Abstract

There is increasing evidence that inflammation or a disturbance of the flora within the gut might contribute to the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), at least in a proportion of cases. As a consequence it has been speculated that, as some probiotic bacteria have a range of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, the administration of such organisms might prove to be beneficial in this condition. It has to be acknowledged that the quality and design of trials of probiotics in IBS has been somewhat variable but the majority have shown benefit, although some bacteria appear to be more effective than others. More recent studies using Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 and Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173-010 have given particularly encouraging results. Issues for the future include determining which organisms are most effective, defining optimal doses, comparing methods of delivery and assessing the role of mixtures or the addition of prebiotics.

Keywords: irritable bowel syndrome, probiotics, bifidobacteria

Rationale for probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome

As long ago as 1962, it was recognised that some cases of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) appeared to follow an acute gastrointestinal infection [Chaudhary and Truelove, 1962]. This concept of postinfectious IBS has been confirmed in a number of subsequent studies with between 4% and 31% of patients with IBS dating their symptoms from an infective episode [Marshall et al. 2006; Rodriguez and Ruigomez, 1999; Neal et al. 1997; McKendrick and Read, 1994]. The mechanism by which infection could lead to continuing symptoms is not fully understood but it has been suggested that it might be due to persisting inflammation [Spiller, 2004a, 2004b]. Evidence in favour of this hypothesis has emerged from a number of histological studies of the mucosa in patients with IBS [Barbara et al. 2004; Chadwick et al. 2002; Spiller et al. 2000; Gwee et al. 1999] although in one there was also inflammation in patients who denied any antecedent enteric infection [Chadwick et al. 2002]. Another situation which seems to predispose to IBS is the previous use of antibiotics [Maxwell et al. 2002; Mendall and Kumar, 1998], particularly if they are used on a long-term basis such as in patients with acne or chronic sinus infection. This might result in a change in the bacterial flora of the gut and studies both using culture or molecular techniques suggest that there might be subtle differences in patients with IBS compared with healthy controls [Kassinen et al. 2007; Matto et al. 2005; Malinen et al. 2005; Si et al. 2004]. It has also been reported that small bowel bacterial overgrowth may be important in some patients with IBS although this particular topic remains somewhat controversial [Bratten et al. 2008; Majewski and McCallum, 2007; Posserud et al. 2007; Pimentel et al. 2003b, 2000]. However, it is possible that at least a proportion of patients might suffer from this problem. In contrast to the observation that IBS can follow the use of antibiotics, there is now some evidence that the administration of a nonabsorbable antibiotic can actually lead to symptom reduction [Pimentel et al. 2006; Sharara et al. 2006]. All these data indicate that inflammation or imbalance of the bacterial flora of the gut might play a part in the pathogenesis of IBS. It is against this background that the possibility that probiotics might have a beneficial effect in IBS has been entertained. Probiotics have been shown to have a whole range of beneficial effects which are listed in Box 1. The most commonly used pro-biotic organisms are the lactobacillae and bifido-bacteria and it is important to note that different organisms can have completely different activity so that, for instance, one type of bifido-bacterium may not exhibit the same properties as another.

Probiotics in IBS

Table 1 [Guyonnet et al. 2007; Gawronska et al. 2007; Niv et al. 2005; Bausserman and Michail, 2005; Sen et al. 2002; Niedzielin et al. 2001; Nobaek et al. 2000; O'Sullivan and O'Morain, 2000; Halpern et al. 1996; Gade and Thorn, 1989] lists the results of controlled clinical trials that have been undertaken using single probiotic preparations. Table 2 [Drouault-Holowacz et al. 2008; Enck et al. 2008; Kajander et al. 2008, 2005; Sinn et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2008; Y.G. Kim et al. 2006; H.J. Kim 2005, 2003] documents studies using mixtures of organisms, while Table 3 shows the composition of these various mixtures. Unfortunately, there is considerable variation in trial design and outcome measures but it is clear that different symptoms are improved depending on the preparation used and that some products appear to be more effective than others. However, the results are generally positive with 15 of the 19 studies listed showing at least some effect.

Table 1.

Controlled dinicaL trials of single probiotic preparations in irritable bowel syndrome.

| Organism | n | Outcome | Reference |

| L. plantarum | 60 | ↓pain, flatulence | Nobaek et al. (2000) |

| L. plantarum | 20 | ↓ pain | Niedzielin et al. (2001) |

| L. plantarum | 12 | negative | Sen et al. (2002) |

| L. GG | 25 | negative | O'Sullivan and O'Morain (2000) |

| L. GG | 50 | ↓ bloating | Bausserman and Michail (2005) |

| L GG | 104 | ↓ pain | Gawronska et al. (2007) |

| L. reuterii | 54 | negative | Niv et al. (2005) |

| L. acidophilus | 18 | ↓ global score | Halpern et al. (1996) |

| S. faecium | 54 | ↓ global score | Gade et al. (1989) |

| B. lactis | 274 | ↓ digestive symptoms | Guyonnet et al. (2007) |

B., Bifidobacterium; L, Lactobacillus; n, number of patients; S., Streptococcus.

Table 2.

Controlled clinical trials of probiotic mixtures in irritable bowel syndrome.

| Organism | n | Outcome | Reference |

| VSL#3 (× 8) | 25 | ↓ bloating | Kim et al. (2003) |

| VSL#3 (× 8) | 48 | ↓ flatulence | Kim et al. (2005) |

| Mixture (× 4) | 103 | ↓ global score | Kajander et al. (2005) |

| Mixture (× 4) | 86 | ↓ global score | Kajander et al. (2008) |

| Mixture (× 4) | 52 | ↓ global score | Williams et al. (2008) |

| Mixture (× 4) | 106 | negative | Drouault-Holowacz et al. (2008) |

| Mixture (× 2) | 40 | ↓ pain | Kim et al. (2006) |

| Mixture (× 2) | 40 | ↓ pain | Sinn et al. (2008) |

| Mixture (× 2) | 297 | ↓ global score | Enck et al. (2008) |

n, number of patients.

Table 3.

Composition of probiotic mixtures from TabLe 2.

| ×8 | 3 bifidobacteria, 4 Lactobacillae, 1 streptococcus |

| ×4 | 2 Lactobacillae, 1 bifidobacterium, 1 propionibacterium |

| ×4 | 2 Lactobacillae, 2 bifidobacterium |

| ×4 | 2 Lactobacillae, 1 bifidobacterium, 1 streptococcus |

| ×2 | 1 B. subtilis, 1 streptococcus |

| ×2 | 2 Lactobacillae |

| ×2 | 1 enterococcus, 1 E.coli (cell fragments) |

Box 1. Some properties of probiotics.

Enhance host's anti-inflammatory and immune response

Stimulate anti-inflammatory cytokines

Improve epithelial cell barrier

Exhibit epithelial adhesion

Inhibit bacterial translocation

Inhibit growth of pathogens (e.g. salmonella)

Inhibit adhesion of viruses (e.g. rotavirus)

Reduce hypermotility (animal model)

Reduce visceral hypersensitivity (animal model)

Inactivate bile acids

-

Elaborate active proteins and metabolites with following characteristics:

immune modulatory activity

proteolytic/bacteriocidal activity

toxin binding activity.

Specific studies of probiotics in IBS

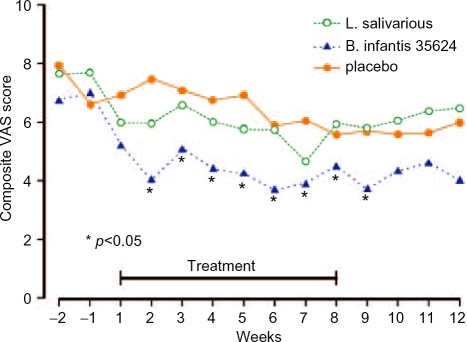

Recently, the group based at the University of Cork isolated a bifidobacterium (B. infantis 35624) which they considered to have promise in IBS. In 2005 they reported a study comparing this organism at a strength of 1 × 1010 cells in 100 ml of malted milk per day with Lactobacillus salivarius, at a similar concentration, in a similar volume of malted milk per day or 100 ml of malted milk placebo [O'Mahony et al. 2005]. Twenty-five patients were recruited to each group and studied for 8 weeks. Figure 1 compares the results for the three groups in terms of a composite IBS symptom score. As can be seen, there was a significant advantage for the bifidobacterium compared with the other two groups and the beneficial effect appeared to last after treatment was discontinued. The authors also studied the effect of treatment on the ratio of an anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) to a proinflammatory cytokine (IL-12). This ratio appeared to be in a proinflammatory state before treatment and this became normalised after administration of the bifidobacterium. Thus, this particular probiotic appears to have promising effects in IBS but a milk delivery system is obviously cumbersome and it would be far better if this could be given in a capsule. As a consequence, a dose-ranging study was undertaken of B. infantis 35624 in capsule form [Whorwell et al. 2006].

Figure 1.

Effect of Bifidobacterium infantis 35624, Lactobaccilus salivarius or placebo on composite score in irritable bowel syndrome.

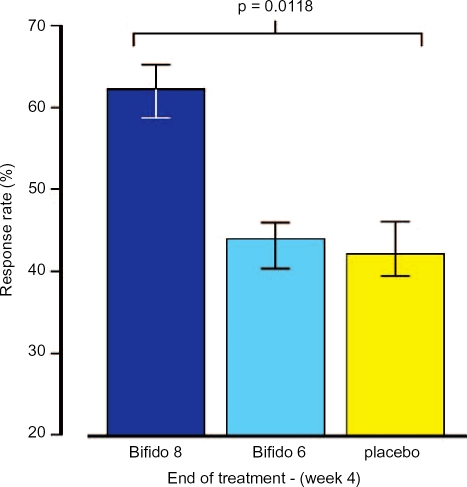

Three-hundred-and-sixty-two female patients with uncomplicated IBS, irrespective of whether they had diarrhoea or constipation, were randomly allocated to take one of four possible treatments for 4 weeks. These were one capsule containing either B.infantis 35624, 1 × 1010, 1 × 108 or 1 × 106 colony forming units per capsule, or matching placebo. At the end of the study it became apparent that the 1010 dose of the pro-biotic, which was the dose used in the original milk-based study, was ineffective. Further investigation of this problem revealed that the contents of the capsule failed to disperse because the organism secreted an intensely hygroscopic exo-polysaccharide coating rendering the preparation inactive. Analysis of the data for the other three groups revealed that the 1 × 108 preparation was significantly superior to either the 1 × 106 or placebo. This was seen for all symptoms of IBS and in terms of global outcome, the response rate was over 20% greater than that observed for placebo (Figure 2). In addition to confirming the previous positive results for this probiotic, this study emphasised the slow onset of action of these agents suggesting that short-term studies in this field might fail to detect an effect. Furthermore, bioavailability is obviously another critical consideration as the failure of the 1 × 1010 dose was totally unexpected.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the effect of placebo or Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 at a dose of 1 × 108 (Bifido 8) or 1 × 106 (Bifido 6) colony forming units on global outcome in irritable bowel syndrome.

Possible effects of probiotics in bloating and distension

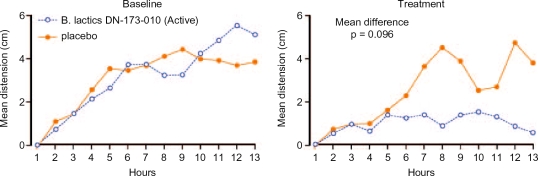

The term ‘bloating’ is usually used to describe the sensation of an increase in abdominal girth, whereas ‘distension’ should only be used when this feeling is accompanied by an actual increase in girth. Both these features are extremely common aspects of IBS, are particularly difficult to treat and often rated as the patient's most intrusive symptom. In order to further understand this phenomenon, the technique of abdominal inductance plethysmography (AIP) has been developed [Reilly et al. 2002; Lewis et al. 2001]. This is based on the principle that a loop of wire has a certain inductance which changes according to the shape of the loop. Therefore, if a wire is stitched into an elasticated belt and placed around the abdomen, any change in girth is detected as a change in inductance and after appropriate manipulation can be subsequently displayed as a measurement. The belt is unobtrusive, can be worn for up to 24 hours and is accurate down to 1mm. Using this technique, it has been shown that 50% of patients who report bloating also exhibit distension and girth can increase by as much as 12 cm during the course of the day [Houghton et al. 2006]. Distension is more common in patients with constipation [Houghton et al. 2006] and is also associated with delayed transit [Agrawal et al. 2006]. Consequently, either relieving constipation or accelerating transit should theoretically lead to an improvement in distension. Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173-010 has previously been shown to accelerate transit [Marteau et al. 2002] and

reduce the subjective symptom of bloating [Guyonnet et al. 2007] and, therefore, might potentially relieve distension which can be measured objectively using AIP. In addition increased methane production from gut bacteria has been associated with constipation in IBS [Pimentel et al. 2003a, 2003c] raising the possibility that alteration of gut flora, perhaps by the use of pro-biotics, may help to relieve this problem although this has not been assessed for B. Iactis DN-173-010.

Thirty-four patients with constipation predominant IBS were randomised to receive either B. Iactis DN-173-010 (1.25 × 1010 colony forming units) in the form of Activia® 125 g twice daily or matching placebo [Agrawal et al. 2008]. Both active and control products were without flavour and had a similar appearance, texture and taste. Distension was measured using AIP at baseline and again after 4 weeks treatment. In addition, small bowel transit was assessed using a test meal and large bowel transit using a radio-opaque marker technique. Symptoms were also recorded. Active treatment resulted in a significant acceleration of small bowel as well as large bowel transit and this was accompanied by a 78% reduction in maximum distension which was significantly greater than the 29% reduction in those receiving the control product. Figure 3 shows the 12 hour AIP data for active and control products during the baseline and treatment phases. With respect to symptoms, abdominal pain and overall IBS score were significantly improved despite the fact that the study was not powered to detect symptom change. Therefore, in addition to supporting the role of this probiotic in improving distension in IBS, this study strengthens the notion that accelerating gastrointestinal transit does reduce this troublesome symptom.

Figure 3.

Recording of abdominal distension over 12 hours before and after treatment with either Bifidobacterium iactis DN-173-010 (Activia®) or placebo.

Conclusion

There seems little doubt that probiotics have some beneficial effects in some patients with IBS. However, they are unlikely to be as potent as pharmacological agents and, therefore, will probably have the greatest utility in patients at the milder end of the spectrum of disease severity. It is important to remember that not all pro-biotics are the same and that they differ in their activity in relation to IBS. Another critical factor is formulation and bioavailability and we need to know whether the products that are being sold to the general public actually have enough viable organisms to make a difference, especially as large doses are required to have a therapeutic effect. A further question that needs resolving is whether mixtures of probiotics are necessarily always a good approach, as there is at least hypothetically, the possibility that some organisms might actually inhibit the activity of others.

IBS is a condition that many patients suffer from over a lifetime and, therefore, the safety of anything they are taking for their condition is of considerable importance. Consequently, the concept of taking a preparation that has perceived benefits on the gut microflora without doing any harm has high patient acceptability.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK has recently reviewed the treatment of IBS and has made the following recommendation about the use of probiotics [NICE 2008]:

Probiotics do not appear to be harmful (unless they come from an unreliable source) and they might benefit people with IBS. They should be advised to take the product for at least four weeks while monitoring the effect.

Conflict of interest statement

Professor Whorwell has received research funding from Danone, Paris, France and Proctor and Gamble, Cincinnati, USA.

References

- Agrawal A., Houghton L.A., Morris J., Reilly B., Guyonnet D., Goupil Feuillerat N.et al. (2008) Clinical trial: the effects of a fermented milk product containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173-010 on abdominal distension and gastrointestinal transit in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation, Aliment Pharmacol Ther Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed]

- Agrawal A., Whorwell P., Houghton L. (2006) Is abdominal distension related to delayed small and large transit transit in patients with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 130(Suppl. 2):63216530503 [Google Scholar]

- Barbara G., Stanghellini V., De Giorgio R., Cremon C., Cottrell G.S., Santini D.et al. (2004) Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 126:693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausserman M., Michail S. (2005) The use of lactobacillus GG in irritable bowel syndrome in children: a double-blind randomized control trial. J Pediatr 147:197–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratten J.R., Spanier J., Jones M.P. (2008) Lactulose breath testing does not discriminate patients with irritable bowel syndrome from healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol 103:958–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick V.S., Chen W., Shu D., Paulus B., Bethwaite P., Tie A.et al. (2002) Activation of the mucosal immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 122:1778–1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary N.A., Truelove S.C. (1962) The Irritable colon syndrome. A study of the clinical features, predisposing causes, and prognosis in 130 cases. Q J Med 31:307–322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouault-Holowacz S., Bieuvelet S., Burckel A., Cazaubiel M., Dray X., Marteau P. (2008) A double blind randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination in 100 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 32:147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enck P., Zimmermann K., Menke G., Muller-Lissner S., Martens U., Klosterhalfen S. (2008) A mixture of Escherichia coli (DSM 17252) and Enterococcus faecalis (DSM 16440) for treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome - a randomized controlled trial with primary care physicians. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20:1103–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gade J., Thorn P. (1989) Paraghurt for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. A controlled clinical investigation from general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 7:23–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawronska A., Dziechciarz P., Horvath A., Szajewska H. (2007) A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of lactobacillus GG for abdominal pain disorders in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25:177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyonnet D., Chassany O., Ducrotte P., Picard C., Mouret M., Mercier C.H.et al. (2007) Effect of a fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium animalis DN-173 010 on the health-related quality of life and symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: a multicentre, randomized, doubleblind, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 26:475–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwee K.A., Leong Y.L., Graham C., McKendrick M.W., Collins S.M., Walters S.J.et al. (1999) The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut 44:400–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern G.M., Prindiville T., Blankenburg M., Hsia T., Gershwin M.E. (1996) Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with lacteol fort: a randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial. Am J Gastroenterol 91:1579–1585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton L.A., Lea R., Agrawal A., Reilly B., Whorwell P.J. (2006) Relationship of abdominal bloating to distention in irritable bowel syndrome and effect of bowel habit. Gastroenterology 131:1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajander K., Hatakka K., Poussa T., Farkkila M., Korpela R. (2005) A probiotic mixture alleviates symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a controlled 6-month intervention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 22:387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajander K., Myllyluoma E., Rajilic-Stojanovic M., Kyronpalo S., Rasmussen M., Jarvenpaa S.et al. (2008) Clinical trial: multispecies probiotic supplementation alleviates the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and stabilizes intestinal microbiota. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27:48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassinen A., Krogius-Kurikka L., Makivuokko H., Rinttila T., Paulin L., Corander J.et al. (2007) The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology 133:24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Camilleri M., Mckinzie S., Lempke M.B., Burton D.D., Thomforde G.M.et al. (2003) A randomized controlled trial of a probiotic, VSL#3, on gut transit and symptoms in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 17:895–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Vazquez Roque M.I., Camilleri M., Stephens D., Burton D.D., Baxter K.et al. (2005) A randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination VSL#3 and placebo in irritable bowel syndrome with bloating. Neurogastroenterol Motil 17:687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.G., Moon J.T., Lee K.M., Chon N.R., Park H. (2006) [The effects of probiotics on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome]. Korean J Gastroenterol 47:413–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M.J., Reilly B., Houghton L.A., Whorwell P.J. (2001) Ambulatory abdominal inductance plethysmography: towards objective assessment of abdominal distension in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 48:216–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski M., McCallum R.W. (2007) Results of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth testing in irritable bowel syndrome patients: clinical profiles and effects of antibiotic trial. Adv Med Sci 52:139–142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinen E., Rinttila T., Kajander K., Matto J., Kassinen A., Krogius L.et al. (2005) Analysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCR. Am J Gastroenterol 100:373–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.K., Thabane M., Garg A.X., Clark W.F., Salvadori M., Collins S.M. (2006) Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterborne outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Gastroenterology 131:445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau P., Cuillerier E., Meance S., Gerhardt M.F., Myara A., Bouvier M.et al. (2002) Bifidobacterium animalis strain DN-173 010 shortens the colonic transit time in healthy women: a doubleblind, randomized, controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 16:587–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matto J., Maunuksela L., Kajander K., Palva A., Korpela R., Kassinen A.et al. (2005) Composition and temporal stability of gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome-a longitudinal study in IBS and control subjects. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 43:213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell P.R., Rink E., Kumar D., Mendall M.A. (2002) Antibiotics increase functional abdominal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 97:104–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKendrick M.W., Read N.W. (1994) Irritable bowel syndrome - post salmonella infection. J Infect 29:1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendall M.A., Kumar D. (1998) Antibiotic use, childhood affluence and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 10:59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal K.R., Hebden J., Spiller R. (1997) Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. BMJ 314:779–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE (2008) Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG61#summary

- Niedzielin K., Kordecki H., Birkenfeld B. (2001) A controlled, double-blind, randomized study on the efficacy of Lactobacillus plantarum 299v in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 13:1143–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv E., Naftali T., Hallak R., Vaisman N. (2005) The efficacy of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome - a double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Clin Nutr 24:925–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobaek S., Johansson M.L., Molin G., Ahrne S., Jeppsson B. (2000) Alteration of intestinal microflora is associated with reduction in abdominal bloating and pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 95:1231–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Mahony L., McCarthy J., Kelly P., Hurley G., Luo F., Chen K.et al. (2005) Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology 128:541–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan M.A., O'Morain C.A. (2000) Bacterial supplementation in the irritable bowel syndrome. A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Dig Liver Dis 32:294–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel M., Chow E.J., Lin H.C. (2000) Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 95:3503–3506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel M., Chow E.J., Lin H.C. (2003a) Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome. a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 98:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel M., Kong Y., Park S. (2003b) Breath testing to evaluate lactose intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome correlates with lactulose testing and may not reflect true lactose malabsorption. Am J Gastroenterol 98:2700–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel M., Mayer A.G., Park S., Chow E.J., Hasan A., Kong Y. (2003c) Methane production during lactulose breath test is associated with gastrointestinal disease presentation. Dig Dis Sci 48:86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel M., Park S., Mirocha J., Kane S.V., Kong Y. (2006) The effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 145:557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posserud I., Stotzer P.O., Bjornsson E.S., Abrahamsson H., Simren M. (2007) Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 56:802–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly B.P., Bolton M.P., Lewis M.J., Houghton L.A., Whorwell P.J. (2002) A device for 24 hour ambulatory monitoring of abdominal girth using inductive plethysmography. Physiol Meas 23:661–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L.A., Ruigomez A. (1999) Increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome after bacterial gastroenteritis: cohort study. BMJ 318:565–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S., Mullan M.M., Parker T.J., Woolner J.T., Tarry S.A., Hunter J.O. (2002) Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum 299v on colonic fermentation and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 47:2615–2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharara A.I., Aoun E., Abdul-Baki H., Mounzer R., Sidani S., Elhajj I. (2006) A randomized doubleblind placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin in patients with abdominal bloating and flatulence. Am J Gastroenterol 101:326–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si J.M., Yu Y.C., Fan Y.J., Chen S.J. (2004) Intestinal microecology and quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J Gastroenterol 10:1802–1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinn D.H., Song J.H., Kim H.J., Lee J.H., Son H.J., Chang D.K.et al. (2008) Therapeutic effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus-SDC 2012, 2013 in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 53:2714–2718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller R.C. (2004a) Infection, immune function, and functional gut disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2:445–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller R.C. (2004b) Inflammation as a basis for functional GI disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 18:641–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller R.C., Jenkins D., Thornley J.P., Hebden J.M., Wright T., Skinner M.et al. (2000) Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute campylobacter enteritis and in post-dysenteric irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 47:804–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whorwell P.J., Altringer L., Morel J., Bond Y., Charbonneau D., O'Mahony L.et al. (2006) Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 101:1581–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E., Stimpson J., Wang D., Plummer S., Garaiova I., Barker M.et al. (2008) Clinical trial: a multistrain probiotic preparation significantly reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a double-blind placebo-controlled study, Aliment Pharmacol Ther Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed]