Abstract

The GluA4-containing Ca2+-permeable α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid receptors (Ca-AMPARs) were previously shown to mediate excitotoxicity through mechanisms involving the activator protein-1 (AP-1), a c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) substrate. To further investigate JNK involvement in excitotoxic pathways coupled to Ca-AMPARs we used HEK293 cells expressing GluA4-containing Ca-AMPARs (HEK-GluA4). Cell death induced by overstimulation of Ca-AMPARs was mediated, at least in part, by JNK. Importantly, JNK activation downstream of these receptors was dependent on the extracellular Ca2+ concentration. In our quest for a molecular link between Ca-AMPARs and the JNK pathway we found that the JNK interacting protein-1 (JIP-1) interacts with the GluA4 subunit of AMPARs through the N-terminal domain. In vivo, the excitotoxin kainate promoted the association between GluA4 and JIP-1 in the rat hippocampus. Taken together, our results show that the JNK pathway is activated by Ca-AMPARs upon excitotoxic stimulation and suggest that JIP-1 may contribute to the propagation of the excitotoxic signal.

Keywords: AMPA receptors, AP-1 transcription factor, Calcium channels, Cell death, Excitotoxicity, Transient global ischemia, JNK

Introduction

In several neurological diseases glutamate accumulates in the extracellular space, overactivating glutamate receptors and inducing excitotoxic cell death. Although the signalling pathways triggered by excitotoxic stimuli are not completely understood, Ca2+ overload is considered to be a key factor contributing to cell death (Arundine and Tymianski, 2003; Kwak and Weiss, 2006; Forder and Tymianski, 2009). The Ca2+-permeable α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid receptors (Ca-AMPARs) have been increasingly associated with mechanisms of selective neuronal death due to excessive Ca2+/Zn2+ entry through the receptor channel (Gorter et al., 1997; Pellegrini-Giampietro et al., 1997; Weiss and Sensi, 2000; Weiss et al., 2000; Cull-Candy et al., 2006; Kwak and Weiss, 2006; Liu and Zukin, 2007; Buckingham et al., 2008). AMPARs are tetrameric structures assembled from GluA1–4 subunits. The Ca2+ permeability of these receptors is dictated by the presence of GluA2 subunits, which undergo RNA editing, resulting in a glutamine (Q) to arginine (R) switch at the ‘Q/R site’ in the pore-lining region of the receptor, rendering GluA2-containing AMPARs Ca2+-impermeable (Seeburg and Hartner, 2003; Cull-Candy et al., 2006; Liu and Zukin, 2007). Although AMPARs in the hippocampus are mainly Ca2+-impermeable, transient cerebral global ischemia primes Ca-AMPAR expression in CA1 hippocampal neurons due to a decrease in GluA2 gene expression (Gorter et al., 1997; Calderone et al., 2003; Noh et al., 2005) and in GluA2 RNA editing (Peng et al., 2006), which contributes to the selective death of these neurons. However, other studies point to a lack of correlation between Ca-AMPARs and selective neuronal death (Hof et al., 1998; Kjoller and Diemer, 2000) and, in mutant mice, not all the changes in the GluA2 subunit correlate with Ca2+-triggered neuronal death (Feldmeyer et al., 1999). Thus, neuronal vulnerability to Ca2+ toxicity mediated by Ca-AMPARs is probably the result of an interplay of factors such as the kinetics of receptor desensitization, the Ca2+ buffering mechanisms, and the distribution of Ca-AMPARs in the cell, as well as possible maturational aspects of that subpopulation (Friedman, 2006).

We previously identified the activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor as a target of a cell death signalling cascade induced by overactivation of GluA4-contaning Ca-AMPARs (Santos et al., 2006). AP-1 is a transcription factor sensitive to stress conditions and induced by several stimuli, including glutamatergic stimulation. This transcription factor exists as homo- or heterodimers of proteins of the Jun and Fos families. The former group includes c-Jun, the most potent activator of AP-1-mediated gene transcription (Raivich and Behrens, 2006). c-Jun activity is regulated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-dependent phosphorylation and several evidences show that the JNK/c-Jun signalling pathway is important for neuronal death induced by ischemia and other excitotoxic stimuli (Behrens et al., 1999; Borsello et al., 2003; Kuan et al., 2003; Brecht et al., 2005; Guan et al., 2005; Esneault et al., 2008). However, little is known on how the signalling cascade leading to JNK/c-Jun activation is organized under excitotoxic conditions.

JNKs belong to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) superfamily, and the components of these pathways are assembled into signalling complexes by scaffold proteins that improve co-localization and regulate the signalling cascade activation (Kukekov et al., 2006; Whitmarsh, 2006; Cui et al., 2007; Weston and Davis, 2007). Among the MAPK scaffold proteins, the members of the JNK interacting protein (JIP) family are known to form complexes with specific JNK and p38 signalling modules, and have an important role in several cellular functions (Whitmarsh, 2006). Noteworthy, Jip-1 gene disruption prevents the activation of JNK induced by excitotoxic and anoxic stress in vivo and in vitro (Whitmarsh et al., 2001).

In this work, we investigated whether overstimulation of GluA4-containing Ca-AMPARs is coupled to the JNK signalling pathway and putative molecular partners bringing JNK signalling complexes into the vicinity of AMPARs. For this purpose we used a human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cell line constitutively expressing the GluA4flip subunit of AMPARs (HEK-GluA4) (Iizuka et al., 2000). HEK-GluA4 cells were stimulated with glutamate plus CTZ, a protocol that causes Ca-AMPAR-mediated cell death (Santos et al., 2006). CTZ, an allosteric modulator of AMPARs, strongly attenuates desensitization of the receptor (Mayer, 2006), allowing the study of Ca-AMPAR-mediated toxicity under experimental conditions similar to those observed in several pathological situations, where the molecular structure of AMPARs is altered, leading to an increase in Ca2+ permeability (Gorter et al., 1997; Kawahara et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2004; Noh et al., 2005; Peng et al., 2006) or a slower desensitization kinetics (Tomiyama et al., 2002). We show that Ca-AMPAR overstimulation evokes JNK activation in a Ca2+-dependent manner which mediates, at least in part, HEK-GluA4 cell death. Moreover, in vivo studies using the kainate (KA) model of excitotoxicity (i.p. injection) suggest that JIP-1 might regulate the propagation of excitotoxic signals mediated by AMPARs since JIP-1 can interact with GluA4 through its N-terminal domain.

Experimental procedures

Materials

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and geneticin (G418) were purchased from Gibco, Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, California, USA). The BCA assay kit was purchased from Pierce, as part of Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, Illinois, USA). 6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione disodium (CNQX) and cyclothiazide (CTZ) were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Lipofectamine™ Reagent, Lipofectamine™2000 Reagent and OptiMEM were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Protein A sepharose CL-4B was obtained from GE Healthcare (Uppsala, Sweden). The QuikChange® II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit was bought from Stratagene (La Jolla, California, USA). SB203580, a p38 inhibitor, was obtained from Calbiochem, EMD Chemicals Inc., an affiliate of Merck (Darmstad, Germany). Kainic acid was purchased from Ascent Scientific (North Sommerset, UK). CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive assay kit was purchased from Promega (Madison, Wisconsin). The antibodies for phospho-SAPK/JNK (T183/Y185) (#4671) and phospho-c-Jun (Ser63) (#9261) were purchased from Cell Signalling Technology (Boston, Massachusetts, USA). Normal rabbit IgGs and the antibody for c-Jun/AP-1 (sc-45-G) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, California, USA). The antibody against the Flag epitope (F7425) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and the antibodies for JIP-1 (AF4366) and pan JNK (MAB1387) were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). The antibodies against phospho-GluA4 (T855), GluA4 and GluA4 IgGs, used for immunoprecipitation assays, were generous gifts from R. L. Huganir (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Baltimore, Maryland, USA). All other reagents used in this work were from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) or from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Plasmid constructions

The pcDNA3-Flag-JIP-1, encoding the DNA from mouse JIP-1a attached to the Flag epitope (Dickens et al., 1997), the pc-DNA3.1-Flag-JBD construct, encoding the amino acid residues 127–282 from JIP-1 mouse protein attached to Flag epitope, the constructs used to map the interaction between JIP-1 and GluA4 (pEBG-JIP-1 [1–282], pEBG-JIP-1 [471–660], pEBG-JIP-1 [283–660], pEBG-JIP-1 ΔJBD, lacking amino acids 127–282, and pEBG-JIP-1 [1–660]) and the pcDNA3.1 plasmid were obtained from R.J. Davis, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts, USA. The construct pEBG-GST was used as a negative control in the GST pull-down assays. The pcDNA1-Flag construct, used as control of transfection, was a gift from J. Ham, University College London, London, UK. The pcDNA3.1-Flag-GluA4 construct was from K. Keinänen, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. Point mutations were introduced in this construction, using QuikChange® II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, in order to mutate the JNK phosphorylation site on GluA4 (T855). The primers 5′-GGAGAAAACGGCCGTGTGCTGGCCCCTGACTGCCCCAAGGCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCCTTGGGGCAGTCAGGGGCCAGCACACGGCCGTTTTCTCC-3′ (reverse) were used to mutate T855 to an alanine residue, which is a non-phosphorylatable mutant (GluA4 T855A). A phosphomimetic mutant was also prepared (GluA4 T855D) using the following primers, 5′-GGAGAAAACGGCCGTGTGCTGGACCCTGACTGCCCCAAGGCC-3′ (forward), and 5′-GGCCTTGGGGCAGTCAGGGTCCAGCACACGGCCG-TTTTCTCC-3′ (reverse).

Culture and transfection of HEK-GluA4 cells

HEK293 cells stably transfected with the human GluA4flip subunit of AMPARs were cultured in DMEM with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, in the presence of G418 to select cells expressing the GluA4 clone (Iizuka et al., 2000), and kept at 37 °C, in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2/95% air. This cell line was a generous gift from M. Iizuka and E. Barsoumian, Kawanishi Pharma Research Institute (Kawanishi, Japan). Before transfection HEK-GluA4 cells (0.5×105 cells/cm2) were cultured for 24 h in antibiotic-free DMEM in poly-D-lysine (0.1 mg/ml) coated Petri dishes. Transfections were carried out with Lipofectamine™ Reagent, OptiMEM and 0.15 μg DNA/cm2, for 3 h at 37 °C. Then, cells were transferred to the conditioned medium, placed in the incubator at 37 °C and subjected to excitotoxic stimulation 36–40 h later. Alternatively, for the transient expression experiments in HEK293A cells, we used the Lipofectamine™ 2000 Reagent. Cells were cultured with a density of 0.27×105 cells/cm2, 1 day prior to transfection, which was performed overnight, in the presence of OptiMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

Excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells

Excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells was performed as previously described (Santos et al., 2006). Briefly, at the second day in vitro, subconfluent cultures of HEK-GluA4 cells were stimulated, for the indicated period of time, with 100 μM–1 mM glutamate, in the presence of 100 μM CTZ, in sodium buffer (132 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 6 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2.5 mM CaCl2), at 37 °C. A pre-incubation of 5 min with CTZ and CNQX was performed whenever these drugs were used. In the experiments in which SB203580 was present, a pre-incubation period of 2 h was performed and the inhibitor was also present during stimulation and post-stimulation periods. Control cells were placed in sodium buffer without drugs. Excitotoxic stimulation of HEK293A cells transfected with the GluA4 constructs was performed similarly. To investigate Ca2+-dependent events, stimulation with glutamate was performed in sodium buffer with 0–2.5 mM Ca2+.

Cell viability assay

After excitotoxic stimulation the cells were washed, and further incubated in serum- and G418-free DMEM supplemented with CaCl2 (final concentration 2.5 mM), and kept at 37 °C in the incubator for 24 h. The metabolic activity of HEK-GluA4 cells was then evaluated by a colorimetric assay using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT). Incubation with MTT (0.5 mg/ml in sodium buffer with 1 mM CaCl2) was performed for 45 min (24 well plates) or 2 h (48 well plates), at 37 °C in the incubator. Formazan crystals were dissolved in 0.04 M HCl in isopropanol and colorimetrically quantitated (absorbance at 570 nm). All experiments were carried out in triplicate, for each independent experiment, and the reduction of MTT was expressed as percentage of the absorbance value obtained in the control cultures which was considered 100%.

Cytotoxicity assay

After excitotoxic stimulation the cells were washed and returned to the incubator for 24 h in serum-free DMEM supplemented with CaCl2 (final concentration 2.5 mM). The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage to the extracellular medium was then evaluated by a colorimetric assay, using CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive assay kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The percentage of LDH was determined as the ratio between LDH activity in the extracellular medium and total LDH activity. All experiments were carried out in triplicate, for each independent experiment, and the LDH activity was normalised to the control (with Ca2+), which was considered as 1.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

After stimulation, cells were washed, transferred to serum-free DMEM medium and returned to the incubator for the indicated time period until preparation of cell extracts. Alternatively, after stimulation cells were immediately washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and placed on lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, 0.4% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride (PMSF) and 1 μg/ml of protease inhibitors (cocktail containing chymostatin, leupeptin, antipain and pepstatin). Cell extracts were then sonicated and centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000g, at 4 °C. Supernatants were recovered and the protein quantified by the BCA method. One mg of total cell extract protein was incubated overnight with 4 μg of primary antibody, under gentle shaking, at 4 °C. Protein A sepharose was then added to the immunoprecipitates and the mix was incubated for 2 h, after which beads were extensively washed with immunoprecipitation buffer (IPB, 10 mM Tris pH 7.0, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml of the protease inhibitors chymostatin, leupeptin, antipain and pepstatin). The final two of four washes were performed with IPB containing 300 mM NaCl. Beads were then diluted two times with sample buffer (0.25 M Tris pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 200 mM DTT, 20% glycerol), boiled for 5 min, and the proteins previously complexed with protein A sepharose beads collected into centrifugation filters and kept at −20 °C until analysis by Western blotting. Sixty μg of protein of the inputs (total cell extracts which were not incubated with antibody nor protein A sepharose) were also analysed in the immunoblot. As a control for non-specific binding, a co-immunoprecipitation assay was performed using normal IgGs from the host species of the primary antibody. For the analysis of phospho-GluA4 T855 levels, a similar immunoprecipitation protocol was used except that 200 μg of total cell extract protein were incubated with 3 μg of primary antibody.

Pull-down assays

After 24 h in vitro, HEK-GluA4 cells were transfected with GST-JIP-1 constructs encoding different domains of the scaffold protein, as previously described, and total cell extracts prepared at 36–40 h post-transfection. One mg of protein from each extract was incubated with PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1.5 h to diminish unspecific binding to GST, and then 50 μl of glutathione sepharose beads were added to the extracts. After 1 h of incubation at 4 °C, the beads were washed 6 times with PBS supplemented with 250 mM NaCl for the first 3 washes and with 300 mM of NaCl for the 3 final washes. Finally, the beads were diluted two times with sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and the proteins previously complexed with glutathione sepharose collected into centrifugation filters and kept at −20 °C until analysis by Western blotting. Sixty μg of protein of the inputs were also analysed in the immunoblot.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

Sixty μg of protein from total cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE, using polyacrylamide gels of 8–12.5%, and then transferred into a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were blocked with TBS-T (20 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.6, 0.1% Tween20) with 5% non-fat milk, for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with the primary antibody in TBS-T 0.5% milk, for 1 h at room temperature. Alternatively, the incubation with the primary antibody was performed overnight at 4 °C. After extensive washing, membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h at room temperature. After additional washes, the membranes were developed using the enhanced chemifluorescence (ECF) substrate, and scanned on the Storm 860 Gel and Blot Imaging System (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). The density of the bands was analysed with ImageQuant 5.0 software. For subsequent reprobing, the membranes were stripped of antibody with NaOH 0.2 M, blocked again and incubated with the appropriate antibodies.

Kainate injections and subcellular fractionation

In vivo studies were carried out using 6-week-old male Wistar rats (≈200 g) and the experiments were done in accordance with the European ethical guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (86/609/EEC). The animals were injected intraperitoneally with 10 mg/kg kainic acid (KA) or with sterile 0.9% NaCl (control rats). KA produces a characteristic seizure syndrome associated with pronounced hippocampal neurotoxicity (Silva et al., 2005). The animals that reliably presented seizures characterized by head movement, body tremor, and tonic–clonic convulsions, were sacrificed 2 h or 48 h after injection. Control animals were killed 48 h after injection. Brains were removed quickly and the hippocampi isolated and immersed in homogenizing buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (300 nM okadaic acid (OA) and 1 mM PMSF). Then, crude synaptosomal fractions (P2) were prepared using a previously described protocol (Carlin et al., 1980), with slight modifications. Briefly, tissue homogenization was performed using a potter to manually apply 10–15 strokes (1 ml/hippocampus). The homogenates were then centrifuged at 1000g for 10 min (Sorvall RT 6000D) and the supernatants (S1) transferred to fresh tubes and centrifuged at 10,000g for 15 min (Sorvall RC 5C Plus, SS-34 rotor). The supernatants were discarded and the pellets (P2) immersed in the homogenizing buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (300 nM OA, 1 mM PMSF and 1 μg/ml of chymostatin, leupeptin, antipain, and pepstatin), and homogenized with 5 manual strokes (250 μl/hippocampus). The homogenates were kept on ice for approximately 40 min to solubilize, and then stored at −80 °C until use. The entire process was carried out at 4 °C. One mg of total protein was used afterwards in co-immunoprecipitation assays.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means±S.E.M. of the indicated number of experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way variance analysis (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett’s test or the Bonferroni’s test. Alternatively, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney’s test was used, for all data involving n<5 without a normal distribution. These statistical analyses were performed using the software package GraphPad Prism 5.

Results

Overactivation of Ca-AMPARs induces JNK activation in a Ca2+-dependent and biphasic manner

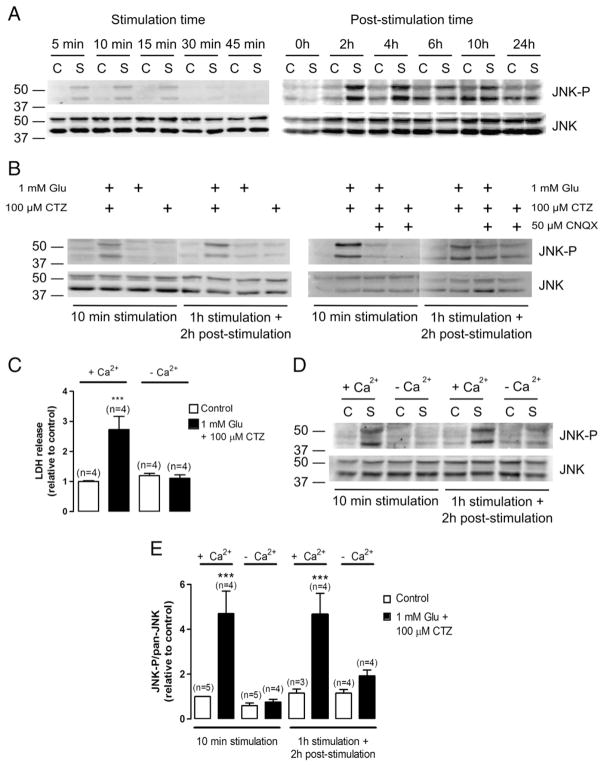

The involvement of the JNK signalling pathway on excitotoxic cell death mediated by Ca-AMPARs was addressed by stimulating HEK-GluA4 cells with 1 mM glutamate, in the presence of 100 μM CTZ. A time course of JNK activation, following Ca-AMPARs overstimulation, was examined within a range of stimulation periods from 5 min up to 1 h, and then within an array of post-stimulation periods after 1 h of stimulation. The total cell extracts used for Western blot analysis with an antibody against phospho-JNK (T183/Y185), which is considered the kinase active form, were prepared at the indicated time-points (Fig. 1A). The excitotoxic insult induced a biphasic activation of JNK, with a maximal phosphorylation within the first 15 min of stimulation and at 2 h–4 h post-stimulation (Fig. 1A, upper panels). Reprobing of the membranes with an antibody against total JNK showed that excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells did not alter total JNK protein levels (Fig. 1A, lower panels). Thus, our studies were further pursued at time points corresponding to the early (10 min) and late (2–4 h post-stimulation) phases of maximal JNK activation.

Fig. 1.

Excitotoxic stimulation of Ca-AMPARs with glutamate and CTZ induces biphasic, Ca2+-dependent JNK activation. Sixty μg of total protein were used for immunoblot analysis with an anti-phospho-JNK (T183/Y185) antibody. The membranes were reprobed with an anti-pan-JNK antibody. Each figure is representative of 3 assays performed with extracts of independent experiments (C– —control; S—stimulus). Control cells were incubated in sodium buffer with 2.5 mM Ca2+ in the absence of drugs. (A) Left panel: HEK-GluA4 cells were stimulated for the indicated time periods. Right panel: after 1 h of stimulation with glutamate plus CTZ, HEK-GluA4 cells were kept on serum-free culture medium for the indicated post-stimulation period. Stimulation periods of 10 min or 2 h of post-stimulation after 1 h of stimulation were chosen to pursue the experiments. (B) Left panel: HEK-GluA4 cells were exposed to glutamate, CTZ or both. Right panel: HEK-GluA4 cells were exposed to glutamate plus CTZ, in the presence or absence of CNQX, an antagonist of AMPARs. (C) HEK-GluA4 cells were submitted to excitotoxic stimulation for 1 h as previously described and after stimulation cells were returned to the incubator. LDH release to the extracellular medium was measured 24 h later. LDH leakage was significantly increased in cells submitted to excitotoxic stimulation in the presence of Ca2+, relatively to control. (LDH leakage Control=6.92%±5.83%). (D) HEK-GluA4 cells were stimulated with glutamate plus CTZ in the presence or absence of 2.5 mM Ca2+. Control cells were similarly incubated in sodium buffer with or without Ca2+ but in the absence of drugs. (E) Quantification of the ratio between the levels of phospho-JNK and total JNK. The results were normalized to the control corresponding to 10 min incubation in sodium buffer in the presence of Ca2+. Bars represent the mean±SEM of the indicated number of experiments. *** Significantly different from control (p<0.001, One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test).

In HEK-GluA4 cells, the stimulus with glutamate in the absence of CTZ is not toxic and does not increase the DNA-binding activity of AP-1 (Santos et al., 2006). Therefore, we investigated JNK phosphorylation under the same experimental conditions. An increase in the levels of phospho-JNK was only observed when HEK-GluA4 cells were subjected to an excitotoxic insult with glutamate in the presence of CTZ. In contrast, stimulation with glutamate or CTZ alone did not change the amount of phosphorylated JNK relative to control (Fig. 1B, left panel). Furthermore, CNQX, an antagonist of AMPARs, inhibited JNK activation induced by the excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells (Fig. 1B, right panel).

Interestingly, in HEK-GluA4 cells the excitotoxicity induced by overstimulation of Ca-AMPARs depends on the extracellular Ca2+ concentration (Santos et al., 2006). In support of previous observations, we show that excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells in a saline buffer with 2.5 mM Ca2+ induced a 3 fold increase in LDH release to the extracellular medium, while in the absence of Ca2+ the stimulus caused a release of LDH similar to the one observed in the control situation, thus indicating that the extracellular Ca2+ concentration was crucial to the death process (Fig. 1C). We then tested whether JNK activation was also influenced by Ca2+ influx. We showed that the increase in JNK activation, at an early and late time point, was observed only when stimulation was performed in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 1D). Indeed, when the saline buffer used in the excitotoxic stimulus included 2.5 mM Ca2+, JNK phosphorylation increased approximately 5 fold within 10 min of stimulation and at 2 h after stimulation, while in the absence of Ca2+ the changes in JNK phosphorylation were not significantly different from control (Fig. 1E).

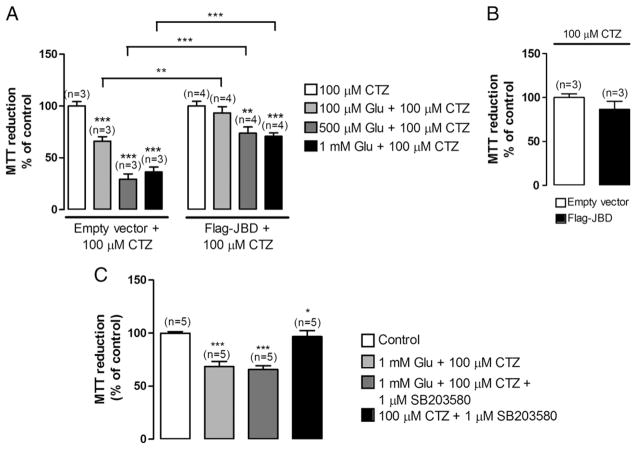

Overexpression of the JNK-binding domain (JBD) of JIP-1 protects HEK-GluA4 cells from excitotoxicity

To evaluate the contribution of the JNK signalling pathway to the excitotoxic response, HEK-GluA4 cells were transduced with the JNK binding domain of JIP-1 (JBD), which blocks the access of JNK to c-Jun and other substrates by a direct competitive mechanism (Bonny et al., 2001). For that purpose, HEK-GluA4 cells were either transfected with a plasmid encoding Flag-JBD or a control plasmid encoding the Flag epitope (empty vector). At 40 h post-transfection cells were exposed, during 1 h, to different concentrations of glutamate and 100 μM CTZ in saline buffer with 2.5 mM Ca2+ and cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay 24 h later. Cells transfected with Flag-JBD were less vulnerable to excitotoxic stimulation than cells transfected with the control plasmid since the effects of glutamate (100 μM–1 mM glutamate) stimulation on MTT reduction were less significant in cells expressing JBD. In fact, in these cells only high concentrations of glutamate (500 μM and 1 mM) decreased MTT reduction, by about 25% and 30% respectively. In cells expressing the empty vector, stimulation with 100 μM, 500 μM and 1 mM of glutamate decreased MTT reduction by about 35%, 70% and 65%, respectively (Fig. 2A). The viability of control cells was similar in cultures transfected with the empty vector or with the Flag-JBD form (Fig. 2B) which excludes a bias towards toxicity in non-stimulated transfected cells.

Fig. 2.

JNK inhibition protects HEK-GluA4 cells against excitotoxic cell damage, whereas p38 inhibition does not affect HEK-GluA4 viability. (A) HEK-GluA4 cultures were transfected with Flag-JBD, that includes the JNK binding domain of JIP-1, or with an empty vector using lipofectamine and exposed to glutamate and CTZ for 1 h, at 40 h post-transfection. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay 24 h after stimulation. Control cells were incubated in sodium buffer containing CTZ, and MTT reduction under these conditions considered as 100%. (B) MTT reduction of control cells. The MTT reduction in empty vector transfected cells was normalized to 100%. (C) HEK-GluA4 cells were stimulated, in the presence or absence of SB203580, for 1 h at 37 °C. When SB203580 was present, cells were pre-incubated with the drug for 1–2 h, at 37 °C. SB203580 was present during the post-stimulation period. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay 24 h after stimulation. Bars represent the mean±SEM of the indicated number of experiments. * Significantly different from control (*p<0.05; ***p<0.001; Mann–Whitney test).

Additionally, we analysed a possible contribution of the p38 MAPK to Ca-AMPAR-mediated cell death by performing the excitotoxic stimulation in the presence of 1 μM SB203580, a pharmacological inhibitor of the p38 signalling pathway (Lee et al., 1994). Cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay after a recovery period of 24 h. Excitotoxic stimulation in the presence of the p38 MAPK inhibitor did not afford protection to the cells, which showed a reduction of MTT of approximately 60% of the control, both in the presence or in the absence of the p38 MAPK inhibitor (Fig. 2C).

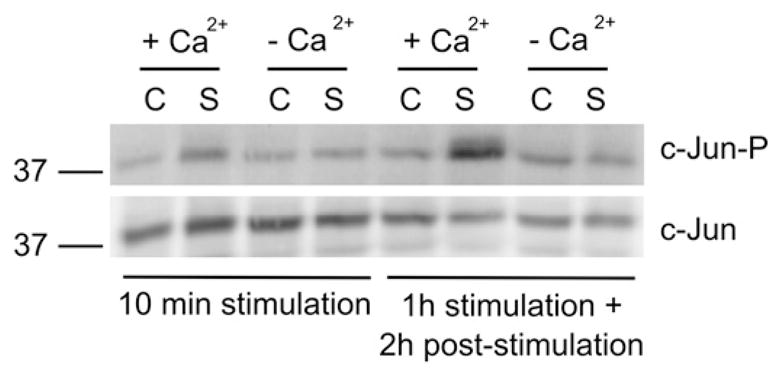

JNK substrate phosphorylation increases upon excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells

One of the best studied JNK substrates is the transcription factor c-Jun, which is phosphorylated by JNK on S63 and S73. To determine whether c-Jun phosphorylation increases after excitotoxic stimulation, we analysed the levels of phospho-c-Jun by Western blotting with an antibody selective for phosphorylation on S63. HEK-GluA4 cells were subjected to excitotoxic stimulation as previously described. Overactivation of Ca-AMPARs increased c-Jun phosphorylation, in a Ca2+-dependent manner, at an early and late time point, in accordance with the results regarding JNK activation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells increases the levels of phospho-c-Jun. HEK-GluA4 cells were stimulated as previously described. The effect of the extracellular Ca2+ concentration on c-Jun phosphorylation was tested by stimulating the cells in saline buffer in the presence or absence of 2.5 mM Ca2+. Sixty μg of total proteins were used for immunoblot analysis with an anti-phospho-c-Jun S63 antibody. The membranes were reprobed with an anti-c-Jun antibody. The figure is representative of 3 assays performed with extracts of independent experiments (C—control; S—stimulus).

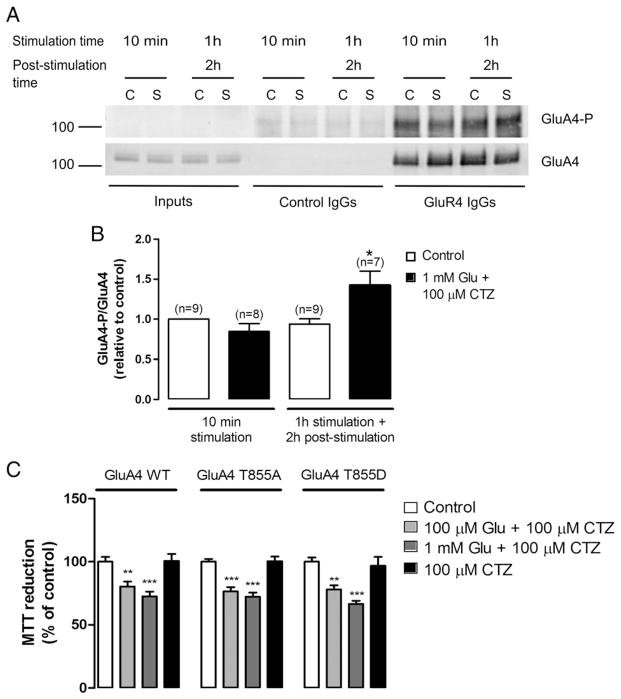

On the other hand, since the GluA4 subunit of AMPARs was recently described as a novel physiological JNK substrate in neurons and heterologous cells (Thomas et al., 2008), we investigated whether excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells could influence the levels of phospho-GluA4 at T855, the residue phosphorylated by JNK. At time points corresponding to maximal JNK activation, GluA4 subunits were immunoprecipitated from total cell extracts with an anti-GluA4 antibody and the immunocomplexes analysed by Western blot, with an anti-phospho-GluA4 (T855) antibody (Fig. 4). As a control for unspecific binding, total cell extracts were incubated with IgGs from normal rabbit serum. Although we observed GluA4 T855 phosphorylation in immunoprecipitates from control cells, there was a rise in GluA4 T855 phosphorylation 2 h after excitotoxic stimulation, a time point corresponding to the late phase of JNK activation. Membrane reprobing with an anti-GluA4 antibody indicated that the total levels of the GluA4 protein remained constant (Fig. 4A). Quantification of the immunoblots showed an increase in phospho-GluA4 T855 levels of about 1.35 fold relative to control (Fig. 4B). To clarify a possible role for the JNK-dependent phosphorylation of GluA4 T855 in the excitotoxic response we transfected HEK293A cells with a GluA4 wild type construct or with the mutant forms GluA4 T855A, a non-phosphorylatable mutant, and GluA4 T855D, a phosphomimetic mutant. Later, HEK293A cells were subjected to excitotoxic stimulation with glutamate plus CTZ, for 1 h at 37 °C and, after a recovery period of 24 h, cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay (Fig. 4C). The results showed no significant differences in the cell viability of cultures transfected with the distinct constructs.

Fig. 4.

Excitotoxic stimulation of HEK-GluA4 cells increases GluA4 phosphorylation at T855, a specific JNK phosphorylation site, but this phosphorylation does not influence HEK293A cell viability upon excitotoxic stimulation. (A) HEK-GluA4 cells were stimulated as previously described. Two hundred μg of protein were used for immunoprecipitation with an anti-GluA4 antibody or with control IgGs. The membranes were probed with an anti-phospho-GluA4 (T855) antibody (upper panel) and then reprobed with an anti-GluA4 antibody (lower panel). (B) The histogram represents the quantification of the immunoreactive bands. The ratio between phospho-GluA4 T855 and the total levels of GluA4 was normalized to the control (10 min). (C) HEK293A cells were transfected with GluA4 wild type (WT), GluA4 T855A, a non-phosphorylatable mutant, or GluA4 T855D, a phosphomimetic mutant. At 40 h post-transfection cells were stimulated as described. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay 24 h after stimulation (n=10). * Significantly different from control (**p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test).

The GluA4 subunit of AMPARs interacts with the JNK scaffold JIP-1

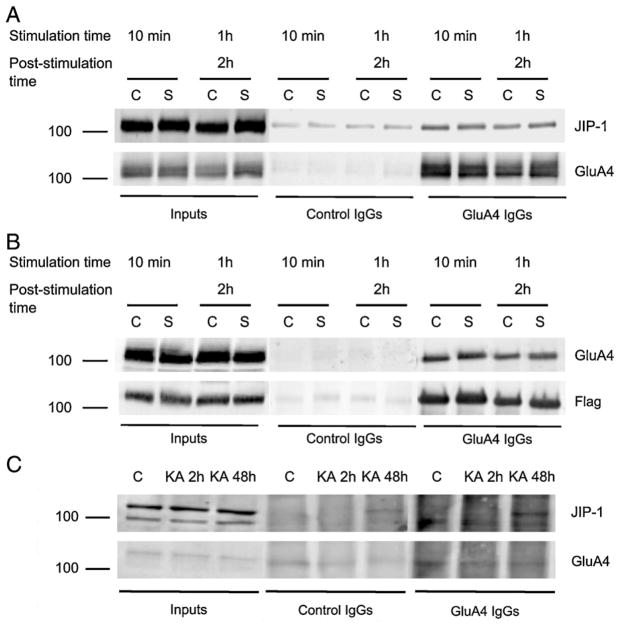

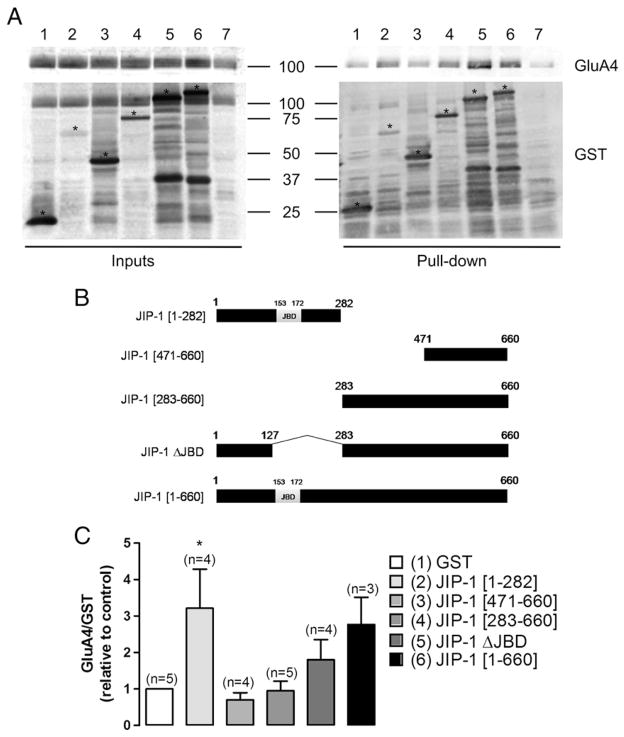

The components of the JNK pathway associate with several proteins, including scaffolds that can assemble the different members of the signalling complex and regulate their activity. Therefore, we looked into a possible interaction between the GluA4 subunit of AMPARs and the JIP-1 scaffold. We transiently expressed Flag-JIP-1 in HEK-GluA4 cells and these cultures were later used to evaluate the co-immunoprecipitation of GluA4 and JIP-1 under basal or excitotoxic stimulation. Cell extracts were prepared at time points corresponding to maximal JNK activation as indicated in Fig. 5. One mg of total protein was incubated either with anti-GluA4 IgGs or with normal rabbit IgGs as a control for unspecific binding. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated proteins was performed using an anti-JIP-1 antibody, and the membranes were then reprobed with an anti-GluA4 antibody. We observed that JIP-1 co-immunoprecipitated with GluA4. However, this interaction was not affected by the excitotoxic stimulation, at least for the time points analysed in the study (Fig. 5A). Likewise, using an anti-Flag antibody to immunoprecipitate cell extracts, we detected that GluA4 co-immunoprecipitated with Flag-JIP-1, thereby confirming the interaction between these two proteins (Fig. 5B). In additional studies we investigated whether an interaction between endogenous GluA4 and JIP-1 occurs in rat brain tissue and assessed whether this interaction is affected under excitotoxic conditions in vivo, in rats injected (i.p.) with KA. The co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed using solubilized hippocampal crude synaptosomal preparations (P2) in order to enrich the biological material both in the GluA4 subunit and in JIP-1, which accumulate at the synapse (Pellet et al., 2000; Whitmarsh et al., 2001; Esteban et al., 2003). One mg of protein from each preparation was incubated with either an anti-GluA4 antibody or normal rabbit serum IgGs as a control for unspecifc binding. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated proteins was performed using an anti-JIP-1 antibody. Each membrane was then reprobed with the anti-GluA4 antibody. Sixty μg of protein from hippocampal crude synaptosomal preparations (inputs) were also used for Western blotting. An interaction between endogenous GluA4 and JIP-1 was observed in the hippocampus, where a co-immunoprecipitation of JIP-1 with GluA4 was found exclusively in animals subjected to excitotoxic stimulation (Fig. 5C). Given these results, we investigated the region of JIP-1 involved in the interaction with the GluA4 subunit. HEK-GluA4 cells were transfected with distinct constructs, coding for different JIP-1 regions bound to GST: JIP-1 [1–282], JIP-1 [471–660], JIP-1 [283–660], JIP-1 [1–660] and JIP-1 ΔJBD, which has amino acid residues 127–282 deleted. GST pull-down assays were then performed with total extracts of cells expressing the different fusion proteins. Cells transfected with a construct containing GST alone were used as a control. The Western blot analysis was performed using an anti-GluA4 antibody and the membranes were reprobed with an anti-GST antibody. The results of the pull-down assays were qualitatively similar to those of the co-immunoprecipitation experiments, showing an interaction between the scaffold JIP-1 and GluA4 subunits of AMPARs (Fig. 6). This interaction occurs specifically through amino acid residues 1–282 of JIP-1, which were sufficient for maximal precipitation of GluA4 (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 5.

The JIP-1 scaffold protein interacts with the GluA4 subunit of AMPARs both in transfected HEK-GluA4 cells overexpressing Flag-JIP-1 and in hippocampal crude synaptosomal fractions. HEK-GluA4 cultures were transiently transfected with Flag-JIP-1 and, at 40 h post-transfection, cell extracts were prepared. One mg of total protein was immunoprecipitated with an anti-GluA4 antibody, or, alternatively, with an anti-Flag antibody. The membranes were probed with an anti-JIP-1 antibody (A) or an anti-GluA4 antibody (B), and then reprobed with the antibodies used to immunoprecipitate. The figure is representative of Western blot assays performed with extracts of four independent experiments. (C) Interaction between endogenous JIP-1 and GluA4 in rat brain tissue, following KA injection. One mg of total protein from hippocampal crude synaptosomal fractions (P2) was used in the immunoprecipitation assays with an anti-GluA4 antibody or with normal serum IgGs. The membranes were probed with an anti-JIP-1 antibody and then reprobed with an anti-GluA4 antibody. The figure is representative of three independent experiments. (C—control; S—stimulus; KA—kainate).

Fig. 6.

JIP-1 interacts with the GluA4 subunit through the N-terminal domain. (A) HEK-GluA4 cells were transfected with a series of GST-JIP-1 constructs and, at 40 h post-transfection, cell extracts were prepared. One mg of protein was used in each pull-down assay. Western blot analysis was performed using an anti-GluA4 (top) antibody, and membranes were then reprobed with an anti-GST antibody (bottom) (1—GST; 2—JIP-1 [1–282]; 3—JIP-1 [471–660]; 4—JIP-1 [283–660]; 5—JIP-1 ΔJBD; 6—JIP-1 [1–660]; 7—non-transfected HEK-GluA4). (B) Representation of the various GST-fusion proteins of JIP-1 used for pull-down in HEK-GluA4 cells. (C) Quantification of the ratio between the levels of GluA4 and GST, which was normalized to the control corresponding to GST-expressing cells. Bars represent the mean±SEM of the indicated number of experiments. *Significantly different from GST-expressing cells (p<0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test).

Discussion

Ca-AMPARs have been increasingly implicated in excitotoxic phenomena associated with transient global ischemia and other neurodegenerative disorders, such as sporadic ALS. Neurons expressing GluA4-containing AMPARs, such as spinal motor neurons (Vandenberghe et al., 2001) and those present in the reticular nucleus of the thalamus, are particularly vulnerable to AMPA-induced excitotoxicity (Weiss et al., 1994; Page and Everitt, 1995), pointing out that Ca-AMPARs containing the GluA4 subunit may play an important role in excitotoxic neuronal death. Thus, identifying excitotoxic signalling pathways mediated by these receptors will help unravelling their role in neurodegeneration. Using a heterologous system we showed that overactivation of GluA4-containing Ca-AMPARs induces JNK activation in a Ca2+-dependent manner and this pathway mediates, at least in part, HEK-GluA4 cell death. The expression of the JNK scaffold JIP-1 in HEK-GluA4 cells showed an interaction between this protein and the GluA4 subunit, and KA injection (i.p.) induced an interaction between endogenous JIP-1 and GluR4, in the rat hippocampus.

Excitotoxicity mediated by Ca-AMPARs involves a Ca2+-dependent JNK activation

The excessive stimulation of glutamate receptors causes neuronal death due to the [Ca2+]i overload. However, whether the increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration leads to cell death depends, among other factors, on the route of Ca2+ entry since it determines the intracellular signalling pathways activated afterwards (Franklin and Johnson, 1992; Sattler et al., 1998; Arundine and Tymianski, 2003; Friedman, 2006; Forder and Tymianski, 2009). In this work we used the HEK-GluA4 cells to investigate whether overactivation of Ca-AMPARs is coupled to JNK-mediated cell death. These cells do not express other glutamate receptors and therefore allow distinguishing the contribution of GluA4-containing Ca-AMPAR-mediated signalling pathways to cell death (Santos et al., 2006).

Our results showed that JNK is activated downstream of Ca-AMPARs, by a mechanism dependent on Ca2+ influx through these receptors, supporting a role for JNK in a Ca2+-dependent excitotoxic response. We observed an early phase of JNK activation within the first 15 min of stimulation and a later, more sustained phase, 2–4 h after the excitotoxic stimulation period. JNK activation was mediated by Ca-AMPARs, since it was inhibited by CNQX and, in both phases, it correlated with an increase in c-Jun phosphorylation. Noteworthy, JNK activation contributes to Ca-AMPAR-induced HEK-GluA4 cell death since overexpression of JBD afforded protection against excitotoxic stimulation. Accordingly, in numerous models of disease, the JNK pathway takes a prominent role in the death signalling mediated by transcription-dependent or independent events (Davis, 2000; Cui et al., 2007; Weston and Davis, 2007), including the neuronal death induced by excitotoxic and ischemic stimuli. JNK3, a neural-specific isoform, was shown to be involved in the neuronal death induced by KA injection (Yang et al., 1997) or ischemia–hypoxia insults (Kuan et al., 2003). Moreover, inhibition of JNK, both with the pharmacological compound SP600125 (Gao et al., 2005; Guan et al., 2005) or a JBD peptide (Borsello et al., 2003; Hirt et al., 2004; Guan et al., 2006; Esneault et al., 2008), conferred neuroprotection in focal and global ischemia models. Interestingly, previous studies indicate that in a JNK biphasic response, only the later and more sustained phase of JNK activation mediates death signalling (Hirt et al., 2004; Ventura et al., 2006). Thus, it is possible that the distinct phases of JNK activation we observed are associated with different functions of the kinase in the excitotoxic response. Although HEK-GluA4 cells were incubated at different time points with the JNK pathway inhibitors CEP11004 and SP600125, in a trial to discriminate between distinct roles of the two phases of JNK activation, the results were not conclusive due to the toxicity of these compounds in these cells (data not shown).

Using a cytotoxicity assay we showed that, in HEK-GluA4 cells, excitotoxicity induced by overstimulation of GluA4-containing Ca-AMPARs was dependent on the extracellular Ca2+ concentration. This is in agreement with our previous observations (Santos et al., 2006) and with the view that excessive Ca2+ influx plays a crucial role in neurodegeneration (Arundine and Tymianski, 2003; Forder and Tymianski, 2009). Furthermore, we observed that both phases of JNK activation and c-Jun phosphorylation on S63 following excitotoxic stimulation were prevented when Ca2+ was absent from the stimulation buffer, indicating that, in HEK-GluA4 cells, Ca-AMPAR-mediated JNK activation is a Ca2+-dependent event. This is in agreement with our previous findings showing the Ca2+-dependency of the AP-1 DNA-binding upon excitotoxic stimulation (Santos et al., 2006). Of note, Ca2+ entry into HEK-GluA4 cells is primarily due to influx through Ca-AMPAR channels (Utz and Verdoorn, 1997). There are several evidences that glutamatergic stimulation may activate MAPKs in a Ca2+-dependent manner. In particular, excitotoxic stimulation of primary neuronal cultures leads to the Ca2+-dependent activation of p38 MAPK (Kawasaki et al., 1997; Semenova et al., 2007; Soriano et al., 2008) and JNK (Ko et al., 1998). However, to our knowledge, this is the first report on the requirement of Ca2+ influx through Ca-AMPARs for JNK activation, which might be relevant when considering that the route of Ca2+ entry into the cell will determine the signalling pathways that are activated and, as a result, will settle Ca2+ toxicity (Sattler and Tymianski, 2000). Nevertheless, we cannot exclude that mechanisms affecting the cellular Na+ extrusion may contribute for HEK-GluA4 cell death. In fact, evidences suggest that the reversal of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) and its cleavage by calpains may contribute to enhance excitotoxic cell death (Bano et al., 2005; Araujo et al., 2007) and, in a heterologous system of HEK293 cells co-expressing both the GluA2 and GluA4 subunits, which oligomerize into heteromeric Ca2+-impermeable AMPARs, excitotoxicity was mediated by Na+ overload (Iizuka et al., 2000).

Recently, the AMPAR subunit GluA4 was described as a novel target of JNK (Thomas et al., 2008). It was shown that in cerebrocortical neurons, and in HEK293 cells, GluA4 is selectively phosphorylated by JNK on T855, but the role of this phosphorylation is not yet known. In our model, excitotoxic stimulation of Ca-AMPARs increased GluA4 T855 phosphorylation at a time point corresponding to the late phase of JNK activation. Upon overstimulation with glutamate and CTZ, the viability of HEK293A cells transfected with GluA4 T855 mutants was not different from HEK293A cells expressing wild type GluA4, suggesting that phosphorylation of GluA4 T855 does not contribute to excitotoxicity. However, we cannot exclude that, in neurons, the phosphorylation of GluA4 T855 might have a role in the excitotoxic response, since GluA4 phosphorylation might regulate the interaction with neuronal-specific partners.

The JNK scaffold JIP-1 interacts with GluA4-containing Ca-AMPARs

An important issue regarding excitotoxicity-induced JNK activation concerns the organization of the signalling complexes and how they are brought into the vicinity of glutamate receptors. It is generally accepted that scaffold proteins, which assemble the components of a pathway, regulate the activation of signalling cascades and confer specificity to the activated pathways (Davis, 2000; Whitmarsh, 2006). We detected an interaction between JIP-1 and the GluA4 subunit in HEK-GluA4 cells transduced with Flag-JIP-1, supporting the previous observation that both JNK and JIP-1 may be present in immunocomplexes with the GluA2L and GluA4 subunits of AMPARs (Thomas et al., 2008). Using a series of GST-JIP-1 deletion constructs we identified the N-terminal domain of JIP-1 within amino acids 1–282 as the region responsible for the interaction with GluA4. Interestingly, most interactions described for JIP-1, however, occur through its C-terminal (after amino acid 282), except for Notch-1 and JNK that bind both to the JBD located in the N-terminal. Using an in vivo model of excitotoxicity, the KA i.p. injection in adult rats, that induces hippocampal neuronal death primarily through the activation of AMPARs (Tomita et al., 2007), and leads to the activation of a cytotoxic JNK pathway (Yang et al., 1997; Whitmarsh et al., 2001), we showed an interaction between JIP-1 and GluA4 48 h after KA injection, a time point that usually matches with neuronal death (Kasof et al., 1995; Tokuhara et al., 2007). Possibly, post-translational modifications of these proteins are needed in order for them to interact in the hippocampus of adult rats upon an excitotoxic insult. Therefore, our results suggest that JIP-1 may have a role in the propagation of the excitotoxic signals evoked by AMPARs. In agreement with this, deletion of the Jip-1 gene confers protection against KA-induced excitotoxicity in hippocampal neurons (Whitmarsh et al., 2001). The JIP-1 scaffold was also shown to be crucial for ischemia-induced sustained JNK phosphorylation and subsequent neuronal death (Im et al., 2003). Moreover, JIP-1 was also implicated in the regulation of the signalling mediated by KA receptors (Zhang et al., 2007) and by NMDA receptors (Kennedy et al., 2007). However, in these studies, an interaction between JIP-1 and the glutamate receptor subunits was not shown.

Taken together, our results show that overstimulation of Ca-AMPARs induces a death pathway mediated by JNK, which requires Ca2+ influx. The JNK scaffold JIP-1 may interact with the GluA4 subunit of AMPARs through its N-terminal domain, suggesting that in vivo JIP-1 might be a molecular link between GluA4-containing Ca-AMPARs and the JNK pathway, contributing to the propagation of the excitotoxic signal.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Doctor RJ Davis, Doctor J Ham and Doctor K Keinänen for the plasmid constructs provided that allowed us to perform this work, Doctor M Iizuka and EL Barsoumian for the HEK-GluA4 cell line used as a model, and Doctor AP Silva for the assistance in the KA injections. This work was supported by Biogen Idec Portugal and Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), grant number PTDC/BIA-BCM/71789/2006. M. V. received a grant from Biogen Idec Portugal.

References

- Araujo IM, Carreira BP, Pereira T, Santos PF, Soulet D, Inacio A, Bahr BA, Carvalho AP, Ambrosio AF, Carvalho CM. Changes in calcium dynamics following the reversal of the sodium–calcium exchanger have a key role in AMPA receptor-mediated neurodegeneration via calpain activation in hippocampal neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14 (9):1635–1646. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arundine M, Tymianski M. Molecular mechanisms of calcium-dependent neurodegeneration in excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2003;34 (4–5):325–337. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bano D, Young KW, Guerin CJ, Lefeuvre R, Rothwell NJ, Naldini L, Rizzuto R, Carafoli E, Nicotera P. Cleavage of the plasma membrane Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in excitotoxicity. Cell. 2005;120 (2):275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A, Sibilia M, Wagner EF. Aminoterminal phosphorylation of c-Jun regulates stress-induced apoptosis and cellular proliferation. Nat Genet. 1999;21 (3):326–329. doi: 10.1038/6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonny C, Oberson A, Negri S, Sauser C, Schorderet DF. Cell-permeable peptide inhibitors of JNK: novel blockers of beta-cell death. Diabetes. 2001;50 (1):77–82. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsello T, Clarke PG, Hirt L, Vercelli A, Repici M, Schorderet DF, Bogousslavsky J, Bonny C. A peptide inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase protects against excitotoxicity and cerebral ischemia. Nat Med. 2003;9 (9):1180–1186. doi: 10.1038/nm911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht S, Kirchhof R, Chromik A, Willesen M, Nicolaus T, Raivich G, Wessig J, Waetzig V, Goetz M, Claussen M, Pearse D, Kuan CY, Vaudano E, Behrens A, Wagner E, Flavell RA, Davis RJ, Herdegen T. Specific pathophysiological functions of JNK isoforms in the brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21 (2):363–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham SD, Kwak S, Jones AK, Blackshaw SE, Sattelle DB. Edited GluR2, a gatekeeper for motor neurone survival? Bioessays. 2008;30 (11–12):1185–1192. doi: 10.1002/bies.20836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderone A, Jover T, Noh KM, Tanaka H, Yokota H, Lin Y, Grooms SY, Regis R, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Ischemic insults derepress the gene silencer REST in neurons destined to die. J Neurosci. 2003;23 (6):2112–2121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02112.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin RK, Grab DJ, Cohen RS, Siekevitz P. Isolation and characterization of postsynaptic densities from various brain regions: enrichment of different types of postsynaptic densities. J Cell Biol. 1980;86 (3):831–845. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Zhang M, Zhang YQ, Xu ZH. JNK pathway: diseases and therapeutic potential. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28 (5):601–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy S, Kelly L, Farrant M. Regulation of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors: synaptic plasticity and beyond. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16 (3):288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 2000;103 (2):239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens M, Rogers JS, Cavanagh J, Raitano A, Xia Z, Halpern JR, Greenberg ME, Sawyers CL, Davis RJ. A cytoplasmic inhibitor of the JNK signal transduction pathway. Science. 1997;277 (5326):693–696. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esneault E, Castagne V, Moser P, Bonny C, Bernaudin M. D-JNKi, a peptide inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase, promotes functional recovery after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;152 (2):308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban JA, Shi SH, Wilson C, Nuriya M, Huganir RL, Malinow R. PKA phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits controls synaptic trafficking underlying plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6 (2):136–143. doi: 10.1038/nn997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer D, Kask K, Brusa R, Kornau HC, Kolhekar R, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Jensen V, Hvalby O, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH. Neurological dysfunctions in mice expressing different levels of the Q/R site-unedited AMPAR subunit GluR-B. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2 (1):57–64. doi: 10.1038/4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forder JP, Tymianski M. Postsynaptic mechanisms of excitotoxicity: involvement of postsynaptic density proteins, radicals, and oxidant molecules. Neuroscience. 2009;158 (1):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JL, Johnson EM., Jr Suppression of programmed neuronal death by sustained elevation of cytoplasmic calcium. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15 (12):501–508. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90103-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK. Calcium: a role for neuroprotection and sustained adaptation. Mol Interv. 2006;6 (6):315–329. doi: 10.1124/mi.6.6.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Signore AP, Yin W, Cao G, Yin XM, Sun F, Luo Y, Graham SH, Chen J. Neuroprotection against focal ischemic brain injury by inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and attenuation of the mitochondrial apoptosis-signaling pathway. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25 (6):694–712. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter JA, Petrozzino JJ, Aronica EM, Rosenbaum DM, Opitz T, Bennett MV, Connor JA, Zukin RS. Global ischemia induces downregulation of Glur2 mRNA and increases AMPA receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx in hippocampal CA1 neurons of gerbil. J Neurosci. 1997;17 (16):6179–6188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06179.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan QH, Pei DS, Zhang QG, Hao ZB, Xu TL, Zhang GY. The neuroprotective action of SP600125, a new inhibitor of JNK, on transient brain ischemia/reperfusion-induced neuronal death in rat hippocampal CA1 via nuclear and non-nuclear pathways. Brain Res. 2005;1035 (1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan QH, Pei DS, Zong YY, Xu TL, Zhang GY. Neuroprotection against ischemic brain injury by a small peptide inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) via nuclear and non-nuclear pathways. Neuroscience. 2006;139 (2):609–627. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt L, Badaut J, Thevenet J, Granziera C, Regli L, Maurer F, Bonny C, Bogousslavsky J. D-JNKI1, a cell-penetrating c-Jun-N-terminal kinase inhibitor, protects against cell death in severe cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2004;35 (7):1738–1743. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131480.03994.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof PR, Lee PY, Yeung G, Wang RF, Podos SM, Morrison JH. Glutamate receptor subunit GluR2 and NMDAR1 immunoreactivity in the retina of macaque monkeys with experimental glaucoma does not identify vulnerable neurons. Exp Neurol. 1998;153 (2):234–241. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka M, Nishimura S, Wakamori M, Akiba I, Imoto K, Barsoumian EL. The lethal expression of the GluR2flip/GluR4flip AMPA receptor in HEK293 cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12 (11):3900–3908. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im JY, Lee KW, Kim MH, Lee SH, Ha HY, Cho IH, Kim D, Yu MS, Kim JB, Lee JK, Kim YJ, Youn BW, Yang SD, Shin HS, Han PL. Repression of phospho-JNK and infarct volume in ischemic brain of JIP1-deficient mice. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74 (2):326–332. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasof GM, Mandelzys A, Maika SD, Hammer RE, Curran T, Morgan JI. Kainic acid-induced neuronal death is associated with DNA damage and a unique immediate-early gene response in c-fos-lacZ transgenic rats. J Neurosci. 1995;15 (6):4238–4249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04238.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y, Ito K, Sun H, Aizawa H, Kanazawa I, Kwak S. Glutamate receptors: RNA editing and death of motor neurons. Nature. 2004;427 (6977):801. doi: 10.1038/427801a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Morooka T, Shimohama S, Kimura J, Hirano T, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Activation and involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in glutamate-induced apoptosis in rat cerebellar granule cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272 (30):18518–18521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy NJ, Martin G, Ehrhardt AG, Cavanagh-Kyros J, Kuan CY, Rakic P, Flavell RA, Treistman SN, Davis RJ. Requirement of JIP scaffold proteins for NMDA-mediated signal transduction. Genes Dev. 2007;21 (18):2336–2346. doi: 10.1101/gad.1563107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjoller C, Diemer NH. GluR2 protein synthesis and metabolism in rat hippocampus following transient ischemia and ischemic tolerance induction. Neurochem Int. 2000;37 (1):7–15. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(00)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HW, Park KY, Kim H, Han PL, Kim YU, Gwag BJ, Choi EJ. Ca2+-mediated activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and nuclear factor kappa B by NMDA in cortical cell cultures. J Neurochem. 1998;71 (4):1390–1395. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan CY, Whitmarsh AJ, Yang DD, Liao G, Schloemer AJ, Dong C, Bao J, Banasiak KJ, Haddad GG, Flavell RA, Davis RJ, Rakic P. A critical role of neural-specific JNK3 for ischemic apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100 (25):15184–15189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336254100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukekov NV, Xu Z, Greene LA. Direct interaction of the molecular scaffolds POSH and JIP is required for apoptotic activation of JNKs. J Biol Chem. 2006;281 (22):15517–15524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak S, Weiss JH. Calcium-permeable AMPA channels in neurodegenerative disease and ischemia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16 (3):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, Gallagher TF, Kumar S, Green D, McNulty D, Blumenthal MJ, Heys JR, Landvatter SW, et al. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372 (6508):739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SJ, Zukin RS. Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity and neuronal death. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30 (3):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Lau L, Wei J, Zhu D, Zou S, Sun HS, Fu Y, Liu F, Lu Y. Expression of Ca (2+)-permeable AMPA receptor channels primes cell death in transient forebrain ischemia. Neuron. 2004;43 (1):43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML. Glutamate receptors at atomic resolution. Nature. 2006;440 (7083):456–462. doi: 10.1038/nature04709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh KM, Yokota H, Mashiko T, Castillo PE, Zukin RS, Bennett MV. Blockade of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors protects hippocampal neurons against global ischemia-induced death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102 (34):12230–12235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505408102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page KJ, Everitt BJ. The distribution of neurons coexpressing immunoreactivity to AMPA-sensitive glutamate receptor subtypes (GluR1-4) and nerve growth factor receptor in the rat basal forebrain. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7 (5):1022–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini-Giampietro DE, Gorter JA, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. The GluR2 (GluR-B) hypothesis: Ca(2+)-permeable AMPA receptors in neurological disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20 (10):464–470. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellet JB, Haefliger JA, Staple JK, Widmann C, Welker E, Hirling H, Bonny C, Nicod P, Catsicas S, Waeber G, Riederer BM. Spatial, temporal and subcellular localization of islet-brain 1 (IB1), a homologue of JIP-1, in mouse brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12 (2):621–632. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng PL, Zhong X, Tu W, Soundarapandian MM, Molner P, Zhu D, Lau L, Liu S, Liu F, Lu Y. ADAR2-dependent RNA editing of AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 determines vulnerability of neurons in forebrain ischemia. Neuron. 2006;49 (5):719–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Behrens A. Role of the AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun in developing, adult and injured brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;78 (6):347–363. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos AE, Duarte CB, Iizuka M, Barsoumian EL, Ham J, Lopes MC, Carvalho AP, Carvalho AL. Excitotoxicity mediated by Ca2+-permeable GluR4-containing AMPA receptors involves the AP-1 transcription factor. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13 (4):652–660. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Tymianski M. Molecular mechanisms of calcium-dependent excitotoxicity. J Mol Med. 2000;78 (1):3–13. doi: 10.1007/s001090000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Charlton MP, Hafner M, Tymianski M. Distinct influx pathways, not calcium load, determine neuronal vulnerability to calcium neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 1998;71 (6):2349–2364. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71062349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeburg PH, Hartner J. Regulation of ion channel/neurotransmitter receptor function by RNA editing. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13 (3):279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova MM, Maki-Hokkonen AM, Cao J, Komarovski V, Forsberg KM, Koistinaho M, Coffey ET, Courtney MJ. Rho mediates calcium-dependent activation of p38alpha and subsequent excitotoxic cell death. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10 (4):436–443. doi: 10.1038/nn1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AP, Xapelli S, Pinheiro PS, Ferreira R, Lourenco J, Cristovao A, Grouzmann E, Cavadas C, Oliveira CR, Malva JO. Up-regulation of neuropeptide Y levels and modulation of glutamate release through neuropeptide Y receptors in the hippocampus of kainate-induced epileptic rats. J Neurochem. 2005;93 (1):163–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano FX, Martel MA, Papadia S, Vaslin A, Baxter P, Rickman C, Forder J, Tymianski M, Duncan R, Aarts M, Clarke P, Wyllie DJ, Hardingham GE. Specific targeting of pro-death NMDA receptor signals with differing reliance on the NR2B PDZ ligand. J Neurosci. 2008;28 (42):10696–10710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1207-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GM, Lin DT, Nuriya M, Huganir RL. Rapid and bi-directional regulation of AMPA receptor phosphorylation and trafficking by JNK. EMBO J. 2008;27 (2):361–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuhara D, Sakuma S, Hattori H, Matsuoka O, Yamano T. Kainic acid dose affects delayed cell death mechanism after status epilepticus. Brain Dev. 2007;29 (1):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita S, Byrd RK, Rouach N, Bellone C, Venegas A, O’Brien JL, Kim KS, Olsen O, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. AMPA receptors and stargazin-like transmembrane AMPA receptor-regulatory proteins mediate hippocampal kainate neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104 (47):18784–18788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708970104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama M, Rodriguez-Puertas R, Cortes R, Pazos A, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Flip and flop splice variants of AMPA receptor subunits in the spinal cord of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Synapse. 2002;45 (4):245–249. doi: 10.1002/syn.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz AL, Verdoorn TA. Recombinant AMPA receptors with low Ca2+ permeability increase intracellular Ca2+ in HEK 293 cells. NeuroReport. 1997;8 (8):1975–1980. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199705260-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe W, Bindokas VP, Miller RJ, Robberecht W, Brorson JR. Subcellular localization of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors in spinal motoneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14 (2):305–314. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura JJ, Hubner A, Zhang C, Flavell RA, Shokat KM, Davis RJ. Chemical genetic analysis of the time course of signal transduction by JNK. Mol Cell. 2006;21 (5):701–710. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JH, Sensi SL. Ca2+-Zn2+ permeable AMPA or kainate receptors: possible key factors in selective neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23 (8):365–371. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JH, Yin HZ, Choi DW. Basal forebrain cholinergic neurons are selectively vulnerable to AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated neurotoxicity. Neuroscience. 1994;60 (3):659–664. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JH, Sensi SL, Koh JY. Zn(2+): a novel ionic mediator of neural injury in brain disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21 (10):395–401. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston CR, Davis RJ. The JNK signal transduction pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19 (2):142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh AJ. The JIP family of MAPK scaffold proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34 (Pt 5):828–832. doi: 10.1042/BST0340828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh AJ, Kuan CY, Kennedy NJ, Kelkar N, Haydar TF, Mordes JP, Appel M, Rossini AA, Jones SN, Flavell RA, Rakic P, Davis RJ. Requirement of the JIP1 scaffold protein for stress-induced JNK activation. Genes Dev. 2001;15 (18):2421–2432. doi: 10.1101/gad.922801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang DD, Kuan CY, Whitmarsh AJ, Rincon M, Zheng TS, Davis RJ, Rakic P, Flavell RA. Absence of excitotoxicity-induced apoptosis in the hippocampus of mice lacking the Jnk3 gene. Nature. 1997;389 (6653):865–870. doi: 10.1038/39899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QX, Pei DS, Guan QH, Sun YF, Liu XM, Zhang GY. Crosstalk between PSD-95 and JIP1-mediated signaling modules: the mechanism of MLK3 activation in cerebral ischemia. Biochemistry. 2007;46 (13):4006–4016. doi: 10.1021/bi0615386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]