Abstract

The arrival of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents has led to a dramatic improvement in the care of patients with Crohn's disease. Since these medications do not work in everyone, and are associated with rare, but serious side effects, we want to selectively treat patients who have the highest chance of responding. A number of variables have been studied to determine their association with response to anti-TNF agents. Clinical parameters include patient characteristics, smoking status and disease phenotype, and biologic markers include C-reactive protein, serum TNF levels and immune responses to microbial antigens. More recently, research has focused on genetics to identify polymorphisms associated with treatment response. Results from individual studies of these factors have not yet allowed for solid clinical applicability. However, further work in this area along with multivariate clinical prediction modeling may soon allow us to deliver ‘personalized medicine’ by predicting individualized treatment response in patients with Crohn's disease.

Introduction

Over the past ten years there have been remarkable strides for the treatment of patients with Crohn's disease. Specifically, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of inflixi-mab in 1998, and more recently adalimumab in 2005 and certolizumab pegol in 2008 have led to a better quality of life in many patients with Crohn's disease. The mechanism of action of these anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents is likely multi factorial. The antibody may bind and clear soluble TNF, and also bind to cell-bound TNF that can induce apoptosis of cells expressing membrane TNF. Despite different formulations and some difference in mechanism of action (certolizumab pegol does not appear to induce apoptosis as do infliximab and adalimu-mab), the efficacy of these three medications appears to be remarkably similar. Across agents, in the pivotal clinical trials for Crohn's disease the initial response rate was approximately 60%, with about 30% of these responders maintaining remission out to one year [Hanauer et al. 2002; Colombel et al. 2007; Schreiber et al. 2007a].

Although those who do respond can enjoy a dramatic improvement in their disease status, there are still many patients who respond sub optimally or not at all. This may be due to the fact that they do not have active inflammatory Crohn's disease (e.g., they have fibrotic disease or irritable bowel syndrome), have received suboptimal dosing, or that the mechanism of their disease is less dependent on TNF and therefore is less responsive to anti-TNF agents. Since these medications have multiple reported potential side effects, the benefit to risk ratio is narrow [Siegel et al. 2006]. Therefore, to optimize this ratio we want to use these medications in those who have the highest chance of responding. Recently, there have been exciting developments in finding factors that can help predict who is more likely to respond to anti-TNF agents. We hope that in the near future this will allow us to be more elegant in targeted patient selection.

Factors contributing to predicting a response to anti-TNF agents

Clinical parameters

There have been a number of individual patient characteristics evaluated for an association with a response to anti-TNF agents. Disease duration has been evaluated with the hypothesis that patients with shorter disease duration will have a better response to early treatment. This was demonstrated in post-hoc analyses from large clinical trials where those with a disease duration shorter than two years had a higher chance of responding to anti-TNFs than those with more long-standing disease [Sandborn et al. 2006; Schreiber et al. 2007b]. This was also demonstrated in pediatric populations [Lionetti et al. 2003], and the significantly higher response rates in the REACH trial of infliximab in children [Hyams et al. 2007] (as compared to adult response rates) may also be a result of earlier intervention or a younger age of treatment [Vermeire et al. 2002a]. There was no association seen in other studies evaluating disease duration and age [Parsi et al. 2002; Arnott et al. 2003; Fefferman et al. 2004]. New treatment algorithms suggest that early combination anti-TNF and immunomodulator therapy will yield better outcomes than waiting until immunomodulator monotherapy failure [D'haens et al. 2008]. With some conflicting results, it is still not clear if patients with a shorter duration of disease will have a more favorable response to anti-TNFs. Intuitively though, treating patients earlier when inflammatory disease predominates over fibrosis is appealing.

Disease phenotype may offer some predictive value in who will respond to anti-TNF medications. Patients with isolated Crohn's colitis may respond better [Vermeire et al. 2002a; Arnott et al. 2003], and those with intestinal strictures and prior surgery have been shown to have a lower response rate [Vermeire et al. 2002a; Weinberg et al. 2002]. Others have not found an association between phenotype and response [Parsi et al. 2002; Orlando et al. 2005], which may be due to a true lack of an association, underpowered evaluations or different study designs.

Smoking is known to negatively influence disease course, and patients who are smokers have been shown to have lower response rates than nonsmoking Crohn's patients. Parsi et al. assessed 100 patients with Crohn's disease [Parsi et al. 2002]. They were evaluated based on smoking status and the presence of either inflammatory or fistulizing disease. Smokers (>5 cigarettes per day for >6 months) with inflammatory disease were less likely to respond to infliximab [OR¼0.09 (0.02–0.38)], but this was not seen in those with fistulizing disease. Another study also found a negative association with smoking, with a 1 year relapse rate after receiving inflixi-mab of 100% in smokers compared to 40% in nonsmokers (p¼0.0026) [Arnott et al. 2003]! Others did not find the same relationship [Vermeire et al. 2002a; Fefferman et al. 2004; Orlando et al. 2005]. Encouraging Crohn's disease patients to stop smoking is always a good idea, but based on these data the role of smoking as a predictor of response in Crohn's disease is unclear. Table 1 summarizes these results, in addition to data regarding biochemical, serologic and genetic markers associated with anti-TNF response.

Table 1.

Summary of studies investigating factors predicting infliximab response.

| Parameter | Study author (cohort size) | Association in terms of response to infliximab | |

| Clinical/patient characteristics | Duration of disease | Lionetti et al. [Lionetti et al. 2003] (22 paediatric) | Positive association with short disease duration |

| Parsi et al. [Parsi et al. 2002] (100) | No association | ||

| Arnott et al. [Arnott et al. 2003] (74) | No association | ||

| Fefferman et al. (200) | No association | ||

| Young age | Vermeire et al. [Vermeire et al. 2002a] (240) | Positive association | |

| Orlando et al. [Orlando et al. 2005] (573) | No association | ||

| Fefferman et al. (200) | No association | ||

| Disease site | Arnott et al. [Arnott et al. 2003] (74) | Positive association with colonie disease | |

| Vermeire et al. [Vermeire et al. 2002a] (240) | Positive association with isolated colitis and negative with isolated ileitis | ||

| Parsi et ai [Parsi et ai 2002] (100) | No association | ||

| Orlando et al. [Orlando et al. 2005] (573) | No association | ||

| Intestinal stricture | Weinberg et al. [Weinberg et al. 2002] (127) | Negative association | |

| Previous surgery | Vermeire et al. [Vermeire et al. 2002a] (240) | Negative association | |

| Arnott et al. [Arnott et al. 2003] (74) | No association | ||

| Orlando et al. [Orlando et al. 2005] (573) | Negative association | ||

| Smoking | Parsi et ai [Parsi et ai 2002] (100) | Negative impact on response rate and duration | |

| Arnott et al. [Arnott et al. 2003] (74) | Negative association | ||

| Vermeire et al. [Vermeire et al. 2002a] (240) | No association | ||

| Orlando et al. [Orlando et al. 2005] (573) | No association | ||

| Fefferman et al. (200) | No association | ||

| Biochemical and immunological parameters | C-reactive protein | Louis et al. [Louis et al. 2002] (153) | Positive association |

| pANCA/ASCA/sANCA | Esters et al. [Esters et al. 2002] (279) | No association (+pANCA, –ASCA: trend towards negative response, p = 0.07) | |

| Taylor et al. [Taylor et al. 2001] (59) | sANCA positive association | ||

| Arnott et al. [Arnott et al. 2003] (74) | No association | ||

| Pharmacogenomics | TNF and TNFR polymorphism | Mascheretti et al. [Mascheretti et al. 2002b] (90/444) | No association |

| Pierik et al. [Pierik et al. 2004] (166) | No association | ||

| NOD2 | Mascheretti et al. [Mascheretti et al. 2002a] (534) | No association | |

| Vermeire ef a/. [Vermeire ef a/. 2002b] (245) | No association | ||

| IBD5 (5q31) | Urcelay et al. [Urcelay et al. 2005] | Negative association | |

| FcyRllla genotype | Louis et al. [Louis et al. 2004] (200) | Positive (V/V genotype) association | |

| Apoptosis genes (Fas ligand-843CC/CT, caspase-9 93 TT) | Hlavaty et al. [Hlavaty et al. 2005] (247) | Positive association | |

| Apoptosis genes (Fas ligand-843 TT) | Hlavaty et al. [Hlavaty et al. 2007] (247) | Negative association (overcome by 6MP/AZA) |

Adapted from Chaudhary and Ghosh (2005] [Chaudhary et al. 2005] and reproduced with permission from Elsevier. pANCA, peri-nuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; ASCA, anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody; sANCA, speckled anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR, tumor necrosis factor receptor; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; 6MP, 6-mercaptopurine; AZA, azathioprine.

Biologic markers

Biologic markers such as cytokine levels, C-reactive protein (CRP) and anti microbial antigens have been studied. In a small study of 36 patients with fistulizing Crohn's disease, TNF, IL-1ß and IL-6 levels were measured before and after treatment with infliximab. In this 10 week study, patients who did not respond to infliximab had higher baseline TNF levels [Martinez-Borra et al. 2002]. A larger study of 226 patients did not find a relationship between treatment response and TNF levels [Louis et al. 2002]. In this same study, elevated CRP levels were shown to predict response to infliximab [(76% of patients with a baseline CRP >5mg/L responded to infliximab compared to only 46% of normal CRP patients (p = 0.004)]. This was also observed in an early study of certolizumab pegol where patients with an elevated CRP responded more effectively to anti-TNF agents than those with lower baseline levels [Schreiber et al. 2005]. Whether an elevated CRP is truly predictive of response to anti-TNF or simply a marker that symptoms are truly due to active inflammatory disease remain to be proven.

There has been enthusiasm to study antineutro-phil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA) as predictors of response to anti-TNFs. In a study of 269 Crohn's disease patients, using a combination of a positive perinuclear (p)ANCA and a negative ASCA there was a nonstatistically significant trend (p = 0.067) towards prediction of a negative response to infliximab [Esters et al. 2002]. Another study did show a statistically significant association between speckled ANCA (sANCA) and a better anti-TNF response when compared to patients with other ANCA staining patterns [pANCA or cytoplasmic (cANCA)] (p = 0.003 at 4 weeks) [Taylor et al. 2001]. In ulcerative colitis these markers may also be helpful, with a poorer infliximab response in patients with a positive pANCA and negative ASCA [Ferrante et al. 2007]. Although these data suggest that a positive pANCA and negative ASCA could predict nonresponse to anti-TNF, we have not yet seen data convincing enough to use this routinely in clinical practice.

Genetics

With the rapid progression of the understanding of the association of genetics and Crohn's disease, searching for genetic markers to predict response to therapy is appealing.

Results have thus far been mixed, but there is promise for future clinical utility. TNF-α gene polymorphisms have been a focus of work on this topic. Taylor et al. showed that patients homozygous for a TNF-α polymorphism (LTA NcoI-TNFc-aa13L-aa26 1-1-1-1 haplotype) were not responsive to infliximab [Taylor et al. 2001] and Pierik and colleagues saw a lower response to infliximab in patients TNFR-1 + 36 [Pierik et al. 2004]. Subsequent studies have not corroborated the relationship between TNF gene polymorphisms and impaired infliximab response in Crohn's patients [Mascheretti et al. 2002b; Louis et al. 2004]. Based on the association of the NOD2 gene and Crohn's disease efforts have been made to identify a relationship between NOD2 response to anti-TNFs. Thus far, a relationship has not been established [Mascheretti et al. 2002a; Vermeire et al. 2002b]. However, the IBD5 gene (5q31) is associated with a negative response to infliximab [Urcelay et al. 2005] and the IgG Fc receptor IIIa (FcyRIIIa) gene (V or F, expressed on macrophages and natural killer cells and triggers cell activation of cytotoxic immune cells) showed an increased response, with homozygous V/V patients having a 100% biologic response compared to 70% of others [Louis et al. 2004].

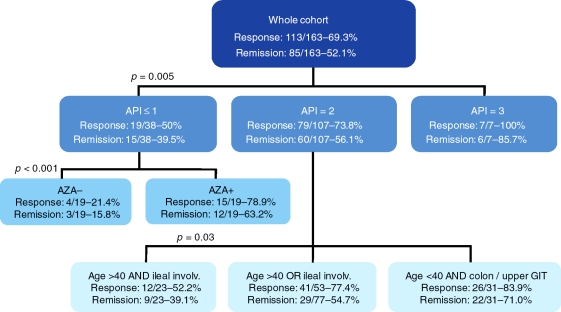

Some very interesting work from Belgium focuses on polymorphisms in apoptosis genes to predict response to infliximab (as above, both infliximab and adalimumab have been shown to induce cellular apoptosis) [Hlavaty et al. 2005]. They developed an apoptosis pharmacogenetic index (API) based on three single nucleotide poly-pmorphisms (SNPs): Fas ligand-843 C/T; Fas-670 G/A; Caspase9 93 C/T [Hlavaty et al. 2007]. Points were given for an individual patients’ profile to calculate their API ranging from 0-3. Clear differences were seen with higher API scores leading to improved response and remission rates in both luminal (p = 0.005, response, p = 0.02, remission) and fistulizing (p = 0.054, response; remission, p = 0.045) disease. Subsequently, they used these results in combination with clinical parameters to develop an algorithmic predictive model for response to infliximab (Figure 1). Although this was a relatively small retrospective study, promising ideas come from this approach. For example, for patients in the API = 3 group, it may not be necessary to consider use of concomitant immunomodulators as the response rate to infliximab is already so high. In contrast, in the API ≤ 1 group, patients taking concomitant azathioprine had a 63.2% rate of remission compared to a 15.8% remission rate with infliximab monotherapy.

Figure 1.

Proposed treatment algorithm for luminal Crohn's disease based on the apoptosis pharmacogenetic index [Hlavaty et al. 2007]. Reproduced with permission from Wiley Interscience. API, apoptosis pharmacogenetic index; AZA, azathioprine; GIT, gastrointestinal tract.

Imaging

The understanding of apoptosis as a mechanism of action of infliximab has also led to other techniques for predicting response. Van den Brande and colleagues used (99m)Technetium-annexin V single-photon emission computer tomography (SPECT) for real-time visualization of apoptosis in patients with Crohn's disease [Van Den Brande et al. 2007]. Increase in uptake could be measured within 24 hours of an infliximab infusion, and those with higher uptake values of tech-netium had higher response rates compared to nonresponders (p = 0.03). This novel approach to quickly determine likelihood of future response can help in both decreasing unnecessary drug exposure and saving costs.

Modeling complex factors

Making decisions on who should be treated with anti-TNF agents has typically been left up to clinical judgment and an attempt to assimilate all of the above complex data into a gestalt of which patients need these medications. As more information become available and further predictive factors are discovered, help from computer modeling can assist in making good decisions, and just as importantly, clearly communicating our reasoning to patients. System dynamics analysis (SDA) is a methodology that addresses complex interactions and predicts outcomes based on available data and the consequences associated with expected and unexpected associations. This technique, primarily used in fields other than medicine, has the advantage over traditional multiple logistic regression is in its ability to incorporate the inherent dynamic complexity of interactions and graphically convey the outcomes. SDA is being used in Crohn's disease to provide individualized prediction of outcomes of disease and treatment [Siegel et al. 2009]. Ultimately, this model, using many of the variables above to developed simple output graphs will be able to be used at the bedside to demonstrate to patients their predicted course of disease severity and how this can be altered with biologic therapy. This is a first step in taking complicated (and oftentimes conflicting) statistical results and helping patients understand how their disease and treatment may affect them over time.

Conclusion

The anti-TNF agents are the first of what we expect to be many in the class of biologic agents. In addition to natalizumab, an alpha-4-integrin molecule that was approved for Crohn's disease in 2008, multiple others are currently in clinical trials. The above early work with anti-TNFs gives us a vision of the future of ‘personalized medicine’ that we can strive for over the next few years. These agents work, but not in everyone. To limit toxicity, save cost and more precisely deliver effective treatment, the future of this line of research is critical.

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Siegel is supported by a CCFA career development award and by Grant Number K23DK078678 from the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Corey Siegel has served as a consultant or on a scientific advisory board for Abbott, Elan and UCB; received honoraria for speaking from Abbott, P&G, and UCB. Dr. Gil Melmed has served on the speakers’ bureau for Abbott, received research funding from Centocor and has participated on scientific advisory boards for UCB.

Contributor Information

Corey A. Siegel, Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, USA corey.a.siegel@hitchcock.org

Gil Y. Melmed, Division of Gastroenterology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA

References

- Arnott I.D., Mcneill G., Satsangi J. (2003) An analysis of factors influencing short-term and sustained response to infliximab treatment for Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 17:1451–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary R., Ghosh S. (2005) Prediction of response to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis 37:559–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombel J.F., Sandborn W.J., Rutgeerts P., Enns R., Hanauer S.B., Panaccione R.et al. (2007) Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn's disease: the charm trial. Gastroenterology 132:52–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'haens G., Baert F., Van Assche G., Caenepeel P., Vergauwe P., Tuynman H.et al. (2008) Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet 371:660–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esters N., Vermeire S., Joossens S., Noman M., Louis E., Belaiche J.et al. (2002) Serological markers for prediction of response to anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 97:1458–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fefferman D.S., Lodhavia P.J., Alsahli M., Falchuk K.R., Peppercorn M.A., Shah S.A.et al. (2004) Smoking and immunomodulators do not influence the response or duration of response to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 10:346–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante M., Vermeire S., Katsanos K.H., Noman M., Van Assche G., Schnitzler F.et al. (2007) Predictors of early response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 13:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanauer S.B., Feagan B.G., Lichtenstein G.R., Mayer L.F., Schreiber S., Colombel J.F.et al. (2002) Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the accent i randomised trial. Lancet 359:1541–1549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavaty T., Ferrante M., Henckaerts L., Pierik M., Rutgeerts P., Vermeire S. (2007) Predictive model for the outcome of infliximab therapy in Crohn's disease based on apoptotic pharmacogenetic index and clinical predictors. Inflamm Bowel Dis 13:372–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavaty T., Pierik M., Henckaerts L., Ferrante M., Joossens S., Van Schuerbeek N.et al. (2005) Polymorphisms in apoptosis genes predict response to infliximab therapy in luminal and fistulizing Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 22:613–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyams J., Crandall W., Kugathasan S., Griffiths A., Olson A., Johanns J.et al. (2007) Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease in children. Gastroenterology 132:863–873; quiz 1165-1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti P., Bronzini F., Salvestrini C., Bascietto C., Canani R.B., De Angelis G.L.et al. (2003) Response to infliximab is related to disease duration in paediatric Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 18:425–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis E., El Ghoul Z., Vermeire S., Dall'ozzo S., Rutgeerts P., Paintaud G.et al. (2004) Association between polymorphism in Igg Fc receptor Iiia coding gene and biological response to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 19:511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis E., Vermeire S., Rutgeerts P., De Vos M., Van Gossum A., Pescatore P.et al. (2002) A positive response to infliximab in Crohn disease: association with a higher systemic inflammation before treatment but not with -308 Tnf gene polymorphism. Scand J Gastroenterol 37:818–824 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Borra J., Lopez-Larrea C., Gonzalez S., Fuentes D., Dieguez A., Deschamps E.M.et al. (2002) High serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels are associated with lack of response to infliximab in fistulizing Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 97:2350–2356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascheretti S., Hampe J., Croucher P.J., Nikolaus S., Andus T., Schubert S.et al. (2002a) Response to infliximab treatment in Crohn's disease is not associated with mutations in the Card15 (Nod2) gene: an analysis in 534 patients from two multicenter, prospective Gcp-level trials. Pharmacogenetics 12:509–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascheretti S., Hampe J., Kuhbacher T., Herfarth H., Krawczak M., Folsch U.R.et al. (2002b) Pharmacogenetic investigation of the Tnf/Tnf-receptor system in patients with chronic active Crohn's disease treated with infliximab. Pharmacogenomics J 2:127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando A., Colombo E., Kohn A., Biancone L., Rizzello F., Viscido A.et al. (2005) Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn's disease: predictors of response in an italian multicentric open study. Dig Liver Dis 37:577–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsi M.A., Achkar J.P., Richardson S., Katz J., Hammel J.P., Lashner B.A.et al. (2002) Predictors of response to infliximab in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 123:707–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierik M., Vermeire S., Steen K.V., Joossens S., Claessens G., Vlietinck R.et al. (2004) Tumour necrosis factor-alpha receptor 1 and 2 polymorphisms in inflammatory bowel disease and their association with response to infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 20:303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandborn W.J., Colombel J.F., Panes J., Scholmerich J., Mccolm J., Schreiber S. (2006) Higher remission and maintenance of response rates with subcutaneous monthly certolizumab pegol in patients with recent-onset Crohn's disease: data from precise 2. Am J Gastroenterol 101:S434–S435 [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S., Khaliq-Kareemi M., Lawrance I.C., Thomsen O.O., Hanauer S.B., Mccolm J.et al. (2007a) Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 357:239–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S., Reinisch W., Colombel J.F., Sandborn W.J., Hommes D.W., Li J.et al. (2007b) Early Crohn's disease shows high levels of remission to therapy with adalimumab: sub-analysis of charm. Gastroenterology 132:A-147 [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S., Rutgeerts P., Fedorak R.N., Khaliq-Kareemi M., Kamm M.A., Boivin M.et al. (2005) A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of certolizu-mab pegol (Cdp870) for treatment of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 129:807–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel C.A., Hur C., Korzenik J.R., Gazelle G.S., Sands B.E. (2006) Risks and benefits of infliximab for the treatment of Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 4:1017–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel C.A., Siegel L.S., Hyams J., Kugathasan S., Markowitz J., Rosh J.R.et al. (2009) A prediction tool to help children with Crohn's disease and their parents understand individualized risks of disease complications and response to therapy. Gastroenterology. Chicago, IL: DDW [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K.D., Plevy S.E., Yang H., Landers C.J., Barry M.J., Rotter J.I.et al. (2001) Anca pattern and lta haplotype relationship to clinical responses to anti-tnf antibody treatment in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 120:1347–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urcelay E., Mendoza J.L., Martinez A., Fernandez L., Taxonera C., Diaz-Rubio M.et al. (2005) Ibd5 Polymorphisms in inflammatory bowel disease: association with response to infliximab. World J Gastroenterol 11:1187–1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Brande J.M., Koehler T.C., Zelinkova Z., Bennink R.J., Te Velde A.A., Ten Cate F.J.et al. (2007) Prediction of antitumour necrosis factor clinical efficacy by real-time visualisation of apoptosis in patients with Crohn's disease. Gut 56:509–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeire S., Louis E., Carbonez A., Van Assche G., Noman M., Belaiche J.et al. (2002a) Demographic and clinical parameters influencing the short-term outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor (Infliximab) treatment in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 97:2357–2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeire S., Louis E., Rutgeerts P., De Vos M., Van Gossum A., Belaiche J.et al. (2002b) Nod2/ Card15 does not influence response to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 123:106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A.M., Rattan S., Lewis J.D., Su C., Katzka D.A., Deren J. (2002) Strictures and response to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 97:S255 [Google Scholar]