Abstract

This was a preliminary investigation of the use of lithium to prevent lomustine-induced myelosuppression. Four 10 to 11 kg beagles received lomustine 20 to 30 mg, PO, q3wk, with cephalexin prophylaxis. Two dogs also received lithium, 150 to 300 mg, PO, q12h. Lithium blood concentrations fluctuated in and out of therapeutic interval. Lithium was discontinued in one dog in week 13, and in the other dog in week 38, due to toxicoses. All dogs developed grade 1 to 4 neutropenia after each lomustine treatment. In dogs receiving lomustine only, platelet concentrations decreased from 274 and 293 × 109/L in week 1, to 178 and 218 × 109/L in weeks 38 and 13, respectively. In dogs receiving lomustine and lithium, platelet concentrations decreased from 351 and 288 × 109/L in week 1, to 214 and 212 × 109/L, in weeks 36 and 13, respectively. Lithium did not prevent lomustine-induced myelosuppression and had important side-effects.

Résumé

Dans cette étude préliminaire sur l’utilisation du lithium pour prévenir la myélosuppression induite par la lomustine, 4 chiens beagle pesant 10 à 11 kg ont reçu 20 à 30 mg de lomustine, q3sem, en plus d’une prophylaxie au céphalexin. Deux chiens ont également reçu 150 à 300 mg de lithium PO, q12h. Les concentrations sanguines de lithium ont fluctué en-deçà et au-delà de l’intervalle thérapeutique. Compte tenu de toxicoses, le lithium a été discontinué chez un chien durant la semaine 13, et chez l’autre chien durant la semaine 38. Tous les chiens ont développé une neutropénie de grade 1 à 4 après chaque traitement à la lomustine. Chez les chiens recevant uniquement de la lomustine, les concentrations plaquettaires ont diminué de 274 et 293 × 109/L à la semaine 1, jusqu’à 178 et 218 × 109/L aux semaines 38 et 13, respectivement. Chez les chiens recevant de la lomustine et du lithium, les concentrations plaquettaires ont diminué de 351 et 288 × 109/L à la semaine 1, jusqu’à 214 et 212 × 109/L, aux semaines 36 et 13, respectivement. Le lithium n’a pas empêché la myélosuppression induite par la lomustine et causait également d’importants effets secondaires.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Lomustine is a cytotoxic drug of the nitrosourea class that is used in dogs to treat various neoplasms (1,2). The main acute dose-limiting side-effect is neutropenia, while a chronic dose-limiting side-effect is thrombocytopenia (1,2). Lithium (Li) is a psychomodulating drug that was noted to act as a hematopoietic stimulant (3). This prompted investigations into using Li as a treatment for chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression during the 1970s and 1980s, but attention then shifted to the hematopoietic cytokines (3). There has been a renewed interest in Li because, unlike hematopoietic cytokines, it is inexpensive and may be given orally (3,4). Lithium has been given to dogs with variable success in an effort to attenuate chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression due to cyclophosphamide, mechlorethamine, vinblastine, and carboplatin (5–7). Dexamethasone was recently reported to be ineffective in attenuating neutropenia caused by lomustine in dogs (1). Lithium attenuation of lomustine-induced myelosuppression has not been previously reported.

Study animals were 4 healthy male beagles ranging in age from 2 to 3 y and weighing from 10 to 11 kg. All procedures met the guidelines set by the Canadian Council on Animal Care (8), and were performed in accordance with the Animals for Research Act (Ontario, 1980), following approval by the Animal Care Committee, University of Guelph. The dogs were randomly allocated to non-Li (dogs 1 and 2) and Li (dogs 3 and 4) treatment groups. All dogs received lomustine (CeeNU; Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada, Montreal, Quebec), PO, q3wk. The first dosage was a standard therapeutic dosage of 30 mg (60 to 64 mg/m2) (2). This caused grade 4 neutropenia in all dogs (9), and sepsis in dogs 1 and 2, who recovered following treatment with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. The lomustine dosage was subsequently reduced to 20 mg (40 to 42 mg/m2), and cephalexin (Cephalexin; Novopharm, Toronto, Ontario) 250 mg (23 to 25 mg/kg), PO, q12h, was given for 10 d beginning 5 d after each treatment. Dogs 3 and 4 also received Li (Lithium carbonate; Pharmascience, Montreal, Quebec), PO, q12h, with intention to achieve Li concentrations within a therapeutic interval of 0.5 to 1.5 mmol/L (3,5–7). The first Li treatment was given at the same time as the first lomustine treatment. The initial Li dosage was 150 mg (14 to 15 mg/kg), but was increased to 300 mg (28 to 30 mg/kg) on week 5 in an effort to increase serum Li concentrations (6,10). On day 1, prior to any treatments, blood and urine samples were obtained for hemograms, serum biochemistries, and urinalyses (Animal Health Laboratory, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario), and serum Li concentrations (Homewood Health Centre, Guelph, Ontario) using a direct ion-selective electrode method (Cobas Integra 400, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Blood and urine samples were then obtained weekly immediately before the morning Li treatment for the same analyses. The first day of treatment was designated as day 1, week 1.

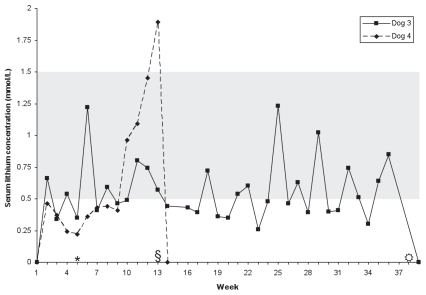

Lithium was undetectable at all times in dogs 1 and 2. Serum Li concentrations in dogs 3 and 4 are shown in Figure 1. In dog 3, mean [± standard deviation (s)] Li concentration was 0.57 (± 0.24) mmol/L. Of 34 values, 17 (50%) were > 0.5 mmol/L, the lower limit of therapeutic interval. The dog developed seizures beginning week 35. Additional serum Li concentrations were obtained whenever seizures occurred and were < 1 mmol/L. Lithium was discontinued at week 38, and no further seizures occurred during a follow-up period of 3 mo.

Figure 1.

Serum lithium concentrations in 2 dogs given lithium carbonate PO, q12h, for attenuation of lomustine-induced myelosuppression. Shaded area represents therapeutic interval.

* Change in dosage from 150 mg (14 to 15 mg/kg) q12h to 300 mg (28 to 30 mg/kg) q12h.

§ Lithium discontinued in dog 4.

Lithium discontinued in dog 3.

Lithium discontinued in dog 3.

In dog 4, mean Li (± s) concentration was 0.37 (± 0.09) mmol/L weeks 2 to 8, with all values below the therapeutic interval. The Li concentration then progressively increased, achieving 1.89 mmol/L on week 13 (day 85), at which time the dog had lethargy, inappetence, hypodipsia, vomiting, diarrhea, and a weight loss of 1.5 kg. Laboratory evaluation (reference intervals in brackets) on day 85 revealed a hematocrit of 0.74 L/L (0.39 to 0.56 L/L) and total protein of 84 g/L (55 to 74 g/L), but with serum urea and creatinine concentrations of 7.5 mmol/L (3.5 to 9.0 mmol/L) and 60 μmol/L (20 to 150 μmol/L), respectively. Serum electrolyte concentrations were: Na — 140 mmol/L (140 to 154 mmol/L); K — 5.7 mmol/L (3.8 to 5.4 mmol/L); Cl — 103 mmol/L (104 to 119 mmol/L); and total CO2 — 13 mmol/L (16 to 37 mmol/L), with a resulting anion gap of 30 mmol/L (13 to 24 mmol/L). Lithium was discontinued and the dog was treated with intravenous fluids. On days 87 to 88 the Li concentration decreased to 1.32 mmol/L and 0.72 mmol/L, respectively, and was undetectable 4 d later. Serum Na concentration transiently decreased to 138 mmol/L on day 88, at which time urinary fractional excretion (FENa) was 0.2% (reference interval < 1%). Within 1 week clinical signs resolved, and hematocrit, serum total protein, and electrolyte concentrations returned to within reference intervals. However, serum ALT and ALP activities, which were within reference intervals on days 85 to 88, increased to 3244 U/L (19 to 107 U/L) and 1260 U/L (22 to 143 U/L) on week 14 (day 92), respectively. No treatment was given, the dog remained clinically normal, and within 1 month liver enzyme activities had returned to within reference intervals.

Ptyalism developed during week 4 in dogs 3 and 4, and was particularly severe at the time of Li administration. Ptyalism resolved within 1 wk of discontinuing Li. Ptyalism did not occur in dogs 1 and 2.

Urine was well-concentrated, with specific gravity ranging from 1.035 to 1.039, in all dogs on day 1. In dogs 3 and 4, urine concentration decreased during week 4, and then ranged from hyposthenuria (specific gravity 1.000) to minimally concentrated urine (specific gravity 1.025). Urine became well-concentrated (urine specific gravity > 1.030) within 1 mo of discontinuing Li. In dogs 1 and 2, urine remained well-concentrated, with specific gravity ranging from 1.030 to > 1.050).

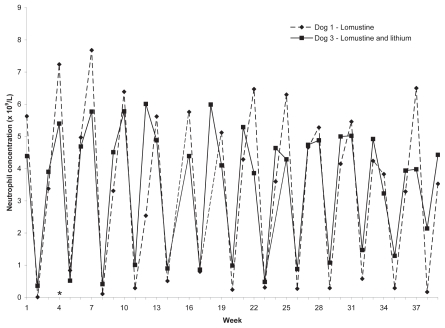

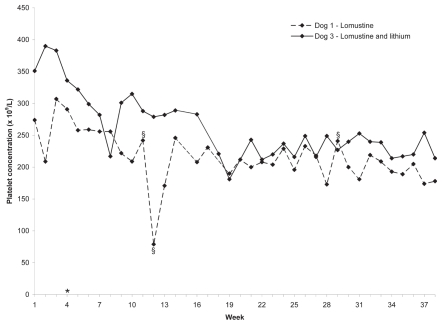

All dogs developed grade 1—4 neutropenia after each lomustine treatment (9). The neutrophil concentrations of dogs 1 and 3 are shown in Figure 2. The neutrophil concentrations of dogs 2 and 4 prior to withdrawal were similar. Platelet concentrations in dogs 1 and 3 decreased from 274 × 109/L and 351 × 109/L in week 1, to 178 × 109/L and 214 × 109/L, representing a decrease of 96 × 109/L and 137 × 109/L, respectively. Platelet concentrations in dogs 2 and 4 decreased from 293 × 109/L and 288 × 109/L in week 1, to 178 × 109/L and 212 × 109/L, representing a decrease of 75 × 109/L and 76 × 109/L, respectively. The platelet concentrations of dogs 1 and 3 are shown in Figure 3. The platelet concentrations of dogs 2 and 4 prior to withdrawal were similar.

Figure 2.

Neutrophil concentrations in 2 dogs given lomustine, PO, q3wk. Reference interval = 2.9 to 10.6 × 109/L. Labeled weeks on X-axis represent treatment weeks. Dog 3 was also given lithium carbonate, 150 (15 mg/kg), PO, q12h, weeks 1 to 4, and 300 mg (30 mg/kg), PO, q12h thereafter.

* Change in lomustine dosage from 30 mg (60 to 64 mg/m2) to 20 mg (40 to 42 mg/m2).

Figure 3.

Platelet concentrations in 2 dogs given lomustine, PO, q3wk. Reference interval = 117 to 418 × 109/L. Labeled weeks on X-axis represent treatment weeks. Dog 3 was also given lithium carbonate, 150 (15 mg/kg), PO, q12h, weeks 1 to 4, and 300 mg (30 mg/kg), PO, q12h thereafter.

* Change in lomustine dosage from 30 mg (60 to 64 mg/m2) to 20 mg (40 to 42 mg/m2).

§ Platelet clumps present on blood smear. The value of 79 × 109/L on week 12 was considered to be decreased due to platelet clumping.

This study was performed: 1) to obtain preliminary data characterizing myeloprotection by Li, in order to facilitate power calculation on which to base sample size and duration of treatment in future studies; and 2) to investigate potential toxic interactions between Li and lomustine. With respect to the first objective, other than the likely coincidence that dogs 1 and 2 developed sepsis after the first lomustine treatment, while dogs 3 and 4 did not, there was minimal evidence of attenuation of acute neutropenia. Because of withdrawals due to toxicoses, lomustine was not administered for a sufficient length of time to cause thrombocytopenia. However, Li treatment minimally (if at all) attenuated the decline in platelet concentrations within reference interval. Large treatment groups may be needed to demonstrate any Li platelet-sparing effect.

Several limitations must be considered in drawing this conclusion. First, there were only 2 dogs in each treatment group. Lithium has been shown to mildly stimulate granulopoiesis and thrombopoiesis in dogs, but, as in other species, the response is variable (3,7). It is possible that the 2 dogs receiving Li were poor responders and that 2 other dogs would have shown a Li effect.

Second, Li concentrations were not consistently within therapeutic interval. However, Li concentrations were usually > 0.3 mmol/L, the minimum concentration above which hematopoietic stimulation in many species is expected (3). Furthermore, Li concentrations of similar magnitude resulted in myeloprotection when given prior to cyclophosphamide (5). The optimal Li concentration for hematopoietic stimulation in dogs is not known. The initial Li dose was based on previous studies (5–7). Beagles have a higher dose requirement (10); therefore, in an effort to increase Li concentration, Li dose was increased week 5, but without consistent effect.

Third, Li was given daily. Optimal timing of treatment to ameliorate myelosuppression is not known. The current recommendation for hematopoietic cytokine therapy is to initiate treatment 24 h after a chemotherapy treatment because of concerns that induction of bone marrow progenitor cells into cycling and differentiation prior to chemotherapy will increase their susceptibility to injury and exacerbate myelosuppression (11). However, a “priming effect” has also been reported, where hematopoietic stimulation prior to cytotoxic therapy reduced the severity of acute myelosuppression (1,5,11,12). The mechanism of cumulative thrombocytopenia is not known, and in an effort to ensure Li action at any potentially critical periods before and after lomustine treatment, Li was given throughout the chemotherapy cycle.

A fourth limitation is that cephalexin was given to prevent sepsis and resultant hematopoietic stimulation (13). It is possible that cephalexin interfered with Li action.

Several toxicoses were observed. Ptyalism may have been a sign of nausea, but it is also a side-effect of Li in humans (14). Decreased urine specific gravity was consistent with Li-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, which is common in humans and was noted in 2 dogs with chronic Li intoxication (15,16).

Lethargy and inappetence occurred in dog 4 when the Li concentration rose above therapeutic interval, and laboratory evaluation revealed hemoconcentration, and electrolyte and acid-base disturbances. Hemoconcentration was likely a result of hypodipsia and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus; the absence of azotemia was surprising, but was also noted in the previous report of Li intoxication (16). The absence of hypernatremia in the presence of a presumptively large free-water deficit was attributed to Li-induced natriuresis (15,16). This was not confirmed by FENa, but Li had been withdrawn for 3 d when FENa was measured. Transient hyponatremia was attributed to free water intake once the dog began drinking. Clinical signs of Li toxicosis were not reported in a previous study of hematopoietic stimulation in dogs when toxic Li concentrations were achieved (6). This is likely because Li was given for < 3 wk — Li accumulates in tissues and serum Li concentrations above therapeutic interval are more likely to cause signs of toxicosis with chronic therapy (17).

Lithium was implicated as the cause of seizures in dog 3, but these were not associated with a toxic serum Li concentration. Similarly, in the report of chronic Li intoxication in dogs, seizures were associated with a Li concentration of 1.1 mmol/L, and Li-induced seizures may also occur in humans with therapeutic Li concentrations (16,18).

Marked elevations in liver enzymes occurred in dog 4. Hepatic injury due to Li is not common in humans, although Li is hepatotoxic to rats and drug metabolizing enzyme induction may occur in dogs (19,20). Elevations in liver enzymes in dog 4 may have been due to direct Li hepatotoxicity, hepatic hypoxia due to volume contraction, or an interaction with lomustine, which may be hepatotoxic (2).

In conclusion, the preliminary evidence is 1) that Li at the dosages and schedule used in this study may not have a marked effect in preventing acute neutropenia or cumulative thrombocytopenia in dogs given lomustine; and 2) that long-term administration of Li may result in undesirable side-effects. This study reinforced the importance of measuring serum Li concentrations when using the drug.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Ontario Veterinary College Pet Trust. The assistance of Amanda Hathway with animal care is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 25th Annual Veterinary Cancer Society Conference, Huntington Beach, California, USA, November, 2005.

References

- 1.Intile JL, Rassnick KM, Bailey DB, et al. Evaluation of dexamethasone as a chemoprotectant for CCNU-induced bone marrow suppression in dogs. Vet Comp Oncol. 2009;7:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2008.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristal O, Rassnick KM, Gliatto JM, et al. Hepatotoxicity associated with CCNU (lomustine) chemotherapy in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:75–80. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2004)18<75:hawclc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Focosi D, Azzara A, Kast RE, Carulli G, Petrini M. Lithium and hematology: Established and proposed uses. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:20–28. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0608388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hager ED, Dziambor H, Hohmann D, Winkler P, Strama H. Effects of lithium on thrombopoiesis in patients with low platelet cell counts following chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2001;83:139–148. doi: 10.1385/BTER:83:2:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossof AH, Fehir KM, Budd HS, Murthy A, Economou SG. Lithium carbonate enhances granulopoiesis and attenuates cyclophosphamide-induced injury in the dog. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1980;127:155–166. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-0259-0_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenthal RC. PhD dissertation. Urbana-Champaign, Illinois: Univ. of Illinois; 1985. Lithium carbonate as a protectant against chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leclerc A, Abrams-Ogg ACG, Kruth S, Bienzle D. The effect of lithium carbonate on carboplatin-induced thrombocytopenia in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2010;71:555–563. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.71.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Council on Animal Care. Guide to the Care and use of Experimental Animals. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Vol. 2. Ottawa, Ontario: 1993. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veterinary Co-operative Oncology Group. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (VCOG-CTCAE) following chemotherapy or biological antineoplastic therapy in dogs and cats v1.0. Vet Comp Oncol. 2004;2:195–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5810.2004.0053b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenthal RC, Koritz GD. Pharmacokinetics of lithium in beagles. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 1989;12:330–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.1989.tb00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein SH, Fay JP, Christiansen NP, et al. Sequential inter-leukin-3 and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor prior to and following high-dose etoposide and cyclophosphamide: A phase I/II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:1519–1526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnke RM, Abernathy RS. Accelerated marrow recovery following total-body irradiation after treatment with vincristine, lithium or combined vincristine-lithium. Int J Cell Cloning. 1991;9:78–88. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530090110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zakynthinos SG, Papanikolaou S, Theodoridis T, et al. Sepsis severity is the major determinant of circulating thrombopoietin levels in septic patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1004–1010. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000121433.61546.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donaldson SR. Sialorrhea as a side effect of lithium: A case report. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1350–1351. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.10.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunfeld JP, Rossier BC. Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:270–276. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies NL. Lithium toxicity in two dogs. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1991;62:140–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen KP, Shen WW, Lu ML. Implication of serum concentration monitoring in patients with lithium intoxication. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grueneberger EC, Maria Rountree E, Baron Short E, Kahn DA. Neurotoxicity with therapeutic lithium levels: A case report. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15:60–63. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000344921.36157.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chadha VD, Bhalla P, Dhawan DK. Zinc modulates lithium-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Liver Int. 2008;28:558–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali B, Spencer HW, Auyong TK, Parmar SS. Selective induction of hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes by lithium treatment in dogs. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1975;27:131–132. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1975.tb09422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]