Abstract

Substrates of the N-end rule pathway are recognized by the Ubr1 E3 ubiquitin ligase through their destabilizing N-terminal residues. Our previous work showed that the Ubr1 E3 and the Ufd4 E3 co-target an internal degron of the Mgt1 DNA repair protein. Ufd4 is an E3 of the ubiquitin-fusion degradation (UFD) pathway that recognizes an N-terminal ubiquitin moiety. Here we report that the RING-type Ubr1 E3 and the HECT-type Ufd4 E3 interact, both physically and functionally. Although Ubr1 can recognize and polyubiquitylate an N-end rule substrate in the absence of Ufd4, the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex is more processive in that it produces a longer substrate-linked polyubiquitin chain. Conversely, Ubr1 can function as a polyubiquitylation-enhancing component of the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex in its targeting of UFD substrates. We also found that Ubr1 can recognize the N-terminal ubiquitin moiety. These and related advances unify two proteolytic systems that have been studied separately over two decades.

Keywords: proteolysis, polyubiquitin, ubiquitylation, yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

The N-end rule relates the regulation of the in vivo half-life of a protein to the identity of its N-terminal residue1–18. N-terminal degradation signals (degrons) of the N-end rule pathway are called N-degrons. The main determinant of an N-degron is a destabilizing N-terminal residue of a protein. Recognition components of the N-end rule pathway are called N-recognins. In eukaryotes, an N-recognin is an E3 ubiquitin (Ub) ligase that can target a subset of N-degrons. A complex of an E3 N-recognin and its cognate E2 (Ub-conjugating) enzyme polyubiquitylates N-end rule substrates, targeting them for proteasome-mediated degradation (Fig. 1a). The term ‘Ub ligase’ denotes either an E2–E3 holoenzyme or its E3 component3,19–21.

Figure 1.

The Arg/N-end rule and UFD pathways. (a) The S. cerevisiae Arg/N-end rule pathway. See Introduction for terminology. N-terminal residues are indicated by single-letter abbreviations for amino acids. Yellow ovals denote the rest of a protein substrate. (b) The S. cerevisiae UFD (Ub-fusion degradation) pathway38,44,45. One class of UFD substrates are engineered protein fusions that have in common a ‘nonremovable’ N-terminal Ub moiety that acts as a degron38. Mgt1 is a physiological substrate of both the Arg/N-end rule and UFD pathways. A degron of Mgt1 is close to its N-terminus but is distinct from an N-degron12. Polyubiquitylation and degradation of Cup9 is mediated by the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex. (c) Both the Arg/N-end rule pathway and a subset of the UFD pathway are mediated by the Ubr1/Rad6-Ufd4/Ubc4 complex discovered in the present work. Also cited are physiological substrates of these pathways in S. cerevisiae. Mgt1 and Cup9 contain internal degrons5,12,22. The separase-produced fragment of the Scc1 subunit of cohesin contains an Arg-based N-degron3,6.

In eukaryotes, the N-end rule pathway comprises two major branches, one of which is termed the Arg/N-end rule pathway. It involves the N-terminal arginylation (Nt-arginylation) of protein substrates and also the targeting of unmodified hydrophobic and basic N-terminal residues (including Arg) by specific E3 N-recognins (Fig. 1a). The other branch, discovered in 2010, is termed the Ac/N-end rule pathway18. It involves the Nα -terminal acetylation (Nt-acetylation) of nascent proteins that bear either N-terminal Met or small uncharged residues (Ala, Val, Set, Thr or Cys). These residues become N-terminal after the cotranslational removal of Met by Met-aminopeptidases. Nt-acetylated proteins are targeted by the Ac/N-end rule pathway for polyubiquitylation and proteasome-mediated degradation18.

The Arg/N-end rule pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is mediated by the 225 kDa RING-type Ubr1 E3 Ub ligase (Fig. 1a). The type-1 and type-2 substrate-binding sites of Ubr1 recognize the unmodified basic (Arg, Lys, His) and bulky hydrophobic (Leu, Phe, Tyr, Trp, Ile) N-terminal residues, respectively3,11,22,23. The type-1 binding site of Ubr1 resides in the ~70-residue UBR domain3,17 that was recently solved at atomic resolution24–26. In addition to the type-1/2 sites, Ubr1 contains binding sites that recognize internal (non-N-terminal) degrons of proteins that include the Cup9 transcriptional repressor, the Mgt1 DNA repair protein (O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase)5,12,22,27, and misfolded proteins28–31. In contrast to the ‘primary’ destabilizing N-terminal residues (Arg, Lys, His, Leu, Phe, Tyr, Trp, Ile), the N-terminal residues Asp, Glu, Asn and Gln can be targeted by Ubr1 only after their Nt-arginylation by the Ate1 Arg-tRNA-protein transferase (R-transferase) (Fig. 1a). These destabilizing residues are called ‘secondary’ or ‘tertiary’, depending on the number of steps (arginylation of Asp and Glu; deamidation/arginylation of Asn and Gln) that precede the targeting and polyubiquitylation, by Ubr1, of Nt-arginylated N-end rule substrates8,10,15,16,32.

Regulated degradation of specific proteins by the Arg/N-end rule pathway mediates a legion of physiological functions, including the sensing of haem, nitric oxide, oxygen, and short peptides; the degradation of misfolded proteins; the fidelity of chromosome segregation; the regulation of DNA repair and peptide import; the signaling by G-coupled transmembrane receptors; the regulation of apoptosis, meiosis, fat metabolism, cell migration, cardiovascular development, spermatogenesis and neurogenesis; the functioning of adult organs, including the brain, muscle, testis and pancreas; and the regulation of leaf and shoot development, leaf senescence and seed germination in plants (refs. 3, 5, 6, 8–12, 15, 16, 18, 22, 28–35, and refs. therein). The recently discovered Ac/N-end rule pathway is likely to mediate, among other things, protein quality control and degradation of long-lived proteins18. Partial Nt-arginylation of apparently long-lived proteins such as β-actin and calreticulin36,37 suggests that Nt-arginylation may have nonproteolytic roles as well.

Our previous study showed that the S. cerevisiae Mgt1 DNA repair protein is co-targeted for degradation by the Ubr1/Rad6-mediated Arg/N-end rule pathway and the Ufd4/Ubc4-mediated Ub-fusion degradation (UFD) pathway12. Rad6 and Ubc4/Ubc5 are E2 enzymes that function with the E3s Ubr1 and Ufd4, respectively. Ufd4 is the 168 kDa HECT-type E3 of the UFD pathway38–43. The UFD pathway was discovered through analyses of N-terminal Ub fusions in which the Pro residue at the Ub-reporter junction or mutations of the Ub moiety were found to inhibit the cleavage of a fusion by deubiquitylases (DUBs)1,38,44,45. Such UFD substrates are targeted for polyubiquitylation and degradation through their N-terminal Ub moieties (Fig. 1b).

A priori, the number of topologically distinct poly-Ub chains can be very large, as all seven Lys residues of Ub can contribute, in specific in vivo contexts, to the synthesis of poly-Ub linked to protein substrates46,47. The delivery of ubiquitylated proteins to the 26S proteasome can be mediated by either K48-type, K11-type or K29-type chains, and possibly by poly-Ub of other topologies as well (refs. 3, 19, 46–48 and refs. therein). A single E3 can cooperate, in some settings, with two distinct E2 enzymes that mediate, sequentially, the synthesis of a substrate-linked poly-Ub chain49. Two E3s can also cooperate in producing a poly-Ub chain. Studies by Jentsch and colleagues45 (see also refs. 46, 50, 51 and refs. therein) introduced the concept of an E4 as an E3-like enzyme that cooperates with a specific E3 and its cognate E2 enzyme to increase the processivity of polyubiquitylation. Given the mechanistic and regulatory complexity of polyubiquitylation that remains to be understood, it would be constructive, at present, to define E4 operationally, as an E3-like enzyme that cooperates with a substrate-specific ubiquitylation machinery to increase the efficacy (including processivity) of polyubiquitylation, and in some cases to alter topology of a poly-Ub chain as well. This definition of E4 does not constrain its possible modes of action.

Here we report that the RING-type Ubr1 E3 and the HECT-type Ufd4 E3 interact, both physically and functionally. Using in vitro and in vivo approaches, we show that the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex mediates the Arg/N-end rule pathway and a part of the UFD pathway as well. Cooperation, in their physical complex, between Ubr1 and Ufd4 includes their ability to increase the processivity of polyubiquitylation of both Arg/N-end rule and UFD substrates, in comparison to targeting by Ubr1 or Ufd4 alone. Thus, operationally, the complex of Ubr1 and Ufd4 functions as an E3–E4 pair in which the ‘assignment’ of an E3 or E4 function depends on the substrate and the nature of its degron. We also found that Ubr1, similarly to Ufd4, contains a domain that specifically binds to N-terminal Ub but not to free Ub. S. cerevisiae lacking the Ufd4 component of the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex retained the Arg/N-end rule pathway but its proteolytic activity was lower than in wild-type cells. This could be seen not only with Arg/N-end rule substrates (i.e., substrates containing N-degrons) but also with Cup9, a transcriptional repressor of peptide import that is targeted by Ubr1 through an internal degron of Cup9. These and other results unified two proteolytic systems that have been studied separately over two decades.

RESULTS

Ubiquitylation of Mgt1 by Ubr1 and Ufd4

Although Mgt1 could be ubiquitylated (and subsequently degraded) by either the Arg/N-end rule or UFD pathways, strong polyubiquitylation of Mgt1 was observed only in the presence of both pathways12. To further address this interplay between Ubr1 and Ufd4, we employed a ubiquitylation assay that comprised 35S-labeled Mgt1f3 (C-terminally tagged with flag epitopes) that had been produced in reticulocyte extract12, and the following purified components: Ub; Uba1 (E1); Rad6 and/or Ubc4 (cognate E2s); Ubr1 and/or Ufd4; and ATP.

The assays were performed using wild-type Ub, UbK29R, UbK48R, or UbK63R, with Ub mutants of this set precluding formation of Ub-Ub isopeptide bonds of the K48, K29 or K63 topologies, respectively. Ubr1/Rad6 alone polyubiquitylated Mgt1 to comparable extents with either wild-type Ub, UbK29R, or UbK63R (Fig. 2, lanes 2, 3, 5). In contrast, little polyubiquitylation was observed with UbK48R (Fig. 2, lane 4), in agreement with evidence that Ubr1/Rad6 preferentially produces K48-type chains48. Together, Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4 polyubiquitylated Mgt1 both more strongly and more processively than Ubr1/Rad6 alone. Specifically, ubiquitylated 35S-Mgt1f3 produced with wild-type Ub and Ubr1/Rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4 migrated as high-yield polyubiquitylated derivatives in a narrow size range, ~200 kDa on average, corresponding to ~21 Ub moieties in a substrate-linked chain (Fig. 2, lane 7). In contrast, a broader distribution of much shorter chains was observed with Ubr1/Rad6 alone (Fig. 2, lane 2; cf. lane 7). When Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4 were assayed together in the presence of UbK29R, both high yield and processivity of Mgt1 polyubiquitylation were diminished, in comparison to results with wild-type Ub (Fig. 2, lane 8; cf. lanes 2, 3 and 7). When Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4 were assayed in the presence of UbK48R, the yield of Mgt1-linked chains was also much lower than with wild-type Ub, but their large average size and narrow size distribution were retained (Fig. 2, lane 9; cf. lanes 4 and 7). Similar results were obtained with Ufd4/Ubc4 alone, using either wild-type Ub or its mutants (Fig. 2, lanes 11–15). Thus, the presence of both Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4, and also of Ub containing wild-type Lys48 and Lys29 are required for the high-yield production of larger Mgt1-linked chains, and for their narrow size distribution as well (Fig. 2, lanes 7 and 10).

Figure 2.

Ubiquitylation of Mgt1 by Ubr1-Ufd4. The in vitro ubiquitylation assay12 is described in Methods. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30° C for 15 min, followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. 35S-Mgt1f3 and its polyubiquitylated derivatives are indicated on the right. Lane 1, Mgt1f3 in the complete reaction but without added Ub and with Ubr1 as the sole E3. Lane 2, same as lane 1 but with wild-type Ub. Lane 3, same as lane 1 but with UbK29R. Lane 4, same as lane 1 but with UbK48R. Lane 5, same as lane 1 but with UbK63R. Lane 6, S35-Mgt1f3 in the complete reaction (containing both Ubr1 and Ufd4) but without added Ub. Lane 7, same as lane 6 but with wild-type Ub. Lane 8, same as lane 6 but with UbK29R. Lane 9, same as lane 6 but with UbK48R. Lane 10, same as lane 6 but with UbK63R. Lane 11, Mgt1f3 in the complete reaction but without added Ub and with Ufd4. Lane 12, same as lane 11 but with wild-type Ub. Lane 13, same as lane 11 but with UbK29R. Lane 14, same as lane 1 but with UbK48R. Lane 15, same as lane 11 but with UbK63R.

Physical interaction between Ubr1 and Ufd4

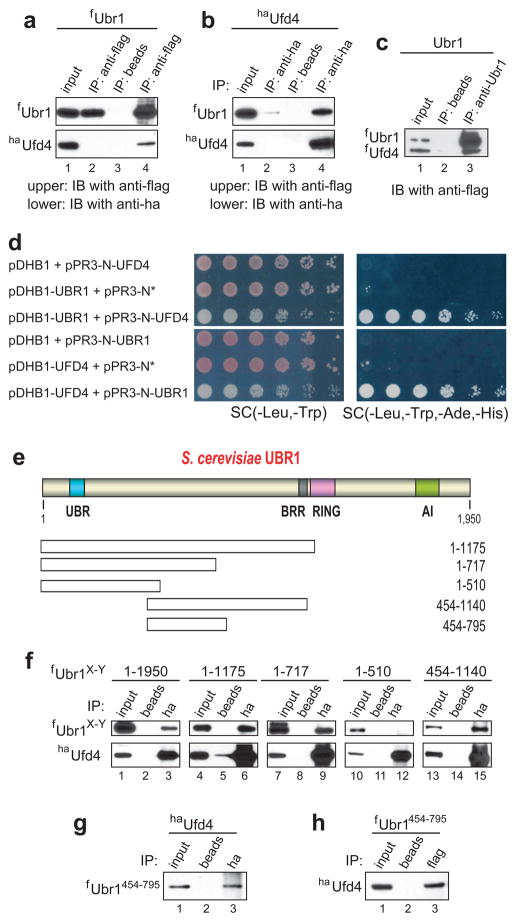

To test for a possible interaction between Ubr1 and Ufd4, we performed coimmunoprecipitations with extracts from cells expressing flag-tagged Ubr1 (fUbr1) and ha-tagged Ufd4 (haUfd4) (Fig. 3a–c). haUfd4 was coimmunoprecipitated with fUbr1 by anti-flag (Fig. 3a). Conversely, fUbr1 was coimmunoprecipitated with haUfd4 by anti-ha (Fig. 3b). To determine whether these results signified a direct interaction between Ubr1 and Ufd4, we also performed a coimmunoprecipitation with equal amounts of purified fUbr1 and fUfd4. The results (Figs. 3c and S1a) confirmed a direct interaction between Ubr1 and Ufd4.

Figure 3.

Physical interaction between Ubr1 and Ufd4. (a) Coimmunoprecipitation of fUbr1 and haUfd4 with anti-flag antibody. JD52 S. cerevisiae expressed N-terminally flag-tagged Ubr1 (fUbr1), either alone (lane 2) or together with N-terminally ha-tagged Ufd4 (haUfd4) (lanes 3 and 4). Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-flag (lanes 2 and 4) or with antibody-free beads (lane 3). The upper and lower panels show the results of immunoblotting with anti-flag (detection of fUbr1) and with anti-ha (detection of haUfd4), respectively. Lane 1, 1% input of extract from cells expressing both fUbr1 and haUfd4. Lane 2, extract from cells expressing only fUbr1 was incubated with anti-flag pre-bound to beads. Immunoblotting with anti-flag and anti-ha (upper and lower panels, respectively). Lane 3, extract from cells expressing both fUbr1 and haUfd4, but with beads lacking antibody. Lane 4, same as lane 3 but immunoprecipitation with anti-flag. (b) Same as in a but extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-ha pre-bound to beads (lanes 2 and 4) or with beads lacking antibody (lane 3), followed by SDS-PAGE of immunoprecipitates and immunoblotting with anti-flag and anti-ha. (c) Direct interaction of fUbr1 and fUfd4. Lane 1, 10% inputs of fUbr1 and fUfd4 (purified as described in ref. 12; see also Fig. S1a). fUbr1 (125 ng) and fUfd4 (125 ng) were mixed and incubated with beads lacking antibody (lane 2) or with previously characterized11 affinity-purified anti-Ubr1 antibody pre-bound to beads (lane 3), for 1 hr at 4° C in 0.25 ml of binding buffer, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-flag. (d) In vivo detection of Ubr1-Ufd4 interactions using split-Ub assay53. S. cerevisiae coexpressing bait (pDHB1, pDHB1-UBR1, or pDHB1-UFD4) and prey (pPR3-N*, pPR3-N-UFD4, or pPR3-N-UBR1) plasmids were grown to A600 of ~1, serially diluted (5-fold), and plated on either ‘permissive’ SC(-Leu, -Trp) (left column) or SC(-Leu, -Trp, -Ade, -His) medium (right column). pDHB1 and pPR3-N are the initial (vector) plasmids. pPR3-N* contained a stop codon immediately after the ORF encoding the mutant N-terminal half of Ub (NUb) in pPR3-N. (e) The UBR box, the BRR region, the RING domain, and the AI (autoinhibitory) domain of the S. cerevisiae Ubr1 N-recognin11,17,23. Fragments of Ubr1 employed to map its Ufd4-interacting region are below the diagram. (f) Extracts from JD52 S. cerevisiae that expressed haUfd4 and either full-length fUbr1 or its flag-tagged fragments were incubated with antibody-lacking beads (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11 and 14) or with anti-ha pre-bound to beads (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15). Bound proteins were eluted from washed beads, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-flag. Input lanes, samples of extracts that corresponded to 1% of initial extracts. (g) Coimmunoprecipitation of fUbr1454-795 and haUfd4 with anti-ha. Lane 1, 1% input of the initial extract. Lane 2, extracts from cells that expressed the fUbr1454-795 fragment and full-length haUfd4 were incubated with antibody-free beads (lanes 2). Bound proteins were eluted from washed beads and fractionated by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-flag. Lane 3, same as lane 2 but immunoprecipitation with anti-ha pre-bound to beads. (h) Lanes 1-3, same as lanes 1-3 in g, but immunoprecipitation with anti-flag (instead of anti-ha), followed by immunoblotting with anti-ha.

To examine the Ubr1-Ufd4 interaction in vivo, we employed the split-Ub technique52,53. Co-expression of Ubr1 as the bait and Ufd4 as the prey produced the interaction-positive Ade+ His+ phenotype reproducibly and robustly, whereas no Ade+ His+ cells were observed with negative controls (Fig. 3d). A reciprocal assay, with Ufd4 as the bait and Ubr1 as the prey, also indicated an in vivo interaction between Ubr1 and Ufd4 (Fig. 3d). To delineate the Ufd4-interacting region of Ubr1, coimmunoprecipitations (Fig. 3a, b) were carried out using anti-ha and extracts from S. cerevisiae that expressed full-length haUfd4 and one of the following Ubr1 fragments: fUbr1-1175, fUbr11-717, fUbr11-510, Ubr1454-1140f and fUbr1454-795 (Fig. 3e). haUfd4 was coimmunoprecipitated with all of these fragments except fUbr11-510 (Fig. 3f, g). A reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation with anti-flag confirmed that fUbr1454-795, encompassing 342 residues of the 1,950-residue Ubr1, could interact with haUfd4 (Fig. 3h).

Ufd4 contributes to ubiquitylation and degradation of Arg/N-end rule substrates

Since the degradation signal of Mgt1 is distinct from an N-degron12, we asked whether cooperation between Ubr1 and Ufd4 could also be detected with Arg/N-end rule substrates, i.e., with proteins containing N-degrons. Ubiquitylation of purified X-DHFRha (X=Met, Arg, Leu), a set of previously characterized Arg/N-end rule reporters based on the mouse dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) moiety and produced from Ub-X-DHFRha by the Ub fusion technique54,55 (Fig. S1b), was examined with wild-type Ub using either purified fUbr1/Rad6 alone, fUfd4/Ubc4 alone, or fUbr1/Rad6 plus fUfd4/Ubc4 (Fig. 4a). As expected38, Ufd4/Ubc4 alone did not polyubiquitylate Arg/N-end rule substrates (Fig. 4a, lanes 11 and 17), confirming that Ufd4 is not an N-recognin. As also expected5,23, Ubr1/Rad6 polyubiquitylated both Arg-DHFRha and Leu-DHFRha (type-1 and type-2 Arg/N-end rule substrates, respectively) but was virtually inactive with Met-DHFRha (Fig. 4a). Addition of Ufd4/Ubc4 to Ubr1/Rad6 resulted in longer substrate-linked poly-Ub chains (Fig. 4a), similarly to processivity enhancement that was observed with Mgt1 (Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

Enhancement of ubiquitylation and degradation of Arg/N-end rule substrates by Ufd4. (a) X-eK-DHFRha (X=Met, Arg, Leu), denoted as X-DHFRha, are C-terminally ha-tagged Arg/N-end rule reporters54 produced from Ub-X-DHFRha using in vitro deubiquitylation55 (Fig. S1b). X-DHFRha contained the mouse dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) moiety and the ~40-residue N-terminal extension called eK [extension (e) containing lysine (K)]18. Purified X-DHFRha (X=Met, Arg, Leu) (1.25 μM; 2 μl) were incubated in 20 μl of a ubiquitylation assay12 for 15 min at 30° C, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-ha. Lanes 1, 7, 13: X-DHFRha in the absence of indicated assay’s components. Lanes 2, 8, 14: same as lanes l, 7, 13 but with Rad6 E2. Lane 3, 9, 15, same as lanes 1, 7, 13 but with Ubr1 and Rad6. Lanes 4, 10, 16 same as lanes 1, 7, 13 but with Ubc4 E2. Lane 5, 11, 17 same as lane 1, 7, 13 but with Ufd4 and Ubc4. Lane 6, 12, 18 same as lane 1 but with Ubr1, Rad6, Ufd4 and Ubc4. Asterisk on the right denotes a protein that crossreacted with anti-ha antibody. (b) Same as in a but the assay was carried out with Arg-DHFRha and indicated Ub mutants. Detection of immunoblotted proteins in this experiment was performed using Odyssey (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA). Asterisks on the left indicate two bands of proteins (e.g., lanes 1, 4) that crossreacted with anti-ha, and were also present in samples lacking E2s and E3s. Lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, ubiquitylation of Arg-DHFRha with Ufd4/Ubc4 in the presence of either UbK29 (lane 1), UbK48 (lane 4), a 50-50 mixture of UbK29 and UbK48 (lane 7), UbK29R (lane 10), UbK48R (lane 13), or a 50-50 mixture of UbK29R and UbK48R (lane 16). Lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, same as lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, respectively, but with Ubr1/Rad6 instead of Ufd4/Ubc4. Lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, same as lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, respectively, but with Ubr1/Rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4. (c) Lanes 1 and 2, molecular mass markers and Coomassie-stained proteins of the affinity-purified S. cerevisiae 26S proteasome, respectively. (d) Lanes 1–3, assay with 26S proteasome and polyubiquitylated Leu-DHFRha that had been prepared using Ubr1/Rad6 alone, with chase times of 10 and 20 min. Lanes 4–6, same as lanes 1–3, but with polyubiquitylated Leu-DHFRha that had been prepared with Ubr1/Rad6 plus and Ufd4/Ubc4. (e) Quantitation of data in d, using ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html). In plotting the levels of Leu-DHFRha for each data set (lanes 1–3 and 4–6 in d), the levels at time zero were taken as 100%. Open and closed circles, Leu-DHFRha that had been ubiquitylated by Ubr1/Rad6 and by Ubr1/Rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4, respectively.

Ubiquitylation assays were also carried out with Arg-DHFRha and the Ub mutants UbK29 (Ub in which all lysines except K29 were replaced by Arg) (Fig. 4b, lanes 1–3); UbK48 (Ub in which all lysines except K48 were replaced by Arg) (Fig. 4b, lanes 4–6); an equimolar mixture of UbK29 and UbK48 (Fig. 4b, lanes 7–9); UbK29R (Ub in which one lysine, K29, was replaced by Arg) (Fig. 4b, lanes 10–12); UbK48R (Ub in which one lysine, K48, was replaced by Arg) (Fig. 4b, lanes 13–15); and an equimolar mixture of UbK29R and UbK48R (Fig. 4b, lanes 16–18). There was virtually no polyubiquitylation of Arg-DHFRha by Ufd4/Ubc4 alone in the presence of any Ub mutant (Fig. 4b, lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16), in agreement with Ufd4 not being an N-recognin. In contrast, Ubr1/Rad6 polyubiquitylated Arg-DHFRha in the presence of either UbK29R, UbK48R, or both of them together (Fig. 4b, lanes 11, 14 and 17, cf. lanes 10, 13 and 16, respectively). To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that Ubr1/Rad6 can produce, at least in vitro, non-K48 poly-Ub chains. Similarly to results with wild-type Ub (Fig. 4a, lane 12; cf. lane 9), both the yields and average sizes of substrate-linked poly-Ub chains were significantly larger in the presence of Ubr1/Rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4, using either UbK29R, UbK48R, or two of them together (Fig. 4b, lanes12, 15 and 18; cf. lanes 11, 14 and 17).

With UbK29, either Ubr1/Rad6 alone or Ubr1/Rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4 could produce only short poly-Ub chains, i.e., no significant increase in processivity was observed with Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4 together (Fig. 4b, lanes 2, 3). It is possible that UbK29 was too perturbed by six mutations to be an efficacious substrate for polyubiquitylation by Ubr1/Rad6-Ufd4/Ubc4. In contrast, with UbK48 (only K48-type chains could be produced with this Ub mutant), there was a significant increase in the yield and processivity of polyubiquitylation in the presence of Ubr1/Rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4 (Fig. 4b, lanes 5, 6; cf. lanes 2, 3 and 11, 12). In one model that is consistent with our findings (Figs. 2 and 4a, b), a physical interaction between Ubr1 and Ufd4 (Fig. 3) increases, allosterically, the efficacy and processivity of the Ubr1/Rad6 Ub ligase that is bound to Ufd4/Ubc4. In another plausible model, the Ufd4/Ubc4 component of the Ubr1/Rad6-Ufd4/Ubc4 complex may utilize a specific Lys residue of Ub (e.g., Lys48; see above) to elongate a poly-Ub chain that had been initiated (‘primed’) by Ubr1/Rad6.

We also employed a degradation assay with the purified 26S proteasome56 (Fig. 4c). The in vitro half-lives of Leu-DHFRha that had been polyubiquitylated by Ubr1 alone versus Ubr1 plus Ufd4 were ~23 min versus ~7 min, respectively (Fig. 4d, e). To increase the yields of polyubiquitylated reporters before the addition of the 26S proteasome, ubiquitylation was carried out for 18 hr at 30°C, as opposed to 15 min in the assay of Fig. 4a (lanes 13–18), resulting in the absence of non-ubiquitylated Leu-DHFRha and most likely accounting for a marginal difference, in this experiment, between the longest chains in the presence of Ubr1 versus Ubr1 plus Ufd4 (Fig. 4d, lanes 1 and 4). In addition to effects of poly-Ub chains, the faster degradation of polyubiquitylated Leu-DHFRha that had been produced by Ubr1-Ufd4 (Fig. 4d, e) may also stem from previously described (and possibly synergistic) interactions of Ubr1 and Ufd4 with the 26S proteasome41,42. These issues await more detailed studies with proteasome-based assays.

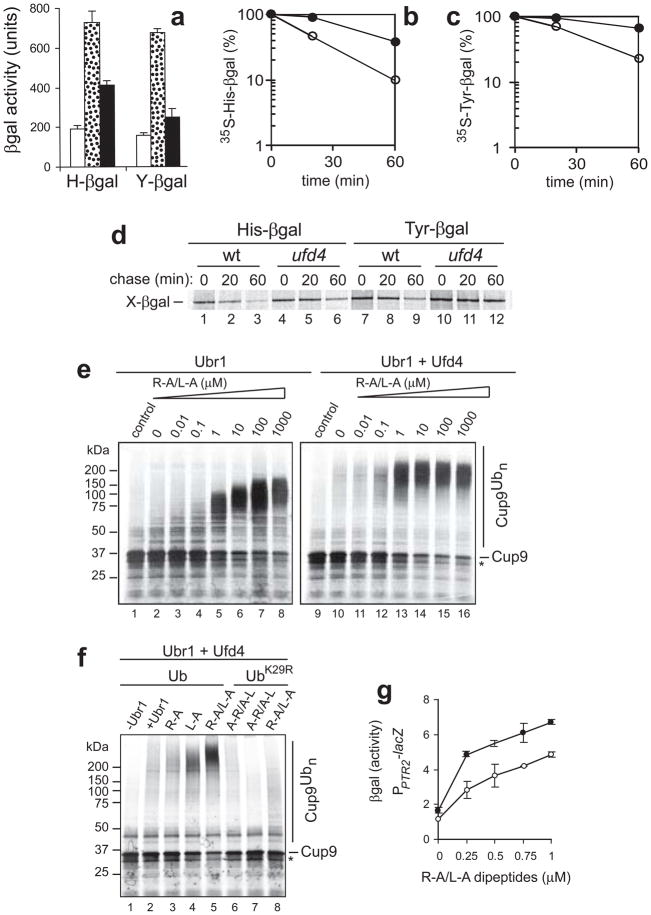

To determine whether the in vitro effect of Ufd4 on Arg/N-end rule substrates (Fig. 4) occurred in vivo as well, we employed X-β-galactosidase (X-β gal) reporters, produced by the cotranslational deubiquitylation of Ub-X-β gal (X=His, Tyr)1,57. The activity of β gal in extracts from cells that express X-β gal is a reliable measure of the reporter’s metabolic stability54. In agreement with in vitro data (Fig. 4), His-βgal and Tyr-βgal became partially stabilized in the absence of Ufd4 (Fig. 5a). 35S-pulse-chases confirmed these results: the in vivo half-life of His-β gal was ~18 min in wild-type cells and doubled to ~41 min in ufd4Δ cells (Fig. 5b, d). The in vivo half-life of Tyr-β gal was ~28 min in wild type cells and ~99 min in ufd4Δ cells (Fig. 5c, d). Half-lives of X-β gals in ubr1Δ cells exceeded 20 h (data not shown), in agreement with earlier data1,3.

Figure 5.

Ufd4 augments the Arg/N-end rule pathway. (a) β gal activity in extracts from S. cerevisiae RJD347 (wild-type; white bars), AVY26 (ubr1Δ; dotted bars), and CHY251 (ufd4Δ; black bars) that expressed His-β gal or Tyr-β gal. (b ,c ) Quantitation of data (using PhosphorImager) in a pulse-chase assay (d) for His-β gal (b) and Tyr-β gal (c). Open and closed circles, wild-type (RJD347) and ufd4Δ (CHY251) cells, respectively. In d, S. cerevisiae expressing Ub-His-β gal or Ub-Tyr-β gal were labeled for 5 min with 35S-methionine/cysteine, followed by a chase for 20 and 60 min, immunoprecipitation with anti-β gal, SDS-PAGE and autoradiography1,54. Lanes 1–3, His-β gal in wild-type cells. Lanes 4–6, His-β gal in ufd4Δ cells. Lanes 7–9, Tyr-β gal in wild-type cells. Lanes 10–12, Tyr-β gal in ufd4Δ cells. (e) Ubr1/Rad6-mediated polyubiquitylation of Cup9. In vitro ubiquitylation assay12 was performed with 35S-labeled Cup9NSF (see Methods). Lane 1, 35S-Cup9 in an otherwise complete assay but without E3s. Lanes 2–8, same as lane 1 but with Ubr1/Rad6, in the presence of Arg-Ala (R-A)/Leu-Ala (L-A). Lane 9, same as lane 1 but a separate assay. Lanes 10–16, same as lanes 2–8, but with Ubr1 plus Ufd4. (f) Maximal stimulation of Cup9 ubiquitylation by Ubr1-Ufd4 requires both type-1 and type-2 dipeptides. Lane 1, 35S-Cup9, with Ufd4 and wild-type Ub, but in the absence of both Ubr1 and type-1/2 dipeptides. Lane 2, same as lane 1 but with Ubr1. Lane 3, same as lane 2, but with 1 μM R-A. Lane 4, same as lane 2 but in the presence of 1 μM L-A. Lane 5, same as lane 2, but in the presence of R-A and L-A, each at 1 μM. Lane 6, same as lane 2 but in the presence of Ala-Arg/Ala-Leu, each at 1 μM. Lanes 7, same as lane 6, but with UbK29R, instead of wild-type Ub. Lane 8, same as lane 7, but in the presence of R-A/L-A, each at 1 μM. (g) Dipeptide-mediated induction of the PTR2 transporter in the absence or presence of Ufd4. S. cerevisiae RJD347 (wild-type; closed circles) and CHY251 (ufd4Δ; open circles) expressed E. coli lacZ (β-galactosidase) from the PPTR2 promoter. Cells were grown to A600 of ~0.8 in the SHM medium at 30° C in the presence of indicated concentrations of R-A/L-A, followed by measurements in triplicate, of β gal activity in cell extracts, with standard deviations shown.

Ufd4 contributes to regulation of peptide import by the Arg/N-end rule pathway

The binding of short peptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues to the type-1/2 sites of Ubr1 (see Introduction) allosterically activates the third substrate-binding site of Ubr1 that recognizes an internal degron of Cup9, a transcriptional repressor5,22. Genes down-regulated by Cup9 include PTR2, which encodes the transporter of di- and tripeptides33. This positive-feedback circuit, in which Cup9 degradation is induced by type-1/2 peptides, allows S. cerevisiae to sense the presence of extracellular peptides and to react by accelerating their uptake5,22,27. In agreement with earlier findings5,23, ubiquitylation assays with 35S-labeled Cup9 and Ubr1/Rad6 showed that low-μM levels of the type-1/2 dipeptides Arg-Ala/Leu-Ala greatly increased the Ubr1-mediated polyubiquitylation of Cup9 (Fig. 5e, lanes 1–8). Ufd4/Ubc4 plus Ubr1/Rad6 significantly increased the processivity of Cup9 polyubiquitylation at an even lower (0.1 μM) concentration of the same dipeptides (Fig. 5e, lanes 12, 13). Moreover, in the presence of Ufd4/Ubc4 plus Ubr1/Rad6, dipeptides increased the average size of Cup9-linked poly-Ub chains, in comparison to chains (at the same levels of dipeptides) by Ubr1/Rad6 alone (Fig. 5e, lane 14; cf. lane 5). The effect of dipeptides required the presence of both type-1 and type-2 dipeptides together, and also the presence of Ub that was able to form K29-type chains (Fig. 5f).

In vivo induction of the transporter Ptr2 by low-μM levels of Arg-Ala/Leu-Ala dipeptides5,23 was diminished in the absence of Ufd4 (Fig. 5g), in agreement with in vitro results (Fig. 5e, f). To determine whether Ufd4 contributes to degradation of Cup9 in vivo, we employed the Ub-reference technique (URT), a method that increases the accuracy of a pulse-chase assay by providing a ‘built-in’ reference protein5,27,54 (see the legend to Fig. S2a, b). In agreement with other data (Fig. 5e-g), the in vivo half-life of Cup9 was ~5 min in wild-type cells and ~14 min in ufd4Δ cells (Fig. S2a, b).

The Ubr1-Ufd4 complex and the UFD pathway

Ufd4, as a part of the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex, augments the Ubr1-based Arg/N-end rule pathway (Figs. 4 and 5). Might Ubr1 have a ‘reciprocal’ effect on the Ufd4-mediated UFD pathway? We employed a ubiquitylation assay with purified UFD substrates such as Ub-ProtA (Protein A) and Ub-GST (glutathione S-transferase) (Fig. S1c). As expected38,45, the cognate Ufd4/Ubc4 Ub ligase of the UFD pathway ubiquitylated, with a low processivity, both Ub-ProtA and Ub-GST (Fig. 6a, b, lanes 3; cf. lanes 1). Remarkably, the Ubr1/Rad6 Ub ligase of the Arg/N-end rule pathway could also ubiquitylate (with a low processivity) these UFD substrates in the absence of Ufd4 (Fig. 6a, b, lanes 2; cf. lanes 1). Moreover, the processivity of polyubiquitylation of Ub-ProtA and Ub-GST was strongly increased in the presence of both Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4 (Fig. 6a, b, lanes 4; cf. lanes 1–3). Ufd2, an E4-type enzyme of the UFD pathway38,45,58,59, also increased the processivity of the Ufd4 E3 in this system (Fig. 6a, b, lanes 7; cf. lanes 1–3, 5). However, in contrast to Ufd4, Ufd2 had only a weak effect on ubiquitylation by Ubr1 (Fig. 6a, b, lanes 6; cf. lanes 1–3, 5). In sum, Ufd4 and Ubr1 can function as mutually cooperative, physically interacting E3 enzymes not only with Arg/N-end rule substrates but with UFD substrates as well. To gauge the extent of substrate specificity of Ubr1 and Ufd4 in these assays (Figs. 2, 4a, b, 5e, f, and 6a, b), we asked whether an unrelated substrate could be ubiquitylated by Ubr1 and/or Ufd4. These experiments employed purified Sic1PY (Fig. S1c), an engineered substrate of the Rsp5 E3 Ub ligase. Whereas purified Rsp5 (with the cognate Ubc4 E2) polyubiquitylated Sic1PY, neither Ubr1/Rad6 nor Ufd4/Ubc4 could utilize Sic1PY as a substrate (Fig. 6e).

Figure 6.

Recognition and synergistic polyubiquitylation of UFD substrates by Ufd4 and Ubr1. (a) Ubiquitylation assay12, for 15 min at 30° C, with Ub-ProtA, a UFD substrate (0.125 μM) (Fig. S1c), followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-ProtA antibody. Lane 1, without E3s. Lane 2, same as lane 1 but with Ubr1/Rad6. Lane 3, same as lane 1 but with Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 4, same as lane 1 but with Ubr1/Rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 6, same as lane 1 but with Ufd2/Ubc4 plus Ubr1/Rad6. Lane 7, same as lane 1 but with Ufd2/Ubc4 plus Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 8, same as lane 1 but with Ufd2/Ubc4, Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4. (b) Ubiquitylation assay with Ub-GST (0.125 μM). Lane 1, Ub-GST without E3s. Lane 2, same as lane 1 but with Ubr1/Rad6. Lane 3, same as lane 1 but with Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 4, same as lane 1 but with Ubr1/Rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 5, same as lane 1 but with Ufd2/Ubc4. Lane 6, same as lane 1 but with Ufd2/Ubc4 plus Ubr1/Rad6. Lane 7, same as lane 1 but with Ufd2/Ubc4 plus Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 8, same as lane 1 but with Ufd2/Ubc4, Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4. (c) Interaction of Ubr1 with immobilized UFD substrates could be competed out by UFD substrates but not by free Ub. Equal amounts of purified fUbr1 (1 μg) were incubated (in either the presence or absence of free Ub, Ub-DHFRha (Ub-Met-DHFRha) or Ub-ProtA, each of them at 1 or 10 μM)) with GST alone or Ub-GST (~5 μg) that had been linked to glutathione-Sepharose beads. Bound proteins were eluted from the beads, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-flag (upper panel), with subsequent Coomassie staining of the blotted PVDF membrane (lower panel). Lane 1, GST alone. Lane 2, Ub-GST. Lane 3, same as lane 2 but in the presence of 1 μM free Ub. Lane 4, same as lane 2 but with 10 μM free Ub. Lane 5, same as lane 2 but in with 1 μM Ub-DHFRha. Lane 6, same as lane 2 but with 10 μM Ub-DHFRha. Lane 7, same as lane 2 but with 1 μM Ub-ProtA. Lane 8, same as lane 2 but with 10 μM Ub-ProtA. (d) In vivo levels of endogenous Ubr1. Lanes 1–6, a dilution series with the indicated amounts of purified fUbr1 was fractionated by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with affinity-purified anti-Ubr1 antibody11. Lane 7, extract (50 μg) from wild-type S. cerevisiae (JD52) that grew exponentially (A600 of ~1) in YPD medium. Lane 8, same as lane 7 but extract from ubr1Δcells (JD55). These data and straightforward calculations indicated that ‘wild-type’, haploid, exponentially growing S. cerevisiae contained 500 to 1,000 Ubr1 molecules per cell. (e)Ubr1 and Ufd4 did not affect the Rsp5-mediated polyubiquitylation of T7 epitope-tagged Sic1PY. The PY motif is the sequence Pro-Pro-X-Tyr, which binds to the WW domain of Rsp5 (see Methods). Purified Sic1PY (Fig. S1c) was incubated in the above ubiquitylation assay, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-T7 antibody. Lane 1, Sic1PY without E3s. Lane 2, same as lane 1 but with Ubr1/Rad6. Lane 3, same as lane 1 but with Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 4, same as lane 1 but with Ubr1/rad6 plus Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 5, same as lane 1 but with Rsp5/Ubc4. Lane 6, same as lane 1 but with Rsp5/Ubc4 and Ubr1/Rad6. Lane 7, same as lane 1 but with Rsp5/Ubc4 plus Ufd4/Ubc4. Lane 8, same as lane 1 but with Rsp5/Ubc4, Ubr1/Rad6 and Ufd4/Ubc4. (f, g) Equal amounts of cells from wild-type (JD52), ubr1Δ (JD55), ufd4Δ (CHY194) or ubr1Δufd4 Δ (CHY195) strains were 5-fold serially diluted, plated on YPD plates containing 6% ethanol (6%) (f) or canavanine at 0.4 mg/ml (g), and incubated at 30° C for 3 days and 1 day, respectively.

Because Ubr1 could ubiquitylate UFD substrates in the absence of Ufd4 (Fig. 6a, b), we asked whether Ubr1 contained a Ub-binding site. GST-pulldowns showed that the binding of fUbr1 to Ub-GST could be efficaciously competed out by other UFD-type fusions such as Ub-ProtA or Ub-Met-DHFRha, whereas a large molar excess of free Ub did not significantly decrease the binding of fUbr1 to Ub-GST (Fig. 6c). Thus Ubr1 contains a previously overlooked Ub-binding site that can distinguish between conjugated and free Ub (Fig. 6c), analogously to a Ub-binding site of the Ufd4 E3 Ub ligase40.

Neither Ubr1 nor Ufd4 are essential proteins under normal growth conditions3,38. Both ufd4Δand ubr1Δ mutants were moderately hypersensitive to treatments that increased protein misfolding, such as 6% ethanol or canavanine, an analog of arginine45 (Fig. 6f, g). Interestingly, ubr1Δ ufd4Δ double mutants were much more sensitive to ethanol or canavanine than their single-mutant counterparts (Fig. 6f, g), in agreement with demonstrated interactions and interdependence between the Arg/N-end rule and UFD pathways.

Given the in vivo interaction between Ubr1 and Ufd4 (Fig. 3), we wished to determine their approximate molar ratio in wild-type cells. Previous work indicated that haploid S. cerevisiae contained ~7300 Ufd4 molecules per cell60, but there was no information about Ubr1 levels in that study or elsewhere. To estimate in vivo levels of Ubr1, we immunoblotted extracts of wild-type S. cerevisiae using the previously characterized, affinity-purified anti-Ubr1 antibody11 and calibrated these assays with known amounts of purified fUbr1. The results (Fig. 6d) indicated that ‘wild-type’, haploid S. cerevisiae in YPD medium contained 500 to 1,000 Ubr1 molecules per cell. Thus Ubr1 is ~10-fold less abundant than the Ufd4, suggesting a minor contribution of Ubr1 to the activity of the UFD pathway. Indeed, no significant decrease in the rate of degradation of UbV76-Val-β gal, a UFD substrate, was observed in ubr1ΔS. cerevisiae , whereas in ufd4Δ cells this UFD reporter was nearly completely stabilized (Fig. S2c, d).

DISCUSSION

The Arg/N-end rule and UFD pathways have been studied separately for more than two decades1,3,38,40,44,45. In 2009, we found that an internal degron of S. cerevisiae Mgt1 was co-targeted by the Arg/N-end rule and UFD pathways12. We now report that the Arg/N-end rule pathway is mediated by a physical complex of the RING-type Ubr1 E3 and the HECT-type Ufd4 E3, together with their cognate E2 enzymes Rad6 and Ubc4/Ubc5, respectively (Fig. 1c). The earlier examples of a complex between a RING-type E3 and a HECT-type E3 are distinct from the present case. Specifically, the complexes of the RING-type CBLC E3 with the HECT-type AIP/ITCH E3 and of the RING-type Rnf11 E3 with the HECT-type WWP1 E3 remain to be analyzed functionally61,62. Furthermore, specific HECT-type E3s were shown to bind RING-type E3s and target them for polyubiquitylation and degradation63,64, in contrast to Ubr1-Ufd4 (Fig. 1c), where intra-complex targeting has not been observed, thus far. Multicellular eukaryotes contain functionally overlapping E3 N-recognins that are sequelogous (similar in sequence)65 to yeast Ubr1, in part because they contain the UBR domain3,17,24–26. Trip12, a human HECT-type E3, is a sequelog65 of S. cerevisiae Ufd4 and mediates degradation of human UFD substrates66. Thus our results with yeast Ubr1-Ufd4 are likely to be relevant to all eukaryotes.

S. cerevisiae Ufd4 is not an N-recognin, i.e., it does not, by itself, recognize N-degrons, in contrast to Ubr1 (Fig. 4a, b). But through its physical interaction with the Ubr1 E3, the Ufd4 E3 functions as a novel component of the Arg/N-end rule pathway that increases the efficacy of Ubr1, at least in part by augmenting the processivity of polyubiquitylation of Arg/N-end rule substrates (Fig. 1a, c). Interestingly, the function of Ufd4 in the Arg/N-end rule pathway is broader than that of a processivity-enhancing component of the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex because Ufd4 can target the internal degron of Mgt1 even in ubr1Δcells 12. Although Ufd4 is not strictly essential for the ability of Ubr1 to mediate the Arg/N-end rule pathway, this pathway is detectably impaired in ufd4Δ cells (Figs. 5a–d and S2a, b).

As mentioned above, Ufd4 does not recognize N-degrons but functions to increase the processivity of polyubiquitylation of Arg/N-end rule substrates. Conversely, Ubr1 can function as a processivity-increasing component of the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex in its polyubiquitylation of UFD substrates. Moreover, Ubr1 recognizes the N-terminal Ub moiety of UFD substrates (Fig. 6c). Thus Ubr1 can bind to such substrates independently of Ufd4. Because Ubr1 is ~10-fold less abundant than Ufd4 in wild-type cells (see Results), the Ubr1/Rad6-Ufd4/Ubc4 complex is expected to mediate the bulk of the Arg/N-end rule pathway, whereas the same complex mediates only a subset of the UFD pathway (Fig. 1).

Given the existence of the Ubr1-Ufd4 complex, it is possible that some functions of Ubr1 might be mediated by its functionally relevant associations with other, non-Ufd4 E3s as well, for example with San1, a nuclear E3 Ub ligase that recognizes misfolded proteins67. In addition, the molar excess of Ufd4 relative to Ubr1 in vivo suggests that Ufd4 might also interact with other E3s. One possibility is that the UFD pathway comprises a dynamic ‘mosaic’ of reversible binary Ufd4 complexes with several E3s, including Ubr1. These are just some of the ramifications suggested by results of the present study, which unified, in a novel way, two multifunctional proteolytic systems (Fig. 1).

METHODS

Yeast strains, media, genetic techniques, and β-galactosidase assay

S. cerevisiae strains are described in Table S1. Standard techniques were employed for strain construction and transformation. The strains CHY233 and CHY251 (Table S1) were constructed by PCR-mediated gene disruption of UFD4 in S. cerevisiae RJD347, using the pFA6a-KanMX6 plasmid68. S. cerevisiae media included YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose; only most relevant media components are cited); SD medium (0.17% yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose); SRGal medium (0.17% yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 2% raffinose, 2% galactose); SHM medium (0.1% allantoin, 2% glucose, 0.17% yeast nitrogen base); and synthetic complete (SC) medium (0.17% yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose, plus a drop-out mixture of compounds required by a given auxotrophic strain). Assays for β-galactosidase (β gal) activity in yeast extracts were carried out using Yeast β-Galactosidase Assay Kit (Thermo scientific, Rockford, IL). S. cerevisiae strains that expressed His-β gal or Tyr-β gal were prototrophic for all 20 amino acids and were grown in a minimal medium in the absence of amino acids, to bypass the previously characterized activation of the Ubr1/Rad6 Ub ligase by added amino acids11,27.

Plasmids

They are described in Table S2. In the high copy (2μ-based) pCH522 plasmid, fUbr11-510 (N-terminally tagged with flag) was expressed from the PADH1 promoter. To construct pCH522, a region of the UBR1 ORF was PCR-amplified from pFlagUBR1SBX using the primers OCH820 (ACACCATGGACTACAAGGACGAT GATGACAAGGGTTCTATGTCCGTTGCTGATGATGATTTA; the NcoI site is underlined) and OCH518 (AAACTCGAGCTAATCAAAATAAAGAATATGTTGTAA; the XhoI site is underlined). The resulting DNA fragment was digested with NcoI/XhoI and subcloned into NcoI/XhoI-cut pNTFlag717UBR1. The plasmids pCH230, pCH231, pCH232, which encoded His10-Ub-X-DHFRha (X=Met, Arg, Leu), were constructed by ligating NdeI/HindIII-digested pEJJ1-M, pEJJ1-R, and pEJJ1-L, respectively38, into the NdeI/HindIII-cut pH10UE plasmid10. Construction details for other plasmids (Table S2) are available upon request. All final constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Yeast-based split-ubiquitin assay

A version of split-Ub assay52 used was described53. The bait S. cerevisiae proteins Ubr1 and Ufd4 were cloned via SfiI sites downstream of the OST4 sequence into pDHB1. The prey proteins were cloned downstream of the NubG-coding segment into prey vector pPR3-N using full-length UBR1 and UFD4 ORFs. All constructs were verified by sequencing. S. cerevisiae NMY51 (MATa trp1 leu2 his3 ade2 LYS2::lexA-HIS3 ade2::lexA-ADE2 URA3::lexA-lacZ) (Dualsystems Biotech AG, Schlieren, Switzerland) was cotransformed with bait and prey plasmids using the lithium acetate method69. Transformants were selected for the presence of bait and prey plasmids during 3 days of growth at 30°C on SC(-Trp, -Leu) medium (minimal medium containing 2% glucose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% bacto-agar, and complete amino acid mixture lacking Leu and Trp). Several colonies were transferred to liquid SC(-Trp, -Leu) and grown overnight to A600 of ~1. Five-fold serial dilutions were spotted onto SC(-Trp, -Leu) and SC(-Trp, -Leu, -His, -Ade) plates53 and grown for 2 days at 30°C.

Immunoblotting, coimmunoprecipitation, and GST-pulldown assays

Whole yeast cell extracts were prepared using a modification of Kushnirov’s method11,18,70. Immunoblotting was performed as described11,12,18. Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays with fUbr1 and haUfd4 were carried out as follows. Extracts (0.2 mg) from JD52 S. cerevisiae that co-expressed, from indicated plasmids, the full-length haUfd4 and either full-length fUbr1 (pFlagUBR1SBX), fUbr11-1175 (pFlagUBR1NT1-1175), fUbr11-717 (pFlagUBR1NT1-717), fUbr11-510 (pCH522), or fUbr1454-795 (pCH487), were immunoprecipitated using anti-ha antibody and protein G-magnetic beads (Invitrogen) in lysis buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) containing the above-cited protease-inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Bound proteins were eluted from thrice-washed beads in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer, followed by SDS-4-12% NuPAGE, and immunoblotting with anti–ha or anti-flag. In a different assay, purified fUbr1 (0.125 μg) and fUfd4 (0.125 μg) were incubated together for 2 h at 4°C in 0.25 ml of reaction buffer (10% glycerol, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 0.5 mM EDTA 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5), followed by immunoprecipitation with affinity-purified anti-Ubr1 antibody (1 μg)11 pre-bound to Protein A immobilized on magnetic beads (Invitrogen). Bound proteins were washed 4 times in 0.5 ml of the same buffer, followed by SDS-4-12% NuPAGE and immunoblotting with anti-flag. In the assay for a direct interaction between purified fUbr1 and fUfd4 (see Fig. 3c), immunoprecipitates were washed three times in the binding buffer, followed by elution of retained proteins, SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting with anti-flag.

GST pulldown assays with purified fUbr1 were carried out using a slight modification of the earlier procedure22. Either GST alone or Ub-GST fusion proteins (5 μg) were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads (15 μl; 50% slurry) in 0.5 ml of GST-loading buffer (10% glycerol, 0.5 M NaCl, 1% NP40, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) for 20 min at 4° C. The beads were washed once with 0.5 ml of GST-binding buffer (10 % glycerol, 0.05% NP40, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.8). Washed beads in 0.25 ml of GST-binding buffer were incubated with 1 μl of purified fUbr1 (1 μg) in the absence or presence of 1 (or 10) μM Ub, Ub-ProtA, or Ub-Met-DHFRha at 4° C for 1 h. Beads-associated proteins were eluted and fractionated by SDS-4-12% NuPAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-flag. Blots were also Coomassie-stained, to verify the expected amounts of GST fusions pre-bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads.

Production and purification of X-DHFRha test proteins

The plasmids pCH230, pCH231, pCH232, which encoded His10-Ub-X-DHFRha (X=Met, Arg, Leu)54,55 (see also the legend to Fig. 4) were transformed into KSP22 (aatΔ) E. coli . Purification of these fusions and their in vitro deubiquitylation55 were carried as described previously15.

Pulse-chases

35S-pulse-chase experiments, with 5-min pulses and chases of 20 and 60 min (Fig. 5b, d) were performed as described11,12,23, using S. cerevisiae JD52, JD55 (ubr1Δ), CHY194 (ufd4Δ) or CHY195 (ubr1Δ ufd4Δ) that carried plasmids expressing either UbV76-Val-βgal, Ub-His-βgal, Ub-Tyr-βgal, or fDHFR-UbK48R-Cup9NSF (the latter from the plasmid p416fUPRCUPNSF; see the legend to Fig. S2).

In vitro ubiquitylation assay

Unless indicated otherwise, in vitro ubiquitylation assays were carried out as described 12. Purified S. cerevisiae Uba1 (E1 enzyme) as well as Ub and its mutant derivatives were from BostonBiochem. The S35-labelled Mgt1 and Cup9 test proteins were expressed as described12 for Mgt1, using the in vitro transcription/translation TNT T7 Quick for PCR DNA system, derived from rabbit reticulocyte extract (Promega). Thus far, we could not produce soluble Mgt1 (a relatively hydrophobic protein) in E. coli. All experiments with Cup9 utilized Cup9NSF, a previously characterized missense mutant that exhibited reduced specific binding to DNA, reduced toxicity in vivo, but no significant changes in the kinetics of in vivo degradation5. The unlabeled Ub-ProtA, Ub-GST or Sic1PY test proteins, purified from E. coli (see above), were examined in ubiquitylation assays directly, whereas purified X-DHFRha proteins (X=Met, Arg, Leu) were incubated, at first, with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM; 5 mM) for 5 min at 30° C to inactivate traces of the remaining Usp2-cc DUB, followed by removal of NEM, using Zeba desalting columns (Thermo Scientific). 2 μ1 of either 35S-labeled Mgt1, S35-labeled Cup9, unlabeled, purified X-DHFRha (X=Met, Arg, Leu), Ub-ProtA, Ub-GST, or Sic1PY were incubated with purified fUbr1, fUfd4, Rad6, and/or Ubc4 at 30° C for 15 or 30 min in 20 μl of the final reaction sample (4 mM ATP, 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) containing 100 nM Uba1 and 80 μM Ub. The final concentrations of other purified proteins (if present in the assay) were as follows: 125 nM X-DHFRha; 125 nM Ub-ProtA; 125 nM Ub-GST; 125 nM Sic1PY; 200 nM fUbr1; 200 nM fUfd4; 1 μM Rad6; 1 μM Ubc4. The reactions were terminated by adding 8 μl of 4xSDS-sample buffer. The samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min, followed by SDS-4–12% NuPAGE and either autoradiography or immunoblotting with antibodies to the ha epitope (1:2,000; mouse monoclonal antibody; Sigma); to ProtA (polyclonal rabbit antibody; 1:10,000) (Sigma); to GST (polyclonal rabbit antibody; 1:10,000) (ZYMED Laboratories); and to the T7 epitope (polyclonal rabbit antibody; 1:10,000) (Novagen).

Purification of the 26S proteasome and degradation assay

A slight modification of the earlier procedure56 was employed. S. cerevisiae YYS40, in which the Rpn11 subunit of the 26 proteasome contained a triple-flag tag, were grown to A600 of 3–4 in 2 l of YPD medium. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000g for 5 min, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at −80° C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of the lysis buffer (10% glycerol, 0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 20 mM creatine phosphate, creatine phosphokinase (20 μg/ml), 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). Cells were disrupted using a FastPrep-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals) at the speed setting of 4.5, at 20 s/cycle for 10 cycles. After removal of glass beads, extract was cleared by centrifugation at 11,2000g for 30 min, followed by incubation with 0.2 ml of anti-flag M2 agarose beads (Sigma) for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed twice in 10 ml of storage buffer (10% glycerol, 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), then once with 5 ml of the same buffer containing also 0.2% Triton X-100, and thereafter again once with 5 ml of the storage buffer. The proteasomes were eluted with the triple-flag peptide (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma) in storage buffer and dialyzed against 1 l of storage buffer overnight at 4° C. Polyubiquitylated Leu-DHFRha, the N-end rule substrate for degradation assay, was prepared by incubating the above in vitro ubiquitylation assay at 30° C for 18 h. The reaction mixture was prepared by adding 1 μl of the purified 26S proteasome (~500 nM; its final concentration was ~50 nM) to 8 μl of reaction buffer (2 mM ATP, 10% glycerol, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), and thereafter adding 1 μl of polyubiquitylated Leu-DHFRha (1.25 μM; its final concentration was 125 nM). The reaction was performed at 30°C for 10 and 20 min, followed by the addition of 3 μl of the 4xSDS-sample buffer, heating the samples at 95°C for 5 min, and carrying out SDS-4-12% NuPAGE, following by immunoblotting with anti-ha.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank an anonymous reviewer for insightful comments that contributed to improvements of the paper. We also thank S. Jentsch and A. Toh-e for strains and plasmids. We are grateful to the present and former members of the Varshavsky laboratory, particularly to J. Sheng and K. Piatkov, for gifts of plasmids and strains, and to O. Batygin for technical assistance. This work was supported by the NIH grants GM031530, DK039520 and GM085371 (A.V.), and also by grants from the March of Dimes Foundation and the Caltech-City of Hope Biomedical Initiative (A.V.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.-S.H, A.S., D.A. and A.V. designed experiments, C.-S.H., and A.S. performed the experiments, C.-S.H, A.S. and A.V. wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Bachmair A, Finley D, Varshavsky A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 1986;234:179–186. doi: 10.1126/science.3018930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varshavsky A. The N-end rule: functions, mysteries, uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93 :12142–12149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varshavsky A. Discovery of cellular regulation by protein degradation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34469–34489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.X800009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Diversity of degradation signals in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:679–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner GC, Du F, Varshavsky A. Peptides accelerate their uptake by activating a ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic pathway. Nature. 2000;405:579–583. doi: 10.1038/35014629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao H, Uhlmann F, Nasmyth K, Varshavsky A. Degradation of a cohesin subunit by the N-end rule pathway is essential for chromosome stability. Nature. 2001;410:955–960. doi: 10.1038/35073627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu RG, et al. The N-end rule pathway as a nitric oxide sensor controlling the levels of multiple regulators. Nature. 2005;437:981–986. doi: 10.1038/nature04027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tasaki T, Kwon YT. The mammalian N-end rule pathway: new insights into its components and physiological roles. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mogk A, Schmidt R, Bukau B. The N-end rule pathway of regulated proteolysis: prokaryotic and eukaryotic strategies. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu R-G, Wang H, Xia Z, Varshavsky A. The N-end rule pathway is a sensor of heme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:76–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710568105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang C-S, Varshavsky A. Regulation of peptide import through phosphorylation of Ubr1, the ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19188–19193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808891105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang C-S, Shemorry A, Varshavsky A. Two proteolytic pathways regulate DNA repair by co-targeting the Mgt1 alkyguanine transferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2142–2147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812316106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt R, Zahn R, Bukau B, Mogk A. ClpS is the recognition component for Escherichia coli substrates of the N-end rule degradation pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:506–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Román-Hernández G, Grant RA, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Molecular basis of substrate selection by the N-end rule adaptor protein ClpS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8888–8893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903614106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Piatkov KI, Brower CS, Varshavsky A. Glutamine-specific N-terminal amidase, a component of the N-end rule pathway. Mol Cell. 2009;34:686–695. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brower CS, Varshavsky A. Ablation of arginylation in the mouse N-end rule pathway: loss of fat, higher metabolic rate, damaged spermatogenesis, and neurological perturbations. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tasaki T, et al. The substrate recognition domains of the N-end rule pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1884–1895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803641200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang CS, Shemorry A, Varshavsky A. N-terminal acetylation of cellular proteins creates specific degradation signals. Science. 2010;327:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1183147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu F, Walters KJ. Multitasking with ubiquitin through multivalent interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochstrasser M. Origin and function of ubiquitin-like proteins. Nature. 2009;458:422–429. doi: 10.1038/nature07958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dye BT, Schulman BA. Structural mechanisms underlying posttranslational modification by ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2007;36:131–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du F, Navarro-Garcia F, Xia Z, Tasaki T, Varshavsky A. Pairs of dipeptides synergistically activate the binding of substrate by ubiquitin ligase through dissociation of its autoinhibitory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14110–14115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172527399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia Z, et al. Substrate-binding sites of UBR1, the ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24011–24028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802583200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi WS, et al. Structural basis for the recognition of N-end rule substrates by the UBR box of ubiquitin ligases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1175–1182. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matta-Camacho E, Kozlov G, Li FF, Gehring K. Structural basis of substrate recognition and specificity in the N-end rule pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1182–1188. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sriram SM, Kwon YT. The structural basis of N-end rule recognition. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1164–1165. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1010-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia Z, Turner GC, Hwang C-S, Byrd C, Varshavsky A. Amino acids induce peptide uptake via accelerated degradation of CUP9, the transcriptional repressor of the PTR2 peptide transporter. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28958–28968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803980200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heck JW, Cheung SK, Hampton RY. Cytoplasmic protein quality control degradation mediated by parallel actions of the E3 ubiquitin ligases Ubr1 and San1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1106–1111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910591107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisele F, Wolf DH. Degradation of misfolded proteins in the cytoplasm by the ubiquitin ligase Ubr1. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:4143–4146. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasad R, Kawaguchi S, Ng DTW. A nucleus-based quality control mechanism for cytosolic proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2117–2127. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nillegoda NB, et al. Ubr1 and Ubr2 function in a quality control pathway for degradation of unfolded cytosolic proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2102–2116. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwon YT, et al. An essential role of N-terminal arginylation in cardiovascular development. Science. 2002;297:96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.1069531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai H, Kauffman S, Naider F, Becker JM. Genomewide screen reveals a wide regulatory network for di/tripeptide utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2006;172:1459–1476. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.053041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graciet E, Wellmer F. The plant N-end rule pathway: structure and functions. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurosaka S, et al. Arginylation-dependent neural crest cell migration is essential for mouse development. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karakozova M, et al. Arginylation of beta-actin regulates actin cytoskeleton and cell motility. Science. 2006;313:192–196. doi: 10.1126/science.1129344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caprio MA, Sambrooks CL, Durand ES, Hallak M. The arginylation-dependent association of calreticulin with stress granules is regulated by calcium. Biochem J. 2010;429:63–72. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson ES, Ma PC, Ota IM, Varshavsky A. A proteolytic pathway that recognizes ubiquitin as a degradation signal. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17442–17456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Autoregulation of an E2 enzyme by ubiquitin-chain assembly on its catalytic residue. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:422–427. doi: 10.1038/ncb1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ju D, Wang X, Xu H, Xie Y. The armadillo repeats of the Ufd4 ubiquitin ligase recognize ubiquitin-fusion proteins. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie Y, Varshavsky A. Physical association of ubiquitin ligases and the 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2497–2502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060025497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Y, Varshavsky A. UFD4 lacking the proteasome-binding region catalyses ubiquitination but is impaired in proteolysis. Nature Cell Biol. 2002;4:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/ncb889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kee Y, Huibregtse JM. Regulation of catalytic activities of HECT ubiquitin ligases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson ES, Bartel BW, Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin as a degradation signal. EMBO J. 1992;11:497–505. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koegl M, et al. A novel ubiquitination factor, E4, is involved in multiubiquitin chain assembly. Cell. 1999;96:635–644. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu P, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals the function of unconventional ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation. Cell. 2009;137:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hochstrasser M. Lingering mysteries of ubiquitin-chain assembly. Cell. 2006;124:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chau V, et al. A multiubiquitin chain is confined to specific lysine in a targeted short-lived protein. Science. 1989;243:1576–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodrigo-Brenni MC, Morgan DO. Sequential E2s drive polyubiquitin chain assembly on APC targets. Cell. 2007;130:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoppe T. Multiubiquitylation by E4 enzymes: 'one size' doesn't fit all. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott DC, et al. A dual mechanism for Rub1 ligation to Cdc53. Mol Cell. 2010;39:784–796. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnsson N, Varshavsky A. Split ubiquitin as a sensor of protein interactions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10340–10344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Möckli N, et al. Yeast split-ubiquitin-based cytosolic screening system to detect interactions between transcriptionally active proteins. BioTechniques. 2007;42:725–729. doi: 10.2144/000112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin fusion technique and related methods. Meth Enzymol. 2005;399:777–799. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catanzariti AM, Soboleva TA, Jans DA, Board PG, Baker RT. An efficient system for high-level expression and easy purification of authentic recombinant proteins. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1331–1339. doi: 10.1110/ps.04618904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saeki Y, Isono E, Toh EA. Preparation of ubiquitinated substrates by the PY motif-insertion method for monitoring 26S proteasome activity. Meth Enzymol. 2005;399:215–227. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turner GC, Varshavsky A. Detecting and measuring cotranslational protein degradation in vivo. Science. 2000;289:2117–2120. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu C, et al. Ubiquitin chain elongation enzyme Ufd2 regulates a subset of Doa10 substrates. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10265–10272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tu D, Li W, Ye Y, Brunger AT. Structure and function of the yeast U-box-containing ubiquitin ligase Ufd2p. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15599–15606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701369104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Courbard JR, et al. Interaction between two ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligases of different classes, CBLC and AIP4/ITCH. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45267–45275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen C, et al. The WW domain-containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 upregulates ErbB2 and EGFR through RING finger protein 11. Oncogene. 2008;27:6845–6855. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Magnifico A, et al. WW domain HECT E3s target Cbl RING finger E3s for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43169–43177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zaaroor-Regev D, et al. Regulation of the polycomb protein Ring1B by self-ubiquitination or by E6-AP may have implications to the pathogenesis of Angelman syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6788–6793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003108107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Varshavsky A. Spalog and sequelog: neutral terms for spatial and sequence similarity. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R181–R183. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park Y, Yoon SK, Yoon JB. The HECT domain of TRIP12 ubiquitinates substrates of the ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1540–1549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gardner RG, Nelson ZW, Gottschling DE. Degradation-mediated protein quality control in the nucleus. Cell. 2005;120:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Longtine MS, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ausubel FM, et al. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kushnirov VV. Rapid and reliable protein extraction from yeast. Yeast. 2000;16:857–860. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000630)16:9<857::AID-YEA561>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.