Abstract

The development of diagnostic criteria has enabled greater recognition of menstrual migraine as a highly prevalent and disabling condition meriting specific treatment. Although few therapeutic trials have yet been undertaken in accordance with the criteria, the results of those published to date confirm the efficacy of acute migraine drugs for symptomatic treatment. If this approach is insufficient, the predictability of attacks provides the opportunity for perimenstrual prophylaxis. Continuous contraceptive strategies provide an additional option for management, although clinical trial data are limited. Future approaches to treatment could explore the genomic and nongenomic actions of sex steroids.

Keywords: menstrual migraine, therapy, perimenstrual prophylaxis

Incidence and prevalence of menstrual migraine

Four of every ten women and two of every ten men will contract migraine in their lifetime, most before age 35 years [Stewart et al. 2008]. More than 50% of women with migraine, both in the general population and presenting to specialist clinics, report an association between migraine and menstruation [MacGregor et al. 2004, 1997, 1990; Couturier et al. 2003; Dzoljic et al. 2002; Granella et al. 1993].

The peak incidence of migraine during the menstrual cycle occurs on the days directly before and after the first day of menstruation [MacGregor and Hackshaw, 2004; Dzoljic et al. 2002; Stewart et al. 2000; Johannes et al. 1995]. In a population-based study, Stewart et al. [2000] noted a significantly elevated risk of migraine without aura on the first two days of menstruation [odds ratio (OR) 2.04; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.49–2.81]. The lowest risk for headache was around the expected time of ovulation [OR 0.44; 95% CI 0.27–0.72]. Headache duration appeared to be significantly longer for migraine headaches in the 3 to 7 day period before onset of menses [Stewart et al. 2000]. In a clinic-based study, MacGregor and Hackshaw [2004] noted that women were 25% (RR 1.25) more likely to have migraine in the five days leading up to menstruation increasing to 71% (RR 1.71; 95% CI 1.45–2.01 p<0.0001) in the two days before menstruation. The risk of migraine was highest on the first day of menstruation and the following two days (RR 2.50; 95% CI 2.24–2.77 p<0.0001). Similarly, in a population-based study, Wciber et al. [2007] found the highest risk of migraine on the first three days of menses (HR 1.96; p<0.00001). Menstrual migraine is also associated with increased menstrual distress and disability [Dowson et al. 2005; Kibler et al. 2005; Granella et al. 2004; MacGregor et al. 2004; Couturier et al. 2003; Beckham et al. 1992]. As a consequence of these findings, the International Headache Society developed diagnostic criteria for menstrual migraine (Box 1).

Box 1. Diagnostic criteria for pure menstrual migraine and menstrually-related migraine [adapted from Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (IHS), 2004]. The first day of menstruation is day 1 and the preceding day is day -1; there is no day 0. Forthe purposes of this classification, menstruation is considered to be endometrial bleeding resulting from either the normal menstrual cycle or from the withdrawal of exogenous progestogens, as in the case of combined oral contraceptives and cyclical hormone replacement therapy.

Pure menstrual migraine

Attacks, in a menstruating woman, fulfilling criteria for migraine without aura

Attacks occur exclusively on day 1 ±2 (i.e. days —2 to +3) of menstruation in at least two out of three menstrual cycles and at no other times of the cycle

Menstrually-related migraine

Attacks, in a menstruating woman, fulfilling criteria for migraine without aura

Attacks occur on day 1 ±2 (i.e. days —2 to +3) of menstruation in at least two out of three menstrual cycles and additionally at other times of the cycle

For most women with menstrual attacks, migraine also occurs at other times of the month ('menstrually-related’ migraine) [Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (IHS), 2004; MacGregor et al. 1990]. Fewer than 10% of women report migraine exclusively with menstruation and at no other time of the month ('pure’ menstrual migraine) [Headache Classification Subcommittee of the IHS, 2004; MacGregor et al. 2004; Dzoljic et al. 2002; Granella et al. 1993; MacGregor et al. 1990]. To confirm a diagnosis contemporaneous diary cards covering a minimum of three menstrual cycles should be reviewed.

Acute treatment

Acute treatment of menstrual migraine is the same as for nonmenstrual attacks and includes a combination of analgesics with or without prokinetic antiemetics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ergot derivatives and triptans [Steiner et al. 2007]. The nonprescription combination of acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine (AAC; Excedrin Migraine, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, New York) was assessed for the treatment of menstruation-associated migraine compared with migraine not associated with menses using data from three double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-dose trials [Silberstein et al. 1999]. Subjects with severe vomiting or disability were excluded. Menstruation-associated migraine was treated by 185 women and 781 women treated migraine not associated with menses. There was no statistically significant difference in pain response between menstruation-associated migraine and migraine not associated with menses.

Sumatriptan for the acute treatment of migraine occurring between day —2 and day +4 of the cycle was evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study [Nett et al. 2003]. A single headache was treated with oral sumatriptan 50 mg, sumatriptan 100 mg, or placebo taken within 1 hour of onset of a mild headache. At 2 hours, 51% and 61% of the sumatriptan 50 mg and 100 mg groups were pain-free compared with 29% of the placebo group (p<0.001). Sustained pain-free response from 2 to 24 hours was reported by 30% of the sumatriptan 50 mg group (p = 0.007), 31% of the sumatriptan 100 mg group (p = 0.004), and 14% of the placebo group.

A prospective, multicentre, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, two-group crossover study was carried out on patients who self-reported migraine during an 8 day window starting 3 days before the onset of menstruation in two of their last three menstrual cycles with >80% of their attacks falling within the window in the previous 6 months [Dowson et al. 2005]. Women treated all migraine attacks for 2 months with sumatriptan 100 mg and for 2 months with placebo. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients reporting headache relief at 4 hours for the first treated attack. Significantly more women receiving sumatriptan than placebo reported headache relief for attacks occurring inside (67% versus 33%, p = 0.007) and outside (79% versus 31%, p< 0.001) the menstrual period.

In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of acute treatment of migraine occurring between day —3 and day +5 of the menstrual cycle zolmitriptan 1.25 mg was used for mild pain, 2.5 mg for moderate pain, and 5 mg for severe headache pain [Loder et al. 2004]. Zolmitriptan (all doses) significantly increased 2-hour headache response compared with placebo (48% versus 27%, respectively; p<0.0001). Pain relief was statistically superior (p = 0.03) with zolmitriptan treatment, as early as 30 minutes after dosing.

Naratriptan for the acute treatment of migraine occurring on day —2 to day +4 of the menstrual cycle was assessed in a randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial [Massiou et al. 2005]. A significantly greater percentage of the naratriptan group were pain free at 4 hours compared with placebo (58% versus 30% with placebo; p<0.001).

Almotriptan and zolmitriptan for acute treatment of menstrual migraine were evaluated in a double-blind, randomized trial of 255 women [Allais et al. 2006]. Pain-free response at 2 hours was achieved in 44.9% of patients receiving almotriptan and 41.2% of those receiving zolmitriptan. The 2-hour pain-free status was sustained for at least 24 hours in 29.3% and 27.1% of patients treated with almotriptan and zolmitriptan, respectively. In a post hoc analysis of the AXERT Early miGraine Intervention Study (AEGIS), 275 women treated 506 migraine attacks. Almotriptan treatment efficacy outcomes were not significantly different for menstrual and nonmenstrual attacks: 2-hour pain relief, 77.4% versus 68.3%; 2-hour pain free, 35.4% versus 35.9%; and sustained pain free, 22.9% versus 23.8% [Diamond et al. 2008].

Rizatriptan 10 mg was effective for the treatment of ICHD-II menstrual migraine in two prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, as measured by 2 hour pain relief and 24 hour sustained pain relief in 707 women [Nett et al. 2008]. In an early intervention model using rizatriptan 10 mg, 2 hour pain-free rates were comparable for 94 women treating menstrual and nonmenstrual migraine attacks [Martin et al. 2008].

Perimenstrual prophylaxis

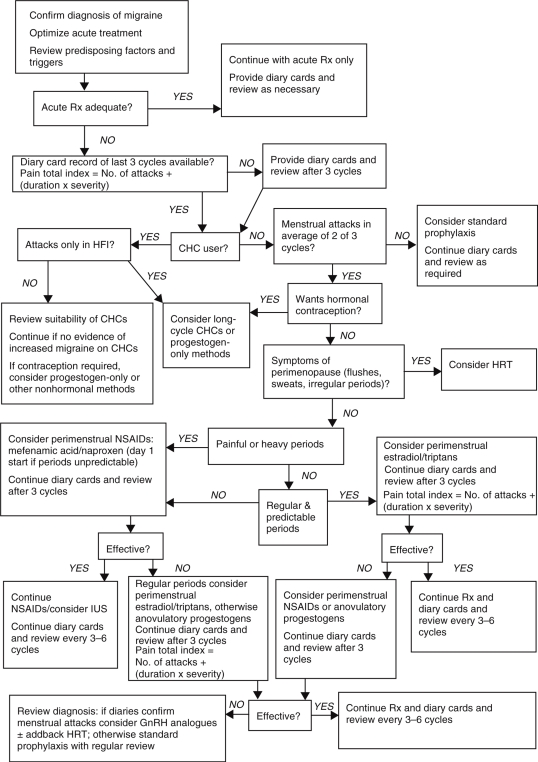

When acute therapy is insufficient to reduce disability from menstrual migraine, there is the option for preventing attacks using perimenstrual or continuous prophylaxis. The choice depends on the individual woman's type of migraine, regularity of menstruation, other menstrual problems and need for contraception (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Management strategies for menstrual migraine. CHC, combined hormonal contraceptives; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue; HFI, hormone free interval; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; lUS, intrauterine system; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; Rx, treatment. Reproduced with permission from MacGregor, E.A. (2007) Menstrual migraine: a clinical review, J Fam Piann Reprod Health Care 33: 36–47.

Short-term prophylactic strategies have the advantage that treatment is only used at the time of need, potentially reducing the risk of adverse events compared with continuous prophylaxis. However, results from RCTs are limited (Table 1). None of the drugs and hormones recommended for perimenstrual prophylaxis are licensed for management of menstrual migraine.

Table 1.

Randomized placebo-controlled trials of perimenstrual prophylaxis.

| Trial | Study design | Sample size | Rx | No. of cycles | Treatment start | Primary endpoint | Results |

| Naproxen | |||||||

| Sances et al. [1990] | Parallel | 35 | 550 mg bd | 3 | 7 days before expected menses through 6th day of menstrual flow | Pain Total Index no. of attacks (duration X severity) | NS |

| Estradiol | |||||||

| De Lignieres et al. [1986] | Cross-over | 18 | 1.5 mg | 3 | 2 days before expected menses for 7 days | Presence of migraine | Estradiol 30.8% PCB 96.3% (p50.01) |

| Dennerstein et al. [1988] | Cross-over | 18 | 1.5mg | 4 | 2 days before expected migraine for 7 days | Days of moderate to severe migraine during treatment | Estradiol 47 days PCB 86 days (p50.001) |

| Pfaffenrath [1993] | Cross-over | 41 | 50 mcg | 4 | 2 days before expected migraine Duration not stated | Reduction in headache duration, intensity and impairment | NS |

| Smits et al. [1994] | Cross-over | 20 | 50 mcg | 3 | 2 days before expected menses for 8 days | Percentage of treatment periods with migraine | NS |

| MacGregor et al. [2006] | Cross-over | 35 | 1.5 mg | 6 | 9 days after LH surge (approx day −5/−6) until 2nd full day of menses (approx 8 days) | Reduction in migraine days during treatment | 22% RR0.78 95% CI 0.62–0.99 (p=0.04) |

| Frovatriptan | |||||||

| Silberstein et al. [2004] | Cross-over | 445 | 2.5mg bd 2.5mg od | 3 | 2 days before expected migraine for 6 days | Incidence of migraine during each treatment period | bd 43% od 52% PCB 69% (p50.0001) vs PCB |

| Brandes et al. [in press] | Parallel | 410 | 2.5mg bd 2.5mg od | 3 | 2 days before expected migraine for 6 days | No. of headache-free treatment periods | bd 0.92 od 0.69 PCB 0.42 (p50.001 and p50.02) vs PCB |

| Naratriptan | |||||||

| Newman et al. [2001] | Parallel | 206 | 1mg bd 2.5mg bd | 4 | 2 days before expected menses for 5 days | Percentage headachefree treatment periods per patient Mean no. of migraines | 1mg bd 50% PCB 25% (p=0.003) 2.0 vs 4.0 (p50.05) 2.5mg NS |

| Mannix et al. [2007] | Parallel | Study 1: 218 | 1mg bd | 4 | 3 days before expected menses for 6 days | Mean percentage of treatment periods without migraine per patient | Study 1: naratriptan 40% PCB 27% (p50.05) |

| Study 2: 273 | Study 2: naratriptan 37% PCB 24% (p50.05) | ||||||

| Zolmitriptan | |||||||

| Tuchman et al. [2008] | Parallel | 217 | 2.5mg bd 2.5mg tds | 3 | 2 days before expected menses for 7 days | ≥50% reduction in migraine | tds 58.6% bd 54.7% PCB 37.8% (p=0.0007 and p=0.002) vs PCB |

bd, twice daily; NS, not sigficant vs placebo; od, once daily; PCB, placebo; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, relative risk; tds, three times daily.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Studies using 550 mg naproxen once or twice daily perimenstrually have shown limited efficacy [Nattero et al. 1991; Sances et al. 1990; Szekely et al. 1989; Sargent et al. 1985]. A recent open-label study of perimenstrual naproxen 550 mg daily has shown efficacy for prevention of menstrual migraine [Allais et al. 2007]. NSAIDs are useful as first-line agents for migraine associated with dysmenorrhoea and/or menorrhagia.

Estradiol

Maintaining luteal phase oestrogen levels can prevent menstrual attacks [MacGregor et al. 2006; Somerville, 1975a, 1975b, 1972]. Doses equivalent to 1.5 mg estradiol gel allow a mean estradiol plasma level of 80pg/ml to be reached. Lower doses of oestrogen are not effective [Smits et al. 1994; Pradalier et al. 1994; Pfaffenrath, 1993].

There is evidence that some women responding to oestrogen supplements experience delayed attacks when the supplements are discontinued [MacGregor et al. 2006] Oestrogen ‘withdrawal’ migraine may occur if treatment is not continued until the rise in endogenous oestrogen. Although there are no trial data, clinical practice suggests that for these women the duration of supplement use can be extended until day 7 of the cycle, tapering the dose over the last 2 days.

Triptans

Trials using frovatriptan, naratriptan, sumatriptan and zolmitriptan for perimenstrual prophylaxis have suggested efficacy [Tuchman et al. 2008; Moschiano et al. 2005; Silberstein et al. 2004; Newman et al. 2001, 1998].

Perimenstrual triptan prophylaxis is well tolerated and the high completion rates in the clinical trials are notable. Post-treatment migraine has been reported following naratriptan but not frovatriptan [Mannix et al. 2007; Brandes et al. (in press)]

A small pilot, open-label, nonrandomized, parallel group study assessed the efficacy of 2.5 mg frovatriptan against 25 mg transdermal oestrogen or 50 mg naproxen sodium each taken once daily for 6 days, beginning 2 days before the expected onset of menstrual headache [Guidotti et al. 2007]. The baseline median headache severity score severity was 4.6, 4.2 and 4.3 in the group subsequently treated with frovatriptan, transdermal oestrogen and naproxen sodium, respectively (p = 0.819) compared with scores of 2.5, 3.0 and 3.0 during treatment (p = 0.049). Although these results suggest that short-term prophylaxis of menstrual migraine with frovatriptan may be more effective than transdermal oestrogen or naproxen sodium, the drug doses used in the study were suboptimal.

Continuous hormonal strategies

Combined hormonal contraceptives

Women with irregular periods or who require contraception may benefit from specific strategies that prevent migraine in the hormone-free interval of combined hormonal contraceptives, although to date evidence is currently based more on clinical practice than on robust clinical trial data [Calhoun and Ford, 2008; MacGregor, 2007].

Continuous hormones, in place of the usual regimen of 3 weeks of active followed by 1 week of inactive pills or no therapy, have been recommended based on evidence that oestrogen withdrawal provokes headache in susceptible women. Compared with the usual 21/7-day regimen of combined hormonal contraceptives, a 168-day extended placebo-free regimen led to a decrease in headache severity along with improvement in work productivity and involvement in activities [Sulak et al. 2007]. Similarly, an extended 84-day regimen of a transdermal contraceptive reduced the total incidence of mean headache days compared with a 21/7-day regimen [Laguardia et al. 2005]. No double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, or even open-label trials, of this strategy in menstrual migraine have been performed. However, there is increasing clinical experience of their use in this way [Edelman et al. 2006]. Combined hormonal contraceptives should not be used by women with migraine with aura because of the synergistic increased risk of ischaemic stroke [World Health Organization, 2004; MacGregor and Guillebaud, 1998].

Progestogen-only contraceptives

There are no studies assessing anovulatory progestogens such as the intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, subdermal etonogestrel and oral desogestrel, which inhibit ovulation. In general, standard contraceptive oral progestogens have little place in the management of menstrual migraine since most do not inhibit ovulation and are associated with a disrupted menstrual cycle [Chumnijaraki et al. 1984]. In contrast, unlicensed higher doses of oral progestogen, sufficient to inhibit ovulation, have shown benefit [Davies et al. 2003].

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues

Although effective, adverse effects of oestrogen deficiency; for example, hot flushes, restrict their use [Holdaway et al. 1991]. The hormones are also associated with a marked reduction in bone density and should not usually be used for longer than 6 months without regular monitoring and bone densitometry. ‘Add-back’ continuous combined oestrogen and progestogen can be given to counter these difficulties [Martin et al. 2003; Murray and Muse, 1997]. Given these limitations, in addition to increased cost, such treatment should be instigated only in specialist departments.

Future therapeutic approaches

The association between sex steroids and migraine warrants further investigation and has the potential to result in more targeted diagnosis and treatment. Sex steroid activity is not confined to reproductive tissues, having activity in both the peripheral and central nervous systems through genomic and nongenomic effects. Studies investigating the role of the oestrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) gene in migraine show a significant association of the A allele of the G594A SNP with migraine [Colson et al. 2004]. The progesterone receptor (PGR) PROGINS insert has also been implicated [Colson et al. 2005]. Women who carry a copy of both PR and ESR1 risk alleles were 3.2 times more likely to suffer from migraine, an effect that is greater than the independent effects of these genetic variants on disease susceptibility. It is anticipated that this association will be stronger in women with menstrual migraine, who have a strong hormonal trigger for attacks.

If the genes that play a role in this subtype of migraine can be identified, it should be possible to develop objective ways of testing for these genes as a diagnostic tool. Accurate diagnosis of menstrual migraine can aid the selection of currently available treatments. Further, identification of the genes involved could ultimately lead to the development of more effective treatments for this disabling condition, targeted to the specific genes.

Understanding how the genetics translates into a clinical outcome could also provide a more targeted therapeutic approach. Animal models suggest that abnormalities in how oestrogen modulates neuronal function in migraine are due to a mismatch between its gene-regulation and membrane effects [Welch et al. 2006]. The hypothesis is that during phases of high oestrogen levels, increased neuronal excitability is balanced by homeostatic gene regulation in brain cortex, and nociceptive systems. When oestrogen is ‘withdrawn’ around menstruation, mismatch in homeostatic gene regulation by oestrogen unmasks non-nuclear mitogen-activated hyperexcitability of cell membranes, sensitizing neurons to triggers that activate migraine attacks. At the trough of oestrogen levels, the downregulating effect on inflammatory genes is lost and peptide modulated central sensitization is increased as is pain and disability of the migraine attack.

Other potential lines of research could enable a better understanding of the interplay between oestrogen and serotonin. The mechanisms underlying the benefit of perimenstrual triptan prophylaxis are as yet unexplained. Sex steroids modulate neurotransmission in the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves, and influence receptor activity of other neurotransmitters, including the serotonergic system. Oestrogen is associated with increased production of serotonin, reduced serotonin reuptake and decreased serotonin degradation.

The role of progesterone also merits more research. Although oestrogen ‘withdrawal’ can trigger migraine in the absence of progesterone, the GABAergic actions of progestrogen are likely to modulate pain and pain perception.

Conflict of interest statement

Dr MacGregor has acted as a paid consultant to, and/or her department has received research funding from, Addex, AstraZeneca, BTG, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Merck and Pozen.

References

- Allais G., Acuto G., Cabarrocas X., Esbri R., Benedetto C., Bussone G. (2006) Efficacy and tolerability of almotriptan versus zolmitriptan for the acute treatment of menstrual migraine. Neurol Sci 27(Suppl. 2): S193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allais G., Bussone G., De Lorenzo C., Castagnoli Gabellari I., Zonca M., Mana O.et al. (2007) Naproxen sodium in short-term prophylaxis of pure menstrual migraine: pathophysiological and clinical considerations. Neurol Sci 28(Suppl. 2): S225–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham J.C., Krug L.M., Penzien D.B., Johnson C.A., Mosley T.H., Meeks G.R.et al. (1992) The relationship of ovarian steroids, headache activity and menstrual distress: a pilot study with female migraineurs. Headache 32: 292–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes J.L., Poole A.C., Kallela M., Schreiber C.P., MacGregor E.A., Silberstein S.D.et al. (2009) Short-term frovatriptan for the prevention of difficult-to-treat menstrual migraine attacks, Cephalalgia doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01840.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Calhoun A., Ford S. (2008) Elimination of menstrual-related migraine beneficially impacts chronification and medication overuse. Headache 48: 1186–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumnijaraki T., Sunyavivat S., Onthuam Y., Udomprasetgurl V. (1984) Study on the factors associated with contraception discontinuation in Bangkok. Contraception 29: 241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson N.J., Lea R.A., Quinlan S., Macmillan J., Griffiths L.R. (2004) The estrogen receptor 1 G594a polymorphism is associated with migraine susceptibility in two independent case/control groups. Neurogenetics 5: 129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson N.J., Lea R.A., Quinlan S., Macmillan J., Griffiths L.R. (2005) Investigation of hormone receptor genes in migraine. Neurogenetics 6: 17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier E.G., Bomhof M.A., Neven A.K., Van Duijn N.P. (2003) Menstrual migraine in a representative Dutch population sample: prevalence, disability and treatment. Cephalalgia 23: 302–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P., Fursdon-Davies C., Rees M.C. (2003) Progestogens for menstrual migraine. J Br Menopause Soc 9: 134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond M.L., Cady R.K., Mao L., Biondi D.M., Finlayson G., Greenberg S.J.et al. (2008) Characteristics of migraine attacks and responses to almotriptan treatment: a comparison of menstrually related and nonmenstrually related migraines. Headache 48: 248–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowson A.J., Kilminster S.G., Salt R., Clark M., Bundy M.J. (2005) Disability associated with headaches occurring inside and outside the menstrual period in those with migraine: a general practice study. Headache 45: 274–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowson A.J., Massiou H., Aurora S.K. (2005) Managing migraine headaches experienced by patients who self-report with menstrually related migraine: a prospective, placebo-controlled study with oral sumatriptan. J Headache Pain 6: 81–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzoljic E., Sipetic S., Vlajinac H., Marinkovic J., Brzakovic B., Pokrajac M.et al. (2002) Prevalence of menstrually related migraine and nonmigraine primary headache in female students of Belgrade university. Headache 42: 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman A., Gallo M.F., Nichols M.D., Jensen J.T., Schulz K.F., Grimes D.A. (2006) Continuous versus cyclic use of combined oral contraceptives for contraception: Systematic Cochrane Review of randomized controlled trials. Hum Reprod 21: 573–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granella F., Sances G., Allais G., Nappi R.E., Tirelli A., Benedetto C.et al. (2004) Characteristics of menstrual and nonmenstrual attacks in women with menstrually related migraine referred to headache centres. Cephalalgia 24: 707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granella F., Sances G., Zanferrari C., Costa A., Martignoni E., Manzoni G.C. (1993) Migraine without aura and reproductive life events: a clinical epidemiological study in 1300 women. Headache 33: 385–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti M., Mauri M., Barrila C., Guidotti F., Belloni C. (2007) Frovatriptan vs. transdermal oestrogens or naproxen sodium for the prophylaxis of menstrual migraine. J Headache Pain 8: 283–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (IHS). (2004) The International Classification of Headache Disorders (2nd Edition). Cephalalgia 24: 1–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdaway I.M., Parr C.E., France J. (1991) Treatment of a patient with severe menstrual migraine using the depot LHRH analogue zoladex. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol 31: 164–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes C.B., Linet M.S., Stewart W.F., Celentano D.D., Lipton R.B., Szklo M. (1995) Relationship of headache to phase of the menstrual cycle among young women: a daily diary study. Neurology 45: 1076–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibler J.L., Rhudy J.L., Penzien D.B., Rains J.C., Meeks G.R., Bennett W.et al. (2005) Hormones, menstrual distress, and migraine across the phases of the menstrual cycle. Headache 45: 1181–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguardia K.D., Fisher A.C., Bainbridge J.D., Lococo J.M., Friedman A.J. (2005) Suppression of estrogen-withdrawal headache with extended transdermal contraception. Fertil Steril 83: 1875–1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loder E., Silberstein S.D., Abu-Shakra S., Mueller L., Smith T. (2004) Efficacy and tolerability of oral zolmitriptan in menstrually associated migraine: a randomized, prospective, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 44: 120–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor E.A. (2007) Menstrual migraine: a clinical review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 33: 36–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor E.A., Brandes J., Eikermann A., Giammarco R. (2004) Impact of migraine on patients and their families: the migraine and zolmitriptan evaluation (MAZE) survey-phase III. Curr Med Res Opin 20: 1143–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor E.A., Chia H., Vohrah R.C., Wilkinson M. (1990) Migraine and menstruation: a pilot study. Cephalalgia 10: 305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor E.A., Frith A., Ellis J., Aspinall L., Hackshaw A. (2006) Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology 67: 2159–2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor E.A., Guillebaud J. (1998) Combined oral contraceptives, migraine and ischaemic stroke. Clinical and Scientific Committee of the Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care and the Family Planning Association. BrJ Fam Plann 24: 55–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor E.A., Hackshaw A. (2004) Prevalence of migraine on each day of the natural menstrual cycle. Neurology 63: 351–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor E.A., Igarashi H., Wilkinson M. (1997) Headaches and hormones: subjective versus objective assessment. Headache Q 8: 126–136 [Google Scholar]

- Mannix L.K., Savani N., Landy S., Valade D., Shackelford S., Ames M.H.et al. (2007) Efficacy and tolerability of naratriptan for short-term prevention of menstrually related migraine: data from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Headache 47: 1037–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin V., Cady R., Mauskop A., Seidman L.S., Rodgers A., Hustad C.M.et al. (2008) Efficacy of rizatriptan for menstrual migraine in an early intervention model: a prospective subgroup analysis of the rizatriptan tame (treat a migraine early) studies. Headache 48: 226–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin V., Wernke S., Mandell K., Zoma W., Bean J., Pinney S.et al. (2003) Medical oophorectomy with and without estrogen add-back therapy in the prevention of migraine headache. Headache 43: 309–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massiou H., Jamin C., Hinzelin G., Bidaut-Mazel C. (2005) Efficacy of oral naratriptan in the treatment of menstrually related migraine. Eur J Neurol 12: 774–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschiano F., Allais G., Grazzi L., Usai S., Benedetto C., D'Amico D.et al. (2005) Naratriptan in the short-term prophylaxis of pure menstrual migraine. Neurol Sci 26(Suppl. 2): s162–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S.C., Muse K.N. (1997) Effective treatment of severe menstrual migraine headaches with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and 'add-back' therapy. Fertil Steril 67: 390–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattero G., Allais G., De Lorenzo C., Ferrando M., Ferrari P., Benedetto C.et al. (1991) Biological and clinical effects of naproxen sodium in patients with menstrual migraine. Cephalalgia 11: 201–2021742776 [Google Scholar]

- Nett R., Landy S., Shackelford S., Richardson M.S., Ames M., Lener M. (2003) Pain-free efficacy after treatment with sumatriptan in the mild pain phase of menstrually associated migraine. Obstet Gynecol 102: 835–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nett R., Mannix L.K., Mueller L., Rodgers A., Hustad C.M., Skobieranda F.et al. (2008) Rizatriptan efficacy in ICHD-II pure menstrual migraine and menstrually related migraine. Headache 48: 1194–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman L., Mannix L.K., Landy S., Silberstein S., Lipton R.B., Putnam D.G.et al. (2001) Naratriptan as short-term prophylaxis of menstrually associated migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 41: 248–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman L.C., Lipton R.B., Lay C.L., Solomon S. (1998) A pilot study of oral sumatriptan as intermittent prophylaxis of menstruation-related migraine. Neurology 51: 307–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffenrath V. (1993) Efficacy and safety of percutaneous estradiol vs. placebo in menstrual migraine. Cephalalgia 13: 244 [Google Scholar]

- Pradalier A., Vincent D., Beaulieu P., Baudesson G., Launey J.-M. (1994) Correlation between estradiol plasma level and therapeutic effect on menstrual migraine. In Rose F. (ed.), New Advances in Headache Research. London, Smith-Gordon [Google Scholar]

- Sances G., Martignoni E., Fioroni L., Blandini F., Facchinetti F., Nappi G. (1990) Naproxen sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Headache 30: 705–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J., Solbach P., Damasio H., Baumel B., Corbett J., Al E. (1985) A Comparison of naproxen sodium to propranolol hydrochloride and a placebo control for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. Headache 25: 320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein S.D., Armellino J.J., Hoffman H.D., Battikha J.P., Hamelsky S.W., Stewart W.F.et al. (1999) Treatment of menstruation-associated migraine with the nonprescription combination of acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine: results from three randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Clin Ther 21: 475–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein S.D., Elkind A.H., Schreiber C., Keywood C. (2004) A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology 63: 261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits M.G., Van Der Meer Y.G., Pfeil J.P., Rijnierse J.J., Vos A.J. (1994) Perimenstrual migraine: effect of estraderm TTS and the value of contingent negative variation and exteroceptive temporalis muscle suppression test. Headache 34: 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville B.W. (1972) The role of estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology 22: 355–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville B.W. (1975a) Estrogen-withdrawal migraine. I. Duration of exposure required and attempted prophylaxis by premenstrual estrogen administration. Neurology 25: 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville B.W. (1975b) Estrogen-withdrawal migraine II. Attempted prophylaxis by continuous estradiol administration. Neurology 25: 245–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner T.J., MacGregor E.A., Davies P.T.G. (2007) Guidelines for All Healthcare Professional in the Diagnosis and Management of Migraine, TensionType, Cluster and Medication Overuse Headache; (3rd edition) Available at: http://216.225.288.243/upload/NS_BASH/BASH_guidelines_2007.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W.F., Lipton R.B., Chee E., Sawyer J., Silberstein S.D. (2000) Menstrual cycle and headache in a population sample of migraineurs. Neurology 55: 1517–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W.F., Wood C., Reed M.L., Roy J., Lipton R.B. (2008) Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia 28: 1170–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulak P., Willis S., Kuehl T., Coffee A., Clark J. (2007) Headaches and oral contraceptives: impact of eliminating the standard 7-day placebo interval. Headache 47: 27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely B., Meeryman S., Post G. (1989) Prophylactic effects of naproxen sodium on perimenstrual headache: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 9: 452–453 [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman M.M., Hee A., Emeribe U., Silberstein S. (2008) Oral zolmitriptan in the short-term prevention of menstrual migraine: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs 22: 877–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch K.M., Brandes J.L., Berman N.E. (2006) Mismatch in how oestrogen modulates molecular and neuronal function may explain menstrual migraine. Neurol Sci 27(Suppl. 2): S190–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wober C., Brannath W., Schmidt K., Kapitan M., Rudel E., Wessely P.et al. (2007) Prospective analysis of factors related to migraine attacks: the pamina study. Cephalalgia 27: 304–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2004) Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. Geneva, WHO; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]