Abstract

Spider silks are spun from concentrated solutions of spidroin proteins. The appropriate timing of spidroin assembly into organized fibers must be highly regulated to avoid premature fiber formation. Chemical and physical signals presented to the silk proteins as they pass from the ampulle and through the tapered duct include changes in ionic environment and pH as well as the introduction of shear forces. Here, we show that the N-terminal domain of spidroins from the major ampullate gland (MaSp-NTDs) for both Nephila and Latrodectus spiders associate noncovalently as homodimers. The MaSp-NTDs are highly pH-responsive and undergo a structural transition in the physiological pH range of the spider duct. Tryptophan fluorescence of the MaSp-NTDs reveals a change in conformation when pH is decreased, and the pH at which the transition occurs is determined by the amount and type of salt present. Size exclusion chromatography and pulldown assays both indicate that the lower pH conformation is associated with a significantly increased MaSp-NTD homodimer stability. By transducing the duct pH signal into specific protein-protein interactions, this conserved spidroin domain likely contributes significantly to the silk-spinning process. Based on these results, we propose a model of spider silk assembly dynamics as mediated through the MaSp-NTD.

Keywords: Protein Assembly, Protein Conformation, Protein Domains, Protein Self-assembly, Protein-Protein Interactions, Fiber Assembly, Spider Silk, Spidroin

Introduction

Spider silks are protein-based fibers with remarkable mechanical qualities. Perhaps even more impressive is the spinning process in which the spider silk proteins (spidroins) are assembled from a highly soluble storage state into a well ordered and insoluble fiber. Spiders can produce up to seven different types of silk each composed of different spidroin proteins and spun from distinct abdominal glands (1). Here, the spinning process of the major ampullate gland of Nephila spiders will be summarized as an example, but many of its features are common to other spider silks and are even analogous to moth and butterfly silks.

Prior to spinning, the spidroins are stored in the gland at a very high concentration (∼300 g liter−1) that causes them to adopt a liquid crystalline arrangement (2, 3). The secondary structure of the stored spidroins is a mix of random coil and α-helices (4). When there is a demand for silk fiber, the spidroin solution is drawn down a long and tapered duct in which the proteins experience a gradual change in their chemical environment (5). Along the length of the duct, Na+ drops from 3.1 mg g−1 dry weight in the ampulle (where the spidroins are stored) to 0.3 mg g−1 in the fiber, and K+ increases from 0.75 to 2.9 mg g−1 (6). Phosphate concentration also increases at least 5-fold, whereas flow velocity and shear force increase (especially near the end) because of the tapered geometry of the duct (5, 7). Importantly, pH drops from 7.2 in the storage region to 6.3 in the first 0.5 mm of the duct and reaches an unknown value by the end of the ∼20-mm duct (8). Collectively, these chemical and physical forces induce the spidroin molecules to align with the direction of flow, form β-sheets, and partition out of the aqueous phase to form a solid fiber (9, 10).

The fiber produced from the major ampullate gland is called dragline silk, and it is used in the main structural elements of an orb web and also as a hanging lifeline. Its primary protein constituents are major ampullate spidroins 1 and 2 (MaSp1 and MaSp2) (11–13). These proteins are highly repetitive molecules having a 30–40-amino acid consensus sequence repeated ∼100 times in tandem (14). Flanking this repeat array are short nonrepetitive N- and C-terminal domains (NTDs2 and CTDs) of ∼155 and ∼100 amino acids, respectively (12, 15). The CTDs are conserved, not just among major ampullate spidroins but among all fiber-forming spidroins, as are the N-terminal domains for all spidroins for which 5′ gene sequences are currently known (16). Because these domains have been conserved over hundreds of millions of years of spider evolution, they likely confer an important function on spidroin proteins. In studies of recombinant partial spidroins, it has been clearly established that the CTDs of major ampullate spidroins (generically MaSp-CTDs) play a significant role in promoting and coordinating spidroin assembly (17, 18). It does this, in part, by forming a homodimer that may involve a disulfide bond between the individual MaSp-CTDs (19, 20).

However, less is known about the contribution of MaSp-NTDs (generically referring to MaSp1 and MaSp2 of any species) to spidroin function. Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence of MaSp-NTD has led to predictions that its secondary structure consists mainly of five α-helices (15). It is also predicted that a signal peptide is present on MaSp-NTD that directs secretion of the spidroin into the gland lumen and is likely proteolytically removed during secretion. CD spectra performed by Rising et al. (21) corroborates the predominance of α-helices, and size exclusion chromatography by Hedhammar et al. (19) has suggested that MaSp-NTD can homodimerize (19, 21). Recently, Askarieh et al. (22) presented a crystal structure of an Euprosthenops MaSp-NTD dimer and biochemical data indicating the NTD undergoes pH-induced conformational change. In this study, we examine recombinant Nephila and Latrodectus MaSp-NTD proteins to further elucidate functionally relevant biochemical features. We show that MaSp-NTDs from Nephila and Latrodectus spiders also change conformation in response to the pH decrease that occurs in the silk gland and that this change is sensitive to the ionic environment. In addition, the conformational change leads to a stabilization of MaSp-NTD dimerization that likely has functional significance to the fiber-spinning process.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction, Protein Expression, and Purification

Three MaSp N-terminal domains (MaSp1A-NTD and MaSp2-NTD from Nephila clavipes and MaSp1-NTD from L. mactans) were isolated from N. clavipes or Latrodectus mactans genomic DNA by PCR with homolog-specific primer sets. The forward primer for each homolog begins at the predicted signal peptide cleavage site such that the recombinant proteins will resemble mature, native MaSp-NTD. Each primer set included a stop codon at the end of the MaSp-NTD and a 5′ XmaI site and 3′ XhoI site for subsequent ligation into pGEX-6P-2 plasmid (GE Healthcare). BL21 cells harboring the plasmids were cultured, and protein expression was induced with 0.25 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. Proteins were purified from sonication lysates by affinity to glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare), and affinity tags were removed by PreScission protease digestion. The purified MaSp-NTDs were eluted from the column and subsequently concentrated on a 10-kDa cutoff Amicon (Millipore) ultracentrifugal filtration device. After GST removal, vector-derived “GPLGSPGIPG” remained on the N-terminal end of the MaSp-NTDs (supplemental Fig. S1). The purified proteins were assayed by SDS-PAGE with staining by Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye.

Tryptophan Fluorescence

Measurements were performed in a spectrofluorometer (Photon Technologies International model 814) using a 1 × 1-cm quartz cuvette. Protein sample was excited at 295 nm, and emission spectra were taken from 310 to 370 nm at 2-nm steps. For pH titrations, the MaSp-NTD protein was diluted to ∼3 μm into 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm MES buffer, 0.1 μm fluorescein, with 20, 100, or 200 mm NaCl, pH 7.5 or 5.0. Each titration began with a reading of the pH 7.5 buffer with protein in a constantly stirred cell. A volume (which varied between steps to give a constant 0.1 pH unit change per step) was removed, and an equal volume of pH 5.0 buffer with same protein and salt concentration was added to decrease pH but leave all other conditions unchanged. At each step, Trp fluorescence and fluorescein fluorescence readings were taken. This was repeated with increasing volumes of replacement until the pH reached 5.0. Fluorescein was used as a pH probe by monitoring the ratio of emission intensities at 508 nm when excited with 450 and 490 nm of light. Calibration was performed at 0.5 pH unit steps from pH 5.0 to 7.5 in the same buffer used for titrations and fitted to a sigmoidal regression. For readings other than the pH titrations, MaSp-NTD proteins were diluted into 1 ml of separate buffers prepared at 0.5 pH unit steps, mixed by pipetting, and read. The presence of fluorescein had no significant effect on MaSp-NTD Trp fluorescence (supplemental Fig. S2).

Size Exclusion Chromatography

Sephacryl S-100 (GE Healthcare) resin was packed into a 1.6-cm diameter by 27-cm height column with a total volume of 55 ml. The running buffers were 10 mm MES, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0 or 5.5, with NaCl of 0, 100, 500, or 1000 mm. A molecular mass standard set consisting of vitamin B12 (1.3 kDa), RNase A (13.7 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), and ovalbumin (43 kDa) was chromatographed under each buffer condition used. The MaSp-NTD samples were 200 μm protein in 100 μl of appropriate running buffer and were allowed to equilibrate with the buffer for 5 min prior to injection onto the column. The flow rate was 0.5 ml min−1, and fractions were collected every 1.5 ml. These fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE to confirm that the UV absorbing peaks were indeed MaSp-NTD protein. The molecular mass estimates of MaSp-NTD oligomers were calculated by regression on the buffer appropriate marker set.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Measurements were performed on a Brookhaven Instruments 90Plus particle sizer and analyzed with accompanying software. Protein samples were at a concentration of 0.8 g liter−1 (53 μm) in 300 μl of buffer (10 mm MES, 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm citrate, 20 mm NaCl, variable pH). Protein samples and buffers were all thoroughly filtered to remove dust. After measurement at 20 mm NaCl, concentrated NaCl was added to a final concentration of 100 mm, and measurements were performed again. Each sample was measured at a 90° angle for 3 min in triplicate.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

CD spectra were recorded in a Jasco J-810 CD spectrophotometer equipped with a Peltier temperature control unit. The quartz cuvette had a 1-mm path length and 300-μl internal volume. Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein was 20 μm in buffer with 10 mm NaH2PO4 at pH 7.0 or 5.5 with either 0 or 500 mm NaF. NaF was substituted for NaCl due to the lower UV absorbance. For each melt/anneal experiment, CD spectra from 260 to 190 nm were first recorded at 20 °C. The sample was heated at 5 °C min−1 to 90 °C and then cooled at the same rate down to 20 °C. All spectra presented are the average of three scans and are blanked against the appropriate buffer.

Pulldowns

MaSp-NTD proteins (Nc.MaSp1A-NTD, Nc.MaSp2-NTD, and Lm.MaSp1-NTD) were covalently coupled to Affi-Gel® 10 resin (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer's instructions at a protein density of 3.5 mg protein ml−1 of resin. BSA was coupled separately at 5.0 mg protein ml−1 resin. The protein-coupled resins were washed thoroughly with buffer containing 0.5 m NaCl, pH 7.0, to wash away any noncovalently bound proteins. Pulldowns were performed in 10 mm MES, 10 mm HEPES at varied pH (5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, or 7.0) and varied NaCl (20, 100, or 200 mm) for a total of 15 conditions. In a total volume of 30 μl, 5 μl of resin bearing 17.5 μg of immobilized MaSp-NTD and 10 μg (22 μm) of free MaSp-NTD of the same type were present. This was incubated overnight at room temperature to allow free dimers to dissociate and permit dimerization with immobilized protein. Next, the volume was increased to 100 μl with binding buffer (matching the pH and salt concentration of that treatment), mixed gently, incubated for 30 s, centrifuged (2000 rpm, 15 s), and the supernatant was removed. This was repeated twice for a total of three washes. The washed resin was then resuspended in 80 μl of elution buffer (10 mm MES, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, with 200 mm NaCl and 1% SDS) and incubated for 15 min with periodic agitation. The elution was removed from the resin and BCA assayed to determine the amount of MaSp-NTD pulled down. The pulldowns of free MaSp-NTD using immobilized MaSp-NTD were performed in triplicate. Pulldowns of free MaSp-NTD using immobilized BSA under all 15 conditions were also performed as a control, and mock pulldowns (no free MaSp-NTD) were performed for each resin to ensure no immobilized protein was released from the resin. SDS-PAGE of the eluted protein was performed to ensure that only MaSp-NTD protein was present in the elution. Pulldowns with an extended wash time course were initiated by overnight incubation of an appropriately scaled binding reaction at pH 5.5 with 20 mm NaCl to promote maximal binding (240 μl of resin bearing immobilized Nc.MaSp1A-NTD and 480 μg (22 μm) of free Nc.MaSp1A-NTD in 1.14 ml total volume). The resin was subsequently washed with pH 5.5 buffer three times to remove unbound protein and distributed into 48 tubes. Buffer (2 ml) at the appropriate pH containing 20 mm NaCl was added, and the resin was rotated for variable time periods before elution of remaining protein.

RESULTS

Recombinant Expression and Purification of MaSp-NTD Proteins

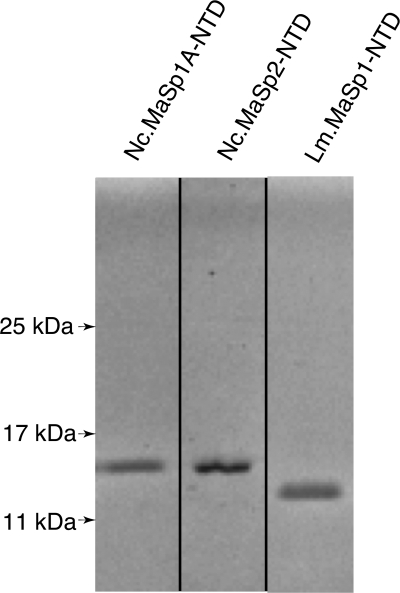

We have cloned and overexpressed the NTDs of N. clavipes MaSp1A and MaSp2 (Nc.MaSp1A and Nc.MaSp2, respectively) and of L. mactans MaSp1 (Lm.MaSp1) as GST fusions in Escherichia coli (see “Experimental Procedures” and supplemental Fig. S1 for details). The two N. clavipes MaSp-NTDs were based on our previously isolated sequences (23) and that of L. mactans on sequences isolated as part of this study. Interestingly, the L. mactans MaSp1-NTD differs by only a single conservative amino acid change (Leu to Ile) from MaSp1 locus 1 (L1) and locus 2 (L2) from Latrodectus hesperus (24). MaSp-NTD proteins were purified by glutathione-Sepharose affinity chromatography and subsequent removal of the affinity tag resulting in recombinant proteins with >95% homogeneity (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

SDS-PAGE of purified MaSp-NTD proteins. Nc.MaSp1A-NTD (15.0 kDa) (1st lane); Nc.MaSp2-NTD (14.9 kDa) (2nd lane), and Lm.MaSp1-NTD (14.0 kDa) (3rd lane) were run on a 15% acrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie Blue dye. Marker sizes are indicated to the left. 1st and 3rd lanes are nonadjacent lanes from the same gel, and 2nd lane is from a separate gel.

Tryptophan Fluorescence

All three MaSp-NTDs examined in this paper have a single tryptophan residue at position 5 or 6 after the predicted signal peptide cleavage site (supplemental Fig. S1). This amino acid fluoresces when excited with light at 295 nm. The fluorescent emission varies in intensity and wavelength depending on the local environment surrounding the Trp side chain. If a Trp residue is solvent-exposed, it will emit fewer photons and at a longer (less energetic) wavelength compared with a Trp residue in a more hydrophobic context. Therefore, Trp fluorescence can be used as a sensor for local structural changes.

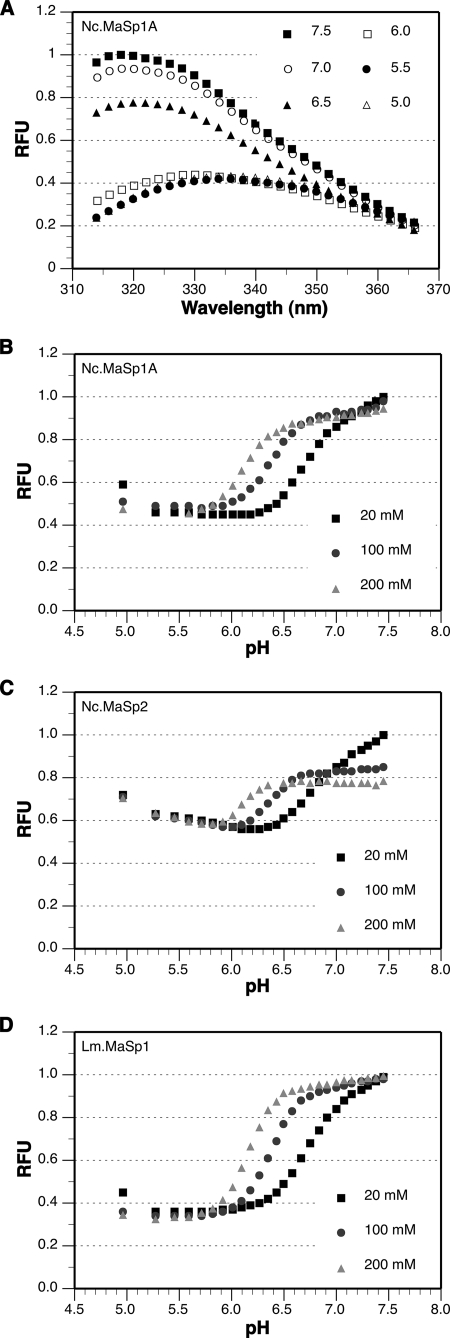

We examined the Trp fluorescence of our recombinant Nc.MaSp1A-NTD under a variety of buffer conditions, with particular emphasis on those that are known to change along the major ampullate duct (pH, [Na+], [K+], phosphate). Trp fluorescence changes dramatically when the pH is titrated from 7.5 to 5.0 (Fig. 2A), decreasing in intensity and red-shifting indicating that the Trp residue becomes more solvent-exposed at lower pH. Trp fluorescence is unaffected by the 10 non-native amino acids at the N-terminal end of the MaSp1A-NTD as the spectra obtained are virtually identical when four different non-native amino acids are present (supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 2.

Trp fluorescence of MaSp-NTDs. A, emission spectra for Nc.MaSp1A-NTD in 100 mm NaCl at pH ranging from 7.5 to 5.0. B–D, emission spectra intensity summation (i.e. total fluorescence) at each pH and salt condition for Nc.MaSp1A-NTD (B), Nc.MaSp2-NTD (C), and Lm.MaSp1-NTD (D). Values are normalized against the highest intensity reading for each MaSp-NTD protein. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

Interestingly, the ionic strength of the buffer had an impact on the change in Trp fluorescence during the pH titration. High NaCl concentrations caused the Trp residue to remain buried at a more acidic pH compared with lower salt buffers (Fig. 2B) indicating that increased ionic strength stabilizes the more fluorescent conformation. Similar results were obtained for the Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein using a variety of buffer systems (MES/HEPES, phosphate, and Tris/citrate). The conformational change occurred in less than 1 min under all conditions as this was the amount of time between mixing the protein and taking the first reading, and no further conformational change was observed in any subsequent readings. As evidence that this conformational change is not specific to the Nc.MaSp1A-NTD, the Trp fluorescence spectra for both Nc.MaSp2-NTD and Lm.MaSp1-NTD, including the salt effect, are essentially the same as that for Nc.MaSp1A-NTD (Fig. 2, C and D, respectively).

In addition to NaCl, we assessed Nc.MaSp1A-NTD Trp fluorescence in buffers containing KCl and sodium phosphate as well as mixtures of NaCl and KCl at various concentrations and pH. In all cases, the trends are similar to that observed with NaCl in that overall fluorescence decreases as pH is lowered and increased ionic strength shifts the pH at which the conformational change occurs toward more acidic values (supplemental Fig. S4A and data not shown). In contrast, MgCl2 and CaCl2 had a more potent effect on Trp fluorescence (supplemental Fig. S4A). Both divalent cations appear to have stabilized the more fluorescent conformation across the range of pH 7.0 to 6.0 with only a moderate decrease in Trp fluorescence at pH 5.5.

Size Exclusion Chromatography

Hedhammar et al. (19) have demonstrated that the N-terminal domain of Euprosthenops australis MaSp1 (Ea.MaSp1-NTD) elutes during size exclusion chromatography (SEC) at pH 7.4 and low ionic strength at a mass consistent with a homodimer. We wished to determine whether the three MaSp-NTDs under study here would behave similarly in a low ionic strength buffer and whether the pH and ionic strength effects we observed for Trp fluorescence would translate to alterations in the MaSp-NTD oligomeric state.

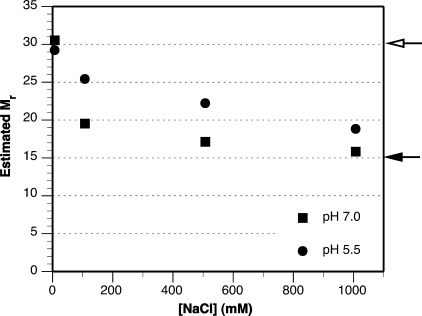

When subjected to SEC in a low ionic strength buffer, pH 7.0, Nc.MaSp1A-NTD, Nc.MaSp2-NTD, and Lm.MaSp1-NTD all eluted at molecular masses consistent with homodimerization (estimated at 30.5, 27.8, and 33.5 kDa, respectively, where monomer molecular masses are 15.0, 14.9, and 14.0 kDa, respectively). Similarly, at pH 5.5 with no salt, Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein also eluted as a homodimer. To evaluate the effect of elevated salt concentrations, Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein was subjected to SEC in buffers containing 100, 500, or 1000 mm NaCl at pH 7.0 and 5.5. Under all conditions, the Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein eluted as a single peak, and oligomeric states larger than a dimer were never observed (supplemental Fig. S5). However, the estimated mass was either intermediate to monomer and dimer sizes (for moderate ionic strength buffers) or very close to monomer size (for high ionic strength buffers; Fig. 3). We interpret these intermediate molecular mass estimates to indicate that Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein is entering the column as a dimer but, upon experiencing a threshold amount of dilution, becomes monomeric and remains so for the remainder of the separation. For both pH 5.5 and 7.0, higher amounts of NaCl in the running buffer resulted in a more monomeric molecular mass estimate suggesting that increased NaCl destabilizes the self-interaction of MaSp-NTDs. However, much higher amounts of NaCl were required to shift the elution profile for Nc.MaSp1A-NTD toward monomer size at pH 5.5 than at pH 7.0 (e.g. the pH 5.5 with 1000 mm NaCl sample elutes similarly to the pH 7.0 with 100 mm NaCl sample). This could indicate the dimer association is stronger at pH 5.5. It is important to note that the elution profile of the molecular mass standards was determined under all eight buffer conditions and was unaffected by the changes in pH or ionic strength.

FIGURE 3.

SEC of Nc.MaSp1A-NTD. Nc.MaSp1A-NTD was chromatographed in buffers at pH 7.0 or 5.5 and containing 0, 100, 500, or 1000 mm NaCl. Molecular masses (in kDa) are based on the SEC elution profile compared with molecular mass standards. Closed and open arrows indicate the predicted monomer and dimer molecular masses, respectively.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Recently, Askarieh et al. (22) reported that Ea.MaSp1-NTD aggregates into particles of about 800 nm diameter in a pH-dependent manner (∼pH 6). We performed dynamic light scattering measurements between pH 4.0 and 7.5 to determine whether Nc.MaSp1A-NTD and Lm.MaSp1-NTD behave similarly. Our results show that, unlike Ea.MaSp1-NTD, neither of the proteins aggregate into large assemblies at any pH or salt concentration tested (supplemental Fig. S6). To ensure that this lack of aggregation was not an experimental artifact, we also generated an Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein in which the 10 N-terminal non-native residues of our own constructs were replaced with the same four non-native residues (GSGN) present on Ea.MaSp1-NTD (Nc.MaSp1A-NTD-Mut). The change in non-native residues had no effect, and no large scale aggregation was observed (supplemental Fig. S6).

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Given the effects of pH and ionic strength on MaSp-NTD conformation and dimerization, it was of interest to probe the impact of these treatments on secondary structure. Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein was examined by CD spectroscopy in buffers at pH 5.5 and 7.0 with either low (0 mm) or high (500 mm NaF) salt. When samples were examined at 20 °C, the spectra were essentially identical for all buffer conditions and consistent with predominantly α-helical secondary structure. The samples were also heated to 90 °C and then cooled back to 20 °C. Under all conditions, Nc.MaSp1A-NTD protein was able to refold upon cooling and produced spectra essentially identical to the pre-melt spectra (supplemental Fig. S7).

Pulldowns

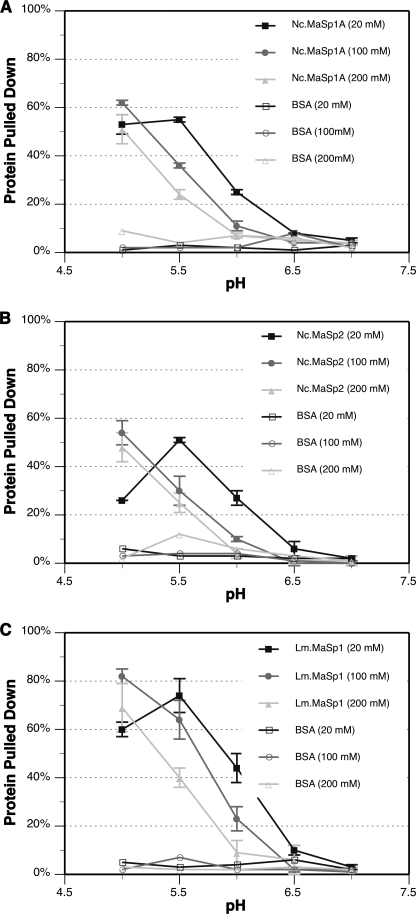

To further characterize the influence of pH and ionic strength on MaSp-NTD dimer stability, we performed pulldown experiments. MaSp-NTD proteins were covalently coupled to a resin under conditions that should favor a wide spacing of immobilized monomers (low protein concentration, 80 mm CaCl2, pH 7.5) and used to capture free MaSp-NTDs of the same type from solution. The mixed free and resin-immobilized MaSp-NTD proteins were incubated overnight to ensure that dimers in free solution would have sufficient time to dissociate then dimerize with resin-immobilized monomers.

The pulldowns were done under 15 different conditions that included five pH steps and three NaCl concentrations. At pH 7.0 or 6.5, almost no free MaSp-NTD protein is pulled down for all three NaCl conditions and for each of the three homologs tested (Fig. 4). Although dimers are expected to form at pH 7.0, because the association is not particularly strong, they dissociate during the wash steps and are therefore not present in the eluted protein fraction. In contrast, at pH 5.5 and 5.0 a significant fraction (ranging from 25 to 80%) of the free MaSp-NTD is pulled down for each salt condition and homolog type. Because the captured MaSp-NTD protein remains associated through two wash steps with agitation and very little MaSp-NTD protein is lost to the wash, we interpret this as an indication of stable dimer formation with resin-immobilized MaSp-NTD. The pulldown is specifically due to the MaSp-NTD dimer interaction because no free MaSp-NTD was pulled down under any conditions using resin-immobilized BSA as a control (Fig. 4). The depletion of free MaSp-NTD protein from the supernatant produced a reciprocal trend to that of the amount of protein pulled down (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Pulldown assays. Nc.MaSp1A-NTD (A), Nc.MaSp2-NTD (B), and Lm.MaSp1-NTD (C) proteins were captured from free solution through stable dimer interactions with resin-immobilized MaSp-NTD of the same type. The vertical axis is the proportion of free input protein that was captured. The key indicates the type of resin-immobilized protein and the amount of NaCl present in the binding and wash buffers for each treatment. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3).

Salt concentration also had an effect on the pulldown experiments. In higher salt conditions, it takes a lower pH before significant amounts of free MaSp-NTD are pulled down. These results are remarkably congruent with the Trp fluorescence titration and SEC results (see Figs. 2 and 3). By comparing the pulldown and Trp fluorescence results, it appears that stable dimers, as evidenced by efficient pulldown, occur only below pH values where the conformation has fully transitioned to the lower fluorescence (solvent-exposed) state. For example, at 100 mm NaCl, the Trp fluorescence completes its transition around pH 6.0 but significant pulldown does not occur until pH 5.5. Also in agreement with the Trp fluorescence data, divalent cations are more potent at disrupting pulldown than monovalent cations at equal concentrations of charges (supplemental Fig. S4B). Although 50 mm solutions of divalent cation salts do have higher ionic strength than 100 mm monovalent salts, this alone cannot explain their potency on MaSp-NTDs because they also elicit a greater effect than 200 mm NaCl (see Figs. 2 and 4). Interestingly, resin-immobilized Nc.MaSp1A-NTD was able to pull down Nc.MaSp2-NTD to about the same degree that it pulls down Nc.MaSp1A-NTD suggesting that heterodimerization may be physiologically relevant (data not shown).

To further demonstrate increased MaSp-NTD dimer stability at low pH, we performed pulldown experiments where resin with captured proteins was washed for various periods with buffer at pH of 5.5, 6.0, or 7.0 (supplemental Fig. S8). At pH 7.0 and 6.0, dimer half-life was ∼1 min (although perhaps much less at pH 7.0 given that dissociation was complete prior to the first time point tested) indicating a rapid dissociation rate due to weak dimer interaction. In contrast, at pH 5.5 dimer half-life was greater than 1.5 h, and ∼40% of the captured protein remained dimerized even after 10 h. Although some of the protein remaining after 10 h was undoubtedly due to re-dimerization after dissociation (which would slightly bias the half-life estimate to increased values), the observation that the dimerization kinetics had not yet come to equilibrium after 2 h or more of washing indicates the dimers at this pH are long lived due to a strong interaction between monomer subunits.

DISCUSSION

Dicko et al. (8) reported that the pH in the major ampullate gland changes from 7.2 in the ampulle to 6.3 in the duct. However, the lower pH measurement was taken only 0.5 mm into the 20-mm long duct and was performed on a gland surrounded by buffer at pH 7.4. Histological staining shows that H+ pump activity increases steadily along the entire length of the duct, so it is likely that the pH goes well below 6.3 (25). Interestingly, the spidroin solution in N. clavipes major ampullate glands contains a yellow pigment that is present in the final fiber. As the spidroin solution enters the duct, however, it becomes colorless. A pH titration of major ampullate contents has demonstrated that the yellow pigment does not turn clear until the solution is acidified beyond pH 5 (26), consistent with the presence of lower pH values in the duct. Direct measurement of pH along the majority of the duct will be difficult at best, if for no other reason than the minute volumes (the internal volume of the entire duct is estimated at <0.1 μl), so the pH estimate of 6.3 should represent an upper boundary of the possible pH at more distal points in the duct. Therefore, we feel that the pH range used in these studies is physiologically relevant and similar to those that MaSp proteins will encounter while traversing the duct.

It is also important to note that the salt ranges used in this study (20–200 mm) include physiologically relevant concentrations. The Na+ and K+ contents in the ampulle have been estimated at 3.1 and 0.75 mg g−1 dry weight, respectively (6). Because major ampullate gland contents are ∼66% water, this allows us to calculate that the salt concentration in the duct is about 58 mm (∼51 mm Na+ and ∼7 mm K+). The sum of Na+ and K+ remains fairly constant through the duct and into the fiber, but in the distal duct and fiber K+ predominates (5).

Our Trp fluorescence experiments demonstrate a conformational change in MaSp-NTD proteins as pH is changed from neutral to pH 5.5, and the single Trp residue becomes more solvent-exposed at lower pH. We also observe that the transition from the neutral pH conformation (conformation I) to the low pH conformation (conformation II) is sensitive to the concentration of various salts. In general, at higher salt concentrations, the transition from conformation I to II occurs at a lower pH suggesting stabilization of conformation I or destabilization of conformation II in the presence of salt.

The overall trends presented in Fig. 2, wherein the conformation of MaSp-NTDs change in response to pH and salt, are robust for several reasons. First, Nc.MaSp1A-, Nc.MaSp2-, and Lm.MaSp1-NTD proteins all produce very similar results despite having only 57–75% pairwise amino acid identity scores. Second, although the experiments presented represent titration of a single sample across pH, the same results are observed when independent samples are placed in buffers of fixed pH. Third, these independent readings at fixed pH (done only for Nc.MaSp1A-NTD) have also been performed using a variety of buffer systems, yet they always yielded similar results. Finally, when a sample is titrated from pH 7.0 to pH 5.5 and back to pH 7.0, the initial emission spectra is restored indicating the change in conformation is fully reversible.

One consideration about the biophysical forces that drive the pH-dependent conformational change of MaSp-NTDs is that Nc.MaSp1A-NTD and Lm.MaSp1-NTD have no histidines (there is one His residue present in Nc.MaSp2-NTD). This is interesting because proteins that exhibit pH-dependent changes near pH 6 often do so through a mechanism involving histidine (27). Even though Nc.MaSp2-NTD has a histidine, it seems likely that the pH-dependent conformational change occurs through a mechanism similar to that of Nc.MaSp1A-NTD and Lm.MaSp1-NTD so its histidine may play little or no role in that regard. Additionally, all three homologs lack cysteine residues, and therefore MaSp-NTD dimers are not stabilized by disulfide bonds as is believed to be the case for MaSp-CTDs (11, 20).

Ea.MaSp1-NTD also has a single nonconserved histidine at a different position that has been shown not to be critical for pH responsiveness by mutagenesis (22). Therefore, it is likely that pH sensing occurs through one or more acidic amino acid side chains (Asp or Glu) with higher than normal pKa values due to the molecular environment. A highly conserved Asp residue present in most MaSp proteins (Asp-40, see Ref. 22), which is homologous to Asp-35 in Nc.MaSp1A-NTD, does seem to be critical for the pH-dependent conformational change of Ea.MaSp1-NTD because mutation of that residue abolishes the Trp fluorescence response to pH. If the pH sensing is mediated through charge alterations on acidic residues, it is not surprising that salt affects the conformational change.

The results from the pulldown experiments clearly demonstrate that all three MaSp-NTDs under study interact as noncovalently associated dimers and that the stability and/or strength of the association is significantly enhanced at lower pH. The degree of dimer stability is indicated by the observation that the captured MaSp-NTDs remained associated with the resin-immobilized protein through multiple wash steps (10 min total time). Similarly, dimer dissociation occurs within minutes at pH 7.0 but on the order of hours at pH 5.5 (supplemental Fig. S8). Enhanced stability is also supported by the SEC experiments that show the dimers present at low salt are less stable at neutral pH than at pH 5.5. Furthermore, the observation that it requires ∼1 m NaCl for the Nc.MaSp1A-NTD to elute during SEC at a size consistent with the monomer mass further suggests that the dimer would be the predominant form at physiological salt and protein concentrations. In the crystal structure of Ea.MaSp1-NTD, a positive and a negative patch on one subunit interacts with the cognate negative and positive patches on the other subunit, respectively (22). If a similar relationship exists for Nc.MaSp1A-NTD, disruption of this ionic interaction by free ions may explain why high salt levels tend to cause dimer dissociation.

All three MaSp-NTDs examined here display conformational and self-assembly responses to physiologically relevant changes in pH. The presence of dimers and a pH-dependent conformational change has also been demonstrated for Ea.MaSp1-NTD (19, 22). Therefore, it seems very likely that whatever function Nephila and Latrodectus MaSp-NTDs have in fiber self-assembly, all other MaSp-NTDs have the same or similar function. In fact, given the high degree of conservation with the NTDs of the flagelliform and tubuliform spidroins, all spidroin NTDs probably have some functional aspects in common with MaSp-NTDs.

The nature of silk spinning presents a spider with an interesting dilemma. It requires that spidroin protein be stockpiled in the gland for extended periods of time yet be ready at a moment's notice to undergo an irreversible structural transition taking only seconds (7). At the same time, the protein must be stored in an assembly-incompetent state such that under no circumstances does the spidroin solution ever assemble into β-sheet rich aggregates prematurely, regardless of environmental temperature, the spider's nutritional status, possible body impacts from falling, etc.

The spidroin assembly process is regulated by the environmental changes that occur along the length of the duct, including a drop in pH and Na+ ion concentration and an increase in K+ and phosphate ion concentrations (5, 6, 8). There is also a slow increase in shear and elongational forces over most of the duct's length, followed by a dramatic increase in these forces near the very end of the duct (7). However, there may well be other cues that have not yet been recognized as important to fiber assembly.

Studies of recombinant partial spidroins have demonstrated that MaSp repeat domains alone can respond to shear forces and phosphate ions by forming β-sheet aggregates and that addition of a MaSp-CTD greatly enhances the amount and orderliness of the aggregation (17, 19, 20, 28). In most studies on partial spidroins having only MaSp repeats with or without a MaSp-CTD attached, the silk proteins do not respond in any way to changes in pH (17, 19, 29). The exceptions to this trend are constructs derived from Araneus ADF-3 and ADF-4 spidroins that, in fact, do respond to decreased pH (30, 31). However, these proteins are both MaSp2-like (with a high proline content), whereas nearly all other studies of recombinant proteins have focused on MaSp1-type repeats.

We propose that the conformational change in the MaSp-NTDs helps to ensure correct temporal activation of the spidroin assembly process by facilitating the interaction and alignment of the remainder of the MaSp proteins, particularly the repeat domains. Collectively, our data lead us to hypothesize that MaSp-NTDs function, at least in part, as pH sensors that undergo a conformational change in response to duct acidification, albeit one that does not significantly change the overall helical content nor protein solubility. Satisfyingly, the conditions of salt and pH that result in maximum pulldown mirror those at which the Trp fluorescence indicates full transition from conformation I to conformation II. We interpret this to indicate that the conformational change contributes directly to the stability of MaSp-NTD dimers and is likely associated with altered molecular contacts between monomer units that strengthen their interaction. It is important to note that the transition from conformation I to conformation II cannot be equated to the association of two monomers to form a dimer. This is evidenced by the lack of red shift in the Trp fluorescence of MaSp1A-NTD as protein concentration is increased (supplemental Fig. S9). Naturally, the increase in dimer stability will shift the monomer-dimer equilibrium to a higher proportion of dimers, but because MaSp-NTDs are already predominantly dimeric at neutral pH (supported by SEC and data not shown), this shift is likely to be modest.

There is an interesting implication of the stabilization of MaSp-NTD dimers as a result of the drop in pH. Because MaSp-CTDs have been shown to be stably dimerized and connected by one or more disulfide bonds (20, 28), the pH-dependent stabilization of MaSp-NTD dimers might be predicted to lead to the development of very long multimeric strands of MaSp proteins in a head-to-head and tail-to-tail arrangement (Fig. 5). Because of the high protein concentration in the duct, interactions between MaSp-NTDs of spidroins that are already joined at their respective C-terminal ends would be extremely rare. In addition, prior to the drop in pH, the weaker association of MaSp-NTDs might facilitate resolution of tangles that would also be predicted to occur as a result of random association of individual NTDs. Elongational flow forces acting upon this collection of multimeric strands could then cause the spidroins to become aligned with the direction of flow in preparation for β-sheet formation at the end of the duct (9, 10). This model describes the linear connectivity of spidroin proteins through associations at their terminal domains, not their overall spatial arrangement in the gland. Yet, it is compatible with both the liquid crystalline and micelle hypotheses of silk assembly that describe that level of organization.

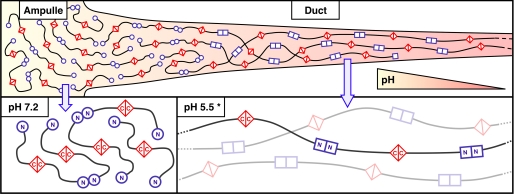

FIGURE 5.

Model of proposed MaSp assembly into multimeric strands. MaSp proteins stored in the gland ampulle (left side of top panel and bottom left panel) exist as dimers stably adjoined through their MaSp-CTDs (red triangles). The MaSp-NTDs are in conformation I at this pH (blue circles) and associate weakly with NTDs of other spidroin dimers. Through these interactions, MaSp oligomers of short lengths can be formed, and because of the dynamic nature of the NTD association, tangles of spidroins that impede flow can be resolved. As these oligomers are drawn into the duct during spinning, they eventually experience a threshold pH (middle of top panel) at which MaSp-NTDs associate much more strongly in conformation II (blue squares). Stable attachments between MaSp molecules at both termini cause the formation of long multimeric strands (bottom right panel). To emphasize the terminal domain connectivity in this schematic, the length of the repeat domains (black lines) has been greatly reduced, and the degree of entanglement or other supra-molecular organization among spidroin molecules has been simplified, and the amount of molecular alignment has been exaggerated. The proportion of MaSp-NTDs in the monomeric state at pH 7.0 has also been exaggerated for contrast purposes. Asterisk indicates the pH of the middle and distal duct has not been experimentally determined, but values at or near 5.5 are likely.

Although we do not yet have direct evidence of how the MaSp-NTD might affect fiber assembly, the pH-dependent behavior of native spidroins does support our model. When major ampullate dope from Nephila spiders is pH adjusted to 5.5, the spidroins form a gel (as would be expected for a mixture of long MaSp multimeric strands), but when brought back to pH 7.4, the solution assumes its original state (25). The pH range and reversibility of this process are consistent with our characterization of Nephila and Latrodectus MaSp-NTDs. Had the pH drop directly led to β-sheet formation, it would not have been reversible.

In a recent publication by Askarieh et al. (22), it was demonstrated that Ea.MaSp1-NTD also undergoes a pH-dependent conformational change. Consistent with the model that MaSp-NTDs facilitate spidroin assembly through this pH response, they found that recombinant E. australis MaSp1 mini-spidroins containing an NTD, four repeats, and a CTD form macroscopic assemblies at a much higher rate in acidic conditions. Silks lacking the Ea.MaSp1-NTD were pH-insensitive and assembled more slowly at low pH. However, in contrast to our own data where decreased pH stabilizes the MaSp-NTD dimer association, they found that Ea.MaSp1-NTD forms stable dimers at neutral pH that then aggregate into much larger assemblies when acidified. The MaSp-NTD homologs studied here do not exhibit this aggregation behavior (as evidenced by SEC and dynamic light scattering, supplemental Figs. S5 and Fig. S6). Whether the observed differences in dimerization dynamics and aggregation tendency are artifactual or reflective of the different species under study is as yet unclear. However, if MaSp-NTD aggregation is biologically relevant in E. australis silks, then its spidroin assembly dynamics may involve more complicated oligomeric structures than the MaSp multimeric strands we have proposed for Nephila and Latrodectus silks. Further study on mini-spidroins containing MaSp-NTDs will be needed to validate these models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Albert Abbott, and Vance Baird for helpful discussions. We also thank Drs. Kenneth Christensen, Alexey Vertegel, Robert Latour, and Dev Arya for use of their instrumentation.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant EB007403 (to W. R. M.). This work was also supported by a Sigma Xi grant-in-aid for research (to W. A. G.). This is Technical Contribution 5829 of the Clemson University Experiment Station.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) HM752779.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S9.

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- MaSp

- major ampullate spidroin

- SEC

- size exclusion chromatography

- Nc

- N. clavipes

- Lm

- L. mactans

- Ea

- E. australis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis R. V. (2006) Chem. Rev. 106, 3762–3774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X., Knight D. P., Vollrath F. (2002) Biomacromolecules 3, 644–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knight D. P., Vollrath F. (1999) Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 266, 519–523 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hijirida D. H., Do K. G., Michal C., Wong S., Zax D., Jelinski L. W. (1996) Biophys. J. 71, 3442–3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight D. P., Vollrath F. (2001) Naturwissenschaften 88, 179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X., Huang Y. F., Shao Z. Z., Huang Y., Zhou P., Knight D. P., Vollrath F. (2004) Chem. J. Chin. 25, 1160–1163 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breslauer D. N., Lee L. P., Muller S. J. (2009) Biomacromolecules 10, 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dicko C., Vollrath F., Kenney J. M. (2004) Biomacromolecules 5, 704–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight D. P., Knight M. M., Vollrath F. (2000) Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 27, 205–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefèvre T., Boudreault S., Cloutier C., Pézolet M. (2008) Biomacromolecules 9, 2399–2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sponner A., Schlott B., Vollrath F., Unger E., Grosse F., Weisshart K. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 4727–4736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu M., Lewis R. V. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 7120–7124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinman M. B., Lewis R. V. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 19320–19324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayoub N. A., Garb J. E., Tinghitella R. M., Collin M. A., Hayashi C. Y. (2007) PLoS ONE 2, e514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motriuk-Smith D., Smith A., Hayashi C. Y., Lewis R. V. (2005) Biomacromolecules 6, 3152–3159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu X., Vasanthavada K., Kohler K., McNary S., Moore A. M., Vierra C. A. (2006) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1986–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huemmerich D., Helsen C. W., Quedzuweit S., Oschmann J., Rudolph R., Scheibel T. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 13604–13612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stark M., Grip S., Rising A., Hedhammar M., Engström W., Hjälm G., Johansson J. (2007) Biomacromolecules 8, 1695–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedhammar M., Rising A., Grip S., Martinez A. S., Nordling K., Casals C., Stark M., Johansson J. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 3407–3417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagn F., Eisoldt L., Hardy J. G., Vendrely C., Coles M., Scheibel T., Kessler H. (2010) Nature 465, 239–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rising A., Hjälm G., Engström W., Johansson J. (2006) Biomacromolecules 7, 3120–3124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Askarieh G., Hedhammar M., Nordling K., Saenz A., Casals C., Rising A., Johansson J., Knight S. D. (2010) Nature 465, 236–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaines W. A., 4th., Marcotte W. R., Jr. (2008) Insect Mol. Biol. 17, 465–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayoub N. A., Hayashi C. Y. (2008) Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vollrath F., Knight D. P., Hu X. W. (1998) Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 265, 817–820 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dicko C., Kenney J. M., Knight D., Vollrath F. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 14080–14087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foo C. W., Bini E., Hensman J., Knight D. P., Lewis R. V., Kaplan D. L. (2006) Applied Physics a-Materials Science & Processing 82, 223–233 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisoldt L., Hardy J. G., Heim M., Scheibel T. R. (2010) J. Struct. Biol. 170, 413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fahnestock S. R., Irwin S. L. (1997) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47, 23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rammensee S., Slotta U., Scheibel T., Bausch A. R. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6590–6595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slotta U. K., Rammensee S., Gorb S., Scheibel T. (2008) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 4592–4594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.