SYNOPSIS

Objectives

We investigated the incidence of hospital utilization for injuries and compared poisoning with other forms of injury. Previous studies have suggested poison control centers reduce health-care costs by decreasing hospital utilization.

Methods

We conducted a one-year retrospective study involving patients treated for injuries at acute-care hospitals in Kentucky in 2008. We also compared inpatient discharges with discharges directly from the emergency department (ED) to determine hospitalization rates. The primary data sources were the Kentucky Hospital Billing database and the Kentucky Regional Poison Control Center (KRPCC) database.

Results

In 2008, there were 377,642 hospital encounters for injuries in Kentucky. The most common mechanisms of injury were falls, struck by/against, motor vehicle traffic crashes, and overexertion. Three causes of injury were greater than one standard deviation above the mean in percentage of inpatient admissions: poisoning (41.3%), firearms (38.4%), and drowning (22.4%). During this same year, KRPCC reported 46,258 poisonings, with 76.5% of patients managed outside of a health-care facility, 11.4% of patients treated and released from the ED, 7.1% of patients admitted to inpatient care, 2.3% of patients admitted to psychiatric care, and 2.7% lost to follow-up.

Conclusions

Conclusions. Three causes of injury had the greatest percentage of patients admitted for inpatient medical care—poisoning, firearms, and drowning—suggesting a high level of severity in these injuries presenting to the ED. We believe availability and use of a poison control center reduced hospital utilization for poisoning primarily by managing a large number of low-severity patients outside of the hospital system.

Overutilization of emergency departments (EDs) for non-emergent care remains a problem.1–4 For a number of patients, including those with injuries, use of the ED may seem justified from the patient's perspective because the patient believes his or her symptoms are serious.5 However, utilization of EDs can be impacted by a number of factors, including cost (e.g., patient deductible), level of severity, use of a primary care physician, and availability of a poison control center (PCC).1,3,4,6,7

PCCs in the U.S. manage more than 75% of reported poisonings outside of a health-care facility.8 This management has resulted in significant health-care cost savings—estimated at >$900 million per year—by reducing ED utilization.9 In 2005, Medicare, Medicaid, and the State Children's Health Insurance Program were the primary payers in 47% of nonfatal poisoning hospital admissions, so much of these savings directly benefited federal and state governments.10,11 The reduction of ED utilization occurred primarily in patients who did not need emergent medical care but would likely have used the ED had there not been a PCC to contact.12

An example of a minor poisoning case that could be managed at home would be a normally healthy 2-year-old child who ingests 10 over-the-counter, 100-milligram (mg) ibuprofen tablets. While this would likely be frightening for the parent and cause mild gastritis and stomach pain for the child, it would not require ED care or direct, hands-on medical intervention. However, if this same child ingested 10 over-the-counter, 25-mg diphenhydramine tablets, an ED visit would be warranted.

A number of studies have examined the cost savings by PCCs from reduced ED utilization.7,12–19 The primary concept of this reduction is that 24-hour, free public access to highly trained health-care professionals allows appropriate triage and frequent redirection from what would have been, for many of these patients, a self-referral to the hospital ED.

To investigate this idea further, we evaluated hospital encounters for all injuries, including poisoning, for one year to compare the number of inpatient discharges with the number of patients discharged directly from the ED for these injuries. We investigated the incidence of hospital utilization for injuries and compared poisoning with other forms of injury. For the purpose of this study, we considered the ratio of inpatient discharges to total hospital encounters to be the hospital admission rate. Additionally, we reviewed all poisonings reported to the Kentucky Regional Poison Control Center (KRPCC), which served the same population during the same time period, as a second source of information on the number of poisonings occurring in the population.

Methods

Data sources

We conducted a one-year retrospective study involving all patients treated for an injury or poisoning at any licensed, acute-care hospital in the state of Kentucky in 2008. The primary data sources were the Kentucky Hospital Billing database and the KRPCC database.

KRPCC database.

We obtained PCC data for 2008 from the KRPCC. KRPCC created an individual electronic medical record on each patient and stored these in a searchable database. As part of each medical record, a number of data were recorded, including patient demographics (age, gender, and geographic location), specific substances involved in the case, resultant clinical effects, therapies employed, and medical outcome. The “patient management site” variable was coded as: (1) patient managed on-site (outside of a health-care facility), (2) patient already in (en route to) a health-care facility when the PCC was contacted, (3) patient referred by the PCC to a health-care facility, (4) other, or (5) unknown. Patients managed in a health-care facility were coded as: (1) treated/evaluated and released, (2) admitted to critical care, (3) admitted to non-critical care, (4) admitted to a psychiatric facility, or (5) lost to follow-up. We excluded from the study patients managed by KRPCC outside of Kentucky (e.g., in Indiana). KRPCC receives calls from all acute-care hospitals within Kentucky, as well as from the general public in all 120 state counties.

Kentucky Hospital Billing database.

Since 1996, Kentucky Administrative Regulations (900 KAR 7:030, “Data reporting by health-care providers”) have mandated reporting of all inpatient hospitalizations by licensed, acute-care hospitals and all encounters involving outpatient surgical or mammography procedures or services by the same hospitals, as well as ambulatory surgery centers. In addition to these mandated submissions, effective January 1, 2008, the regulation was updated to include reporting of all ED and observation care visits. Observation care typically involves a stay of less than 24 hours, with no admission.

Among the data elements facilities are required to report are patient demographics (age, gender, and race/ethnicity), admission and discharge dates, diagnostic and procedure codes, charges billed, patient disposition, and external cause of injury codes (hereafter, E-codes).

Analysis

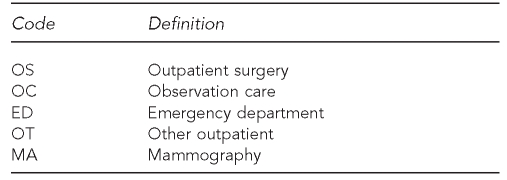

In Kentucky, hospital outpatient billing records are classified into one of five service types, based on the reported Current Procedural Terminology and revenue codes from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The service types and their definitions are provided in Figure 1. If a patient receives outpatient services (e.g., in an ED) and is admitted, the inpatient billing record will include those services; there will not be a separate outpatient billing record.

Figure 1.

Codes and related service types for Kentucky hospital outpatient billing records, 2008

For this study, we counted as hospital encounters all inpatient records and any outpatient record classified as ED or observation care. We excluded records classified as other outpatient and outpatient surgery because our primary interest was ED utilization. We also excluded mammography records.

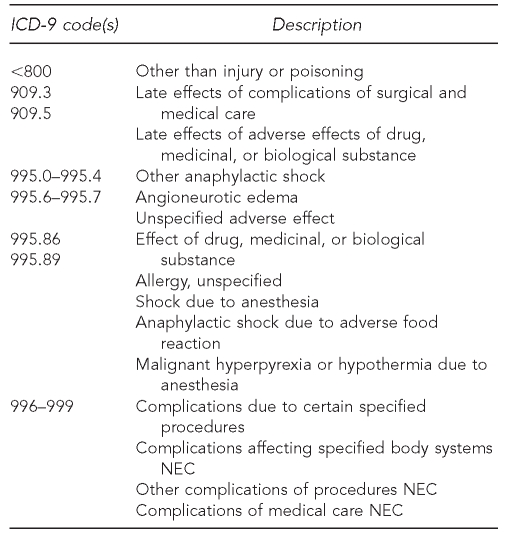

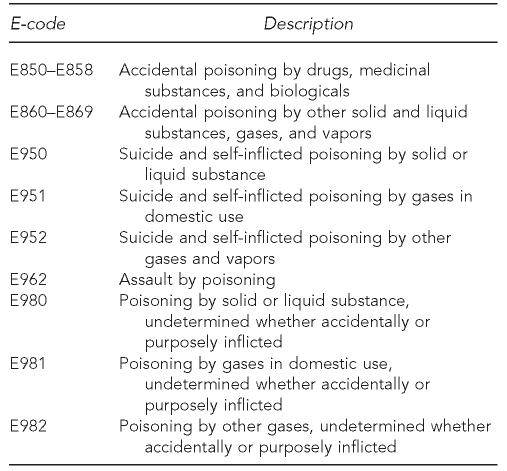

To identify injury and poisoning cases in the hospital database and classify them by the mechanism of injury, we followed the State and Territorial Injury Prevention Directors Association's (STIPDA) Consensus Recommendations for Using Hospital Discharge Data for Injury Surveillance.20 Based on STIPDA guidelines, observations with a principal diagnosis listed in Figure 2 were excluded from this study. We then classified each injury or poisoning observation into one of 19 mechanism categories based on the first listed E-code. Each category includes injuries or poisonings of all manner, whether unintentional, self-inflicted, assaultive, or undetermined. The poisoning mechanisms are provided in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Principal diagnoses excluded from study based on STIPDA case definition for injury and poisoning on hospital discharge databases

STIPDA = State and Territorial Injury Prevention Directors Association

ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

NEC = not elsewhere classified

Figure 3.

Poisoning mechanism categories into which acute-care hospital encounters for injury and poisoning were classified, Kentucky, 2008

E-code = external cause of injury code

RESULTS

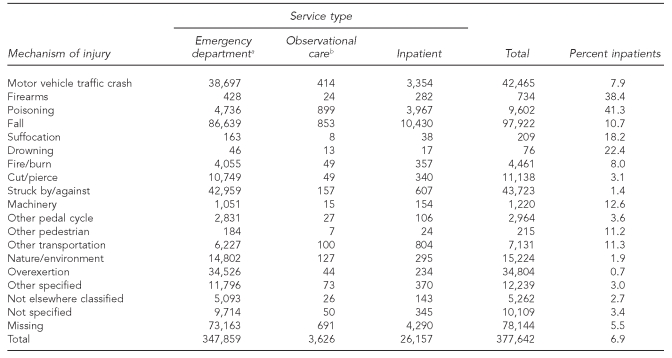

In 2008, there were 377,642 hospital encounters for injuries in Kentucky. Of these patients, 347,859 (92.1%) were treated and released from the ED; 3,626 (1.0%) received an observational stay, and 26,157 (6.9%) were admitted as inpatients (Table, Figure 4). The most common mechanisms of injury that had any kind of hospital encounter (e.g., ED, inpatient, or observational stay) were falls, struck by/against, motor vehicle traffic crashes, and overexertion. The most common mechanisms of injury that resulted in an inpatient hospitalization were falls, poisoning, and motor vehicle traffic crashes.

Table.

Acute-care hospital encounters for injury and poisoning, by mechanism of injury and service type, Kentucky, 2008

aTreated and released

bHeld as outpatient for observation <23 hours and released

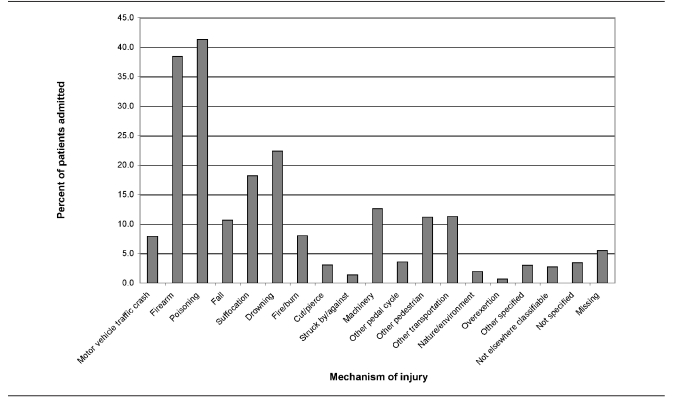

Figure 4.

Percentage of patients admitted for inpatient care for injury or poisoning, by mechanism of injury, Kentucky, 2008

When we evaluated the cause of the hospital encounter by specific type of injury, the mean percentage of all patients admitted to inpatient care was 10.7% (standard deviation [SD] = 11.5). Three causes of injury were greater than one SD above the mean in percentage of inpatient admissions: poisoning (41.3%), firearms (38.4%), and drowning (22.4%).

When evaluating the cause of the hospital encounter for the combined groups of patients admitted for inpatient care and patients with an observational stay, the mean was 13.4% (SD=14.7) of patients. Three causes of injury were greater than one SD from the mean: poisoning (50.7%), firearms (41.7%), and drowning (39.5%).

During this same one-year period, KRPCC reported 46,258 poisonings in Kentucky. Patients were either managed outside of a health-care facility (76.5%, n=35,396), treated and released from the ED (11.4%, n=5,268), admitted to inpatient critical care (5.7%, n=2,624), admitted to inpatient non-critical care (1.4%, n=648), admitted to psychiatric care (2.3%, n=1,050), or lost to follow-up (2.7%, n=1,272).

DISCUSSION

Severity of diagnosis or injury has a significant effect on the ratio of ED patients who are hospitalized.1,21 In our study, when evaluating patients requiring hospital admission, three causes of injury for the hospital encounter were greater than one SD above the mean: firearms, poisoning, and drowning. One other cause showed hospitalization rates that were greater than the mean but had less than one SD: suffocation.

The high ratio of hospitalization for firearms is likely due to the severity of the injury.21,22 This is also probably the case with suffocation and drowning. Caution should be considered with the rate of suffocation and drowning because the actual numbers for these two causes are very low; therefore, a shift of just a few cases would have a significant impact on the hospitalization ratio (Table). However, the highest hospitalization ratio in our study was for poisoning, which suggests that a large proportion of poisoned patients who do arrive at the ED have a high severity of injury. Similar high hospitalization rates for poisoning have been reported previously from hospital data in Nebraska and Missouri.21 In contrast to this ratio of high severity and/or hospitalization, PCCs in the U.S. report that the large majority of poisonings are of lower severity, with more than 75% of patients managed outside of a health-care facility and only 6% admitted for inpatient medical care.8 These finding are similar to our findings, where only 7% of poisonings reported to the KRPCC resulted in an admission for inpatient medical care. This finding suggests that a large number of low-severity poisonings are not presenting to the hospital, which is consistent with previous studies showing that PCCs reduce ED use by managing low-severity patients outside of a health-care facility.7,12–19

Poisoning is the only injury with a preestablished, 24-hour, free public service for triage and medical advice. When we evaluated poisonings reported to KRPCC during the one-year study period, we found the large majority of poisonings were of lower severity and were managed outside of a health-care facility. We believe our data support the hypothesis that PCCs have a significant impact on reduction of unnecessary ED utilization, which is consistent with previous studies on this subject. Our study located >35,000 poisonings managed outside of the hospital setting by KRPCC. Assuming half of these low-severity poisoning patients had self-referred to the ED if they did not have access to a PCC, the ED census for this cause of injury would have increased by more than 300%, with an increase in hospital charges of more than $25 million in 2008.12,16 This figure is based on mean hospital charges of $1,433 for the 4,736 patients treated in Kentucky EDs for poisoning in our sample. We believe this study provides an interesting way of evaluating a public health program's impact on health-care utilization.

The implications of this study are that loss of PCC services would likely cause a significant increase in ED usage for non-emergent care patients who could be managed in a lower-cost setting. While the expansion of this kind of service to other injuries is probably limited, a different model of telephone case management has been used by pediatric nurse triage lines with documented success.23

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to this study. The criteria we used for selecting injury and poisoning patients were based on the principal diagnosis only. Patients having a secondary injury or poisoning diagnosis with a primary diagnosis other than injury were excluded from this study even if an E-code was present. An expanded definition was recently proposed for use with ED data, which would include injuries and poisonings with a valid E-code regardless of the principal diagnosis.24 It has been shown that this expanded definition is not appropriate for use with inpatient data.25 This incompatibility prevented our full use of the expanded definition when comparing the inpatient and ED datasets.

We used E-codes to classify observations by mechanism; however, for 22% of the identified injury and poisoning cases, no E-code was reported. We investigated these cases, and it turns out that an E-code was reported for nearly all (95%) of the patients with a principal diagnosis of poisoning. Of the cases that were missing E-codes, 96% of the patients had a principal diagnosis of trauma (e.g., fracture or open wound). Additionally, the rate of inpatient hospitalization for this group was 6%, which was well below the mean. Therefore, these cases were unlikely to significantly affect our findings.

We did not attempt to match patients reported by the hospital database with a diagnosis of poisoning to patients reported by KRPCC. However, the number of patients reported by the hospital database and KRPCC were consistent and likely represented the same patient population. Previous work matching and comparing these two groups suggests the majority of these patients were, in fact, the same patients.26 KRPCC is routinely contacted for consultation by the EDs of all acute-care hospitals within the state.

CONCLUSION

In summary, three causes of injury had the greatest percentage of patients admitted for inpatient medical care—poisoning, firearms, and drowning—suggesting a high level of severity in these injuries presenting to the ED. We believe availability and use of a PCC helped reduce hospital utilization for poisoning primarily by managing a large number of low-severity patients outside of the hospital system.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wharman JF, Landon BE, Galbraith AA, Kleinman KP, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Emergency department use and subsequent hospitalizations among members of a high-deductible health plan. JAMA. 2007;297:1093–102. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker LC, Baker LS. Excess cost of emergency department visits for nonurgent care. Health Aff (Millwood) 1994;13:162–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.13.5.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddy RI, Schmaler ME, Epting RJ. Nonemergency emergency room use in patients with and without primary care physicians. J Fam Pract. 1987;24:389–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grumbach K, Keane D, Bindman A. Primary care and public emergency department overcrowding. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:372–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powers MJ, Reichelt PA, Jalowiec A. Use of the emergency department by patients with nonurgent conditions. J Emerg Nurs. 1983;9:145–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu J, Price M, Brand R, Ray GT, Fireman B, Newhouse JP, et al. Cost-sharing for emergency care and unfavorable clinical events: findings from the safety and financial ramifications of ED copayments study. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1801–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Jones P, Litovitz T, Coben J, Steiner C, et al. The impact of poison control centers on poisoning-related visits to EDs—United States, 2003. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Green JL, Rumack BH, Heard SE American Association of Poison Control Centers. 2007 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 25th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46:927–1057. doi: 10.1080/15563650802559632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiller HA, Griffith JR. The value and evolving role of the U.S. Poison Control Center System. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:359–63. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health and Human Services; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Healthcare cost and utilization project: 2005 national inpatient sample. Rockville (MD): AHRQ; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman ED, Jr, Klees BS, Curtis CA. Brief summaries of Medicare and Medicaid: Title XVIII and Title XIX of the Social Security Act. Baltimore: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2006. [cited 2009 Nov 19]. Also available from: URL: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicareProgramRatesStats/downloads/MedicareMedicaidSummaries2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.LoVecchio F, Curry S, Waszolek K, Klemens J, Hovseth K, Glogan D. Poison control centers decrease emergency healthcare utilization costs. J Med Toxicol. 2008;4:221–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03161204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller TR, Lestina DC. Costs of poisoning in the United States and savings from poison control centers: a benefit-cost analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:235–45. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips KA, Homan RK, Hiatt PH, Luft HS, Kearney TE, Heard SE, et al. The costs and outcomes of restricting public access to poison control centers: results from a natural experiment. Med Care. 1998;36:271–80. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baeza SH, III, Haynes JF, Jr, Loflin JF, Saenz E, Jr, Watts SH, Artelejo L., III Patient outcomes in a poison center/EMS collaborative project. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45:622–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.King WD, Palmisano PA. Poison control centers: can their value be measured? South Med J. 1991;84:722–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blizzard JC, Michels JE, Richardson WH, Reeder CE, Schulz RM, Holstege CP. Cost-benefit analysis of a regional poison center. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46:450–6. doi: 10.1080/15563650701616145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Jones P, Litovitz T, Coben J, Steiner C, et al. The potential impact of poison control centers on rural hospitalization rates for poisoning. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2094–100. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearney TE, Olson KR, Bero LA, Heard SE, Blanc PD. Health care cost effects of public use of a regional poison control center. West J Med. 1995;162:499–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.State and Territorial Injury Prevention Directors Association, Injury Surveillance Workgroup. Consensus recommendations for using hospital discharge data for injury surveillance. Marietta (GA): STIPDA; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadman MC, Muelleman RL, Coto JA, Kellermann AL. The pyramid of injury: using ecodes to accurately describe the burden of injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:468–78. doi: 10.1067/s0196-0644(03)00489-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coben JH, Steiner CA. Hospitalization for firearm-related injuries in the United States, 1997. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melzer SM. Pediatric after-hours telephone triage and advice: who benefits and who pays? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:617–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.State and Territorial Injury Prevention Directors Association, Injury Surveillance Workgroup 5. Consensus recommendations for injury surveillance in state health departments. Atlanta: STIPDA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.State and Territorial Injury Prevention Directors Association, Injury Surveillance Workgroup 6. Assessing an expanded definition for injuries in hospital discharge data systems. Atlanta: STIPDA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunn TL, Slvova S, Spiller HA, Colvin J, Bathke A, Nicholson VJ. The effect of poison control center consultation on accidental poisoning inpatient hospitalizations with preexisting medical conditions. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71:283–8. doi: 10.1080/15287390701738459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]