Abstract

Background: OVA-301 is a large randomized trial that showed superiority of trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) over PLD alone in relapsed ovarian cancer. The optimal management of patients with partially platinum-sensitive relapse [6–12 months platinum-free interval (PFI)] is unclear.

Patients and methods: Within OVA-301, we therefore now report on the outcomes for the 214 cases in this subgroup.

Results: Trabectedin/PLD resulted in a 35% risk reduction of disease progression (DP) or death [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.65, 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.45–0.92; P = 0.0152; median progression-free survival (PFS) 7.4 versus 5.5 months], and a significant 41% decrease in the risk of death (HR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.43–0.82; P = 0.0015; median survival 23.0 versus 17.1 months). The safety of trabectedin/PLD in this subset mimicked that of the overall population. Similar proportions of patients received subsequent therapy in each arm (76% versus 77%), although patients in the trabectedin/PLD arm had a slightly lower proportion of further platinum (49% versus 55%). Importantly, patients in the trabectedin/PLD arm survived significantly longer after subsequent platinum (HR = 0.63; P = 0.0357; median 13.3 versus 9.8 months).

Conclusion: This hypothesis-generating analysis demonstrates that superior benefits with trabectedin/PLD in terms of PFS and survival in the overall population appear particularly enhanced in patients with partially sensitive disease (PFI 6–12 months).

Keywords: pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, platinum-free interval, relapsed ovarian cancer, trabectedin

introduction

Trabectedin is a marine-derived antineoplastic agent, initially isolated from the tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata and currently produced synthetically. It was first approved as a single agent in the European Union in 2007 and, subsequently, in many other countries worldwide for patients with soft tissue sarcoma after failure of standard-of-care chemotherapies. Trabectedin showed encouraging single-agent activity in several phase II trials in relapsed ovarian cancer [1–3]. Trabectedin plus doxorubicin showed synergy in vitro [4, 5] and, in a phase I trial, trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD, CentoCor Ortho Biotech Products L.P., Raritan, NJ) was well tolerated and provided clinical benefit at therapeutic doses of both drugs in pretreated patients with diverse tumor types including ovarian cancer [6]. A randomized, multicenter, phase III trial (OVA-301) evaluated the combination of trabectedin plus PLD versus PLD alone in relapsed ovarian cancer, with progression-free survival (PFS) by independent radiology review as the primary end point [7, 8]. When combined with PLD, trabectedin improved PFS over PLD alone, with a 21% risk reduction of disease progression (DP) or death [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.79; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.65–0.96; P = 0.0190; median 7.3 versus 5.8 months) and adequate tolerability. In the platinum-sensitive stratum [platinum-free interval (PFI) ≥ 6 months], the risk reduction of DP or death was 27% (HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56–0.95; P = 0.0170; median PFS 9.2 versus 7.5 months). A protocol-specified interim analysis of overall survival (OS) was conducted with 300 events (versus 520 required for the final OS analysis) showing a 15% reduction in the risk of death with the combination (HR = 0.85; P = 0.1506). Based mainly on these results, the European Union Commission granted marketing authorization for trabectedin combined with PLD for the treatment of patients with relapsed, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer in October 2009 [9].

The effectiveness of platinum re-treatment in relapsed ovarian cancer is highly correlated with the PFI. A PFI ≥ 6 months predicts platinum sensitivity, but within this group, a PFI of 6–12 months is considered to indicate a ‘partially’ platinum-sensitive disease [10]. Platinum-based therapy is generally accepted as standard in patients with PFI > 12 months, with response rates ranging from 30% to 60%. Less consensus exists as to the benefits of platinum rechallenge in the partially platinum-sensitive subgroup, where response rates to further platinum are in the 25%–30% range [11]. Preclinical and clinical data [12–15] indicate that, in relapsed ovarian cancer, the artificial expansion of PFI with an intervening nonplatinum therapy may be beneficial possibly by reversing platinum resistance, which may be of particular interest to patients with partially platinum-sensitive disease (PFI 6–12 months).

Furthermore, clinically significant toxicities such as hypersensitivity reactions and residual neurotoxicity are common and may hamper re-administration of platinum-based chemotherapy, underscoring the need for an efficacious nonplatinum regimen [16, 17], particularly in the partially platinum-sensitive population [10, 18]. Few phase III studies of combination regimens versus platinum monotherapy or comparing various nonplatinum single agents have reported clinical outcomes in partially platinum-sensitive patients [19].

OVA-301 [7, 8] has been one of the largest conducted randomized trials in relapsed ovarian cancer after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy. One-third of the 672 randomized patients in OVA-301 (n = 214, 32%) had a PFI from 6 to 12 months. The current post hoc, exploratory, hypothesis-generating analysis provides a detailed assessment of results for the partially platinum-sensitive population, including a description of subsequent therapies administered to these patients.

patients and methods

study design

Full details of OVA-301 trial have been reported elsewhere [8]. Briefly, OVA-301 was an open-label, multicenter, randomized, phase III clinical trial designed to investigate the efficacy and safety of the combination of PLD 30 mg/m2 followed by trabectedin 1.1 mg/m2 every 3 weeks compared with PLD 50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks. Eligible patients were women ≥18 years old with histologically proven epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinoma in relapse or progression after one platinum-based chemotherapy regimen. Patients with platinum-resistant (PFI <6 months) or platinum-sensitive disease (PFI ≥ 6 months) were eligible. The trial was stratified based on platinum sensitivity (platinum resistant versus platinum sensitive) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0–1 versus 2). The primary end point was PFS by independent radiology assessment. Secondary analyses of PFS were based on independent oncologist and investigator’s assessments. The trial was also powered for OS. From April 2005 until May 2007, a total of 672 patients were randomized: 335 (PLD) and 337 (trabectedin/PLD). The final PFS analysis was conducted with 389 PFS events assessed by independent radiology in patients with radiologically measurable disease with a predetermined data cut-off (15 May 2008) [8]. This report focuses on the outcomes in the partially platinum-sensitive patients subset (PFI 6–12 months), with updated OS data generated at the request of the regulatory authorities with one additional year of follow-up (data cut-off, 31 May 2009) [9]. A summarized description of subsequent therapies is provided.

statistical methods

Efficacy analysis populations include all randomized (intent-to-treat) and all measurable (all randomized patients with radiologically measurable disease) patients. The primary analysis of PFS was conducted in the ‘all measurable’ dataset by independent radiology review. Unless otherwise specified, all other efficacy analyses were performed on the all randomized analysis set. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and arms were compared by the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare treatment arms after adjusting by baseline prognostic factors.

results

The most representative baseline characteristics for the partially platinum-sensitive subset of patients (n = 214) are given in Table 1. They did not differ from those in the overall study population [8].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the partially platinum-sensitive subset of patients (OVA-301 study)

| Arm |

P valuea | ||

| PLD | Trabectedin/PLD | ||

| No. of patients | 91 | 123 | |

| Age, years | |||

| Median | 56 | 57 | 0.9635 |

| Range | 37–82 | 40–76 | |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 84 | 83 | 1.0000 |

| Other | 16 | 17 | |

| ECOG PS (%) | |||

| 0 | 65 | 70 | 0.4617 |

| >0 | 35 | 30 | |

| Platinum-free interval, months | |||

| Medianb | 8.3 | 7.9 | 0.2186 |

| Histology (%) | |||

| Papillary/serous | 71 | 70 | 0.8798 |

| Other | 29 | 29 | |

| Prior lung/liver metastases (%) | 35 | 42 | 0.3956 |

| Prior taxane (%) | 81 | 76 | 0.4061 |

Patient characteristics were well balanced and not different from those of the overall population.

Range was 6–12 months.

Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney for continuous variables.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; PS, performance status.

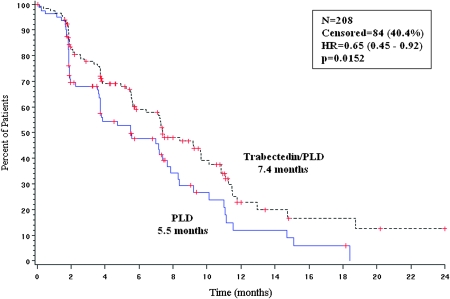

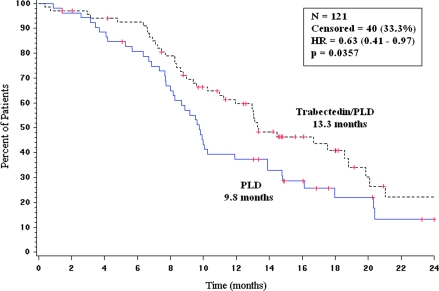

progression-free survival

Results of the primary end point (PFS by independent radiology review) in the partially platinum-sensitive subset of patients are shown in Figure 1. The HR was 0.65 (95% CI, 0.45–0.92), indicating a 35% risk reduction of DP or death significantly favoring the trabectedin/PLD combination (P = 0.0152). Median PFS was 7.4 months in the trabectedin/PLD arm versus 5.5 months in the PLD arm. When compared with PFS results for other subsets of patients according to PFI (Table 2), the largest benefit with trabectedin/PLD treatment was obtained in the partially platinum-sensitive subset.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival for the partially platinum-sensitive population (OVA-301 study). independent radiology review of all measurable patients (primary end point). HR, hazard ratio; N, number of patients; P, log-rank test P value; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

Table 2.

Progression-free survival results according to platinum-free interval: independent radiology review (primary analysis) and independent oncology review (secondary analysis) (OVA-301 study)

|

The secondary, supportive analysis of PFS by independent oncology review showed an HR of 0.54 (95% CI, 0.39–0.76), i.e. a statistically significant 46% risk reduction of DP or death (P = 0.0002) with the trabectedin/PLD combination (Table 2).

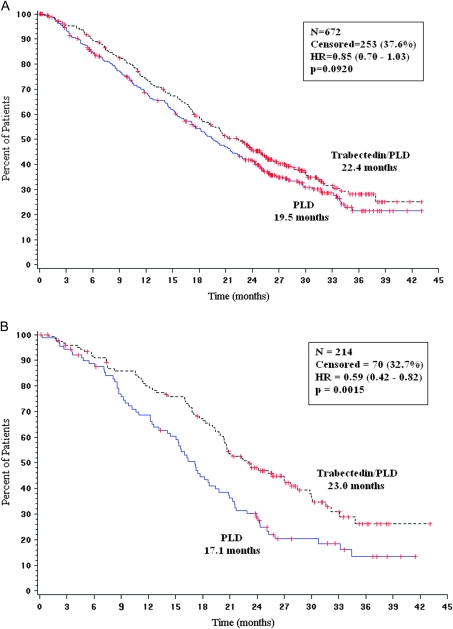

overall survival

At the 31 May 2009 cut-off, a total of 419 of the 672 randomized overall population had died (n = 215, PLD; n = 204, trabectedin/PLD), which represents 81% of the 520 death events required for the final OS analysis per protocol. In this updated analysis, trabectedin/PLD combination resulted in a 15% decrease in the risk of death compared with PLD alone (HR = 0.85, 95% CI, 0.70–1.03; P = 0.092). Median OS was 22.4 months (95% CI, 19.4–25.1) in the trabectedin/PLD arm versus 19.5 months (95% CI, 17.4–22.1) in the PLD arm (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Updated interim analysis of overall survival for OVA-301 study (cut-off, 31 May 2009). (A) All randomized patients. (B) Partially platinum-sensitive population. HR, hazard ratio; N, number of patients; P, log-rank test P value; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

In the partially platinum-sensitive subset of patients, trabectedin/PLD induced a significant 41% decrease in the risk of death compared with PLD alone (HR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.43–0.82; P = 0.0015). Median OS was 23.0 months in the trabectedin/PLD arm versus 17.1 months in the PLD arm (Figure 2B).

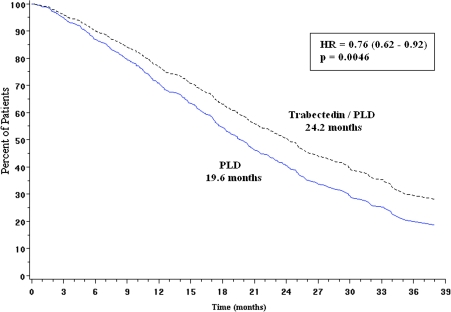

A multivariate analysis in the overall population showed a significantly longer survival with trabectedin/PLD after covariate adjustment for prognostic factors, with an 18% risk reduction of death (HR = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.67–0.99; P = 0.041; Table 3). In this multivariate analysis, one of the most relevant prognostic factors was PFI (P < 0.0001). Because PFI was significantly unbalanced favoring the PLD arm (mean PFI 13.3 months in PLD arm versus 10.6 months in the trabectedin/PLD arm; P = 0.009), a Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare OS in the two arms adjusting by PFI. This analysis showed a statistically significant 24% risk reduction of death (HR = 0.76, 95% CI, 0.62–0.92; P = 0.0046) for patients randomized to the trabectedin combination (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of overall survival for prognostic factors (OVA-301 study; overall population; updated analysis, cut-off, 31 May 2009)

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% hazard ratio confidence limits | P value | |

| Treatment group | 0.816 | 0.672 | 0.991 | 0.0407 |

| Prior taxane | 1.355 | 1.045 | 1.757 | 0.0217 |

| ECOG PS | 1.562 | 1.275 | 1.914 | <0.0001 |

| Race | 1.159 | 0.920 | 1.461 | 0.2112 |

| PFI | 0.946 | 0.932 | 0.959 | <0.0001 |

| CA 125 | 1.191 | 0.915 | 1.551 | 0.1934 |

| Age (years) | 1.006 | 0.996 | 1.016 | 0.2329 |

| Liver/lung metastases | 1.412 | 1.160 | 1.719 | 0.0006 |

| Ascites at baseline | 2.124 | 1.737 | 2.596 | <0.0001 |

| Bulky disease | 1.601 | 1.310 | 1.956 | <0.0001 |

Groups for analysis: treatment arm (PLD versus trabectedin + PLD); prior taxane (no versus yes); ECOG PS (0 versus >0); race (white versus others); PFI and age (continuous variables); CA 125 (<2x ULN versus ≥2x ULN); liver/lung metastases (no versus yes); ascites (no versus yes); bulky disease (no versus yes).

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PFI, platinum-free interval; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; PS, performance status; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Figure 3.

Overall survival adjusted by continuous platinum-free interval (OVA-301 study, cut-off, 31 May 2009). HR, hazard ratio; P, Cox regression P value; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

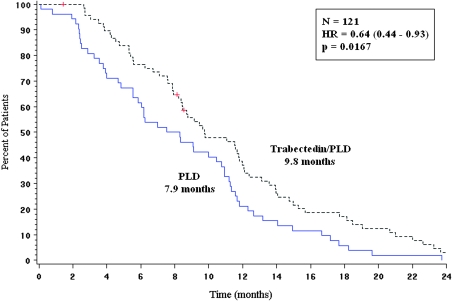

subsequent therapy

In OVA-301 study, similar proportions of patients received subsequent therapy in each treatment arm (77% versus 76%; P = 0.8195). The proportion of further platinum-based therapies in the trabectedin/PLD arm was slightly lower than in the PLD arm: 49% versus 55%, P = 0.1236 (56% versus 57%, p=0.8900 in the PFI 6-12 subset).

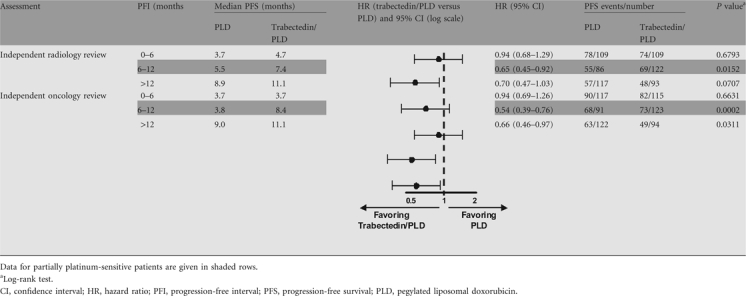

In the subset of patients with partially platinum-sensitive disease, time from randomization to subsequent platinum was significantly longer (HR = 0.64; P = 0.0167; median 9.8 versus 7.9 months) for patients in the trabectedin/PLD combination arm (Figure 4). Furthermore, patients randomly assigned to the trabectedin/PLD combination experienced significantly longer survival counted from the initiation of subsequent platinum-based therapy: HR = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41–0.97; P = 0.0357; median 13.3 months in the trabectedin + PLD arm versus 9.8 months in the PLD arm (Figure 5). A detailed description of subsequent therapies in this trial is reported separately [20].

Figure 4.

Time from randomization to subsequent platinum-based therapy in the partially platinum-sensitive subpopulation (OVA-301 study, PFI 6- to 12-month subset, n = 121). HR, hazard ratio; N, number of patients; P, log-rank test P value; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

Figure 5.

Overall survival from subsequent platinum-based therapy in the partially platinum-sensitive population (OVA-301 study, PFI 6- to 12-month subset; n = 121). Censored: PLD arm (21%); trabectedin/PLD arm (42%). HR, hazard ratio; N, number of patients; P, log-rank test P value; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

drug exposure and safety

Exposure to treatment in the PFI 6–12 months patient subset was similar to that in the overall patient population [8]. The median number of cycles received was 5 (range, 1–21) in the PLD arm and 6 (range, 1–15) in the trabectedin/PLD arm; 24% and 40% of patients received seven or more cycles. The safety profile was not different from that in the overall population (Table 4). Notably, when compared with single-agent PLD, the trabectedin/PLD combination induced a higher incidence of transient neutropenia and transaminase elevations and a lower incidence of symptomatic events, namely hand and foot syndrome and mucositis. Exposure to previous taxanes did not result in a different liver function test pattern. Unlike established platinum and taxane-based regimens, trabectedin/PLD was associated with greatly diminished incidence of neuropathy and alopecia, as well as lack of end organ, cumulative toxic effects. The addition of trabectedin to PLD did not result in a decrement in overall health status, as assessed by patient reported outcomes.

Table 4.

Main treatment-related adverse events reported in partially platinum-sensitive patients and in the overall population (OVA-301 study)

| Partially platinum-sensitive patients (PFI 6–12 months) |

All patients |

|||||||||||

| PLD (n = 91) |

Trabectedin/PLD (n = 123) |

PLD (n = 330) |

Trabectedin/PLD (n = 333) |

|||||||||

| Grade |

Grade |

Grade |

Grade |

|||||||||

| Any | 3 | 4 | Any | 3 | 4 | Any | 3 | 4 | Any | 3 | 4 | |

| Hematological | ||||||||||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | <1 | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| Neutropenia | 72 | 23 | 9 | 92 | 34 | 39 | 74 | 20 | 10 | 92 | 30 | 42 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 30 | 2 | – | 68 | 8 | 9 | 27 | 2 | 2 | 64 | 12 | 11 |

| Nonhematological | ||||||||||||

| Alopecia | 19 | – | – | 15 | – | – | 13 | – | – | 12 | – | – |

| ALT increase | 36 | 1 | – | 98 | 46 | 5 | 36 | 2 | – | 96 | 46 | 5 |

| Fatigue | 33 | 3 | – | 48 | 8 | 1 | 30 | 2 | <1 | 42 | 6 | <1 |

| Mucosal inflammation | 21 | 7 | – | 11 | 2 | – | 19 | 6 | – | 11 | 2 | – |

| Nausea | 39 | 4 | – | 74 | 11 | – | 38 | 2 | – | 71 | 9 | – |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 2 | – | – | 3 | – | – | 2 | – | – | 4 | – | – |

| PPD syndrome | 47 | 17 | – | 29 | 5 | – | 54 | 18 | 1 | 24 | 4 | – |

| Stomatitis | 31 | 4 | – | 19 | 2 | – | 31 | 5 | <1 | 19 | 1 | – |

| Vomiting | 27 | 2 | – | 47 | 8 | 1 | 24 | 2 | – | 52 | 10 | <1 |

Data shown are % of patients. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; PPD, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia.

discussion

OVA-301 was a large (n = 672), rigorously conducted randomized trial evaluating the combination of trabectedin plus PLD versus PLD alone in patients with relapsed ovarian cancer. The trial met its primary end point, demonstrating significantly superior PFS with the combination confirmed by both independent radiology and independent oncology reviews, and with a positive trend in the interim analysis of OS [7, 8]. Benefits appeared more evident in the platinum-sensitive stratum (PFI ≥ 6 months), where the risk reduction of DP or death was 27% (HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56–0.95; P = 0.0170; median PFS 9.2 versus 7.5 months) [8].

updated survival analysis in the overall population

The updated interim analysis of survival, with 419 death events (38% censored data) and an additional year of follow-up, continues to show a favorable trend for trabectedin/PLD arm, with an identical 15% reduction in the risk of death than that shown 1 year earlier [8]. Nevertheless, with a larger number of death events (419 versus 300) in this more mature dataset, a more evident separation of the survival curves is shown, the 95% CI around the HR is narrower, and the P value is now 0.092 (versus 0.151 previously; Figure 2A). Median OS was almost identical at 19.5 months in the PLD arm but is now improved to 22.4 months in the trabectedin/PLD arm, i.e. a nearly 3-month prolongation in median survival for patients randomly assigned to the combination arm. Therefore, the updated interim survival results confirm and strengthen those reported previously in a more mature dataset with 1 year longer follow-up.

A relevant finding emerged when OS data for the overall population was adjusted for the existing PFI imbalance between treatment arms. When corrected by such imbalance, the Cox proportional hazards model showed a statistically significant 24% risk reduction for death (P = 0.0046) in patients randomly assigned to the trabectedin/PLD regimen in the updated dataset for the overall population. Pending the final OS analysis to be conducted once the required 520 events are reached, the current data suggest that trabectedin in combination with PLD may prolong survival over PLD alone in the overall population of patients with relapsed ovarian cancer.

outcomes with trabectedin/PLD in patients with partially platinum-sensitive disease

Patients whose ovarian cancer responds to first-line platinum-based therapy and relapse between 6 and 12 months after completion of this initial chemotherapy represent a subpopulation with a dismal outcome (1-year median survival) [21] for whom there is a high need for new effective treatment options, including nonplatinum alternatives. Single-agent PLD is often recommended in these patients as indicated by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (http://www.nice.org.uk) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines (http://www.nccn.org). As expected, previous results of a multivariate analysis in OVA-301 showed PFI as an independent predictor of outcomes for both PFS and OS [8]. The data in the hypothesis-generating analyses reported here show that benefits with trabectedin/PLD combination appeared more pronounced in patients with partially platinum-sensitive disease, with a 35%–46% risk reduction of DP or death versus PLD alone by independent radiology and independent oncology review, respectively, compared with the corresponding 21%–28% figures in the overall population [8].

Notably, a 41% reduction in the risk of death was obtained for the subset of patients with partially platinum-sensitive disease randomized to the trabectedin combination (P = 0.0015), with median OS extended by 6 months versus PLD alone. Therefore, the survival benefits with the trabectedin/PLD regimen appeared markedly enhanced in patients with partially platinum-sensitive disease.

The positive trend toward a survival advantage with the trabectedin/PLD combination versus PLD alone observed in the interim analysis of the overall population, as well as in the PFI 6- to 12-month subset, appears unlikely due to the effects of subsequent therapies received by the patients after discontinuing study medication in this trial. Roughly the same proportion of patients in each arm received subsequent therapy, and the patients treated with trabectedin/PLD received a slightly lower proportion of further platinum-based therapies compared with those treated with PLD alone.

The administration of subsequent platinum was significantly delayed for patients in the trabectedin/PLD combination. Such PFI extension may represent an added benefit for these patients, at the very least by allowing extra time to recover from toxic effects of their front-line platinum-based therapy. Furthermore, patients randomly assigned to the trabectedin/PLD combination experienced significantly longer survival counted from the initiation of subsequent platinum. The current hypothesis-generating analyses suggest that the enhanced survival benefits with trabectedin/PLD over single-agent PLD in OVA-301, particularly in patients with partially platinum-sensitive disease, may be due to an extension of the PFI. This hypothesis should be confirmed in prospective randomized trials.

No new or unexpected safety findings were seen with trabectedin/PLD combination in the PFI 6-12 subpopulation relative to those observed for the overall population [8]; thus, the toxic effects of this combined chemotherapy are predictable and manageable. This is consistent with the lack of pharmacokinetic interactions between these two drugs found in previous studies with PLD [6] or nonliposomal doxorubicin [22, 23]. Therefore, this safety profile together with current PFS and interim OS results provide evidence for a highly favorable benefit/risk outcome in the partially platinum-sensitive subpopulation, in which there is a high unmet need for new treatment options.

relevance of OVA-301 results within the context of relapsed ovarian cancer

Results for the partially platinum-sensitive population in OVA-301 are given in Table 5 in context with results of other phase III randomized trials in relapsed, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer [24–26]. OVA-301 [8] included patients with platinum-resistant disease (35% of patients), whereas the other trials solely included patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. The CALYPSO trial conducted by the GINECO group within the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup, compared carboplatin/PLD versus carboplatin/paclitaxel, and reported separate results for the partially platinum-sensitive population [27]. In this subset, better PFS outcomes were also obtained with carboplatin/PLD versus carboplatin/paclitaxel (27% risk reduction of DP or death; median PFS 9.4 versus 8.8 months). It is to be stressed that the PFS analyses in OVA-301 used a very rigorous methodology and strict scrutiny. Data assessed by an independent radiology panel blinded to treatment arm assignment in patients with measurable disease were the basis of the primary analysis. In addition, as a sensitivity analysis, an independent oncology review, also blinded to treatment allocation, combined the results of the radiology review with clinical outcomes in evaluable disease.

Table 5.

Results of phase III randomized clinical trials evaluating combination regimens for second-line therapy of platinum-sensitive patients

| Treatment | Paclitaxel/carboplatin | Gemcitabine/carboplatin | PLD/carboplatin | PLD/trabectedin | |

| Control | Carboplatin | Carboplatin | Carboplatin/paclitaxel | PLD | |

| Study | Parmar et al. [24] | Pfisterer et al. [25] | Pujade-Lauraine et al. [26], Vasey et al. [27] | Monk et al. [8] | |

| Number of patientsa | 392 | 178 | 466 | 337b | |

| Prior taxane (%) | 40 | 71 | 100 | 80 | |

| % PFI 6–12 monthsc | 23d | 40 | 35 | 37e | |

| Efficacy results in total population/patients with PFI 6–12 months | |||||

| Primary end point | OS | PFS | PFS | PFS (independent radiology review)f | PFS (independent oncology review)g |

| PFS, median (months) | 13.0/NA | 8.6/NAi | 11.3/9.4 | 7.3/7.4 | 7.4/8.4 |

| Risk reduction of DP or death versus control | ↓24%/NA | ↓28%/NA | ↓18%/↓27% | ↓21%/↓35% | ↓28%/↓46% |

| OS, median (months) | 29.0/NA | 18/NA | NA | 22h/23 | |

| Risk reduction of death versus control | ↓18%/NA | ↓4%/NA | NA | ↓15%h/↓41% | |

| Added toxicity versus control | Myelotoxicity, neurotoxicity | Myelotoxicity | Hand and foot syndrome, mucositis | Myelotoxicity, LFTs | |

For randomized controlled trials, number of patients in the combination arm.

337 patients was the overall population in trabectedin/PLD arm, of whom 218 had platinum-sensitive disease.

Partially platinum-sensitive.

PFI ≤ 12 months.

OVA-301 included 35% of patients with platinum-resistant disease (PFI < 6 months).

Primary analysis.

Secondary supportive analysis.

Current updated survival analysis.

iEfficacy (PFS) outcomes not based on independent review.

LFT, liver function tests; NA, not available; OS, overall survival; DP, disease progression; PFI, platinum-free interval; PFS, progression-free survival; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

OVA-301 confirmed the superiority of trabectedin/PLD combination compared with PLD alone in relapsed ovarian cancer [7], and the current analysis strongly suggests that the greatest benefits in PFS and survival are obtained among patients with partially platinum-sensitive disease. Since most women with relapsed ovarian cancer will eventually experience DP and will die of their disease, both safety and efficacy are important in assessing the role of a novel combination in this disease setting. The use of a nonplatinum-based combination may allow treatment for patients having not yet recovered from previous platinum toxicity (e.g. residual neurotoxicity or hypersensitivity) [28, 29] and, as suggested in the partially platinum-sensitive subpopulation of OVA-301, may provide a further survival advantage after the reintroduction of subsequent platinum. This might be due to a reversal of the partial resistance pattern [15], a hypothesis that warrants a prospective trial. Furthermore, as trabectedin has been advocated as an interesting agent to utilize in patients with carboplatin hypersensitivity as a `platinum substitute,’ this raises some interesting questions related to biology and clinical behavior, which require a randomized study (with surrogate and translational endpoints) comparing both drugs in the same population.

The trabectedin/PLD combination provides a new option for platinum-sensitive patients with relapsed ovarian cancer after failure of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Because re-treatment with platinum-based therapy remains a viable option in this setting, further studies comparing trabectedin/PLD with a platinum-containing combination are warranted. Thus, a large randomized intergroup trial is currently in late stages of preparation to evaluate OS in patients with partially platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer treated initially with trabectedin/PLD (and followed by platinum-based therapy upon relapse) versus carboplatin/PLD, the regimen recently evaluated in the CALYPSO trial [26, 27].

In conclusion, the randomized phase III trial OVA-301 demonstrates that trabectedin combined with PLD induced enhanced benefits in terms of PFS and survival, and thus represents a safe and effective nonplatinum, nontaxane alternative for the treatment of patients with relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. The results of the hypothesis-generating analyses reported here in the important subset of patients with partially sensitive disease (PFI 6–12 months) strongly suggest an enhanced benefit of trabectedin/PLD regimen in this subpopulation. Trabectedin in combination with PLD may be administered to relapsed ovarian cancer patients while they recover from prior platinum-related toxic effects, and prolongation of PFI could help to improve response to—and survival after–subsequent platinum-based therapy.

funding

Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C.; Pharma Mar.

disclosure

A.P., S.B.K. and N.C. were compensated as consultants or advisors. C.L, J.G. and V.A. are employees in PharmaMar and are stock owners. T.P. and Y.C.P. are employees in Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C. B.J.M. received funding for research and honoraria.

References

- 1.Sessa C, De Braud F, Perotti A, et al. Trabectedin for women with ovarian carcinoma after treatment with platinum and taxanes fails. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1867–1874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krasner CN, McMeekin DS, Chan S, et al. A phase II study of trabectedin single agent in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer previously treated with platinum-based regimens. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1618–1624. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Campo JM, Roszak A, Bidzinski M, et al. Phase II randomized study of trabectedin given as two different every 3 weeks dose schedules (1.5 mg/m2 24 h or 1.3 mg/m2 3 h) to patients with relapsed, platinum-sensitive, advanced ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1794–1802. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi N, Li WW, Banerjee D, et al. Sequence-dependent enhancement of cytotoxicity produced by ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with doxorubicin or paclitaxel in soft tissue sarcoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3251–3257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meco D, Colombo T, Ubezio P, et al. Effective combination of ET-743 and doxorubicin in sarcoma: preclinical studies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Mehren M, Schilder RJ, Cheng JD, et al. A phase I study of the safety and pharmacokinetics of trabectedin in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with advanced malignancies. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1802–1809. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monk BJ, Herzog T, Kaye S, et al. A randomized phase III study of trabectedin with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) versus PLD in relapsed, recurrent ovarian cancer (OC) Ann Oncol. 2008;19:viii1–viii4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.034. LBA4; doi:10.1093/annonc/mdn1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monk BJ, Herzog TJ, Kaye S, et al. Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3107–3114. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Medicines Agency (EMA) Assessment report for Yondelis. International non-proprietary name/Common name: trabectedin Procedure. No.EMEA/H/C/000773/II/0008. 2009. http://www.ema.europa.eu/humandocs/PDFs/EPAR/yondelis/EMEA-H-773-II-08-AR.pdf. (18 March 2010, date last accessed). EMEA/640507/2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaye S. Management of partially platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. Eur J Canc Suppl. 2008;6:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackledge G, Lawton F, Redman C, Kelly K. Response of patients in phase II studies of chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: implications for patient treatment and the design of phase II trials. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:650–653. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horowitz NS, Hua J, Gibb RK, et al. The role of topotecan for extending the platinum-free interval in recurrent ovarian cancer: an in vitro model. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bookman MA. Extending the platinum-free interval in recurrent ovarian cancer: the role of topotecan in second-line chemotherapy. Oncologist. 1999;4:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.See HT, Freedman RS, Kudelka AP, et al. Retrospective review: re-treatment of patients with ovarian cancer with carboplatin after platinum resistance. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:209–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.15205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavanagh J, Tresukosol D, Edwards C, et al. Carboplatin reinduction after taxane in patients with platinum-refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1584–1588. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pignata S, Ferrandina G, Scarfone G, et al. Extending the platinum-free interval with a non-platinum therapy in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Results from the SOCRATES Retrospective Study. Oncology. 2006;71:320–326. doi: 10.1159/000108592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monk BJ, Coleman RL. Changing the paradigm in the treatment of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: from platinum doublets to nonplatinum doublets and adding antiangiogenesis compounds. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(Suppl 2):S63–S67. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181c104fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfisterer J, Ledermann JA. Management of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:S12–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colombo N, Gore M. Treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer relapsing 6-12 months post platinum-based chemotherapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;64:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaye SB, Colombo N, Monk BJ, et al. Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in relapsed ovarian cancer delays third-line chemotherapy and prolongs the platinum-free interval. Ann Oncol. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq353. 2010; doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pujade-Lauraine E, Paraiso D, Cure H, et al. Predicting the effectiveness of chemotherapy (Cx) in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer (ROC): a GINECO study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21 Abstract 829. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sessa C, Perotti A, Noberasco C, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of trabectedin and doxorubicin in advanced soft tissue sarcoma and breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1153–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blay JY, von Mehren M, Samuels BL, et al. Phase I combination study of trabectedin and doxorubicin in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6656–6662. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, et al. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2099–2106. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13718-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfisterer J, Plante M, Vergote I, et al. Gemcitabine plus carboplatin compared with carboplatin in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: an intergroup trial of the AGO-OVAR, the NCIC CTG, and the EORTC GCG. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4699–4707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pujade-Lauraine E, Mahner S, Kaern J, et al. A randomized, phase III study of carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus carboplatin and paclitaxel in relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (OC): cALYPSO study of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 Abstract LBA5509. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasey P, Largillier R, Gropp M, et al. 18LBA. A GCIG randomized phase III study of carboplatin (C) & pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) (C-D) vs carboplatin (C) & paclitaxel (P) (C-P): cALYPSO results in partially platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (OC) patients. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2009;7:11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gadducci A, Tana R, Teti G, et al. Analysis of the pattern of hypersensitivity reactions in patients receiving carboplatin retreatment for recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:615–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pignata S, De Placido S, Biamonte R, et al. Residual neurotoxicity in ovarian cancer patients in clinical remission after first-line chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel: the Multicenter Italian Trial in Ovarian cancer (MITO-4) retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]