least one risk factor variable completed, 7% (n=108) had all risk factors marked as “unknown,” and 29% (n=416) were missing values for all risk factors.

The OCR form was reduced from a two-page form to a one-page form on May 1, 2006. Before May 2006, 6,493 OCR forms were received (271 per month); after May 2006, 10,799 OCR forms were received (337 per month). With the two-page form, 76% had at least one risk factor variable completed, 14% had all risk factor questions answered with “unknown,” and 10% of the forms were missing all risk factor data. Since the introduction of the one-page form, 81% had at least one risk factor variable completed, 16% had all risk factor questions answered with “unknown,” and 3% of the forms were missing all risk factor data.

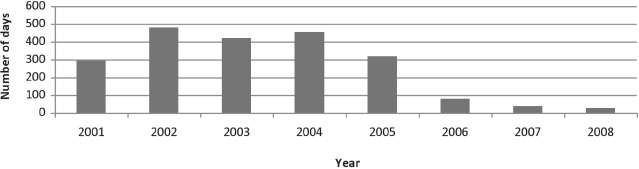

Timeliness

The median and mean reporting times decreased since the interventions were implemented. Median reporting times are displayed in Figure 3. The median reporting time for all types of report forms dropped from 454 days in 2004 (when the two-page OCR form was being used) to 26 days in 2008; the mean reporting time for the single-page OCR form dropped from a maximum of 393 days in 2004 to 50 days in 2008.

Figure 3.

Median time to receipt of hepatitis C optical character recognition case-report form in Massachusetts, 2001–2008

DISCUSSION

The MDPH surveillance system for HCV infection has undergone several transformations in the last five years that allowed data capture on more cases, in a much more timely fashion. Adoption of all or some of these measures by other health departments may improve the collection of more timely and complete information on a disease that places a burden on surveillance resources.

The TeleForm system allows for rapid data entry, although there may be trade-offs in terms of cost and accuracy.6–8 However, given that MDPH has approximately 8,000 new HCV events reported each year, the ability to enter large amounts of information quickly is desirable. A standard multipage case-report form generally takes 10–20 minutes to complete; an OCR form takes approximately two to three minutes to scan and verify. Other measures to enhance timeliness include the electronic transfer of results from laboratories.9–11 MDPH is also exploring direct transfer from electronic medical records as a way to further enhance timeliness and completeness.3,12–14

The transition from LHDs completing follow-up to provider-based reporting has increased efficiency, as providers have direct access to patient information and potentially risk history. They are able to complete the OCR form quickly and with minimal effort given that it is a one-page form. By mailing out requests for form completion with each new laboratory report and provider, MDPH is able to find the provider with the most information on the case. The improved targeting of clinicians has reduced the time it takes to receive a completed form.

CONCLUSIONS

Although MAVEN has allowed for multiple form send-outs and returns, completeness of reports remains an issue, as it has always been with conventional reporting systems.6,15 The proportion of forms with no risk information has remained relatively constant. Risk information is critical for disease prevention and program planning. There is a need for further outreach to clinicians and education about the importance of submitting this information, as well as the collection of risk information in the first place.

Table 1.

Mean and median number of hepatitis C surveillance forms received per month in Massachusetts: 2004–2008

OCR = optical character recognition

MAVEN = Massachusetts Virtual Epidemiologic Network

REFERENCES

- 1.Fleming DT, Zambrowski A, Fong F, Lombard A, Mercedes L, Miller C, et al. Surveillance programs for chronic viral hepatitis in three health departments. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:23–35. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klevens RM, Miller J, Vonderwahl C, Speers S, Alelis K, Sweet K, et al. Population-based surveillance for hepatitis C virus, United States, 2006–2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1499–502. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.081050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and liver cancer: a national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR-19):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.TeleForm®: Version 9.1. San Francisco: Autonomy; 1992. Autonomy. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jorgensen CK, Karlsmose B. Validation of automated forms processing. A comparison of Teleform with manual data entry. Comput Biol Med. 1998;28:659–67. doi: 10.1016/s0010-4825(98)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quan KH, Vigano A, Fainsinger RL. Evaluation of a data collection tool (TELEform) for palliative care research. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:401–8. doi: 10.1089/109662103322144718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doherty S, Davis L, Leschke P, Valpiani A, Whitely E, Yarnold D, et al. Automated versus manual audit in the emergency department. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2008;21:671–8. doi: 10.1108/09526860810910140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Effler P, Ching-Lee M, Bogard A, Ieong MC, Nekomoto T, Jernigan D. Statewide system of electronic notifiable disease reporting from clinical laboratories: comparing automated reporting with conventional methods [published erratum appears in JAMA 2000;283:2937] JAMA. 1999;282:1845–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.19.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panackal AA, M'Ikanatha NM, Tsui FC, McMahon J, Wagner MM, Dixon BW, et al. Automatic electronic laboratory-based reporting of notifiable infectious diseases at a large health system. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:685–91. doi: 10.3201/eid0807.010493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overhage JM, Grannis S, McDonald CJ. A comparison of the completeness and timeliness of automated electronic laboratory reporting and spontaneous reporting of notifiable conditions. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:344–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klompas M, Haney G, Church D, Lazarus R, Hou X, Platt R. Automated identification of acute hepatitis B using electronic medical record data to facilitate public health surveillance. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Automated detection and reporting of notifiable diseases using electronic medical records versus passive surveillance— Massachusetts, June 2006–July 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(14):373–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus R, Klompas M, Campion FX, McNabb SJ, Hou X, Daniel J, et al. Electronic support for public health: validated case finding and reporting for notifiable diseases using electronic medical data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:18–24. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jajosky RA, Groseclose SL. Evaluation of reporting timeliness of public health surveillance systems for infectious diseases. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]