Abstract

Collagens are the most abundant proteins in mammals. The collagen family comprises 28 members that contain at least one triple-helical domain. Collagens are deposited in the extracellular matrix where most of them form supramolecular assemblies. Four collagens are type II membrane proteins that also exist in a soluble form released from the cell surface by shedding. Collagens play structural roles and contribute to mechanical properties, organization, and shape of tissues. They interact with cells via several receptor families and regulate their proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Some collagens have a restricted tissue distribution and hence specific biological functions.

Collagens form supramolecular assemblies in the extracellular matrix that help organize and shape tissues. They also interact with cell surface receptors to regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration.

Collagens are the most abundant proteins in mammals (∼30% of total protein mass). Since the discovery of collagen II by Miller and Matukas (1969), 26 new collagen types have been found, and their discovery has been accelerated by molecular biology and gene cloning. Several reviews on the collagen family have been published (Miller and Gay 1982; van der Rest and Garrone 1991; Kadler 1995; Ricard-Blum et al. 2000, 2005; Myllyharju and Kivirikko 2004; Ricard-Blum and Ruggiero 2005; Kadler et al. 2007; Gordon and Hahn 2010) and even if the question “What is collagen, what is not?” (Gay and Miller 1983) may still be valid, numerous answers have been provided giving new insights into the structure and the biological roles of collagens.

THE COLLAGEN SUPERFAMILY

The collagen superfamily comprises 28 members numbered with Roman numerals in vertebrates (I–XXVIII) (Table 1). A novel epidermal collagen has been called collagen XXIX (Söderhäll et al. 2007), but the COL29A1 gene was shown to be identical to the COL6A5 gene, and the α1(XXIX) chain corresponds to the α5(VI) chain (Gara et al. 2008). The common structural feature of collagens is the presence of a triple helix that can range from most of their structure (96% for collagen I) to less than 10% (collagen XII). As described in the following discussion, the diversity of the collagen family is further increased by the existence of several α chains, several molecular isoforms and supramolecular structures for a single collagen type, and the use of alternative promoters and alternative splicing.

Table 1.

The collagen family.

| Collagen type | α Chains | Molecular species |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen I | α1(I), α2(I) | [α1(I)]2, α2(I) [α1(I)]3 |

| Collagen II | α1(II) | [α1(II)]3 |

| Collagen III | α1(III) | [α1(III)]3 |

| Collagen IV | α1(IV), α2(IV), α3(IV), α4(IV), α5(IV), α6(IV) |

[α1(IV)]2, α2(IV) α3(IV), α4(IV), α5(IV) [α5(IV)]2, α6(IV) |

| Collagen V | α1(V), α2(V), α3(V), α4(V)a | [α1(V)]2, α2(V) [α1(V)]3 [α1(V)]2α4(V) α1(XI)α1(V)α3(XI) |

| Collagen VI | α1(VI), α2(VI), α3(VI), α4(VI)b, α5(VI)c, α6(V) | |

| Collagen VII | α1(VII) | [α1(VII)]3 |

| Collagen VIII | α1(VIII) | [α1(VIII)]2, α2(VIII) α1(VIII), [α2(VIII)]2 [α1(VIII)]3 [α2(VIII)]3 |

| Collagen IXe | α1(IX), α2(IX), α3(IX) | [α1(IX), α2(IX), α3(IX)] |

| Collagen X | α1(X) | [α1(X)]3 |

| Collagen XI | α1(XI), α2(XI), α3(XI)d | α1(XI)α2(XI)α3(XI) α1(XI)α1(V)α3(XI) |

| Collagen XIIe | α1(XII) | [α1(XII)]3 |

| Collagen XIII | α1(XIII) | [α1(XIII)]3 |

| Collagen XIVe | α1(XIV) | [α1(XIV)]3 |

| Collagen XV | α1(XV) | [α1(XV)]3 |

| Collagen XVIe | α1(XVI) | [α1(XVI)]3 |

| Collagen XVII | α1(XVII) | [α1(XVII)]3 |

| Collagen XVIII | α1(XVIII) | [α1(XVIII)]3 |

| Collagen XIXe | α1(XIX) | [α1(XIX)]3 |

| Collagen XXe | α1(XX) | [α1(XX)]3 |

| Collagen XXIe | α1(XXI) | [α1(XXI)]3 |

| Collagen XXIIe | α1(XXII) | [α1(XXII)]3 |

| Collagen XXIII | α1(XXIII) | [α1(XXIII)]3 |

| Collagen XXIV | α1(XXIV) | [α1(XXIV)]3 |

| Collagen XXV | α1(XXV) | [α1(XXV)]3 |

| Collagen XXVI | α1(XXVI) | [α1(XXVI)]3 |

| Collagen XXVII | α1(XXVII) | [α1(XXVII)]3 |

| Collagen XXVIII | α1(XXVIII) | [α1(XXVIII)]3 |

Individual α chains, molecular species, and supramolecular assemblies of collagen types.

aThe α4(V) chain is solely synthesized by Schwann cells.

bThe α4(VI) chain does not exist in humans.

cThe α5(VI) has been designated as α1(XXIX).

dThe α3(XI) chain has the same sequence as the α1(II) chain but differs in its posttranslational processing and cross-linking.

eFACIT, Fibril-Associated Collagens with Interrupted Triple helices.

The criteria to name a protein collagen are not well defined and other proteins containing one triple-helical domain (Table 2) are not numbered with a Roman numeral so far and do not belong to the collagen family sensu stricto. Some of them, containing a recognition domain contiguous with a collagen-like triple-helical domain, are called soluble defense collagens (Fraser and Tenner 2008), and gliomedin is recognized as a membrane collagen (Maertens et al. 2007).

Table 2.

Proteins containing a collagen-like domain.

| Protein name | Domain composition | Cellular component |

|---|---|---|

| Complement C1q (subcomponent subunits A, B, C) | Collagen-like domain C1q domain |

Secreted |

| Adiponectin | Collagen-like domain C1q domain |

Secreted |

| Mannose-binding protein C | Collagen-like domain C-type lectin Cystein-rich domain |

Secreted |

| Ficolins 1, 2, and 3 | Collagen-like domain Fibrinogen-like domain |

Secreted |

| Acetylcholinesterase collagenic tail peptide (collagen Q) | Collagen-like domain Proline-rich attachment domain domain |

Secreted |

| Pulmonary surfactant-associated proteins A1 and A2 | Collagen-like domain C-type lectin |

Secreted Extracellular matrix |

| Pulmonary surfactant-associated protein D | Collagen-like domain C-type lectin |

Secreted Extracellular matrix |

| Ectodysplasin A | Collagen-like domain Signal-anchor for type II membrane protein Cytoplasmic |

Single-pass type II membrane protein |

| Macrophage receptor (MARCO) | SRCR Collagen-like domain Signal-anchor for type II membrane protein Cytoplasmic |

Single-pass type II membrane protein |

| Gliomedin | Pro-rich domain Olfactomedin-like domain Collagen-like domain Signal-anchor for type II membrane protein |

Single-pass type II membrane protein |

| EMI domain-containing protein 1 | EMI domain Collagen-like domain |

Secreted Extracellular matrix |

| Emilin-1 | EMI domain Collagen-like domain C1q domain |

Secreted Extracellular matrix |

| Emilin-2 | EMI domain Collagen-like domain C1q domain |

Secreted Extracellular matrix |

The names are those indicated for human proteins in the UniProtKB database (http://www.uniprot.org/, release 2010_08 - Jul 13, 2010).

Beyond Collagen Types: Increased Molecular Diversity of the Collagen Family

Collagens consist of three polypeptide chains, called α chains, numbered with Arabic numerals. Beyond the existence of 28 collagen types, further diversity occurs in the collagen family because of the existence of several molecular isoforms for the same collagen type (e.g., collagens IV and VI) and of hybrid isoforms comprised of α chains belonging to two different collagen types (type V/XI molecules) (Table 1). Indeed collagen XI is comprised of three α chains assembled into a heterotrimer (Table 1), but the α(XI) chain forms type V/XI hybrid collagen molecules by assembling with the α1(V) chain in vitreous (Mayne et al. 1993) and cartilage (Wu et al. 2009) (Table 1). There is an increase in α1(V) and a decrease in α2(XI) during postnatal maturation of cartilage (Wu et al. 2009).

The use of two alternative promoters gives different forms of α1(IX) and α(XVIII) chains, and alternative splicing contributes to the existence of several isoforms of α1(II), α2(VI), α3(VI), α1(VII), α1(XII), α1(XIII), α1(XIV), α1(XIX), α1(XXV), and α1(XXVIII) chains. Splicing events are sometimes specific to a tissue and/or a developmental stage, and splicing variants modulate collagen functions. Several collagens (IX, XII, XIV, XV, XVIII) carry glycosaminoglycan chains (chondroitin sulfate and/or heparan sulfate chains) and are considered also as proteoglycans.

Additional levels of functional diversity are due (1) to the proteolytic cleavage of several collagen types to release bioactive fragments displaying biological activities of their own, and (2) to the exposure of functional cryptic sites because of conformational changes induced in collagens by interactions with extracellular proteins or glycosaminoglycans, multimerization, denaturation, or mechanical forces (Ricard-Blum and Ballut 2011). Membrane collagens exist in two different forms, a transmembrane form and a soluble one, released by shedding, that regulates cell behavior (Franzke et al. 2005).

THE STRUCTURAL ORGANIZATION OF COLLAGENS

A Common Structural Motif: The Triple Helix

Collagen α chains vary in size from 662 up to 3152 amino acids for the human α1(X) and α3(VI) chains respectively (Ricard-Blum et al. 2000; Gordon and Hahn 2010). The three α chains can be either identical to form homotrimers (e.g., collagen II) (Table 1) or different to form heterotrimers (e.g., collagen IX) (Table 1). The three α chains of fibril-forming collagens are three left-handed polyproline II helices twisted in a right-handed triple helix with a one-residue stagger between adjacent α chains. The triple helix is stabilized by the presence of glycine as every third residue, a high content of proline and hydroxyproline, interchain hydrogen bonds, and electrostatic interactions (Persikov et al. 2005), involving lysine and aspartate (Fallas et al. 2009). The triple-helical sequences are comprised of Gly-X-Y repeats, X and Y being frequently proline and 4-hydroxyproline, respectively. Location of 3-hydroxyproline residues, which could participate in the formation of supramolecular assemblies, have been identified in collagens I, II, III, and V/XI (Weiss et al. 2010). The triple helix is rod-shaped, but it can be flexible because of the presence of Gly-X-Y imperfections (one to three amino acid residues) and interruptions (up to 21–26 interruptions in the collagen IV chains, Khoshnoodi et al. 2008). These interruptions are associated at the molecular level with local regions of considerable plasticity and flexibility and molecular recognition (Bella et al. 2006).

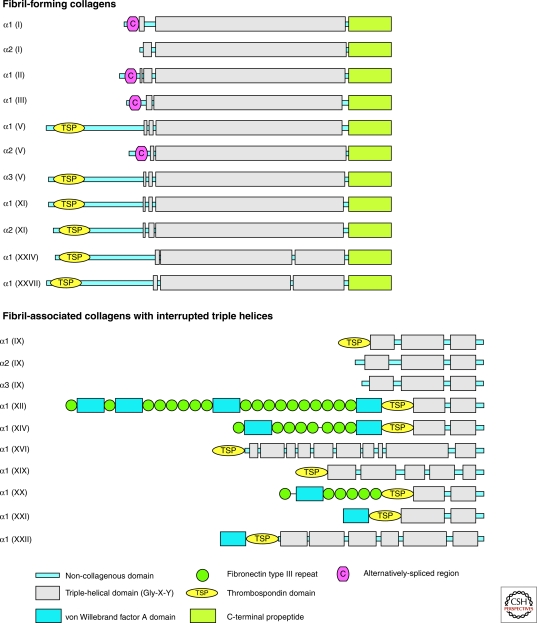

Collagens are Multidomain Proteins

Fibrillar collagens contain one major triple-helical domain. In contrast, collagens belonging to the fibril-associated collagens with interrupted triple-helices (FACIT), the multiplexins and the membrane collagen subfamilies contain several triple-helical domains Fig. 1). The discovery of collagen IX, the first FACIT, was a major breakthrough in the collagen field showing that triple-helical, collagenous domains could be interspersed among non-collagenous (NC) domains (Shaw and Olsen 1991) and that collagens were multidomain proteins (Fig. 1). The non-collagenous domains participate in structural assembly and confer biological activities to collagens. They are frequently repeated within the same collagen molecule and are also found in other extracellular proteins. Fibronectin III, Kunitz, thrombospondin-1, and von Willebrand domains are the most abundant in collagens (Fig. 1). The von Willebrand domain that participates in protein-protein interactions is found in collagens VI, VII, XII, XIV, XX, XXI, XXII, and XXVIII (Fig. 1). The role of the Kunitz domain that is cleaved during the maturation of collagens VI or VII is not yet elucidated. Collagen XXVIII closely resembles collagen VI by having a triple-helical domain flanked by von Willebrand domains at the amino-terminus and a Kunitz domain at the carboxy-terminus, but its tissue distribution is more restricted than collagen VI (Veit et al. 2006). The four membrane collagens (Table 1) are single-pass type II membrane proteins comprising a cytoplasmic domain, a transmembrane domain, and several triple-helical domains located in the extracellular matrix ((Franzke et al. 2005).

Figure 1.

Structural organization of collagens. Domain composition and supramolecular assemblies of collagens. COL, Collagenous, triple-helical, domains; NC, Non-collagenous, nontriple-helical, domains. They are numbered from the carboxy- to the amino-terminus, except for collagen VII. (Figure continued on following page.)

The Trimerization Domains

Folding of the triple helix requires trimerization domains that ensure the proper selection and alignment of collagen α chains, and allows the triple helix to fold in a zipper-like fashion (Khosnoodi et al. 2006). The formation of the triple-helix is initiated from the carboxyl terminus for fibrillar collagens and from the amino terminus for membrane collagens (Khosnoodi et al. 2006). The trimerization domains of collagens IV, VIII, and X that assemble into networks are their non-collagenous carboxy-terminal domains. The carboxy-terminal trimeric NC1 domains of the homotrimers [α1(VIII)]3 and [α1(X)]3 are comprised of a ten-stranded β sandwich, and expose three strips of aromatic residues that seem to participate in their supramolecular assembly (Bogin et al. 2002, Kvansakul et al. 2003) (PDB ID: 1O91). The trimerization domain of collagen XVIII, a member of the multiplexin subfamily, spans the first 54 residues of the non-collagenous carboxy-terminal (NC1) domain. Each chain has four β-strands, one α-helix, and a short 310 helix (Boudko et al. 2009) (PDB ID: 3HON and 3HSH). This domain is smaller than the trimerization domain of fibrillar collagens (∼250 residues) and shows high trimerization potential at picomolar concentrations (Boudko et al. 2009). The trimerization domain of collagen XV, the other multiplexin, has been modeled by homology. The trimerization of collagens IX and XIX (FACITs) is governed by their NC2 domain (Fig. 1), the second non-collagenous domain starting from the carboxyl terminus (Boudko et al. 2008, Boudko et al. 2010). The C1 subdomain located at the carboxyl terminus of α1, α2 and α3 chains of collagen VI is sufficient to promote chain recognition and trimeric assembly (Khoshnoodi et al. 2006).

SUPRAMOLECULAR ASSEMBLIES OF COLLAGENS

When visualized by electron microscopy after rotary shadowing, collagen molecules are visualized as rods varying in length from approximately 75 nm for collagen XII to 425 nm for collagen VII (Ricard-Blum et al. 2000). The molecular structure of collagen XV extracted from tissue has an unusual shape, most molecules being found in a knot/figure-of-eight/pretzel configuration (Myers et al. 2007), although recombinant collagen XV appears elongated in rotary shadowing (Hurskainen et al. 2010). Kinks caused by the presence of non-collagenous domains are observed in electron microscopy of nonfibrillar collagen preparations. Non-collagenous domains can also be characterized by electron microscopy after rotary shadowing (e.g., the trimeric carboxy-terminal NC1 domain of collagen XVIII, Sasaki et al. [1998]).

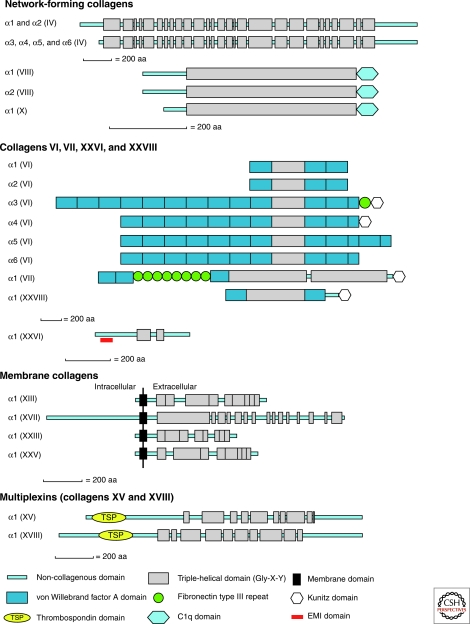

Fibril-Forming Collagens

Collagens can be subdivided into subfamilies based on their supramolecular assemblies: fibrils, beaded filaments, anchoring fibrils, and networks (Fig. 2). Most collagen fibrils are comprised of several collagen types and are called heterotypic. Collagen fibrils are made of collagens II, XI, and IX or of collagens II and III (Wu et al. 2010) in cartilage, of collagens I and III in skin, and of collagens I and V in cornea (Bruckner et al. 2010). Furthermore, collagen fibrils can be considered as macromolecular alloys of collagens and non-collagenous proteins or proteoglycans. Indeed, small leucine-rich proteoglycans regulate fibrillogenesis, as do collagens V and XIV (Wenstrup et al. 2004; Ansorge et al. 2009), and could also influence collagen cross-linking (Kalamajski and Oldberg 2010). Fibronectin and integrins could act as organizers, and collagens V and XI as nucleators for fibrillogenesis of collagens I and II (Kadler et al. 2008). Collagen fibrillogenesis has been extensively studied in tendons, but the site of the initial steps of fibrillogenesis is not clearly defined so far. They may take place in extracellular compartments where fibril intermediates are assembled and mature fibrils grow through a fusion process of intermediates (Zhang et al. 2005), or they may occur intracellularly, in Golgi-to-membrane carriers containing 28-nm-diameter fibrils that are targeted to plasma membrane protrusions called fibripositors (Canty et al. 2004). The two models have been discussed (Banos et al. 2008).

Figure 2.

Supramolecular assemblies formed by collagens.

Collagen fibrils show a banding pattern with a periodicity (D) of 64–67 nm (Brückner 2010), and collagen molecules are D-staggered within the fibrils. Collagen fibrils range in diameter from approximately 15 nm up to 500 nm or more depending on the tissue (Kadler et al. 2007; Brückner 2010). Collagen XXVII forms thin nonstriated fibrils (10 nm in diameter) that are distinct from the classical collagen fibrils (Plumb et al. 2007). The microfibrillar structure of collagen I fibrils has been investigated in situ by X-ray diffraction of rat tail tendons (Orgel et al. 2006). Collagen I forms supertwisted microfibrils of five molecules that interdigitate with neighboring microfibrils, leading to the quasi-hexagonal packing of collagen molecules (Orgel et al. 2006). In contrast, cartilage fibrils are made of a core of four microfibrils (two of collagen II and two of collagen XI) surrounded by a ring of ten microfibrils, each microfibril containing five collagen molecules in cross-section (Holmes and Kadler 2006).

Fibril-Associated Collagens

The FACITs do not form fibrils by themselves, but they are associated to the surface of collagen fibrils. Collagen IX is covalently linked to the surface of cartilage collagen fibrils mostly composed of collagen II (Olsen 1997), and collagens XII and XIV are associated to collagen I-containing fibrils. Collagen XV is associated with collagen fibrils in very close proximity to the basement membrane and forms a bridge linking large, banded fibrils, likely fibrils containing collagens I and III (Amenta et al. 2005).

Network-Forming Collagens

Collagen IV forms a network in which four molecules assemble via their amino-terminal 7S domain to form tetramers, and two molecules assemble via their carboxy-terminal NC1 domain to form NC1 dimers. Because the NC1 domains are trimeric, the NC1 dimer is a hexamer. The three-dimensional structure of the hexameric form of the NC1 domain that plays a major role in collagen IV assembly and in the stabilization of the collagen [α1(IV)]2α(IV) network has been determined (Sundaramoorthy et al. [2002], PDB ID: 1M3D, Than et al. [2002], PDB ID: 1LI1). It was hypothesized that collagen IV was stabilized via a covalent Met-Lys cross-link (Than et al. 2002), but studies of a crystal structure of the NC1 domain (PDB ID: 1T60, 1T61) at a higher resolution failed to confirm its existence (Vanacore et al. 2004). A combination of trypsin digestion and mass spectrometry analysis has led to the identification of a S-hydroxylysyl-methionine connecting Met93 and Hyl211 as the covalent cross-link that stabilizes the NC1 hexamer of the [α1(IV)]2α2(IV) network (Vanacore et al. 2005). Other collagen IV networks result from the assembly of the two molecular isoforms [α1(IV)]2α2(IV) and [α5(IV)]2α6(IV), and from the assembly of α3(IV)α4(IV)α5(IV) with itself (Borza et al. 2001). Collagens VIII and X form hexagonal networks in Descemet’s membrane and in hypertrophic cartilage, respectively. Collagen VI forms beaded filaments and collagen VII assembles into anchoring fibrils connecting the epidermis to the dermis (Ricard-Blum et al. 2000; Gordon and Hahn 2010; Fig. 2).

Some collagens participate in distinct molecular assemblies. Collagen XVI is a component of microfibrils containing fibrillin-1 in skin, whereas it is incorporated into thin, weakly banded fibrils containing collagens II and XI in cartilage (Kassner et al. 2003). Collagen XII, a fibril-associated collagen, has been reported to be associated with basement membranes in zebra fish (Bader et al. 2009). Supramolecular assemblies of several collagens are able to interact as shown for the anchoring fibrils that are tightly attached to striated collagen fibrils (Villone et al. 2008).

COLLAGEN BIOSYNTHESIS

Collagen biosynthesis has been extensively studied for fibril-forming collagens that are synthesized as procollagen molecules comprised of an amino-terminal propeptide followed by a short, nonhelical, N-telopeptide, a central triple helix, a C-telopeptide and a carboxy-terminal propeptide. Individual proα chains are submitted to numerous posttranslational modifications (hydroxylation of proline and lysine residues, glycosylation of lysine and hydroxylysine residues, sulfation of tyrosine residues, Myllyharju and Kivirikko 2004) that are stopped by the formation of the triple helix. The heat shock protein 47 (HSP47) binds to procollagen in the endoplasmic reticulum and is a specific molecular chaperone of procollagen (Sauk et al. 2005). The stabilization of procollagen triple helix at body temperature requires the binding of more than 20 HSP47 molecules per triple helix (Makareeva and Leikin 2007). It has been recently suggested that intracellular Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (SPARC) might be a collagen chaperone because it binds to the triple-helical domain of procollagens and its absence leads to defects in collagen deposition in tissues (Martinek et al. 2007).

Both propeptides of procollagens are cleaved during the maturation process (Greenspan 2005). The N-propeptide is cleaved by procollagen N-proteinases belonging to the A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) family, except the N-propeptide of the proα1(V) chain that is cleaved by the procollagen C-proteinase also termed Bone Morphogenetic Protein-1 (BMP-1) (Hopkins et al. 2007). BMP-1 cleaves the carboxy-terminal propeptide of procollagens, except the carboxy-terminal propeptide of the proα1(V) chain, that is processed by furin. The telopeptides contain the sites where cross-linking occurs. This process is initiated by the oxidative deamination of lysyl and hydroxylsyl residues catalyzed by the enzymes of the lysyl oxidase family (Mäki 2009).

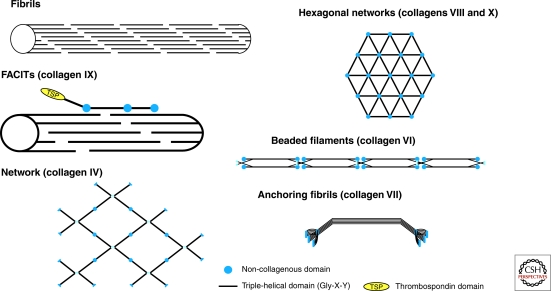

COVALENT CROSS-LINKING OF COLLAGENS

Collagen is considered as an elastic protein with a resilience of ∼90%. Collagen fibrils are thus able to deform reversibly and their mechanical properties can be investigated by force spectroscopy (Gutsmann et al. 2004). The mechanical properties of fibril-forming collagens I, II, III, V, and XI are dependent on covalent cross-links including (1) Disulfide bonds (in collagens III, IV, VI, VII, and XVI); (2) the Nε(γ-glutamyl)lysine isopeptide, the formation of which is catalyzed by transglutaminase-2 in collagens I, III, V/XI, and VII (Esposito and Caputo 2005); (3) reducible and mature cross-links produced via the lysyl oxidase pathway; and (4) advanced glycation end products (Avery and Bailey 2006). Furthermore, a hydroxylysine-methionine cross-link involving a sulfilimine (-S=N-) bond has been identified in collagen IV (Vanacore et al. 2009).

Lysyl-mediated cross-linking involves lysine, hydroxylysine, and histidine residues, and occurs at the intramolecular and intermolecular levels between collagen molecules belonging either to the same type or to different types (I/II, I/III, I/V, II/III, II/IX, II/XI, and V/XI) (Eyre et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2009, 2010). Cross-linking is tissue-specific rather than collagen-specific. Reducible, bifunctional, cross-links (aldimines and keto-imines) are formed in newly synthesized collagens, and they spontaneously mature into nonreducible trifunctional cross-links, pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline in bone and cartilage, pyrrole cross-links in bone, and histidinohydroxylysinonorleucine in skin (Eyre and Wu 2005; Robins 2007) (Fig. 3). Another mature cross-link, an arginyl ketoimine adduct called arginoline because of the contribution of one arginine residue, has been identified in cartilage (Eyre et al. 2010) (Fig. 3). Cross-link maturation provides added resistance to shear stress. Pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline are used as urinary markers of bone resorption in patients with bone diseases such as osteoporosis (Saito and Marumo 2010).

Figure 3.

Collagen cross-links. Lysyl-mediated mature cross-links: argoline, deoxypyridinoline, pyridinoline, and histidinohydroxylysinonorleucine. Advanced glycation endproducts: glucosepane and pentosidine.

Collagens are long-lived proteins that are modified by glycation (Avery and Bailey 2006). Glycation increases with age and several advanced glycation endproducts act as cross-links that contribute to the progressive insolubilization and to the increased stiffness of collagens in aged tissues. Two lysine-arginine cross-links, pentosidine (a fluorescent product formed from ribose), and glucosepane (a nonfluorescent product formed from glucose) have been identified in collagens. Glucosepane, the most abundant cross-link in senescent skin collagen, is able to cross-link one in five collagen molecules in the skin of the elderly (Sjöberg and Bulterijs 2009).

COLLAGEN DEGRADATION

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent endopeptidases belonging to the metzincin superfamily. They participate in physiological (development and tissue repair) and pathological (tumorigenesis and metastasis) processes. Fibril-forming collagens I, II, and III are cleaved by MMP-1 (interstitial collagenase), MMP-8 (neutrophil collagenase), MMP-13 (collagenase 3) that generate three-quarter and one-quarter sized fragments, and by membrane-anchored MMP-14. MMP-2 is also able to cleave collagen I (Klein and Bischoff 2010). Collagen II is a preferential substrate of MMP-13, whereas collagens I and III are preferentially cleaved by MMP-1 and MMP-8 (Klein and Bischoff 2010). Denatured collagens and collagen IV are degraded by MMP-2 and MMP-9 (also known as 72-kDa and 92-kDa gelatinases respectively). In contrast to the [α1 (I)]2α2(I) heterotrimer of collagen I, the [α2 (I)]3 homotrimer is not degraded by mammalian collagenases. This is because of resistance of the homotrimer to local triple helix unwinding by MMP-1 because it has higher triple helix stability near the MMP cleavage site (Han et al. 2010). MMPs also contribute to the release of bioactive fragments or matricryptins such as endostatin and tumstatin from full-length collagens (Ricard-Blum and Ballut 2011). Another group of enzymes, collectively called sheddases (Murphy 2009) releases the ectodomain of membrane collagens as soluble forms.

COLLAGEN RECEPTORS

Collagens are deposited in the extracellular matrix, but they participate in cell-matrix interactions via several receptor families (Heino et al. 2007, 2009; Humphries et al. 2006; Leitinger and Hohenester 2007). They are ligands of integrins, cell-adhesion receptors that lack intrinsic kinase activities. Collagens bind to integrins containing a β1 subunit combined with one of the four subunits containing an αA domain (α1, α2, α10, and α11) via GFOGER-like sequences, O being hydroxyproline (Humphries et al. 2006; Heino et al. 2007). There are other recognition sequences in collagens such as KGD in the ectodomain of collagen XVII, which is recognized by α5β1 and αvβ1 integrins but not by the “classical” collagen receptors (Heino et al. 2007). Several bioactive fragments resulting from the proteolytic cleavage of collagens are ligands of αvβ3, αvβ5, α3β1, and α5β1 integrins (Ricard-Blum and Ballut 2011).

Collagens I–III are also ligands of the dimeric discoidin receptors DDR1 and DDR2 that possess tyrosine kinase activities (Leitinger and Hohenester 2007). The major DDR2-binding site in collagens I–III is a GVMGFO motif (Heino et al. 2009). The crystal structure of a triple-helical collagen peptide bound to the discoidin domain (DS) of DDR2 has provided insight into the mechanism of DDR activation that may involve structural changes of DDR2 surface loops induced by collagen binding (Carafoli et al. 2009) (PDB ID: 2WUH). The activation may result from the simultaneous binding of both DS domains in the dimer to a single collagen triple helix, or DS domains may bind collagen independently (Carafoli et al. 2009). The soluble extracellular domains of DDR1 and DDR2 regulate collagen deposition in the extracellular matrix by inhibiting fibrillogenesis (Flynn et al. 2010). DDR2 affects mechanical properties of collagen I fibers by reducing their persistence length and their Young’s modulus (Sivakumar and Agarwal 2010).

Collagens bind to glycoprotein VI (GPVI), a member of the paired immunoglobulin-like receptor family, on platelets (Heino et al. 2007), and to the inhibitory leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 (LAIR-1, Lebbink et al. 2006). Both receptors recognize the GPO motif in collagens. Ligands of LAIR-1 are fibrillar collagens I, II, and III, and membrane collagens XIII, XVII, and XXIII. Collagens I and III are functional ligands of LAIR-1 and inhibit immune cell activation in vitro. LAIR-1 binds multiple sites on collagens II and III (Lebbink et al. 2009). LAIR-1 and LAIR-2 are high affinity receptors for collagens I and III. They bind to them with higher affinity than GPVI (Lebbink et al. 2006, Lebbink et al. 2008), but three LAIR-1 amino acids central to collagen binding are conserved in GPVI (Brondijk et al. 2010). Fibril-forming collagens and collagen IV are also ligands of Endo180 (urokinase-type plasminogen activator associated protein), a member of the macrophage mannose-receptor family that mediates collagen internalization (Leitinger and Hohenester 2007; Heino et al. 2009). The identification of collagen sequences that bind to receptors has benefited from the Toolkits (overlapping synthetic trimeric peptides encompassing the entire triple-helical domain of human collagens II and III) developed by Farndale et al. (2008).

FUNCTIONS OF COLLAGENS

Fibrillar collagens are the most abundant collagens in vertebrates where they play a structural role by contributing to the molecular architecture, shape, and mechanical properties of tissues such as the tensile strength in skin and the resistance to traction in ligaments (Kadler 1995, Ricard-Blum et al. 2000). Several collagens, once referred to as “minor” collagens, are crucial for tissue integrity despite the fact that they are present in very small amounts. Collagen IX comprises 1% of collagen in adult articular cartilage (Martel-Pelletier et al. 2008) and collagen VII, crucial for skin integrity, constitutes only about 0.001% of total collagens in skin (Bruckner-Tuderman et al. 1987). Excess collagen is deposited in the extracellular matrix during fibrosis and fibrillogenesis is a new target to limit fibrosis by blocking telopeptide-mediated interactions of collagen molecules (Chung et al. 2008). Collagens are no longer restricted to a triple helix, banded fibrils or to a structural and scaffold role. As stated by Hynes (2009) for the extracellular matrix, collagens are not “just pretty fibrils.” Collagens interact with cells through several receptors, and their roles in the regulation of cell growth, differentiation, and migration through the binding of their receptors is well documented.

Some collagen types with a restricted tissue distribution exert specific biological functions. Collagen VII is a component of anchoring fibrils, and participates in dermal-epidermal adhesion. Collagen X, expressed in hypertrophic cartilage, plays a role in endochondral ossification and contributes to the establishment of a hematopoietic niche at the chondro-osseous junction (Sweeney et al. 2010). Collagen XXII is present only at tissue junctions such as the myotendinous junction in skeletal and heart muscle (Koch et al. 2004). An association between COL22A1 and the level of serum creatinine, the most important biomarker for a quick assessment of kidney function, has been detected in a meta-analysis of genome-wide data. This association may reflect the biological relationship between muscle mass formation and creatinine levels (Pattaro et al. 2010). Collagen XXIV is a marker of osteoblast differentiation and bone formation (Matsuo et al. 2008), and collagen XXVII appears to be restricted mainly to cartilage into adulthood. It is associated with cartilage calcification and could play a role in the transition of cartilage to bone during skeletogenesis (Hjorten et al. 2007). Its involvement in skeletogenesis has been confirmed in zebra fish where it plays a role in vertebral mineralization and postembryonic axial growth (Christiansen et al. 2009). The α5(VI) chain is not expressed in the outer epidermis of patients with atopic dermatitis, a chronic inflammatory skin disorder and a manifestation of allergic disease, suggesting that it contributes to the integrity and function of the epidermis (Söderhäll et al. 2007). The association of COL6A5/COL29A1 with atopy has been confirmed at the genetic level (Castro-Giner et al. 2009). The gene coding for the α1 chain of collagen XVIII has also been identified as a new potential candidate gene for atopy (Castro-Giner et al. 2009).

The four membrane collagens seem to fulfill different functions. Collagen XIII affects bone formation and may have a function in coupling the regulation of bone mass to mechanical use (Ylönen et al. 2005). Collagen XVII is a major structural component of the hemidesmosome (Has and Kern 2010), whereas collagen XXIII is associated with prostate cancer recurrence and distant metastases (Banyard et al. 2007). However, membrane collagens XIII, XVII (Seppänen et al. 2006), and XXV (Hashimoto et al. 2002) are expressed in neurons, or neuronal structures, and collagen XXVIII is predominantly expressed in neuronal tissue (Veit et al. 2006). New roles of collagens have been found in the development of the vertebrate nervous system, when collagen IV plays a role at the neuromuscular junction as a presynaptic organizer (Fox et al. 2007, 2008). Collagen XIX is expressed by central neurons, and is necessary for the formation of hippocampal synapses (Su et al. 2010). Several collagens (IV, VI, XVIII, and XXV) are deposited in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease where they bind to the amyloid β peptide. Furthermore, there is genetic evidence of association between the COL25A1 gene and risk for Alzheimer’s disease (Forsell et al. 2010). Collagen VI seems to protect neurons against Aβ toxicity (Cheng et al. 2009).

MATRICRYPTINS OF COLLAGENS

Bioactive fragments released by proteolytic cleavage of collagens regulate a number of physiological and pathological processes such as development, angiogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis, and tissue repair (Nyberg et al. 2005; Ricard-Blum and Ballut 2011). These fragments, called matricryptins, increase the functional diversity of collagens because most of them possess biological activities that are different from their parent molecule. A single collagen type can give rise to several matricryptins (collagen IV) (Table 3). Most collagen matricryptins are derived from basement membrane collagens (collagens IV, VIII, and XVIII) (Table 3) or located in the basement membrane zone (collagens XV and XIX) and show antiangiogenic and antitumoral properties (Nyberg et al. 2005, Ricard-Blum and Ballut 2011). Endostatin, the carboxy-terminal fragment of collagen XVIII, and tumstatin, the carboxy-terminal domain of the α3(IV) chain, have been extensively studied. The extracellular domains of membrane collagens released by shedding because of furin-like proprotein convertases (collagens XIII, XXIII, XXV), or ADAM-9 and ADAM-10 (collagen XVII) (Franzke et al. 2009) show paracrine activities and might be considered as matricryptins (Table 3). Matricryptins are potential drugs and Endostar, a derivative of endostatin, has been approved in 2005 in China for the treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer in conjunction with chemotherapy (Ling et al. 2007).

Table 3.

Major matricryptins of collagens.

| Collagens | Collagen α chain | Matricryptins | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen IV | α1(IV) chain | Arresten | NC1 |

| α2(IV) chain | Canstatin | NC1 | |

| α3(IV) chain | Tumstatin | NC1 | |

| α4(IV) chain | Tetrastatins 1-3 | ||

| α5(IV) chain | Pentastatins 1-3 | ||

| α6(IV) chain | NC1 α6(IV) Hexastatins 1-2 |

NC1 | |

| Collagen VIII | α1(VIII) chain | Vastatin | NC1 |

| Collagen XV | α1(XV) chain | Restin | NC1 |

| Collagen XVIII | α1(XVIII) chain | Endostatin | NC1 |

| Collagen XIX | α1(XIX) chain | NC1 |

GENETIC AND ACQUIRED DISEASES OF COLLAGENS

Several autoimmune disorders involve autoantibodies directed against collagens. Collagen VII is the autoantigen of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Ishii et al. 2010), and collagen XVII is the major autoantigen of the skin blistering disease bullous pemphigoid (Franzke et al. 2005). The NC1 domain of the α3(IV) chain contains the epitopes recognized by the antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies found in patients with Goodpasture syndrome characterized by glomerulonephritis and lung hemorrhage (Khoshnoodi et al. 2008). Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, the most common cause of lung transplant failure, is associated with a strong cellular immune response to collagen V (Burlingham et al. 2007).

Many disorders are caused by mutations in the genes coding for collagen α chains (Table 4) (Lampe and Bushby 2005; Callewaert et al. 2008; Bateman et al. 2009; Carter and Raggio 2009; Fine 2010). Mutations of collagen I, II, and III genes are catalogued in the human collagen mutation database (Dalgleish 1997, 1998) and in the COLdb database that links genetic data to molecular function in fibrillar collagens (Bodian and Klein 2009). Regions rich in osteogenesis imperfecta lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans in the helical domain of type I collagen (Marini et al. 2007). The mutations affect the extracellular matrix by decreasing the amount of secreted collagen(s), impairing molecular and supramolecular assembly through the secretion of a mutant collagen, or by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response (Bateman et al. 2009).

Table 4.

Genetic diseases because of mutations in collagen genes.

| Gene | Disease | References, databases |

|---|---|---|

| COL1A1 COL1A2 |

Osteogenesis imperfecta Ehlers–Danlos syndrome |

Marini et al. (2007) Dalgleish (1997, 1998) www.le.ac.uk/genetics/collagen Bodian and Klein (2009) http://collagen.stanford.edu/ |

| COL2A1 | Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia, Achondrogenesis, hypochondrogenesis Kniest dysplasia, Stickler syndrome |

Bodian and Klein (2009) http://collagen.stanford.edu/ |

| COL3A1 | Ehlers–Danlos syndrome |

Dalgleish (1997, 1998) www.le.ac.uk/genetics/collagen Bodian and Klein (2009) http://collagen.stanford.edu/ |

| COL4A1 | Familial porencephaly Hereditary angiopathy with nephropathy, aneurysms and muscle cramps syndrome |

Van Agtmael and Bruckner-Tuderman (2010) |

| COL4A3 COL4A4 | Alport syndrome Benign familial haematuria |

Van Agtmael and Bruckner-Tuderman (2010) |

| COL4A5 COL4A6 |

Alport syndrome Leiomyomatosis |

Bateman et al. (2009), Van Agtmael and Bruckner-Tuderman (2010) |

| COL5A1 COL5A2 |

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome | Callewaert et al. (2008) |

| COL6A1 COL6A2 COL6A3 |

Bethlem myopathy Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy |

Lampe and Bushby (2005) |

| COL7A1 | Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa | Fine (2010) |

| COL8A2 | Corneal endothelial dystrophies | Bateman et al. (2009) |

| COL9A1 COL9A2 |

Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia | Carter and Raggio (2009) |

| COL9A3 | Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia Autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome |

Carter and Raggio (2009) |

| COL10A1 | Schmid metaphyseal chondrodysplasia | Grant (2007) |

| COL11A1 | Stickler syndrome Marshall syndrome |

Carter and Raggio (2009) |

| COL11A2 | Stickler syndrome Marshall syndrome Otospondylomegaepiphyseal dysplasia Deafness |

Carter and Raggio (2009) |

| COL17A1 | Junctional epidermolysis bullosa-other | Has and Kern (2010) |

| COL18A1 | Knobloch syndrome | Nicolae and Olsen (2010) |

CONCLUDING REMARKS

During the last 40 years, the collagen field has evolved from collagen chemistry to cell therapy as recounted by Michael Grant (2007). Twenty-eight collagen types have been identified and characterized at the molecular level. Their functions have been determined either through direct assays or from the generation of knockout mice and the knowledge of defects occurring in tissues of patients with genetic diseases because of mutation(s) in genes coding for collagens. Cell therapy gives promising results for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (Kern et al. 2009; Conget et al. 2010), and osteogenesis imperfecta (Niyibizi and Li 2009). To understand how collagens work in a concerted fashion with their extracellular and cell-surface partners, a global, integrative approach is needed. Ligand-binding sites, functional domains and mutations have been mapped on the collagen I fibril that appears to be composed of cell interaction domains and matrix interaction domains (Sweeney et al. 2008). Defining the structures and functions of collagen domains along the collagen fibril will provide new insights into collagen fibril functions, and into their possible modulation, specifically in fibroproliferative diseases where collagen fibrillogenesis is a new target to limit fibrosis (Chung et al. 2008). The binding force between collagen and other proteins can be calculated by atomic microscopy, and these measurements, in addition to kinetics, affinity and thermodynamics data, could be used to hierarchize interactions participating in biological processes. Interaction data on collagens and other extracellular biomolecules are stored in a database called MatrixDB (http://matrixdb.ibcp.fr) (Chautard et al. 2009). These data can be used to build extracellular interaction networks of a molecule, a tissue or a disease and to make functional hypothesis. New tools to identify binding partners of a protein (protein and glycosaminoglycan arrays probed by surface plasmon resonance imaging (Faye et al. 2009, 2010), and a proteomics workflow to isolate complexes associated with integrin adhesion receptors (Humphries et al. 2009), will be helpful in deciphering the functions of collagens at the systems biology level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Romain Salza (UMR 5086 CNRS-University Lyon 1, France) is gratefully acknowledged for drawing the figures of the manuscript, and David J. Hulmes (UMR 5086 CNRS - University Lyon 1, France) for his critical reading of the manuscript and his suggestions.

Footnotes

Editors: Richard Hynes and Kenneth Yamada

Additional Perspectives on Extracellular Matrix Biology available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Amenta PS, Scivoletti NA, Newman MD, Sciancalepore JP, Li D, Myers JC 2005. Proteoglycan-collagen XV in human tissues is seen linking banded collagen fibers subjacent to the basement membrane. J Histochem Cytochem 53: 165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge HL, Meng X, Zhang G, Veit G, Sun M, Klement JF, Beason DP, Soslowsky LJ, Koch M, Birk DE 2009. Type XIV collagen regulates fibrillogenesis: premature collagen fibril growth and tissue dysfunction in null mice. J Biol Chem 284: 8427–8438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery NC, Bailey AJ 2006. The effects of the Maillard reaction on the physical properties and cell interactions of collagen. Pathol Biol 54: 387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader HL, Keene DR, Charvet B, Veit G, Driever W, Koch M, Ruggiero F 2009. Zebrafish collagen XII is present in embryonic connective tissue sheaths (fascia) and basement membranes. Matrix Biol 28: 32–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banos CC, Thomas AH, Kuo CK 2008. Collagen fibrillogenesis in tendon development: Current models and regulation of fibril assembly. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 84: 228–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard J, Bao L, Hofer MD, Zurakowski D, Spivey KA, Feldman AS, Hutchinson LM, Kuefer R, Rubin MA, Zetter BR 2007. Collagen XXIII expression is associated with prostate cancer recurrence and distant metastases. Clin Cancer Res 13: 2634–2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman JF, Boot-Handford RP, Lamandé SR 2009. Genetic diseases of connective tissues: Cellular and extracellular effects of ECM mutations. Nat Rev Genet 10: 173–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella J, Liu J, Kramer R, Brodsky B, Berman HM 2006. Conformational effects of Gly-X-Gly interruptions in the collagen triple helix. J Mol Biol 362: 298–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodian DL, Klein TE 2009. COLdb, a database linking genetic data to molecular function in fibrillar collagens. Hum Mutat 30: 946–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogin O, Kvansakul M, Rom E, Singer J, Yayon A, Hohenester E 2002. Insight into Schmid metaphyseal chondrodysplasia from the crystal structure of the collagen X NC1 domain trimer. Structure 10: 165–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borza DB, Bondar O, Ninomiya Y, Sado Y, Naito I, Todd P, Hudson BG 2001. The NC1 domain of collagen IV encodes a novel network composed of the α1, α2, α5, and α6 chains in smooth muscle basement membranes. J Biol Chem 276: 28532–28640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudko SP, Engel J, Bächinger HP 2008. Trimerization and triple helix stabilization of the collagen XIX NC2 domain. J Biol Chem 283: 34345–34351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudko SP, Sasaki T, Engel J, Lerch TF, Nix J, Chapman MS, Bächinger HP 2009. Crystal structure of human collagen XVIII trimerization domain: A novel collagen trimerization fold. J Mol Biol 392: 787–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudko SP, Zientek KD, Vance JM, Hacker JL, Engel J, Bachinger HP 2010. The NC2 domain of collagen IX provides chain selection and heterotrimerization. J Biol Chem 285: 23721–23731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondijk TH, de Ruiter T, Ballering J, Wienk H, Lebbink RJ, van Ingen H, Boelens R, Farndale RW, Meyaard L, Huizinga EG 2010. Crystal structure and collagen-binding site of immune inhibitory receptor LAIR-1: unexpected implications for collagen binding by platelet receptor GPVI. Blood 115: 1364–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner P 2010. Suprastructures of extracellular matrices: Paradigms of functions controlled by aggregates rather than molecules. Cell Tissue Res 339: 7–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman L, Schnyder UW, Winterhalter KH, Bruckner P 1987. Tissue form of type VII collagen from human skin and dermal fibroblasts in culture. Eur J Biochem 165: 607–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlingham WJ, Love RB, Jankowska-Gan E, Haynes LD, Xu Q, Bobadilla JL, Meyer KC, Hayney MS, Braun RK, Greenspan DS, et al. 2007. IL-17-dependent cellular immunity to collagen type V predisposes to obliterative bronchiolitis in human lung transplants. J Clin Invest 117: 3498–3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert B, Malfait F, Loeys B, De Paepe A 2008. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and Marfan syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 22: 165–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canty EG, Lu Y, Meadows RS, Shaw MK, Holmes DF, Kadler KE 2004. Coalignment of plasma membrane channels and protrusions (fibripositors) specifies the parallelism of tendon. J Cell Biol 165: 553–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli F, Bihan D, Stathopoulos S, Konitsiotis AD, Kvansakul M, Farndale RW, Leitinger B, Hohenester E 2009. Crystallographic insight into collagen recognition by discoidin domain receptor 2. Structure 17: 1573–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EM, Raggio CL 2009. Genetic and orthopedic aspects of collagen disorders. Curr Opin Pediatr 21: 46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Giner F, Bustamante M, Ramon González J, Kogevinas M, Jarvis D, Heinrich J, Antó JM, Wjst M, Estivill X, de Cid R 2009. A pooling-based genome-wide analysis identifies new potential candidate genes for atopy in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS). BMC Med Genet 10: 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chautard E, Ballut L, Thierry-Mieg N, Ricard-Blum S 2009. MatrixDB, a database focused on extracellular protein-protein and protein-carbohydrate interactions. Bioinformatics 25: 690–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JS, Dubal DB, Kim DH, Legleiter J, Cheng IH, Yu GQ, Tesseur I, Wyss-Coray T, Bonaldo P, Mucke L 2009. Collagen VI protects neurons against Abeta toxicity. Nat Neurosci 12: 119–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen HE, Lang MR, Pace JM, Parichy DM 2009. Critical early roles for col27a1a and col27a1b in zebrafish notochord morphogenesis, vertebral mineralization and post-embryonic axial growth. PLoS One 4: e8481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Steplewski A, Chung KY, Uitto J, Fertala A 2008. Collagen fibril formation. A new target to limit fibrosis. J Biol Chem 283: 25879–25886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conget P, Rodriguez F, Kramer S, Allers C, Simon V, Palisson F, Gonzalez S, Yubero MJ 2010. Replenishment of type VII collagen and re-epithelialization of chronically ulcerated skin after intradermal administration of allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells in two patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Cytotherapy 12: 429–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish R 1997. The human type I collagen mutation database. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish R 1998. The human collagen mutation database. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 253–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C, Caputo I 2005. Mammalian transglutaminases Identification of substrates as a key to physiological function and physiopathological relevance. FEBS J 272: 615–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre DR, Wu JJ 2005. Collagen cross-links. Top Curr Chem 247: 207–230 [Google Scholar]

- Eyre DR, Weis MA, Wu JJ 2010. Maturation of collagen ketoimine cross-links by an alternative mechanism to pyridinoline formation in cartilage. J Biol Chem 285: 16675–16682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallas JA, Gauba V, Hartgerink JD 2009. Solution structure of an ABC collagen heterotrimer reveals a single-register helix stabilized by electrostatic interactions. J Biol Chem 284: 26851–26859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farndale RW, Lisman T, Bihan D, Hamaia S, Smerling CS, Pugh N, Konitsiotis A, Leitinger B, de Groot PG, Jarvis GE, et al. 2008. Cell-collagen interactions: the use of peptide Toolkits to investigate collagen-receptor interactions. Biochem Soc Trans 36: 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye C, Chautard E, Olsen BR, Ricard-Blum S 2009. The first draft of the endostatin interaction network. J Biol Chem 284: 22041–22047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye C, Inforzato A, Bignon M, Hartmann DJ, Muller L, Ballut L, Olsen BR, Day AJ, Ricard-Blum S 2010. Transglutaminase-2: A new endostatin partner in the extracellular matrix of endothelial cells. Biochem J 427: 467–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JD 2010. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa: Recent basic and clinical advances. Curr Opin Pediatr 22: 453–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn LA, Blissett AR, Calomeni EP, Agarwal G 2010. Inhibition of collagen fibrillogeesis by cells expressing soluble extracellular domains of DDR1 and DDR2. J Mol Biol 395: 533–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsell C, Björk BF, Lilius L, Axelman K, Fabre SF, Fratiglioni L, Winblad B, Graff C 2010. Genetic association to the amyloid plaque associated protein gene COL25A1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 31: 409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MA 2008. Novel roles for collagens in wiring the vertebrate nervous system. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20: 508–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MA, Sanes JR, Borza DB, Eswarakumar VP, Fässler R, Hudson BG, John SW, Ninomiya Y, Pedchenko V, Pfaff SL, et al. 2007. Distinct target-derived signals organize formation, maturation, and maintenance of motor nerve terminals. Cell 129: 179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke CW, Bruckner P, Bruckner-Tuderman L 2005. Collagenous transmembrane proteins: recent insights into biology and pathology. J Biol Chem 280: 4005–4008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke CW, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Blobel CP 2009. Shedding of collagen XVII/BP180 in skin depends on both ADAM10 and ADAM9. J Biol Chem 284: 23386–23396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DA, Tenner AJ 2008. Directing an appropriate immune response: the role of defense collagens and other soluble pattern recognition molecules. Curr Drug Targets 9: 113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gara SK, Grumati P, Urciuolo A, Bonaldo P, Kobbe B, Koch M, Paulsson M, Wagener R 2008. Three novel collagen VI chains with high homology to the alpha3 chain. J Biol Chem 283: 10658–10670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay S, Miller EJ 1983. What is collagen, what is not. Ultrastruct Pathol 4: 365–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MK, Hahn RA 2010. Collagens. Cell Tissue Res 339: 247–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant ME 2007. From collagen chemistry towards cell therapy—a personal journey. Int J Exp Pathol 88: 203–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan DS 2005. Biosynthetic processing of collagen molecules. Top Curr Chem 247: 149–183 [Google Scholar]

- Gutsmann T, Fantner GE, Kindt JH, Venturoni M, Danielsen S, Hansma PK 2004. Force spectroscopy of collagen fibers to investigate their mechanical properties and structural organization. Biophys J 86: 3186–3193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Makareeva E, Kuznetsova N, DeRidder AM, Sutter MB, Losert W, Phillips CL, Visse R, Nagase H, Leikin S 2010. Molecular mechanism of type I homotrimer resistance to mammalian collagenases. J Biol Chem 285: 22276–22281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has C, Kern JS 2010. Collagen XVII. Dermatol Clin 28: 61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Wakabayashi T, Watanabe A, Kowa H, Hosoda R, Nakamura A, Kanazawa I, Arai T, Takio K, Mann DM, et al. 2002. CLAC: A novel Alzheimer amyloid plaque component derived from a transmembrane precursor, CLAC-P/collagen type XXV. EMBO J 21: 1524–1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heino J 2007. The collagen family members as cell adhesion proteins. Bioessays 29: 1001–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heino J, Huhtala M, Käpylä J, Johnson MS 2009. Evolution of collagen-based adhesion systems. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorten R, Hansen U, Underwood RA, Telfer HE, Fernandes RJ, Krakow D, Sebald E, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Bruckner P, Jacquet R, et al. 2007. . Type XXVII collagen at the transition of cartilage to bone during skeletogenesis. Bone 41: 535–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DF, Kadler KE 2006. The 10+4 microfibril structure of thin cartilage fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 17249–17254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins DR, Keles S, Greenspan DS 2007. The bone morphogenetic protein 1/Tolloid-like metalloproteinases. Matrix Biol 26: 508–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ 2006. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci 119: 3901–3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JD, Byron A, Bass MD, Craig SE, Pinney JW, Knight D, Humphries MJ 2009. Proteomic analysis of integrin-associated complexes identifies RCC2 as a dual regulator of Rac1 and Arf6. Sci Signal 2: ra51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurskainen M, Ruggiero F, Hägg P, Pihlajaniemi T, Huhtala P 2010. Recombinant human collagen XV regulates cell adhesion and migration. J Biol Chem 285: 5258–5265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, Karashima T, Nakama T, Yasumoto S, Zillikens D, Hashimoto T 2010. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: What’s new? J Dermatol 37: 220–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO 2009. The extracellular matrix: Not just pretty fibrils. Science 326: 1216–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadler K 1995. Extracellular matrix 1: Fibril-forming collagens. Protein Profile 2: 491–619 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadler KE, Hill A, Canty-Laird EG 2008. Collagen fibrillogenesis: Fibronectin, integrins, and minor collagens as organizers and nucleators. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20: 495–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadler KE, Baldock C, Bella J, Boot-Handford RP 2007. Collagens at a glance. J Cell Sci 120: 1955–1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamajski S, Oldberg A 2010. The role of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in collagen fibrillogenesis. Matrix Biol 29: 248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassner A, Hansen U, Miosge N, Reinhardt DP, Aigner T, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Bruckner P, Grässel S 2003. Discrete integration of collagen XVI into tissue-specific collagen fibrils or beaded microfibrils. Matrix Biol 22: 131–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JS, Loeckermann S, Fritsch A, Hausser I, Roth W, Magin TM, Mack C, Müller ML, Paul O, Ruther P, et al. 2009. Mechanisms of fibroblast cell therapy for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: High stability of collagen VII favors long-term skin integrity. Mol Ther 17: 1605–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnoodi J, Pedchenko V, Hudson BG 2008. Mammalian collagen IV. Microsc Res Tech 71: 357–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnoodi J, Cartailler JP, Alvares K, Veis A, Hudson BG 2006. Molecular recognition in the assembly of collagens: Terminal noncollagenous domains are key recognition modules in the formation of triple helical protomers. J Biol Chem 281: 38117–38121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein T, Bischoff R 2010. Physiology and pathophysiology of matrix metalloproteases. Amino Acids doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0689-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Koch M, Schulze J, Hansen U, Ashwodt T, Keene DR, Brunken WJ, Burgeson RE, Bruckner P, Bruckner-Tuderman L 2004. A novel marker of tissue junctions, collagen XXII. J Biol Chem 279: 22514–22521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvansakul M, Bogin O, Hohenester E, Yayon A 2003. Crystal structure of the collagen α1(VIII) NC1 trimer. Matrix Biol 22: 145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe AK, Bushby KM 2005. Collagen VI related muscle disorders. J Med Genet 4: 673–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebbink RJ, de Ruiter T, Adelmeijer J, Brenkman AB, van Helvoort JM, Koch M, Farndale RW, Lisman T, Sonnenberg A, Lenting PJ, et al. 2006. Collagens are functional, high affinity ligands for the inhibitory immune receptor LAIR-1. J Exp Med 203: 1419–1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebbink RJ, Raynal N, de Ruiter T, Bihan DG, Farndale RW, Meyaard L 2009. Identification of multiple potent binding sites for human leukocyte associated Ig-like receptor LAIR on collagens II and III. Matrix Biol 28: 202–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebbink RJ, van den Berg MC, de Ruiter T, Raynal N, van Roon JA, Lenting PJ, Jin B, Meyaard L 2008. The soluble leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor (LAIR)-2 antagonizes the collagen/LAIR-1 inhibitory immune interaction. J Immunol 180: 1662–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitinger B, Hohenester E 2007. Mammalian collagen receptors. Matrix Biol 26: 146–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y, Yang Y, Lu N, You QD, Wang S, Gao Y, Chen Y, Guo QL 2007. Endostar, a novel recombinant human endostatin, exerts antiangiogenic effect via blocking VEGF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of KDR/Flk-1 of endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 361: 79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertens B, Hopkins D, Franzke CW, Keene DR, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Greenspan DS, Koch M 2007. Cleavage and oligomerization of gliomedin, a transmembrane collagen required for node of Ranvier formation. J Biol Chem 282: 10647–10659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makareeva E, Leikin S 2007. Procollagen triple helix assembly: An unconventional chaperone-assisted folding paradigm. PLoS One 2: e1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäki JM 2009. Lysyl oxidases in mammalian development and certain pathological conditions. Histol Histopathol 24: 651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini JC, Forlino A, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, San Antonio JD, Milgrom S, Hyland JC, Körkkö J, Prockop DJ, De Paepe A, et al. 2007. Consortium for osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in the helical domain of type I collagen: Regions rich in lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans. Hum Mutat 28: 209–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinek N, Shahab J, Sodek J, Ringuette M 2007. Is SPARC an evolutionarily conserved collagen chaperone? Dent Res 86: 296–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel-Pelletier J, Boileau C, Pelletier JP, Roughley PJ 2008. Cartilage in normal and osteoarthritis conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 22: 351–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo N, Tanaka S, Yoshioka H, Koch M, Gordon MK, Ramirez F 2008. Collagen XXIV (Col24a1) gene expression is a specific marker of osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Connect Tissue Res 49: 68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne R, Brewton RG, Mayne PM, Baker JR 1993. Isolation and characterization of the chains of type V/type XI collagen present in bovine vitreous. J Biol Chem 268: 9381–9386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EJ, Gay S Collagen: An overview. 1982. Methods Enzymol 82: 3–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EJ, Matukas VJ Chick cartilage collagen: A new type of α1 chain not present in bone or skin of the species. 1969. Proc Natl Acad Sci 64: 1264–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G 2009. Regulation of the proteolytic disintegrin metalloproteinases, the ‘sheddases.’ Sem Cell Dev Biol 20: 138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JC, Amenta PS, Dion AS, Sciancalepore JP, Nagaswami C, Weisel JW, Yurchenco PD 2007. The molecular structure of human tissue type XV presents a unique conformation among the collagens. Biochem J 404: 535–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllyharju J, Kivirikko KI 2004. Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet 20: 33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyibizi C, Li F 2009. Potential implications of cell therapy for osteogenesis imperfecta. Int J Clin Rheumatol 4: 57–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg P, Xie L, Kalluri R 2005. Endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis. Cancer Res 65: 3967–3979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen BR 1997. Collagen IX. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 29: 555–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgel JP, Irving TC, Miller A, Wess TJ 2006. Microfibrillar structure of type I collagen in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 9001–9005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattaro C, De Grandi A, Vitart V, Hayward C, Franke A, Aulchenko YS, Johansson A, Wild SH, Melville SA, Isaacs A, et al. 2010. A meta-analysis of genome-wide data from five European isolates reveals an association of COL22A1, SYT1, and GABRR2 with serum creatinine level. BMC Med Genet 11: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persikov AV, Ramshaw JA, Kirkpatrick A, Brodsky B 2005. Electrostatic interactions involving lysine make major contributions to collagen triple-helix stability. Biochemistry 44: 1414–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumb DA, Dhir V, Mironov A, Ferrara L, Poulsom R, Kadler KE, Thornton DJ, Briggs MD, Boot-Handford RP 2007. Collagen XXVII is developmentally regulated and forms thin fibrillar structures distinct from those of classical vertebrate fibrillar collagens. J Biol Chem 282: 12791–12795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S, Ballut L 2011. Matricryptins from collagens and proteoglycans. Front Biosci 16: 674–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S, Ruggiero F 2005. The collagen superfamily: from the extracellular matrix to the cell membrane. Pathol Biol 53: 430–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S, Dublet B, van der Rest M 2000. Unconventional Collagens: Types VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XII, XIV, XVI and XIX. Protein Profile Series Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S, Ruggiero F, van der Rest M 2005. The collagen superfamily. Top Curr Chem 247: 35–84 [Google Scholar]

- Robins SP 2007. Biochemistry and functional significance of collagen cross-linking. Biochem Soc Trans 35: 849–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Marumo K 2010. Collagen cross-links as a determinant of bone quality: a possible explanation for bone fragility in aging, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int 21: 195–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Fukai N, Mann K, Göhring W, Olsen BR, Timpl R 1998. Structure, function and tissue forms of the C-terminal globular domain of collagen XVIII containing the angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin. EMBO J 17: 4249–4256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauk JJ, Nikitakis N, Siavash H 2005. Hsp47 a novel collagen binding serpin chaperone, autoantigen and therapeutic target. Front Biosci 10: 107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppänen A, Autio-Harmainen H, Alafuzoff I, Särkioja T, Veijola J, Hurskainen T, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Tasanen K, Majamaa K 2006. Collagen XVII is expressed in human CNS neurons. Matrix Biol 25: 185–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Olsen BR 1991. FACIT collagens: Diverse molecular bridges in extracellular matrices. Trends Biochem Sci 16: 191–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar L, Agarwal G 2010. The influence of discoidin domain receptor 2 on the persistence length of collagen type I fibers. Biomaterials 31: 4802–4808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg JS, Bulterijs S 2009. Characteristics, formation, and pathophysiology of glucosepane: a major protein cross-link. Rejuvenation Res 12: 137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderhäll C, Marenholz I, Kerscher T, Rüschendorf F, Esparza-Gordillo J, Worm M, Gruber C, Mayr G, Albrecht M, Rohde K, et al. 2007. Variants in a novel epidermal collagen gene (COL29A1) are associated with atopic dermatitis. PLoS Biol 5: e242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J, Gorse K, Ramirez F, Fox MA 2010. Collagen XIX is expressed by interneurons and contributes to the formation of hippocampal synapses. J Comp Neurol 518: 229–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaramoorthy M, Meiyappan M, Todd P, Hudson BG 2002. Crystal structure of NC1 domains. Structural basis for type IV collagen assembly in basement membranes. J Biol Chem 277: 31142–31153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney SM, Orgel JP, Fertala A, McAuliffe JD, Turner KR, Di Lullo GA, Chen S, Antipova O, Perumal S, Ala-Kokko L, et al. 2008. Candidate cell and matrix interaction domains on the collagen fibril, the predominant protein of vertebrates. J Biol Chem 283: 21187–21197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney E, Roberts R, Corbo T, Jacenko O 2010. Congenic mice confirm that collagen X is required for proper hematopoietic development. PLoS One 5: e9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Than ME, Henrich S, Huber R, Ries A, Mann K, Kühn K, Timpl R, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Bode W 2002. The 1.9-A crystal structure of the noncollagenous (NC1) domain of human placenta collagen IV shows stabilization via a novel type of covalent Met-Lys cross-link. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 6607–6612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Rest M, Garrone R 1991. Collagen family of proteins. FASEB J 5: 2814–2823 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacore RM, Friedman DB, Ham AJ, Sundaramoorthy M, Hudson BG 2005. Identification of S-hydroxylysyl-methionine as the covalent cross-link of the noncollagenous (NC1) hexamer of the α1α1α2 collagen IV network: A role for the post-translational modification of lysine 211 to hydroxylysine 211 in hexamer assembly. J Biol Chem 280: 29300–29310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacore R, Ham AJ, Voehler M, Sanders CR, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Sharpless KB, Dawson PE, Hudson BG 2009. A sulfilimine bond identified in collagen IV. Science 325: 1230–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacore RM, Shanmugasundararaj S, Friedman DB, Bondar O, Hudson BG, Sundaramoorthy M 2004. The α1.α2 network of collagen IV. Reinforced stabilization of the noncollagenous domain-1 by noncovalent forces and the absence of Met-Lys cross-links. J Biol Chem 279: 44723–44730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Agtmael T, Bruckner-Tuderman L 2010. Basement membranes and human disease. Cell Tissue Res 339: 167–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veit G, Kobbe B, Keene DR, Paulsson M, Koch M, Wagener R 2006. Collagen XXVIII, a novel von Willebrand factor A domain-containing protein with many imperfections in the collagenous domain. J Biol Chem 281: 3494–3504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villone D, Fritsch A, Koch M, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Hansen U, Bruckner P 2008. Supramolecular interactions in the dermo-epidermal junction zone: Anchoring fibril-collagen VII tightly binds to banded collagen fibrils. J Biol Chem 283: 24506–24513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MA, Hudson DM, Kim L, Scott M, Wu JJ, Eyre DR 2010. Location of 3-hydroxyproline residues in collagens I, II, III, ad V/XI implies a role in fibril supramolecular assembly. J Biol Chem 285: 2580–2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenstrup RJ, Florer JB, Brunskill EW, Bell SM, Chervoneva I, Birk DE 2004. Type V collagen controls the initiation of collagen fibril assembly. J Biol Chem 279: 53331–53337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JJ, Weis MA, Kim LS, Carter BG, Eyre DR 2009. Differences in chain usage and cross-linking specificities of cartilage type V/XI collagen isoforms with age and tissue. J Biol Chem 284: 5539–5545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JJ, Weis MA, Kim LS, Eyre DR 2010. Type III collagen, a fibril network modifier in articular cartilage. J Biol Chem 285: 18537–18544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylönen R, Kyrönlahti T, Sund M, Ilves M, Lehenkari P, Tuukkanen J, Pihlajaniemi T 2005. Type XIII collagen strongly affects bone formation in transgenic mice. J Bone Miner Res 20: 1381–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Young BB, Ezura Y, Favata M, Soslowsky LJ, Chakravarti S, Birk DE 2005. Development of tendon structure and function: Regulation of collagen fibrillogenesis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 5: 5–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]