Abstract

The hippocampal formation plays a pivotal role in representing the physical environment. While CA1 pyramidal cells display sharply tuned location-specific firing, the activity of many interneurons show weaker but significant spatial modulation. Although hippocampal interneurons were proposed to participate in the representation of space, their interplay with pyramidal cells in formation of spatial maps is not well understood. In this study, we investigated the spatial correlation between CA1 pyramidal cells and putative interneurons recorded concurrently in awake rats. Positively and negatively correlated pairs were found to be simultaneously present in the CA1 region. While pyramidal cell–interneuron pairs with positive spatial correlation showed similar firing maps, negative spatial correlation was often accompanied by complementary place maps, which could occur even in the presence of a monosynaptic excitation between the cells. Thus, location-specific firing increase of hippocampal interneurons is not necessarily a simple product of excitation by a pyramidal cell with a similarly positioned firing field. Based on our observation of pyramidal cells firing selectively in the low firing regions of interneurons, we speculate that the location-specific firing of place cells is partly determined by the location-specific decrease of interneuron activity that can release place cells from inhibition.

Introduction

Pyramidal cells (some of which are ‘place cells’) constitute the vast majority of neurons in the hippocampus. CA1 pyramidal neurons, which are the main output of the hippocampus (HC) aimed at entorhinal cortex and the subicular complex, tend to fire when the animal is in a particular location in the environment, its ‘place field’ or ‘firing field’ (O’Keefe & Dostrovsky, 1971; O’Keefe, 1976). This observation led to the proposal that the hippocampus is crucial for spatial coding, a theory supported by a large body of experimental (Andersen et al. 2007) and theoretical (Burgess & O’Keefe, 1996; Káli & Dayan, 2000) research.

Although interneurons constitute only 10% of all hippocampal neurons, they play a key role not only in the stabilization of the HC network (Maglóczky & Freund, 2005), but also in the precise timing of pyramidal cell activity (Somogyi & Klausberger, 2005). HC interneurons form an extremely heterogeneous population based on their morphological, neurochemical and electrophysiological properties (Freund & Buzsáki, 1996; Klausberger & Somogyi, 2008). The network of pyramidal cells and interneurons is densely interconnected, with differential contributions of the various types of interneurons (Freund & Buzsáki, 1996; Andersen et al. 2007).

While pyramidal neurons are generally considered as the basic computational units of the hippocampus (Yamaguchi et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2009), interneurons are thought to provide a general framework for network synchronization and to prevent overexcitation (Freund & Buzsáki, 1996; Maglóczky & Freund, 2005). Although a role of interneurons in spatial coding has been suggested based on the observation that location-specific decrease of interneuron firing can carry similar amounts of spatial information to pyramidal cell firing fields (Wilent & Nitz, 2007), how interneurons and pyramidal cells act together in representing the environment remains elusive. Here we show that pyramidal cell–interneuron pairs can exhibit similar (positively correlated) or complementary (negatively correlated) spatial firing maps. Both types of correlation occurred in the presence or in the absence of a putative monosynaptic excitatory connection between the neurons, and no relationship between the spatial and the temporal correlations could be detected. Thus, the spatial specificity of interneuron firing is not necessarily a direct correlate of the firing fields of place cells giving input to the interneuron. Rather, we suggest bidirectional interplay between pyramidal cells and interneurons in determining location-specific firing rate changes of hippocampal neurons.

Methods

Animal handling

Adult male Long Evans rats (n = 16) weighing 300–350 g before surgery were used for the present study. Rats were kept in individual cages on a 12:12 h light–dark cycle. All animal procedures were approved by the University of Bristol Ethical Review Committee, performed in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and complied with guidelines for animal experimentation published in the National Institute of Health publication Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals as well as The Journal of Physiology's policies on animal experimentation (Drummond, 2009). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used.

Behavioural methods

Recording sessions were 16–18 min long. Hungry rats (deprived to 85%ad libitum weight) chased 25 mg food pellets randomly scattered at ∼3 min−1 into a 76 cm diameter cylinder with a 45 deg cue card pasted on its wall. The cylinder was surrounded by a 2 m diameter dark circular curtain for visual isolation and it was centred in a 3.0 m × 3.0 m sound-attenuated room. Lighting was provided by eight 40 W bulbs evenly spaced at the perimeter of a 1 m diameter disc suspended 2 m above the cylinder floor. During pellet chasing sessions, rats were tracked at 25 Hz with an overhead TV camera.

Surgery

Surgical procedures, electrode preparation, and implantation methods have been described previously (Muller et al. 1987; Fenton et al. 2000; Rivard et al. 2004; Huxter et al. 2007). See also Supplemental Methods for a description.

Recordings

The electrodes were slowly advanced (60 μm per day) until they reached CA1 stratum oriens, as judged by the appearance of clear rhythmic activity in the 5–12 Hz theta band during walking, large amplitude sharp waves during immobility and detection of relatively large (>100 μV) action potential waveforms. Subsequently, recordings were made during pellet chasing. Spike activity was recorded from the four tetrodes and LFP activity (available in 10 of 16 rats) was separately recorded from the same 16 channels with different filter settings. Extracellular action potentials were captured at 30 kHz for 32 samples (1.07 ms) on each wire of a tetrode whenever the amplitude on any wire exceeded a 100 μV threshold; filtering was between 300 Hz and 6000 Hz. The 16 tetrode wires (4 wires per tetrode) were also used to continuously record local EEG digitized at 5 kHz; filtering was between 1 Hz and 475 Hz (Fig. 1).

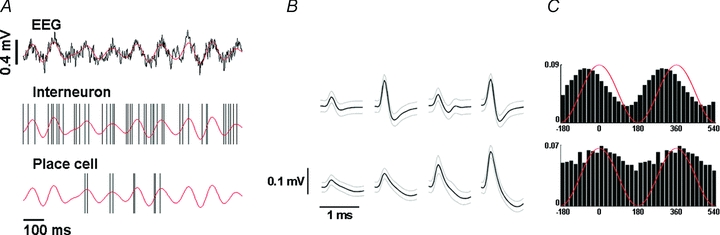

Figure 1. Demonstration of a raw EEG trace and concurrent action potential firing.

A, raw EEG trace (upper panel) shows hippocampal theta oscillation. Filtered (4–12 Hz) signal is superimposed in red. Concurrent recordings of a hippocampal interneuron (middle panel) and a place cell (lower panel) are demonstrated. Black vertical lines indicate the time instances of action potential firing. Filtered EEG trace is replicated (red) for visualization purposes. Positive spatial correlation exhibited by this pair is demonstrated in Fig. 5B. B, average action potential waveforms from the four tetrode wires. Black line, mean waveform; grey lines, s.d. of the waveforms. Upper, interneuron; lower, place cell. C, firing phase of the neurons relative to the hippocampal theta oscillation. Idealized theta cycles are superimposed in red (two cycles are shown). The interneuron (upper) shows higher firing rates associated to the rising phase of hippocampal theta, whereas the place cell shows weak phase-locking to theta peaks.

Data analysis

Spike sorting

Spikes captured during pellet chasing were sorted into clusters (presumptive single cells) on the basis of their spike amplitude and wave shape on the tetrode channels. See Supplemental Methods for a detailed description. Putative interneurons and pyramidal cells were differentiated based on their average firing rates and firing patterns (firing rate of interneurons, mean ±s.d., 25.72 ± 10.59 Hz; firing rate of pyramidal cells, mean ±s.d., 1.85 ± 1.01 Hz). The two cell classes showed clearly separated ranges of mean firing rate (interneurons, range, 11.83–54.70 Hz; pyramidal cells, range, 0.36–4.76 Hz). Place cells generate long silent intervals when the head of the animal is outside the firing field, whereas interneurons never cease firing completely. In addition to average firing rate, a cell was considered an interneuron only if it never showed protracted (>3 s) silent intervals during pellet chasing (longest silent interval for interneurons, mean ±s.d., 1.18 ± 0.56 s, range, 0.46–2.45 s; longest silent interval for pyramidal cells, mean ±s.d., 18.45 ± 11.12 s, range, 4.30–46.79 s). We calculated extracellular spike widths at 1/e of peak amplitude to further confirm our separation (inteneurons, mean ±s.d., 153.42 ± 32.69 μs; pyramidal cells, mean ±s.d., 228.12 ± 39.00 μs).

Spatial firing patterns

The arena was split into spatial bins (2.9 cm on a side) and the number of action potentials fired in each bin as well as the occupancy of the bins was calculated. Spatial firing distributions were computed by dividing occupancy into action potential number for each bin. Bins where the rat spent less than 0.25 s and bins with less than four visits were excluded. Both firing rate maps and occupancy maps were smoothed by a Gaussian kernel over the surrounding 3 × 3 bins (s.d., 0.65 bin = 1.9 cm).

Spatial correlation

Spatial correlation was calculated as two-dimensional linear correlation between the spatial firing patterns. Spatial bins where the firing rate of both neurons was lower than 20% of the corresponding peak firing activity were omitted from the calculation to prevent artificial distortion of linear correlations by near-zero values. However, omission of this threshold did not alter the correlation values substantially (Supplemental Table 2).

Complementarity index (CI)

Let Pp and Pi denote the pyramidal cell and interneuron ‘firing fields’. Pi and Pp are the sets of spatial bins such that the rate in a bin is >0.5 of the firing rate in the peak bin. A is the entire arena. |·| denotes set size and the minus operator between sets is the set theoretical difference.

The first addend quantifies disjunctiveness (non-overlapping property), since it is the proportion of the pyramidal cell firing field not covered by the firing field of the interneuron. The second addend is the proportion of the arena pixels covered by the pyramidal cell field, after subtracting the interneuron field. Thus, the second addend measures how well the arena is covered. (Subtraction of the interneuron field is necessary; otherwise the size difference between interneuron and principal cell firing fields reduces the sensitivity of the covering measure.) Thus, CI = 1 implies fully disjunct firing fields that together cover the entire arena, whereas a low CI value indicates largely overlapping place fields.

Auto- and cross-correlation

Autocorrelations of unit firing were calculated from −200 to 200 ms time lags with 4 ms bin size. Cross-correlations of pyramidal cell and interneuron firing were calculated at two different resolutions (from −50 to 50 ms with 1 ms bin size and from −5 to 5 ms with 0.5 ms bin size) and expressed as probabilities. The cross-correlations were taken with reference to the pyramidal cell so that a peak after zero means that interneuron firing followed pyramidal cell firing. Normalized cross-correlations were calculated based on Marshall et al. (2002) to assess putative monosynaptic excitatory connection between hippocampal neurons (see Supplemental Methods for details). While it is feasible to detect monosynaptic excitatory connections with high fidelity based on cross-correlation, the detection of putative inhibitory synapses has severe technical limitations. First, whereas excitation is capable of causing a severalfold increase in firing rate (see Fig. 2B), inhibition has a limited range of effect constrained by basal firing levels. Second, spike sorting from tetrode recordings has a tendency to miss spikes when occurring close to an action potential from another neuron, which can lead to false detection of monosynaptic inhibition (Harris et al. 2000).

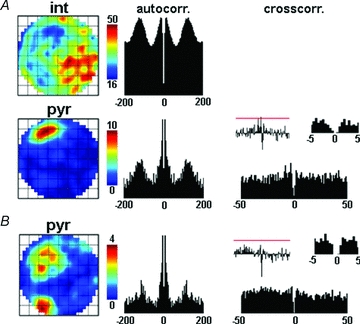

Figure 2. Examples of negative spatial correlation between place cells and interneurons.

A, representative example of a pyramidal cell–interneuron pair showing negative spatial correlation (R = −0.59). Upper left, interneuron rate map (blue colour is associated to the lowest firing rate); middle, interneuron autocorrelation. Lower left, pyramidal cell rate map; middle, pyramidal cell autocorrelation. Right, cross-correlation of place cell and interneuron firing, with reference to the pyramidal cell. Left inset shows normalized cross-correlogram (see Methods); red line indicates the level of significant interaction at P = 0.0013. Right inset shows the centre of the cross-correlogram at higher temporal resolution. The absence of a significant peak within 3 ms from the centre indicates the lack of functional monosynaptic excitation of the interneuron by the pyramidal cell. B, another example of a negatively correlated pair of an interneuron and a place cell (R = −0.41). Panels are arranged as in A. The significant short latency peak in the cross-correlogram implies monosynaptic coupling of the cells. Firing field complementarity is seen for both pairs (CI = 0.66 for neurons in A, CI = 0.58 for neurons in B).

Phase calculations

Hippocampal local field potential (LFP) was filtered in the theta band (4 to 12 Hz). The instantaneous theta phase of the LFP was calculated by the Hilbert-transform method applied to the filtered signal (Hurtado et al. 2004). Cycles were detected as data segments between pi-crossings of the phase series. Cycles with length falling out of the theta range and those with a low LFP amplitude (< mean + 2 s.d.) were discarded from further analysis (see also Supplemental Notes and Supplemental Fig. 2). Phase distributions for interneurons were calculated from the LFP phase values at the locations of action potentials. These distributions were characterized by the circular mean and the mean vector length. The mean vector length quantifies the spread around the mean (0, high variation of phase values; 1, perfect phase preference) (Fisher, 1993). For group statistics, randomly chosen values (5000 for interneurons and 500 for place cells) from individual phase distributions were pooled to get a balanced sample. Only neurons with significant phase locking were included (P > 0.001, Rayleigh's test for uniformity; Fisher, 1993). Phase distributions were compared by two samples Watson's test for homogeneity on the circle.

The analysis was carried out in Matlab development environment using custom-built and built-in functions (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Fisher's exact test was performed in Statistica (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Coupling between neighbouring cells

We analysed 370 interneuron–place cell pairs recorded from 16 freely moving rats. Of these pairs, 170 were recorded from the same tetrode and the remainder from different tetrodes. We found that 12/170 pairs (7.1%) on the same tetrode showed a strong negative spatial correlation but only 3/200 pairs (1.5%) on different tetrodes were negatively correlated. Similarly, 14/170 pairs (8.2%) on the same tetrode had a positive correlation whereas only 3/200 pairs (1.5%) on different tetrodes were positively correlated. The probability that the proportions of highly correlated cells is the same for pairs on the same and different tetrodes is 0.0079 for negative correlations and 0.0023 for positive correlations (Fisher's exact test). Thus, clear interactions are much more likely for interneuron–pyramidal cell pairs that are likely to be neighbours. The low probability of coupling among more distant neurons also sets an upper bound on spurious occurrence of spatial correlations.

Negative spatial correlation between hippocampal interneurons and pyramidal cells

In general, when there was a significant negative correlation between the place cell and interneuron spatial firing patterns, it was easy to see complementarity by inspection of corresponding rate maps (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 2). We quantified this finding using the spatial complementarity index (CI) based on high firing rate regions from both members of a pair (see Methods). High CI values were characteristic of most of the negatively correlated pairs (see Supplemental Table 2. CI = 0.66 for the pair in Fig. 2A; CI = 0.58 for the pair in Fig. 2B).

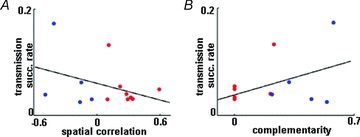

Negative spatial correlations occurred in both the absence (10/15; Fig. 2A) and the presence (5/15; Fig. 2B) of presumed excitatory monosynaptic connections from pyramidal cells to interneurons. Furthermore, there was no significant relationship between either the spatial correlation or CI and the transmission success rate at the putative excitatory synapse (Fig. 3). This implies that the excitatory influence of the pyramidal cell was not sufficient to cause positively correlated spatial firing in the innervated interneuron.

Figure 3. Transmission success rate was not correlated with either spatial correlation or complementarity index.

A, scatter plot showing the relationship of spatial correlation and transmission success rate for those pairs in which a monosynaptic connection between the place cell and the interneuron was established. The blue dots are for pairs with negative spatial correlation; the red dots are for pairs with positive spatial correlation. The two variables were not correlated significantly (P = 0.23). B, relationship between complementarity index and transmission success rate. The colour coding of A applies. Again, there was no significant correlation between the two parameters (P = 0.14).

Interestingly, we also observed interneurons whose discharge was negatively correlated with two different pyramidal cells (n = 4). In these cases, the place cell fields could occupy different low firing regions of the interneuron (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Example of an interneuron with two negatively correlated place cells.

A, an interneuron–pyramidal cell pair with negative spatial correlation (R = −0.39) is presented. Panel arrangement of Fig. 2 applies also for this figure. The lack of significant short latency peak on the cross-correlogram indicates that no monosynaptic excitation between the neurons was present. B, firing characteristics of a place cell showing negative spatial correlation with the same interneuron (R = −0.41). This neuron was also not coupled to the interneuron monosynaptically. The place cell in A fired in only one of those two areas of the arena where the firing rate of the interneuron was low. In contrast, pyramidal cell in B showed two place fields corresponding to the locations characterized by low interneuron activity.

Positive spatial correlation between hippocampal interneurons and pyramidal cells

Monosynaptic excitation of a hippocampal interneuron by a place cell can be accompanied by a positive correlation between the spatial firing patterns of the two neurons (Marshall et al. 2002). In agreement, we observed interneuron–place cell pairs with positive spatial correlations for which there was putative monosynaptic excitation of the interneuron by the pyramidal cell (8/17 pairs with positive spatial correlation; Fig. 5B, Supplemental Table 2). However, positive spatial correlations could also be detected in the absence of functional short latency excitation (9/17; Fig. 5A). Additionally, the degree of spatial correlation between interneuron firing and place cell firing was not correlated with the transmission success rate of the monosynaptic excitation (Fig. 3).

Figure 5. Examples of positive spatial correlation between pyramidal cells and interneurons.

A, representative example of a place cell–interneuron pair with positively correlated place maps (R = 0.21). Arrangement of panels of Fig. 2 applies. The absence of a short latency peak in the cross-correlogram indicates that the cells are not coupled by monosynaptic excitatory connection. B, a second pyramidal cell–interneuron pair with a positive spatial correlation (R = 0.32). The significant peak of the cross-correlation within 3 ms from the centre indicates monosynaptic excitation of the interneuron by the pyramidal cell. The overlap of the high rate regions for both interneuron–pyramidal cell pairs is shown by the low complementarity indices (CI = 0 for neurons in A and B).

We also observed four cases in which an interneuron showed both positive and negative correlations with different pyramidal cells showing that the populations of interneurons forming positive and negative spatial correlation with place cells overlap at least partially.

Phase analysis of hippocampal interneurons

The diversity of hippocampal interneurons is also reflected in distinct phase preferences of different interneuron types relative to the ongoing hippocampal theta oscillation (Freund & Buzsáki, 1996; Klausberger & Somogyi, 2008). Perisomatic inhibitory cells mainly fire at the peak of the theta oscillation recorded in the pyramidal layer (0 degree), whereas interneurons targeting dendrites tend to be active around the theta trough (180 deg). Thus, analysis of preferred phases suggests the identity of the recorded interneurons.

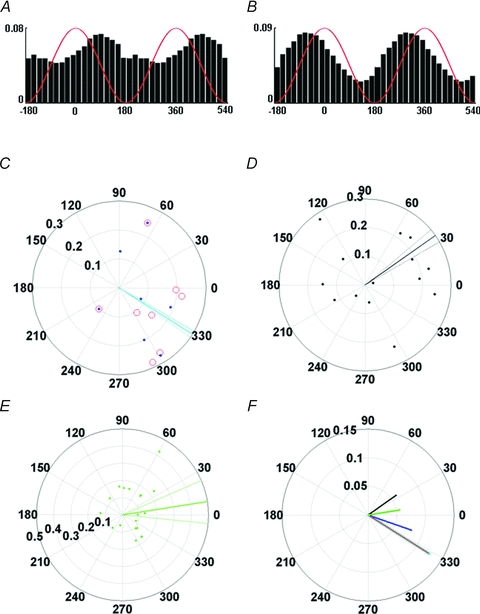

We investigated the mean phases of 14 interneurons with positive or negative spatial correlations with place cells for which the hippocampal LFP was available (Fig. 6). Of the 14 interneurons, 13 exhibited significant phase locking to the hippocampal theta rhythm. Regardless of the sign of correlation, most of the interneurons showed a preference for angles on the positive phase of theta oscillations; the preferred angle could be on the rising (Fig. 6B) or descending (Fig. 6A) portion of the cycle near the positive peak (mean phase, 327.6 deg; mean vector length, 0.128). To test whether the interneurons with correlated place cell pairs are different from a random selection, we calculated theta phase for an additional 15 interneurons recorded from the same animals, but for which no correlated place cell was detected (14/15 phase coupled to hippocampal theta). The preferred phases of these interneurons distributed around the peak and the trough of the theta cycle (Fig. 6D, and so had a significantly different distribution from interneurons showing positive or negative spatial correlation with pyramidal cells, P < 0.001, Watson's test). In summary, although firing phase analysis does not provide an unequivocal identification of interneuron types, a series of studies performed mostly by Klausberger and colleagues (Klausberger et al. 2003; Somogyi & Klausberger, 2005; Klausberger & Somogyi, 2008; Klausberger, 2009) show that the preferred theta phases of interneurons forming correlated pairs with pyramidal cells resemble those of perisomatic inhibitory neurons, that is basket cells and axo-axonic cells.

Figure 6. Phase relationship of interneurons to hippocampal theta oscillation.

A, phase histogram of a representative interneuron participating in negatively correlated place cell–interneuron pairs (the one shown in Fig. 2A). Idealized theta cycles are superimposed in red (two cycles are shown). The interneuron is phase locked to the descending slope of the theta oscillation. B, phase histogram of the interneuron shown in Fig. 5B, participating in a positively correlated place cell–interneuron pair. Phase coupling to the rising slope of hippocampal theta is clearly visible. C, phase value distribution of each interneuron's action potential series, in which hippocampal LFP was recorded concurrently, is presented on a polar plot. In the figure, every mark represents an interneuron (blue dot, interneuron with negatively correlated place cell pair; red circle, interneuron with positively correlated pyramidal cell pair; blue dot in red circle, interneuron that participated in both type of pairs). Localization on the circle shows mean phase (zero phase represents the peak of theta oscillation), whereas distance from the centre indicates mean vector length (longer distance from centre means stronger phase coupling). The thick cyan bar represents population phase of interneurons with any type of place cell pairs; thin cyan lines indicate 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Most of the interneurons (12/13, 92%) were phase-locked to the positive phase of the theta cycle. D, phase locking of interneurons recorded from the same animals but without a detected place cell pair. The thick black bar indicates population mean and the thinner black lines in its close vicinity show 95% confidence intervals. Mean phase values occupy a domain of the unit circle that is different from that of the interneurons with correlated pairs of place cells in panel A (P < 0.001, Watson's test). Mean directions fall to the positive (9/14, 64%) or the negative phase (5/14, 36%) of hippocampal theta. E, phase locking of pyramidal neurons. Green lines indicate population mean and 95% confidence intervals. Although pyramidal neurons are coupled to the negative phase of theta oscillation in anaesthetized animals (Klausberger et al. 2003), preferred phases of principal cells recorded from freely moving rats could occupy any position on the unit circle. This difference is probably according to the modification of the preferred theta phase by the phase precession, which can result pyramidal cell firing at any particular theta phase (Schmidt et al. 2009). F, mean phase of interneurons with negatively correlated pairs (red), positively correlated pairs (blue), any type of pairs (cyan), interneurons without a detected place pair (black) and pyramidal cells (green). Lengths of the bars indicate mean vector length. Width of the cyan bar was increased to improve the visualization of the overlapping cyan and red bars. Note the different scaling of the polar plots in panels C–F.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that place cell–interneuron pairs with similar and complementary spatial firing patterns coexist in the hippocampus. Surprisingly, complementary rate maps were observed even in the presence of a monosynaptic excitatory connection between the pyramidal cell and the interneuron, suggesting that inhibitory processes also participate in the generation of spatial maps. While previous studies propose that the spatial modulation of interneuron firing is inherited passively from the place cells, that is it merely reflects spatial tuning of pyramidal cells that give rise to the inputs of the interneurons (Marshall et al. 2002; Maurer et al. 2006), our results suggest that there could be a more complicated interplay between the interneurons and pyramidal cells in the hippocampal ‘spatial network’. Thus, we suggest that interneurons should be considered in future hippocampus models as active participants in the computations.

A key issue of cortical information processing yet to be resolved is whether inhibitory neurons may participate in the representation of information besides their well-known function of orchestrating principal cell activity. Recent studies (Wilent & Nitz, 2007; Ego-Stengel & Wilson, 2007) support this possibility by demonstrating that interneurons can exhibit similar degrees of location specificity and spatial resolution as pyramidal cells. Moreover, location-specific decreases of firing rate in interneurons (‘OFF’ fields) carrying similar amounts of spatial information as place cell firing fields were also detected. Wilent & Nitz (2007) discuss that the location-specific firing of place cells may partly be determined by the location-specific decrease of interneuron activity that can release place cells from inhibition. Our observation of pyramidal cells firing selectively in the ‘OFF’ field of interneurons strongly supports this view. We also observed interneurons with multiple ‘OFF’ fields possibly representing hubs capable of determining the place fields of multiple place cells. Moreover, in some cases, place cells with multiple fields were also matched with interneurons having multiple ‘OFF’ fields implying inhibitory shaping of complex spatial representations (Fig. 4).

Effective inhibition of place cell output can be conveyed by basket and axo-axonic cells. The mean firing phase of interneurons participating in negatively correlated pairs relative to theta oscillations was 341 deg, similar to the average phases of basket and axo-axonic cells (Klausberger & Somogyi, 2008). However, sampling bias towards these interneuron types, which are often fast spiking and thus might be easier to detect, cannot be completely ruled out, although interneurons recorded from the same animals but without correlated pairs of place cells showed a slightly different phase distribution pattern (Fig. 6). Additionally, since firing phase analysis does not provide an unequivocal identification of hippocampal interneurons, it is possible that some of the interneurons with spatially correlated place cell pairs belong to dentritic targeting (e.g. bistratified, trilaminar) interneuron subgroups. Additionally, GABAergic cells of deep radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare (SL-M) that inhibit basket and axo-axonic cells might also play a role in the formation of correlated spatial firing maps. Recruitment of these interneurons by SL-M stimulation produced GABAA,slow IPSCs in CA1 pyramidal cells and reduced the amplitude and frequency of GABAA,fast spontaneous IPSCs for several hundred milliseconds probably through the inhibition of putative basket and axo-axonic cells as well as pyramidal neurons (Banks et al. 2000). This ‘suppression of fast inhibition’ not only had a time course appropriate for theta frequency modulation (Banks et al. 2000) but also could be a putative mechanism for the explanation of the observed complementary spatial firing maps. The identity of the interneurons activated by the SL-M stimulation is not known, but based on their anatomical localization and the kinetics of the IPSCs they evoke, these interneurons are likely to be neurogliaform cells or ivy cells (Klausberger, 2009).

Besides negatively correlated pairs, interneuron–place cell pairs with positive spatial correlation were also found. Monosynaptic excitation from a pyramidal cell resulting in a location-specific increase of interneuron firing was suggested as a basis for such positive spatial correlations (Marshall et al. 2002; Maurer et al. 2006). However, positively correlated pairs lacking excitatory coupling were also found. This implies that in addition to monosynaptic excitation, place field similarity can be formed by more complex network interactions that probably involve inhibitory processes as well. Accordingly, the place cell might be disinhibited by the interneuron through another inhibitory neuron, a type of connectivity which is common in the hippocampal formation (Freund & Buzsáki, 1996; Ji & Dani, 2000). Alternatively, a synchronously active place cell population may drive a set of interneurons, but not every pyramidal cell from the co-active assembly is connected to the driven interneuron (Marshall et al. 2002; Harris et al. 2003). These interneurons may prevent the activity of other place cell assemblies, which could result in negative spatial correlation. Importantly, interneurons forming positively and negatively correlated pairs simultaneously were observed showing that the two mechanisms involve overlapping anatomical groups.

Clear interactions were more common among neurons that were likely to be in close vicinity. Taking the spatial limitations of extracellular recordings into account (Henze et al. 2000; Cohen & Miles, 2000), neurons recorded by the same electrode might have been located within 100 μm from each other, whereas pairs from different electrodes are presumably at least 300 μm apart. The drop in interaction probability with distance can be accounted for by several reasons: (1) limited range of pyramidal cell local axon collaterals and interneuron dendritic arbours (several hundred microns along the septo-temporal axis depending on the interneuron type, e.g. 200–500 μm in parvalbumin-positive basket cells, 300–800 μm in calbindin-positive interneurons, 700–800 μm in hippocampo-septal neurons; Gulyás et al. 1999; Buhl & Whittington, 2007; Takács et al. 2008); (2) pyramidal cells may preferentially synapse on dendrites in the vicinity of the somata of neighbouring interneurons indicated by the higher density of axon collaterals and synaptic boutons of pyramidal cells near the cell bodies (Csicsvari et al. 1998); and (3) distal axon branches targeting distal dendritic segments may have higher conductance failure and are consequently harder to detect (Csicsvari et al. 1998). Similar spatial bias of connection probability was reported in the neocortex (Fujisawa et al. 2008), suggesting that preferential connection of neighbouring cells is a general organizational principle of cortical networks.

One possible scenario of microcircuit interactions that can lead to the observed types of pairs is a three synapse pathway involving two interneurons between two place cells (i.e. a place cell 1–interneuron 1–interneuron 2–place cell 2 path; Supplemental Fig. 3A). In this case, the two place cells and interneuron 1 would have similar place fields, whereas interneuron 2 would show complementary spatial firing. Thus, interneuron 1 would exhibit a positive spatial correlation with both place cells, although the monosynaptic connection links it only to place cell 1; interneuron 2 would show a negative spatial correlation with both pyramidal cells. Additionally, interneuron 2 may also inhibit pyramidal cell 1, forming a closed loop (Supplemental Fig. 3B).

However, it should be emphasized that the above model is by necessity oversimplified and does not consider convergence and divergence in hippocampal circuitry and differences in the connectivity of various types of interneurons.

In summary, we have demonstrated that place cell–interneuron pairs with similar and complementary spatial firing are simultaneously present in the hippocampus of freely moving rats. Both type of spatial relationship could occur either in the presence or in the absence of putative excitatory connections between the cells. These findings suggest that spatial organization of interneuron firing is not a simple product of their excitatory inputs but more complicated interactions involving both inhibitory and excitatory processes are responsible for the determination of spatial properties of firing in the hippocampus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie Milkins for electronics and engineering support and Bruno Rivard for developing and manufacturing the microdrives. We thank John R. Huxter for kindly providing additional data for the analysis. We thank Edit Papp for helping to establish the collaboration between B.H. and A.C. We thank Viktor Varga, Péter Barthó, Attila Gulyás and György Buzsáki for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) and NIH grant NS20686.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CA

cornu ammonis

- CI

complementarity index

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- HC

hippocampus

- LFP

local field potential

- SL-M

stratum lacunosum-moleculare

Author contributions

A.C. and R.U.M. designed the project, A.C. conducted the experiments, and B.H. and Y.L. analysed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and the preparation of the manuscript and approved the final version. All experiments were done in the Department of Anatomy, University of Bristol, Medical School, Bristol, UK.

References

- Andersen P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O’Keefe J. The Hippocampus Book. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Banks MI, White JA, Pearce RA. Interactions between distinct GABAA circuits in hippocampus. Neuron. 2000;25:449–457. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80907-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N, O’Keefe J. Neuronal computations underlying the firing of place cells and their role in navigation. Hippocampus. 1996;6:749–762. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:6<749::AID-HIPO16>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl E, Whittington M. Local circuits. In: Andersen P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O’Keefe J, editors. The Hippocampus Book. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 297–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen I, Miles R. Contributions of intrinsic and synaptic activities to the generation of neuronal discharges in in vitro hippocampus. J Physiol. 2000;524:485–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Czurko A, Buzsáki G. Reliability and state dependence of pyramidal cell-interneuron synapses in the hippocampus: an ensemble approach in the behaving rat. Neuron. 1998;21:179–189. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ego-Stengel V, Wilson MA. Spatial selectivity and theta phase precession in CA1 interneurons. Hippocampus. 2007;17:161–174. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton AA, Csizmadia G, Muller RU. Conjoint control of hippocampal place cell firing by two visual stimuli. II. A vector-field theory that predicts modifications of the representation of the environment. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:211–221. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher N. Statistical Analysis of Circular Data. Cambridge: Cambridge Univerity Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Buzsáki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa S, Amarasingham A, Harrison MT, Buzsáki G. Behavior-dependent short-term assembly dynamics in the medial prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nn.2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulyás AI, Megías M, Emri Z, Freund TF. Total number and ratio of excitatory and inhibitory synapses converging onto single interneurons of different types in the CA1 area of the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10082–10097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-10082.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Dragoi G, Buzsáki G. Organization of cell assemblies in the hippocampus. Nature. 2003;424:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature01834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD, Henze DA, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Buzsáki G. Accuracy of tetrode spike separation as determined by simultaneous intracellular and extracellular measurements. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:401–414. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze DA, Borhegyi Z, Csicsvari J, Mamiya A, Harris KD, Buzsáki G. Intracellular features predicted by extracellular recordings in the hippocampus in vivo. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:390–400. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Brandon MP, Griffin AL, Hasselmo ME, Eden UT. Decoding movement trajectories through a T-maze using point process filters applied to place field data from rat hippocampal region CA1. Neural Comput. 2009;21:3305–3334. doi: 10.1162/neco.2009.10-08-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado JM, Rubchinsky LL, Sigvardt KA. Statistical method for detection of phase-locking episodes in neural oscillations. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1883–1898. doi: 10.1152/jn.00853.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxter JR, Zinyuk LE, Roloff EL, Clarke VR, Dolman NP, More JC, Jane DE, Collingridge GL, Muller RU. Inhibition of kainate receptors reduces the frequency of hippocampal theta oscillations. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2212–2223. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3954-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D, Dani JA. Inhibition and disinhibition of pyramidal neurons by activation of nicotinic receptors on hippocampal interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2682–2690. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Káli S, Dayan P. The involvement of recurrent connections in area CA3 in establishing the properties of place fields: a model. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7463–7477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07463.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T. GABAergic interneurons targeting dendrites of pyramidal cells in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:947–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Magill PJ, Márton LF, Roberts JD, Cobden PM, Buzsáki G, Somogyi P. Brain-state- and cell-type-specific firing of hippocampal interneurons in vivo. Nature. 2003;421:844–848. doi: 10.1038/nature01374. Erratum in: Nature 441, 902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science. 2008;321:53–57. doi: 10.1126/science.1149381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglóczky Z, Freund TF. Impaired and repaired inhibitory circuits in the epileptic human hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L, Henze DA, Hirase H, Leinekugel X, Dragoi G, Buzsáki G. Hippocampal pyramidal cell-interneuron spike transmission is frequency dependent and responsible for place modulation of interneuron discharge. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-j0001.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer AP, Cowen SL, Burke SN, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Phase precession in hippocampal interneurons showing strong functional coupling to individual pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13485–13492. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2882-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Kubie JL, Ranck JB., Jr Spatial firing patterns of hippocampal complex-spike cells in a fixed environment. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1935–1950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01935.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J. Place units in the hippocampus of the freely moving rat. Exp Neurol. 1976;51:78–109. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely moving rat. Brain Res. 1971;34:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivard B, Li Y, Lenck-Santini PP, Poucet B, Muller RU. Representation of objects in space by two classes of hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:9–25. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R, Diba K, Leibold C, Schmitz D, Buzsáki G, Kempter R. Single-trial phase precession in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13232–13241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2270-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Defined types of cortical interneurone structure space and spike timing in the hippocampus. J Physiol. 2005;562:9–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takács VT, Freund TF, Gulyás AI. Types and synaptic connections of hippocampal inhibitory neurons reciprocally connected with the medial septum. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:148–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilent WB, Nitz DA. Discrete place fields of hippocampal formation interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:4152–4161. doi: 10.1152/jn.01200.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Sato N, Wagatsuma H, Wu Z, Molter C, Aota Y. A unified view of theta-phase coding in the entorhinal-hippocampal system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]