Abstract

Influenza virus transcription is a prototype of primer-dependent initiation. Its replication mechanism is thought to be primer-independent. The internal initiation and realignment model for influenza virus genome replication has been recently proposed (Deng, T., Vreede, F. T., and Brownlee, G. G. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 2337–2348). We obtained new results, which led us to propose a novel model for the initiation of viral RNA (vRNA) replication. In our study, we analyzed the initiation mechanisms of influenza virus vRNA and complementary RNA (cRNA) synthesis in vitro, using purified RNA polymerase (RdRp) and 84-nt model RNA templates. We found that, for vRNA → cRNA →, RdRp initiated replication from the second nucleotide of the 3′-end. Therefore, host RNA-specific ribonucleotidyltransferases are required to add one nucleotide (purine residues are preferred) to the 3′-end of vRNA to make the complete copy of vRNA. This hypothesis was experimentally proven using poly(A) polymerase. For cRNA → vRNA, the dinucleotide primer AG was synthesized from UC (fourth and fifth from the 3′-end) by RdRp pausing at the sixth U of UUU and realigning at the 3′-end of cRNA template; then RdRp was able to read through the entire template RNA. The RdRp initiation complex was not stable until it had read through the UUU of cRNA and the UUUU of vRNA at their respective 3′-ends. This was because primers overlapping with the first U of the clusters did not initiate transcription efficiently, and the initiation product of v84+G (the v84 template with an extra G at its 3′-end), AGC, realigned to the 3′-end.

Keywords: RNA, RNA Polymerase, RNA Viruses, Viral Polymerase, Viral Replication, Viral Transcription, Virus

Introduction

Most RNA viruses use their own RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp)2 to transcribe and replicate their genome (1). The initiation mechanisms of RdRp can be classified into primer-dependent and -independent (de novo) initiation types (2, 3).

Influenza virus transcription is considered a prototype of primer-dependent transcription. It uses the host mRNA derived cap-1 structure as a primer. The virus RdRp binds to the cap-1 structure of the host mRNA and cleaves 10–13 nucleotides, usually after purine residues, in order to generate a primer for transcription (4, 5). The purified influenza virus ribonucleoprotein complex from virion uses dinucleotide AG and mRNA as primers and does not transcribe in the absence of primers. The RdRp heterotrimer purified from an influenza virion consists of three subunits, PB1, PB2, and PA (6). The purified influenza virus RdRp from insect and mammalian cells catalyzes AG and cap-1 primed transcription and polyadenylation (model of viral transcription) and de novo initiation (model of viral genome replication) in vitro (7–9).

To date, no specific structure has been identified at the 5′ termini of influenza virus genomes, and de novo initiation was proposed as the replication mechanism. De novo initiation is believed to start at the first residue of the 3′-terminus of the template and is immediately followed by elongation. However, in some cases, short RNA oligonucleotides are transcribed by abortive de novo transcription from either the 3′-terminal nucleotides or internal nucleotides, including cis-acting RNA-replicating elements of the template (cre) (10, 11). These oligonucleotides are subsequently used as primers for elongation, as reported for the so-called prime-and-realign or jumping back mechanism (10, 12).

The “corkscrew” structure of the 5′- and 3′-ends of influenza virus vRNA and cRNA has been accepted after various mutation studies of intra- and interstrand complementarity and disparity (13–18). During influenza virus infection, vRNA is first replicated into cRNA, and then the cRNA is replicated into vRNA (19–21). Recently, Brownlee and co-workers (22) proposed the internal initiation and prime-and-realign model for replication. In this model, the dinucleotide primer AG is synthesized from the internal UC sequence of the 3′-end of the cRNA and then realigned to the 3′-ends of both v- and cRNA, in order to start replication. This is similar to the mechanism used by Tacaribe virus (12).

In this study, we analyzed the initiation mechanism of influenza virus RdRp in vitro in detail and found that both vRNA → cRNA and cRNA → vRNA replication were initiated from internal sequences of templates. We propose a new initiation mechanism model for the replication of vRNA.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression, Purification, and in Vitro Transcription of the Influenza Virus RdRp Heterotrimer

The expression, purification, and in vitro transcription of influenza virus RdRp heterotrimer were performed as previously reported (9).

Abortive Transcription Assay

Abortive transcription was performed in 50 μm [γ-32P]ATP and 0.5 mm GTP or in 50 μm [γ-32P]GTP and 0.5 mm CTP. The dinucleotide products were applied to 25% PAGE with 4 m urea before being subjected to image analysis with Typhoon Trio Plus (GE Healthcare).

Kination Labeling of Oligonucleotides

The synthesized oligonucleotides were labeled with 0.5 mm [γ-32P]ATP using T4 nucleotide kinase.

Model RNA Templates

RNA templates V-wt (23) (referred to as v53 throughout), v84, c84, and their mutant RNA templates were prepared via in vitro transcription using the MegaShort Script kit (Ambion), as reported previously (24). Templates v83, v84+A, v84+C, v85+G, v84+U, c84(U4A), c84(14A,U4A), c84(U6A), c84(U7A), c84(U8A), and c83 were made using the QuikChangeII site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Their sequences were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing (Invitrogen). The primer sequences are available upon request.

In Vitro Replication with Poly(A) Polymerase

Two hundred nm v84 was incubated with 2 units/ml poly(A) polymerase in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 8 mm MgCl2, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm DTT, 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, and GTP, and 0.05 mm [α-32P]UTP at 25 °C for 5 min. After poly(A) polymerase was inactivated by boiling for 1 min, 100 nm influenza RdRp and 2000 units/ml RNase inhibitor were added, and the reaction was continued at 25 °C for 2 h.

Chemicals and Radioisotopes

All oligonucleotides were synthesized by Takara, and the enzymes were purchased from the same source. The nucleotides were from GE Healthcare, and [α-32P]UTP, [α-32P]CTP, [γ-32P]GTP, and [γ-32P]ATP were from PerkinElmer Life Sciences.

RESULTS

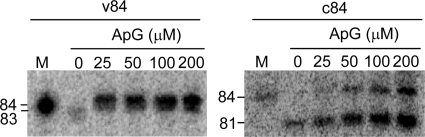

Primer Concentration Dependence of v84 and c84

It has been previously reported that influenza RdRp primes from the dinucleotide primer, AG (22, 24). In our study, using AG primer resulted in 81- and 84-nt products from c84 RNA template in 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or GTP and 50 μm [α-32P]UTP in a concentration-dependent manner. Fifty μm AG was sufficient to produce an 84-nt-long oligonucleotide from c84 RNA. v84 template produced an 84-nt sequence in the presence of 25 μm AG, and the amount of the product plateaued at 0.1 mm AG (Fig. 1) (9). De novo initiation products of v84 and c84 RNA templates were 83 and 81 nt long, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

The effect of the concentration of the dinucleotide AG primer. v84 and c84 templates were transcribed using various concentrations of the dinucleotide primer AG. The concentration (μm) of AG primer is indicated above the PAGE. The sizes of the RNA products are shown on the left. M, v84 and c84 transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase.

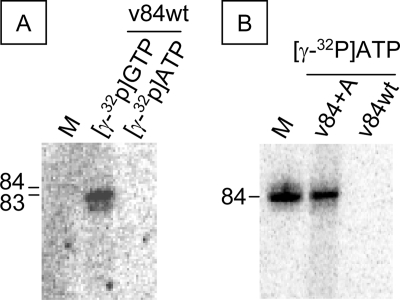

The Effects of the 3′ Sequences of the vRNA Templates and Primers

The initiation position of v84 template was analyzed using 0.1 mm primers AG, AA, CC, CA, GC, GG, GU, UU, AGC, AGCA, and dAdG in 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or GTP and 50 μm [α-32P]UTP (Fig. 2A). AG and AGC produced an 84-nt-long transcript, indicating that they primed from the 3′-end of v84. Using GC resulted in an 83-nt-long product, suggesting that it primed from the second C from the 3′-end. An 84-nt product was also made in the presence of GG, indicating that it primed from the 3′-end. We found that AGC was as effective as AG, whereas dAdG did not prime transcription of v84 template. CC, UU, and GU, which were complementary to the internal sequences of v84, did not show priming activity. AA and CA, partially complementary to U (−4), produced 85-nt transcripts. Using AGCA resulted in an 87-nt product (see arrowhead in Fig. 2A), indicating that they primed not only from the complementary 3′-ends but also from another position where their 3′-terminal A annealed to the 3′-end U of v84. The primers complementary to the 3′-UCG of v84 template (AG, GC, GG, and AGC) showed strong priming activity. However, those complementary to the sequences of the 5′ of U(−4) (AA, CC, GU, UU, CA, and AGCA) showed weak or no activity. Weak signals from 83-nt products were always detected and were attributed to a de novo initiation product on v84 template (9).

FIGURE 2.

In vitro transcription of v84 mutant templates. The model RNA templates, v84wt (A), v84+A (B), v84+G (C), v84+U (D), v84+ C (E), and v53 (F), were transcribed in vitro. The sequences of the templates (boldface type) and primers are shown above the PAGE. The sizes of the RNA products are shown on the left and on the right of the PAGE. The 85- and 87-nt products are indicated by arrowheads (A).

Because the length of the de novo initiation product of v84 was 83 nt, we tested the priming of the 85-nt-long vRNA templates with an additional nucleotide at the 3′-end of v84. The 84-nt-long de novo initiation products were observed for v84+A (Fig. 2B) and v84+G (Fig. 2C) templates, and the weak 84-nt product signals were also found for v84+U template (Fig. 2D). No clear 84-nt product signals were observed for v84+C (Fig. 2E) template. AG produced the 84-nt-long sequences from all templates, and the 85-nt products were found when using the dinucleotide primers designed for the additional sequences. However, in addition to the 84-nt product, an 87-nt product was made when priming v84+G template with AG. This is difficult to interpret; one explanation is that the oligonucleotide AGC was synthesized and relocated from U(−5) to the 3′-end, thereby allowing C to anneal to the G at the 3′-end (Fig. 2C). C was added because it is the complementary nucleotide to G at the fourth position from the 3′-end. One-nucleotide shorter products were also made from another vRNA model template, v53, without primers (Fig. 2F).

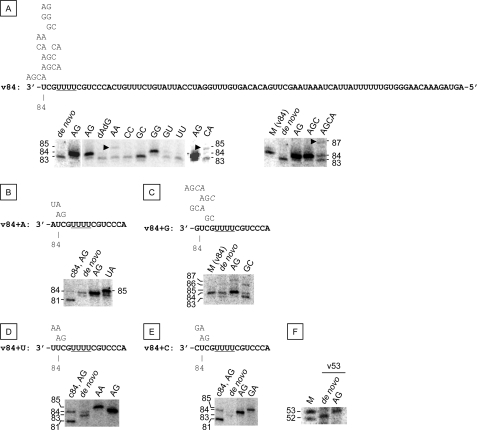

De Novo Initiation via the Internal Initiation of Templates

We found that the replication initiation site of the vRNA was located at the second nucleotide of the 3′-end, which disagrees with the previous reports (7, 22). Therefore, we examined first the initiation nucleotide of v84 using [γ-32P]ATP and [γ-32P]GTP and that of v84+A with [γ-32P]ATP.

Using 50 μm [γ-32P]GTP and 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or UTP, an 83-nt sequence was obtained by de novo initiation of v84 template. The size of this product was identical to the initiation product observed under standard de novo initiation conditions (Fig. 3A). No products were found using 50 μm [γ-32P]ATP and 0.5 mm GTP, CTP, or UTP. An 84-nt product was made with v84+A template in 200 μm [γ-32P]ATP and 0.5 mm GTP, CTP, or UTP (Fig. 3B). These data strongly suggest that de novo initiation starts at the second position of the 3′-end of vRNA templates.

FIGURE 3.

De novo initiation of v84wt and v84+A. A, v84wt was incubated without primers in 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or UTP and 50 μm [γ-32P]GTP ([γ-32P]GTP), and in 0.5 mm of GTP, CTP, or UTP and 0.2 mm [γ-32P]ATP ([γ-32P]ATP). B, v84+A and v84wt were incubated without primers in 0.5 mm GTP, CTP, or UTP and 0.2 mm [γ-32P]ATP. The sizes of the RNA products are marked on the left. M, [32P]v84 transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase.

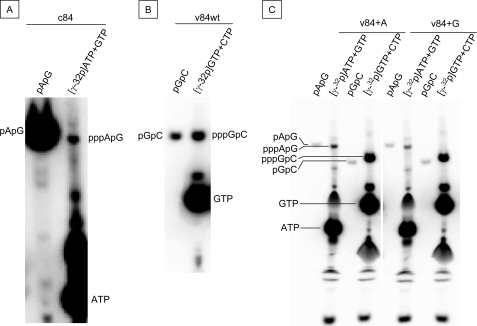

Next, we examined dinucleotide synthesis using 50 μm [γ-32P]ATP and 1 mm GTP for c84 template or 50 μm [γ-32P]GTP and 1 mm CTP for v84. pppApG was produced from c84 (Fig. 4A), pppGpC was from v84 (Fig. 4B), and pppApG and pppGpC were obtained from v84+A and v84+G templates, respectively (Fig. 4C). The results of GC synthesis using v84 template and those for AG synthesis from v84+A and v84+G agree with the proposed initiation at the second position from the 3′-end of vRNA templates.

FIGURE 4.

Dinucleotide synthesis in vitro. A, c84 template was incubated without primers in 0.5 mm GTP and [γ-32P]ATP. B, v84wt was incubated without primers in 0.5 mm ATP and [γ-32P]GTP. C, v84+A and v84+G were incubated without primers in 0.5 mm GTP and [γ-32P]ATP and in 0.5 mm of ATP and [γ-32P]GTP. The RNA products were separated on 25% PAGE containing 6 m urea. The synthesized oligonucleotides, AG (pApG) and GC (pGpC), were used as markers after being labeled by kination with [γ-32P]ATP.

Influenza in Vitro Replication with Poly(A) Polymerase

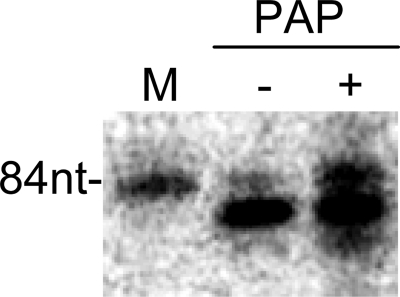

In order to test the possibility of the nucleotide addition to the 3′-end of v84 by host RNA-specific ribonucleotidyltransferases, poly(A) polymerase was used under in vitro influenza replication conditions (Fig. 5). The 84-nt-long replication products were obtained using this procedure.

FIGURE 5.

Influenza in vitro replication with poly(A) polymerase. In vitro replication of v84 without primer were performed with (+) or without (−) pretreatment with 2 units/ml poly(A) polymerase (PAP). M, [32P]v84. The position of 84-nt RNA is indicated on the left.

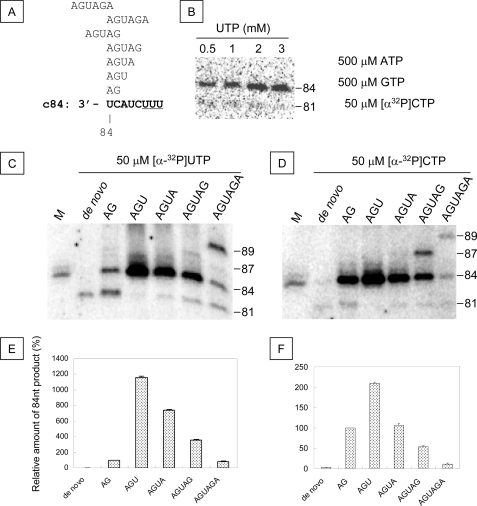

Nucleotide Concentration and Primer-dependent Initiation of c84

Because our results supported the hypothesis of AG synthesis from the fourth U at the 3′-end of cRNA templates (Fig. 4A) (22), we examined the mechanism of the translocation of the AG synthesized from U(−4)C, when the 84-nt products were transcribed.

First, in order to analyze the mechanism of the production of 84- and 81-nt sequences from c84 RNA template, we tested the effects of various primers and concentrations of UTP (to be incorporated at the third position of the priming strand (Fig. 6)). When 50 μm UTP was used, both the 81- and 84-nt sequences were produced with AG primer, and only the 81-nt sequence was observed in the absence of primers (Fig. 6C). At 50 μm UTP, the 84-nt products were made using AGU, AGUA, and AGUAG. The primer activity of AGU was the highest, and those of AGUA, AGUAG, and AG were lower, decreasing in that order. Using AGU resulted in the 84-nt product only. When the concentration of UTP was higher than 0.5 mm, the 84-nt products were made, both in the presence of AG and with longer primers (Fig. 6, B and D). A UTP concentration higher than 0.5 mm was required for efficient read-through from the 3′-end of c84 template to obtain the 84-nt products.

FIGURE 6.

In vitro transcription of the c84 template. A, the initiation positions of the primers are aligned to the sequence of the 3′-end of c84 template (boldface type). The U cluster is underlined. B, the effect of UTP concentration on AG-primed transcription of c84. The nucleotide concentrations are shown on the right, and the concentration of UTP is shown above the PAGE. C and E, in vitro transcription of c84 with or without 0.1 mm primers. c84 (200 nm) was incubated in 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or GTP and 50 mm [α-32P]UTP (C), and the amount of the 84-nt product relative to that of the AG primer was calculated (E). D and E, in vitro transcription of c84 with or without 0.1 mm primers. c84 (200 nm) was incubated in 0.5 mm ATP, GTP, or UTP and 50 mm [α-32P]CTP (D), and the amount of the 84-nt product relative to that of the AG primer was calculated (F). The mean and S.D. (error bars) of the relative amount of the 84-nt product were calculated from three independent experiments (E and F). The sequence of the primer is shown above the PAGE (C and D) and below the graph (E and F).

Primer activity of AGU was the highest, and those of AGUA, AG, and AGUAG were lower, decreasing in that order, at both 50 and 500 μm UTP. Using AGUAGA primer at those UTP concentrations, more 89-nt product than 84-nt product was made. An 87-nt product was also found. The 81-nt sequences were produced de novo and in the presence of the AG, AGUA, AGUAG, and AGUAGA primers. The trinucleotide primer AGU had the strongest activity. When using other primers, 81-nt products were also observed, starting at −4U.

The 87-nt sequences from AGUAG can be attributed to initiation from the AG sequence of the primer (Fig. 6A). The 89-nt products obtained using AGUAGA might have been produced by 3′-A of the primer annealing to the 3′-end of the template (Fig. 6A).

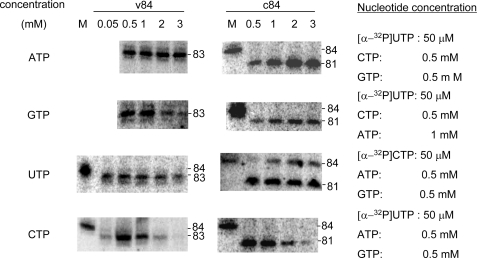

Nucleotide Concentration and de Novo Initiation

Second, the effect of nucleotide concentration on de novo initiation from v84 and c84 templates was investigated, because the UTP concentration affected the position of the AG-primed initiation from c84 template (Fig. 6).

UTP concentration above 1 mm was required for efficient de novo initiation of the 84-nt sequence from c84 template in 50 μm CTP (Fig. 7). In 50 μm UTP, only the 81-nt products were observed. CTP concentration higher than 2 mm inhibited de novo initiation of c84, whereas the GTP concentration did not affect it.

FIGURE 7.

The effect of nucleotide concentration on de novo initiation. The substrate composition is shown on the right. The concentration of the substrate shown on the left is indicated above. The sizes of the RNA products are shown on the right. M, [32P]v84 transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase.

No 84-nt de novo initiation products were obtained with v84 template at any of the nucleotide concentrations used, but some 83-nt-long products were observed. Incubation in 0.5 mm CTP produced the greatest amount of the 83-nt sequences. GTP, UTP, and CTP concentrations above 2 mm inhibited de novo initiation on v84 template. However, even 3 mm ATP did not inhibit de novo initiation of v84 or c84 template-based synthesis.

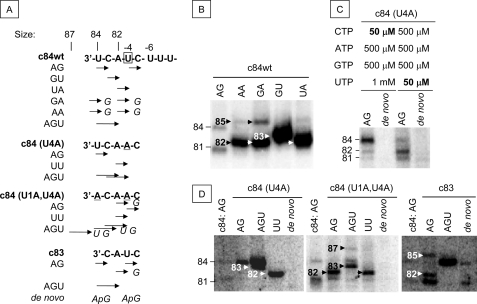

The Effects of the 3′ Sequences of cRNA Template and Primers

Third, we tested the initiation of c84 (c84wt) transcription primed by AG, GU, UA, GA, and AA in 50 μm [α-32P]UTP and 0.5 mm ATP, GTP, or CTP. Using AG under these conditions, similar amounts of the 84- and 81-nt products were obtained (Fig. 8B). The expected length RNAs were produced by priming with GU, UA, and AGU. However, a small amount of an 85-nt product was observed in the presence of AA and GA, which could be attributed to initiation from the 3′-U of c84wt.

FIGURE 8.

Mapping of the primer-dependent initiation sites of c84 and its mutants. A, the 3′-end sequences of c84wt, c84(U4A), c84(U1A,U4A), and c83 are indicated in boldface type, and the initiation sites of the di- and trinucleotide primers are indicated by arrows. U at the fourth position (−4) from the 3′-end is surrounded by a square. The mutated sequences are underlined. The added G and de novo synthesized ApG are shown in italic type. B, c84wt was incubated with a 0.1 mm concentration of the dinucleotide primer AG, AA, GA, GU, or UA in 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or GTP and 50 mm [α-32P]UTP. C, c84(U4A) was incubated without (de novo) or with 0.1 mm AG in 0.5 mm ATP, GTP, or UTP and 50 mm [α-32P]CTP or in 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or GTP and 50 mm [α-32P]UTP. D, c84(U4A), c84(U1A,U4A), and c83 were incubated without (de novo) or with a 0.1 mm concentration of the primer AG, AGU, or UU in 0.5 mm ATP, GTP, or UTP and 50 mm [α-32P]CTP. c84wt transcribed with AG in 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or GTP and 50 mm [α-32P]UTP was used as the size marker (c84: AG). The sizes of the RNA products are indicated on the left of the PAGE. Products are marked with their sizes in the PAGE.

When the U at the fourth position (−4) from the 3′-end was changed to A (c84(U4A)), AG-primed products with different lengths were observed in a UTP concentration-dependent manner, whereas no products were found in the absence of primers (Fig. 8C). Using AG at 1 mm UTP, the 84-nt products were made, and the 82-nt products were obtained at 50 μm UTP. UTP was incorporated at the third nucleotide of the c84-derived templates and affected the elongation of RNA during both the primer-dependent and -independent initiation with this template (Fig. 7).

In order to determine the initiation positions of c84(U4A) and c84(U1A,U4A) templates, in which the first and both the first and fourth U from the 3′-end, respectively, were mutated to A, and the initiation position of c83 template, which was missing its 3′-U, they were incubated with 50 μm [α-32P]CTP, 0.5 mm ATP and GTP, and 1 mm UTP. No products were obtained from these templates in the absence of primers. These data support the idea of primer synthesis from U(−4)C(−5) (22).

The products were aligned to their template sequences (Fig. 8A). However, some products of unexpected size were observed. These were an AGU-primed 83-nt product obtained using c84(U4A) template and an AG-primed 87-nt product, an AGU-primed 83-nt product, and a UU-primed 82-nt product made with c84(U1A,U4A) RNA. An AG-primed 85-nt product and a de novo initiated 84-nt product of c83 template were also found (Fig. 8D). These unexpected products may have been made by halting RNA elongation at the fifth position from the 3′-end (C at −5) and relocation of the aborted products to the 3′-end to allow the templates to be read-through. GA and AA annealed at A(−3)U(−4) of c84wt template and produced 82-nt sequences. Some of the primers were relocated to the U(−1)C(−2) after the addition of G (GAG and AAG), by annealing of the GAG and AAG (underlined is the AG sequence of the elongated primers) with the 3′-U(−1)C(−2) of c84wt. Under those conditions, the 85-nt products were observed.

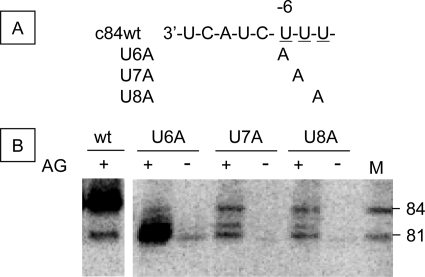

Finally, to test the possibility of primer release at UUU sites of c84 (nucleotides 6–8 from the 3′-end), each U was changed to A (Fig. 9) (22). The UTP concentration above 1 mm was required for read-through from the 3′-end of c84 template (Fig. 7). c84(U6A), c84(U7A), and c84(U8A) templates were incubated with 0.5 mm ATP and GTP, 1 mm UTP, and 50 μm [α-32P]CTP with or without 0.1 mm AG primer. In the absence of AG, only 81-nt products were observed (Fig. 7). When AG was added, a large amount of the 84-nt product and a small amount of the 81-nt product were made from c84wt template (Fig. 9). Using c84(U6A) template, a large amount of the products with 81-nt length and a small amount of the 84-nt product were observed in the presence of AG primer, and only the 81-nt products were found in its absence. For c84(U7A) and c84(U8A) templates, the 84- and 81-nt products and a small amount of the 82-nt product were observed in the presence of AG. In the absence of primers, only a faint band relating to the 81-nt product was apparent. These products are different from those obtained by Deng et al. (22) using a two-template system. However, in their paper, short sequences were produced in the presence of AG from a 6U→A mutant template, which was similar to our mutants.

FIGURE 9.

Effect of the UUU (−6 to −8) sequence of the 3′-terminus of c84 template. A, the 3′-end sequences of c84wt (wt) and the U stretch mutants (U6A, U7A, and U8A). B, RNA products of c84wt and the mutant (U6A, U7A, and U8A) templates. cRNA templates were transcribed with (+) or without (−) 0.1 mm AG primer in 0.5 mm ATP or GTP or 1 mm UTP and 50 μm [α-32P]CTP. c84wt transcribed with AG in 0.5 mm ATP, CTP, or GTP and 50 mm [α-32P]UTP was used as the size marker (M). The sizes of the RNA products are shown on the right.

DISCUSSION

The transcription of the influenza virus involves the use of cap-1 containing host mRNA as a primer (25, 26) and the dinucleotide primer AG, which is complementary to the 3′-end of the genome. GG and AGC primers have been used before for in vitro transcription with influenza RdRp (27–29). The replication of the influenza virus is believed to be initiated without primers because the RNA genome (vRNA) purified from the virus was found to possess a terminal triphosphate at the 5′-end (30). The purified RdRp heterotrimer was found to initiate transcription from the 3′-end of vRNA without primers (7, 22). Recently, the internal initiation and primer realignment model of influenza virus replication was proposed by Brownlee and co-workers (22). However, our influenza virus RdRp initiated replication from internal sequences of v84 (9), v53, and c84 templates without primers (Figs. 1, 2, and 6–8).

First, we determined the mechanism of vRNA → cRNA replication initiation. In our system, the de novo initiation product of v84 template was 83 nt in length, starting from the GTP at the second nucleotide (Figs. 2 and 3A). When an additional nucleotide was added to the 3′-end of v84 template, an 84-nt long sequence was produced, the transcription of which was initiated from the A at the second nucleotide of the 3′-end of the template (Figs. 2 and 3B). Purine residues were effective, but C was not effective for de novo initiation from this position.

We obtained the 52-nt products using v53 template without primers (Fig. 2F). This was the model RNA template identical to that used by Honda et al. (7). Deng et al. (22) used a two-RNA system. In contrast, we used a single RNA, which acts as the replicon genome when GFP and CAT sequences are inserted into the HindIII site (31, 32). Therefore, our in vitro system reflects more closely the influenza genome replication in infected cells.

The major difference between our system and that of Deng et al. (22) and Honda et al. (7) is the use of highly purified RdRp. In the study of Deng et al. (22) study, the purity of RdRp prepared using the TAP method was less than 25% (33), and the RdRp of Honda et al. (7) might have contained other proteins. We make that assumption because washing with 5 mm imidazole might not be completely effective in removing the proteins without the His tag bound to metal affinity resins (34). It is also possible that contaminating factors in their preparations could have helped the initiation from the 3′-end. This seems to be likely if we consider the large number of RNA-specific ribonucleotidyltransferases that add ribonucleotides to the 3′-ends of RNA, known to be present in the cell (35).

In order to confirm the possibility of nucleotide addition to the 3′-end of vRNA by host RNA-specific ribonucleotidyltransferases, we used poly(A) polymerase, the commercially available enzyme of that transferase family, and demonstrated the synthesis of the full-length copy of vRNA template in vitro (Fig. 5). This assumption seemed to be reasonable because nucleotide addition has been previously observed in a minireplicon system (22).

Next, we determined the mechanism of primer relocation on cRNA. Influenza RdRp was sensitive to UTP concentration, which was incorporated at the 14th nucleotide from the 3′-end of the v84 template and the third nucleotide from the 3′-end of c84 (Figs. 2 and 7). The concentrations of the nucleotides incorporated at the beginning of transcription affected the elongation of the products (36). In particular, 50 μm UTP limited the formation of the stable initiation complex from the 3′-end of c84 (Figs. 6 and 7), which was similar to the abortive initiation of T7 and Escherichia coli RNA polymerases (37, 38). This UTP sensitivity is consistent with high primer activity of AGU in the case of c84 (Fig. 6). While using a low UTP concentration (50 μm), 50 μm AG was required for the priming from the 3′-end of c84 template, although 25 μm AG was enough for the priming at U(−4)C(−5) of c84 and from the 3′-end of v84 (Figs. 1 and 6).

AGCA did not prime v84 template, and AGUAGA did not prime c84 efficiently. An A residue is present at the 3′-ends of both primers. This anneals to the first U of the U clusters at the 3′-ends of templates, although the primer length differs between v84 and c84 (Figs. 2A and 6). Both U clusters are located in the loop domain of the corkscrew structure, and the first U from the 3′-end does not undergo base pairing (33). However, the poor priming effect of these primers did not arise from the weak annealing of A-U sequences or the length of the primer because AGUA primed efficiently from c84. Furthermore, the initiation complex of the AGC that elongated from AG was not stable at the UUUU of v84+G, and AGC realigned to the 3′-end of v84 (Fig. 2D; C was added to the AG primer). RdRp may pause or slip at U clusters containing more than three Us, in a manner similar to polyadenylation at the U stretch of the 5′-end of vRNA (39, 40). This causes the paused initiation complex to be released from the template and then realign to the 3′-end of vRNA. This is similar to the mechanism of abortive transcription, where the paused RdRp aborts the initiation (37).

This led us to the elucidation of the mechanism of the primer realignment of cRNA. The replication initiation from cRNA started from U(−4)C(−5) (Fig. 4B) (22) and the dinucleotide primer AG, which was synthesized from the UC sequence. It was released from the template because the initiation complex paused at the first U(−6) of UUU (−6 to −8). When U(−6) was changed to A, the RdRp-AG primer complex read through efficiently from U(−4)C(−5) and produced an 81-nt sequence (Fig. 9). The RNA product made from the 3′-end by AG realignment was 5 nt in length, which was stable enough to allow RdRp to read through the UUU and produce the 84-nt RNA.

The translocation of AG from cRNA to vRNA is possible in influenza-replicating cells, and the synthesized AG enhances cRNA → vRNA in infected cells (22). This might produce more vRNA because vRNA transcription is initiated by a lower concentration of AG than cRNA transcription (Fig. 1). However, during the initial infection, cRNA does not exist in the infected cell until the first step of genome replication (vRNA → cRNA), which is initiated in the absence of a primer, takes place. In our in vitro system, the influenza RdRp-vRNA transcription complex was resistant to heparin treatment (9), which indicated that RdRp remained bound to the vRNA template during transcription and did not move to the newly synthesized cRNA. Therefore, we come to the conclusion that RdRp replicates vRNA in the absence of primers.

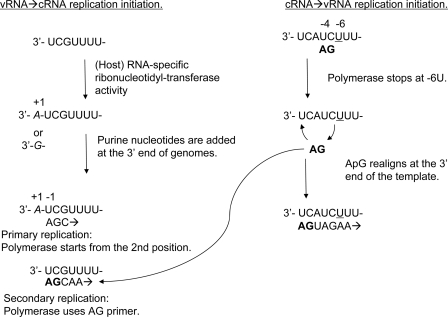

To summarize, in the influenza RdRp system, replication occurs via primer-independent (de novo) RNA synthesis. We propose that both de novo initiation (replication) of influenza virus vRNA and cRNA start from internal sequences (Fig. 10). The second nucleotide from the 3′-end of vRNA and the fourth and fifth UC of cRNA are the proposed initiation sites. However, the initiated RNA synthesis may not be stable until RdRp passes through the U clusters in the 3′-ends of vRNA and cRNA, which induces the primer realignment of cRNA.

FIGURE 10.

Our model of influenza genome replication initiation. vRNA → cRNA replication initiation is shown as follows. First, an additional nucleotide (in italic type) is added to the 3′-end of vRNA by the RNA-specific ribonucleotidyltransferase of the host. Influenza RdRp initiates replication from the U at −2 and reads through to the UUUU (primary replication). The dinucleotide AG produced from the resultant cRNA can then be used for replication initiation (secondary replication). cRNA → vRNA replication initiation is shown as follows. The replication initiation from cRNA starts from U(−4)C(−5) (22). The dinucleotide AG (in boldface type), which is synthesized from U(−4)C(−5), is released from the template because RdRp becomes stuck at the underlined U (−6) of UUU (−6 to −8), as in polyadenylation at the U stretch of the 5′-end of vRNA (40), and is then relocated to the 3′-end of cRNA to allow it to read through the UUU.

This work was supported Chinese Academy of Sciences Grant 0514P51131, National Science Foundation of China Grant 30670090, Li Ka Shing Foundation Grant 0682P11131, RESPARI Grant 0581P14131, and FLUINNATE Grant SP5B-CT-2006-044161.

- RdRp

- RNA-dependent RNA polymerase(s)

- vRNA

- viral RNA

- cRNA

- complementary RNA

- nt

- nucleotide(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball L. A. (2007) in Fields Virology (Knipe D. M., Howley P. M. eds) 5th Ed., pp. 119–140, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Dijk A. A., Makeyev E. V., Bamford D. H. (2004) J. Gen. Virol. 85, 1077–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kao C. C., Singh P., Ecker D. J. (2001) Virology 287, 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plotch S. J., Bouloy M., Ulmanen I., Krug R. M. (1981) Cell 23, 847–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaton A. R., Krug R. M. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 6282–6286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honda A., Mukaigawa J., Yokoiyama A., Kato A., Ueda S., Nagata K., Krystal M., Nayak D. P., Ishihama A. (1990) J. Biochem. 107, 624–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honda A., Mizumoto K., Ishihama A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 13166–13171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newcomb L. L., Kuo R. L., Ye Q., Jiang Y., Tao Y. J., Krug R. M. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 29–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S., Weng L., Geng L., Wang J., Zhou J., Deubel V., Buchy P., Toyoda T. (2010) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 570–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul A. V., Rieder E., Kim D. W., van Boom J. H., Wimmer E. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 10359–10370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y., Rijnbrand R., Watowich S., Lemon S. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12659–12667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcin D., Kolakofsky D. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 1370–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flick R., Hobom G. (1999) J. Gen. Virol. 80, 2565–2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baudin F., Bach C., Cusack S., Ruigrok R. W. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 3158–3165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fodor E., Pritlove D. C., Brownlee G. G. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 4092–4096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann G., Hobom G. (1995) J. Gen. Virol. 76, 1709–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pritlove D. C., Poon L. L., Devenish L. J., Leahy M. B., Brownlee G. G. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 2109–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poon L. L., Pritlove D. C., Sharps J., Brownlee G. G. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 8214–8219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishihama A., Nagata K. (1988) CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 23, 27–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamb R. A., Choppin P. W. (1983) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 52, 467–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krug R. M. (1983) in Genetics of Influenza Viruses (Palese P., Kingsburry D. W. eds) pp. 70–98, Springer-Verlag, New York [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng T., Vreede F. T., Brownlee G. G. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 2337–2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parvin J. D., Palese P., Honda A., Ishihama A., Krystal M. (1989) J. Virol. 63, 5142–5152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi M., Toyoda T., Ishihama A. (1996) Arch. Virol. 141, 525–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaton A. R., Krug R. M. (1981) Nucleic Acids Res. 9, 4423–4436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palese P., Shaw M. L. (2007) in Fields Virology (Knipe D. M., Howley P. M. eds) 5th Ed., pp. 1647–1689, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawakami K., Ishihama A., Hamaguchi M. (1981) J. Biochem. 89, 1751–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plotch S. J., Krug R. M. (1977) J. Virol. 21, 24–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plotch S. J., Krug R. M. (1978) J. Virol. 25, 579–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honda A., Mizumoto K., Ishihama A. (1998) Virus Res. 55, 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toyoda T., Hara K., Imamura Y. (2003) Arch. Virol. 148, 1687–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamanaka K., Ogasawara N., Yoshikawa H., Ishihama A., Nagata K. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 5369–5373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng T., Sharps J. L., Brownlee G. G. (2006) J. Gen. Virol. 87, 3373–3377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honda A., Endo A., Mizumoto K., Ishihama A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31179–31185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin G., Keller W. (2007) RNA 13, 1834–1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ling M. L., Risman S. S., Klement J. F., McGraw N., McAllister W. T. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 1605–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu L. M., Vo N. V., Kane C. M., Chamberlin M. J. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 3777–3786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moroney S. E., Piccirilli J. A. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 10343–10349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson H. D., Dickson E., Plotch S. J., Krug R. M. (1980) Nucleic Acids Res. 8, 925–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo G. X., Luytjes W., Enami M., Palese P. (1991) J. Virol. 65, 2861–2867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]