Abstract

Activation of vascular adrenoreceptors (ARs) governs the magnitude and distribution of muscle blood flow in accord with the distribution of AR subtypes. Functional studies in the rat cremaster muscle indicate that α1ARs predominate in proximal arterioles (first-order, 1A) while α2ARs predominate in distal arterioles (third-order, 3A). However, little is known of AR subtype distribution in arteriolar networks of locomotor skeletal muscles, particularly in the mouse. We tested the hypotheses that functional AR subtypes exhibit heterogeneity among branches of arteriolar networks in a locomotor muscle and that the nature of this heterogeneity can vary between muscles having diverse functions. In anaesthetized male C57BL/6J mice (3 months old), concentration–response curves (10−9m to 10−5m, 0.5 log increments) were evaluated in the gluteus maximus muscle superfused with physiological saline solution (35°C, pH 7.4; n ≥ 5 per group). Noradrenaline (NA, non-selective αAR agonist) constricted 1A, 2A and 3A with similar potency and efficacy. Phenylephrine (PE; α1AR agonist) evoked greater (P < 0.05) constriction in 3A (inhibited by 10−8m prazosin; α1AR antagonist) while UK 14304 (UK; α2AR agonist) evoked greater (P < 0.05) constriction in 1A (inhibited by 10−7m rauwolscine; α2AR antagonist). Isoproterenol (isoprenaline; βAR agonist) dilated 1A, 2A and 3A near-maximally with similar potency and efficacy; these dilatations were inhibited by 10−7m propranolol (βAR antagonist) which otherwise had no effect on responses to NA, PE, or UK. Complementary experiments in the mouse cremaster muscle revealed a pattern of αAR subtype distribution that, while distinct from the gluteus maximus muscle, was consistent with that reported for the rat cremaster muscle. We conclude that functional αAR subtype distribution in arteriolar networks of skeletal muscle varies with muscle function as well as vessel branch order.

Introduction

Vascular adrenoreceptors (ARs) are integral to the regulation of arterial blood pressure through adjustments in peripheral resistance. Sympathetic nerve activity releases noradrenaline (NA) from perivascular sympathetic nerve terminals (Luff, 1996) to elicit vasoconstriction and thereby restrict blood flow. In the microcirculation, neurovascular coupling is mediated through activating post-junctional αARs on arteriolar vascular smooth muscle cells, with functional α1AR and α2AR subtypes shown in animals and humans (Medgett & Langer, 1984; Flavahan et al. 1987; Faber, 1988; Aaker & Laughlin, 2002; Wray et al. 2004; Lambert & Thomas, 2005; Jackson et al. 2008). The magnitude of vasoconstriction in response to sympathetic nerve stimulation varies among arterioles differing in size and branch order. For resistance networks of skeletal muscle, sympathetic nerve stimulation evokes greater constriction in smaller arterioles located downstream when compared to larger arterioles and feed arteries located upstream (Folkow et al. 1971; Rosell, 1980; Marshall, 1982; Boegehold & Johnson, 1988; Ohyanagi et al. 1991; VanTeeffelen & Segal, 2003). Further, distal arteriolar branches exhibit greater ‘escape’ from constriction in resting muscle and more readily dilate (i.e. exhibit functional sympatholysis) during skeletal muscle contraction (Folkow et al. 1971; Marshall, 1982; Boegehold & Johnson, 1988; Anderson & Faber, 1991; VanTeeffelen & Segal, 2003). Thus, dilatation of distal arterioles effectively maximizes capillary perfusion and the functional surface area for exchange between microvessels and parenchymal cells while proximal arterioles and feed arteries remain constricted (and restrict muscle blood flow) to maintain systemic perfusion pressure (Folkow et al. 1971; Segal, 2000; Thomas & Segal, 2004).

The differential distribution of α1AR and α2AR subtypes has been used to explain why distal arterioles more readily undergo functional sympatholysis during muscle contraction when compared to proximal arterioles. Comprehensive studies of the functional distribution of α1ARs and α2ARs in arteriolar networks (e.g. in mediating the actions of NA and its analogues in vivo) have focused on the cremaster muscle of male rats (Faber, 1988; McGillivray-Anderson & Faber, 1990; Anderson & Faber, 1991; Ohyanagi et al. 1991). In response to pharmacological manipulations and to sympathetic nerve stimulation, α1AR activation produced relatively greater constriction of the larger proximal (first-order, 1A) arterioles, than did α2AR activation. In contrast, α2AR activation caused greater constriction of the smaller distal (third-order, 3A) arterioles than did α1AR activation (Faber, 1988; Ohyanagi et al. 1991). In turn, differential responses between proximal and distal arteriolar branch orders to acidosis or to muscle contraction have been attributed to corresponding differences in the susceptibility of respective αAR subtypes to the actions of metabolic factors (McGillivray-Anderson & Faber, 1990; Anderson & Faber, 1991; Wray et al. 2004). Thus relative to α1AR-induced vasoconstriction, α2AR-induced vasoconstriction has been proposed to be more susceptible to functional inhibition. However, not all studies have shown greater selectivity for inhibiting α2AR- vs.α1AR-mediated vasoconstriction. For example, vasoconstrictor responses to agonists that were selective for respective αAR subtypes were attenuated to a similar extent during rhythmic handgrip exercise (Dinenno & Joyner, 2003; Rosenmeier et al. 2003).

A key functional difference between skeletal muscles and the cremaster muscle is that the former serve to stabilize and move the body while the latter has no skeletal attachments. Derived from musculature of the lower abdominal wall, the cremaster muscle supports the testes while regulating its temperature to maintain spermatogenesis. Thus, it is not clear whether the functional properties of αAR subtype distribution determined in the rat cremaster muscle can be accurately extrapolated to skeletal muscles that are integral to locomotion. In the gluteus maximus muscle (GM; a powerful hip extensor) of C57BL/6 mice, recent findings have shown that subtle activation of αARs (i.e. below that causing any change in diameter) can blunt arteriolar dilatation to brief tetanic contractions and restrict muscle blood flow at rest as well as during exercise (Jackson et al. 2010; Moore et al. 2010). However, as holds for other skeletal muscles, the functional distribution of αAR subtypes in the GM is unknown.

For the present study, our primary goal was to determine whether functional αAR subtypes vary with arteriolar branch order in a representative locomotor muscle of C57BL/6J mice. Using intravital microscopy to study arteriolar networks in the GM, we tested the hypothesis that the activation of α1ARs and α2ARs would produce similar effects across arteriolar branch orders. In contrast to blocking α1AR or α2AR subtypes during exposure to NA (Faber, 1988), our experimental design relied upon agonists and antagonists that we confirmed to be selective for each αAR subtype. This approach also avoided the possibility of non-selective inhibition of complementary receptors that might otherwise respond to NA. To test whether the variation in αAR subtype distribution within the microcirculation differed between tissues in the same species, additional experiments were performed to evaluate the functional distribution of α1ARs and α2ARs in arteriolar networks of the cremaster muscle.

In contrast to vasoconstriction evoked through αARs, the activation of vascular βARs produces vasodilatation as shown by isoproterenol addition to isolated arterioles in vitro (Aaker & Laughlin, 2002), intravenous infusion in anesthetized cats (Fronek & Zwiefach, 1975) or intra-arterial delivery to hindlimbs of exercising dogs (Buckwalter et al. 1997a). Remarkably, the effect of local βAR activation on intact arteriolar networks has received relatively little attention. Instead, to avoid possible actions of βAR activation, the functional distribution of αAR subtypes has typically been studied in the presence of propranolol (Faber, 1988; McGillivray-Anderson & Faber, 1990; Anderson & Faber, 1991; Ohyanagi et al. 1991) without ascertaining whether this inhibition of βARs affected responses to the activation of either αAR subtype. To provide new insight with respect to the functional consequences of βAR activation in intact arteriolar networks controlling blood flow to the mouse GM, we evaluated the responses of successive arteriolar branches to βAR activation and determined whether βAR inhibition affected arteriolar responses to the activation of αAR subtypes alone and in combination.

Methods

Animal care and use

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri and performed in accord with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The present experiments comply with the policies and regulations of The Journal of Physiology (Drummond, 2009). Male C57BL/6J mice (3–5 months; 25–30 g) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed at ∼22°C on a 12 h–12 h light–dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum for at least 1 week before being studied. At the end of the experimental procedures each day, the anaesthetized mouse was killed with an overdose of pentobarbital (intraperitoneal injection) followed by cervical dislocation.

Surgical preparation of GM and cremaster muscles

A mouse was anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (intraperitoneal injection, 60 mg kg−1) supplemented as needed (intraperitoneal injection, 20 mg kg−1) to prevent withdrawal from toe pinch. Hair was shaved from the hindquarters. Oesophageal temperature was maintained at 37–38°C by placing the mouse on an aluminum warming plate positioned on an acrylic platform. One muscle was studied per animal. Exposed muscles were superfused continuously (∼3 ml min−1) with a bicarbonate-buffered physiological salt solution (PSS; 34–35°C, pH 7.4) of the following composition (in mm): 131.9 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.17 MgSO4 and 18 NaHCO3 equilibrated with 5% CO2–95% N2.

Gluteus maximus muscle

The left GM was prepared as recently described (Jackson et al. 2010; Moore et al. 2010) by removing overlying skin and connective tissue, separating the muscle from the spine along its origin, and reflecting it away from the body while maintaining its insertion on the femur. The muscle was spread over a transparent pedestal (Sylgard 184; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) and pinned at the edges to approximate in situ dimensions.

Cremaster muscle

The left cremaster muscle was prepared by making a midline incision on the ventral surface of the scrotal sac, carefully separating the muscle from surrounding connective tissue, and then opening it along the ventral axis. An orchiectomy was performed and the cremaster muscle was spread over a transparent pedestal (Sylgard 184) and pinned at the edges to approximate in situ dimensions (Hungerford et al. 2000).

Intravital microscopy

The completed experimental preparation was transferred to the fixed stage (Burleigh Gibraltar; Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) of an intravital microscope (Nikon E600FN; Melville, NY, USA) and equilibrated for at least 30 min prior to beginning a protocol. The microscope was mounted on an X–Y translational platform (Burleigh Gibraltar) enabling it to be moved to different observation sites without disturbing the preparation. Images were acquired using a Nikon ×20 SLWD objective (numerical aperture, 0.35) using Köhler illumination from a long-working-distance condenser (numerical aperture, 0.52). Images were digitized with a charge-coupled device video camera (KP-D50; Hitachi Denshi; Japan) and observed on a digital monitor (ViewEra V191HV; Walnut, CA, USA) at a total magnification of ×1300. A video calliper calibrated to a stage micrometer (100 × 0.01 = 1 mm: Graticules Ltd, Tonbridge, Kent, UK) measured internal vessel diameter (spatial resolution ≤ 1 μm) as the widest distance between luminal edges. Output from the calliper was sampled at 40 Hz using a Powerlab/400 system (AD Instruments; Colorado Springs, CO, USA) coupled to a personal computer.

Vessel classification

To the extent possible, arterioles selected for study were standardized across preparations. Arteriolar networks bifurcating into successive branch orders were typically located in the Inferior region of the GM (see Fig. 1 of Moore et al. 2010). During the equilibration period, networks were scanned by eye and branch orders were classified as follows. First-order (1A): the most proximal branch embedded within striated muscle fibres, with the 1A origin defined as the site where its feed artery entered the muscle. Second-order (2A): originating as the first major bifurcation from the 1A. Third-order (3A): originating as the first major bifurcation from the 2A. For each branch order, the observation site was at least 150 μm downstream of its origin. Respective sites were observed individually within each network by shifting the field of view with reference to anatomical landmarks. One arteriolar network was studied per mouse.

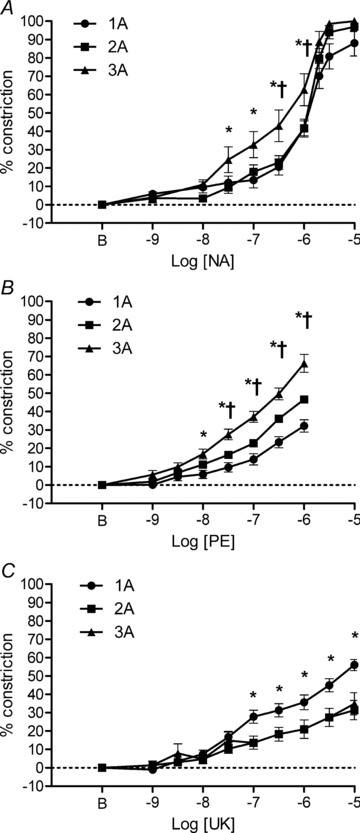

Figure 1. Arteriolar constriction with αAR activation in mouse GM.

A, non-selective activation of αARs with NA produced similar constrictions across arteriolar branch orders but 3A were more sensitive than 1A and 2A between 3 × 10−8 and 10−6m. *P < 0.05, 3A different from 1A. †P < 0.05, 3A different from 2A (n = 11 for 1A and 2A, n = 9 for 3A). B, selective activation of α1ARs with PE constricted 3A relatively more than 1A or 2A. *P < 0.01, 3A different from 1A. †P < 0.01, 3A different from 2A (n = 21 each). C, selective activation of α2ARs with UK 14304 (UK) constricted 1A relatively more than 2A or 3A. *P < 0.01, 1A significantly different from 2A and 3A (n = 20 each). B indicates resting baseline.

Criteria for inclusion

After the initial 30 min equilibration, arterioles were evaluated for sensitivity to oxygen as an index of the preparation's integrity by equilibrating the superfusion solution with 21% O2–5% CO2 (balance N2) for 5 min. Arterioles (2A and 3A) typically constricted by 5–10 μm during exposure to elevated O2. The superfusion solution was then re-equilibrated with 5% CO2–95% N2 for the remainder of the experimental protocol. At the end of experiments, the maximum diameter of each observation site was determined during superfusion with 10−4m sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Only preparations in which arterioles exhibited spontaneous vasomotor tone, constricted to elevated oxygen, and dilated vigorously to SNP were included in the study. More than 90% of muscle preparations studied during the present experiments satisfied these criteria.

Administration of agonists and antagonists

Adrenoreceptor agonists and antagonists were prepared fresh on the morning of an experiment, administered topically via addition to the superfusion solution and expressed as final concentrations over the tissue. The superfusion solution was delivered by gravity feed onto the preparation from a 60 ml chamber consisting of a vertically mounted syringe secured within an aluminum heater block (SW-60, Warner Instruments; Hamden, CT, USA). Chamber volume was maintained by gravity feed from a 500 ml reservoir. For cumulative concentration–response experiments to AR agonists, inflow from the reservoir was shut to fix the volume of solution within the chamber. The appropriate volume of stock concentration of agonist or antagonist was added to achieve the desired final concentration; continuous bubbling of gas within the chamber ensured rapid mixing. Stock solutions were prepared at concentrations ensuring that the volume added was always less than 1% of the chamber volume. Arteriolar diameters at each observation site were recorded for a given condition and then inflow from the reservoir was restored. Once the original volume in the chamber was attained, inflow from the reservoir was again shut and the next concentration of the agonist was administered. This procedure was repeated throughout concentration–response determinations. For treatment with antagonists, the desired concentration was prepared in the 500 ml reservoir supplying the 60 ml superfusion chamber to which agonists were added. When different antagonists were used for a given experiment, each was prepared in its own 500 ml reservoir. Drugs and chemicals and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Experimental protocols

The primary goal of these experiments was to determine the functional distribution of α1ARs, α2ARs and βARs in 1A, 2A and 3A of the mouse GM.

Protocol 1: functional distribution of arteriolar αARs in the GM

We first evaluated the stability of AR activation in GM arterioles over the time course of a typical experiment (∼3 h). One group of mice was used to evaluate the non-selective αAR agonist NA. Another group of mice was used to evaluate the α1AR-selective agonist phenylephrine (PE) and a third group to evaluate the α2AR-selective agonist UK 14304. Each agonist was studied in half-log increments (10−9m to 10−5m unless stated otherwise) by evaluating arteriolar diameters to cumulative increases in concentration. Each concentration of agonist was equilibrated for 3 min or until vessel diameters had reached stable values and the internal diameters of 1A, 2A and 3A were recorded (in random order). After the final agonist concentration was evaluated, superfusion with control PSS was restored for ∼10 min while arterioles recovered to their initial (post 30 min equilibration) baseline diameters. This entire procedure was repeated 4 times for each agonist. One agonist was studied in each GM preparation.

Protocol 2: functional distribution of arteriolar βARs in the GM

While activating βARs promotes vasodilatation, little is known of how βAR activation affects arteriolar diameters in vivo (Fronek & Zweifach, 1975) and few investigators have determined whether concomitant inhibition of βARs affects arteriolar responses to αAR activation (Marshall, 1982). Therefore, the functional distribution of βAR in arterioles of the GM was assessed by evaluating 1A, 2A and 3A diameters during cumulative addition of the βAR agonist isoproterenol (10−11m to 10−5m). In one group of mice, responses to isoproterenol were re-evaluated after equilibrating with propranolol (10−7m) for at least 15 min. In three additional groups, we determined whether βAR inhibition with propranolol affected constrictions to NA, PE or UK 14304. During propranolol treatment, one αAR agonist was evaluated in each GM preparation.

Protocol 3: selectivity of αAR agonists and antagonists

To investigate the selectivity of functional αAR subtypes in arterioles of the mouse GM, we evaluated the effect of αAR antagonists on responses to selective αAR agonists. Antagonists were equilibrated for ∼15 min before testing for their actions. One agonist was evaluated in the presence of respective antagonists in each GM preparation as follows.

Protocol 3A: effect of αAR subtype antagonists on arteriolar responses to α1AR activation .

Responses to PE were first evaluated under control conditions. The agonist was removed and the preparation was superfused with control PSS for ∼10 min. Responses to PE were next re-evaluated in the presence of rauwolscine (10−7m; α2AR antagonist), which was then removed and the preparation superfused with control PSS for ∼10 min. Responses to PE were evaluated a final time in the presence of prazosin (10−8m, α1AR antagonist).

Protocol 3B: effect of αAR subtype antagonists on arteriolar responses to α2AR activation .

Responses to UK 14304 were first evaluated under control conditions. The agonist was removed and the preparation was superfused with control PSS for ∼10 min. Responses to UK 14304 were then re-evaluated in the presence of prazosin (10−8m), which was subsequently removed and the preparation superfused with control PSS for ∼10 min. Responses to UK 14304 were evaluated a final time in the presence of rauwolscine (10−7m).

Protocol 4: tissue specificity of αAR subtype distribution in arteriolar networks

Experiments were performed in the cremaster muscle of additional mice to determine whether functional αAR subtype distribution of 1A, 2A and 3A varied between muscles. Diameter responses to cumulative increases in [NA] were evaluated first. Following washout and recovery, responses to cumulative increases in [PE] or [UK 14304] were evaluated (order randomized across experiments). Following further washout and recovery, responses to the third agonist were evaluated.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

Data are presented as the diameter change (in μm) from resting baseline = [(Drest−Dtreatment)], as percentage constriction = [(Drest−Dtreatment)/Drest] (where 100% corresponds to lumen closure), or as percentage maximal dilatation = [(Dtreatment−Drest)/(Dmax−Drest)]. The diameter following the initial 30 min equilibration was taken as Drest. The diameter recorded at a given agonist concentration was designated Dtreatment. The diameter recorded in the presence of 10−4m SNP was designated Dmax.

Data were analysed using one- and two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (Prism 5, GraphPad Software; La Jolla, CA, USA). When significant F-ratios were obtained, post hoc comparisons were made using Bonferroni or Tukey tests. Summary data are expressed as mean ±s.e. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 69 mice were used in the present experiments. Resting and maximal diameters of 1A, 2A and 3A for the GM and cremaster muscles studied are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Arteriolar diameters in mouse gluteus maximus and cremaster muscles

| Branch order | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 2A | 3A | |

| Gluteus maximus | |||

| Resting (μm) | 31 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 |

| Maximal (μm) | 50 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 |

| Cremaster | |||

| Resting (μm) | 39 ± 1 | 22 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 |

| Maximal (μm) | 57 ± 4 | 39 ± 4 | 24 ± 3 |

Summary values (means ±s.e.) for internal diameters of arterioles in vivo. For each arteriolar branch order, resting values were recorded after the 30 min equilibration period following surgical preparation. Maximal values recorded at the end of experiments in the presence of 10−4m SNP. Data for GM arterioles are from 60 mice. Data for cremaster muscle arterioles are from 9 mice.

Protocol 1: functional distribution of αARs in the GM

A comparison of relative responses to selective and non-selective αAR subtype activation is presented in Fig. 1. The concentration–response relationships to respective agonists were stable over time (see Figs. 1–3 in Supplemental material, available online only). Therefore, data from the four repeated determinations were averaged for each mouse. In response to NA (Fig. 1A), respective branch orders had similar percentage maximal peak constrictions (1A = 88 ± 7%, 2A = 97 ± 3%, 3A = 100 ± 0%). However, 3A exhibited greater (P < 0.05) responses than 1A or 2A between 3 × 10−8m and 10−6m. Respective log EC50 values were not significantly different (1A: −5.9 ± 0.1; 2A: −5.9 ± 0.1; 3A: –6.1 ± 0.3). In response to PE (Fig. 1B), peak constrictions of 3A (66 ± 5% of maximal) were greater (P < 0.05) than those of 1A (32 ± 3%) or 2A (47 ± 2%). However, the actual changes in diameter were similar across branch orders (see Fig. 3B). In response to UK 14304 (Fig. 1C), constrictions were greater (P < 0.05) for 1A (56 ± 3%) compared to 2A (31 ± 5%) or 3A (35 ± 6%). This pattern of response indicates greater functional activity of α1ARs in 3A and of α2ARs in 1A.

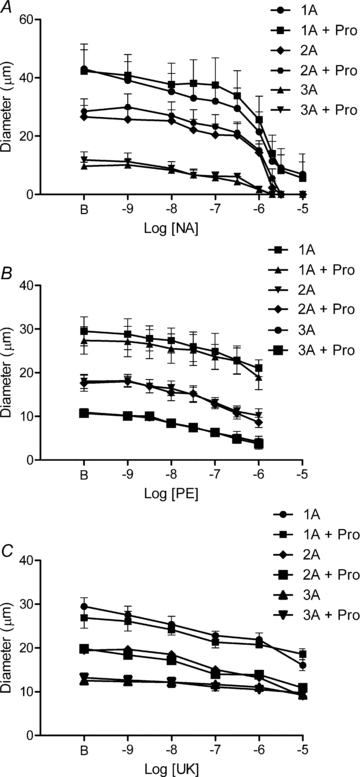

Figure 3. Inhibition of βARs does not alter responses to αAR agonists.

Addition of propranolol (Pro, 10−7m) had no significant effect on arteriolar constrictions to NA (A, n = 4), PE (B, n = 5), or UK 14304 (UK) (C, n = 5). B indicates resting baseline.

Because constrictions to PE or UK 14304 did not reach an apparent plateau, EC50 values could not be determined for these agonists. In preliminary studies, exposure to PE at a concentration >10−6m was found to disrupt reproducible responses to consecutive concentration–response experiments, thereby establishing 10−6m as the upper limit for PE concentration in these experiments.

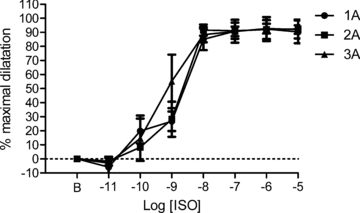

Protocol 2: functional distribution of βARs in the GM

Each arteriolar branch order dilated in response to βAR activation with isoproterenol (Fig. 2). Peak absolute changes in diameter for 1A, 2A and 3A were not significantly different (18 ± 4 μm, 18 ± 3 μm and 17 ± 2 μm, respectively). Despite differences in resting and maximal diameters between arteriolar branch orders (Table 1), when responses to isoproterenol were expressed relative to respective maximal dilatations (i.e. diameter changes) obtained with SNP (Table 1), there were no significant differences in efficacy or sensitivity. This similarity in behaviour was reflected in respective log EC50 values (1A: −8.7 ± 0.2; 2A: −8.8 ± 0.2; 3A: −9.2 ± 0.2). In the presence of propranolol (10−7m), responses to isoproterenol were shifted to the right by nearly 2 log-orders (P < 0.01), confirming its effectiveness as an inhibitor of βARs (Supplemental Fig. 4). The inhibition of βARs had no effect on constrictions to NA, PE, or UK 14304 in 1A, 2A or 3A (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Arteriolar dilatation with βAR activation in mouse GM.

Isoproterenol (ISO) dilated 1A, 2A and 3A to 90 ± 8%, 92 ± 7% and 92 ± 3% of the maximal dilatation (diameter change in μm) obtained with 10−4m SNP (see Table 1). There were no significant differences between arteriolar branch orders (n = 6 arterioles for each branch order). B indicates resting baseline.

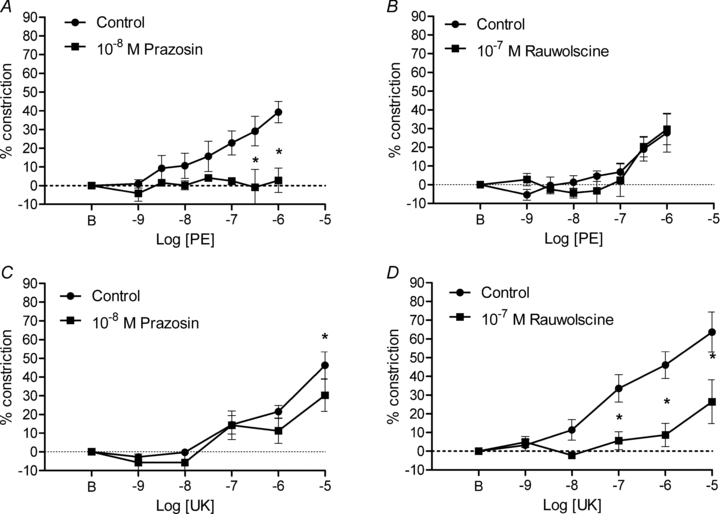

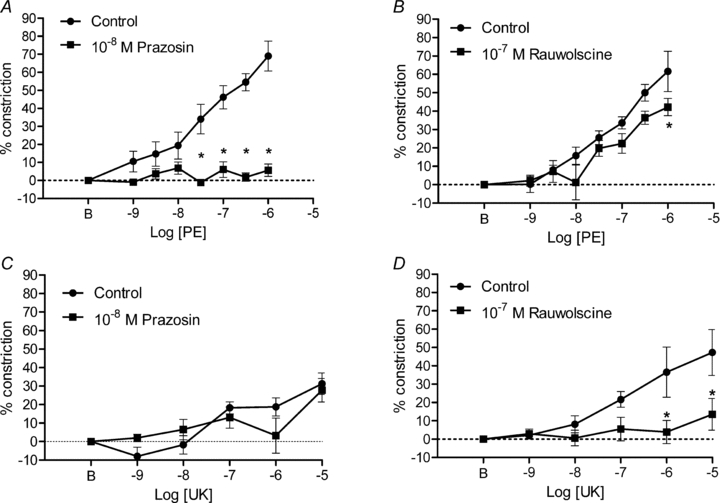

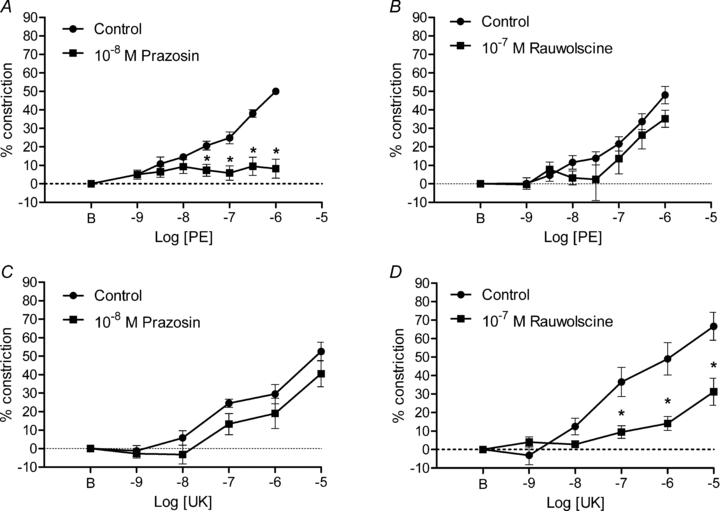

Protocol 3: selectivity of αAR agonists and antagonists

Results from these experiments are presented for 1A, 2A and 3A in Figs. 4–6, respectively, and confirm the selectivity of our pharmacological treatments. In response to PE, constriction of 1A was inhibited by 10−8m prazosin (Fig. 4A) but was unaltered by 10−7m rauwolscine (Fig. 4B). In response to UK 14304, 1A constriction was effectively maintained (except for an attenuated response at 10−5m) in the presence of prazosin (Fig. 4C) but was inhibited by rauwolscine (Fig. 4D). For 2A, constriction in response to PE was inhibited by prazosin (Fig. 5A) but was unaffected by rauwolscine (Fig. 5B). In response to UK 14304, 2A constriction was maintained in the presence of prazosin (Fig. 5C) but was inhibited by rauwolscine (Fig. 5D). For 3A, constriction in response to PE was inhibited by prazosin (Fig. 6A) but maintained in the presence of rauwolscine (except for an attenuated response at 10−6m) (Fig. 6B). In response to UK 14304, the modest level of 3A constriction was preserved in the presence of prazosin (Fig. 6C) but was inhibited by rauwolscine (Fig. 6D). Collectively, these data support the use of prazosin (10−8m) and rauwolscine (10−7m) as selective antagonists of α1ARs and α2ARs, respectively, in arterioles of the mouse GM.

Figure 4. Activation and inhibition of α1ARs and α2ARs in 1A of mouse GM.

A, the α1AR agonist PE progressively increased vasoconstriction that was inhibited by prazosin (n = 6). B, rauwolscine had no significant affect on constrictions to PE (n = 5). C, with the exception of an attenuated response at 10−5m UK 14304 (UK), prazosin did not affect constrictions to α2AR activation (n = 5). D, constrictions to UK 14304 were inhibited by rauwolscine (n = 6). *P < 0.01 in A; P < 0.05 in C and D. B indicates resting baseline.

Figure 6. Activation and inhibition of α1ARs and α2ARs in 3A of mouse GM.

A, the α1AR agonist PE progressively increased vasoconstriction that was inhibited by prazosin (n = 6). B, with the exception of an attenuated response at 10−6m, responses to PE were preserved in the presence of rauwolscine (n = 5). C, constrictions to the α2AR agonist UK 14304 (UK) were preserved in the presence of prazosin (n = 5). D, constrictions to UK 14304 were inhibited by rauwolscine (n = 6). One 3A in this group constricted to closure which elevated the mean response. In all other mice, peak constriction of 3A was typically <30% in response to UK 14304 (see Fig. 1C). *P < 0.01 in A; P < 0.05 in B and D. B indicates resting baseline.

Figure 5. Activation and inhibition of α1ARs and α2ARs in 2A of mouse GM.

A, the α1AR agonist PE progressively increased vasoconstriction that was inhibited by prazosin (n = 6). B, constrictions to PE were preserved in the presence of rauwolscine (n = 5). C, constrictions to the α2AR agonist UK 14304 (UK) were preserved in the presence of prazosin (n = 5). D, constrictions to UK 14304 were inhibited by rauwolscine (n = 6). *P < 0.01 in A; P < 0.05 in D. B indicates resting baseline.

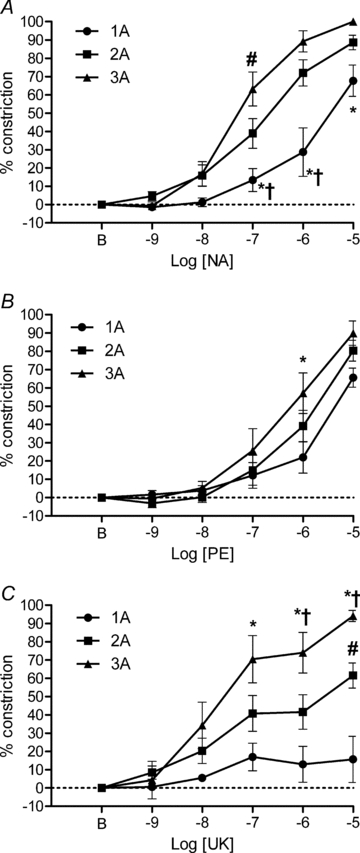

Protocol 4: tissue specificity of αAR subtype distribution in arteriolar networks

Because our results for the mouse GM indicated a different pattern of functional αAR subtype distribution in respective arteriolar branch orders than reported for the rat cremaster muscle (Faber, 1988), we investigated responses to NA, PE and UK 14304 in arterioles of the cremaster muscle in mice identical to those in which the GM was studied (Fig. 7). For 1A, constrictions to NA were consistently less (P < 0.05) than those of 2A or 3A (Fig. 7A). Constrictions to PE appeared to be greatest in 3A, which were significantly different from responses of 1A and 2A (P < 0.05) at 10−6m (Fig. 7B). For UK 14304, 2A and 3A constricted progressively as agonist concentration increased with 3A exhibiting greater (P < 0.05) responses than 2A (Fig. 7C). In contrast, 1A showed little response to UK 14304. This pattern of arteriolar reactivity in the mouse cremaster muscle indicates greater functional activity of α1ARs in 1A and of α2ARs in 3A when compared to respective arteriolar branch orders in the GM. However this pattern is consistent with that observed for α1AR and α2AR subtype distribution first reported for the rat cremaster muscle (Faber, 1988).

Figure 7. Arteriolar constriction to αAR activation in mouse cremaster muscle.

A, non-selective activation of αARs with NA produced variable levels of percentage maximal constriction across arteriolar branch orders with 3A more sensitive than 2A at 10−7m and 1A less sensitive than 2A or 3A between 10−7 and 10−5m. *P < 0.05, 1A different from 3A. #P < 0.05, 2A different from 3A. †P < 0.05, 2A different from 1A. B, selective activation of α1ARs with PE produced similar percentage maximal constriction across arteriolar branch orders but 3A were more sensitive than 1A at 10−6m. *P < 0.05, 3A different from 1A. C, selective activation of α2ARs with UK 14304 (UK) constricted 3A relatively more than 1A or 2A. *P < 0.05, 3A different from 1A. #P < 0.05, 2A different than 1A. †P < 0.05, 3A different from 2A. n = 9 in all panels. B indicates resting baseline.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the functional distribution of α1ARs and α2ARs in multiple arteriolar branch orders of a locomotor muscle in the mouse. We demonstrate that functional αAR subtype distribution in arterioles controlling blood flow to the GM varies between branch orders. Our data illustrate that α2AR reactivity is most prominent in proximal (1A) arterioles while α1AR reactivity is most prominent in distal (3A) arterioles. We therefore reject the hypothesis that functional αAR subtype distribution is uniform across arteriolar branch orders in the mouse GM. Moreover, the pattern of functional αAR subtype distribution shown here in the mouse GM contrasts with that reported for the rat cremaster muscle, where α1AR reactivity predominates in 1A and α2AR reactivity predominates in 3A. Remarkably, our findings in the mouse cremaster muscle are consistent with those in the rat cremaster muscle. In turn, we conclude that results from the cremaster muscle cannot be extrapolated to a locomotor muscle such as the GM or – by inference – to other locomotor skeletal muscles. The present findings illustrate the importance of determining the pattern of αAR subtype distribution in the muscle being studied for adrenergic reactivity to experimental treatments. Whereas responses to combined or selective αAR subtype activation were unaffected by βAR blockade, the functional distribution of βARs in GM arterioles appears uniform across branch orders. Indeed, signalling events initiated by βARs produced dilatations of respective arteriolar branch orders that were not different from dilatations obtained with the NO donor, SNP. We thereby demonstrate the efficacy of βAR-mediated dilatation throughout arteriolar networks controlling blood flow to skeletal muscle in vivo.

Experimental activation of αARs

In the peripheral vasculature, sympathetic nerves release neurotransmitters which act on post-junctional αARs to initiate vasoconstriction (Vanhoutte et al. 1981). Experimentally, several methods have been employed to produce this response including electrical stimulation and the administration of αAR agonists. Perivascular sympathetic nerve activation can be accomplished by stimulating the paravertebral sympathetic chain (Hilton et al. 1970; Fleming et al. 1987; Boegehold & Johnson, 1988; Ohyanagi et al. 1991; Dodd & Johnson, 1993; Thomas et al. 2001) or through electrodes positioned on the feed artery supplying the muscle (Marshall, 1982; VanTeeffelen & Segal, 2003; Haug & Segal, 2005). However, pre-junctional inhibition of neurotransmitter release or co-release of other substances (e.g. adenosine triphosphate and neuropeptide Y) may affect the pattern of post-junctional AR activation and vasoreactivity (Vanhoutte et al. 1981). In the present study, we were concerned with post-junctional AR distribution on arterioles and sought to avoid possible confounding mechanisms associated with nerve activation (Dodd & Johnson, 1993). Adrenergic agonists are effective whether administered through intravascular injection (Remensnyder et al. 1962; Hilton et al. 1970; Fronek & Zweifach, 1975; Dodd & Johnson, 1993; Buckwalter et al. 1997a) or applied topically in the superfusion solution (Faber, 1988; Haug & Segal, 2005; Jackson et al. 2010). We used the latter approach for the present experiments to minimize possible systemic effects of intravascular delivery (Dodd & Johnson, 1993). Our time controls based upon repeated concentration–response experiments confirmed that αAR sensitivity and efficacy were well maintained over time (Supplemental Figs. 1–3). Furthermore, in contrast to earlier studies using nerve stimulation (Marshall, 1982; Boegehold & Johnson, 1988; Dodd & Johnson, 1993; VanTeeffelen & Segal, 2003), arterioles observed here did not undergo ‘escape’. This difference may be attributable to constant exposure to the agonist in the superfusion solution instead of sympathetic nerve stimulation that can invoke prejunctional inhibition of neurotransmitter release (Vanhoutte et al. 1981; Dodd & Johnson, 1993).

Effects of combined αAR subtype activation

Because individual vessels within a resistance network may have differential sensitivities to NA (Marshall, 1982), it was of interest to ascertain the effects of combined αAR subtype activation across arteriolar branch orders within the mouse GM. We found that cumulative addition of NA to the superfusion solution produced robust constriction of 1A, 2A and 3A (Figs 1A and 3A). Moreover, each branch order had similar maximum responses and log EC50 values (Fig. 1). This behaviour contrasts with our findings in the mouse cremaster muscle (Fig. 7A) and with earlier studies of the rat spinotrapezius muscle (Marshall, 1982), where distal arterioles appeared to have greater sensitivity to NA. In addition, all branch orders in the GM underwent nearly complete closure at the highest concentrations of NA (Figs. 1A and 3A), which was not the case for 1A in the cremaster (Fig. 7A). The large and consistent arteriolar constrictions evoked by NA illustrated that respective branch orders within the GM are highly sensitive to αAR activation and that NA produces similar relative responses across branch orders when α1ARs and α2ARs are stimulated simultaneously.

Effects of selective αAR subtype activation

Concentration–response experiments to NA established that αAR were functionally expressed in 1A, 2A and 3A of the GM (Fig. 1A). However, our goal was to determine the profile of functional αAR subtypes in respective arteriolar branch orders. Remarkably, selective activation of α1ARs and α2ARs resulted in different response characteristics in 1A, 2A and 3A (Fig. 1). The α1AR agonist PE evoked similar absolute diameter changes in respective branches (Fig. 3B). When these data were normalized to account for respective differences in arteriolar diameter, constrictions were significantly different with 3A > 2A > 1A (Fig. 1B). It therefore appears that functional α1AR are distributed unevenly between arteriolar branch orders, with 3A being the most responsive to PE. In turn, α2AR stimulation with UK 14304 evoked constrictions in 1A that were greater than those evoked in 2A or 3A (Figs. 1C and 3C). Observing that 3A constricted to closure in response to NA and nearly to closure with PE but not to UK 14304 (Fig. 3) supports the contention that α2ARs are distributed heterogeneously among arteriolar branch orders of the mouse GM. Furthermore, neither α1AR nor α2AR activation alone are as effective as combined α1AR +α2AR activation in constricting arterioles in this muscle. By inference, responses to respective selective agonists (Fig. 1B and C) provide an index of the contribution of respective αAR subtypes during their combined response to NA (Fig. 1A).

Effects of selective αAR subtype antagonists on selective αAR subtype activation

Effective use of αAR antagonists has been a powerful tool in resolving which AR subtype mediates specific physiological responses (Vanhoutte et al. 1981; Timmermans et al. 1987; Faber, 1988; Haug & Segal, 2005). In the mouse GM, it was unknown whether blockade of one αAR subtype would increase or decrease the sensitivity of arterioles to the remaining αAR subtype. To address this concern, we performed comprehensive control experiments to directly test the selectivity of αAR subtype antagonists as used in the present study. The α1AR antagonist prazosin (10−8m) inhibited responses to the α1AR agonist PE (Figs 4A, 5A and 6A) and this effect was most pronounced in 3A (Fig. 6A), where responses to AR stimulation were mediated primarily through α1ARs (Fig. 1). Although prazosin reduced maximal constriction to UK 14304 in 1A slightly (Fig. 4C), it had no other significant effects on responses to this α2AR agonist (Figs. 4C, 5C and 6C). The α2AR antagonist rauwolscine (10−7m) produced the largest inhibition to UK 14304 in 1A where the potency of this α2AR agonist was greatest (Figs. 1C and 4D). Rauwolscine also inhibited responses to UK 14304 in 2A and in 3A where responses to this α2AR agonist were depressed relative to 1A responses (Fig. 1C). We conclude that, as used in the present study, prazosin and rauwolscine were selective inhibitors of respective αAR subtypes of the mouse GM.

Neither prazosin nor rauwolscine had significant effects on resting arteriolar diameters (data not shown). Thus if there were constitutive activation of αAR for arterioles in the GM at rest, it was at a level below that required to enhance spontaneous vasomotor tone. This conclusion is consistent with recent findings in the GM, where the non-selective AR antagonist, phentolamine (10−6m), also had no effect on resting arteriolar diameter (Jackson et al. 2010; Moore et al. 2010). It should be recognized that as a barbiturate anaesthetic, pentobarbital inhibits sympathetic nerve activity. Such actions may explain the lack of effect of αAR antagonists on resting tone. In contrast, findings in conscious humans (Dinenno et al. 2001) and animals (Buckwalter et al. 1997b; O’Leary et al. 1997) have shown that the inhibition of αARs with phentolamine or prazosin enhance limb blood flow at rest and during exercise. Nevertheless, constitutive activity of αARs is present in the GM preparation of anaesthetized mice as recently illustrated: despite no effect on resting diameter, phentolamine (10−6m) enhanced the magnitude of rapid onset vasodilatation in ‘Old’ (20 month) male mice (Jackson et al. 2010) and promoted spreading dilatation along arterioles in ‘Young’ (3 month) male mice not different from those studied here (Moore et al. 2010). Through direct observations of the microcirculation, the GM preparation is affording new insight into such subtle physiological consequences of adrenergic signalling in the regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow and these actions may well be enhanced in the absence of anaesthesia.

Regional differences in the functional distribution of αAR subtypes

The most comprehensive examination of functional αAR distribution in the microcirculation of skeletal muscle has come from studies in the rat cremaster muscle (Faber, 1988; McGillivray-Anderson & Faber, 1990; Anderson & Faber, 1991; Ohyanagi et al. 1991). Findings from these experiments indicated that functional α1AR predominate in 1A while functional α2AR predominate in 3A. Because our observations in the mouse GM indicated a reciprocal pattern of αAR subtype expression, we tested whether such properties were inherent to the GM, or whether they were manifest in other vascular beds of the mouse. As shown in the mouse cremaster muscle (Fig. 7), PE produced robust constriction of each arteriolar branch order. In contrast to the GM (Fig. 1C), UK 14304 evoked the greatest constrictions of cremasteric 3A, with little effect on the diameter of 1A (Fig. 7C). Our data from arterioles of the mouse cremaster muscle are therefore consistent with the αAR subtype distribution described for arterioles of the rat cremaster muscle (Faber, 1988; McGillivray-Anderson & Faber, 1990; Anderson & Faber, 1991; Ohyanagi et al. 1991).

The present findings collectively indicate that αAR subtype distribution in arteriolar networks varies between the GM and the cremaster muscle of the mouse. Studies of the rat cremaster muscle have concluded that the preponderance of α2ARs on 3A contributes to the ability of these vessels to escape from sympathetic vasoconstriction (McGillivray-Anderson & Faber, 1990; Anderson & Faber, 1991). However, our finding that functional α1ARs predominate over α2ARs in 3A of the GM (Fig. 1B and C) contrasts with such inferences. In turn we suggest that the greater ability of distal arterioles to dilate during sympathetic nerve activity in other preparations of skeletal muscle (Folkow et al. 1971; Marshall, 1982; VanTeeffelen & Segal, 2003) may occur irrespective of αAR subtype distribution. Although adrenergic sensitivity has been shown to vary between resistance vessels of different skeletal muscles (Hilton et al. 1970; Gray, 1971; Laughlin & Armstrong, 1987), it does not appear related to corresponding differences in muscle fibre type (Aaker & Laughlin, 2002; Lambert & Thomas, 2005). As shown for cutaneous arterioles in the guinea-pig ear, regional variability in sensitivity to αAR subtype-selective agonists may be associated with the proportion of sympathetic axons containing the co-transmitter neuropeptide Y (Morris, 1994). In turn, differences between muscles in vascular sensitivity to NA or to sympathetic nerve activity may reflect corresponding differences in the density of terminal sympathetic innervation (Hilton et al. 1970). Nevertheless, we conclude that findings based upon the pattern of functional αAR subtype distribution in arterioles of the cremaster muscle need not apply to skeletal muscles involved in locomotion. Nor should results shown here for the GM be generalized to other skeletal muscles without appropriate controls.

Activation and inhibition of βARs

Vasodilatation in response to βAR activation with isoproterenol has been demonstrated in arterioles isolated from rat skeletal muscles (Aaker & Laughlin, 2002), arterioles controlling blood flow in the tenuissimus muscle of anesthetized cats (Fronek & Zweifach, 1975) and to hindlimbs of exercising dogs (Buckwalter et al. 1997a). In previous studies, propranolol was used proactively to block βARs without evaluating their role in responses to adrenergic agonists (Medgett & Langer, 1984; Flavahan et al. 1987; Faber, 1988; McGillivray-Anderson & Faber, 1990; Anderson & Faber, 1991; Ohyanagi et al. 1991). Here we illustrate that isoproterenol is capable of eliciting near-maximal dilatation across arteriolar branch orders of the mouse GM with similar efficacy and potency (Fig. 2). Given such capacity to relax vascular smooth muscle, we questioned whether constitutive activation of βARs may influence constrictor responses to αAR activation. Propranolol was found to have no effect on resting diameters (data not shown) thus constitutive βAR activity was not apparent during our experiments. Selective inhibition of βARs with propranolol was demonstrated by the shift in responses to isoproterenol by ∼2 log orders in concentration (Supplemental Fig. 4) while having no effect on constrictions to NA, PE, or UK 14304 (Fig. 3). Our findings thereby confirm earlier studies illustrating that βARs were not stimulated during activation of αARs (Marshall, 1982; Morris, 1994). Given such pronounced arteriolar dilatations in response to pharmacological activation of βARs (Fig. 2), the contribution of these receptors in regulating peripheral resistance remains to be ascertained. In contrast, the role of βARs on skeletal muscle fibres in promoting glycogenolysis has been well defined (Dietz et al. 1980). As shown in rats (Martin et al. 1989b) and humans (Martin et al. 1989a) the density of βARs was several-fold greater for slow-twitch oxidative (Type I) muscle fibres compared to fast-twitch glycolytic (Type II) muscle fibres. However, βARs had higher affinity in the Type II fibres (Martin et al. 1989b). While the density of βARs on arterioles was similar between muscles, arterioles were more numerous in the soleus (Type I) compared to the gastrocnemius (Type II) muscle (Martin et al. 1989b), consistent with greater oxidative capacity of the soleus muscle.

Summary and conclusions

The location of AR subtypes and the control they exert over the resistance vasculature is integral to sympathetic control of muscle blood flow concomitant with the regulation of blood pressure, particularly during muscular exercise. The present study provides evidence that αAR subtypes are not uniformly distributed in arteriolar networks of the mouse GM. Third-order arterioles exhibited relatively greater responses to PE than UK 14304, indicating that functional α1AR activation is able to evoke relatively greater constriction in distal arterioles when compared to that evoked by α2ARs. In contrast, 1A in the GM exhibited relatively greater responses to UK 14304 than to PE, indicating that α2AR activation is able to evoke relatively greater constriction in proximal arterioles of this muscle. Prazosin (10−8m) effectively inhibited α1ARs while preserving α2AR responses. Rauwolscine (10−7m) effectively inhibited α2ARs while preserving α1AR responses. This pattern of functional αAR subtype distribution in arterioles of the GM differed from that found in the mouse cremaster muscle (or first reported in the rat cremaster muscle; Faber, 1988), where α1ARs predominate in 1A while α2ARs predominate in 3A. The functional distribution of βARs appears to be uniform across arteriolar branch orders of the GM as 1A, 2A and 3A responded similarly to isoproterenol with near-maximal dilatations. Vasoconstriction to αAR activation was not affected by βAR inhibition as propranolol had no effect on arteriolar responses to NA, PE or UK 14304, while clearly inhibiting responses to isoproterenol. The consistency observed among our results obtained with agonists and antagonists targeted to AR subtypes confirms the selectivity of our pharmacological interventions.

Distal branches of the resistance network have long been recognized to more readily ‘escape’ from sympathetic vasoconstriction (Folkow et al. 1971; Mellander, 1971; Marshall, 1982). Comprehensive studies in the rat cremaster muscle have associated such behaviour with the prevalence of α2ARs on distal arterioles, in contrast to the prevalence of α1ARs on proximal arterioles. Our present findings in the mouse cremaster muscle support these original studies. Nevertheless, our present findings in the mouse GM illustrate that this reasoning need not apply to other skeletal muscles. Implicit to this interpretation is that properties other than αAR subtype contribute to the ability of distal arterioles to oppose sympathetic vasoconstriction. The interaction between sympathetic neuroeffector signalling and metabolic demand in skeletal muscle should account for the functional distribution of αAR subtypes in the muscle of interest. Insight gained from the present experiments provides a foundation for the mouse GM as a model for investigating signalling events mediated through α1ARs vs.α2ARs which contribute to the adrenergic restriction of muscle blood flow with ageing (Proctor & Joyner, 1997; Dinenno et al. 2001; Jackson et al. 2010).

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by Grant RO1-HL086483 from the Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, United States Public Health Service. A. W. Moore was supported by a Life Sciences Fellowship from the University of Missouri.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ARs

adrenoreceptors

- GM

gluteus maximus muscle

- NA

noradrenaline

- PE

phenylephrine

- PSS

physiological saline solution

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- 1A

first-order arterioles

- 2A

second-order arterioles

- 3A

third-order arterioles

Author contributions

A.W.M., W.F.J. and S.S.S. contributed to the conception, experimental design, analysis and interpretation of the experiments contained in this study. A.W.M. performed all of the experiments in the laboratory of S.S.S. at the University of Missouri and prepared the first draft of this article which was edited by W.F.J. and S.S.S. All co-authors have approved the version submitted to be considered for publication.

Author's present address

A.W. Moore: Westmont College, Department of Biology, 955 La Paz Road, Santa Barbara, CA 93108, USA.

References

- Aaker A, Laughlin MH. Diaphragm arterioles are less responsive to α1-adrenergic constriction than gastrocnemius arterioles. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1808–1816. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01152.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KM, Faber JE. Differential sensitivity of arteriolar α1 and α2 adrenoceptor constriction to metabolic inhibition during rat skeletal muscle contraction. Circ Res. 1991;69:174–184. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boegehold MA, Johnson PC. Response of arteriolar network of skeletal muscle to sympathetic nerve stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1988;254:H919–H928. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.5.H919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter JB, Mueller PJ, Clifford PS. Autonomic control of skeletal muscle vasodilation during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1997a;83:2037–2042. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter JB, Mueller PJ, Clifford PS. Sympathetic vasoconstriction in active skeletal muscles during dynamic exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1997b;83:1575–1580. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.5.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz MR, Chiasson JL, Soderling TR, Exton JH. Epinephrine regulation of skeletal muscle glycogen metabolism. Studies utilizing the perfused rat hindlimb preparation. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:2301–2307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinenno FA, Joyner MJ. Blunted sympathetic vasoconstriction in contracting skeletal muscle of healthy humans: is nitric oxide obligatory? J Physiol. 2003;553:281–292. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinenno FA, Tanaka H, Stauffer BL, Seals DR. Reductions in basal limb blood flow and vascular conductance with human ageing: role for augmented α-adrenergic vasoconstriction. J Physiol. 2001;536:977–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd LR, Johnson PC. Antagonism of vasoconstriction by muscle contraction differs with α-adrenergic subtype. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1993;264:H892–H900. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.3.H892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber JE. In situ analysis of α-adrenoceptors on arteriolar and venular smooth muscle in rat skeletal muscle microcirculation. Circ Res. 1988;62:37–50. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavahan NA, Cooke JP, Shepherd JT, Vanhoutte PM. Human postjunctional Alpha-1 and Alpha-2 adrenoceptors: differential distribution in arteries of the limbs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;241:361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming BP, Barron KW, Howes TW, Smith JK. Response of the microcirculation in rat cremaster muscle to peripheral and central sympathetic stimulation. Circ Res. 1987;61:II26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkow B, Sonnenschein RR, Wright DL. Loci of neurogenic and metabolic effects on precapillary vessels of skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1971;81:459–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1971.tb04924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronek K, Zweifach BW. Microvascular pressure distribution in skeletal muscle and the effect of vasodilation. Am J Physiol. 1975;228:791–796. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.228.3.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SD. Responsiveness of the terminal vascular bed in fast and slow skeletal muscles to α-adrenergic stimulation. Angiologica. 1971;8:285–296. doi: 10.1159/000157902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug SJ, Segal SS. Sympathetic neural inhibition of conducted vasodilatation along hamster feed arteries: complementary effects of α1- and α2-adrenoreceptor activation. J Physiol. 2005;563:541–555. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton SM, Jeffries MG, Vrbova G. Functional specializations of the vascular bed of soleus. J Physiol. 1970;206:543–562. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford JE, Sessa WC, Segal SS. Vasomotor control in arterioles of the mouse cremaster muscle. FASEB J. 2000;14:197–207. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DN, Moore AW, Segal SS. Blunting of rapid onset vasodilatation and blood flow restriction in arterioles of exercising skeletal muscle with ageing in male mice. J Physiol. 2010;588:2269–2282. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WF, Boerman EM, Lange EJ, Lundback SS, Cohen KD. Smooth muscle α1D-adrenoceptors mediate phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction and increases in endothelial cell Ca2+ in hamster cremaster arterioles. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:514–524. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert DG, Thomas GD. α-Adrenoceptor constrictor responses and their modulation in slow-twitch and fast-twitch mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2005;563:821–829. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin MH, Armstrong RB. Adrenoreceptor effects on rat muscle blood flow during treadmill exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1987;62:1465–1472. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.4.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luff SE. Ultrastructure of sympathetic axons and their structural relationship with vascular smooth muscle. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1996;193:515–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00187924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. The influence of the sympathetic nervous system on individual vessels of the microcirculation of skeletal muscle of the rat. J Physiol. 1982;332:169–186. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WH, 3rd, Coggan AR, Spina RJ, Saffitz JE. Effects of fiber type and training on β-adrenoceptor density in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1989a;257:E736–E742. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.257.5.E736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WH, 3rd, Murphree SS, Saffitz JE. β-adrenergic receptor distribution among muscle fiber types and resistance arterioles of white, red, and intermediate skeletal muscle. Circ Res. 1989b;64:1096–1105. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.6.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillivray-Anderson KM, Faber JE. Effect of acidosis on contraction of microvascular smooth muscle by α1- and α2-adrenoceptors. Implications for neural and metabolic regulation. Circ Res. 1990;66:1643–1657. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medgett IC, Langer SZ. Heterogeneity of smooth muscle alpha adrenoceptors in rat tail artery in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;229:823–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellander S. Interaction of local and nervous factors in vascular control. Angiologica. 1971;8:187–201. doi: 10.1159/000157894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AW, Bearden SE, Segal SS. Regional activation of rapid onset vasodilatation in mouse skeletal muscle: regulation through α-adrenoreceptors. J Physiol. 2010;588:3321–3331. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.193672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JL. Blockade of noradrenaline-induced constrictions by yohimbine and prazosin differs between consecutive segments of cutaneous arteries in guinea-pig ears. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:1105–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyanagi M, Faber JE, Nishigaki K. Differential activation of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors on microvascular smooth muscle during sympathetic nerve stimulation. Circ Res. 1991;68:232–244. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.1.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DS, Robinson ED, Butler JL. Is active skeletal muscle functionally vasoconstricted during dynamic exercise in conscious dogs? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;272:R386–R391. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.1.R386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Proctor DN, Joyner MJ. Skeletal muscle mass and the reduction of

in trained older subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:1411–1415. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.5.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

in trained older subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:1411–1415. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.5.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Remensnyder JP, Mitchell JH, Sarnoff SJ. Functional sympatholysis during muscular activity. Observations on influence of carotid sinus on oxygen uptake. Circ Res. 1962;11:370–380. doi: 10.1161/01.res.11.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell S. Neuronal control of microvessels. Annu Rev Physiol. 1980;42:359–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.42.030180.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmeier JB, Fritzlar SJ, Dinenno FA, Joyner MJ. Exogenous NO administration and α-adrenergic vasoconstriction in human limbs. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2370–2374. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00634.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal SS. Integration of blood flow control to skeletal muscle: key role of feed arteries. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;168:511–518. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GD, Segal SS. Neural control of muscle blood flow during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:731–738. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00076.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GD, Zhang W, Victor RG. Impaired modulation of sympathetic vasoconstriction in contracting skeletal muscle of rats with chronic myocardial infarctions: role of oxidative stress. Circ Res. 2001;88:816–823. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.089341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans PB, Chiu AT, Thoolen MJ. Calcium handling in vasoconstriction to stimulation of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1987;65:1649–1657. doi: 10.1139/y87-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte PM, Verbeuren TJ, Webb RC. Local modulation of adrenergic neuroeffector interaction in the blood vessel well. Physiol Rev. 1981;61:151–247. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanTeeffelen JW, Segal SS. Interaction between sympathetic nerve activation and muscle fibre contraction in resistance vessels of hamster retractor muscle. J Physiol. 2003;550:563–574. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.038984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray DW, Fadel PJ, Smith ML, Raven P, Sander M. Inhibition of α-adrenergic vasoconstriction in exercising human thigh muscles. J Physiol. 2004;555:545–563. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.054650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]