Abstract

Introduction:

More than 11 million cancer survivors are at risk for new cancers, yet many are receiving inadequate guidance to reduce their risk. This study describes smoking trends among a group of cancer survivors (CaSurvivors) compared with a no cancer (NoCancer) control group.

Methods:

The Health Information National Trends Survey 2003, 2005, and 2007 cross-sectional surveys were used in this secondary data analysis. Descriptive statistics were produced, and logistic regressions of current smokers were performed on weighted samples using SUDAAN. The sample included 2,060 CaSurvivors; the average age was 63 years; and the majority of respondents were female (67%), White (80.6%), married, or partnered (52.5%), with at least some college education (57%). The mean time since diagnosis was 12 years; 28.7% reported fair or poor health status.

Results:

The overall smoking rate was 18.7% for CaSurvivors and 21.7% for the NoCancer group. Education (less than college), age (younger), marital status (widowed or divorced), and health care access (none or partial) were significant personal variables associated with a greater likelihood of being a current smoker. Controlling for these variables, there were no differences between the CaSurvivors and NoCancer groups over time. Women with cervical cancer were still more likely to be smokers (48.9%) than other CaSurvivors (p < .001).

Conclusions:

CaSurvivors’ current smoking trends were similar to the control group. While most variation was explained by demographic variables, women with cervical cancer, a smoking-related cancer, had the highest prevalence of smoking. Smoking cessation interventions should be targeted to this high-risk group.

Introduction

Tobacco use is one of the most preventable, yet widespread, causes of cancer and is responsible for 30% of all cancer deaths (American Cancer Society, 2009; Veneis et al., 2004). Smoking is associated with increased risk of at least 15 types of cancer (e.g., lung, bladder, head and neck, esophagus, pancreas, uterine cervix, kidney, and stomach cancers and acute myeloid leukemia) as well as cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases. Since the 1964 Surgeon General's report, smoking rates for U.S. adults have dropped from 42% in 1965 to 19.8% in 2008 (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [BRFSS], 2009; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004).

The number of cancer survivors continues to increase and now represent almost 4% of the U.S. population (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2010). Survivors are at increased risk for developing other cancers, and many of those new cancers are related to tobacco use (Curtis et al., 2006). In addition, continued smoking among survivors is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Klosky et al., 2007). Smoking rates in survivors were reported in two different studies using the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to explore health behaviors in cancer survivors. Bellizzi, Rowland, Jeffery, and McNeel (2005) combined NHIS respondents from four surveys conducted between 1998 and 2001 (n = 7,384 cancer survivors). They found that smoking rates varied by age and primary cancer, with younger (<40 years of age) people and gynecological, lung, larynx, and pharynx cancers having higher rates than other cancer survivors or controls. Coups and Ostroff (2005) used the 2000 NHIS (n = 1,646) and also found that smoking rates varied by age (<40 years) and primary cancer, with cervical and uterine cancers associated with higher rates. In a cross-sectional survey of cancer survivors (n = 9,105), smoking rates ranged from 7.4% to 11.9%, with bladder cancer having the highest rate (Blanchard, Courneya, & Stein, 2008). Using the NCI's Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 2003 data, Mayer et al. (2007) found that 22.5% of survivors were current smokers, with differences found by tumor type (breast and prostate cancer the lowest and cervical cancer the highest). Despite these findings, few cancer survivors are counseled about smoking cessation by their providers (Sabatino et al., 2007).

While smoking trends in the general U.S. population continue on a downward trend, there are higher smoking rates in men, younger people (<44 years), and White people (CDC, 2009). As suggested in previous studies, other variables may influence smoking rates among cancer survivors. Further exploration is needed to confirm these findings and to gain a better understanding of these variations. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the role that type of cancer has on current smoking rates among survivors from 2003 to 2007. Results will be useful in developing targeted smoking cessation interventions for higher risk cancer survivors.

Methods

Measures

The HINTS, developed by the NCI, is a biannual national probability population survey to examine cancer communication trends over time (Nelson et al., 2004). Survey questions addressed health communication, health services, behaviors and risk factors, cancer, health status, and demographics. The random digit–dial telephone surveys were collected in English and Spanish (NCI, 2003, 2005, 2007). National probability sampling was done based on the most current population survey with oversampling of Black and Hispanic people in 2003 and 2007. Based on the American Association for Public Opinion Research's (AAPOR) best practices for reporting, the overall response rates were 33% in 2003, 24.1% in 2005, and 24.2% in 2007 (AAPOR, 2010; NCI, 2010).

After obtaining institutional review board exemption status and submitting an application to the NCI, datasets were obtained from all three surveys along with relevant reports, codebooks, and replicate weights. The relevant questions regarding smoking were Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life (yes/no)? and Do you now smoke cigarettes (every day, some days, not at all)? Based on answers to these two questions, respondents were categorized into never, former, or current smokers.

Participants

A total of 19,629 respondents to the three HINTS surveys (2003, 2005, and 2007) included 2,637 (13.4%) with a self-reported diagnosis of cancer. Of these, 577 respondents were excluded due to reporting only a nonmelanoma skin cancer (n = 551), not reporting the type of cancer (n = 18), or giving an inconsistent response (e.g., a female with prostrate cancer, n = 8). Thus, 2,060 respondents were included as having an identifiable cancer other than a nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Analytic Methods

Analyses were performed using software designed for the analysis of complex samples (SUDAAN rel. 10.0; Research Triangle Institute, Durham, NC) using sample weights that were designed to provide unbiased estimations of population totals while accounting for the sample design and nonresponse. These weights, provided by the NCI, were calibrated for age, gender, education, marital status, race and ethnicity, and census region based on the most current U.S. Census data. SEs were calculated with the jackknife technique, using replicate samples provided by the NCI.

Smoking status of CaSurvivors and NoCancer respondents was compared by chi-square. Among cancer survivors, the effects of factors known to affect the likelihood of being a current smoker were assessed by logistic regression. Those factors were age, education, race or ethnicity, marital status, health access, and gender. Since three surveys were pooled, the year of the survey was included to improve the estimates. For survivors of each type of cancer, the likelihood of being a current smoker was compared with that for the survivors of all other types of cancer adjusted by logistic regression for the same variables noted earlier, except that gender was excluded from analyses where the cancer was gender specific (breast, cervical, uterus, ovarian, and prostate). Estimates were obtained using the same procedures described above. The result for a cancer type was reported as significant if the probability of the likelihood ratio test was less than .05 and the estimate of the adjusted odds ratio was greater than 2.00 or less than .50. That is, we have combined the conventional criterion for a test with a standard that aims to assure practical significance as well. We adopted these dual criteria because methods for controlling Type I error rates in families of tests are not well developed for the type of comparison in this analysis in which the tests are between each single group versus the remainder of the sample rather than simultaneously between all pairs of mutually exclusive groups and in which the response variable is binary rather than continuous. Since this is an exploratory study and the number of survivors for some cancer types was low, we wished to preserve findings that could have practical significance.

Missing Data

Smoking status was not recorded for 33 (1.6%) of the 2,060 cancer survivors. Missing data levels were less than 4.0% for all predictors except marital status for which 7.6% of the data were missing. Among the 2,027 cases with known smoking status, 1,856 had complete data; thus, 90.1% of all cancer survivors and 91.6% of cancer survivors with known smoking status were available for analysis. Multiple imputation methods for nonmonotonic categorical data, such as observed in this study, are not well developed (Fox-Wasylyshyn & El-Masri, 2005). As a result, sensitivity analyses were performed by including the missing data for each predictor as a category. Estimates for the relative likelihood of smoking differed little between analyses of respondents with complete data and analyses where missing data were included.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Demographic data for CaSurvivors, for the cancers with the highest and lowest prevalence of current smokers, and the NoCancer group are presented in Table 1. The average respondent in the CaSurvivors group was 60–69 years old, married, White, and female, with some college education and 12 years postcancer diagnosis.

Table 1.

Personal Characteristics for Cancer Survivors and NoCancer Respondents

| Cancer survivors |

|||||

| Alla | Cervical | Lymphoma | Prostrate | No cancerb | |

| n = 2,060 (%) | n = 228 (%) | n = 54 (%) | n = 245 (%) | n = 17,139 (%) | |

| Smoking*** | |||||

| Current | 18.68 | 48.32 | 9.00 | 7.46 | 21.71 |

| Former | 36.75 | 19.02 | 37.56 | 52.89 | 24.20 |

| Never | 42.74 | 31.53 | 53.44 | 36.55 | 52.30 |

| Missing | 1.83 | 1.13 | 0.00 | 3.10 | 1.79 |

| Education*** | |||||

| 1 = Less than high school | 16.86 | 14.91 | 3.08 | 22.01 | 14.38 |

| 2 = High school graduate | 32.19 | 41.69 | 49.42 | 23.62 | 28.25 |

| 3 = Some college | 26.05 | 28.49 | 26.73 | 21.15 | 30.83 |

| 4 = College graduate | 21.89 | 13.10 | 20.77 | 26.49 | 23.63 |

| Missing | 3.01 | 1.81 | 0.00 | 6.72 | 2.91 |

| Age (in years)*** | |||||

| 1 = 18–34 | 6.51 | 24.34 | 15.96 | 0.00 | 32.95 |

| 2 = 35–49 | 16.95 | 45.26 | 25.77 | 2.12 | 31.21 |

| 3 = 50–64 | 31.92 | 19.30 | 32.14 | 26.74 | 21.61 |

| 4 = 66–74 | 21.57 | 6.52 | 11.86 | 28.35 | 8.02 |

| 5 = 75+ | 22.58 | 4.41 | 14.27 | 42.08 | 5.73 |

| Missing | 0.46 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.47 |

| Marital status*** | |||||

| 1 = Married | 63.52 | 59.00 | 72.03 | 71.56 | 59.22 |

| 2 = Divorced | 11.45 | 15.59 | 6.53 | 8.18 | 8.03 |

| 3 = Widowed | 11.84 | 5.45 | 4.89 | 10.75 | 5.25 |

| 4 = Separated | 3.31 | 6.02 | 3.46 | 1.07 | 2.00 |

| 5 = Single and never married | 3.77 | 6.52 | 9.88 | 1.12 | 22.62 |

| Missing | 6.11 | 7.42 | 3.21 | 7.32 | 2.88 |

| Health access*** | |||||

| 1 = yes | 80.71 | 66.72 | 77.66 | 84.78 | 36.57 |

| 2 = partial/none | 17.51 | 31.89 | 22.34 | 12.67 | 62.12 |

| Missing | 1.78 | 1.40 | 0.00 | 2.54 | 1.31 |

| Race or ethnicity*** | |||||

| 1 = Hispanic | 5.46 | 8.69 | 3.13 | 5.33 | 12.57 |

| 2 = Black | 7.78 | 9.52 | 8.43 | 5.73 | 10.47 |

| 3 = Other | 4.55 | 7.91 | 8.97 | 2.42 | 6.43 |

| 4 = White | 77.93 | 72.15 | 79.47 | 78.24 | 66.48 |

| Missing | 4.28 | 1.73 | 0.00 | 8.28 | 4.05 |

| Gender*** | |||||

| Female | 60.82 | 100.00 | 40.01 | 0.00 | 48.94 |

| Male | 39.18 | 0.00 | 59.99 | 100.00 | 51.01 |

| Missing | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Time since diagnosis | |||||

| 1 year or less | 14.39 | 5.92 | 25.66 | 16.76 | na |

| 2–5 years | 25.00 | 12.91 | 25.97 | 43.41 | na |

| 6–10 years | 19.15 | 16.92 | 10.10 | 23.19 | na |

| 11+ years | 40.01 | 62.68 | 36.84 | 16.07 | na |

| Missing | 1.44 | 1.57 | 1.43 | 0.56 | na |

Note. Data are from the Health Information National Trends Survey surveys of 2003, 2005, and 2007. N are sample frequencies. Percentages are weighted estimates of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population.

Excludes nonmelanoma skin cancer, type of cancer not reported, or inconsistent.

Includes nonmelanoma skin cancer.

***p < .001 for comparison of cancer survivors with no cancer respondents.

Smoking Rates of Cancer Survivors

Among the 2,027 CaSurvivors, 18.7% (95% CI = 16.24–22.18) reported that they were currently smoking, which was not significantly different from the rate of 21.7% among the NoCancer respondents (n = 16,845, 95% CI = 20.91–23.34) and was close to the rates of 19.7–21.8 reported by the BRFSS for the adult population during the same period. The percentage of self-reported former smokers was significantly higher among CaSurvivors than among NoCancer respondents, 36.75% (33.95–41.05) versus 24.2% (23.63–25.68), while the percentage that reported never smoking was significantly lower, 42.74% (39.96–47.17) versus 52.3 (51.87–54.64).

Factors Affecting Smoking Rates Among Survivors

The effects among CaSurvivors of personal characteristics that affect smoking rates are shown in Table 2. Adjusting for the other factors, not having a college degree and being younger age increased the likelihood of smoking. Being divorced or widowed increased the likelihood of smoking compared with being married, and having less than full access to health care also increased the likelihood of smoking. Neither of the two largest minority racial/ethnic groups differed significantly from the majority in likelihood of smoking. Respondents in the category “other” were significantly less likely to be current smokers than Whites. No significant differences were noted between the survey years.

Table 2.

Likelihood Among Cancer Survivors of Being a Current Smoker as a Function of Personal Characteristics

| Effect | β | SE | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | T | p value |

| Intercept | −0.52 | 0.34 | −1.20 | 0.16 | −1.50 | .135 |

| Education (vs. college degree) | ||||||

| Less than high school | 0.93 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 1.55 | 3.01 | .003 |

| High school | 1.31 | 0.27 | 0.78 | 1.84 | 4.92 | <.001 |

| Some college | 0.77 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 1.27 | 3.02 | .003 |

| Age (deciles) | −0.74 | 0.10 | −0.94 | −0.54 | −7.28 | <.001 |

| Marital status (vs. married) | ||||||

| Divorced | 0.94 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 1.41 | 3.98 | .001 |

| Widowed | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 1.35 | 3.17 | .002 |

| Separated | 0.40 | 0.51 | −0.60 | 1.40 | 0.79 | .433 |

| Never married | 0.13 | 0.54 | −0.95 | 1.20 | 0.24 | .813 |

| Health access | ||||||

| None or partial vs. full | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 1.08 | 2.70 | .008 |

| Race or ethnicity (vs. White) | ||||||

| Hispanic | −0.16 | 0.42 | −0.99 | 0.67 | −0.38 | .706 |

| Black | −0.67 | 0.42 | −1.51 | 0.17 | −1.59 | .115 |

| Other | −0.94 | 0.42 | 0.12 | 1.76 | 2.25 | .026 |

| Survey year (vs. 2003) | ||||||

| 2005 | 0.17 | 0.21 | −0.25 | 0.59 | 0.79 | .428 |

| 2007 | 0.04 | 0.23 | −0.43 | 0.50 | 0.16 | .873 |

Note. n = 1,853 respondents from the Health Information National Trends Survey surveys of 2003, 2005, and 2007, weighted to reflect the noninstitutionalized U.S. adult population. Excludes nonmelanoma skin cancer and type of cancer not reported or inconsistent.

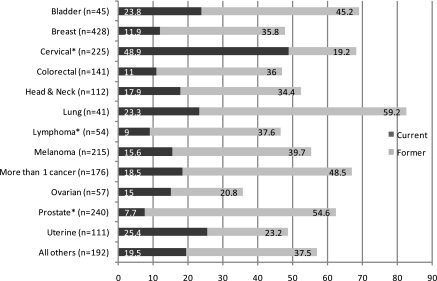

The percentages of current smokers (dark gray) and former smokers (light gray) for each type of cancer are shown in Figure 1. As can be seen, current smoking rates by cancer type varied widely and ranged from a low of 7.7% (prostate) to 48.9% (cervical). After controlling for the factors affecting likelihood of being a current smoker, cervical cancer survivors had significantly higher rates when compared with all other CaSurvivors (OR [95% CI] = 2.88 [1.66–4.73]). Survivors of lymphoma (OR [95% CI] = 0.24 [0.04–1.41]) and prostate cancer (OR [95% CI] = 0.46 [0.18–1.15]) had significantly lower rates.

Figure 1.

Current and former smoking by cancer type (%; n = 2,027). *Significant differences in smoking rate when compared with all other cancers.

Although the total sample size was the same for the comparisons of each type of cancer against the others, statistical power differs among the tests due to the different numbers of survivors for the cancer types. Differences detectable with 80% power in two-sided tests where Type I error is limited to 5% ranged from 8% to 16%, with a median detectable effect of 11%.

Limitations

This study is based on survey respondents’ accuracy in reporting their cancer diagnosis. Rauscher, Johnson, Cho, and Walk (2008) recently summarized a number of studies on the accuracy of self-report for cancer screening. However, no similar studies were found comparing self-report with medical confirmation of a cancer diagnosis. Since there were no HINTS questions about when a former smoker quit smoking, it was not possible to ascertain whether it occurred before or after their cancer diagnosis.

Cancer survivors constituted 13.4% of the HINTS sample, while the prevalence of survivors in the U.S. population is approximately 4.0% (NCI, 2010). This overrepresentation may reflect a particular interest in cancer survivors in responding to the NCI survey. However, some types of cancers were underrepresented. For example, the U.S. prevalence in 2007 was 23.0% versus 21.1% in our study for breast cancer, 20.0% versus 11.8% for prostate cancer, 10.0% versus 7% for colorectal cancer, and 9.0% versus 19.4% for gynecologic cancers. In addition, the original HINTS was designed to sample the general population and not cancer survivors (NCI, 2010). In addition, the response rates to the random digit–dial survey varied across the years and continued to decline, reflecting a national trend in phone response rates. While this may lead to population biases, the sample was adjusted statistically for nonresponse.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study of smoking behaviors among cancer survivors demonstrated that they constituted a lower proportion of current smokers, a higher proportion of former smokers, and a correspondingly lower proportion that never smoked when compared with a group without cancer. These differences largely disappeared when other factors known to influence smoking were included (namely gender, education, age, and marital status). Women with cervical cancer, however, had the highest rates of smoking, while those with lymphoma or prostate cancer had the lowest rates, even when controlling for these demographic variables.

A number of factors influenced the smoking status of the respondents: education, age, marital status, racial or ethnic identification, and access to health care. Smokers were more likely to have less than a college education, were younger, were widowed or divorced, and had no or partial health care access (either insurance or a regular provider). Some of these variables (being male, less than or equal to high school education, and being less than 65 years of age) were found also in the general U.S. population (CDC, 2009). Controlling for these variables, type of cancer was still an independent risk factor for current smoking. Survivors who had cervical cancer had the highest rates, and survivors with prostate and lymphoma had the lowest rates of smoking. These findings are similar to other studies using national databases. Bellizzi et al. (2005) found the lowest smoking rates for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors and the highest with gynecologic cancer survivors (presumably driven by cervical cancer). In another study of 802 gynecologic cancer survivors, smoking rates varied significantly by type of cancer, with cervical cancer having the highest rate (20.9%) compared with endometrial (6.1%) and ovarian (9.6%) cancers (Beesley, Eakin, Janda, & Battistutta, 2008). Smoking rates were 42% (133/315) for cervical cancer survivors in a recent Gynecologic Oncology Group study (Waggoner, Darcy, Tian, & Lanciano, 2009) in which it was found that active smokers were more likely to live with another smoker and to be exposed to smoke outside of the home.

A number of researchers have now identified cervical cancer survivors to be at high risk for smoking, at a greater rate than other cancers or the general population, which confers a poorer prognosis (Waggoner et al., 2006). These women have a significantly greater risk for secondary cancers related to both human papilloma virus (HPV) and smoking (Chaturvedi et al., 2007). This finding may be related also to clusters of high-risk health behaviors, such as drinking, smoking, and unprotected sex (leading to HPV infection), as seen in female college students (Quintiliani, Allen, Marino, Kelly-Weeder, & Li, 2009). This high-risk population should be targeted for tobacco use assessment and interventions.

Cancer survivors are at greater risk for developing new primary cancers; approximately 8% of survivors have at least one other primary cancer (Mariotto, Rowland, Ries, Scoppa, & Feuer, 2007). Many of these may be smoking related. In addition to the risk of new cancers, the quality of life of survivors is poorer for continued smokers when compared with never or former smokers (Garces et al., 2004; Pinto & Trunzo, 2005). Being diagnosed with cancer has been thought of as a teachable moment (Demark-Wahnefried, Aziz, Rowland, & Pinto, 2005) when survivors might be more receptive to health promotion and behavior change. Although we were not able to ascertain whether smoking cessation occurred before or after the diagnosis, cessation rates were high in some cancers (e.g., lung and bladder). Having cancer may increase the rate of smoking cessation; this would be an improvement since smoking rates of cancer survivors have previously been similar to the general public (Spitz, Fueger, Eriksen, & Newell, 1988).

In a qualitative study of 20 lung and head and neck cancer patients and 11 health care providers, Simmons et al. (2009) found that while many of the patients were interested in quitting, they did not ask for help, and providers were inconsistent in the type of smoking cessation information and help offered. In another study of cancer survivors (n = 1,825), only 81% of providers knew of their smoking status, and only 72.2% of current smokers (n = 310) were advised to quit smoking, missing that teachable moment (Coups, Dhingra, Heckman, & Manne, 2009). Our study found that lack of access to health care was a factor in smoking. Health disparities are often described in terms of demographic variables, but access to health care and the association with smoking rates found in this study may contribute to some of the observed disparities.

Addressing smoking cessation among current smokers in the survivor population is an important but challenging task (Gritz et al., 2006; McBride & Ostroff, 2003; Patsakham, Ripley-Moffitt, & Goldstein, 2009; Sarna et al., 2009). Using the 2005 NHIS, 1,825 cancer survivors responded to questions about smoking status and cessation efforts. Women with cervical cancer and uterine cancer reported the highest smoking rates: 42.5% and 27.1%, respectively; only 72.2% of current smokers reported being advised to quit smoking (Coups et al., 2009). Among the smokers trying to quit, only 33.8% used an evidence-based pharmacotherapy or behavioral approach and over half attempted to quit without any help. Nurses would be well situated to assess and assist with smoking cessation. However, a survey of nurses at 35 magnet-designated hospitals found that cessation interventions were suboptimal (Sarna et al., 2009).

In a recent review of smoking prevention and cessation programs for cancer survivors, sample size, target populations, types of interventions, and assessments were issues (de Moor, Elder, & Emmons, 2008). However, seven characteristics of effective cessation programs were identified: attention to health risk behaviors that may affect smoking status and cessation, designing intervention content around a theoretical framework, tailoring intervention content to survivors’ stage of readiness to quit, using peers to deliver intervention content, regular reinforcement of the importance of smoking cessation, combining nicotine replacement therapy or other drug and behavioral strategies for cessation, and delivering the high-intensity intervention over multiple sessions (de Moor et al., 2008). Reviews on the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions have been published elsewhere (Hurt, Ebbert, Hays, & McFadden, 2009). These include using evidence-based guidelines readily available from the Office of the U.S. Surgeon General to providers and other approaches to treat tobacco dependence in medical settings (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008; Hurt et al., 2009). While many cancer survivors who smoked expressed a desire to quit, they were also more reluctant to make their health care providers aware of their smoking status (Simmons et al., 2009).

Smoking rates of cancer survivors are lower than the general population, yet one of every six survivors is a current smoker. Evidence-based tobacco cessation programs should be offered to all cancer survivors who currently smoke. Current smoking rates varied by gender, education, health care access, and type of cancer. Women with cervical cancer had the highest rate of smoking compared with other cancer survivors and the general population and should be targeted for smoking cessation interventions. Health care providers, especially nurses, need to do more in creating the teachable moment by performing tobacco use assessments and implementing evidence-based smoking cessation interventions.

Funding

This work was supported by the NCI (R03CA136077). This paper is based on a poster presentation at the NCI's HINTS Data Users Conference, September 24, 2009, Silver Spring, MD.

Declaration of Interests

None Declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Carlos Melendez, M.P.H., Research Assistant.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Helping smokers quit: A guide for clinicians. 2008. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tobacco/clinhlpsmksqt.htm. [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Best practices. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.aapor.org/Best_Practices.htm. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2009. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beesley VL, Eakin EG, Janda M, Battistutta D. Gynecological cancer survivors’ health behaviors and their associations with quality of life. Cancer Causes & Control. 2008;19:775–782. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9140-y. doi:10.1007/s10552-008-9140-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Prevalence and trends data. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/ [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: Examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:8884–8893. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard C, Courneya K, Stein K. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health related quality of life: Results from the American Cancer Society's SCS-II. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation-United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Gilbert ES, Chen BE, Storm H, Lynch CF, et al. Second cancers among 104,760 survivors of cervical cancer: Evaluation of long-term risk. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99:1634–1643. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm201. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coups EJ, Dhingra LK, Heckman CJ, Manne SL. Receipt of provider advice for smoking cessation and use of smoking cessation treatments among cancer survivors. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(Suppl. 2):S480–S486. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0978-9. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coups EJ, Ostroff JS. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-0978-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, Ries LAG, Hacker DG, Edwards BK, et al. New malignancies among cancer survivors: SEER cancer registries, 1973–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006. (NIH Publication No. 05-5302) [Google Scholar]

- de Moor JS, Elder K, Emmons KM. Smoking prevention and cessation interventions for cancer survivors. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2008;24:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.006. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: Promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:5814–5830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox-Wasylyshyn SM, El-Masri MM. Handling missing data in self-report measures. Research in Nursing & Health. 2005;28:488–495. doi: 10.1002/nur.20100. doi:10.1002/nur.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garces YI, Yang P, Parkinson J, Zhao X, Wampfler JA, Ebbert JO, et al. The relationship between cigarette smoking and quality of life after lung cancer diagnosis. Chest. 2004;126:1733–1741. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1733. doi:10.1378/chest.126.6.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Mehta NV, Reece GP. Successes and failures of the teachable moment: Smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:17–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21598. doi:10.1002/cncr.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Ebbert JO, Hays JT, McFadden DD. Treating tobacco dependence in a medical setting. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009;59:314–326. doi: 10.3322/caac.20031. doi:10.3322/caac.20031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosky JL, Tyc VL, Garces-Webb DM, Buscemi J, Klesges RC, Hudson MM. Emerging issues in smoking among adolescent and adult cancer survivors: A comprehensive review. Cancer. 2007;10:2408–2419. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23061. doi:10.1002/cncr.23061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Ries LA, Scoppa S, Feuer EJ. Multiple cancer prevalence: A growing challenge in long-term survivorship. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2007;16:566–571. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0782. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer DK, Terrin NC, Menon U, Kreps GL, McCance K, Parsons SK, et al. Health behaviors in cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34:643–651. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.643-651. doi:10.1188/07.ONF.643-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CM, Ostroff JS. Teachable moments for promoting smoking cessation: The context of cancer care and survivorship. Cancer Control. 2003;10:325–333. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. HINTS final report. 2003. Retrieved from http://hints.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. HINTS final report. 2005. Retrieved from http://hints.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. HINTS final report. 2007. Retrieved from http://hints.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Estimated US cancer prevalence. 2010. Retrieved from http://dccps.nci.nih.gov/ocs/prevalence/prevalence.html#survivor. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Hesse BW, Croyle RT, Willis G, Arora NK, et al. The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS): Development, design, and dissemination. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9:443–460. doi: 10.1080/10810730490504233. discussion, 81–84. doi:10.1080/10810730490504233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsakham KM, Ripley-Moffitt C, Goldstein AO. Tobacco use and dependence treatment: A critical component of cancer care. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2009;13:463–464. doi: 10.1188/09.CJON.463-464. doi:10.1188/09.CJON.463-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto BM, Trunzo JJ. Health behaviors during and after a cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2005;104(11 Suppl.):2614–2623. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21248. doi:10.1002/cncr.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintiliani L, Allen J, Marino M, Kelly-Weeder S, Li Y. Multiple health behavior clusters among female college students. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;79:134–137. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.007. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk JA. Accuracy of self-reported cancer-screening histories: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17:748–757. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2629. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, Pollack LA, Alley LG, Zauderer LJ. Provider counseling about health behaviors among cancer survivors in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:2100–2106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6340. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Bialous SA, Wells M, Kotlerman J, Wewers ME, Froelicher ES. Frequency of nurses’ smoking cessation interventions: Report from a national survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18:2066–2077. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02796.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons VN, Litvin EB, Patel RD, Jacobsen PB, McCaffrey JC, Bepler G, et al. Patient-provider communication and perspectives on smoking cessation and relapse in the oncology setting. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.024. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz MR, Fueger JJ, Eriksen MP, Newell GR. Profiles of cigarette smoking among patients in a cancer center. Journal of Cancer Education. 1988;3:265–271. doi: 10.1080/08858198809527953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: Author, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Veneis P, Alavanja M, Buffler P, Fontham E, Franceschi S, Gao YT, et al. Tobacco and cancer: Recent epidemiological evidence. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;92:99–106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh014. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner SE, Darcy KM, Fuhrman B, Parham G, Lucci J, 3rd, Monk BJ, et al. Association between cigarette smoking and prognosis in locally advanced cervical carcinoma treated with chemoradiation: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecologic Oncology. 2006;103:853–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.017. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner SE, Darcy KM, Tian C, Lanciano R. Smoking behavior in women with locally advanced cervical carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;202 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.884. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]