Abstract

Summary: With the continuous growth of the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), providing an up-to-date systematic structure comparison of all protein structures poses an ever growing challenge. Here, we present a comparison tool for calculating both 1D protein sequence and 3D protein structure alignments. This tool supports various applications at the RCSB PDB website. First, a structure alignment web service calculates pairwise alignments. Second, a stand-alone application runs alignments locally and visualizes the results. Third, pre-calculated 3D structure comparisons for the whole PDB are provided and updated on a weekly basis. These three applications allow users to discover novel relationships between proteins available either at the RCSB PDB or provided by the user.

Availability and Implementation: A web user interface is available at http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/workbench/workbench.do. The source code is available under the LGPL license from http://www.biojava.org. A source bundle, prepared for local execution, is available from http://source.rcsb.org

Contact: andreas@sdsc.edu; pbourne@ucsd.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

At its core, the RCSB PDB Protein Comparison Tool contains a new implementation of the two structure alignment algorithms Combinatorial Extension (CE) (Shindyalov and Bourne, 1998) and FATCAT (both rigid body and flexible versions) (Ye and Godzik, 2003).

Both the CE and FATCAT algorithms detect aligned fragment pairs (AFPs) during the alignment process. These AFPs are based on similarities in local geometry. There is a difference in how initial AFPs are combined in order to calculate an optimal alignment. CE applies the process of ‘Combinatorial Extension’ to find possible continuous alignment paths leading to an optimal alignment. The resulting alignment is a ‘rigid-body’ based alignment. In contrast to this, FATCAT allows the introduction of ‘twists’ into the alignment with the consequence that different regions of a protein structures can undergo different geometric transformations. This is required in order to be able to deal with protein flexibility.

A protein that undergoes significant domain re-arrangement during iron binding is transferrin. It consists of two domains that can move relative to each other. FATCAT in its flexible mode can easily detect an alignment between the apo and holo forms that covers 95% of both protein chains. (e.g. PDB ID 1IEJ chain A and PDB ID 1BTJ chain A). However, using rigid body superposition only a partial alignment is possible (both CE and FATCAT using the rigid mode only). One drawback of the flexible mode is that if distantly related proteins are being aligned, sometimes twists between unrelated regions can be introduced (e.g. alignment of PDB ID 1CDG chain A and PDB ID 1TIM chain A), in which case it is better to run the alignments in rigid mode.

A limitation of both CE and FATCAT in their original versions is that they compute sequence order-dependent alignments. A number of difficult to detect relationships between proteins have been published, some of which require sequence order independence for a correct alignment (Andreeva et al., 2006). An algorithm that can detect such order-independet alignments is Triangle Match (Bachar et al., 1993; Nussinov and Wolfson, 1991). Dali in its early versions also could detect permutated proteins; however, this feature seems to have been lost in its recent implementations, (Holm and Sander, 1993). We have recently improved CE to be able to detect circularly permutated alignments (Bliven et al., manuscript in preparation). This implementation is available as an option of the RCSB Protein Comparison Tool.

2 APPROACH

The CE and FATCAT algorithms have been re-implemented in the Java programming language, which is indicated by a lower-case j in front of the new names, jCE and jFATCAT. Several components were added to these implementations.

First, the alignment algorithms were integrated into the RCSB PDB website, Berman et al., (2000) to provide a novel structure alignment service. Second, a stand-alone application can be run using Java Web Start technology. Third, a client-server architecture was developed for calculating large-scale comparisons using compute clouds. Finally, a software bundle is provided that allows local installation of the tool and to run custom comparisons. We describe some of these components in more detail.

Pairwise sequence and structure alignment

The comparison tool allows pairwise comparison of protein sequences and 3D structures. For sequence comparison the Smith–Waterman (Smith and Waterman, 1981), Needleman–Wunsch (Needleman and Wunsch, 1970) and blast2seq (Tatusova and Madden, 1999), algorithms are provided. Support for structure comparisons includes the new implementations of CE and FATCAT and links to some of the most prominent external protein structure alignment services: the original FATCAT server (Ye and Godzik, 2004), Mammoth (Ortiz et al., 2002), TM-align (Zhang and Skolnick, 2005) and Topmatch, (Sippl and Wiederstein, 2008), (Sippl, 2008). Other available structure alignment software can be found at Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structural_alignment_software

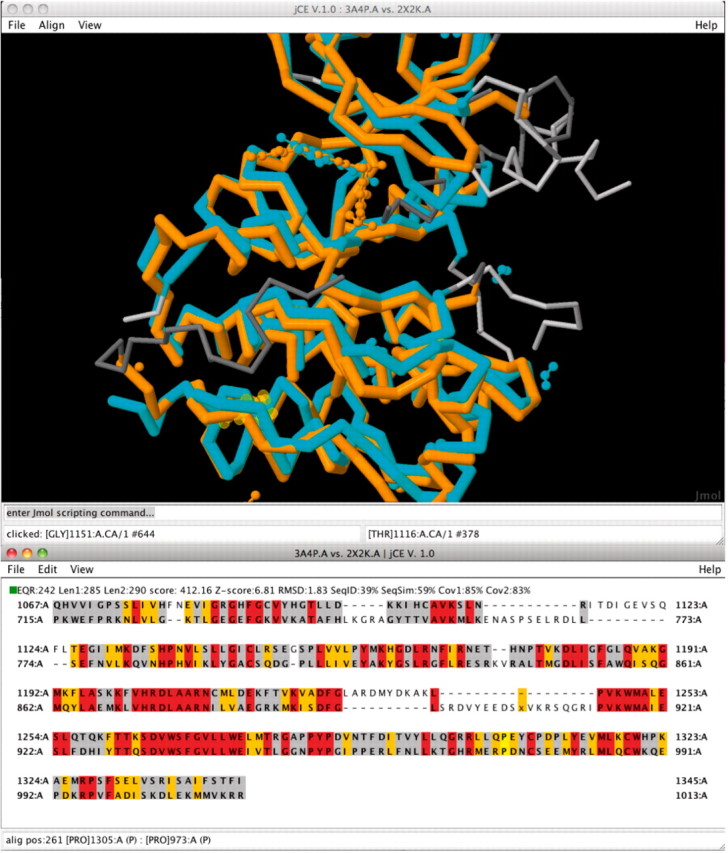

All alignments that are run using jCE and jFATCAT are calculated server-side on the fly and cached for future retrieval using XML files. If the alignment is requested again later, it can be instantly returned by reading the XML file. A web user interface provides access to the alignment results. Alternatively, a Java Web Start client application, based on Jmol (2010), and BioJava (Holland et al., 2008), provides a novel 3D visualization tool that allows the investigation of sequence–structure relationships between two aligned proteins. See Figure 1 for an example alignment.

Fig. 1.

A new user interface for jCE and jFATCAT structure alignments allows the investigation of sequence and 3D structure relationships. Here, the alignment of two kinases, the Hepatocyte growth factor receptor PDB ID 3A4P and the Proto-Oncogene Tyrosine-Protein Kinase Receptor RET PDB ID 2X2K. If the structures contain ligands they are also superimposed and displayed. The coloring for the sequence representation of the structure alignment represents the sequence conservation: red: identical residues, orange: similar and grey: structurally equivalent, but sequence mismatch.

Systematic structure alignments across the PDB

Sequence data-base searches are a frequently used tool to identify closely related proteins within a database. However, with decreasing sequence similarity relationships between proteins become harder to detect. In order to enable identification of relationships across the PDB, even if sequence similarity is low, we are providing systematic and precomputed alignments.

The procedure providing pre-computed structure comparisons across the PDB is split into two steps.

First, the goal is to reduce the complexity of the problem by identifying representative protein chains for clusters of related proteins. BLASTClust (Altschul et al., 2004) is used to cluster all protein chains by sequence similarity. We require 90% overlap between all sequences in a cluster. Therefore, a shorter fragment (e.g. a single domain) of a longer sequence (e.g. a multi-domain protein) will usually not be in the same cluster as the whole sequence. Within clusters, sequences are ranked by experimental method, resolution and release date. While the RCSB PDB website provides sequence comparisons for various levels of sequence identity within a cluster, structural comparisons are only provided based on clusters with 40% sequence identity, currently approximately 16000 representative protein chains.

Second, the rigid version of jFATCAT is used to calculate all-against-all 3D structure comparisons across all representative protein chains. This requires a significant amount of CPU time. Specifically, a client-server architecture has been developed that allows the user to easily run a large number of jobs in parallel (for details see http://www.renci.org/publications/techreports/TR-09-03.pdf). A total of 122 million alignments were calculated on the Open Science Grid, taking approximately 102 000 CPU hours. Another 18 million alignments were calculated on the San Diego Supercomputing Center (SDSC) Triton Cluster and local RCSB PDB servers. The alignment results were stored in ∼1 terabyte of XML files.

Weekly updates

Incremental updates to the all-against-all comparisons are run weekly using in-house RCSB PDB servers at the same time the PDB itself is updated. Every week new sequence clusters are calculated and missing alignments for newly added representative chains are calculated. At present, an average weekly update requires the calculation of about 1 million structure alignments.

3 DISCUSSION

The RCSB PDB website now provides a state of the art protein comparison tool that can be used as a web service and for local access. Further, pre-calculated all-against-all comparisons of sequences and 3D protein structures, respectively, are provided on a weekly basis. Currently, the calculations are done on a whole-chain basis. We are working on another set of comparisons using domain-based comparisons of all chains with an enhanced version of jCE that includes handling of circular permutations. An alternative is to use TOPS++FATCAT (Veeramalai et al., 2008), which provides a 10-fold speed up as compared to FATCAT. The domain assignment problem is non-trivial, and for newly released protein structures results are not immediately available from classifications like SCOP (Andreeva et al., 2008), or CATH (Cuff et al., 2009). Hence, we are investigating whether consensus based approaches like pDomains, (Alden et al., 2010), can guide which domain assignments to use for the automated calculations.

Funding: The RCSB PDB is managed by two members of the RCSB: Rutgers and UCSD, and is funded by National Science Foundation (NSF), National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Department of Energy (DOE), National Library of Medicine, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The RCSB PDB is a member of the wwPDB. This work was supported by the RCSB PDB grant NSF DBI 0829586. Computation provided in part by the Open Science Grid funded by NSF and DOE, supported by OSG Engagement under NSF award number 0753335.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Alden K, et al. dconsensus: a tool for displaying domain assignments by multiple structure-based algorithms and for construction of a consensus assignment. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:310. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, et al. BLASTClust. 2004 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Web/Newsltr/Spring04/blastlab.html (last accessed date October 20, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva A, et al. Data growth and its impact on the SCOP database: new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D419–D425. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva A, et al. SISYPHUS–structural alignments for proteins with non-trivial relationships. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;35:D253–D259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachar O, et al. A computer vision based technique for 3-d sequence-independent structural comparison of proteins. Protein Eng. 1993;6:279–288. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff A, et al. The CATH hierarchy revisited-structural divergence in domain superfamilies and the continuity of fold space. Structure. 2009;17:1051–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland RCG, et al. BioJava: an open-source framework for bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2096–2097. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J.Mol.Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jmol. Jmol: an open-source Java viewer for chemical structures in 3D. 2010 Available at: http://www.jmol.org/ (last accessed date October 20, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Needleman SB, Wunsch CD. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequences of two proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1970;48:443–453. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. Efficient detection of three-dimensional structural motifs in biological macromolecules by computer vision techniques. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:10495–10499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz AR, et al. MAMMOTH (matching molecular models obtained from theory): an automated method for model comparison. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2606–2621. doi: 10.1110/ps.0215902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Protein structure alignment by incremental combinatorial extension (CE) of the optimal path. Protein Eng. 1998;11:739–747. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.9.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippl MJ. On distance and similarity in fold space. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:872–873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippl MJ, Wiederstein M. A note on difficult structure alignment problems. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TF, Waterman MS. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1981;147:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova TA, Madden TL. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;174:247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeramalai M, et al. TOPS++FATCAT: fast flexible structural alignment using constraints derived from TOPS+ Strings Model. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:358. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Godzik A. Flexible structure alignment by chaining aligned fragment pairs allowing twists. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl. 2):II246–II255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Godzik A. FATCAT: a web server for flexible structure comparison and structure similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W582–W585. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Skolnick J. TM-align: a protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2302–2309. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]