SYNOPSIS

Objectives

We provided national prevalence estimates for selected health-risk behaviors for Asian American and Pacific Islander high school students separately, and compared those prevalence estimates with those of white, black, and Hispanic students.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. To generate a sufficient sample of Asian American and Pacific Islander students, we combined data from four nationally representative surveys of U.S. high school students conducted in 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2007 (total n=56,773).

Results

Asian American students were significantly less likely than Pacific Islander, white, black, or Hispanic students to have drunk alcohol or used marijuana. Asian American students also were the least likely to have carried a weapon, to have been in a physical fight, to have ever had sexual intercourse, or to be currently sexually active. Once sexually active, Asian American students were as likely as most other racial/ethnic groups to have used alcohol or drugs at last sexual intercourse or to have used a condom at last sexual intercourse. Pacific Islander students were significantly more likely than Asian American, white, black, or Hispanic students to have seriously considered or attempted suicide.

Conclusions

The prevalence estimates of health-risk behaviors exhibited by Asian American students and Pacific Islander students are very different and should be reported separately whenever feasible. To address the different health-risk behaviors exhibited by Asian American and Pacific Islander students, prevention programs should use culturally sensitive strategies and materials.

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are among the fastest-growing racial/ethnic groups in the United States.1,2 Their numbers are expected to rise from 12 million in 2000 to 43 million in 2050, when they will comprise approximately 10% of the U.S. population.2,3 Geographically, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are concentrated in the West and Northeast. Approximately half live in three states: California, New York, and Hawaii.1,2

“Asian” refers to those having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent.4 Asian Americans represent about 4.2% of the total U.S. population.5 The largest subgroups of Asian Americans are Chinese (24%), Filipino (18%), Asian Indian (16%), Vietnamese (11%), Korean (10%), and Japanese (8%).5 “Pacific Islander” refers to those having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.4 Pacific Islanders represent about 0.3% of the total U.S. population.6 The largest subgroups of Pacific Islanders are Native Hawaiian (37%), Samoan (22%), Guamanian (15%), Tongan (7%), Fijian (3%), and Marshallese (2%).6 The Asian and Pacific Islander population is not a homogeneous group; rather, it comprises many groups who differ in language, culture, and length of residence in the U.S. Approximately 26% of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are younger than age 18.4

As the Asian American and Pacific Islander populations grow, the public health impact of their health behaviors will become increasingly important. This is especially true among adolescents, because health-risk behaviors are often established during childhood and adolescence and extend into adulthood. Although Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are often portrayed as “model minorities,” large variations in health disparities and risk behaviors have been observed among different subgroups.1,7 Because many Asian American and Pacific Islanders were born in other countries, their health outcomes and behaviors are often influenced by issues of nativity, attachment to values held in the culture of origin, and the process of acculturation. For example, in a study of family obligation attitudes and behaviors and depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents, foreign-born adolescents reported higher levels of family obligation behavior than their U.S.-born counterparts. Findings also suggested that higher levels of family obligation were associated with fewer depressive symptoms.8

Unfortunately, because of the small numbers of Asian American and Pacific Islander youth found in most public health surveillance and data systems, relatively little is known about their health behaviors. National studies describing the prevalence of priority health-risk behaviors among adolescents typically present data for white, black, and Hispanic young people, but not Asian American and Pacific Islander young people.9–13 Other studies present data for Asian American and Pacific Islander young people combined in a single category or present data only for Asian American young people, possibly obscuring important differences.14–19

The purpose of this study was to provide national prevalence estimates for selected health-risk behaviors for Asian American and Pacific Islander students separately in four major categories: substance use, sexual behaviors, violence and unintentional injury, and chronic disease-related behaviors. We also compared these prevalence estimates with those of white, black, and Hispanic students. Finally, we examined racial/ethnic variations in the co-occurrence of multiple health-risk behaviors.

METHODS

Sample and survey administration

The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System was implemented in 1990 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to monitor priority health-risk behaviors among young people over time. The national school-based Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) has been conducted biennially since 1991. Each survey year, a similar three-stage cluster sample design was used to obtain a nationally representative sample of public and private school students in grades nine through 12 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. To generate a sufficient sample of Asian American and Pacific Islander students, we combined data from four national YRBSs conducted in 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2007. Sampling strategies and the psychometric properties of the questionnaire have been reported previously.12,20,21

Student participation in the survey was anonymous and voluntary, and local parental permission procedures were followed. The CDC Institutional Review Board granted approval for the national YRBS. Students completed the self-administered questionnaire during a regular class period. Responses were recorded directly on computer-scannable questionnaire booklets. In 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2007, school response rates were 75%, 81%, 78%, and 81%, respectively; student response rates were 83%, 83%, 86%, and 84%, respectively; overall response rates were 63%, 67%, 67%, and 68%, respectively; and sample sizes were 13,601; 15,214; 13,917; and 14,041, respectively.12,22–24 A weighting factor was applied to each record to adjust for nonresponse and the oversampling of black and Hispanic students.

Measures

We selected five health-risk behaviors in each of four categories: substance use, sexual behaviors, violence and unintentional injury, and chronic disease-related behaviors. The risk behaviors selected are important predictors of key public health outcomes.

Substance use behaviors included current cigarette use, current smokeless tobacco use, current alcohol use, episodic heavy drinking, and current marijuana use. Sexual behaviors included ever having had sexual intercourse, ever having had sexual intercourse with four or more people during their lifetime, currently sexually active, drank alcohol or used drugs before last sexual intercourse, and condom use.

Violence and unintentional injury behaviors included carried a weapon, in a physical fight, seriously considered attempting suicide, attempted suicide, and rarely or never wore a seat belt. Chronic disease-related behaviors included regular participation in vigorous physical activity, regular participation in moderate physical activity, ate fruit and vegetables five or more times per day, drank three or more glasses of milk per day, and obese based on body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile compared with gender- and age-specific reference data from CDC growth charts.25

Finally, to examine racial/ethnic variations in the co-occurrence of multiple health-risk behaviors, we created a multiple risk behavior variable by selecting 12 behaviors that applied to all students and represented the risk behavior categories equally (i.e., three behaviors from each category). Complete descriptions of individual risk behaviors and the multiple risk behavior variable are provided in Tables 1–5.

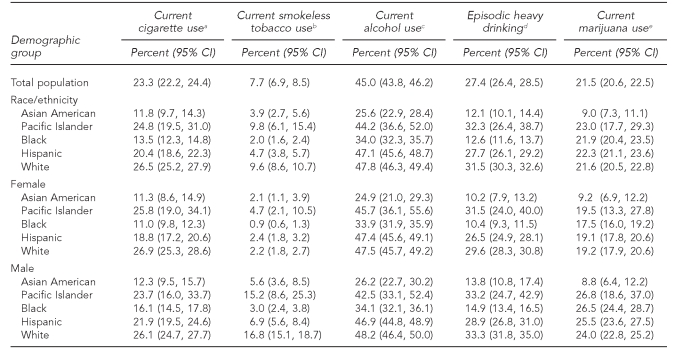

Table 1.

Prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use among high school students, by race/ethnicity and gender—U.S., 2001–2007

aSmoked cigarettes on at least one day during the 30 days before the survey

bUsed chewing tobacco, snuff, or dip on at least one day during the 30 days before the survey

cHad at least one drink of alcohol on at least one day during the 30 days before the survey

dHad five or more drinks of alcohol in a row; that is, within a couple of hours on at least one day during the 30 days before the survey

eUsed marijuana one or more times during the 30 days before the survey

CI = confidence interval

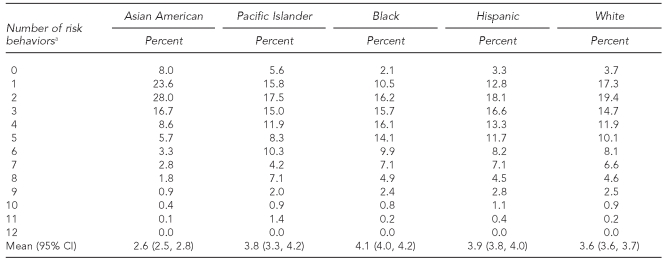

Table 5.

Prevalence of engaging in multiple health-risk behaviors and mean number of risk behaviors among high school students, by race/ethnicity—U.S., 2001–2007

aSelected risk behaviors included:

● Smoked cigarettes on at least one day during the 30 days before the survey

● Had at least one drink of alcohol on at least one day during the 30 days before the survey

● Used marijuana one or more times during the 30 days before the survey

● Ever had sexual intercourse

● Had sexual intercourse with four or more people during their lifetime

● Had sexual intercourse with at least one person during the three months before the survey

● In a physical fight one or more times during the 12 months before the survey

● Seriously considered attempting suicide during the 12 months before the survey

● Rarely or never wore a seat belt when riding in a car driven by someone else

● Participated in exercise or physical activities that made students sweat and breathe hard for at least 20 minutes on fewer than three of the seven days before the survey

● Ate fruit and vegetables fewer than five times per day during the seven days before the survey

● Obese, based on self-reported height and weight, body mass index = weight [kilograms]/height [meters squared] ≥95th percentile using growth charts developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for young people aged 2–20 years

CI = confidence interval

Race was assessed using the following question: “What is your race? (Select one or more responses.)” Response options were American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and white. Ethnicity was assessed with a yes or no answer to the following question: “Are you Hispanic or Latino?” Based on self-report of race and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, we defined five categories of race/ethnicity: (1) Asian, non-Hispanic (hereafter, Asian American); (2) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic (hereafter, Pacific Islander); (3) white, non-Hispanic (hereafter, white); (4) black or African American, non-Hispanic (hereafter, black); and (5) Hispanic or Latino, irrespective of race or races selected (hereafter, Hispanic). American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic and multiracial (i.e., selected more than one race) non-Hispanic students were excluded from the analysis.

Analysis

We calculated prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for high school students overall and for each of the five racial/ethnic subgroups. Data from students of other racial/ethnic groups and students who did not provide racial/ethnic information were included in total population estimates but were not presented separately. To account for the complex sample design of the survey, we conducted all analyses on weighted data using SUDAAN®.26 As racial/ethnic differences in health-risk behaviors sometimes vary by gender, we also calculated prevalence estimates separately for male and female students.12 Finally, we examined the frequency distribution of multiple health-risk behaviors as well as the mean number of risk behaviors by race/ethnicity. We determined pairwise differences in prevalence estimates and mean number of risk behaviors by race/ethnicity using t-tests. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05. Only statistically significant differences were reported in the results.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The total sample size for the combined 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2007 national YRBS was 56,773 and included 3.4% Asian American (n=1,599), 0.8% Pacific Islander (n=409), 14.1% black (n=12,482), 15.2% Hispanic (n=14,352), 62.7% white (n=24,818), and 3.7% other racial/ethnic minorities (n=2,316). Gender and age distributions were similar among racial/ethnic groups; the proportion of female students ranged from 47.2% among Asian American students to 51.8% among Pacific Islander students, and the mean age ranged from 15.9 years among Hispanic students to 16.1 years among white students.

Substance use behaviors

Overall and among females, the prevalence of current cigarette use was higher among Pacific Islander, white, and Hispanic students than among Asian American and black students, and it was higher among white students than among Hispanic students (Table 1). Among males, the prevalence was higher among Pacific Islander, white, black, and Hispanic students than among Asian American students, and it was higher among white students than among black and Hispanic students.

Overall and among males, the prevalence of current smokeless tobacco use was highest among Pacific Islander and white students, lower among Asian American and Hispanic students, and lowest among black students (Table 1). Among females, smokeless tobacco use was uncommon and did not vary by race/ethnicity, except that the prevalence was higher among white and Hispanic students than among black students.

Overall and among females, the prevalence of current alcohol use was highest among Pacific Islander, white, and Hispanic students; lower among black students; and lowest among Asian American students (Table 1). Among males, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence among Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from black students.

Overall, among females and males, the prevalence of episodic heavy drinking was higher among Pacific Islander, white, and Hispanic students than among Asian American and black students (Table 1). The pattern was the same for current marijuana use, except that the prevalence of this behavior was higher among black students than among Asian American students.

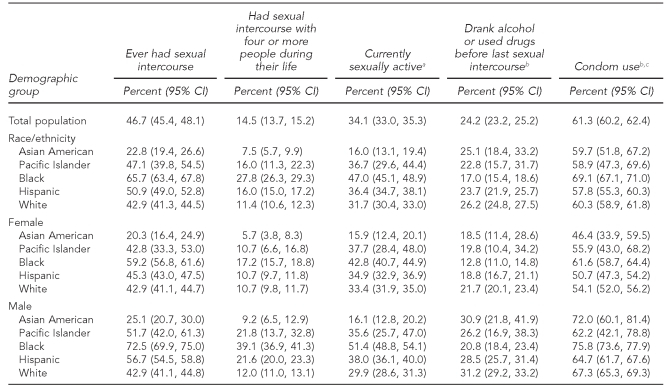

Sexual behaviors

Overall, the prevalence of ever having had sexual intercourse, having had sexual intercourse with four or more people during their lifetime, and being currently sexually active was highest among black students; lower among Pacific Islander, white, and Hispanic students; and lowest among Asian American students (Table 2). Among females, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence of multiple sexual partners did not vary significantly between Pacific Islander and Asian American students and the prevalence of being currently sexually active did not vary significantly between Pacific Islander and black students. Among males, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence of multiple sexual partners did not vary significantly between white and Asian American students.

Table 2.

Prevalence of sexual behaviors among high school students, by race/ethnicity and gender—U.S., 2001–2007

aHad sexual intercourse with at least one person during the three months before the survey

bAmong students who were currently sexually active

cUsed a condom during last sexual intercourse

CI = confidence interval

Overall, among those who were currently sexually active, the prevalence of having drunk alcohol or used drugs before last sexual intercourse was higher among Asian American, white, and Hispanic students than among black students (Table 2). The prevalence among Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from other racial/ethnic groups. Among both currently sexually active females and males, the prevalence among Asian American and Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from other racial/ethnic groups.

Of students who were currently sexually active, overall and among females, the prevalence of having used a condom during last sexual intercourse was lower among Asian American, white, and Hispanic students than among black students (Table 2). The prevalence among Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from other racial/ethnic groups. Among currently sexually active males, the prevalence among Asian American and Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from other racial/ethnic groups, and the prevalence was lower among white and Hispanic students than among black students.

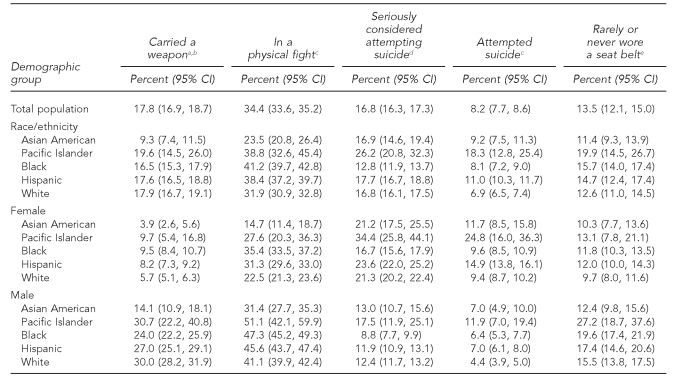

Violence and unintentional injury behaviors

Overall, among females and males, the prevalence of having carried a weapon was higher among Pacific Islander, white, black, and Hispanic students than among Asian American students (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of behaviors that contribute to violence and unintentional injury among high school students, by race/ethnicity and gender—U.S., 2001–2007

aFor example, a gun, knife, or club

bOn at least one day during the 30 days before the survey

cOne or more times during the 12 months before the survey

dDuring the 12 months before the survey

eWhen riding in a car driven by someone else

CI = confidence interval

Overall and among males, the prevalence of having been in a physical fight was higher among black and Hispanic students, lower among white students, and lowest among Asian American students (Table 3). The prevalence among Pacific Islander students was higher than among Asian American and white students, but it did not vary significantly from black and Hispanic students. Among females, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence among Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from white students.

Overall and among females, the prevalence of having seriously considered attempting suicide was highest among Pacific Islander students; lower among Asian American, white, and Hispanic students; and lowest among black students (Table 3). Among males, the prevalence was higher among Pacific Islander, Asian American, white, and Hispanic students than among black students.

Overall, the prevalence of having attempted suicide was highest among Pacific Islander students; lower among Asian American, black, and Hispanic students; and lowest among white students (Table 3). Among females, the prevalence was higher among Pacific Islander students than among Asian American, white, and black students. Among males, the prevalence was higher among Asian American, Pacific Islander, black, and Hispanic students than among white students.

Overall, the prevalence of rarely or never wearing a seat belt was higher among Pacific Islander and black students than among Asian American and white students (Table 3). The prevalence was higher among Hispanic students than among Asian American students. Among females, the prevalence did not vary by race/ethnicity. Among males, the prevalence was higher among Pacific Islander students, lower among white and Hispanic students, and lowest among Asian American students. The prevalence among black males was higher than among Asian American and white males.

Chronic disease-related behaviors

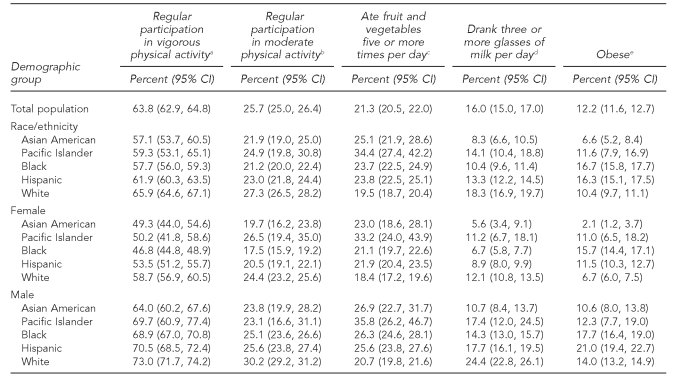

Overall and among females, the prevalence of regular participation in vigorous physical activity was lower among Asian American, Pacific Islander, black, and Hispanic students than among white students (Table 4). Among males, the prevalence was lower among Asian American students, higher among black and Hispanic students, and highest among white students. The prevalence among Pacific Islander males did not vary significantly from males in other racial/ethnic groups.

Table 4.

Prevalence of participation in vigorous and moderate physical activity; consumption of fruit, vegetables, and milk; and obesity among high school students, by race/ethnicity and gender—U.S., 2001–2007

aParticipated in exercise or physical activities that made students sweat and breathe hard for at least 20 minutes on three or more of the seven days before the survey

bParticipated in physical activities that did not make students sweat or breathe hard for at least 30 minutes on five or more of the seven days before the survey

cDrank 100% fruit juice, or ate fruit, green salad, potatoes (excluding French fries, fried potatoes, or potato chips), carrots, or other vegetables five or more times per day during the seven days before the survey

dDrank three or more glasses of milk per day during the seven days before the survey

eBased on self-reported height and weight, body mass index = weight [kilograms]/height [meters squared]) ≥95th percentile using growth charts developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for young people aged 2–20 years

CI = confidence interval

Overall and among males, the prevalence of regular participation in moderate physical activity was lower among Asian American, black, and Hispanic students than among white students (Table 4). The prevalence among Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from other racial/ethnic groups. Among females, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence among Pacific Islander students was higher than among black students.

Overall, the prevalence of eating fruit and vegetables five or more times per day was lowest among white students; higher among Asian American, black, and Hispanic students; and highest among Pacific Islander students (Table 4). Among females, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence among Asian American students did not vary significantly from other racial/ethnic groups. Among males, the prevalence was lower among white students than among Asian American, Pacific Islander, black, and Hispanic students.

Overall, the prevalence of drinking three or more glasses of milk per day was lower among Asian American and black students than among white and Hispanic students (Table 4). The prevalence among Pacific Islander students was higher than among Asian American students. Among females, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence among Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from other racial/ethnic groups. Among males, the prevalence was lower among Asian American students, higher among black and Hispanic students, and highest among white students. The prevalence among Pacific Islander males was lower than among white males.

Overall, the prevalence of obesity was higher among black and Hispanic students, lower among Pacific Islander and white students, and lowest among Asian American students (Table 4). Among females, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence among Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from that among black and Hispanic students. Among males, the pattern was the same except that the prevalence among Pacific Islander students did not vary significantly from that among Asian American and black students.

Multiple health-risk behaviors

Asian American students demonstrated the lowest prevalence of multiple risk behaviors and the lowest mean number of risk behaviors (Table 5). Of the 12 risk behaviors selected, the prevalence of students reporting more than two of these behaviors was approximately 40% among Asian American students, 60% among white students, 61% among Pacific Islander students, 66% among Hispanic students, and 71% among black students. The mean number of risk behaviors was lower among Asian American students (2.6) than among white (3.6), Pacific Islander (3.8), Hispanic (3.9), and black (4.1) students.

DISCUSSION

Our findings are consistent with a recent literature review of sexual activity and alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use among adolescents that found Asian American young people had the lowest prevalence of risk-taking behaviors among major racial/ethnic groups.10 That study and others have found that Asian American adolescents reported lower rates of sexual activity and illicit drug use than other racial/ethnic groups, and lower rates of alcohol and tobacco use than their non-Hispanic white peers.7,14–17 Studies have also demonstrated that once Asian American young people became sexually active, they exhibited sexual behavior patterns similar to other racial/ethnic groups.14–16,27 We found Asian American and black students had the lowest prevalence of tobacco use. Asian American students had the lowest prevalence of alcohol and marijuana use, as well as the lowest prevalence of ever having sexual intercourse, having sexual intercourse with four or more people, and being currently sexually active. Among currently sexually active students, the prevalence among Asian American young people of having drunk alcohol or used drugs before last sexual intercourse, and having used a condom during last sexual intercourse, was similar to young people of other racial/ethnic groups. The prevalence of sexual behaviors and substance use among Pacific Islander students was similar to that among white and Hispanic students.

Few studies have been published on the prevalence of behaviors that result in intentional or unintentional injury among Asian American and Pacific Islander young people. A national study found Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents as a combined group were less likely to carry a weapon or be in a physical fight and were more likely to wear a seat belt than their white, black, and Hispanic counterparts.15 Our study found a similar pattern among Asian American students; however, the prevalence of weapon-carrying, physical fighting, and seat belt use among Pacific Islander students was similar to black and Hispanic students.

Previous research found the prevalence of suicide attempts among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents as a combined group did not vary significantly from adolescents of other racial/ethnic groups.15 However, where data have been disaggregated, Asian American groups have been found to have substantially lower rates of completed suicide than white people, while rates of completed suicide among Pacific Islander populations are some of the highest in the world.28 Suicide is the leading cause of injury-related death in Hawaii.28 Recent surveys conducted in five U.S. Pacific Island territories (American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Republic of Palau) found prevalence estimates for suicide attempts among adolescents consistently exceeded the U.S. average.12,29 Unfortunately, research on completed and attempted suicide among Pacific Islanders is very limited, despite the fact that suicide among this population group remains a major public health issue.28 In our study, Pacific Islander students had a higher prevalence of having seriously considered attempting suicide (26.2%) and having attempted suicide (18.3%) than did all other racial/ethnic groups, while Asian American students were similar to white and Hispanic students in the prevalence of having seriously considered attempting suicide and were similar to black and Hispanic students in the prevalence of having attempted suicide.

Information on risk behaviors for chronic disease among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents also is limited. Our findings are consistent with a study of adolescents in California that found Asian American young people were less physically active, ate more vegetables, and drank less milk than white adolescents.18 We found Pacific Islander students to be similar to Asian American, black, and Hispanic students in the prevalence of regular participation in vigorous and moderate physical activity; however, Pacific Islander students had the highest consumption of fruit and vegetables of students of all racial/ethnic groups and drank more milk than Asian American students. In a previous study, the prevalence of obesity was lower among Asian American adolescents than among white, black, or Hispanic adolescents.19 Although few data have been published on the prevalence of obesity among Pacific Islander young people, the prevalence of obesity is typically high among Pacific Islander populations.30–32 In our study, the prevalence of obesity among Asian American adolescents was lower than among all other racial/ethnic groups, while the prevalence among Pacific Islander adolescents was similar to that among white adolescents, but lower than that of black and Hispanic adolescents.

Our study was able to calculate national prevalence estimates for a broad range of health-risk behaviors for Asian American and Pacific Islander students separately and to compare these prevalence estimates with those of white, black, and Hispanic students. Although Asian American students had the lowest prevalence estimates for most risk behaviors, a large proportion of students from every racial/ethnic group reported multiple behaviors that place them at risk for poor health outcomes.

Limitations

There were several limitations of our study, which should be acknowledged. First, because we combined data during a six-year period, it is possible that the prevalence of some of these behaviors may have changed over time. Second, we lacked data that would allow us to further examine ethnic subgroup differences among Asian American students and Pacific Islander students. Previous research has observed large variations in health disparities and risk behaviors among different subgroups of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.1,7,29,33,34 Finally, we lacked data on factors such as family and community structure, cultural and ethnic values and attitudes, stage of acculturation, and socioeconomic status that might help to explain the behavioral patterns exhibited by different racial/ethnic groups.14,28,35–39 Without the context provided by information on social, economic, environmental, and cultural factors, we must be cautious in interpreting racial/ethnic differences in the risk behaviors of Asian American and Pacific Islander young people.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study showed that the prevalence of important health-risk behaviors varies by race/ethnicity, and in particular, the risk behavior profiles of Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents vary dramatically. Prevalence estimates for Asian American adolescents were significantly different from those for Pacific Islander adolescents for 16 of the 20 risk behaviors examined. It appears that combining health-risk behavior data for Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents does, in fact, obscure important differences. Whenever feasible, health surveys should oversample Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents, as is often done for black and Hispanic populations, or, alternatively, combine multiple years of data to provide separate prevalence estimates for Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents. Surveys that provide data on Asian American and Pacific Islander subgroups as well as other racial/ethnic and multiracial/multiethnic populations would assist in the development and implementation of targeted, culturally, and ethnically competent public health policies and programs to improve the health and well-being of all adolescents.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Adv Data no 394. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Jan 22, Health characteristics of the Asian adult population: United States, 2004–2006; pp. 1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes JS, Bennett CE. The Asian population: 2000. Census 2000 Brief. Washington: Department of Commerce, Census Bureau (US); 2002. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 3.Census Bureau (US). An older and more diverse nation by midcentury [press release]; 2008. Aug 14, [cited 2010 Aug 9]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html.

- 4.Reeves TJ, Bennett CE. Current Population Reports, P20-540. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2003. May, The Asian and Pacific Islander population in the United States: March 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves TJ, Bennett CE. We the people: Asians in the United States—Census 2000 special reports. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris PM, Jones NA. We the people: Pacific Islanders in the United States—Census 2000 special reports. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki PY, Kameoka VA. Ethnic variations in prevalence of high-risk sexual behaviors among Asian and Pacific Islander adolescents in Hawaii. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1886–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juang LP, Cookston JT. A longitudinal study of family obligation and depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23:396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0015814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fryar CD, Merino MC, Hirsch R, Porter KS. Smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use reported by adolescents aged 12–17 years: United States, 1999–2004. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2009 May 20;15:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2008: volume I, secondary school students (NIH Publication No 09-7402) Bethesda (MD): National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavin L, MacKay AP, Brown K, Harrier S, Ventura SJ, Kann L, et al. Sexual and reproductive health of persons aged 10–24 years—United States, 2002–2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(6):1–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA. 2008;299:2401–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tosh AK, Simmons PS. Sexual activity and other risk-taking behaviors among Asian-American adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunbaum JA, Lowry R, Kann L, Pateman B. Prevalence of health risk behaviors among Asian American/Pacific Islander high school students. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:322–30. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuster MA, Bell RM, Nakajima GA, Kanouse DE. The sexual practices of Asian and Pacific Islander high school students. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:221–31. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace JM, Jr, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM. Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use: racial and ethnic differences among U.S. high school seniors, 1976–2000. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S67–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen ML, Elliot MN, Morales LS, Diamant AL, Hambarsoomian K, Schuster MA. Adolescent participation in preventive health behaviors, physical activity, and nutrition: differences across immigrant generations for Asians and Latinos compared with whites. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:337–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Popkin BM. Ethnic differences in physical activity and inactivity patterns and overweight status. Obes Res. 2002;10:141–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, Ross JG. Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:336–42. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen SA, Greenbaum JA, Whalen L, Eaton D, et al. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53(RR-12):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross S, Kawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55(5):1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross S, Kawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2003. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2004;53(2):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2001. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(SS-4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN®: Version 9.0.1. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cochran SD, Mays VM, Leung L. Sexual practices of heterosexual Asian-American young adults: implications for risk of HIV infection. Arch Sex Behav. 1991;20:381–91. doi: 10.1007/BF01542618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Else IR, Andrade NN, Nahulu LB. Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Stud. 2007;31:479–501. doi: 10.1080/07481180701244595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lippe J, Brener N, Kann L, Kinchen S, Harris WA, McManus T, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—Pacific Island United States territories, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(12):28–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez BL. Dietary studies in the multi-ethnic Hawaiian population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:209–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taira D, Gronley K, Chung R. Patient characteristics, health status, and health related behaviors associated with obesity. Hawaii Med J. 2004;63:150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chai D, Kaluhiokalani N, Little J, Hetzler R, Zhang S, Mikami J, et al. Childhood overweight problem in a selected school district in Hawaii. Am J Hum Biol. 2003;15:164–77. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwong SL, Chen MS, Jr, Snipes KP, Bal DG, Wright WE. Asian subgroups and cancer incidence and mortality rates in California. Cancer. 2005;104(12 Suppl):2975–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le LT, Kiely JL, Schoendorf KC. Birthweight outcomes among Asian American and Pacific Islander subgroups in the United States. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:973–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.5.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn MK, Juon HS, Gittelsohn J. Association of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, acculturation, and environmental factors with risk of overweight among adolescents in California, 2003. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi S, Rankin S, Stewart A, Oka R. Effects of acculturation on smoking behavior in Asian Americans: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305057.96247.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussey JM, Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Iritani BJ, Halpern CT, Bauer DJ. Sexual behavior and drug use among Asian and Latino adolescents: associations with immigrant status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9:85–94. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willgerodt MA, Thompson EA. Ethnic and generational influences on emotional distress and risk behaviors among Chinese and Filipino American adolescents. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:311–24. doi: 10.1002/nur.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unger JB, Reynolds K, Shakib S, Spruljtet-Metz D, Sun P, Johnson CA. Acculturation, physical activity, and fast-food consumption among Asian-American and Hispanic adolescents. J Community Health. 2004;29:467–81. doi: 10.1007/s10900-004-3395-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]