Abstract

Abstract: Traveler's diarrhea (TD) strikes 20—60% of travelers visiting developing countries. It occurs shortly after the return and can be distinguished into two categories: acute and persistent TD. Acute TD, mostly caused by bacterial and viral pathogens, is usually mild and self-limited, and deserves empirical symptomatic and/or antibiotic therapy in selected cases. Fluoroquinolones are progressively superseded in this indication by azithromycin, a well tolerated macrolide active against most bacteria responsible for TD, including the quinolone-resistant species of Campylobacter jejuni that are now pervasive, especially in Southeast Asia and India. Persistent TD in the returning traveler is much rarer than its acute counterpart and may be associated with three types of causes. Persistent infections, among which Giardia and possibly Entamoeba predominate, account for a significant proportion of cases. Postinfectious processes represent a second cause and comprise temporary lactose malabsorption and postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome, now considered a major cause of persistent TD. Finally, apparently unrelated chronic diseases causing diarrhea are occasionally unmasked by TD and represent a third type of persistent TD, among which the well established case of incident inflammatory bowel disease poses intriguing pathogenesis questions. This review discusses recent advances in the field and provides practical recommendations for the management of TD in adult, immunocompetent returning travelers.

Keywords: Campylobacter infections, colonic diseases, diarrhea, dysentery, functional, inflammatory bowel diseases, travel

Introduction

Travelers visiting developing countries frequently experience acute infectious diarrhea, with an incidence rate for a 2-week stay in the order of 20—60% [Steffen et al. 2004; Hill, 2000; Von Sonnenburg et al. 2000]. The problem of diarrhea in a returning traveler encompasses two different clinical pictures. In its common acute form, it is merely a case of traveler's diarrhea (TD) that occurs towards the end of the trip or shortly after the return. A less frequent form, persistent diarrhea of the returning traveler, differs markedly from the former in terms of etiology and management, and will be discussed separately. This article deals with the practical aspects of managing diarrhea in the immunocompetent, adult returning traveler, and will leave aside the topic of prophylaxis.

Acute diarrhea in the returning traveler

Epidemiology and clinical features

The incidence of TD varies among various destinations, and the risk is inversely related to the socioeconomic status of the visited countries [Greenwood et al. 2008]. The relative risks are higher for southern Asia and India, followed by sub-Saharan Africa and South America. In a broad survey of TD, the standardized incidence rate for a 2-week stay ranged from below 40% (Brazil, Caribbean) to more than 60% (India, Kenya) [Steffen et al. 2004].

On the average, TD typically occurs around the fourth or fifth day of stay abroad [Steffen et al. 2004]. ‘Classical TD’ is defined as the voiding of at least three unformed stools per 24 h, with at least one accompanying symptom (nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps or pain, fever, blood in the stool) [Von Sonnenburg et al. 2000]. Classical TD is the most frequent form (40—58%) but milder forms are also taken into account in studies.

Although it may cause considerable incapacitation, since approximately one third of patients are unable to pursue planned activities [Steffen, 2005], TD is rarely severe. Slightly fewer than one in four patients voids more than six unformed stools per day, no more than 8.4% has more than ten movements per day, and between 1% and 7% have subjective fever and/ or blood in their stool [Steffen et al. 2004]. The self-reported mean duration of symptoms is between 61—106 hours. Objective information about the duration of TD may be derived from the placebo arms of randomized controlled trials: in a representative historic study of antibiotics for the treatment of TD, 100% of patients allocated to the placebo arm were in remission after 5 days [Salam et al. 1994]. In a survey of 73,630 short-term travelers, 14 were hospitalized and no fatalities were reported [Steffen et al. 2004].

Etiology and diagnosis

Global data regarding the etiology of TD [Svenungsson et al. 2000; Von Sonnenburg et al. 2000; Ansdell and Ericsson, 1999] may be schematically summarized as follows: bacteria predominate clearly, with both types of Escherichia coli [entero-hemorragic (EHEC), entero-toxigenic (ETEC)] remaining the most frequently associated pathogens [Jiang et al. 2002; Adachi et al. 2001]. A third type of Escherichia coli, diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC) has been associated with 9% of cases of TD [Vargas et al. 1998]. Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella, Shigella and Plesiomonas come next in frequency as bacterial pathogens responsible for TD. Viruses account for up to one-third of cases with noroviruses being the most frequently reported organisms [Chapin et al. 2005; Ko et al. 2005; Jones et al. 2004], and parasitic infections (mostly Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolyticd) are less frequent but well-established causes. A significant regional particularity is that of Southeast Asia and India, where the frequency of Campylobacter is higher and accounts for up to 64% of cases [Tribble et al. 2007].

In about 60% of cases of TD, no infectious pathogens can be isolated from stool using standard methods. Many such cases are probably bacterial, as has been suggested by the results of placebo-controlled therapeutic trials and by the presence of pathogenic ETEC and DAEC genes using PCR in 29% of culture-negative stools from patients with TD acquired in Central America and India [Meraz et al. 2008].

The self-limited nature of TD makes it unnecessary to document a specific pathogen in most cases, so that systematic stool cultures are not recommended. Stool cultures may be considered, however, in patients with fever or colitis symptoms, in patients with comorbidities that increase the risk of complications, and in patients with coexisting inflammatory bowel disease. A promising development in the field of microbiologic diagnosis is the possibility to identify specific pathogens using the detection of bacterial or viral DNA in stool samples [Grimes et al. 2008; Zlateva et al. 2005]. Such methods are still reserved for research purposes but may be adopted in the clinical setting in following years.

Treatment options

Symptomatic therapy

Loperamide, a synthetic opioid, has been approved by the American FDA for use in adults and children older than 2 years, and is the antimotility agent of choice. It appears to be safe in most types of diarrhea, although its use is not recommended when there is gross blood in the stool or a temperature >38.5°C [Hill et al. 2006]. In patients with TD, the efficacy of loperamide alone or as an adjunct to antibiotherapy [Riddle et al. 2008] is well established. The recommended dosages are a loading dose of 4 mg orally, and then 2 mg after each loose stool, until a maximum of 16mg per day is reached in adults. The use of loperamide is not recommended in pregnant or lactating women (pregnancy risk category C, risk cannot be ruled out). Loperamide is generally well tolerated but may cause constipation, sometimes with abdominal distension and discomfort.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics have clearly demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the duration and severity of TD, at the price of side effects [Unauthored 2008; De Bruyn et al. 2000; Hill et al. 2006]. The recommended agents and dosages are summarized in Table 1. The need to balance the advantages and drawbacks of antibiotic treatment when choosing patients who will really benefit from therapy has been stressed by some commentators, who advocate avoiding unnecessary exposure to antibiotics in patients whose disease would spontaneously resolve anyway [Genton and D'Acremont, 2007].

Table 1.

Recommended antibiotics for the treatment of traveler's diarrhea. Modified from Hill et al. [2006].

| Agent | Dosage |

| Fluoroquinolones | |

| Norfloxacin | 400 mg p.o. b.i.d. |

| Ciprofloxacin | 500 mg p.o. b.i.d. |

| Ofloxacin | 200 mg p.o. b.i.d. |

| Levofloxacin | 500 mg p.o. q.d. |

| Azithromycin | 1000mg p.o. o.d. |

| Rifaximin | 200 mg p.o. t.i.d. |

Fluoroquinolones are predictably active for empirical therapy in most parts of the world and remain the drugs of first choice. However, important levels of fluoroquinolone resistance progressively develop worldwide over time, reaching 58% for the 1999—2003 period [Ruiz et al. 2007], with the edge of quinolone resistance progressing in Southeast Asia, where 93% of Campylobacter isolates were found to be ciprofloxacin-resistant [Tribble et al. 2007]. Fluoroquinolones are not recommended in pregnant or lactating women (pregnancy risk category C, risk cannot be ruled out) and in children < 18 years of age. Their most frequent side effects are gastrointestinal (anorexia, nausea, vomiting and abdominal discomfort), followed in frequency by central nervous system reactions (mild headache, dizziness, insomnia and alterations of mood). Tendinitis, QT prolongation and increases in transaminases may rarely occur.

Azithromycin, a macrolide effective against Campylobacter species as well as against most bacterial pathogens that cause TD worldwide, is recommended as a drug of choice for the treatment of TD from any part of the world [Hill et al. 2006]. Azithromycin is safe for use in children and pregnant women (pregnancy risk category B, no evidence of risk in humans). Its most frequent side effects are gastrointestinal (chiefly mild nausea), followed by pruritus, rash and an increased risk of vaginitis.

Rifaximin, an oral nonabsorbed antibiotic derived from rifampin, has been approved for the treatment of TD caused by noninvasive E. coli in travelers > 12 years old. In clinical studies, its efficacy has been similar to that of ciprofloxacin, with less unwanted effects [Dupont et al. 2007]. However, rifaximin must not be used for TD associated with fever of blood in the stool, or in TD likely to be caused by Campylocater jejuni. Rifaximin must not be used during pregnancy (pregnancy risk category C, risk cannot be ruled out) and in lactating women. Rifaximin has virtually no unwanted effects.

Conduct of therapy

Clinical features are poor predictors of the infective organism [Svenungsson et al. 2000], and obtaining stool cultures is unnecessary in most cases, so that therapy must usually be chosen empirically. Considering the benign course of TD, therapeutic abstention or symptomatic treatment may be chosen for mild cases. Fluid replacement with alternating salt and sugar solutions or oral rehydration solutions is, however, indicated in most cases. Antimicrobials can be reserved for more severe cases of classical TD, particularly when fever or bloody stools are present [Al-Abri et al. 2005]. In several head-to-head comparisons, single-dose therapy has been shown to have an efficacy equivalent to that of the more classical 3-day course of antibiotics [Ericsson et al. 2001, 1997, 1990]. In the absence of firm data on the subject, it is reasonable to choose a single-dose course of antibiotics in patients with moderate symptoms and no fever or blood in the stool, and to reserve 3-day therapy regimens for more severe cases. No specific treatment option has been tested for virus-associated cases of TD.

Persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler

Persistence of diarrhea after acute TD is infrequent: in two large studies of TD, less than 2% of patients with TD went on to chronic diarrhea lasting more than a month [Addiss et al. 1990; Steffen et al. 1987]. Whereas persistent TD was traditionally considered as pertaining to infectious causes [Dupont and Capsuto, 1996], two other disease categories account for a growing number of recognized cases: postinfectious processes, and unveiling of an underlying chronic condition.

Intestinal infections

The principal infectious causes of persistent TD are mentioned in Table 2. Cases of persistent diarrhea have been described in association with most bacteria responsible for TD (Escherichia coli, Shigella, Campylobacter, Aeromonas hydrophila). In current practice however, bacteria rarely account for diarrhea lasting for more than 2 weeks, with the notable exception of postantibiotic Clostridium difficile colitis, which may follow a common case of antibiotic-treated TD [Norman et al. 2008] and persist for several weeks.

Table 2.

Principal enteric pathogens associated with infectious causes of persistent traveler's diarrhea. In each column, names are printed in decreasing order of frequency.

| Bacteria | Protozoa | Helminths |

| Clostridium difficile Camplylobacter jejuni Salmonella spp Shigella spp Aeromonas hydrophila Mycobacteria |

Giardia lamblia Entamoeba histolytica Cryptosporidium parvum Cydospora cayetanensis Histoplasma capsulatum Leishmania donovani |

Ascaris lumbricoides Enterobius vermicularis Strongyloides stercoralis |

The most frequent infectious causes of persistent TD are represented by protozoa infections [Goodgame, 2003; Okhuysen, 2001], mostly Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum, and an ‘emerging’ protozoa, Cyclospora cayetanensis [Herwaldt, 2000; Ortega et al. 1993]. Isospora belli and Cryptosporidium parvum have been occasionally reported but are rare in immunocompe-tent patients.

The diagnosis of intestinal giardiasis traditionally relied on the stool ‘ova and parasites’ (O&P) microscopic examination; that is, the direct observation of cysts or trophozoites in three separate fresh stool samples. However, this method tends to be superseded by various immunoassays, some of which are enzyme-linked, that compare favorably with the stool O&P examination in terms of sensitivity and specificity [Aziz et al. 2001]. The diagnosis of giardiasis by detection of trophozoites and cysts in duodenal biopsies is more invasive, and unnecessary in many cases. Small bowel biopsies of patients with giardiasis can reveal a range of pathologic findings, but usually no histopathologic abnormalities are identified [Oberhuber et al. 1997]. The recommended treatment for giardiasis is oral metronidazole 250 p.o. t.i.d. for 5 days, or tinidazole 2 g in a unique dose [Gardner and Hill, 2001].

Amoebae (Entamoeba histolytica) are a classical cause of long-lasting colitis acquired in tropical areas, typically associated with a dysenteric syndrome (voiding of mucus and blood with little or no stool, abdominal pain, rectal syndrome). However, the general medical judgment regarding intestinal amebiasis has markedly changed since newer diagnostic tests have allowed to distinguish easily truly pathogenic amoebae (Entamoeba histolytica) from nonpathogenic amoebae (Entamoeba dispar and Entamoeba mosh-kovskit), which are undistinguishable by visual microscopy. Whereas the reality of ‘true’ amoebic colitis is undisputed, it is likely that many cases of unrelated digestive symptoms have been falsely attributed to amebiasis in the past, on the basis of nonpathogenic amoebae having been found in the stool. Commentators have seriously challenged the notion that any clinical picture of non-dysenteric colitis could really be attributed to amebiasis at all [Anand et al. 1997]. It is likely that the true frequency of amebiasis as an etiology for persistent TD has been overestimated.

Direct examination of stool has a relatively poor sensitivity for the diagnosis of intestinal amebiasis and does not allow for distinction between pathogenic and nonpathogenic amoebae. Antigen stool test has demonstrated a good sensitivity for the presence of amoebae and allows to tell apart the various types [Haque et al. 1998]. Although probably less sensitive than stool antigen testing, serology may be useful for diagnosing of amebiasis. Infection with Entamoeba histolytica results in the development of antibodies, while digestive colonization by Entamoeba dispar infection does not. Antibodies will usually be detectable within 5—7 days of acute infection and may persist for years. The treatment of invasive amoebic colitis relies on metronidazole (500—750 mg p.o. t.i.d. for 7—10 days), which offers a cure rate of approximately 90% [Li and Stanley, 1996].

Intestinal helminths (chiefly Ascaris, Enterobius and Strongyloides) are rare causes of diarrhea [MacPherson, 1999]. Rare cases of persistent TD have been described in association with intestinal tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria, leischmaniasis and intestinal histoplasmosis [Goulet et al. 2005]. Tropical sprue, a condition of uncertain origin associated with diarrhea, malabsorption and variable duodenal villous atrophy [Lo et al. 2007; Walker, 2003], is usually observed in residents of tropical areas but has been rarely described in returning travelers [Macaigne et al. 2004].

Postinfectious processes

These follow an episode of infectious diarrhea but are not caused by the persistence of micro-biologic agents in the digestive system. Temporary lactose malabsorption directly results from damage to the intestinal mucosa and is a frequent consequence of bacterial or viral gastroenteritis. The ingestion of lactose in subjects without lactase activity may cause abdominal bloating and, less frequently, diarrhea [Beyerlein et al. 2008]. However, the problem should not last more than a few days after resolution of the initial diarrhea. When evaluating patients with suspected symptomatic lactose malabsorption, clinicians should carefully review the relationship between the alleged symptoms and the amounts of ingested lactose. Indeed, the physiologic threshold of ingestion for the appearance of lactose-related symptoms is over 240 ml of cow's milk (or 12 g of lactose — cow's milk contains 5% lactose) in subjects with complete alactasia, as has been demonstrated in a blinded, crossover study [Suarez et al. 1995]. Thus, in otherwise normal adults (i.e. without gastrectomy or conditions associated with shortening of the bowel), symptoms appearing after the ingestion of smaller amounts of milk are probably unrelated to lactose malabsorption.

Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS)

The fact that functional bowel disorder occasionally supervenes on an episode of acute, infectious diarrhea has been known for decades [Chaudhary and Truelove, 1962] and has received substantial documentation in recent years [Dupont, 2008; Thabane et al. 2007]. The data collected so far suggest that PI-IBS is relatively common, and probably accounts for most cases of persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler [Connor, 2005]. The reported incidence of PI-IBS following an enteric infection is 4—32%, with typical irritable bowel syndrome according to the Rome III criteria being the predominant observed form. PI-IBS may follow acute diarrhea caused by bacteria as well as viruses [Marshall et al. 2007], protozoa [Dizdar et al. 2007] and helminths [Soyturk et al. 2007], and has been reported after TD [Stermer et al. 2006; Okhuysen et al. 2004; Ilnyckyj et al. 2003]. Risk factors for the appearance of PI-IBS have been recently reviewed [Spiller and Garsed, 2009] and include the duration of the initial illness, tobacco smoking, female sex, depression, hypo-chondriasis and adverse life events in the preceding 3 months. No clear-cut risk factor pertaining to the infectious agent has been consistently found. In one retrospective study, the risk of PI-IBS after Campylobacter jejuni infections was significantly higher than that associated with Salmonella spp. [Neal et al. 1997]. Standard biologic, endoscopic and histologic studies are normal in patients with PI-IBS, as they are in patients with IBS. However, the pathogenesis PI-IBS may involve a ‘micro-inflammatory’ process, since several subtle inflammatory abnormalities have been demonstrated in the digestive mucosa of patients with PI-IBS, namely an increased number of lymphocytes and serotonin-producing enterochromaffin cells [Dunlop et al. 2003; Spiller et al. 2000], IL-1b [Gwee et al. 2003] and an increased intestinal permeability [Marshall et al. 2004]. Furthermore, visceral hypersensitivity and abnormalities of serotonin metabolism have been demonstrated in animal model of PI-IBS [Keating et al. 2008; Bercik et al. 2004]. So far, no specific prevention and therapy for PI-IBS are available and its management is similar to that of ‘sporadic’ IBS [Dalrymple and Bullock, 2008; Spiller et al. 2007]. Of particular interest is the efficacy of pro-biotics to treat symptoms of sporadic IBS, as has been recently demonstrated in two well-designed randomized controlled trials of Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 [Brenner et al. 2009; Whorwell et al. 2006; O'Mahony et al. 2005].

Unveiling of a chronic condition

Not infrequently, an apparently unrelated chronic condition causing diarrhea appears in the aftermath of an acute gastroenteritis, a typical example of which is the discovery of celiac disease during the work-up of a case of persistent TD [Landzberg et al. 2005]. Whether true causality or mere coincidence is at work in such cases is uncertain. In most cases, the true nature of the association between the two diseases pertains to the common medical circumstance that preclinical, silent diseases often become apparent after the affected organ is submitted to some kind of stress. The management of unexplained, persistent diarrhea in a returning traveler should include a basic diagnostic work-up directed at the causes of chronic diarrhea, a matter that has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [Schiller, 2004]. A special mention, however, is deserved by the case of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Indeed, the finding of overt IBD supervening on a case of acute, infectious diarrhea is classical, and this phenomenon has been substantiated in retrospective studies [Porter et al. 2008; Garcia Rodriguez et al. 2006]. The existence and potential nature of a causal relationship between the acute infection and the IBD in such cases is uncertain [Irving and Gibson, 2008]. Finally, rare occurrences of factitious digestive parasitosis linked to psychiatric conditions, such as the Munchhausen syndrome, have been described in returning travelers [Gill and Hamer, 2002].

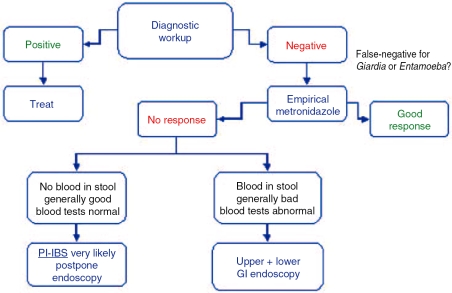

Figure 1.

Basic management algorithm for patients with persistent traveler's diarrhea. See text for the details of the diagnostic work-up. PI-IBS, post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome.

Practical approach

In addition to a detailed history and physical examination, patients with persistent TD should receive a basic diagnostic work-up comprising blood tests and a stool examination. The blood tests should explore the possibility of anemia, eosinophilia, systemic inflammation, basic nutritional deficiencies, hyperthyroidism, and the presence IgA antibodies directed against tissue transglutaminase (which are diagnostic of celiac disease) [De Saussure et al. 2005]. The stool tests should assess the presence of classical bacterial pathogens and Clostridium difficile toxin A, and should include O&P on three separate fresh stool samples. If available locally, immunologic testing for Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica antigens in a stool sample is advisable.

A proposed management algorithm is presented in Figure 1. If the initial diagnostic work-up is negative, a false-negative test for Giardia or Entamoeba cannot be excluded, and a course of metronidazole is recommended (500mg p.o. t.i.d. for 7 days). If symptoms persist in a generally well patient who had no visible blood in the stool and devoid of any significant laboratory abnormality, the diagnosis of PI-IBS is very likely and further diagnostic studies may be postponed. On the contrary, the next diagnostic step should comprise upper and lower digestive endoscopic studies with biopsies of all the explored segments.

Conclusion

The high attack rate and incapacitation potential of acute TD are in sharp contrast with its almost universally benign course. Antibiotherapy is chosen empirically and is highly effective, but the magnitude of its clinical benefit is disputed, and its use should be restricted to the more severe forms of acute TD. Persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler represents a challenging situation, in which the clinician must identify patients suffering from various persistent infections or unrelated chronic diarrheal diseases, among a majority of subjects presenting with postinfec-tious functional bowel disorders.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- Adachi J.A., Jiang Z.D., Mathewson J.J., Verenkar M.P., Thompson S., Martinez-Sandoval F.et al. (2001)Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli as a major etiologic agent in traveler's diarrhea in 3 regions of the world. Clin Infect Dis 32:1706–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addiss D.G., Tauxe R.V., Bernard K.W.(1990)Chronic diarrhoeal illness in US peace corps volunteers. Int J Epidemiol 19:217–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abri S.S., Beeching N.J., Nye F.J.(2005)Traveller's diarrhoea. Lancet Infect Dis 5:349–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A.C., Reddy P.S., Saiprasad G.S., Kher S.K.(1997)Does non-dysenteric intestinal amoebiasis exist? Lancet 349:89–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansdell V.E., Ericsson CD.(1999)Prevention and empiric treatment of traveler's diarrhea. Med Clin North Am 83:945–973, vi [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz H., Beck C.E., Lux M.F., Hudson M.J.(2001)A comparison study of different methods used in the detection of Giardia lamblia. Clin Lab Sci 14:150–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercik P., Wang L., Verdu E.F., Mao Y.K., Blennerhassett P., Khan W.I.et al. (2004)Visceral hyperalgesia and intestinal dysmotility in a mouse model of postinfective gut dysfunction. Gastroenterology 127:179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyerlein L., Pohl D., Delco F., Stutz B., Fried M., Tutuian R.(2008)Correlation between symptoms developed after the oral ingestion of 50 g lactose and results of hydrogen breath testing for lactose intolerance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27:659–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner D.M., Moeller M.J., Chey WD., Schoenfeld P.S.(2009)The utility of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 104:1033–1049,quiz 1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin A.R., Carpenter CM., Dudley WC, Gibson L.C, Pratdesaba R., Torres O.et al. (2005)Prevalence of norovirus among visitors from the United States to Mexico and Guatemala who experience traveler's diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol 43:1112–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary N.A., Truelove S.C.(1962)The irritable colon syndrome. a study of the clinical features, predisposing causes, and prognosis in 130 cases. QJ Med 31:307–322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor B.A.(2005)Sequelae of traveler's diarrhea: focus on postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 41(Suppl 8):S577–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple J., Bullock I.(2008)Diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 336:556–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruyn G., Hahn S., Borwick A.(2000)Antibiotic treatment for travellers' diarrhoea.Cochrane Database Syst Rev:CD002242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- De Saussure P., Joly F., Bouhnik Y.(2005)Contribution of autoantibody assays to the diagnosis of adulthood celiac disease. Joint Bone Spine 72:279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizdar V., Gilja O.H., Hausken T.(2007)Increased visceral sensitivity in giardia-induced post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Effect of the 5HT3-antagonist ondanse-tron. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19:977–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop S.P., Jenkins D., Neal K.R., Spiller R.C.(2003)Relative importance of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia, anxiety, and depression in postinfectious IBS. Gastroenterology 125:1651–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont A.W.(2008)Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 46:594–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H.L., Capsuto E.G.(1996)Persistent diarrhea in travelers. Clin Infect Dis 22:124–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H.L., Jiang Z.D., Belkind-Gerson J., Okhuysen P.C., Ericsson CD., Ke S.et al. (2007)Treatment of travelers' diarrhea: randomized trial comparing rifaximin, rifaximin plus loperamide, and loperamide alone. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson CD., Dupont H.L., Mathewson J.J.(1997)Single dose ofloxacin plus loperamide compared with single dose or three days of ofloxacin in the treatment of traveler's diarrhea. J Travel Med 4:3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson CD., Dupont H.L., Mathewson J.J.(2001)Optimal dosing of ofloxacin with loperamide in the treatment of non-dysenteric travelers' diarrhea. J Travel Med 8:207–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson CD., Dupont H.L., Mathewson J.J., West M.S., Johnson P.C., Bitsura J.A.(1990)Treatment of traveler's diarrhea with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim and loperamide. JAMA 263:257–261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Rodriguez L.A., Ruigomez A., Panes J.(2006)Acute gastroenteritis is followed by an increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 130:1588–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner T.B., Hill D.R.(2001)Treatment of giardiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 14:114–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genton B., D'Acremont V.(2007)Evidence of efficacy is not enough to develop recommendations: antibiotics for treatment of traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 44:1520;author reply 1521-1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill C.J., Hamer D.H.(2002)‘Doc, there's a worm in my stool’: Munchausen parasitosis in a returning traveler. J Travel Med 9:330–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodgame R.(2003)Emerging causes of traveler's diarrhea: cryptosporidium, cyclospora, isospora, and microsporidia. Curr Infect Dis Rep 5:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulet C.J., Moseley R.H., Tonnerre C, Sandhu I.S., Saint S.(2005)Clinical problem-solving. the unturned stone. N EnglJ Med 352:489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood Z., Black J., Weld L., O'Brien D., Leder K., Von Sonnenburg F.et al. (2008)Gastrointestinal infection among international travelers globally. J Travel Med 15:221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes K.A., Mohamed J.A., Dupont H.L., Padda R.S., Jiang Z.D., Flores J.et al. (2008)PCR-based assay using occult blood detection cards for detection of diarrheagenic escherichia coli in specimens from U. S. travelers to Mexico with acute diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol 46:2227–2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwee K.A., Collins S.M., Read N.W., Rajnakova A., Deng Y., Graham J.C.et al. (2003)Increased rectal mucosal expression of interleukin 1beta in recently acquired post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 52:523–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque R., Ali I.K., Akther S., Petri W.A., Jr(1998)Comparison of PCR, isoenzyme analysis, and antigen detection for diagnosis of entamoeba histoly-tica infection. J Clin Microbiol 36:449–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwaldt B.L.(2000)Cyclospora cayetanensis: a review, focusing on the outbreaks of cyclosporiasis in the 1990s. Clin Infect Dis 31:1040–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D.R.(2000)Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of americans traveling to developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg 62:585–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D.R., Ericsson CD., Pearson R.D., Keystone J.S., Freedman D.O., Kozarsky P.E.et al. (2006)The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 43:1499–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilnyckyj A., Balachandra B., Elliott L., Choudhri S., Duerksen D.R.(2003)Post-traveler's diarrhea irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 98:596–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving P.M., Gibson P.R.(2008)Infections and IBD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z.D., Lowe B., Verenkar M.P., Ashley D., Steffen R., Tornieporth N.et al. (2002)Prevalence of enteric pathogens among international travelers with diarrhea acquired in Kenya (Mombasa), India (Goa), or Jamaica (Montego Bay). J Infect Dis 185:497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.F., Bulens S.N., Gettner S., Garman R.L., Vugia D.J., Blythe D.et al. (2004)Use of stool collection kits delivered to patients can improve confirmation of etiology in foodborne disease outbreaks. Clin Infect Dis 39:1454–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating C, Beyak M., Foley S., Singh G., Marsden C, Spiller R.et al. (2008)Afferent hypersensitivity in a mouse model of post-inflammatory gut dysfunction: role of altered serotonin metabolism. J Physiol 586:4517–4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko G., Garcia C., Jiang Z.D., Okhuysen P.C., Belkind-Gerson J., Glass R.I.et al. (2005)Noroviruses as a cause of traveler's diarrhea among students from the United States visiting Mexico. J Clin Microbiol 43:6126–6129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landzberg B.R., Connor B.A.(2005)Persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler: think beyond persistent infection. Scand J Gastroenterol 40:112–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E., Stanley S.L., Jr(1996)Protozoa. Amebiasis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 25:471–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo A., Guelrud M., Essenfeld H., Bonis P.(2007)Classification of villous atrophy with enhanced magnification endoscopy in patients with celiac disease and tropical sprue. Gastrointest Endosc 66:377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaigne G., Boivin J.F., Auriault M.L., Deplus R.(2004)Tropical sprue: two cases in the Paris area. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 28:913–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson D.W.(1999)Intestinal parasites in returned travelers. Med Clin North Am 83:1053–1075 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.K., Thabane M., Borgaonkar M.R., James C.(2007)Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome after a food-borne outbreak of acute gastroenteritis attributed to a viral pathogen. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:457–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.K, Thabane M., Garg A.X., Clark W, Meddings J., Collins S.M.(2004)Intestinal permeability in patients with irritable bowel syndrome after a waterborne outbreak of acute gastroenteritis in Walkerton, Ontario. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 20:1317–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meraz I.M., Jiang Z.D., Ericsson CD., Bourgeois A.L., Steffen R., Taylor D.N.et al. (2008)Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and diffusely adherent E. coli as likely causes of a proportion of pathogen-negative travelers' diarrhea - a PCR-based study. J Travel Med 15:412–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal K.R., Hebden J., Spiller R.(1997)Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. BMJ 314:779–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman F.F., Perez-Molina J., Perez De Ayala A., Jimenez B.C., Navarro M., Lopez-Velez R.(2008)Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea after antibiotic treatment for traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 46:1060–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Mahony L., McCarthy J., Kelly P., Hurley G., Luo F., Chen K.et al. (2005)Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology 128:541–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberhuber G., Kastner N, Stolte M.(1997)Giardiasis: a histologic analysis of 567 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol 32:48–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okhuysen P.C.(2001)Traveler's diarrhea due to intestinal protozoa. Clin Infect Dis 33:110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okhuysen P.C., Jiang Z.D., Carlin L., Forbes C., Dupont H.L.(2004)Post-diarrhea chronic intestinal symptoms and irritable bowel syndrome in North American Travelers to Mexico. Am J Gastroenterol 99:1774–1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Y.R., Sterling C.R., Gilman R.H., Cama V.A., Diaz F.(1993)Cyclospora species - a new protozoan pathogen of humans. N Engl J Med 328:1308–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter C.K., Tribble D.R., Aliaga P.A., Halvorson H.A., Riddle M.S.(2008)Infectious gastroenteritis and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 135:781–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle M.S., Arnold S., Tribble D.R.(2008)Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in traveler's diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 47:1007–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J., Marco F., Oliveira I., Vila J., Gascon J.(2007)Trends in antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter spp. causing traveler's diarrhea. Apmis 115:218–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salam I., Katelaris P., Leigh-Smith S., Farthing M.J.(1994)Randomised trial of single-dose ciprofloxacin for travellers' diarrhoea. Lancet 344:1537–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller L.R.(2004)Chronic diarrhea. Gastroenterology 127:287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyturk M., Akpinar H., Gurler O., Pozio E., Sari I., Akar S.et al. (2007)Irritable bowel syndrome in persons who acquired trichinellosis. AmJ Gastroenterol 102:1064–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller R., Aziz Q., Creed F., Emmanuel A., Houghton L., Hungin P.et al. (2007)Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut 56:1770–1798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller R., Garsed K.(2009)Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 136:1979–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller R.C., Jenkins D., Thornley J.P., Hebden J.M., Wright T, Skinner M.et al. (2000)Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute Campylobacter enteritis and in post-dysenteric irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 47:804–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R.(2005)Epidemiology of traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 41(Suppl. 8):S536–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R., Rickenbach M., Wilhelm U., Helminger A., Schar M.(1987)Health problems after travel to developing countries. J Infect Dis 156:84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R., Tornieporth N., Clemens S.A., Chatterjee S., Cavalcanti A.M., Collard F.et al. (2004)Epidemiology of travelers' diarrhea: details of a global survey. J Travel Med 11:231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stermer E., Lubezky A., Potasman I., Paster E., Lavy A.(2006)Is traveler's diarrhea a significant risk factor for the development of irritable bowel syndrome? A prospective study. Clin Infect Dis 43:898–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez F.L., Savaiano D.A., Levitt M.D.(1995)A comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intolerance. N Engl J Med 333:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenungsson B., Lagergren A., Ekwall E., Evengard B., Hedlund K.O., Karnell A.et al. (2000)Enteropathogens in adult patients with diarrhea and healthy control subjects: a 1-year prospective study in a Swedish clinic for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 30:770–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabane M., Kottachchi D.T., Marshall J.K.(2007)Systematic review and meta-analysis: the incidence and prognosis of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 26:535–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribble D.R., Sanders J.W, Pang L.W, Mason C, Pitarangsi C, Baqar S.et al. (2007)Traveler's diarrhea in Thailand: randomized, double-blind trial comparing single-dose and 3-day azithromycin-based regimens with a 3-day levofloxacin regimen. Clin Infect Dis 44:338–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unauthored.(2008)Drugs for traveler's diarrhea.Med Lett Drugs Ther50:58–59 [PubMed]

- Vargas M., Gascon J., Gallardo F., De Jimenez Anta M.T., Vila J.(1998)Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains detected by PCR in patients with travelers' diarrhea. Clin Microbiol Infect 4:682–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Sonnenburg F., Tornieporth N., Waiyaki P., Lowe B., Peruski L.F., Jr, Dupont H.L.et al. (2000)Risk and aetiology of diarrhoea at various tourist destinations. Lancet 356:133–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M.M.(2003)What is tropical sprue? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 18:887–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whorwell P.J., Altringer L., Morel J., Bond Y., Charbonneau D., O'Mahony L.et al. (2006)Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 101:1581–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlateva K.T., Maes P., Rahman M., Van Ranst M.(2005)Chromatography paper strip sampling of enteric adenoviruses type 40 and 41 positive stool specimens. Virol J 2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]