Abstract

RNA interference (RNAi) is a powerful strategy for studying the phenotypic consequences of reduced gene expression levels in model systems. To develop a method for the rapid characterization of the developmental consequences of gene dysregulation, we tested the use of RNAi for “transient transgenic” knockdown of mRNA in mouse embryos. These methods included lentiviral infection as well as transposition using the Sleeping Beauty (SB) and PiggyBac (PB) transposable element systems. This approach can be useful for phenotypic validation of putative mutant loci, as we demonstrate by confirming that knockdown of Prdm16 phenocopies the ENU-induced cleft palate (CP) mutant, csp1. This strategy is attractive as an alternative to gene targeting in embryonic stem cells, as it is simple and yields phenotypic information in a matter of weeks. Of the three methodologies tested, the PB transposon system produced high numbers of transgenic embryos with the expected phenotype, demonstrating its utility as a screening method.

Introduction

The production of targeted mutations in mice remains the gold standard for the analysis of the loss-of-function studies of specific genes in mammals. However, even with the emergence of large-scale knockout mouse resources, such as those of the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (http://www.knockoutmouse.org/), generation of such mutants using embryonic stem (ES) cells may still require substantial time and resources. In particular, this approach is difficult to pursue for high throughput applications. For instance, linkage and association studies for mutations or strain-specific traits may yield a large number of positional candidate genes, which may require testing individually to assess causality. Similarly, microarray analyses typically result in lists of differentially expressed genes, with little indication regarding which ones may be key regulators. An efficient methodology to rapidly screen genes in vivo would enhance the functional analysis of outputs from high throughput screening.

The discovery of RNA interference (RNAi) and its application in mammals has provided a new avenue to study the consequences of reduced gene expression [1], [2]. In this process, short 19–25 nt double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) duplexes mediate the degradation of mRNA transcripts that contain an exact match to the dsRNA sequence (reviewed in [3]). This occurs through the recruitment of the RNase III enzyme, Dicer, followed by a multicomponent nuclease complex known as RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex). Alternatively, mismatched dsRNAs can lead to reduced gene activity through the suppression of protein translation [4].

Current methods for the utilization of RNAi as a means to test the effect of loss of gene function involve direct introduction of short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or expression of precursor short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) expressed on plasmids and retroviruses [2], [5], [6]. shRNA-expressing vector systems, including lentivirus and transposable elements vectors, provide highly efficient, stable shRNA expression in cultured cells and transgenic mammals (reviewed in [7], [8]). Lentiviral infection of ES cells, morula, or single-cell embryos (via injection into the perivitelline space) has been successfully employed for transgenesis in mice and subsequent RNAi knockdown [9], [10]. However, these protocols are not routinely employed in microinjection facilities. In contrast, the Sleeping Beauty (SB) and PiggyBac (PB) transposon systems can be employed using standard microinjection protocols that yield substantially higher transgenic efficiency than traditional pronuclear DNA injections [7], [11], [12], [13 and this study]. These transposon systems have two-components, the first of which is a transposon vector containing an expression cassette flanked by terminal inverted repeats that have binding sites for the SB or PB transposase in direct orientation, termed IR/DRs. The second component is SB or PB transposase mRNA, which can be co-expressed from a plasmid or transcribed in vitro. The specific transposase mediates transposition via a “cut and paste” mechanism in which the transposable element is excised from a donor plasmid, followed by its integration into the host genome at a specific target DNA sequence: TA for SB; TTAA for PB. SB transposons have recently been used in combination with RNAi to achieve stable reduction of gene expression in cultured cells [14].

One of several potential applications of a rapid method for RNAi knockdown in embryos is the validation of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced mutations. ENU screens performed in mice have successfully identified a wide spectrum of abnormal phenotypes affecting development [15], [16], [17], [18]. The mutations induced by ENU can affect non-coding regulatory sequences and will not be discovered by the usual exon-directed sequencing analysis. In addition, it is possible that multiple ENU-induced mutations are present within the genetically defined recombinant interval carrying the causal locus. Therefore, even when a putative mutation is identified, independent validation of the positionally-cloned gene mutation is desirable. We explored whether RNAi could be efficiently used for targeted mutagenesis by employing a “transient transgenic” protocol; i.e., transgenic analysis in which microinjected embryos are not used to generate stable lines, but rather examined directly. Similar approaches to assay loss of gene function have been used successfully in zebrafish [19], [20].

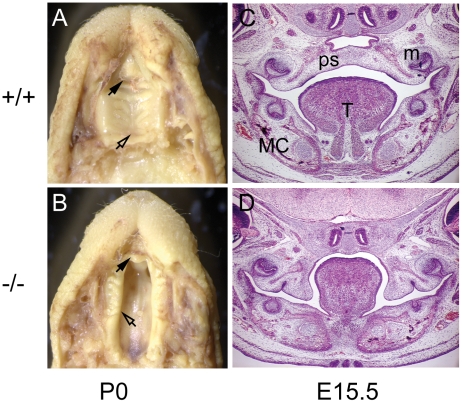

We have previously identified the cleft secondary palate 1 (csp1) mutant in an ENU mutagenesis screen for recessive late-term developmental anomalies that model human birth defects [15]. Newborn homozygous csp1 mutant pups on an FVB/NJ strain background exhibit cleft secondary palate with virtually complete penetrance and die within 24 hours (Fig. 1A and B). Positional cloning revealed that this mutant carries an intronic splicing mutation in the Prdm16 zinc finger transcription factor gene on distal chromosome 4. We have since confirmed the etiology of the csp1 mutation in Prdm16 by carrying out a complementation test with a Prdm16 gene trap mutation [21].

Figure 1. The recessive ENU-induced csp1 mutation in Prdm16 exhibits cleft secondary palate.

Homozygous csp1 mutants are born with cleft palate (CP) and die within 24 hours after birth (A–D). Bouin's fixed wild type (A) and csp1 (B) mutant newborn pups with CP (A and B). The unaffected primary palates (black arrowheads) and fused or cleft secondary palate are evident (open arrowheads in A and B, respectively). Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained coronal sections through wild-type (C) and csp1 mutant (D) embryonic day (E) 15.5 embryos show impaired palate shelf elevation in mutants. Tongue, T; palate shelf, ps; Meckel's cartilage, mc and molar, m.

In this study, we utilized several variants of lentivirus and SB and PB transposons to express Prdm16-specific shRNAs and compared their efficacy for transgenesis and phenotypic validation of the mutant allele. RNAi knockdown of Prdm16 using each system successfully recapitulated the csp1 CP phenotype in transient transgenic mouse embryos. Lentiviral infection yielded high transgenic efficiency with modest phenotypic penetrance. SB transposon-mediated transgenesis resulted in low transgenic efficiency with high phenotypic penetrance. However, nonviral PB transposon-mediated transgenesis yielded both high transgenic efficiency and high phenotypic penetrance. As this system is amenable for use in any laboratory and transgenic facility, it represents an ideal means for the rapid analysis of the consequences of mRNA knockdown in a mammalian system.

Results

In mice, secondary palate development begins with palate shelf outgrowth from the maxillary prominences at E12.5, followed by downward growth along either side of the tongue and then concurrent rapid shelf elevation and flattening of the tongue at approximately E14. Fusion occurs between the medial edge epithelium (MEE) of the two palate shelves through a combination of epithelial-mesenchymal transformation, cell migration and apoptosis [22], [23]. Apposition and fusion of the palatal shelves at the midline occurs by E14.5 in most mouse strains. We initiated transient transgenic RNAi experiments in mice to examine the effect of reduced Prdm16 expression in E16.5 mouse embryos, by which time wild type palate shelves have elevated and fused [23].

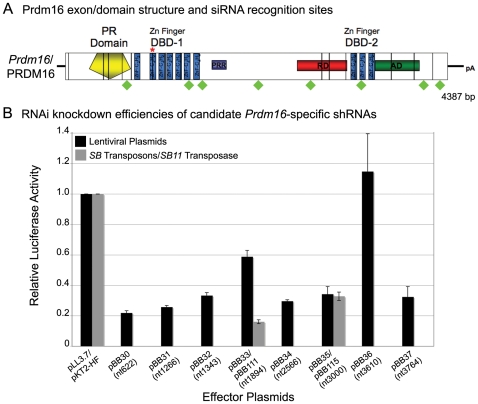

Selection of efficient Prdm16-specific shRNAs for RNAi

Prdm16 is comprised of 17 exons, and the Prdm16 transcript is 4394 nucleotides and contains an open reading frame that encodes a 1277 amino acid protein (Fig. 2A, NM_027504) [24]. To identify a sequence that would mediate effective RNAi, we selected eight Prdm16-specific siRNA sequences that meet eight criteria previously associated with efficient siRNA knockdown (Table 1, Fig. 2A) [25]. We utilized sense and antisense shRNA oligonucleotides comprised of the sense siRNA target sequence, a stem loop sequence, the antisense siRNA target sequence, a 5-thymidine terminator sequence and appropriate overhangs for cloning (Table 1) [10]. Annealed sense and antisense shRNA oligonucleotides were ligated downstream of the human U6 small nuclear RNA polymerase III promoter in the lentiviral vector, pLentiLox3.7 (pLL3.7; Fig. 3B), which also contains a CMV-eGFP expression cassette for visualization of infected cells [10].

Figure 2. Prdm16-specific shRNA selection and validation of RNAi knock down efficiency.

Schematic of Prdm16 mRNA and protein structure (A). Vertical black lines demarcate exon boundaries. Conserved functional domains include a Positive Regulatory (PR) domain, two multi-fingered zinc finger DNA binding domains (DBD-1 and DBD-2), repressor domain (RD), acidic domain (AD) and Proline-rich region (PRR). Eight Prdm16-specific shRNAs are shown with respect to their positions within the Prdm16 coding sequence (green diamonds). The red inverted “V” depicts the alternatively spliced exon 16. Prdm16 mRNA knock down efficiency in vitro mediated by expression of the candidate shRNAs from pLL3.7 lentivirus plasmids or CpG-free Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposons measured by relative luciferase activity (B). RNAi knock down values for effector shRNAs were normalized against the knockdown efficiency of an empty plasmid control transfection, and transfection efficiencies were calculated based upon the co-transfection of a Renilla luciferase control expression plasmid. Transfections were performed in duplicate for screening purposes, and error bars show the standard deviations.

Table 1. Prdm16-specific shRNA expression plasmid sequences.

| Plasmid # | Name | Plasmid backbone | Position of siRNA in cds | Sequence (5′-3′) |

| 30 | nt622 | pLL3.7 | 684–702 | F:TGTTGGTGCATGTGAAAGAATTCAAGAGATTCTTTCACATGCACCAACTTTTTTC |

| R:TCGAGAAAAAAGTTGGTGCATGTGAAAGAATCTCTTGAATTCTTTCACATGCACCAACA | ||||

| 31 | nt1266 | pLL3.7 | 1328–1346 | F:TGGACGCAGATCAAGTGCAATTCAAGAGATTGCACTTGATCTGCGTCCTTTTTTC |

| R:TCGAGAAAAAAGGACGCAGATCAAGTGCAATCTCTTGAATTGCACTTGATCTGCGTCCA | ||||

| 32 | nt1343 | pLL3.7 | 1405–1423 | F:TGAGGGCAAGAACCATTACATTCAAGAGATGTAATGGTTCTTGCCCTCTTTTTTC |

| R:TCGAGAAAAAAGAGGGCAAGAACCATTACATCTCTTGAATGTAATGGTTCTTGCCCTCA | ||||

| 33 | nt1894 | pLL3.7 | 1956–1974 | F:TGGACAGTGACAGAGACAAATTCAAGAGATTTGTCTCTGTCACTGTCCTTTTTTC |

| R:TCGAGAAAAAAGGACAGTGACAGAGACAAATCTCTTGAATTTGTCTCTGTCACTGTCCA | ||||

| 34 | nt2566 | pLL3.7 | 2628–2646 | F:TGCATTATGCTAAGCCTTCATTCAAGAGATGAAGGCTTAGCATAATGCTTTTTTC |

| R:TCGAGAAAAAAGCATTATGCTAAGCCTTCATCTCTTGAATGAAGGCTTAGCATAATGCA | ||||

| 35 | nt3000 | pLL3.7 | 3065–3083 | F:TGGAACATCCACAACAAAGATTCAAGAGATCTTTGTTGTGGATGTTCCTTTTTTC |

| R:TCGAGAAAAAAGGAACATCCACAACAAAGATCTCTTGAATCTTTGTTGTGGATGTTCCA | ||||

| 36 | nt3610 | pLL3.7 | 3675–3693 | F:TGGAAGCATTTGAAGTTAAATTCAAGAGATTTAACTTCAAATGCTTCCTTTTTTC |

| R:TCGAGAAAAAAGGAAGCATTTGAAGTTAAATCTCTTGAATTTAACTTCAAATGCTTCCA | ||||

| 37 | nt3764 | pLL3.7 | 3829–3847 | F:TGATGCTTGGTTGAACATCATTCAAGAGATGATGTTCAACCAAGCATCTTTTTTC |

| R:TCGAGAAAAAAGATGCTTGGTTGAACATCATCTCTTGAATGATGTTCAACCAAGCATCA | ||||

| 111 | nt1894 | pKT2-HF (SB) | 1956–1974 | F:ACCTCGGACAGTGACAGAGACAAATTCAAGAGATTTGTCTCTGTCACTGTCCTTTTTTTT |

| R:CAAAAAAAAAAAGGACAGTGACAGAGACAAATCTCTTGAATTTGTCTCTGTCACTGTCCG | ||||

| 113 | nt622 | pKT2-HF (SB) | 684–702 | F:ACCTCGTTGGTGCATGTGAAAGAATTCAAGAGATTCTTTCACATGCACCAACTTTTTTTT |

| R:CAAAAAAAAAAAGTTGGTGCATGTGAAAGAATCTCTTGAATTCTTTCACATGCACCAACG | ||||

| 114 | nt622-scrambled | pKT2-HF (SB) | NA | F:ACCTCGCGGAGAAAGTGGATTTATTTCAAGAGAATAAATCCACTTTCTCCGCTTTTTTTT |

| R:CAAAAAAAAAAAGCGGAGAAAGTGGATTTATTCTCTTGAAATAAATCCACTTTCTCCGCG | ||||

| 160 | Empty U6-no shRNA; CMV-eGFP | pKT2-HF (SB) | NA | None |

| 161 | U6-nt1266 shRNA; CMV-eGFP | pKT2-HF (SB) | 1328–1346 | Same as pBB31 |

| 162 | U6-nt1894 shRNA; CMV-eGFP | pKT2-HF (SB) | 1956–1974 | Same as pBB33 |

| 181 | Empty U6-no shRNA | pKT2-HF (SB) | NA | None |

| 182 | U6-nt1266 shRNA | pKT2-HF (SB) | 1328–1346 | Same as pBB31 |

| 183 | U6-nt1894 shRNA | pKT2-HF (SB) | 1956–1974 | Same as pBB33 |

| 205 | U6-nt622 shRNA | pCyL50 (PB) | 684–702 | Same as pBB30 |

Underlined nucleotides in each oligonucleotide sequence represent the sense and antisense sequence-specific siRNA target sequence within Prdm16.

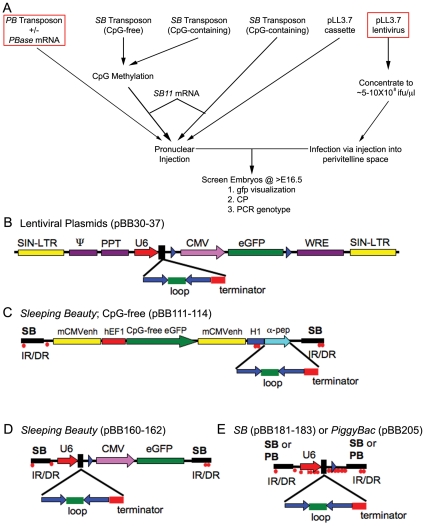

Figure 3. Strategy for gene mutation validation and candidate gene screening using transient transgenic RNAi knockdown.

Flow chart outlining the experimental method and the classes of transgenic delivery vehicles and their variants (A). Creation of various shRNA-expressing lentivirus and Sleeping Beauty (SB) and PiggyBac (PB) transposon plasmids (B–E). B) pLL3.7 lentivirus plasmid was described previously and contains a U6–shRNA; CMV-eGFP expression cassette [10]. SIN-LTR, self-inactivating long terminal repeat; Ψ, HIV packaging signal; cPPT, central polypurine track; MCS, multiple cloning site; CMV, cytomegalovirus promoter; WRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus response element. Sense and antisense sequences that form the stem of the stem loop shRNA sequence are shown by the solid blue arrows; the loop sequence, green bar and the terminator, red bar. C) CpG-free EF1-GFP; H1-shRNA SB transposons. IR/DR, inverted/direct terminal repeats recognized by SB transposase; mCMVenh, mouse cytomegalovirus enhancer sequence; hEF1, human EF1 promoter; eGFP, synthetic GFP coding sequence; H1, human pol III promoter; α-pep, lacZ alpha peptide for blue-white selection. D) CpG-containing U6-shRNA; CMV-eGFP from pLL3.7 in the SB transposon. E) U6-shRNA expression cassette from pLL3.7 in the SB and PB transposons. CpG dinucleotides methylated by SssI methylase (red dots) in SB transposon experiments are shown.

We used a luciferase reporter system to assay the effectiveness of the shRNAs. The coding sequence for a splice variant of Prdm16 in which exon 16 is absent was subcloned into the 3′ UTR of the luciferase gene contained on a modified pGL3 Firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3-DEST-Prdm16) [26]. To measure knockdown efficiency, luciferase activity was measured after co-transfection into 293T cells of each shRNA-expressing lentivirus plasmid with pGL3-DEST-Prdm16 and normalized to the activity obtained from a co-transfected pRL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmid. All shRNA lentiviral plasmids showed knockdown activity, except for pBB36 (nt 3610), which is in the exon that is not included in the pGL3-DEST-Prdm16 reporter plasmid (Fig. 2B). pBB30 (nt 622) and pBB31 (nt 1266) facilitated the strongest knockdown, to approximately 20% of wild-type expression levels. Transfection of Prdm16-specific shRNA-expressing SB transposon plasmids (pBB111, nt1894; pBB115, nt3000) also facilitated strong knockdown activity in this assay (Fig. 2B).

Lentivirus and Sleeping Beauty/PiggyBac transposons expressing Prdm16-specific shRNAs recapitulate the csp1 mutant CP phenotype in transient transgenic mouse embryos

To assay the developmental consequences of RNAi knockdown of Prdm16 in mice, we performed “transient” transgenic analysis in which Prdm16-specific shRNAs were introduced into mouse embryos and litters were examined at E16.5 for the presence of CP and co-expression of GFP (Fig. 3A). We utilized lentivirus and SB or PB transposons (Fig. 3B-E) and assayed variables including shRNA knockdown efficiency, transgene delivery vehicle, transposon methylation status and size and presence or absence of the GFP reporter. For plasmid DNA injection and lentiviral infection, we used the pBB30, pBB33 and empty pLL3.7 plasmids described above. For SB transposon-mediated delivery of Prdm16-specific shRNAs, methylated or unmethylated transposon DNA and in vitro-transcribed 5′capped Sleeping Beauty transposase (SB11) mRNA [27] was injected into single cell embryos [11], [12]. Similarly, a PB transposon expressing a Prdm16-specific shRNA was co-injected with 5′-capped PiggyBac transposase (PBase) mRNA. A summary of all transient transgenic RNAi experiments is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Combined summary of transgenic RNAi injections.

| Constructs | Methylation | # Embryos | TG | CP | TG Frequency | CP Frequency | Penetrance | CP, not TG |

| Lentivirus plasmid | No | 88 | 16 | 0 | 0.18 | 0 | NA | 0 |

| empty | ||||||||

| U6; GFP | ||||||||

| Lentivirus plasmids | No | 248 | 8 | 0* | 0.03 | 0* | 0* | 0 |

| nt1266, nt1894 | ||||||||

| U6; GFP | ||||||||

| Lentivirus plasmid | No | 55 | 26 | 5* | 0.47 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 1 |

| nt622 | ||||||||

| U6; GFP | ||||||||

| SB | Yes | 56 | 32 | 0 | 0.57 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| nt622 scrambled | ||||||||

| CpG-free H1; GFP | ||||||||

| SB | Yes | 79 | 54 | 0 | 0.68 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| nt622 | ||||||||

| CpG-free H1; GFP | ||||||||

| SB | No | 32 | 4 | 0 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Empty | ||||||||

| U6; GFP | ||||||||

| SB | No | 108 | 5 | 4 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 0 |

| nt1266, nt1894 | ||||||||

| U6; GFP | ||||||||

| SB | No | 57 | 4 | 3* | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.50* | 1 |

| nt1266 | ||||||||

| U6; no GFP | ||||||||

| SB | Yes | 73 | 12 | 2 | 0.16$ | 0.03 | 0.17$ | 0 |

| nt1266 | ||||||||

| U6; no GFP | ||||||||

| PB | No | 59 | 10 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0 |

| nt622 | ||||||||

| U6; no GFP | ||||||||

| No PBase control | ||||||||

| PB; nt622 | No | 112 | 52 | 12 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0 |

| nt622 | ||||||||

| U6; no GFP | ||||||||

| PBase | ||||||||

| PB | No | 20 | 2 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0 |

| nt622 | ||||||||

| U6; no GFP | ||||||||

| 4-5X PBase |

*Denotes one or more transgenic embryos showing early embryonic growth arrest prior to palate fusion.

Three of 24 resorptions were transgenic.

TG, transgenic embryos; CP, cleft palate; Penetrance, number of transgenic embryos with CP.

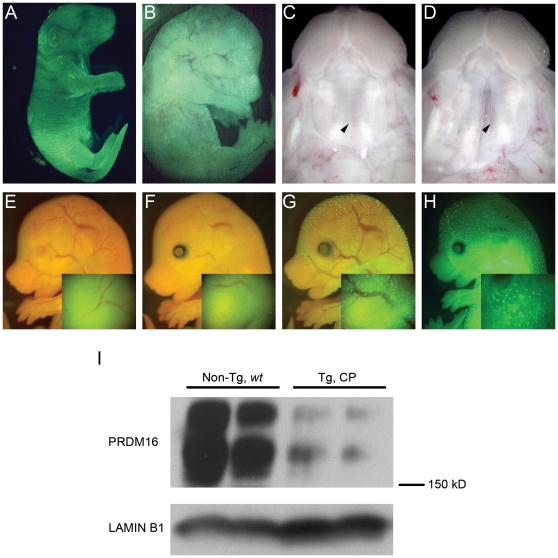

To begin we used traditional transgenic methodologies for injection of pLL3.7, pBB30 and pBB33 plasmid DNA into single FVB/J mouse cells (Table 2). Control pLL3.7 injections yielded 18% transgenic newborn pups with strong, ubiquitous GFP expression (Fig. 4A), but pBB30 and pBB33 yielded substantially less transgenic embryos and none with CP. To produce transgenic embryos with increased frequency, we first performed transient transgenic experiments by lentiviral infection. High titer (∼0.5–1.0×109 ifu/ml) lentivirus derived from pBB30 was injected into the perivitelline space of single FVB/NJ mouse oocytes (Table 2). Transgenic efficiency was 47% (26/55), but GFP expression was visible in only 7% (4/55) of embryos (Fig. 4B). 16% (4/26) of transgenic embryos exhibited CP (Fig. 4D compared to wild type embryo in Fig. 4C), with an additional embryo arresting prior to palatogenesis. One CP embryo was not transgenic by PCR genotyping. Lentiviral transgenesis proved to be an efficient strategy to validate the csp1 mouse mutation, but the specialized training, certification and facilities required for lentivirus experiments, as well as the non-trivial task of isolating high titer lentivirus, may discourage the routine use of this strategy.

Figure 4. Transient transgenic RNAi knockdown of Prdm16 in mice recapitulates the recessive csp1 ENU mutant phenotype.

A) Strong GFP expression driven by the CMV-eGFP cassette with plasmid DNA injection of pLL3.7. B) Similarly strong ubiquitous GFP expression visible in some lentivirus infected transient transgenic Prdm16 RNAi knock down E16.5 embryos. Wild-type (C) and transgenic (D) E16.5 embryos with fused and cleft palate, respectively, representative of the CP phenotype observed in affected transgenic embryos produced using delivery vehicles reported in this study. Variable GFP expression pattern observed in transgenic embryos carrying CpG-free SB transposons with the H1-GFP cassette, also representative of the variability of GFP expression pattern observed in all constructs utilizing a GFP expression cassette (E–H). Insets consist of higher magnification images taken of head regions from these same embryos. I) Western blot analysis for PRDM16 in nuclear lysates isolated from non-transgenic wild type (Non-Tg, wt) and transgenic CP E16.5 embryonic heads derived from pronuclear injection of a Prdm16-specific shRNA-expressing PB transposon. LAMIN B1 expression is provided as a loading control.

The nonviral SB and PB transposon systems have the potential to efficiently generate transient transgenic embryos expressing gene-specific shRNAs. Since CpG methylation of SB transposons can improve transposition frequency [28], [29], we first used the SssI methylase-treated CpG-free SB transposons and SB11 mRNA for transient transgenic experiments (Fig. 3C, Table 2). We achieved high transgenic efficiency, 57% and 68%, with a control transposon (pBB114, scrambled nt622 shRNA) and pBB113 (nt622), respectively, accompanied by variable GFP marker expression (Fig. 4E-H). However, we observed no embryos with CP upon dissection at E15.5 (Table 2).

Therefore, we altered several variables in an attempt to improve shRNA and GFP expression. First, we used the U6 Pol III promoter, which drives shRNA expression with greater efficiency than the H1 Pol III promoter [30]. We subcloned the CpG-containing U6-shRNA; CMV-eGFP expression cassette (1.94 kb) from pLL3.7 into the SB transposon plasmid. GFP expression is robust when expressed from this cassette in vivo (Fig. 4A). We did not methylate these transposons before injection due to the presence of many CpG dinucleotides (Fig. 3A, data not shown). Transgenic injection of pBB160 (control), pBB161 (nt1266) and pBB162 (nt1894) produced much lower transgenic efficiencies than with the CpG-free transposons, (13%, 5% and 5%, respectively), However, the small number of transgenic embryos we obtained showed frequent CP (Table 2 and Table S1).

As CMV-driven GFP expression was variable and often difficult to visualize; and since we screen all embryos for phenotypic abnormalities, the utility of the GFP marker in these transposons is limited. Therefore, we removed the CMV-eGFP expression cassette to generate a smaller transposon containing only the U6-shRNA expression cassette (0.56 kb, Fig. 3E). Methylation by CpG methylases and reduced transposon size address two variables known to improve SB transposition efficiency [27] (Largaespada, D.A., personal communication). We performed multiple transgenic injections to investigate these variables and observed little difference in outcome (Table 2).

In contrast, utilization of a PB transposon that expresses a Prdm16-specific shRNA driven by the U6 Pol III promoter proved much more successful (Table 2 and Table S1). We compared the transgenic efficiency and phenotypic penetrance achieved utilizing differing amounts of the PB transposon plasmid DNA and PBase mRNA. Control experiments with no co-injected PBase mRNA produced yielded 59 embryos, 10 (17%) of which were transgenic with 1 (2%) exhibiting CP. Therefore, transgenic efficiency was within the normal range for a traditional transgenic DNA injection experiment, and the CP penetrance in transgenic embryos was 10%. The same amount of transposon DNA (∼2.0 µg/ml) co-injected with PBase mRNA (23 µg/ml) dramatically increased transgenic efficiency (68%), CP embryos (11%) and penetrance (16%). A substantial increase in PBase mRNA concentration (92 µg/ml) did not increase these values. On the contrary, we observed a marked increase in resorptions, decrease in live embryos and obtained only 10% (2/20) transgenic efficiency with only 1 affected embryo (5%). A slight reduction in PB transposon concentration (1.4 µg/ml) co-injected with lower PBase mRNA concentrations (17 and 23 µg/ml) yielded the most ideal conditions for these validation studies, increased transgenic efficiency (32% and 42%) and penetrance (29% and 27%) in 22 and 62 embryos, respectively. On average, use of 1.4–2.0 µg/ml PB transposon DNA and 17–23 µg/ml PBase mRNA resulted in 46% transgenic efficiency and 23% CP penetrance (Table 2).

To confirm in vivo knockdown of Prdm16 in these embryos, nuclear protein lysates were isolated from two non-transgenic wild type and two transgenic CP embryonic heads harvested from a PB transposon plus PBase mRNA co-injection experiment. Relative PRDM16 protein levels were determined by Western analysis of these nuclear fractions to using a rabbit PRDM16-specific polyclonal antibody (Fig. 4I). Marked reduction of a pair of protein bands just over 150 kD in size in transgenic embryos with CP confirmed successful knockdown of Prdm16. Although the exact nature of these PRDM16 isoforms has not been determined, specific loss of these protein products has been demonstrated previously in mutant mice carrying Prdm16 null alleles [21].

Discussion

We chose to pursue transient transgenic RNAi knockdown during mouse embryogenesis as a means to rapidly validate loss of function gene mutations, which we have identified as part of an ENU mutagenesis screen for late embryonic phenotypic anomalies [15]. Transient transgenic RNAi knockdown has the obvious advantage of speed over standard homologous recombination in ES cells for rapid phenotypic validation or candidate gene screening. Mutant embryos deficient for expression of a gene of interest can be examined within 2–3 weeks of microinjection. Resources such as the RNAi Consortium (http://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/trc) and RNAi Codex (http://cancan.cshl.edu/cgi-bin/Codex/Codex.cgi) increasingly facilitate the selection of gene-specific siRNA sequences to efficiently knock down gene function. Even with the selection of high-scoring siRNA target sequences predicted using bioinformatics tools, one must validate knockdown efficiency experimentally, which we did using a luciferase-based in vitro assay [26]. We examined a variety of vehicles for the delivery of gene-specific shRNAs into mouse embryos with the aim of producing transgenic mouse embryos with high frequency, which is crucial to such a screening strategy, especially given the potential variability of RNAi knockdown efficiency. All of these methods recapitulated the CP phenotype observed in Prdm16 mutant mice. Lentivirus-infection and PB transposon-mediated transgenesis yielded the highest transgenic efficiency and phenotypic penetrance. Our studies were carried out using a single gene, Prdm16, to facilitate the comparative analysis of a multitude of shRNA delivery systems and variables; extension of these studies to additional candidate genes will be undertaken to validate the general application of our strategy.

Lentivirus infection has been used effectively to generate stable transgenic mammalian lines with both constitutive and conditional expression of transgenes and shRNAs [8], [9], [10], [31], [32]. This proved to be a viable strategy for transient transgenic RNAi knockdown in mouse embryos using Prdm16-specific shRNAs, although the specialized training and facilities necessary for working with these pathogens reduces its attractiveness as a universal tool for these studies.

The SB system is also a tractable means to perform in vitro and in vivo transgenic studies of many kinds, including cancer modeling, gene trapping, generation of transgenic mouse lines and insertional mutagenesis [33], [34], [35], [36]. Several factors have been shown to affect the transposition efficiency of SB transposons in vitro. There is a demonstrated decrease in transposition efficiency that is directly proportional to transposon size and SB transposase expression levels over a certain threshold (overproduction inhibition) [27], [37]. CpG methylation of SB transposons and heterochromatin formation has been shown to increase transposon excision from the genome and transposition of a plasmid into the genome, and SB11 transposase shows a high affinity for heterochromatin [28], [29], [38]. Methylation of SB transposons has given rise to very high transgenic efficiency (up to 90%) in mice (Largaespada, D.A., personal communication). However, the heterochromatic state can potentially silence promoter activity, which would mitigate the advantage of increased transposition. We utilized methylated SB transposons containing CpG-free shRNA and GFP expression cassettes to attempt to achieve high transposition/transgenic efficiency without silencing shRNA and GFP expression. We tested many of the variables above in our SB transposon injections and achieved little increase in efficiency (Fig. 3A). We achieved very high transgenic efficiency using CpG-methylated CpG-free SB expression plasmids, but we did not obtain any fetuses that recapitulated the csp1 mutant phenotype (Table S1). We examined transposon size and CpG methylation status via other CpG-containing SB transposons. Generally, these variations all resulted in low transgenic efficiency, but yielded a highly penetrant phenotype. Unfortunately, these attempts to optimize the SB transposition did not produce the high transposition/transgenic efficiency coupled with a high phenotypic penetrance that we desired. Certainly other variables could be adjusted, such as the amount of transposon DNA and SB11 transposase mRNA injected, in order to improve this system; however, given our results using the PB transposon system, we did not pursue further optimization of the SB transposon system. Recently, a hyperactive SB transposase mutant (SB100X) with ∼100-fold increase in transposition efficiency over the first-generation SB transposase enzyme was reported [39]. Pronuclear injection of SB100X transposase and an SB transposon (CAGGS promoter driving Venus expression) into mouse embryos using amounts different than in our SB experiments resulted in 37% transgenic efficiency in newborn mice. Therefore, utilization of the SB100X transposase in combination with our SB shRNA-expressing transposons may improve transgenic efficiency to go along with the high phenotypic penetrance that we observed.

In contrast to our experience using SB transposition, PB transposon-mediated transgenesis yielded a substantial improvement in transgenic efficiency over traditional plasmid DNA injections and produced a highly penetrant phenotype. This result, combined with the observed reasonable phenotypic penetrance, makes PB transposition an attractive, nonviral approach to validate positionally-cloned gene mutations and screen candidate genes. A 4-5-fold increase of PBase mRNA levels resulted in more resorptions, less live embryos and low transgenic efficiency. Transposition efficiency is directly dependent upon increased transposase levels up to a certain threshold level [37]; therefore, our results may reflect this increased transposition efficiency and a corresponding deleterious effect on viability due to increased integration events with higher probability of disrupting essential genes and/or regulatory elements.

Clearly, additional modifications of this system can be considered. The addition of minimal mammalian insulator sequences flanking the shRNA expression cassette, such as the chicken hypersensitive site-4 (cHS4) chromatin insulator, may mitigate the potential negative effect on shRNA expression of methylation differences or position effects. One might also consider additional modifications to this system to more specifically examine loss of gene function during mouse embryogenesis, including gene-specific or temporally-specific RNAi transgenesis using mouse Pol II RNA polymerase or inducible promoter sequences.

In summary, we describe the use of transient transgenic RNAi knockdown to demonstrate the developmental consequences of a loss of function mutation. We carried out a detailed examination of the efficacy of lentivirus- and transposable element-based methods for the delivery of shRNA-expressing transgenes. Lentivirus infection and PB transgenesis achieved comparably favorable transgenic efficiency and phenotypic penetrance; however, the nonviral PB transposon system has significant advantages since no specialized training, equipment or facilities are required. Transient transgenic RNAi knockdown can be a universally tractable, rapid and powerful approach for use in human and mouse genetic studies to validate positionally cloned mutations and to screen candidate genes for developmental phenotypes.

Materials and Methods

shRNA selection and validation

Prdm16-specific shRNAs were chosen using informatics software that screened the Prdm16 coding sequence for short 19-mer sequences meeting eight criteria for efficient knockdown of mRNA expression (score >7) described previously [10], [25]. Eight target sequences showing no homology to other mouse genes were selected for cloning into the pLenti-Lox3.7 (pLL3.7) lentivirus plasmid backbone and subsequent in vitro validation of knockdown efficiency (Table 1) [10]. RNAi knockdown efficiency was determined experimentally using a previously described luciferase reporter strategy [26]. RNAi target cDNA sequence contained in a Gateway Entry vector derived from a Prdm16 EST clone, GenBank Accession No. CB248179.1 [21] was cloned into the 3′ UTR of a modified Firefly luciferase expression plasmid adapted for use as a destination vector in the Gateway cloning system (pGL3-DEST) via a LR clonase reaction to make the pGL3-DEST-Prdm16 (Invitrogen). 100 ng pGL3-DEST-Prdm16, 25 ng pRL-tk (control Renilla luciferase expression plasmid) and 200 ng empty pLL3.7 or Prdm16-specific shRNA expression plasmid were transfected into 293T cells and incubated for 24–36 hours after which cells were lysed and Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity was measured as directed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega) in a Veritas Microplate Luminometer (Turner BioSystems). Relative luciferase activity values were calculated as the ratio of Firefly:Renilla luciferase in each transfected well, and each transfection was performed in duplicate. RNAi knockdown efficiency was taken as the ratio of the relative luciferase activity for the experimental shRNA plasmid over that for the pLL3.7 negative control transfection.

Antibodies and Western blotting

Affinity-purified PRDM16-specific antiserum raised against an N-terminal PRDM16 peptide was described previously [21]. Western blots were performed using established protocols. Nuclear fractions were isolated from embryonic heads as directed using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Nuclear fractions (100 µg) were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to PVDF membrane for 2 hours at 600 mA, and incubated in the presence of PRDM16 N-terminal (1∶7500) and Lamin B1 (1∶1000; Abcam) antisera, followed by antibody detection using the SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce).

Lentiviral plasmid construction

Oligonucleotides containing the sense 19 nt RNAi target sequence followed by a short loop sequence and the reverse and complement 19 nt RNAi target sequence and poly-T terminator sequence. 60 pmoles of each oligonucleotide were annealed to make dsDNA in Annealing Buffer (100 mM Potassium Acetate, 30 mM Hepes-Potassium Hydroxide, pH 7.4 and 2 mM Magnesium Acetate) in a total volume of 50 µl using the following cycling conditions (95°C, 4 min., 70°C, 10 min. followed by incremental decrease (0.1°C/min.) to 4°C. Oligonucleotides were 5′-phosphorylated and designed with 5′ and 3′ overhangs to allow for directional cloning into XhoI/HpaI-digested, Calf Intestinal Phosphatase-treated pLL3.7 plasmid. Ligations were performed using 60 fmoles of annealed oligonucleotides and linearized plasmid in a 10 µl reaction volume using the Quick Ligation Kit (NEB) and transformed into stbl3 chemically competent cells (Invitrogen). Transformants were screened by colony PCR using primers that flank the multiple cloning site of pLL3.7 (Table S2).

Sleeping Beauty and PiggyBac transposon construction

Sleeping Beauty

Empty pKT2-HF transposon plasmid DNA and pT3TS-SB11 transposase expression plasmid were generously provided by David Largaespada (Univ. of Minn.). CpG-free plasmids pMOD-ZGFP::sh, pCpG-H1siRNA and pCpG-mcs (Invivogen) were used to generate CpG-free SB transposons to avoid gene silencing upon CpG methylation via SssI methylase (NEB). pKT2-HF and pCpG-H1siRNA plasmids were digested with EcoRI and HindIII restriction enzymes. The gel-purified H1siRNA expression cassette fragment was ligated into the digested and gel-purified pKT2-HF plasmid to make pKT2-HF-H1siRNA. A CpG-free synthetic GFP coding sequence was amplified from pMOD-ZGFP::sh plasmid DNA using oligonucleotides containing BglII (oBB1018) or NheI (oBB1019) restriction sites at their 5′ ends (Table S2). This PCR product and pCpG-mcs were digested with BglII and NheI restriction enzymes, gel-purified and ligated to make pCpG-GFP. pCpG-GFP and pKT2-HF-H1siRNA plasmids were each digested with EcoRI, and the fragment containing the GFP expression cassette was gel-purified and ligated into the digested pKT2-HF-H1siRNA plasmid to make pKT2-HF-GFP-H1siRNA. Alternative 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotides with overhangs compatible with cloning into BbsI sites of the H1siRNA expression cassette (oBB1022-1033, Table 1) were annealed and ligated into BbsI-digested pKT-HF-GFP-H1siRNA as described previously for pLL3.7. In addition, GFP-minus transposons were created by ligation of annealed oligos into the BbsI sites of pKT2-HF-H1siRNA.

CpG-containing variations of these SB transposons were constructed by removing the CMV-eGFP; U6-shRNA expression cassettes from pLL3.7, pBB30, pBB31 and pBB33 from the pLL3.7 vector backbone by digestion with XbaI and EcoRI restriction enzymes. The pKT2-HF transposon plasmid was digested with SpeI and EcoRI, CIP-treated and ligated to the XbaI/EcoRI-digested CMV-eGFP; U6-shRNA expression cassettes. The empty plasmid backbone is referred to as pKT2-HF-U6-shRNA-GFP. Later these plasmids were digested with HindIII to remove the CMV-eGFP expression cassette to make pKT2-HF-U6-shRNA.

PiggyBac

Empty PB transposon plasmid DNA (pCyL50) and pCMV-PBase expression plasmids were generously provided by Pentau Liu (Sanger). The U6-shRNA cassettes from pBB30 were amplified using primers oBB1336/1337 (504 bp) that contained AscI or PacI restriction sites at their 5′ ends. These PCR products and pCyL50 plasmid DNA were digested with AscI/PacI and ligated together to make control and Prdm16-specific shRNA-expressing PB transposons (Table 1 and Table S2). PvuII digestion excised the IR-U6-nt622shRNA-IR fragment to be used for transgenesis. The PB transposase plasmid used as template for in vitro transcription reactions was constructed as follows. Empty pT3TS plasmid backbone was obtained by digesting pT3TS-SB11 with BglII [40]. The oligonucleotide linker primers oBB1443 and oBB1444 (HindIII-NheI-XbaI) designed to have BglII-compatible 5′ ends at each end were annealed as described previously and ligated to BglII-digested, CIP-treated pT3TS to make pT3TS-linker (pBB231). Colonies were screened for orientation of the linker by colony PCR using T3/oBB1444. The PB transposase coding sequence was amplified from pCMV-PBase plasmid DNA using oBB1445 and oBB1437, which were designed with HindIII restriction site, Xenopus Globin 5′ UTR and BglII, NdeI, SacII and NheI restriction sites or an SpeI restriction site at their 5′ ends, respectively. This PCR product and pBB231 plasmid DNA were digested with HindIII/SpeI and ligated together to make pT3TS-PBase (pBB232).

Linearized and gel purified (Qiagen) pT3TS-SB11 (BamHI) or pT3TS-PBase (XbaI) plasmids were used as template to make 5′-capped SB11 or PBase mRNA, respectively, using the mMessage mMachine High Yield Capped mRNA T3 Transcription Kit (Ambion). mRNA was purified using NucAway Spin columns (Ambion). After determining RNA concentration, samples were aliquoted in 5 µl volumes and stored at −80°C.

Transgenic mice

Prdm16 shRNA containing SB and PB transposon plasmids were digested with PvuII (SB) or PvuII/BspHI (PB) to linearize or remove the plasmid backbone, respectively. Transposon fragments were purified using either the UltraClean GelSpin DNA purification kit (Mol Bio, Carlsbad, CA) or electroelution followed by concentration using the Wizard® DNA Clean-Up System (Promega). Transgenic mice were produced by transgenic injection of each shRNA-expressing transposon plasmid construct along with in vitro transcribed 5′-capped SB11 or PB transposase mRNA into the pronuclei of fertilized eggs [41]. For SB transposon injections plasmid DNA was diluted to 4 µg/ml in injection buffer (5 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 0.1 mM EDTA), and SB mRNA is added to a concentration of 10 µg/ml, aliquoted and stored at −70°C about 2–3 days before injection. For PB transposon injections plasmid DNA was diluted to 1.4–2.0 µg/ml of DNA along with 17, 23, 92 µg/ml or no PBase mRNA in injection buffer. CD-1 females were used as recipients for injected embryos.

All mice were housed in a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle with unlimited access to tap water and Purina 5008 or 5020 chows. All procedures using mice were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals, and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

Foster mother mice were euthanized on E15.5, E16.5 or E17.5 to screen potential transgenic embryos for cleft palate. For each embryo assayed the limbs and tail were collected for genotyping, the head was fixed in 3.7% Formaldehyde in Phosphate Buffered Saline, pH 7 overnight at 4°C, and, for select embryos, the body was stored in RNA Later (Ambion) at −20 C. After fixing, heads were washed and dehydrated through a graded ethanol series to 70% ethanol and stored at −20°C. Genotyping samples were processed as described previously [42]. All embryos were genotyped for the presence of a transgene by PCR using oligonucleotide primers provided in Table S2.

Supporting Information

Detailed summary of transgenic RNAi injections.

(0.11 MB DOC)

Additional oligonucleotide primers.

(0.06 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank David Largaespada and Aron Geurts for sharing SB reagents and technical advice and discourse. Susan M. Faust provided initial phenotype screening. Wanda Fillipiak, Galina Gavrilina, and Maggie Van Keuren of the Transgenic Animal Model Core of the University of Michigan's Biomedical Research Core Facilities participated in the preparation of transgenic mice. We thank Sara McLaughlin and Pablo Hollstein for valuable scientific discussions and reagents.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: Core support was provided by the University of Michigan Cancer Center (National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant CA46592), the University of Michigan Multipurpose Arthritis Center (NIH grant AR20557), the University of Michigan Center for Organogenesis, the University of Michigan Gut Peptide Research Center (NIH grant DK34933), the University of Michigan Nathan Shock Center for the Biology of Aging (NIH grant P30AG013283), and the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (grant 085P1000815). SW Davis and SA Camper were supported by NIH grants R01HD34283 and R37HD30428. BC Bjork was supported by F32HD045066 and K12DE014528. BC Bjork, H Qiu, and DR Beier were supported by RO1HD36404 and R01MH081187. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, et al. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paddison PJ, Caudy AA, Bernstein E, Hannon GJ, Conklin DS. Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) induce sequence-specific silencing in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 2002;16:948–958. doi: 10.1101/gad.981002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen PH, Ambros V. The lin-4 regulatory RNA controls developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans by blocking LIN-14 protein synthesis after the initiation of translation. Dev Biol. 1999;216:671–680. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus MT, Petersen CP, Haines BB, Chen J, Sharp PA. Gene silencing using micro-RNA designed hairpins. Rna. 2002;8:842–850. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202024032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miskey C, Izsvak Z, Kawakami K, Ivics Z. DNA transposons in vertebrate functional genomics. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:629–641. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park F. Lentiviral vectors: are they the future of animal transgenesis? Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:159–173. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00069.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfeifer A, Ikawa M, Dayn Y, Verma IM. Transgenesis by lentiviral vectors: lack of gene silencing in mammalian embryonic stem cells and preimplantation embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2140–2145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251682798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubinson DA, Dillon CP, Kwiatkowski AV, Sievers C, Yang L, et al. A lentivirus-based system to functionally silence genes in primary mammalian cells, stem cells and transgenic mice by RNA interference. Nat Genet. 2003;33:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupuy AJ, Clark K, Carlson CM, Fritz S, Davidson AE, et al. Mammalian germ-line transgenesis by transposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4495–4499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062630599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilber A, Frandsen JL, Geurts JL, Largaespada DA, Hackett PB, et al. RNA as a source of transposase for Sleeping Beauty-mediated gene insertion and expression in somatic cells and tissues. Mol Ther. 2006;13:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding S, Wu X, Li G, Han M, Zhuang Y, et al. Efficient transposition of the piggyBac (PB) transposon in mammalian cells and mice. Cell. 2005;122:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heggestad AD, Notterpek L, Fletcher BS. Transposon-based RNAi delivery system for generating knockdown cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herron BJ, Lu W, Rao C, Liu S, Peters H, et al. Efficient generation and mapping of recessive developmental mutations using ENU mutagenesis. Nat Genet. 2002;30:185–189. doi: 10.1038/ng812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasarskis A, Manova K, Anderson KV. A phenotype-based screen for embryonic lethal mutations in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7485–7490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu Q, Shen Y, Chatterjee B, Siegfried BH, Leatherbury L, et al. ENU induced mutations causing congenital cardiovascular anomalies. Development. 2004;131:6211–6223. doi: 10.1242/dev.01543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarbalis K, May SR, Shen Y, Ekker M, Rubenstein JL, et al. A focused and efficient genetic screening strategy in the mouse: identification of mutations that disrupt cortical development. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sager JJ, Bai Q, Burton EA. Transgenic zebrafish models of neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:285–302. doi: 10.1007/s00429-009-0237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang N, Sun YH, Liu J, Wu G, Su JG, et al. Knock down of gfp and no tail expression in zebrafish embryo by in vivo-transcribed short hairpin RNA with T7 plasmid system. J Biomed Sci. 2007;14:767–776. doi: 10.1007/s11373-007-9189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjork BC, Turbe-Doan A, Prysak M, Herron BJ, Beier DR. Prdm16 is required for normal palatogenesis in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:774–789. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chai Y, Maxson RE., Jr Recent advances in craniofacial morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2353–2375. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson MW. Palate development. Development. 1988;103:41–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.Supplement.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mochizuki N, Shimizu S, Nagasawa T, Tanaka H, Taniwaki M, et al. A novel gene, MEL1, mapped to 1p36.3 is highly homologous to the MDS1/EVI1 gene and is transcriptionally activated in t(1;3)(p36;q21)-positive leukemia cells. Blood. 2000;96:3209–3214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds A, Leake D, Boese Q, Scaringe S, Marshall WS, et al. Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nbt936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandy P, Ventura A, Jacks T. Mammalian RNAi: a practical guide. Biotechniques. 2005;39:215–224. doi: 10.2144/05392RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geurts AM, Yang Y, Clark KJ, Liu G, Cui Z, et al. Gene transfer into genomes of human cells by the sleeping beauty transposon system. Mol Ther. 2003;8:108–117. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park CW, Kren BT, Largaespada DA, Steer CJ. DNA methylation of Sleeping Beauty with transposition into the mouse genome. Genes Cells. 2005;10:763–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yusa K, Takeda J, Horie K. Enhancement of Sleeping Beauty transposition by CpG methylation: possible role of heterochromatin formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4004–4018. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.4004-4018.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makinen PI, Koponen JK, Karkkainen AM, Malm TM, Pulkkinen KH, et al. Stable RNA interference: comparison of U6 and H1 promoters in endothelial cells and in mouse brain. J Gene Med. 2006;8:433–441. doi: 10.1002/jgm.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirilov M, Chai M, van der Hoeven F, Kloz U, Schmid W, et al. Germ line transmission and expression of an RNAi cassette in mice generated by a lentiviral vector system. Transgenic Res. 2007;16:783–793. doi: 10.1007/s11248-007-9119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer O, Tiscornia G, Ikawa M, Verma IM. Rapid generation of knockdown transgenic mice by silencing lentiviral vectors. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:286–292. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dupuy AJ, Akagi K, Largaespada DA, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Mammalian mutagenesis using a highly mobile somatic Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Nature. 2005;436:221–226. doi: 10.1038/nature03691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dupuy AJ, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Sleeping beauty: a novel cancer gene discovery tool. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 1):R75–79. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keng VW, Yae K, Hayakawa T, Mizuno S, Uno Y, et al. Region-specific saturation germline mutagenesis in mice using the Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Nat Methods. 2005;2:763–769. doi: 10.1038/nmeth795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geurts AM, Wilber A, Carlson CM, Lobitz PD, Clark KJ, et al. Conditional gene expression in the mouse using a Sleeping Beauty gene-trap transposon. BMC Biotechnol. 2006;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu SC, Meir YJ, Coates CJ, Handler AM, Pelczar P, et al. piggyBac is a flexible and highly active transposon as compared to sleeping beauty, Tol2, and Mos1 in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15008–15013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606979103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikeda R, Kokubu C, Yusa K, Keng VW, Horie K, et al. Sleeping beauty transposase has an affinity for heterochromatin conformation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1665–1676. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01500-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mates L, Chuah MK, Belay E, Jerchow B, Manoj N, et al. Molecular evolution of a novel hyperactive Sleeping Beauty transposase enables robust stable gene transfer in vertebrates. Nat Genet. 2009;41:753–761. doi: 10.1038/ng.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyatt TM, Ekker SC. Vectors and techniques for ectopic gene expression in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol. 1999;59:117–126. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61823-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagy A, Gertsenstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer R. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2003. Manipulating the mouse embryo: A laboratory manual.764 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed summary of transgenic RNAi injections.

(0.11 MB DOC)

Additional oligonucleotide primers.

(0.06 MB DOC)