Abstract

Apoptosis has been shown to be a significant form of cell loss in many diseases. Detachment of photoreceptors from the retinal pigment epithelium, as seen in various retinal disorders, causes photoreceptor loss and subsequent vision decline. Although caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways are activated after retinal detachment, caspase inhibition by the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD fails to prevent photoreceptor death; thus, we investigated other pathways leading to cell loss. Here, we show that receptor interacting protein (RIP) kinase-mediated necrosis is a significant mode of photoreceptor cell loss in an experimental model of retinal detachment and when caspases are inhibited, RIP-mediated necrosis becomes the predominant form of death. RIP3 expression, a key activator of RIP1 kinase, increased more than 10-fold after retinal detachment. Morphological assessment of detached retinas treated with Z-VAD showed decreased apoptosis but significantly increased necrotic photoreceptor death. RIP1 kinase inhibitor necrostatin-1 or Rip3 deficiency substantially prevented those necrotic changes and reduced oxidative stress and mitochondrial release of apoptosis-inducing factor. Thus, RIP kinase-mediated programmed necrosis is a redundant mechanism of photoreceptor death in addition to apoptosis, and simultaneous inhibition of RIP kinases and caspases is essential for effective neuroprotection and may be a novel therapeutic strategy for treatment of retinal disorders.

Keywords: degenerations, necroptosis

Photoreceptor death and subsequent visual decline occurs when the photoreceptors are separated from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium. Physical separation of photoreceptors is seen in various retinal disorders, including age-related macular degeneration (1), diabetic retinopathy (2), as well as rhegmatogenous (i.e., caused by a break in the retina) retinal detachment (3, 4). Although surgery is carried out to reattach the retina, only two fifths of patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment involving the macula, a region essential for central vision, recover 20/40 or better vision because of photoreceptor death (4, 5). Thus, identification of the mechanisms that underlie photoreceptor death is critical to developing new treatment strategies for these diseases.

Apoptosis and necrosis are two major cell death modalities (6). Apoptosis is a highly regulated process involving the caspase family of cysteine proteases. In contrast, necrosis has been considered a passive, unregulated form of cell death; however, recent evidence indicates that some necrosis can be induced by regulated signal transduction pathways such as those mediated by receptor interacting protein (RIP) kinases, especially in conditions in which caspases are inhibited or cannot be activated efficiently (7, 8). Stimulation of the Fas and TNFR family of death domain receptors is known to mediate apoptosis in most cell types through the activation of the extrinsic caspase pathway. In addition, in certain cells deficient for caspase-8 or treated with the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD, stimulation of death domain receptors causes a RIP1 kinase-dependent programmed necrotic cell death instead of apoptosis (9, 10). This unique mechanism of cell death is termed programmed necrosis or necroptosis (11).

RIP1 is a serine/threonine kinase that contains a death domain and forms a death signaling complex with the Fas-associated death domain and caspase-8 in response to death domain receptor stimulation (12). During death domain receptor-induced apoptosis, RIP1 is cleaved and inactivated by caspase-8, the process of which is prevented by caspase inhibition (13). It has been unclear how RIP1 kinase mediates programmed necrosis, but recent studies revealed that the expression of RIP3 and the RIP1–RIP3 binding through the RIP homotypic interaction motif is a prerequisite for RIP1 kinase activation, leading to reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and necrotic cell death (14–16).

In a rodent model of retinal detachment, we have shown that TNF-α expression levels increase substantially (17) and that caspases are activated after retinal detachment (18, 19). However, caspase inhibition by Z-VAD fails to prevent the retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor death (20). By using a combination of morphological, biochemical, genetic, and pharmacological investigations, the current study demonstrates that programmed necrosis is an essential and redundant mediator of photoreceptor death after retinal detachment. In addition, in the presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD, necrosis becomes the predominant form of photoreceptor cell loss. We further identified RIP kinases as a therapeutic target to prevent photoreceptor loss after retinal detachment.

Result

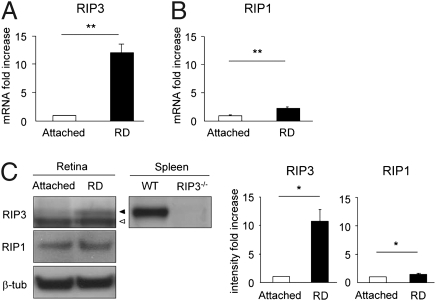

Increased Expression of RIP3 and RIP1 After Retinal Detachment.

RIP3 is a key regulator of RIP1 kinase activation (21), and its expression level has been shown to correlate with responsiveness to programmed necrosis (14). We assessed the expression of RIP3 and RIP1 mRNA in the retina 3 d after retinal detachment by quantitative real-time PCR. This time point was chosen because photoreceptor death peaks at 3 d after retinal detachment (20). RIP3 expression increased 12-fold after retinal detachment compared with that in untreated retina (P = 0.0003; Fig. 1A). RIP1 expression also increased twofold (P = 0.0031; Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis confirmed that RIP3 protein expression increased more than 10-fold after retinal detachment (P = 0.0209; Fig. 1C). In situ hybridization showed that RIP3 signal was detected in neurosensory retina, especially in outer nuclear layer (ONL), after retinal detachment (Fig. S1). These data suggest that RIP-mediated programmed necrosis may be involved in the photoreceptor loss after retinal detachment.

Fig. 1.

Increases in RIP3 and RIP1 expression after retinal detachment. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis for RIP3 (A) and RIP1 (B) in control retina without retinal detachment and in retina 3 d after retinal detachment (n = 9 each); **P < 0.01. (C) Western blot analysis for RIP3 and RIP1 after retinal detachment (n = 4 each). Lane-loading differences were normalized by levels of β-tubulin. For RIP3 analysis, spleen samples from WT and Rip3−/− animals were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Black arrowhead indicates RIP3; white arrowhead indicates nonspecific band. The bar graphs indicate the relative level of RIP3 and RIP1 to β-tubulin by densitometric analysis, reflecting the results from four independent experiments (*P < 0.05).

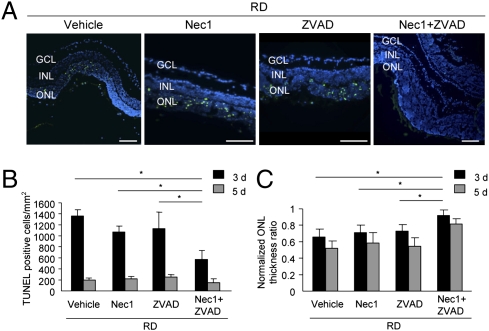

RIP1 Kinase Inhibitor Prevents Retinal Detachment-Induced Photoreceptor Death only in Combination with Caspase Inhibitor.

Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) is a potent and selective inhibitor of programmed necrosis, which targets RIP1 kinase activity (10). RIP1 is phosphorylated at several serine residues in its kinase domain during programmed necrosis and Nec-1 inhibits this phosphorylation (10, 15). To further investigate the role of RIP1 kinase in retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor death, we first assessed the phosphorylation status of RIP1 by immunoprecipitating RIP1 from the retina (Fig. S2A) and then blotting with anti-phosphoserine antibody. Nec-1 (400 μM) and/or Z-VAD (300 μM) were injected subretinally at the time of retinal detachment induction. The dose of compounds was selected based on pilot studies that established that the half-life of the compound is approximately 6 h in the subretinal space. After retinal detachment, RIP1 phosphorylation was elevated especially in Z-VAD-treated retina compared with untreated retina (Fig. S2B). Importantly, Nec-1 plus Z-VAD treatment substantially inhibited this increase of RIP1 phosphorylation (Fig. S2B).

We next examined photoreceptor death by TUNEL 3 d after retinal detachment. Treatment with Nec-1 or Z-VAD alone showed no significant effect on the number of TUNEL-positive cells in ONL (1,067.5 ± 95.5 cells per mm2 and 1,134.7 ± 297.5 cells per mm2, respectively) compared with vehicle treatment (1,366.3 ± 103.7 cells per mm2; Fig. 2 A and B). In comparison, combined treatment with Nec-1 and Z-VAD significantly reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells in ONL (573.1 ± 154.3 cells per mm2; P < 0.05; Fig. 2 A and B). The appearance of TUNEL-positive cells was decreased to approximately 200 cells per mm2 in each group 5 d after retinal detachment (Fig. 2B). Although detection of DNA fragmentation by TUNEL is used as a marker of apoptosis, it has been reported that necrosis, programmed or otherwise, also yields DNA fragments that react with TUNEL in vivo, rendering it difficult to discriminate between apoptosis and necrosis (22). We next measured the thickness ratio of ONL to the total retinal thickness in detached retina compared with normal attached retina. Treatment with Nec-1 or Z-VAD alone had no protective effect on the reduction of ONL thickness ratio, whereas Nec-1 plus Z-VAD treatment significantly prevented the reduction in retinal thickness 3 and 5 d after retinal detachment (P < 0.05; Fig. 2 A and C). More importantly, treatment with Nec-1 plus Z-VAD showed efficient neuroprotection even when these compounds were injected intravitreally 1 d after retinal detachment induction (P < 0.05; Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Nec-1 combined with Z-VAD prevents photoreceptor loss after retinal detachment. (A) TUNEL (green) and DAPI (blue) staining in detached retina treated with vehicle, Nec-1, Z-VAD, or Nec-1 plus Z-VAD on day 3 after retinal detachment. Quantification of TUNEL-positive photoreceptors (B) and ONL thickness ratio (C) on day 3 (vehicle, n = 12; Nec-1, n = 6; Z-VAD, n = 12; Nec-1 plus Z-VAD, n = 12) and day 5 (vehicle, n = 8; Nec-1, n = 6; Z-VAD, n = 8; Nec-1 plus Z-VAD, n = 8) after retinal detachment (*P < 0.05). GCL, ganglion cell layer, INL, inner nuclear layer. (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

To further establish the specificity of RIP1 and caspase inhibitor, we assessed the effect of another necrostatin (Nec-4) (23) and/or pan-caspase inhibitor (PCI) (24) on retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor death. Nec-4 or PCI alone did not show any neuroprotective effect, whereas Nec-4 plus PCI treatment significantly suppressed photoreceptor loss after retinal detachment (P < 0.05; Fig. S4). These data suggest that RIP1 kinase is an important mediator of photoreceptor death after retinal detachment, especially in the presence of pan-caspase inhibitor.

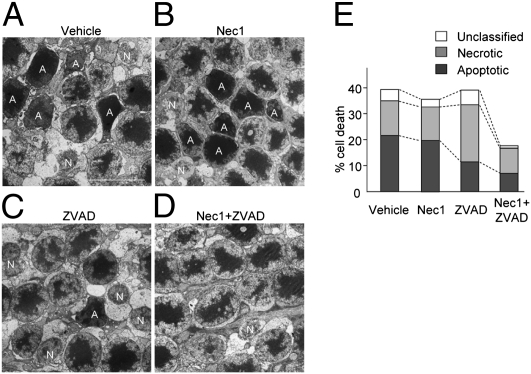

Caspase Inhibition Shifts Retinal Detachment-Induced Photoreceptor Death from Apoptosis to Programmed Necrosis.

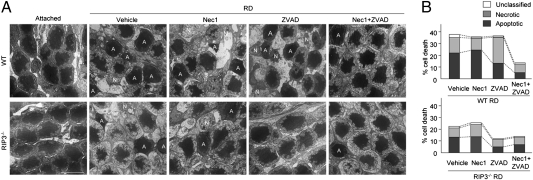

We next examined the morphology of photoreceptors after retinal detachment by transmission EM (TEM) and analyzed the change with Nec-1 and Z-VAD treatment. Photoreceptors showing cellular shrinkage and nuclear condensation were defined as apoptotic cells, whereas photoreceptors associated with cellular and organelle swelling and discontinuities in nuclear and plasma membrane were defined as necrotic cells. The presence of electron-dense granular materials were reported to occur subsequent to both apoptotic and necrotic cell death and cells with these findings were labeled simply as end-stage cell death/unclassified (25, 26). On day 3 after retinal detachment, the photoreceptor death caused by apoptosis was almost twice that caused by necrosis in vehicle-treated retina (21.7 ± 1.3% apoptotic cells, 13.3 ± 1.0% necrotic cells, 4.4 ± 1.4% unclassified; Fig. 3 A and E). Nec-1 treatment did not affect the percentage of apoptotic and necrotic cells after retinal detachment (19.8 ± 2.0% apoptotic cells, 13.1 ± 1.4% necrotic cells, 2.8 ± 0.4% unclassified; Fig. 3 B and E). In comparison, Z-VAD treatment significantly decreased apoptotic photoreceptor death and increased necrotic cell death (11.4 ± 1.2% apoptotic cells, 21.9 ± 2.3% necrotic cells, 5.6 ± 1.4% unclassified; P < 0.05; Fig. 3 C and E). However, Nec-1 combined with Z-VAD substantially prevented the switch to necrotic cell death and led to a decrease in both forms of cell loss (6.9 ± 2.9% apoptotic cells, 9.8 ± 0.7% necrotic cells, 1.0 ± 0.2% unclassified; P < 0.01; Fig. 3 D and E).

Fig. 3.

Involvement of programmed necrosis during retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor death. (A–D) TEM photomicrographs in the ONL on day 3 after retinal detachment in retina treated with vehicle (A), Nec-1 (B), Z-VAD (C), or Nec-1 plus Z-VAD (D). A, apoptotic cell; N, necrotic cell. (E) Quantification of apoptotic and necrotic photoreceptor death after retinal detachment (n = 4 each). Z-VAD treatment increased necrotic cells whereas decreased apoptotic cells (P < 0.05 vs. vehicle). Nec-1 plus Z-VAD significantly suppressed the necrotic cell death (P < 0.01 vs. Z-VAD). (Scale bar, 5 μm.)

Consistent with the EM findings, subretinal injection of propidium iodide (PI) before enucleation, a technique to demonstrate cells with disrupted cell membrane (27), showed increased number of PI-positive photoreceptors in Z-VAD-treated retina compared with vehicle-treated retina 3 d after retinal detachment (P < 0.05; Fig. S5 A and B). Treatment with Nec-1 plus Z-VAD significantly suppressed the number of PI-positive cells in ONL (P < 0.05; Fig. S5 A and B).

Collectively, these data indicate that necrosis as well as apoptosis is involved in photoreceptor death after retinal detachment, and that RIP1 kinase-mediated necrosis becomes a predominant form of the photoreceptor death when caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway is inhibited.

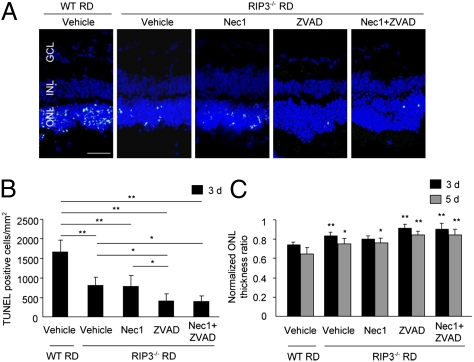

Rip3 Deficiency Inhibits Induction of Programmed Necrosis and Prevents Photoreceptor Death After Retinal Detachment.

To analyze further the role of RIP kinases in retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor death, we caused retinal detachment in mice deficient for Rip3, a key regulator of RIP1 kinase activation (21). Without retinal detachment, the morphology of retina and ONL thickness ratio were similar in Rip3−/− and WT mice. Three days after retinal detachment, Rip3−/− mice showed significantly fewer TUNEL-positive cells (804.7 ± 204.5 cells per mm2) than WT mice (1,668.7 ± 305.8 cells per mm2; P < 0.01; Fig. 4 A and B). In contrast to WT animals, Z-VAD treatment in Rip3−/− mice further decreased TUNEL-positive cells after retinal detachment (407.7 ± 188.9 cells per mm2; P < 0.05 vs. Rip3−/− mice with vehicle), whereas Nec-1 did not provide any additional effect (786.7 ± 278.7 cells per mm2; Fig. 4 A and B). Rip3−/− retinas exhibited preserved ONL thickness ratio, which was augmented by Z-VAD treatment, on days 3 and 5 after retinal detachment (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Rip3 deficiency provides neuroprotection after retinal detachment that is augmented by Z-VAD. (A) TUNEL (green) and DAPI (blue) staining in WT and Rip3−/− retina treated with vehicle, Nec-1, Z-VAD, or Nec-1 plus Z-VAD on day 3 after retinal detachment. Quantification of TUNEL-positive photoreceptors (B) and ONL thickness ratio (C) on day 3 (WT vehicle, n = 6; Rip3−/− vehicle, n = 7; Rip3−/− Nec-1, n = 8; Rip3−/− Z-VAD, n = 7; Rip3−/− Nec-1 plus Z-VAD, n = 6) and day 5 (WT vehicle, n = 7; Rip3−/− vehicle, n = 6; Rip3−/− Nec-1, n = 6; Rip3−/− Z-VAD, n = 6; Rip3−/− Nec-1 plus Z-VAD, n = 6) after retinal detachment (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

We next performed morphological assessment of the Rip3−/− retina after retinal detachment by TEM. In WT mice, the percentage of necrotic photoreceptors was significantly increased by Z-VAD treatment (13.3 ± 1.5% apoptotic cells, 22.1 ± 1.0% necrotic cells, 1.0 ± 0.6% unclassified) compared with vehicle treatment (22.2 ± 4.0% apoptotic cells, 13.0 ± 2.1% necrotic cells, 2.5 ± 1.3% unclassified; P < 0.05; Fig. 5 A and B). In contrast, in Rip3−/− mice, Z-VAD treatment substantially prevented photoreceptor death after retinal detachment without inducing necrotic cell death (4.8 ± 1.3% apoptotic cells, 6.4 ± 1.3% necrotic cells, 0.9 ± 0.4% unclassified). Consistent with these results, the number of photoreceptors with disrupted plasma membrane, as assessed by in vivo PI labeling, was not increased by Z-VAD treatment in Rip3−/− retinas (Fig. S5 C and D), confirming that RIP3 plays an essential role to induce programmed necrosis after retinal detachment, especially in the presence of caspase inhibitor. In addition, unexpectedly, Rip3−/− retinas showed fewer apoptotic cells after retinal detachment (13.4 ± 1.1% apoptotic cells, 8.1 ± 1.0% necrotic cells, 1.2 ± 0.5% unclassified) compared with WT retinas, suggesting that RIP3 may be involved not only in RIP1-mediated programmed necrosis but also in other cell death pathways. Alternatively, the kinetics of a single administration of Nec-1 to inhibit RIP1 kinase are different from the chronic loss of RIP kinase activity in Rip3−/− animals.

Fig. 5.

Rip3 deficiency inhibits induction of programmed necrosis and prevents photoreceptor death after retinal detachment. (A) TEM photomicrographs in the ONL on day 3 after retinal detachment in WT and Rip3−/− retina treated with vehicle, Nec-1, Z-VAD, or Nec-1 plus Z-VAD. In untreated attached retina, the retinal morphology was similar in WT and Rip3−/− mice. A, apoptotic cell; N, necrotic cell. (B) Quantification of apoptotic and necrotic photoreceptor death after retinal detachment (n = 4 each). Rip3 deficiency inhibits the switch to necrotic cell death by Z-VAD treatment and prevents photoreceptor death after retinal detachment. (Scale bar, 5 μm.)

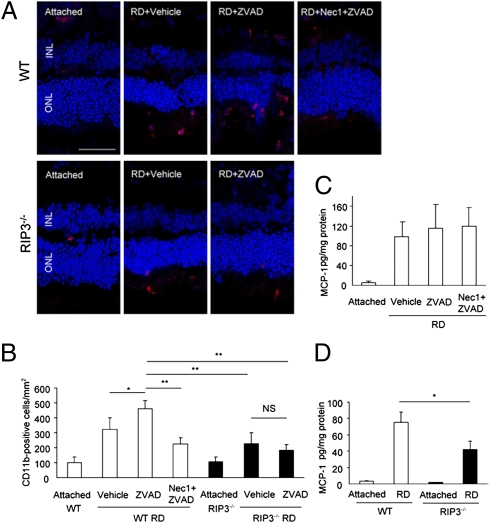

As the release of intracellular content in necrosis results in secondary inflammation, we next analyzed the inflammatory reaction after retinal detachment by immunofluorescence detection of the macrophage/microglial marker CD11b. On day 3 after retinal detachment, Z-VAD-treated eyes demonstrated greater infiltration of CD11b-positive cells in the detached retina compared with vehicle-treated eyes (P < 0.05; Fig. 6 A and B), suggesting that necrotic cell death may promote inflammatory reaction. This increase of CD11b-positive cells by Z-VAD was significantly suppressed with Nec-1 plus Z-VAD treatment or Rip3 deficiency (P < 0.01; Fig. 6 A and B). We previously described that monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) is an essential mediator of early infiltration of macrophage/microglia and the subsequent cell death after retinal detachment (28). However, Nec-1 plus Z-VAD did not affect MCP-1 expression (Fig. 6C). Rip3−/− retinas also showed substantial up-regulation of MCP-1 after retinal detachment, although its expression level was slightly decreased compared with WT retinas (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Effect of RIP pathways on inflammatory response after retinal detachment. (A and B) Immunofluorescence for CD11b (A) and quantification of CD11b-positive macrophage/microglia in WT and Rip3−/− retina after retinal detachment. In WT mice, Z-VAD treatment significantly increased infiltration of CD11b-positive cells compared with vehicle treatment (P < 0.05). This increase of CD11b-positive cells was significantly suppressed with Nec-1 plus Z-VAD treatment or Rip3 deficiency (P < 0.01). (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (C and D) ELISA for MCP-1 on day 3 after retinal detachment in retina treated with vehicle (n = 5), Z-VAD (n = 5), or Nec-1 plus Z-VAD (n = 6) (C) and in WT and Rip3−/− retina (n = 5 each) (D). The retinas without retinal detachment were used as controls. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; NS, not significant.

RIP Kinases Mediate ROS Production and Apoptosis-Inducing Factor Nuclear Translocation After Retinal Detachment.

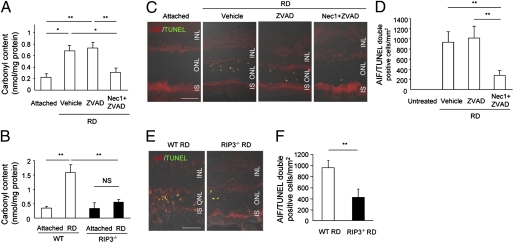

Recent studies reported that RIP kinases regulate downstream ROS production during programmed necrosis (15, 16, 29). To examine the oxidative retinal damage following retinal detachment, we used ELISA for carbonyl adducts of proteins. On day 3 after retinal detachment, the retina treated with vehicle or Z-VAD exhibited significant increase of carbonyl contents compared with untreated retina (P < 0.05; Fig. 7A). In contrast, Nec-1 plus Z-VAD treatment almost completely suppressed the increase of carbonyl contents after retinal detachment (P < 0.05; Fig. 7A). Rip3−/− retinas also showed significantly less carbonyl contents after retinal detachment compared with WT retinas (P < 0.01; Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

RIP kinase inhibition prevents ROS production and AIF nuclear translocation after retinal detachment. (A and B) ELISA to detect carbonyl contents on day 3 after retinal detachment in retina treated with vehicle, Z-VAD or Nec-1 plus Z-VAD (n = 7 each) (A) and in WT and Rip3−/− retina (n = 10 each) (B). The retinas without retinal detachment were used as controls (n = 6–8). Double staining for AIF and TUNEL (C and E) and quantification of AIF/TUNEL double-positive photoreceptors (D and F) on day 3 after retinal detachment in retina treated with vehicle, Z-VAD, or Nec-1 plus Z-VAD (n = 6 each; C and D) and in WT and Rip3−/− retina (n = 5 each; E and F). IS, inner segment. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) is a caspase-independent inducer of cell death, which is released from the mitochondria and translocates into the nuclei during cell death (30). We previously described that mitochondrial release of AIF is a critical event for the photoreceptor death after retinal detachment (20, 31). Because ROS overproduction is known to induce mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and AIF release (32), we next examined the cellular localization of AIF by immunofluorescence. AIF translocation into TUNEL-positive photoreceptor nuclei was increased after retinal detachment; whereas Nec-1 plus Z-VAD treatment or Rip3 deficiency substantially reduced AIF nuclear translocation (P < 0.01; Fig. 7 C–F). These data demonstrate that ROS production and AIF nuclear translocation are downstream events of RIP signaling.

Discussion

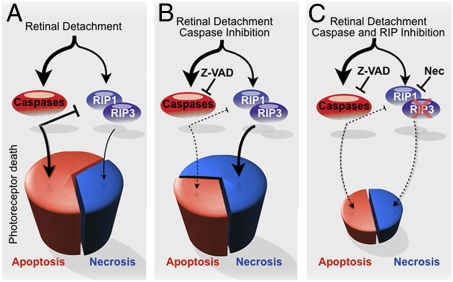

Photoreceptor death after retinal detachment has been thought to be caused mainly by apoptosis (3, 4). Although caspase-dependent pathway is known to be activated after retinal detachment, caspase inhibition by pan-caspase inhibitor fails to prevent photoreceptor death (18, 20). In this study, we investigated other pathways leading to photoreceptor death, and demonstrated that necrotic photoreceptor death occurs after retinal detachment, although its frequency is approximately half that of apoptosis. Consistent with our findings, Arimura et al. showed that the vitreous level of high-mobility group box1 protein, which is known to be released from necrotic cells but not apoptotic cells, is increased in human eyes with retinal detachment (33, 34). Furthermore, we found that Z-VAD treatment decreases apoptosis but increases necrotic photoreceptor death after retinal detachment, and that Nec-1 cotreatment effectively suppresses necrotic photoreceptor death. These findings clearly demonstrate programmed necrosis as an essential and complementary mechanism of photoreceptor death, which is further revealed when caspases are inhibited (Fig. 8). In other retinal degenerative conditions such as inherited retinal degeneration and light-induced retinal injury, it has been shown that the photoreceptor death is not prevented by Z-VAD (35–37), and thus it may be possible that programmed necrosis may underlie the death execution in these diseases as well.

Fig. 8.

Proposed mechanism of photoreceptor loss after retinal detachment. (A) After retinal detachment, photoreceptor death is caused mainly by apoptosis. (B) Caspase inhibition by Z-VAD decreases apoptosis but promotes RIP-mediated programmed necrosis. (C) Blockade of both caspases and RIP kinases is essential for effective prevention of photoreceptor loss.

RIP1 is an adaptor kinase that acts downstream of death domain receptors and is essential for both cell survival and death (38). The kinase activity of RIP1 is crucial for programmed necrosis, but dispensable for prosurvival NF-κB activation (9, 10, 39). Consistent with these results, Nec-1 inhibited RIP1 phosphorylation, which was increased by Z-VAD after retinal detachment, but showed no effect on NF-κB p65 phosphorylation (Fig. S6). RIP1 switches function to a regulator of cell death when it is unubiquitinated and forms a death signaling complex (40, 41). In addition, recent studies revealed that formation of RIP1–RIP3 complex is a critical step in the RIP1 kinase activation and induction of programmed necrosis (14–16). After retinal detachment, RIP3 expression increased more than 10-fold and Rip3 deficiency prevented the shift to necrotic photoreceptor death by Z-VAD, implying that RIP3 is a key regulator of programmed necrosis after retinal detachment.

TNF-α and Fas-L are potent inducer of programmed necrosis as well as apoptosis (11). After retinal detachment, TNF-α was increased in detached retina (Fig. S7 A and B) and treatment with neutralizing anti–TNF-α antibody suppressed photoreceptor loss (Fig. S7 C and D), suggesting that TNF-α may contribute to the induction of apoptosis and programmed necrosis. In addition to TNF-α, Fas-L/Fas pathway is known to be activated and mediate photoreceptor death after retinal detachment (19, 42), and may cooperate with TNF-α to activate RIP kinases and promote programmed necrosis in addition to apoptosis. Thus, RIP kinases act as common intermediaries for various upstream death signals and their blockade in addition to caspases is likely necessary for effective neuroprotection (Fig. S8).

Overproduction of ROS has been implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction and programmed necrosis (43, 44). NADPH oxidase 1 forms a complex with RIP1 and generates superoxide during programmed necrosis (29). Alternatively, RIP3 activates metabolic enzymes such as glutamate dehydrogenase 1, and thereby increases mitochondrial ROS production (16). Consistent with these reports, ROS production after retinal detachment was suppressed by RIP kinase inhibition. In addition, our data show that RIP kinases act upstream of AIF nuclear translocation. Recent studies demonstrate that AIF is an essential mediator of programmed necrosis induced by alkylating DNA damage (45). These results link RIP kinases, AIF translocation, and programmed necrosis.

Cell death and inflammation communicate with each other during neurodegeneration (46). Infiltrating inflammatory cells stimulate neuronal cell death (28), and conversely dying cells, especially of the necrotic form, trigger inflammation (47). We previously described that MCP-1 is a key mediator of early infiltration of macrophage/microglia after retinal detachment (28). However, MCP-1 up-regulation after retinal detachment was not substantially altered by Nec-1 plus Z-VAD or Rip3 deficiency, suggesting that RIP kinases are not involved in the initiation of inflammation. Our in situ hybridization data suggest that RIP3 is detected in ONL after retinal detachment, suggesting that RIP kinase inhibition may target photoreceptors and suppress inflammation subsequent to photoreceptor death. However, as RIP3 is known to be expressed in several cell types including macrophages (48), and given the limited resolution of our in situ hybridization, we cannot exclude the possibility that RIP kinase inhibition may affect macrophage/microglia function; defining the role of RIP kinases in cell death and inflammation warrants further studies using tissue-specific Rip3 knockouts.

Photoreceptor loss occurs acutely after retinal detachment, and the visual acuity of patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is not always restored after successful reattachment surgery. In other retinal disorders—including the most and second-most common causes of blindness in the adults of the western world, age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy—detachment of retinal photoreceptors persists chronically and vision loss progresses. Thus, neuroprotective agents preventing photoreceptor loss may open a novel therapeutic approach to the treatment of these diseases. Unfortunately, most promises of neuroprotection have not come to clinical fruition, likely because most of the work on this field has been focused on monotherapy. In this work, we identify RIP-mediated programmed necrosis as an essential pathway for cell loss, which acts in concert with caspase-dependent apoptosis. Simultaneous inhibition of both RIP1 kinase and caspase pathways with small molecule compounds provides significant protection of photoreceptors after photoreceptor detachment and may be used as a therapeutic strategy for preventing vision deficit in various retinal disorders associated with photoreceptor loss.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Reagents.

All animal experiments adhered to the statement of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, and protocols were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. Adult male Brown Norway rats and WT C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River. Rip3−/− mice were provided from D. M. Dixit (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) and backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice (48). Nec-1 was provided by J. Yuan (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Z-VAD was purchased from Alexis.

Induction of Retinal Detachment, TUNEL, and Evaluation of ONL Thickness Ratio.

Experimental retinal detachment was induced as previously described (20). TUNEL and quantification of TUNEL-positive cells in ONL were performed as previously described (28). The ratio of ONL thickness to the total retinal thickness was determined by ImageJ software and standardized by that in the attached retina. Five sections were randomly selected in each eye, and the central area of detached retina and the midperipheral region of attached retina were photographed. Then, the ONL thickness ratio was measured at 10 points in each section by masked observers. The data are expressed as normalized ONL thickness ratio: [(ONL / neuroretina thickness in detached retina) / (ONL / neuroretina thickness in attached retina)].

Statistical Analysis.

All values were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences between two groups were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test. Multiple group comparison was performed by ANOVA followed by Tukey–Kramer adjustments. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. A detailed description of methods is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Michaud (Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary) and F. Morikawa (Kyushu University) for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Bacardi Fund (D.G.V.), the Research to Prevent Blindness Foundation (D.G.V.), the Lions Eye Research Fund (D.G.V.), the Onassis Foundation (D.G.V.), a grant-in-aid from Fight For Sight (D.G.V.), the Harvard Ophthalmology Department (D.G.V.), a Vitreoretinal Fellowship from Bausch and Lomb (to Y. Morizane), and National Eye Institute Grant EY014104 (Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary core grant).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: G.T. and D.G.V. have a provisional patent filling.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1009179107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dunaief JL, Dentchev T, Ying GS, Milam AH. The role of apoptosis in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1435–1442. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.11.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber AJ, et al. Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Early onset and effect of insulin. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:783–791. doi: 10.1172/JCI2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook B, Lewis GP, Fisher SK, Adler R. Apoptotic photoreceptor degeneration in experimental retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:990–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arroyo JG, Yang L, Bula D, Chen DF. Photoreceptor apoptosis in human retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:605–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campo RV, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy without scleral buckle for pseudophakic retinal detachments. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1811–1815. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroemer G, et al. Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Classification of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:3–11. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golstein P, Kroemer G. Cell death by necrosis: Towards a molecular definition. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Festjens N, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Necrosis, a well-orchestrated form of cell demise: Signalling cascades, important mediators and concomitant immune response. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1371–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holler N, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:489–495. doi: 10.1038/82732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Degterev A, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degterev A, et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Festjens N, Vanden Berghe T, Cornelis S, Vandenabeele P. RIP1, a kinase on the crossroads of a cell's decision to live or die. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:400–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Y, Devin A, Rodriguez Y, Liu ZG. Cleavage of the death domain kinase RIP by caspase-8 prompts TNF-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2514–2526. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He S, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YS, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang DW, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325:332–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakazawa T, et al. Characterization of cytokine responses to retinal detachment in rats. Mol Vis. 2006;12:867–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zacks DN, et al. Caspase activation in an experimental model of retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1262–1267. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zacks DN, Zheng QD, Han Y, Bakhru R, Miller JW. FAS-mediated apoptosis and its relation to intrinsic pathway activation in an experimental model of retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4563–4569. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hisatomi T, et al. Relocalization of apoptosis-inducing factor in photoreceptor apoptosis induced by retinal detachment in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64078-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. RIP kinases initiate programmed necrosis. J Mol Cell Biol. 2009;1:8–10. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grasl-Kraupp B, et al. In situ detection of fragmented DNA (TUNEL assay) fails to discriminate among apoptosis, necrosis, and autolytic cell death: A cautionary note. Hepatology. 1995;21:1465–1468. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840210534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng X, et al. Structure-activity relationship study of [1,2,3]thiadiazole necroptosis inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:6836–6840. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoglen NC, et al. Characterization of IDN-6556 (3-[2-(2-tert-butyl-phenylaminooxalyl)-amino]-propionylamino]-4-oxo-5-(2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-phenoxy)-pentanoic acid): A liver-targeted caspase inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:634–640. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hisatomi T, et al. Clearance of apoptotic photoreceptors: Elimination of apoptotic debris into the subretinal space and macrophage-mediated phagocytosis via phosphatidylserine receptor and integrin alphavbeta3. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erickson PA, Fisher SK, Anderson DH, Stern WH, Borgula GA. Retinal detachment in the cat: The outer nuclear and outer plexiform layers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983;24:927–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.You Z, et al. Necrostatin-1 reduces histopathology and improves functional outcome after controlled cortical impact in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1564–1573. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakazawa T, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 mediates retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2425–2430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608167104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim YS, Morgan MJ, Choksi S, Liu ZG. TNF-induced activation of the Nox1 NADPH oxidase and its role in the induction of necrotic cell death. Mol Cell. 2007;26:675–687. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Susin SA, et al. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hisatomi T, et al. HIV protease inhibitors provide neuroprotection through inhibition of mitochondrial apoptosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2025–2038. doi: 10.1172/JCI34267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krantic S, Mechawar N, Reix S, Quirion R. Apoptosis-inducing factor: A matter of neuron life and death. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81:179–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arimura N, et al. Intraocular expression and release of high-mobility group box 1 protein in retinal detachment. Lab Invest. 2009;89:278–289. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donovan M, Cotter TG. Caspase-independent photoreceptor apoptosis in vivo and differential expression of apoptotic protease activating factor-1 and caspase-3 during retinal development. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1220–1231. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanges D, Comitato A, Tammaro R, Marigo V. Apoptosis in retinal degeneration involves cross-talk between apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and caspase-12 and is blocked by calpain inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17366–17371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606276103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murakami Y, et al. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor is an essential mechanism of the neuroprotective activity of pigment epithelium-derived factor in a rat model of retinal degeneration. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1326–1338. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Van Herreweghe F, Vanden Berghe T. The role of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3 in TNF-induced necrosis. Sci Signal. 2010;3:re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3115re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee TH, Shank J, Cusson N, Kelliher MA. The kinase activity of Rip1 is not required for tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced IkappaB kinase or p38 MAP kinase activation or for the ubiquitination of Rip1 by Traf2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33185–33191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahoney DJ, et al. Both cIAP1 and cIAP2 regulate TNFalpha-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11778–11783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711122105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Du F, Wang X. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 2008;133:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zacks DN, Boehlke C, Richards AL, Zheng QD. Role of the Fas-signaling pathway in photoreceptor neuroprotection. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1389–1395. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.10.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vercammen D, et al. Dual signaling of the Fas receptor: Initiation of both apoptotic and necrotic cell death pathways. J Exp Med. 1998;188:919–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin Y, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-induced nonapoptotic cell death requires receptor-interacting protein-mediated cellular reactive oxygen species accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10822–10828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moubarak RS, et al. Sequential activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, calpains, and Bax is essential in apoptosis-inducing factor-mediated programmed necrosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4844–4862. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02141-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zitvogel L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Decoding cell death signals in inflammation and immunity. Cell. 2010;140:798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavassani KA, et al. TLR3 is an endogenous sensor of tissue necrosis during acute inflammatory events. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2609–2621. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newton K, Sun X, Dixit VM. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1464–1469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1464-1469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.