Abstract

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are hormone-sensing transcription factors that translate dietary or endocrine signals into changes in gene expression. Therefore, the adoption of orphan NRs through the identification of their endogenous ligands is a key element for our understanding of their biology. In this minireview, we give an update on recent progress in regard to endogenous ligands for a cluster of NRs with high sequence homology, namely peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and γ, Rev-erbα, and related receptors. This knowledge about the nature and physiology of these ligands may create new opportunities for therapeutic drug development.

Keywords: Gene Expression, Ligand-binding Protein, Metabolic Regulation, Nuclear Receptors, Receptors

General Considerations of Endogenous Ligands for Nuclear Receptors

The superfamily of nuclear receptors (NRs)3 controls processes as diverse as development, inflammation, toxicology, reproduction, and metabolism (1). There are 48 members encoded in the human genome (49 in mouse) (1). The term endogenous ligand in regard to NRs describes a naturally occurring small molecule that elicits a conformational change in the NR upon binding (2). This conformational change alters the cellular location of the NRs and/or their interaction with cofactors, which ultimately translates into changes in gene expression and explains why these transcription factors are referred to as “ligand-activated” (3). Until the identification of such endogenous ligands, the receptor is called an orphan NR (1).

The known endogenous ligands for NRs consist of a wide range of chemical structures, such as bile acids, phospholipids, steroid hormones, thyroid hormone, retinoids, and vitamin D (4–10). Thus, although many of these are derived from cholesterol, a definition of the term endogenous ligand based on chemical structure is impossible. Some endogenous ligands, such as estrogens, were used as radiolabeled reagents to find their corresponding NR by identifying their binding partners (1). Other ligands were found integrated in the NR ligand-binding domains (LBDs) by solving their crystal structure (11–13) or by immunoprecipitating the NR (14).

Because there are NRs that have been described to bind a variety of different physiological ligands, which is especially the case for NRs with a spacious LBD (15), it can be hard to determine which one is the “real” endogenous ligand (14, 16, 17). Future studies may present evidence beyond the proof of in vitro binding to consolidate these ongoing debates. As an example, the cellular levels of a previously identified ligand (18) were shown to be far lower than required to induce NR activation (19). Therefore, the required features for such ligands usually comprise nuclear availability, high binding potency (in the nanomolar range), ability to induce a conformational change in the protein structure, and a NR-related physiological function as a hormone (1).

Considering the abundant expression of several NRs, it has also been suggested that one and the same NR may have distinct endogenous ligands in distinct tissues or cell types (20). This is of specific interest because a therapeutic intervention could selectively target the availability of one ligand without interfering with the desired effects of another. These interventions could range from controlling the biosynthesis of endogenous ligands to the modulation of processes involved in their inactivation. Therefore, detailed knowledge will be required to design therapeutics that specifically modify the availability of endogenous ligands. In this minireview, we focus on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α (PPARα; NR1C1) and γ (PPARγ; NR1C3), Rev-erbα (NR1D1), and retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor α (RORα; NR1F1), a cluster of NRs with high sequence homology for which much has recently been learned about endogenous ligands.

PPARα

PPARα is highly expressed in liver and controls the expression of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, ketogenesis, lipid transport, gluconeogenesis, glycogen metabolism, and inflammation (21, 22). Mice with a disruption of the PPARα gene develop hepatic steatosis due to impaired fatty acid oxidation and fasting hypoglycemia (22). PPARα is therefore considered the key player in the hepatic fasting response. Activation of PPARα by therapeutically used fibrates leads to a decrease in serum triglycerides and an increase in HDL cholesterol (23).

PPARα and PPAR subtypes β and γ bind to DNA as heterodimers with retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) (24). The binding motifs for all PPARs consist of a direct repeat of the core consensus half-site ATTGCA spaced by one nucleotide. These motifs, located in the promoter and enhancer regions of target genes, are referred to as PPAR-response elements (25–27).

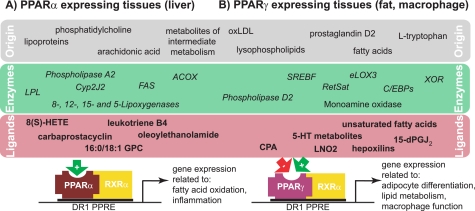

Soon after its discovery, several studies described the activation of PPARα by enzymatically derived derivatives of arachidonic acid, such as the eicosanoids leukotriene B4 and (8S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids, carbaprostacyclin, and unsaturated fatty acids (20, 28–32). Most of these ligands were identified using in vitro approaches. Because the actual source of these lipids is mainly dietary uptake, the concept of PPARα as a physiological lipid sensor developed soon after (28, 29).

In addition, oxidized phospholipids, which are components of oxidized LDLs, were identified to activate PPARα in endothelial cells (5). This activation was dependent on the activity of phospholipase A2, which suggests that these phospholipids may be precursors for endogenously generated activators (5). Similarly, the enzyme that locally hydrolyzes triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and releases fatty acids, lipoprotein lipase, was shown to generate PPARα-activating species in these cells (33). Addition of albumin abrogated the PPARα activation, which implicates protein binding of the lipoprotein lipase-generated fatty acids as an important factor (34). Another phospholipid-related species, oleoylethanolamide (OEA), was shown to regulate feeding and body weight through PPARα activation. OEA can bind and induce PPARα in the nanomolar range (EC50 = 120 nm), increases lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation, and is found at PPARα-activating concentrations in the small intestine (35). Interestingly, also adipose tissue has been shown to generate OEA (36). Thus, OEA could link fasting-induced lipolysis to hepatic PPARα activation. Further studies are required to fully understand OEA in the context of the hepatic fasting response.

Other approaches focused on the involvement of lipid-metabolizing enzymes in the generation of PPARα-activating ligands. ACOX1 (acyl-CoA oxidase 1) and several dehydrogenases have been implicated in the inactivation of putative PPARα ligands, whereas fatty acid synthase (FAS), 8-, 12-, 15-, and 5-lipoxygenases, and the P450 cytochrome Cyp2J2 have been associated with their synthesis (37–40).

In an elegant recent study, Chakravarthy et al. (14) re-expressed FLAG-tagged PPARα in the livers of PPARα−/− mice in the presence or absence of hepatic FAS and gently affinity-captured the NR without disrupting the binding of potential endogenous ligands. Tandem mass spectrometry identified 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoly-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (16:0/18:1 GPC) as the only PPARα-bound lipid that was dependent on the presence of FAS, one of the putative ligand-synthesizing enzymes (37). 16:0/18:1 GPC was competitively displaced by synthetic PPARα ligands, induced hepatic gene expression similar to synthetic ligands, and enhanced the interaction of the NR with cofactor peptides (14), thus fulfilling most of the criteria for a specific ligand. These findings were corroborated by studies showing that an application of 16:0/18:1 GPC to the portal vein system alleviated hepatic steatosis. Interestingly, the authors found that peripheral lipids, entering the liver via the liver artery, were unable to activate hepatic PPARα, suggesting that the origin of 16:0/18:1 GPC may be important (14). More studies are necessary to fully understand which role 16:0/18:1 GPC plays in the activation of hepatic PPARα during fasting. Part of this is the determination of the mechanism that allows this hydrophilic/charged ligand to access the nucleus for binding PPARα. These findings may allow us to evaluate whether the endogenous synthesis/metabolism of 16:0/18:1 GPC could present a potential drug target for lipid disorders. Potential components of ligand formation for PPARα are summarized in Fig. 1A.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of metabolic precursors and biosynthetic enzymes of putative ligands for PPARα and PPARγ. Both receptors bind DNA as heterodimers with RXRα to specific PPAR-response elements (PPREs) in target genes, although the binding is cell type-specific. oxLDL, oxidized LDL; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; 8(S)-HETE, (8S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; LNO2, nitrolinoleic acid; 15-dPGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2.

PPARγ

PPARγ is highly expressed in adipose tissue and is the master regulator of adipocyte differentiation (41). Lower expression of PPARγ can be found in other cell types, such as macrophages, where it regulates inflammation and glucose and lipid metabolism (42, 43) through cell type-specific DNA binding (44). Thiazolidinediones (TZDs), which are used clinically as insulin-sensitizing drugs, are potent synthetic PPARγ activators that induce adipogenesis (45). Thus, knowledge about the bona fide endogenous PPARγ ligand could create new opportunities in the treatment of insulin resistance and obesity.

As for PPARα, oxidized LDL has been identified early on to contain putative PPARγ ligands. Examples are the dehydration product of prostaglandin D2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2, and derivatives of certain mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids (18, 31, 46–48). Most of these ligands bind PPARγ with low affinity and may not be present at cellular concentrations necessary to activate this NR (19). By contrast, nitroalkene derivatives of linoleic acid, such as nitrolinoleic acid, were shown to bind PPARγ as potently as TZDs and were found at activating concentrations in human red cells and plasma (49, 50). Although the chemistry of nitrolinoleic acid has been largely understood (51), the physiological context of these nitro derivatives in regard to PPARγ signaling is still unclear.

Early studies proposed the SREBF (sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor) to link PPARγ ligand production to fatty acid synthesis (52). Although the SREBF-dependent synthesized compound was secreted into cell culture media (52), its identity has not been determined. Other approaches investigated the stage of adipocyte differentiation, during which the production of an endogenous ligand is most likely. Using a reporter cell system, Tzameli et al. (53) demonstrated that a PPARγ LBD-activating species was produced downstream of C/EBPβ (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β), concomitant with the induction of PPARγ expression in 3T3-L1 cells. Follow-up studies implicated the enzyme xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) in this transitional rise in PPARγ activity, and mice deficient in XOR were found to have less adipose tissue (54). However, the enzymatic product of XOR driving adipogenesis is still unknown. Depletion of the enzyme retinol saturase (RetSat), a direct transcriptional target of PPARγ and induced early during differentiation, inhibited adipocyte conversion (55). Providing the putative product 13,14-dihydroretinol did not rescue adipocyte differentiation, which suggests that this enzyme may have an additional role than the sole generation of 13,14-dihydroretinol (55). RetSat overexpression enhanced adipocyte conversion and PPARγ activity; thus, RetSat enzymatic activity may be required for the production of an endogenous ligand. Mice with a RetSat deletion exhibited a surprising increase in adiposity and PPARγ target gene expression (56). This shows the complexity of RetSat function in vivo, which needs further investigation.

eLOX3 (epidermis-type lipoxygenase 3) has been described to play a role in early adipocyte differentiation by the generation of the arachidonic acid derivatives hepoxilins (16). Interestingly, Hallenborg et al. (16) could show that eLOX3 cooperates with XOR in the activation of a Gal DNA-binding domain/PPARγ LBD reporter, which suggests that both enzymes converge in the same pathway. This pathway could work via reactive oxygen species (ROS) as intermediates, which are generated by XOR and further metabolized by eLOX3 (16, 54). Indeed, neutralizing ROS by the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine inhibits adipocyte differentiation (16). Moreover, an RNAi-based genetic screen for oxidative stress resistance discovered that silencing RetSat increased the survival of oxidant-exposed fibroblasts (57). This could implicate RetSat in ROS metabolism. However, the resulting hypothesis, that the synthesis of an endogenous PPARγ ligand involves radical lipid modifications, needs further investigation.

By using a reverse strategy, searching for natural metabolites that contain the indole acetate structure of the synthetic PPARγ ligand indomethacin, a recent study identified cellular 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT; serotonin) metabolites as PPARγ ligands (58). Waku et al. (58) showed that 5-methoxyindole acetate and 5-hydroxyindole acetate were able to activate PPARγ in adipocytes and macrophages. Indeed, 5-HT receptor-independent effects of 5-HT on glucose and lipid metabolism had been reported previously (59). 5-Methoxyindole acetate and 5-hydroxyindole acetate bound the PPARγ LBD in a distinct way because the PPARγ antagonist T0070907, which blocks binding of synthetic TZD drugs, had little effect on the activation of PPARγ by these 5-HT metabolites. Supplementing THP-1 macrophages with 5-HT induced PPARγ target gene expression, and the pharmacologic inhibition of 5-HT-metabolizing enzymes, such as the monoamine oxidase, prevented this induction. Because the highest peripheral levels of 5-HT are reached in the gastrointestinal tract, the authors argued that these metabolites interconnect the previously shown positive effects of PPARγ activation on experimental colitis (60) and that macrophages transport these compounds to PPARγ-expressing target tissues (58). Additional studies will reveal more PPARγ-dependent physiology of the 5-HT metabolites and how they relate to other endogenous ligands.

Tsukahara et al. (61) identified the phospholipid cyclic phosphatidic acid (CPA) as a potent (binding constant of ∼125 nm) PPARγ antagonist, unlike the PPARγ-activating property of other endogenous ligands. This discovery challenges the paradigm of endogenous ligands as positive regulators and is also surprising in regard to its structure because other lysophospholipids act as PPARγ agonists (62, 63). However, the authors demonstrated that CPA is generated endogenously by phospholipase D2, induces association of PPARγ with NR corepressor (NCoR) 2 due to its cyclic phosphate moiety, and represses PPARγ-dependent adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation in macrophages (61). This finding raises the intriguing question as to which, if any, of the above-described endogenous activators of PPARγ are physiologically antagonized by CPA. It also implicates C18 carboxylic acid-containing phospholipids once more as ligands for PPARs. An overview of the described pathways leading to endogenous ligand generation for PPARγ is shown in Fig. 1B.

Rev-erbα

The NR Rev-erbα is most abundantly expressed in metabolic tissues and is a negative feedback regulator of the circadian clock (64–66). Mice deficient in Rev-erbα display changes in their circadian activity (65). Rev-erbα constitutively represses transcription because it lacks the C-terminal helix that is present in other NR called H12, a domain responsible for coactivator binding (67). Rev-erbα binds as a monomer to target promoters and recruits repression complexes containing the NCoR and HDAC3 (histone deacetylase 3) (67, 68).

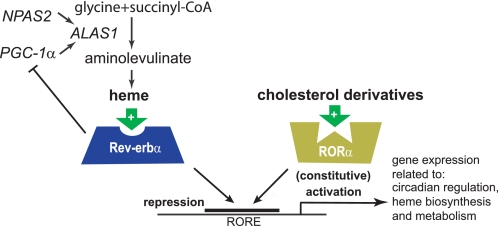

Rev-Erbα was originally cloned as an orphan NR (69, 70). In 2005, the Rev-erbα homolog E75 from Drosophila was shown to contain protoporphyrin IX coordinated to iron (which is commonly referred to as heme) in its LBD (71). Soon after, two groups independently found that heme also binds human Rev-erbα and Rev-erbβ (72, 73). Heme was shown to bind reversibly at a 1:1 stoichiometry, enhance the thermal stability of the protein, and reversibly induce recruitment of the NCoR and HDAC3 by Rev-erbα, thus fulfilling all criteria for an NR ligand (Fig. 2, left). Furthermore, heme depletion or addition of the synthetic analog hemin controlled the expression of the Rev-erbα target gene BMAL1 (72, 73). Heme also mediated the sensitivity of the transcriptional activity of Rev-erbβ to carbon monoxide and nitric oxide (74); whether this is true for Rev-erbα is not clear at this point.

FIGURE 2.

Heme and cholesterol derivatives as endogenous ligands for Rev-erbα and RORα. Transcriptional control of the heme biosynthesis via the regulation of ALAS1 is shown on the left. Both NRs compete for the same ROR-response element (RORE)-binding site for repression or activation of gene transcription.

Although the identification of heme as a Rev-erb ligand came as a surprise, heme itself had been already implicated in circadian regulation. It was shown that heme, as a cofactor for the gas responsive-transcription factor NPAS2 (neuronal PAS domain-containing protein 2) (75), controls the expression of mammalian Period genes mPer1 and mPer2 (76). Also ALAS1 (aminolevulinate synthase 1), the rate-limiting enzyme in circadian heme biosynthesis, was shown to be under the control of NPAS2 (76). Moreover, cellular heme levels oscillated in a circadian manner in NIH3T3 cells (77). It should be pointed out that the interaction of heme with Rev-erbα as a saturable reversible ligand extends the role of heme beyond its function as a gas sensor and identifies an exciting link between the mammalian clock and the control of metabolism by this NR.

Functionally, besides the described roles in circadian regulation, heme-dependent repression of glucose-6-phosphatase by Rev-erbα implicated the newly identified ligand in gluconeogenesis (73). In addition, it was shown that heme controls its own biosynthesis also through Rev-erbα. Binding of heme to Rev-erbα repressed the expression of PGC-1α, a potent inducer of heme biosynthesis (78), which decreased cellular heme concentrations (Fig. 2, left) (79). This negative feedback is in contrast to the heme/NPAS2-mediated induction of ALAS1, and further studies are needed to consolidate these two mechanisms. Hemin has also been shown to be a positive regulator of adipocyte differentiation (80), which could be mediated by binding Rev-erbα, a known regulator of adipogenesis (81, 82). Other Rev-erbα functions, such as lipoprotein expression and bile acid metabolism (83), have not been linked to heme regulation so far.

RORα

RORα was cloned in the early 1990s as the first member of the ROR subfamily and named because of its sequence similarities to the retinoic acid receptor and RXR (84, 85). An excellent review on RORα and ROR subtypes β and γ was published recently (86).

RORα is expressed rather ubiquitously, including cerebellar Purkinje cells, liver, thymus, skeletal muscle, skin, lung, adipose tissue, and kidney (86). An intragenic mutation of RORα found in staggerer mice revealed the involvement of RORα in cerebellar development and glucose and lipid metabolism (87, 88). RORα and RORγ were also shown to regulate the maturation of a specific lineage of helper T cells called Th17 cells (89, 90).

RORα binds DNA as a monomer on ROR-response elements, which consist of the core consensus half-site and an adjacent 5′ A/T-rich sequence (91). This specific binding site can also be bound by Rev-erbα or Rev-erbβ (67), which suggests that it could compete with RORα for occupying these elements (Fig. 2). Interestingly, RORα has been shown to be a constitutive activator of gene transcription, which is in contrast to Rev-erb as a repressor. This dynamic model of activation and repression by ROR and Rev-Erb has been demonstrated for BMAL1 expression (66, 92). Consistent with the effects of Rev-erbα deficiency, staggerer mice also exhibit an abnormal circadian activity pattern (93).

The first potential endogenous ligand for RORα was identified by a crystallographic study showing that RORα, when expressed in baculovirus-infected Sf9 insect cells, integrated cholesterol in its LBD (94). Follow-up studies extended the group of potential ligands to several position 7-, 24-, and 25-substituted cholesterol derivatives and cholesterol sulfate (95, 96). All these sterols were shown to be high-affinity ligands and modulate the interaction of RORα with coactivators (97).

The model of RORα as a cholesterol sensor is intriguing because this NR had been shown to control several genes involved in lipid metabolism (86). Furthermore, it suggested that RORα may not be a constitutively active receptor but rather rendered active by binding of ubiquitously occurring cellular cholesterol and its derivatives. However, RORα expressed in Escherichia coli, without any endogenous sterols present, still exhibited constitutive activity in binding coactivator peptides, suggesting an intrinsic activating property of this NR (86).

It should be pointed out that only a subset of these ligands was able to regulate RORα target gene expression in a receptor-dependent manner (98). This observation indicates that although several different cholesterol-related ligands bind RORα in vivo, only a few are able to modify the receptor's intrinsic activity. Those that bind under physiological conditions without affecting the transcriptional activity of RORα are referred to as silent ligands, a concept evolving from ligands binding several NRs (86, 99, 100). Silent ligands, such as cholesterol or cholesterol sulfate in the case of RORα, may compete with endogenous agonists or inverse agonists, thus adding another level of regulation in the biology of NRs (86). Because the role of cholesterol derivatives in the functional aspects of RORα is still vague, more studies are needed to fully understand their potential as endogenous ligands.

Conclusions

Some of the most effective therapeutic agents available today are derived from endogenous ligands of NRs, with the great example of anti-inflammatory corticosteroids (1). As we have described, many potential candidates have been identified as endogenous ligands for PPAR, Rev-erb, and related receptors. Further research will be required to put them in perspective with regard to their physiological importance and to each other.

A recurring observation is that the cellular metabolism of these ligands is regulated by the corresponding NR, establishing feedback and feed-forward loops to balance NR activation. This may provide clues for the search of physiologically relevant ligands regarding other orphan NRs. Another observation is that the integration of newly identified ligands into the previously known NR physiology is complex, even more with the identification of endogenous antagonists and silent ligands. Cell and animal models in which several different NR ligands are present and can be manipulated will have to be used to consolidate these individual studies.

A way to “dig deeper” for endogenous ligands of the remaining orphan NR should make use of more sophisticated techniques, such as the combination of NR immunoprecipitation from in vivo material and mass spectrometry or crystallographic studies. Once the identification has led to ligands that are generally agreed upon, new therapeutic opportunities that interfere with how NRs work will become evident. We therefore believe that NR research still harbors a great potential for future drug development targeting metabolic diseases and their circadian components.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK45586, DK49780, and DK062434 (Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas; to M. A. L.). This work was also supported by an Emmy-Noether grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SCHU 2546/1-1; to M. S.). This is the third article in the Thematic Minireview Series on Nuclear Receptors in Biology and Diseases. This minireview will be reprinted in the 2010 Minireview Compendium, which will be available in January, 2011.

- NR

- nuclear receptor

- LBD

- ligand-binding domain

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- ROR

- retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor

- RXR

- retinoid X receptor

- OEA

- oleoylethanolamide

- FAS

- fatty acid synthase

- 16:0/18:1 GPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoly-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- TZD

- thiazolidinedione

- XOR

- xanthine oxidoreductase

- RetSat

- retinol saturase

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- 5-HT

- 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin)

- CPA

- cyclic phosphatidic acid

- NCoR

- nuclear receptor corepressor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mangelsdorf D. J., Thummel C., Beato M., Herrlich P., Schutz G., Umesono K., Blumberg B., Kastner P., Mark M., Chambon P., Evans R. M. (1995) Cell 83, 835–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranda A., Pascual A. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 1269–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perissi V., Rosenfeld M. G. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 542–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janowski B. A., Willy P. J., Devi T. R., Falck J. R., Mangelsdorf D. J. (1996) Nature 383, 728–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delerive P., Furman C., Teissier E., Fruchart J., Duriez P., Staels B. (2000) FEBS Lett. 471, 34–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto K. R., Alberts B. M. (1972) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69, 2105–2109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuels H. H., Tsai J. S., Casanova J. (1974) Science 184, 1188–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petkovich M., Brand N. J., Krust A., Chambon P. (1987) Nature 330, 444–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giguere V., Ong E. S., Segui P., Evans R. M. (1987) Nature 330, 624–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brumbaugh P. F., Haussler M. R. (1973) Life Sci. 13, 1737–1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortlund E. A., Lee Y., Solomon I. H., Hager J. M., Safi R., Choi Y., Guan Z., Tripathy A., Raetz C. R., McDonnell D. P., Moore D. D., Redinbo M. R. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y., Choi M., Cavey G., Daugherty J., Suino K., Kovach A., Bingham N. C., Kliewer S. A., Xu H. E. (2005) Mol. Cell 17, 491–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krylova I. N., Sablin E. P., Moore J., Xu R. X., Waitt G. M., MacKay J. A., Juzumiene D., Bynum J. M., Madauss K., Montana V., Lebedeva L., Suzawa M., Williams J. D., Williams S. P., Guy R. K., Thornton J. W., Fletterick R. J., Willson T. M., Ingraham H. A. (2005) Cell 120, 343–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakravarthy M. V., Lodhi I. J., Yin L., Malapaka R. R., Xu H. E., Turk J., Semenkovich C. F. (2009) Cell 138, 476–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nolte R. T., Wisely G. B., Westin S., Cobb J. E., Lambert M. H., Kurokawa R., Rosenfeld M. G., Willson T. M., Glass C. K., Milburn M. V. (1998) Nature 395, 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallenborg P., Jørgensen C., Petersen R. K., Feddersen S., Araujo P., Markt P., Langer T., Furstenberger G., Krieg P., Koppen A., Kalkhoven E., Madsen L., Kristiansen K. (2010) Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 4077–4091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schopfer F. J., Cole M. P., Groeger A. L., Chen C. S., Khoo N. K., Woodcock S. R., Golin-Bisello F., Motanya U. N., Li Y., Zhang J., Garcia-Barrio M. T., Rudolph T. K., Rudolph V., Bonacci G., Baker P. R., Xu H. E., Batthyany C. I., Chen Y. E., Hallis T. M., Freeman B. A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12321–12333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forman B. M., Tontonoz P., Chen J., Brun R. P., Spiegelman B. M., Evans R. M. (1995) Cell 83, 803–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell-Parikh L. C., Ide T., Lawson J. A., McNamara P., Reilly M., FitzGerald G. A. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 112, 945–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narala V. R., Adapala R. K., Suresh M. V., Brock T. G., Peters-Golden M., Reddy R. C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22067–22074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy J. K., Hashimoto T. (2001) Annu. Rev. Nutr. 21, 193–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kersten S., Seydoux J., Peters J. M., Gonzalez F. J., Desvergne B., Wahli W. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 1489–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barter P. J., Rye K. A. (2008) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen E. D., MacDougald O. A. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 885–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Meer D. L., Degenhardt T., Väisänen S., de Groot P. J., Heinäniemi M., de Vries S. C., Müller M., Carlberg C., Kersten S. (2010) Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 2839–2850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefterova M. I., Zhang Y., Steger D. J., Schupp M., Schug J., Cristancho A., Feng D., Zhuo D., Stoeckert C. J., Jr., Liu X. S., Lazar M. A. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 2941–2952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen R., Pedersen T. A., Hagenbeek D., Moulos P., Siersbaek R., Megens E., Denissov S., Børgesen M., Francoijs K. J., Mandrup S., Stunnenberg H. G. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 2953–2967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forman B. M., Chen J., Evans R. M. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4312–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kliewer S. A., Sundseth S. S., Jones S. A., Brown P. J., Wisely G. B., Koble C. S., Devchand P., Wahli W., Willson T. M., Lenhard J. M., Lehmann J. M. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4318–4323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krey G., Braissant O., L'Horset F., Kalkhoven E., Perroud M., Parker M. G., Wahli W. (1997) Mol. Endocrinol. 11, 779–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu K., Bayona W., Kallen C. B., Harding H. P., Ravera C. P., McMahon G., Brown M., Lazar M. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 23975–23983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devchand P. R., Keller H., Peters J. M., Vazquez M., Gonzalez F. J., Wahli W. (1996) Nature 384, 39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziouzenkova O., Perrey S., Asatryan L., Hwang J., MacNaul K. L., Moller D. E., Rader D. J., Sevanian A., Zechner R., Hoefler G., Plutzky J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2730–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruby M. A., Goldenson B., Orasanu G., Johnston T. P., Plutzky J., Krauss R. M. (2010) J. Lipid Res. 51, 2275–2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu J., Gaetani S., Oveisi F., Lo Verme J., Serrano A., Rodríguez De Fonseca F., Rosengarth A., Luecke H., Di Giacomo B., Tarzia G., Piomelli D. (2003) Nature 425, 90–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LoVerme J., Guzmán M., Gaetani S., Piomelli D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22815–22818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarthy M. V., Pan Z., Zhu Y., Tordjman K., Schneider J. G., Coleman T., Turk J., Semenkovich C. F. (2005) Cell Metab. 1, 309–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan C. Y., Pan J., Usuda N., Yeldandi A. V., Rao M. S., Reddy J. K. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15639–15645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pyper S. R., Viswakarma N., Yu S., Reddy J. K. (2010) Nucl. Recept. Signal. 8, e002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wray J. A., Sugden M. C., Zeldin D. C., Greenwood G. K., Samsuddin S., Miller-Degraff L., Bradbury J. A., Holness M. J., Warner T. D., Bishop-Bailey D. (2009) PLoS One 4, e7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tontonoz P., Hu E., Spiegelman B. M. (1994) Cell 79, 1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricote M., Li A. C., Willson T. M., Kelly C. J., Glass C. K. (1998) Nature 391, 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akiyama T. E., Sakai S., Lambert G., Nicol C. J., Matsusue K., Pimprale S., Lee Y. H., Ricote M., Glass C. K., Brewer H. B., Jr., Gonzalez F. J. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 2607–2619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lefterova M. I., Steger D. J., Zhuo D., Qatanani M., Mullican S. E., Tuteja G., Manduchi E., Grant G. R., Lazar M. A. (2010) Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 2078–2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lehmann J. M., Moore L. B., Smith-Oliver T. A., Wilkison W. O., Willson T. M., Kliewer S. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12953–12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kliewer S. A., Lenhard J. M., Willson T. M., Patel I., Morris D. C., Lehmann J. M. (1995) Cell 83, 813–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagy L., Tontonoz P., Alvarez J. G., Chen H., Evans R. M. (1998) Cell 93, 229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davies S. S., Pontsler A. V., Marathe G. K., Harrison K. A., Murphy R. C., Hinshaw J. C., Prestwich G. D., Hilaire A. S., Prescott S. M., Zimmerman G. A., McIntyre T. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16015–16023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schopfer F. J., Lin Y., Baker P. R., Cui T., Garcia-Barrio M., Zhang J., Chen K., Chen Y. E., Freeman B. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2340–2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baker P. R., Schopfer F. J., Sweeney S., Freeman B. A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 11577–11582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexander R. L., Wright M. W., Gorczynski M. J., Smitherman P. K., Akiyama T. E., Wood H. B., Berger J. P., King S. B., Morrow C. S. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 492–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J. B., Wright H. M., Wright M., Spiegelman B. M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 4333–4337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tzameli I., Fang H., Ollero M., Shi H., Hamm J. K., Kievit P., Hollenberg A. N., Flier J. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36093–36102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheung K. J., Tzameli I., Pissios P., Rovira I., Gavrilova O., Ohtsubo T., Chen Z., Finkel T., Flier J. S., Friedman J. M. (2007) Cell Metab. 5, 115–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schupp M., Lefterova M. I., Janke J., Leitner K., Cristancho A. G., Mullican S. E., Qatanani M., Szwergold N., Steger D. J., Curtin J. C., Kim R. J., Suh M. J., Suh M., Albert M. R., Engeli S., Gudas L. J., Lazar M. A. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1105–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moise A. R., Lobo G. P., Erokwu B., Wilson D. L., Peck D., Alvarez S., Domínguez M., Alvarez R., Flask C. A., de Lera A. R., von Lintig J., Palczewski K. (2010) FASEB J. 24, 1261–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagaoka-Yasuda R., Matsuo N., Perkins B., Limbaeck-Stokin K., Mayford M. (2007) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waku T., Shiraki T., Oyama T., Maebara K., Nakamori R., Morikawa K. (2010) EMBO J. 26, 3395–3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Srinivasan S., Sadegh L., Elle I. C., Christensen A. G., Faergeman N. J., Ashrafi K. (2008) Cell Metab. 7, 533–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Auwerx J. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 282, G581–G585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsukahara T., Tsukahara R., Fujiwara Y., Yue J., Cheng Y., Guo H., Bolen A., Zhang C., Balazs L., Re F., Du G., Frohman M. A., Baker D. L., Parrill A. L., Uchiyama A., Kobayashi T., Murakami-Murofushi K., Tigyi G. (2010) Mol. Cell 39, 421–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McIntyre T. M., Pontsler A. V., Silva A. R., St. Hilaire A., Xu Y., Hinshaw J. C., Zimmerman G. A., Hama K., Aoki J., Arai H., Prestwich G. D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 131–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsukahara T., Tsukahara R., Yasuda S., Makarova N., Valentine W. J., Allison P., Yuan H., Baker D. L., Li Z., Bittman R., Parrill A., Tigyi G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3398–3407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lazar M. A., Hodin R. A., Darling D. S., Chin W. W. (1989) Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 1128–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Preitner N., Damiola F., Lopez-Molina L., Zakany J., Duboule D., Albrecht U., Schibler U. (2002) Cell 110, 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yin L., Wang J., Klein P. S., Lazar M. A. (2006) Science 311, 1002–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harding H. P., Lazar M. A. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 4791–4802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yin L., Lazar M. A. (2005) Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 1452–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lazar M. A., Jones K. E., Chin W. W. (1990) DNA Cell Biol. 9, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miyajima N., Horiuchi R., Shibuya Y., Fukushige S., Matsubara K., Toyoshima K., Yamamoto T. (1989) Cell 57, 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reinking J., Lam M. M., Pardee K., Sampson H. M., Liu S., Yang P., Williams S., White W., Lajoie G., Edwards A., Krause H. M. (2005) Cell 122, 195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raghuram S., Stayrook K. R., Huang P., Rogers P. M., Nosie A. K., McClure D. B., Burris L. L., Khorasanizadeh S., Burris T. P., Rastinejad F. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 1207–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yin L., Wu N., Curtin J. C., Qatanani M., Szwergold N. R., Reid R. A., Waitt G. M., Parks D. J., Pearce K. H., Wisely G. B., Lazar M. A. (2007) Science 318, 1786–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marvin K. A., Reinking J. L., Lee A. J., Pardee K., Krause H. M., Burstyn J. N. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 7056–7071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dioum E. M., Rutter J., Tuckerman J. R., Gonzalez G., Gilles-Gonzalez M. A., McKnight S. L. (2002) Science 298, 2385–2387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaasik K., Lee C. C. (2004) Nature 430, 467–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rogers P. M., Ying L., Burris T. P. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 368, 955–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Handschin C., Lin J., Rhee J., Peyer A. K., Chin S., Wu P. H., Meyer U. A., Spiegelman B. M. (2005) Cell 122, 505–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu N., Yin L., Hanniman E. A., Joshi S., Lazar M. A. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 2201–2209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen J. J., London I. M. (1981) Cell 26, 117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fontaine C., Dubois G., Duguay Y., Helledie T., Vu-Dac N., Gervois P., Soncin F., Mandrup S., Fruchart J. C., Fruchart-Najib J., Staels B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37672–37680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang J., Lazar M. A. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 2213–2220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duez H., Staels B. (2009) J. Appl. Physiol. 107, 1972–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Becker-André M., André E., DeLamarter J. F. (1993) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 194, 1371–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Giguère V., Tini M., Flock G., Ong E., Evans R. M., Otulakowski G. (1994) Genes Dev. 8, 538–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Solt L. A., Griffin P. R., Burris T. P. (2010) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 21, 204–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lau P., Fitzsimmons R. L., Raichur S., Wang S. C., Lechtken A., Muscat G. E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18411–18421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hamilton B. A., Frankel W. N., Kerrebrock A. W., Hawkins T. L., FitzHugh W., Kusumi K., Russell L. B., Mueller K. L., van Berkel V., Birren B. W., Kruglyak L., Lander E. S. (1996) Nature 379, 736–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang X. O., Pappu B. P., Nurieva R., Akimzhanov A., Kang H. S., Chung Y., Ma L., Shah B., Panopoulos A. D., Schluns K. S., Watowich S. S., Tian Q., Jetten A. M., Dong C. (2008) Immunity 28, 29–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ivanov I. I., McKenzie B. S., Zhou L., Tadokoro C. E., Lepelley A., Lafaille J. J., Cua D. J., Littman D. R. (2006) Cell 126, 1121–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Giguère V., McBroom L. D., Flock G. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 2517–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sato T. K., Panda S., Miraglia L. J., Reyes T. M., Rudic R. D., McNamara P., Naik K. A., FitzGerald G. A., Kay S. A., Hogenesch J. B. (2004) Neuron 43, 527–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Akashi M., Takumi T. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 441–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kallen J. A., Schlaeppi J. M., Bitsch F., Geisse S., Geiser M., Delhon I., Fournier B. (2002) Structure 10, 1697–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kallen J., Schlaeppi J. M., Bitsch F., Delhon I., Fournier B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 14033–14038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bitsch F., Aichholz R., Kallen J., Geisse S., Fournier B., Schlaeppi J. M. (2003) Anal. Biochem. 323, 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang Y., Kumar N., Crumbley C., Griffin P. R., Burris T. P. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1801, 917–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang Y., Kumar N., Solt L. A., Richardson T. I., Helvering L. M., Crumbley C., Garcia-Ordonez R. D., Stayrook K. R., Zhang X., Novick S., Chalmers M. J., Griffin P. R., Burris T. P. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5013–5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yuan X., Ta T. C., Lin M., Evans J. R., Dong Y., Bolotin E., Sherman M. A., Forman B. M., Sladek F. M. (2009) PLoS One 4, e5609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Horner M. A., Pardee K., Liu S., King-Jones K., Lajoie G., Edwards A., Krause H. M., Thummel C. S. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 2711–2716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.