The National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) is a federal advisory committee that provides vaccine and immunization policy recommendations to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The NVAC's diversity of professional and stakeholder perspectives enables the committee to play a role in strengthening the U.S. vaccine and immunization system, as well as inform vaccine policy. This article details the NVAC's contribution, focusing on its recent response to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and reveals opportunities for the NVAC to further shape this public health sector in the future.

A NEW PANDEMIC

Independent expert advice is a critical element of developing government health policy. Never has this been more important than during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, as evidenced by the contributions of the NVAC toward shaping vaccine and immunization policy recommendations to HHS.

On April 26, 2009, the U.S. government declared a public health emergency and the nation's pandemic response plan was activated.1 Development and distribution of a safe and effective H1N1 vaccine became a high priority both in the United States and abroad to ensure community health and slow the spread of disease. Based on both past work and current expertise, the NVAC issued a series of recommendations addressing safety, communications, and financing to HHS.

To address some of the challenges posed by the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza mass vaccination program, the NVAC established the H1N1 Vaccine Safety Subgroup. The Subgroup was charged with reviewing the current federal plans for safety monitoring during the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine campaign and providing feedback to NVAC and ultimately HHS on the program's adequacy, strengths, and weaknesses. The NVAC approved four recommendations to improve safety monitoring in preparation for the 2009 H1N1 vaccination program:2

Develop a clear federal plan to monitor 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine safety;

Enhance active surveillance, linking exposure data (vaccine histories) to outcomes data, to rapidly answer vaccine safety questions that may arise;

Establish a transparent and independent group to review vaccine safety data as they accumulate; and

Develop and test responses to scientific and public concerns about vaccine safety by assembling background rates of disease and organizing drills or practice scenarios.

HHS adopted all of the NVAC's recommendations. First, HHS, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) developed a federal plan to monitor H1N1 vaccine safety.3 The federal plan included enhancements to active surveillance and rapid development of new systems to monitor vaccine safety. Second, enhancements to active surveillance included accelerating the development of systems that were being pilot tested at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services through their Medicare database and at the VA through existing systems to monitor the safety of vaccines for veteran patients, VA employees, and volunteers. New systems included the Post-licensure Rapid Immunization Safety Monitoring network, a system for monitoring the safety of 2009 H1N1 monovalent vaccine in near real time; use of the Indian Health Service Resource and Patient Management Database; and population-based Guillain-Barráe syndrome Active Case Finding through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Emerging Infections Program.3 These and other enhanced active surveillance activities satisfied the second NVAC H1N1 vaccine safety recommendation.

To implement the third safety monitoring recommendation, the NVAC created the H1N1 Vaccine Safety Risk Assessment Working Group (VSRAWG). The VSRAWG provides rapid, ongoing, and independent assessments of vaccine safety data as they accumulate and reports them to the NVAC, HHS, and the public.

Two strategies fulfilled the fourth NVAC recommendation. The federal government and other countries assembled background rates for a wide variety of outcomes using multiple systems and data sources published prior to initiation of the 2009 H1N1 vaccine program; this data collection enabled a truer contextual understanding of disease rates that would occur by chance alone following vaccination.4 Pre-pandemic tabletop exercises in 2007–2008 by senior HHS officials, communications teams, and local health departments with media markets across the country served as a foundation for two 2009 sessions in New York and Minnesota to inform broadcast and print media on H1N1, with safety monitoring as a key issue.5

The NVAC also encouraged HHS to use Internet-based new and social multimedia to disseminate accurate health information and dispel misinformation, especially through the use of the HHS influenza website, www.Flu.gov. These strategies complemented the department's traditional seasonal influenza campaign, which focused on providing rapid communications through weekly media briefings and targeted public service announcements, webcasts, and webinars for special populations (e.g. pregnant women and health-care workers), who were prioritized to receive the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine. This blend of media outreach and a comprehensive messaging strategy fulfilled the NVAC's recommendation to address public concerns.6

The NVAC's third area of focus in response to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic related to improving access to the vaccine by reducing financial barriers. The NVAC issued financing recommendations covering four main areas:7

First-dollar coverage for administration of the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine,

Reimbursement and reimbursement rates for vaccine administration,

Billing practices of community vaccinators, and

Federal funding for state and local mass immunization campaigns.

Stakeholders heeded these recommendations, with some health insurance plans providing first-dollar coverage and eliminating cost sharing for their patients to receive the 2009 H1N1 vaccine.8,9 The federal government provided funds to states to help implement the vaccination program, including funds to help cover the cost of vaccine administration in clinics organized by the public sector. The government also issued federal guidance documents related to H1N1 financing and vaccine administration billing.

THE ROLE OF THE NVAC

The NVAC's thoughtful recommendations on H1N1 vaccine policy were due to the committee's longstanding commitment to identifying key issues and providing timely recommendations, as well as to the nature of the committee itself. Since its inception in 1987, the NVAC has been offering advice and recommendations to HHS on a broad range of vaccine-related issues. Specifically, the NVAC was chartered with four main responsibilities: (1) study and recommend ways to encourage the availability of an adequate supply of safe and effective vaccination products in the U.S.; (2) recommend research priorities and other measures that should be taken to enhance the safety and efficacy of vaccines; (3) advise the Assistant Secretary for Health (ASH) on the implementation of the National Vaccine Program's (NVP's) responsibilities and the National Vaccine Plan, a coordinated, strategic framework established to achieve the vision of the NVP; and (4) identify the most important areas of government and nongovernment cooperation that should be considered in implementing the NVP's responsibilities and the National Vaccine Plan.10

The NVAC's work has contributed to a better understanding of challenges facing the complex and dynamic system responsible for vaccine development, delivery, financing, and evaluation. For example, in 1991, the NVAC issued a seminal white paper to address a three-year resurgence of measles, “The Measles Epidemic: The Problems, Barriers, and Recommendations,” which outlined problems with the immunization system, barriers to maintaining high coverage levels, and a blueprint for improvement.11 The Measles White Paper would inform the Childhood Immunization Initiative Act of 1993, ultimately leading to increased immunization rates among preschool-aged children, a reduction in vaccine-preventable diseases, and the creation of the Vaccines for Children program. Other components of the current immunization system that derived from the Measles White Paper included support for health services research to identify determinants for low immunization coverage and interventions to improve uptake and standards for immunization practices, such as the creation of the National Immunization Survey, which has annually measured childhood immunization coverage since 1994.12

In 1997, the NVAC issued a paper on the vaccine development process, which described the “delicate fabric” of the loose network of cooperative and collaborative partnerships that are required to fully realize the promise of new science and technology in developing innovative, novel vaccines.13 The committee has continued to work in this area. In 1999, it issued a case history analysis of selected vaccines, which highlighted key lessons in vaccine research and development. These lessons have helped shape future development pathways.14 Later, in 2003 and 2005, the NVAC conducted several extensive workshops, bringing together members of various constituencies involved in vaccine supply (e.g., manufacturers, regulatory authorities, purchasers, distributors, consumers, state and local public health authorities, scientists, advocacy groups, and legislators). These workshops identified five general issues that needed to be addressed to strengthen the supply of routinely administered vaccines. These issues related to (1) providing incentives to maintain and encourage manufacturers to the market; (2) streamlining regulatory authority; (3) strengthening liability protections for consumers, manufacturers, and providers; (4) implementing more comprehensive stockpiles; and (5) developing an educational program that would provide information to parents and vaccine recipients about the usage and value of licensed vaccines.15

More recently, from 2006 through 2008, the NVAC examined how the lack of comprehensive vaccine financing threatens the ability of the current system to deliver immunizations to all of the recommended populations, even those with health insurance.16 To address this issue, the committee formed a Vaccine Financing Working Group comprising a diverse set of stakeholders, including health plans, providers, and manufacturers. Through extensive engagement with partners across industry, legislators, health insurance representatives, and consumers, the NVAC issued 24 recommendations to reduce or eliminate financial barriers to childhood and adolescent immunizations.16 These recommendations were the platform for 2009 recommendations on financing the H1N1 vaccine, allowing for higher coverage rates and reduced disparities.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE NVAC

The NVAC is structured to assess vaccine policy and make recommendations through working groups. These working groups gather information, develop policy options, and draft recommendations for full committee deliberation. The composition of working groups may include members of the committee itself as well as other individuals with specific expertise. These outside experts may represent themselves or academia; manufacturers; the health insurance industry; health-care providers; federal, state, and local health departments; consumers; or other federal government agencies. As a Federal Advisory Committee Act sanctioned committee, its deliberations and votes are open to the public. Recommendations approved by a majority vote are forwarded to the ASH for review and further consideration by HHS.10

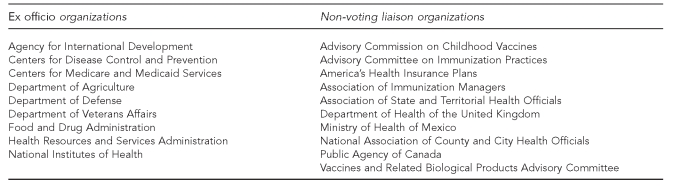

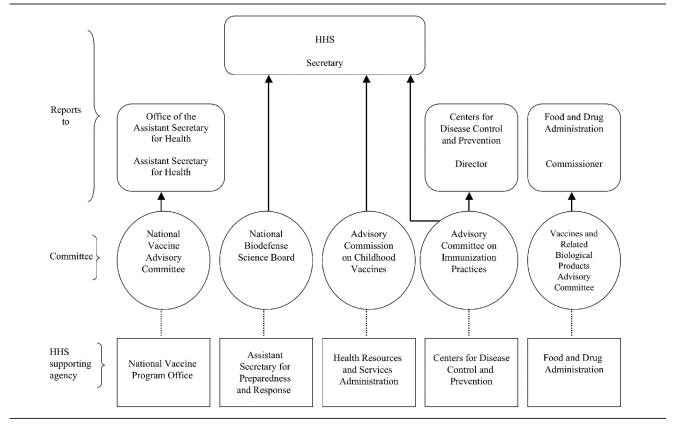

NVAC membership reflects a broad representation of immunization stakeholders. The 17 voting committee members include a chair; 14 additional public members representing a wide range of perspectives, including physicians, consumer organizations with an interest in immunizations, state and local health agencies, or public health organizations; and two members who are engaged in vaccine research or the manufacturing of vaccines.10 Federal agencies involved in the vaccine and immunization system serve as ex officio members, and liaison members represent key stakeholders, including the health insurance industry and other federal advisory committees (Figure 1). Additionally, the Executive Secretary of the NVAC has a role as an ex officio member on other HHS advisory committees, such as the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Vaccines Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

National Vaccine Advisory Committee non-voting ex officio and non-voting liaison members

Figure 2.

Reporting structure of vaccine and immunization-related HHS federal advisory committees

HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

As the NVAC is a subset of the broad vaccine and immunization community, stakeholder input is invaluable to informing vaccine policy. The NVAC's emphasis on diverse membership, as well as its consistent history of public and stakeholder engagement, provides a forum for these stakeholders to provide their perspectives and considerably strengthens the NVAC as an advisory group.17,18 This consultative process of gathering input from a wide range of participants serves two core functions. First, stakeholders provide useful information to decision makers on policy issues from a range of perspectives that reflect the broader values and perspectives of society. Second, stakeholder engagement increases the likelihood that these same key stakeholders may contribute to implementing NVAC recommendations, where appropriate.19

CONCLUSION

From past work outlining problems and barriers to increasing and sustaining coverage levels and H1N1 planning to present-day work on key issues such as adult immunization and the implications of health-care reform, the NVAC demonstrates the capacity and role of an advisory committee to provide recommendations and guidance on critical public health issues. The NVAC provides broad perspectives from a variety of stakeholders who are not represented in other HHS advisory committees, such as state and local public health and the vaccine industry. Through this body, contemporary issues relevant to vaccines and immunization have been examined and debated.

Elusive vaccine targets for development, public concerns about vaccine safety, barriers to adult immunization, a vulnerable vaccine supply, vaccine financing issues, and regulatory issues are some of the many complex issues facing the U.S. vaccine and immunization system going forward. The NVAC is well-positioned to provide strategic recommendations with stakeholder input to address gaps in and improve the overall system.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank National Vaccine Advisory Committee members past and present, key stakeholders, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) staff for their thoughtful review of this article.

Footnotes

The research by Jovanni Spinner was performed under an appointment to HHS, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education under Contract # DE-AC05-06OR23100 between the U.S. Department of Energy and Oak Ridge Associated Universities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (US). What is the history of the 2009 H1N1 swine flu? When did the swine flu start? [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://answers.flu.gov/questions/4300.

- 2.National Vaccine Advisory Committee. 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine safety monitoring recommendation. 2009. Aug, [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/index.html.

- 3.HHS (US), Federal Immunization Safety Task Force. Federal plans to monitor immunization safety for the pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination program. 2009. [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.flu.gov/professional/federal/fed-plan-to-mon-h1n1-imm-safety.pdf.

- 4.Black S, Eskola J, Siegrist CA, Halsey N, MacDonald N, Law B, et al. Importance of background rates of disease in assessment of vaccine safety during mass immunization with pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccines. Lancet. 2009;274:2115–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61877-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HHS (US) National Vaccine Advisory Committee Teleconference Meeting: 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak and response. 2009. Aug 24, [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/minutes200908.html.

- 6.National Vaccine Advisory Committee. 2009 H1N1 influenza communications recommendations. 2009. Aug, [Cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/index.html.

- 7.National Vaccine Advisory Committee. 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination program financing recommendations. 2009. Jul, [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/index.html.

- 8.UnitedHealthcare. UnitedHealth Group will cover administration of H1N1 vaccine [press release] 2009 Aug 20. [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.uhc.com/news_room/2009_news_release_archive/unitedhealth_group_will_cover_administration_of_h1n1_vaccine.htm.

- 9.Medical News Today. WellPoint announces decision to cover H1N1 vaccine administration [press release] 2009 Jul 31. [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/159404.php.

- 10.HHS (US). Charter: National Vaccine Advisory Committee. 1987. Jul 30, [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://archive.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/history/nvac_firstchapter_1987_adj.pdf.

- 11.National Vaccine Advisory Committee. The measles epidemic: the problems, barriers, and recommendations. JAMA. 1991;266:1547–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). National Immunization Survey. [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nis/Default.htm.

- 13.Marceuse EK. United States vaccine research: a delicate fabric of public and private collaboration. Pediatrics. 1998;102(4 Pt 1):1002–3. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.4.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peter G, des Vignes-Kendrick M, Eickhoff TC, Fine A, Galvin V, Levine MM, et al. Lessons learned from a review of the development of selected vaccines. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4 Pt 1):942–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoli JM, Peter G, Arvin AM, Davis JP, Decker MD, Fast P, et al. Strengthening the supply of routinely recommended vaccines in the United States: recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. JAMA. 2003;290:3122–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.23.3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Financing vaccination of children and adolescents: National Vaccine Advisory Committee recommendations. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 5):S558–62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HHS (US). The National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) public engagement activities. [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/vacc_plan/engagement.htm.

- 18.The Keystone Center. The public engagement project on the H1N1 pandemic influenza vaccination program: final report. Keystone (CO): The Keystone Center; 2009. Sep, [cited 2010 Aug 17]. Also available from: URL: http://keystone.org/files/file/about/publications/Final-H1N1-Report-Sept-30-2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagle U. The policy science of democracy: the issues of methodology and citizen participation. Policy Sci. 2000;33:207–23. [Google Scholar]